minute particular

ON THE FRONTISPIECE OF The Four Zoas

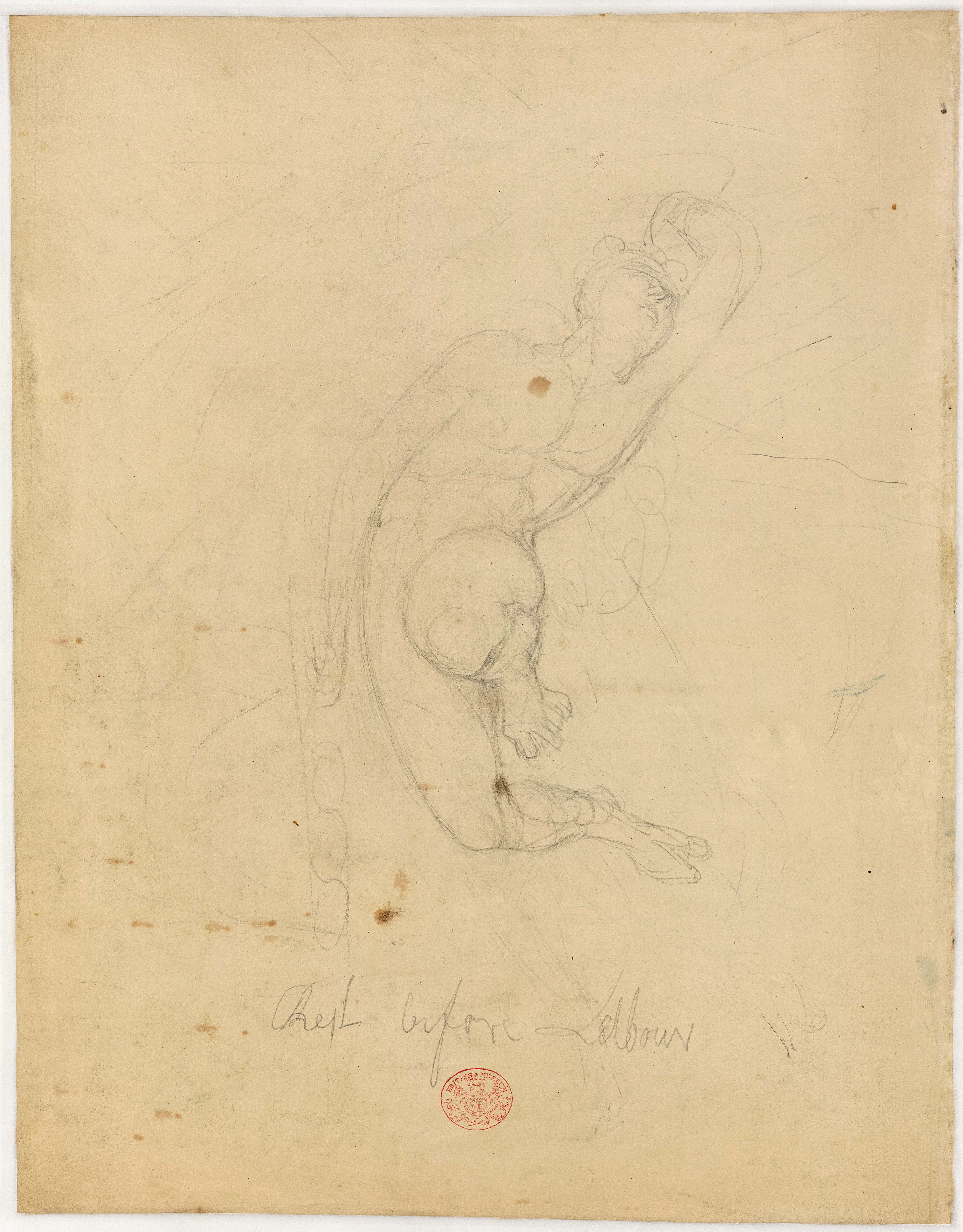

The frontispiece to The Four Zoas, a male figure sketched above the words “Rest before Labour” on ms. page 2, is as problematic as the poem itself.*↤ * I am grateful for a research grant from Ben Gurion University enabling me to study the illustrations in The Four Zoas manuscript. While Geoffrey Keynes, W. H. Stevenson, and G. E. Bentley, Jr., all describe the figure as recumbent, Bentley notes that it may alternatively be seen as soaring upward.1↤ 1 See Geoffrey Keynes, ed., Blake: Complete Writings with variant readings (London: Oxford University Press, 1969), p. 897 (hereafter K); W. H. Stevenson, ed., The Poems of William Blake (London: Longman’s, 1971), p. 292; G. E. Bentley, Jr., William Blake: Vala or The Four Zoas : A Facsimile of the Manuscript, A Transcript of the Poem, and a Study of its Growth and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963), p.2. Recently, John Grant, assuming that his predecessors based their description on the manuscript held sideways, asserts that when it is held upright, as the “inscription and the binding indicate” that it should be, “what one sees is that the man is rising, no doubt to or in his ‘labour,’ after his ‘rest.’”2↤ 2 “Visions in Vala,” in Stuart Curran and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr., eds., Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on The Four Zoas, Milton & Jerusalem (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1973), p. 146n.

But even when the manuscript is held upright, the figure remains ambiguous. That ambiguity is due, in part, to the unfinished state of the drawing and the absence of a background for reference, but it is also due to complexities inherent in his posture. Those complexities, I believe, are worthy of critical attention.

