review

Richard D. Altick. The Shows of London. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978. 553 pp., 181 pls. $35.

The reader is warned that this will not be a comprehensive review of Professor Altick’s fascinating history of London exhibitions from 1600 through 1862. Instead, it seems appropriate for us to take a Blake’s-eye view of the proceedings; to ask what The Shows of London has to tell us about the life of the great city in which Blake lived and moved. Although the results are necessarily speculative—Blake’s name is mentioned only once in the book (p. 408)—they are, I think, worthwhile. Blake was, as we have come to realize more and more, a man very much in his time; and Altick’s richly informative history gives us, both in its text and in its wealth of illustration, much to imagine about what Blake could have seen and heard. —And, after all, “What is now proved was once, only imagin’d.”

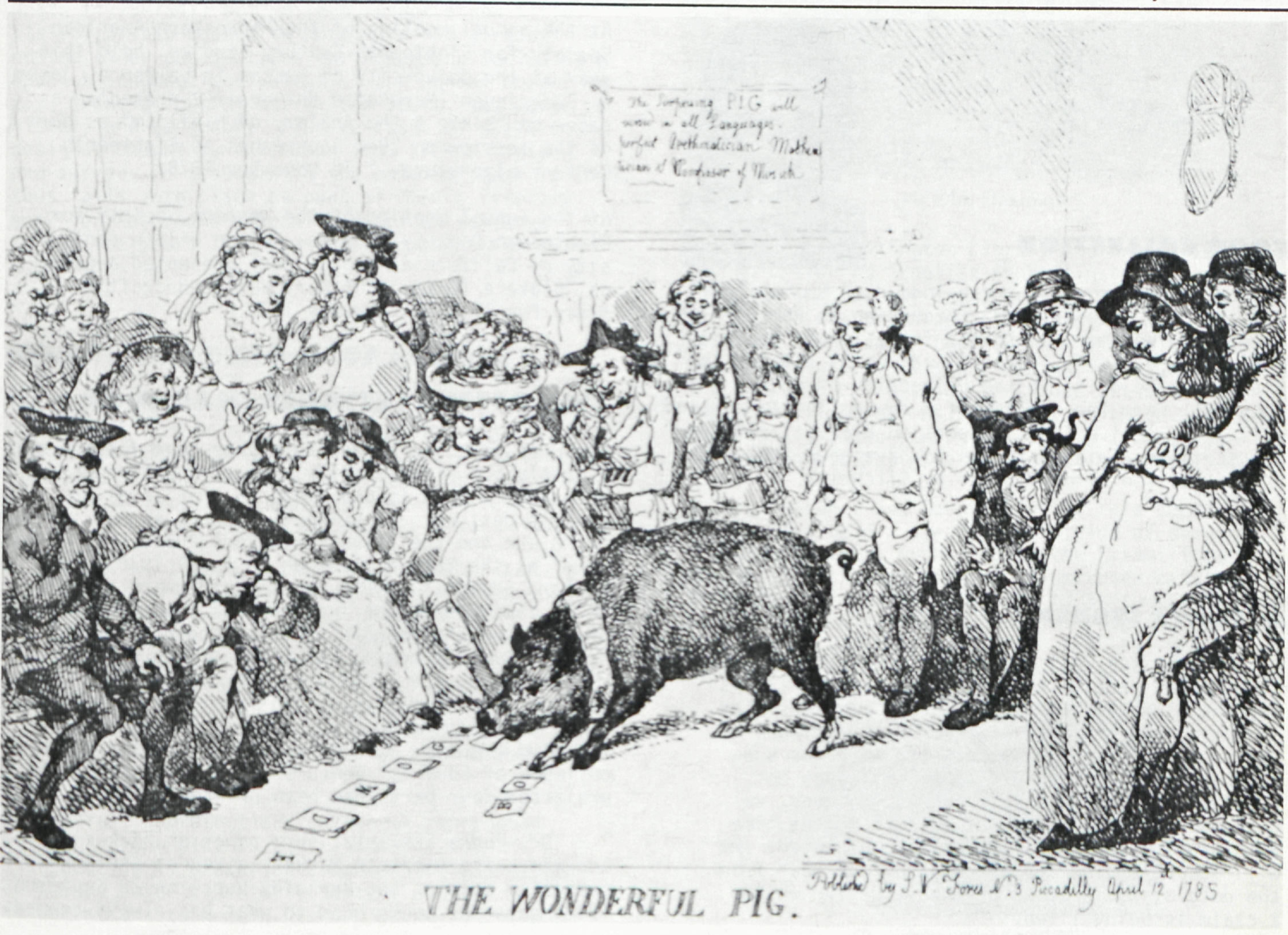

Could Blake have seen a real Tyger,1↤ 1 On this subject, see also John Buck, “Miss Groggery,” Blake Newsletter, 2 (1968), 40. whatever the explanation of the enigmatic nature of his design? Perhaps the likeliest place was the menagerie at Exeter Exchange, where George Stubbs bought a dead tiger for his anatomical investigations (p. 39). That was presumably in the late 1770’s, though Altick does not give a date; there were tigers at the Exeter Exchange again in 1797, and elephants as well. As for the Learned Pig of Blake’s epigram,2↤ 2 See “Give pensions to the Learned Pig” in The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970), p. 506. This edition is hereafter cited as E. For later learned pigs, see Altick, p. 307. the most celebrated of that breed performed in London in 1785 (pp. 40-42); it was advertized as “well versed in all Languages, perfect Arethmatician & Composer of Musick” and was the subject of a caricature print by Rowlandson (The Wonderful Pig, fig. 46). For hares playing the tabor Altick refers us elsewhere3↤ 3 To J. Holden Macmichael, The Story of Charing Cross and Its Immediate Neighbourhood (London, 1906), p. 66. —but play it they did.

Among human performers of possible interest to Blake, we find Dr. Katterfelto, now a leading candidate for the prototype of Inflammable Gass the Windfinder.4↤ 4 See David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, rev. ed. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 94n. “According to his flamboyant publicity,” writes Altick, “his ‘lectures’ and ‘experiments’ . . . drew on ‘mathematics, optics, magnetism, electricity, chemistry, pneumatics, hydraulics, hydrostatics,’ and such obscure realms as ‘proetics,’ ‘stynacraphy,’ and ‘caprimancy’” (p. 84). In An Island in the Moon, though, it’s Chatterton rather than the Windfinder whom Aradobo calls “clever at Fissic Follogy, Pistinology, Aridology, Arography, Transmography, Phizography, Hogamy Hatomy, & hall that . . . ” (E 444). In 1782-83 Katterfelto was entertaining audiences by projecting through his solar telescope images of the “insects” which supposedly caused influenza. He also sold a remedy, Dr Bato’s medicine, against the disease. (“I have got a bottle of air that would spread a plague,” says Inflammable Gass—E 442). Katterfelto also used black cats for electrical demonstrations, in the course