REVIEWS

Joseph Burke. English Art 1714-1800. Oxford History of English Art, vol. IX. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977. xxxii + 425 pp., 120 plates. £ 12.50.

The eighteenth century in artistic terms did not stop in 1800. Crucial ideas were still developing and flourishing well into the nineteenth century. The period about 1800 was one of artistic excitement, as well as a time of literary and political upheavals. Neoclassicism, the main movement or style, was only in the middle of its second phase about 1800; the final, third stage had yet to emerge. This fact was recognized by the organizers of the “Age of Neoclassicism” exhibition held in London in 1972; they gave themselves a brief covering the period up to 1840. The other main umbrella often used to cover the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries is obviously that of Romanticism. That interesting show in Detroit and Philadelphia in 1968, “Romantic Art in Britain,” was devoted to the century between 1760 and 1860. Although these dates were arguably a bit too far apart, especially at the latter end, it was a fault in the right direction.

Yet for chronological convenience the editors of the Oxford History of English Art and the Pelican History of Art have chosen either 1800 or 1790 as terminal dates when commissioning eighteenth-century studies. At least in the Pelican series the British sculpture and architecture volumes by Margaret Whinney and John Summerson go as far as 1830, but the painting survey by Ellis Waterhouse stops in begin page 213 | ↑ back to top 1790. For a continuation into the nineteenth century in the Pelican series we await Michael Kitson’s volume. In the Oxford series we have T. S. R. Boase’s volume, which covers the first seventy years after 1800. In this instance a terminal date of 1870 makes sense, but that is another story not for discussion here.

Burke seems to hint at the difficulty of his concluding date in the final paragraph of his book. Discussing Wordsworth, in a chapter entitled “The Transition to Romanticism,” Burke writes that the poet, “who disliked the picturesque and described it in The Prelude as ‘ . . . a strong infection of the age. . . . / Bent overmuch on superficial things’, has in these two passages identified the dividing line between the Rule of Taste and the liberty of nature, crossed by artists as well as poets well before the close of the century in which he spent the first thirty years of his life” (my italics).

Not only do the dates of 1790 or 1800 distort what was actually happening in the art world, it also cuts through the careers of major artists whose lives happen to span the end and the beginning of the centuries. This is of course inevitable with any date that is selected at any period. But in the case of these standard histories there are some unfortunately truncated artists whose two halves never seem to meet each other, apparently leading separate lives, and reminding one of the two halves of the Visconte dimezzato in Italo Calvino’s fairy tale.

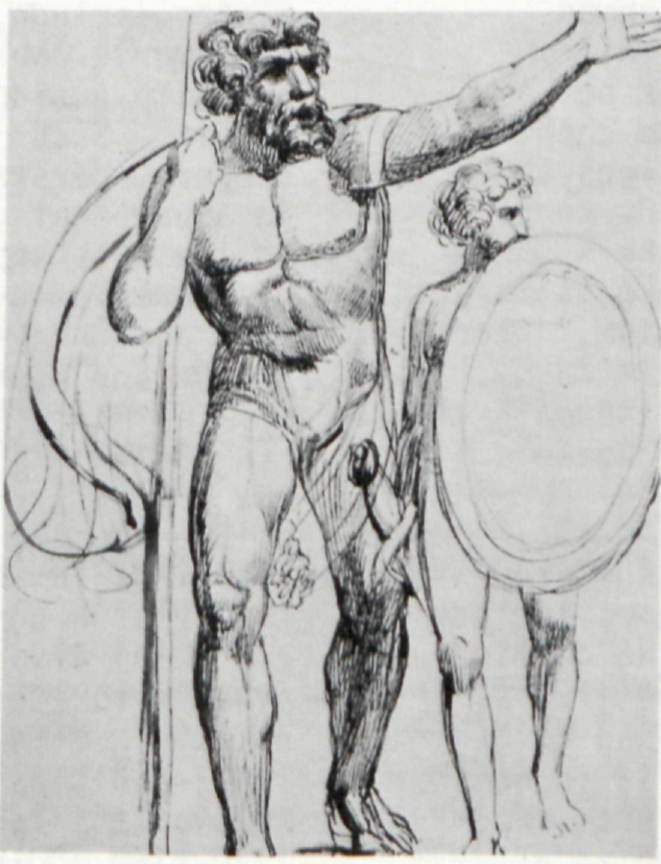

In the context of this periodical, it will be appropriate to start by looking at the results of editorial policy in the Oxford series on the career of William Blake. In Burke’s volume he is mentioned on four occasions. In an excellent chapter devoted to “The Royal Academy and the Great Style” Blake appears, along with Turner, as one of the painters whose imaginations were “haunted all their lives by themes of istoria.” Later in the same chapter, whilst discussing James Barry’s paintings at the Society of Arts, Burke says that the Irishman lacked the “mystic fervour” of Blake, a fair comparison since Barry could on occasions be singularly earthbound. Still in the same chapter, whilst mentioning single-handed undertakings to illustrate the works of famous authors, Burke mentions Fuseli’s Milton Gallery and Blake’s Dante project. The only other citation of Blake is in a chapter on “The Expansion of Neo-Classicism,” where Burke quotes from the 1809 Descriptive Catalogue. Each of the references is apposite, but the main discussion of Blake does not occur until Boase’s volume.

Some of the other artists who have suffered similarly by being torn between two volumes include John Flaxman. His early period, embracing commissions for Wedgwood and major works in the 1790’s, features in Burke, but later works have had to be omitted and appear in Boase. As a result, in neither volume is Flaxman’s overall development discussed properly. Fuseli hardly comes into Burke at all. Sir Thomas Lawrence and Thomas Rowlandson are omitted. Sir Henry Raeburn, a fine portraitist who is much underrated in the general literature, appears on only one page in Burke, and is also scantily treated by Boase, and is therefore virtually omitted by both authors. Of the principal artists at the turn of the century one of the few to receive anything like adequate coverage is Benjamin West. But like Flaxman his oeuvre as a whole is unsatisfactorily treated.

