REVIEWS

Joan Evans. A History of The Society of Antiquaries. Oxford: Society of Antiquaries, 1956. Published rebound, London: Thames & Hudson, 1977. Pp. xv + 487. 44 black-and-white plates.

“The[e] British Antiquities are now in the Artist’s hands” wrote Blake in A Descriptive Catalogue. This rebound issue of Joan Evans’s book, distributed by Thames & Hudson, and dealing with the Society’s history from its Renaissance precursors up to the early 1950’s, provides a timely opportunity for examining the intellectual context of Blake’s “visionary contemplations” concerning his own country.

Professor England has shown us how Samuel Foote’s parody of an Antiquaries meeting in The Nabob led the way to Etruscan Column’s lecture on “virtuous cats” in “An Island in the Moon.” Reading through the eighteenth-century part of this history one can see how nearly Foote held the mirror up to life. This production of the summer of 1772 must have virtually coincided with the beginning of Blake’s apprenticeship to James Basire, who had been the Society’s engraver since March 1759. Foote’s joke about Antiquaries and cats had been sparked off by a paper read by Samuel Pegge in December 1771 in which he conjectured that Dick Whittington’s “cat” had been the name of a type of ship. The ridicule prompted by The Nabob brought Horace Walpole’s resignation from the Society in 1773 but he had earlier confided his intention in a letter to William Cole written on 28 July 1772, only a few days before Blake’s exchange of indentures with Basire. Despite nineteen years of membership, Walpole’s involvement with the Society had been indifferent and recently embittered by criticism, so that this episode of “their council on Whittington and his cat, and the ridicule that Foote has thrown on them” (to Cole) provided a convenient but honorable occasion for departure.

The Basire family held their position well into the nineteenth century, and Joan Evans has made the forgiveable error of attributing William as the apprentice of James Basire the Younger who was elected a Fellow in 1823. Fortunately for Blake’s training, both master and apprentice had only the very highest standards to seek to emulate since, until his death, almost all previous engraving for the Society had been under the management and general surveillance of George Vertue. Vertue had not only been one of the Society’s founder members, but both benevolent and indefatigably active on its behalf for nearly half a century, and it was largely through his influence that the early parts of Vestuta Monumenta contained as much medieval material as they did. It was for this irregularly issued record of the Society’s activities and interests that Blake’s Westminster Abbey sketches were intended, probably following the immediate initiative of Richard Gough, who had become their enthusiastic Director the year before Blake’s entry into apprenticeship.

In his Topographical Antiquities (1768), Gough had bemoaned the lack of an antiquarian periodical begin page 288 | ↑ back to top miscellany, and during the period of Blake’s apprenticeship he put much energy into insuring the continued publication of the Society’s Archaeologia, which had begun in 1770 in order to fulfill this role. Such were Gough’s efforts in this direction that Blake’s Westminster Abbey sketches remained unpublished until 1780, but the Archaeologia, while adding a new dimension to the Society’s pursuits, radically increased the amount of engraving undertaken by Basire for the Society. During Blake’s apprenticeship, issues were published in 1773, 1775, 1777 and 1779. Most of the papers are illustrated with engravings signed by Basire, and it is a source of harmless speculation to wonder how many of them Blake had a hand in.

After his resignation Horace Walpole greeted most of the Society’s enthusiasms with amused incredulity, and there were certainly enough Archaeologia papers on such topics as cockfighting, horseshoes and buried bird bones to validate his reactions. Their interests were not narrowly in archaeological “hardware,” however, and a similar impulse to that which prompted the publication of papers on the origin of the word “Romance” and on “The Wisdom of the Ancient Egyptians” must have led the President, Jeremiah Milles, to sponsor the second edition of Chatterton’s Rowley poems in 1782 despite the cordially tepid response from the rest of the Society, who appear to have sensed the presence of forgery.