One point needs to be made at the outset. Whether Blake’s figure is reclining, or rising, or both, he certainly is not resting. He veers in several directions at once and is engaged in at least three simultaneous actions. His upper and lower torsos are contradictions of one another. As a result, his stance as a whole suggests not rest, but inner conflict and physical tension.

From the waist up, the figure bends sharply to the left in a manner reminiscent of Michael’s posture in “Michael Binding Satan.” He pillows his head in his extended left arm and, unless Blake intended him to be markedly exophthalmic, his eyes are closed. He thus appears to be sleeping. But if the upper torso suggests sleep, the lower torso suggests movement. From knee to foot the right leg suggests a soaring movement by veering leftward, literally echoing the upper torso yet, by its movement, contradicting it. It is also contrasted to the left leg which, indeed, is like a Zoa seeking separation from his fellows and attempting to exist independently of them. In an anatomically impossible position, the left leg is drastically foreshortened, with toes splayed as if the foot is pushing against a counterforce in order to heave itself upward.

The tension inherent first in the contrast between the upper and lower torsos and, second, in the effort needed to rise, is intensified by the begin page 127 | ↑ back to top presence of the chain. The chain dangles from his right hand, falling straight down in a manner reminiscent of the chain in Urizen 21. It serves as a counterforce against his soaring. Lightly sketched loops on the figure’s left, below his shoulder, make feasible the hypothesis that the chain continues from his right hand to the back of his body and is grasped in his left hand, from which it falls downward again. The effect of his posture as a whole is reminiscent of Bo Lindberg’s remark on plate 17 of the Job series: “ . . . you cannot twist a model to assume the position of Job’s friends,” Lindberg comments, “without killing him.”3↤ 3 Bo Lindberg, William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job (ACTA, Academiae Aboensis, series A: Humaniora, vol. 46, Abo: Abo Akademi, 1973), p. 119.