Editorial decisions over dates are one matter, the actual content of Joseph Burke’s volume is quite another. It is a brilliantly skillful compression within four hundred pages of a great deal of material and especially valuable since it discusses all the arts, including gardening and the decorative arts, within the covers of one book—a virtue of editorial policy, since this is a characteristic of all the Oxford History of English Art series. Too often in art historical literature, painting, sculpture and architecture are discussed in isolation from each other, and the decorative arts are usually squeezed out or given a mere nod. Art historians, with a few exceptions, have been such snobs over the decorative arts in the post-medieval period, relegating research on them—quite wrongly—to a lower order of intellectual activity. The barrier between the so-called “fine” arts and the rest is only a recent invention, for which Michelangelo is partially to blame. It is a barrier which did not exist in the eighteenth century, since artists like Robert Adam and Flaxman were not alone in designing in several fields. Across the Channel, the decorative arts were of crucial importance in contemporary France, and an integral part of the artistic creativity of the time, yet they are omitted from the Pelican History of Art volume by Wend Graf Kalnein and Michael Levy, thus diminishing its usefulness.

It was particularly encouraging therefore to open Burke’s volume and find amongst the plates a double-page spread showing a Rococo staircase in a country-house in Devon opposite a Rococo design for a table and a silver wine cooler. The plates in general are in fact refreshingly unhackneyed. Other plates include a Roubiliac monument opposite a Paul de Lamerie ewer; and a Robert Adam staircase opposite a sideboard and other furnishings designed by him. Such juxtapositions make a fuller and deeper understanding of the whole period possible, in a way that cannot be achieved in volumes devoted to the arts separately. Some styles cannot be discussed adequately without taking all the arts into account; this is especially the case with the Rococo and with Neoclassicism.

Burke has some particularly good passages on the decorative arts. His discussion of the “Impact of the Rococo” in his fifth chapter[e] is a model of its kind, in which the essential interweaving of all the arts in the eighteenth century is very apparent, embracing also literature and music. The author had given a foretaste of his ideas in an interesting article published in Eighteenth-Century Studies in 1969, entitled “Hogarth, Handel and Roubiliac: a note on the interrelationship of the arts in England 1730-1760.” In the same spirit Jean Hagstrum had written his important Sister Arts (Chicago Univ. Press, 1958) and more recently Morris Brownell has begin page 214 | ↑ back to top published his Alexander Pope and the Arts of Georgian England (Oxford Univ. Press, 1978). Ronald Paulson has produced some particularly stimulating articles on art written from the vantage point of an historian of English literature, often giving a refreshing new look at eighteenth-century Britain. Some of his articles on art have been usefully gathered together under the title of Emblem and Expression (Harvard Univ. Press, 1975). Within this growing awareness of interrelationships, Burke firmly places the silver, ceramics and furnishings of the period. The more boundaries that are broken down between the arts, and in many instances between disciplines themselves, the better. For a masterly new look at all the arts in eighteenth-century Britain, Burke’s book is to be greatly welcomed and much valued.

As Britain has so often since the medieval period been a follower rather than a leader in the arts within a European context, the eighteenth century is an especially creative period. British contributions were of major importance in the areas of landscape-gardening and of Neoclassicism. Although one recent scholar would like to take Britain’s lead away from her by saying that the “picturesque” garden was invented in France (heretical and unconvincing view!), any study of British art in the eighteenth century must have a great deal to say on the subject of both landscape gardening as well as landscape painting. Such a discussion must be interdisciplinary, and Paulson in his collected essays almost inevitably has a piece on “The Poetic Garden,” starting with a walk at Castle Howard. Burke, on the other hand, starts his discussion with theory, with Shaftesbury and Pliny. Within less than thirty pages, Burke manages to squeeze in all the essentials, in an area of research that is now at last being developed, having lain largely dormant since Christopher Hussey’s magnum opus.

As one would expect in a history of this kind, Burke discusses all the main artists and a surprisingly large number of minor ones as well. He is able, because he is looking at all the arts, to discuss Hogarth and Roubiliac in the same chapter; he naturally gives prominence to Reynolds; and he has much to say of interest about the development of architecture from the Palladians onwards. The only shift in the balance of priorities that I would like to have seen was more space devoted to Allan Ramsay, whose portaits are just as fine as—and occasionally finer than—those of either Reynolds or Gainsborough. Indeed in eighteenth-century studies in general, Gainsborough is in danger of being overrated. It is unfortunate that Ramsay is only allocated one plate, and that of the unusually dull portrait of the third Duke of Argyll.

Other reviewers have already pointed out that the long delay in the publication of the manuscript, finished in 1973, with parts completed even earlier, has meant that recent books and articles—although in some instances mentioned by the author—were not available for the main writing. The delay has also meant that minor details have not been updated, of which only two instances will be cited. We now know more about the mysterious Mr. Lightfoot responsible for the delightful Chinoiserie decorations in Claydon House, including even his Christian name. Amongst the plates, it would have been better to have included a more recent photograph of the Library at Kenwood. The later bookcases on either side of the fireplace have now been removed, and replaced by a very successful reconstruction of Adam’s original mirrors, which has given the room an additional vitality in their reflecting light. But all such outdated information can easily be remedied in a second edition.

Overall, the author has written an immensely useful and indispensible working tool for anyone studying the eighteenth century. As Burke’s volume is conceived quite differently from the rival Pelican series, he has provided the kind of book for which there has long been a need.