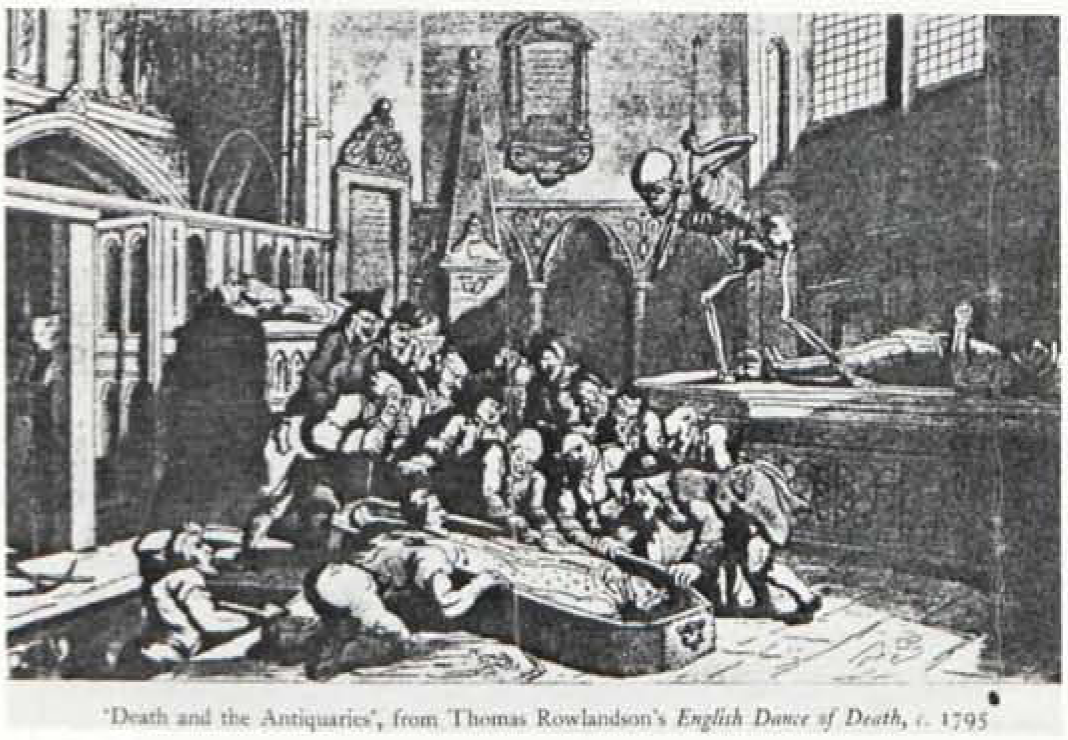

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that at this period the Society was intellectually second-rate: certainly their ranks in the second half of the century can muster no mind approaching that of William Stukeley, whose varied researches had been without parallel during the Society’s early years. Inevitably, this “antique” company of aged and conscious exclusiveness became the fair and easy victim of caricaturists from both within, such as Francis Grose, and without, such as Thomas Rowlandson. Joan Evans reproduces an interesting Rowlandson cartoon dating from c. 1795 which appears to be based on the opening of the tomb of Edward I in 1772, when Blake was probably present. Entitled “Death and the Antiquaries,” a group of antiquaries gather round an opened royal tomb, one stealing a ring from the corpse, while a skeletal Death stands outraged above. This episode was remarkable in the Society’s history because it was just about the first time they had been taken seriously enough to be allowed to interfere with a relic of national importance. The late date of Rowlandson’s plate is silent testimony enough to the uneventful obscurity to which they subsequently returned.

Although such figures in Blake’s world as Benjamin Heath Malkin and Henry Crabb Robinson found admittance to the Society at some point in their lives, the Antiquaries and their pursuits had little effect on Blake’s imagination or intellectual development. To return to his remarks in A Descriptive Catalogue, it is clear that the “British Antiquities” have already become transformed into a part of the Blake Pantheon. Blake recognized antiquity as witness to the loss of imagination and the ascendancy of memory. The sublime truth represented diagramatically in the well-known illustration of the Mundane Shell and Universes of the Four Zoas in Milton became distorted and petrified into the serpent temples of Britain. Milton’s journey from Eternity, seen in Time by Milton’s vision of Satan’s fall through the Serpentarius constellation in Ophiuchus[e] (Paradise Lost Bk. II), was distorted by the Druids into the serpent and mundane shell configuration of the serpent temples. The transfiguring re-emergence from the mundane shell, which Blake characterizes as being without dimension, became further distorted by Druidic vision into the other half of the serpent ascending out of the circle of stones in unconscious repetition of the original fall. This portrayal of the cosmological through the antique probably had its beginnings in the eighteenth century’s association of stone circles with sun worship, but the development is so extensive as to leave these theories far behind. In similar fashion, Blake’s reference to the “pavement of Watling-street” in A Descriptive Catalogue comprehends not only the ancient Roman road but the traditional English (and Chaucerian) name for the Milky Way.

Unfortunately, the antiquarian writers Blake most obviously seems to have admired, such as Jacob Bryant and Edward Davies, figured little if at all in the Society’s affairs and neither finds acknowledgement in Joan Evans’s book. The congenial literary and mythological emphasis of these writers was declining in importance as more scientific methods of inquiry began to assert their worth (to the Society’s benefit, it has to be said). Outside the Society, isolated enthusiasts continued their researches relatively untroubled by the consensus of informed development, and it was from these quarters that some of the most imaginative studies stemmed. In the final years of the eighteenth century, the antiquarian writer who most obviously exemplified the virtues Blake admired was Thomas Maurice, whose Indian Antiquities ranges over the cultures of the major Mediterranean, Northern and Eastern civilizations before returning to an extended account of Stonehenge and ancient Britain during the course of proving his thesis that all nations have spontaneously recognized a divine trinity. For the student of the backgrounds of Romanticism in comparative mythology and antiquity, Maurice’s work provides a clear and well-documented guide to the state of research as it existed in these fields and may be used in conjunction with the broad outlines offered by Joan Evans, but the Blakeophile will inevitably need to consult A History of The Society of Antiquaries for knowledge of the Society’s interests and personalities during the period of his apprenticeship.