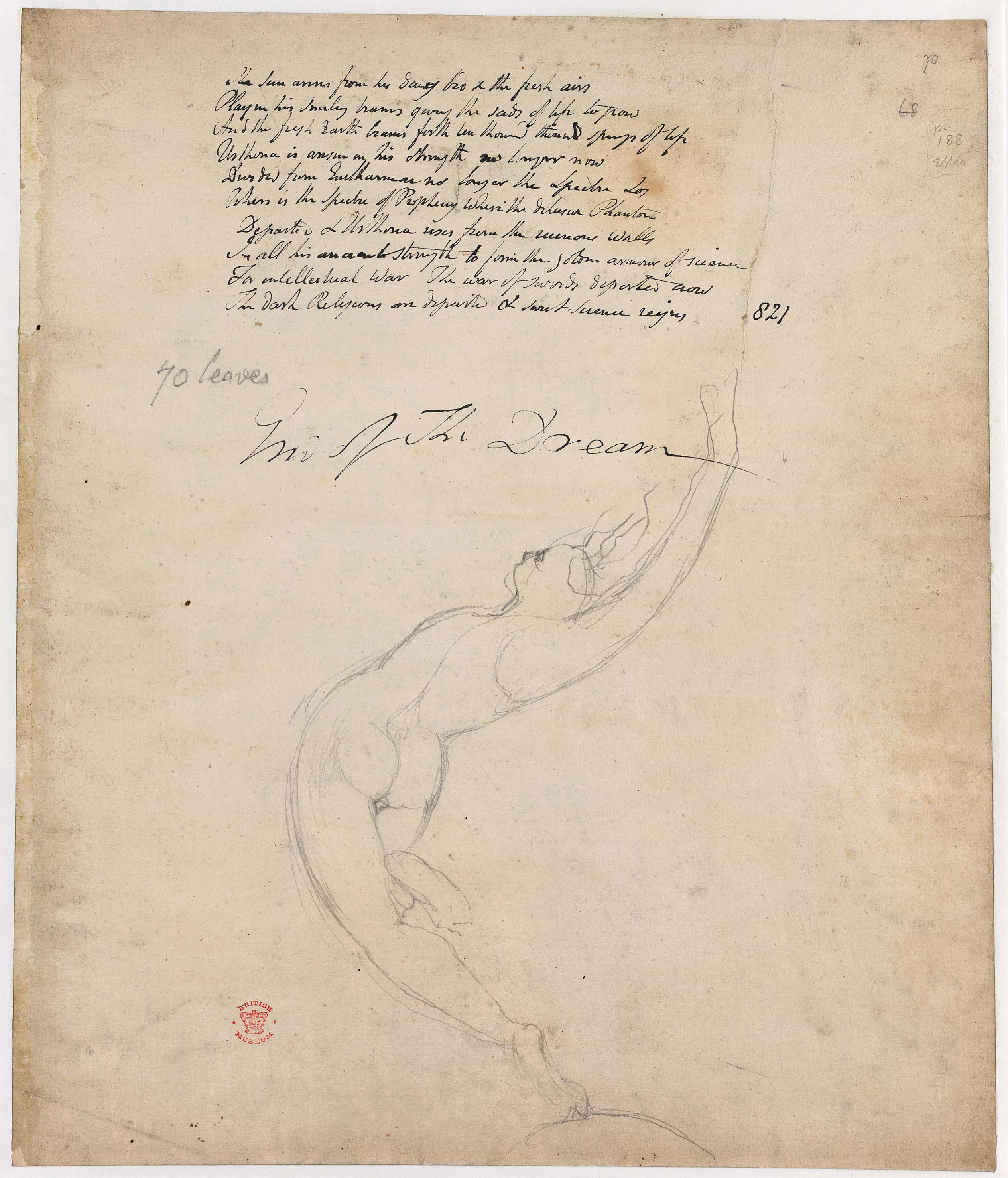

A body tense with exertion, certainly not resting yet sleeping and rising at once; the frontispiece to a work that locates itself on no objectively definable landscape and embodies the metamorphoses, displacements, and incongruities of dreams:4↤ 4 See Mary Lynn Johnson and Brian Wilkie, “On Reading The Four Zoas,” Curran and Wittreich, p. 205. it is surprising that viewers of the drawing have not recognized the figure as a dreamer and his ambiguous position as emblematic of the dream world. The drawing shows a dreamer rising as he dreams or perhaps even dreaming that he rises. Neither resting nor laboring, he embodies the state of “rest-before-labor,” the period of engagement with the psyche preluding the creation of a work of art. “What is Above is Within,” writes Blake (J 71:6, K 709): in rising, the figure is engaging himself with the images of the inner world which the poem will explore, including the “Torments of Love & Jealousy” suggested both by the chain and by the tensions inherent in his pose. On the final page of the manuscript, a female figure faces inward in a position at once reversing and echoing his; his counter-image, she is, appropriately, drawn under the words “End of the Dream.”5↤ 5 Grant identifies this figure as Enitharmon; see “Visions in Vala,” pp. 200-02.