of which they gave off sparks. By 1783, however, Katterfelto had exhausted his popularity and offered for sale his “philosophical and mathematical apparatus”—perhaps the “puppets” with which Inflammable Gass proposes to “shew you a louse [climing] or a flea or a butterfly or a cock chafer the blade bone of a tittle back . . . ” (E 452). In an anonymous caricature of 1783 (fig. 16), Katterfelto prepares to joust with another quack, Dr. Graham, both mounted on phallic instruments. Katterfelto threatens Graham with “Fire from mine findger and Feavers on my Tumb”; in An Island “Inflammable Gass turnd short round & threw down the table & Glasses & Pictures, & broke the bottles of wind & let out the Pestilence.” (E 453)

Was Blake interested in spectacles such as the Phantasmagoria and the Eidophusikon? The Phantasmagoria and its successors (pp. 217-220) depended for their effect on magic lantern projections in a dark room, and this may well have been too begin page 272 | ↑ back to top mechanical for Blake’s taste. The Eidophysikon was another matter, involving brilliant artifice rather than thrilling illusion. Performances usually culminated with the Pandemonium scene of Paradise Lost, a subject to which Loutherbourg brought the same inventiveness that he displayed as Garrick’s scene designer. Drawing upon the supposed eyewitness account of William Henry Pyne, Altick describes the effect as follows:

‘Here, in the fore-ground of a vista, stretching an immeasurable length between mountains, ignited from their bases to their lofty summits, with many-coloured flame, a chaotic mass rose in dark majesty, which gradually assumed form until it stood, the interior of a vast temple of gorgeous architecture, bright as molten brass, seemingly composed of unconsuming and unquenchable fire.’ . . . In this palace of the devils, serpents were entwined around the Doric pillars, and as the fires rose the intense red gave way to a transparent white, ‘expressing thereby the effect of fire upon metal’ . . .Although Reynolds and Gainsborough were among the early admirers of the Eidophusikon, the five shilling admission price probably put the show beyond Blake’s means in 1781; there were, however, more popularly priced productions at Exeter Change in 1786 and at Spring Gardens in 1793. Loutherbourg’s device was in its way a work of composite art, and of the various pre-cinematic inventions discussed by Altick, the Eidophusikon is by far the most interesting.

The Shows of London is also generous in its descriptions of places in which exhibitions took place or which were themselves exhibitions. Among these are Vauxhall, Ranelagh, the Temple of Flora, and Apollo Gardens, all alluded to in Blake’s works. At the time when Miss Gittipin enviously said “There they go in Post chaises & Stages to Vauxhall & Ranelagh” (E 447), these were indeed places of resort with certain pretensions—Vauxhall even had a picture gallery of works on Shakespearean subjects. But by the early nineteenth century, “Vauxhall’s developing reputation for occasional riotousness and licentiousness (it became something of a summer retreat for a class of women then known by the erudite euphemism of ‘Paphians’) eventually sped its decline” (p. 320). Ranelagh, celebrated for its immense rotunda and for a fireworks show which depicted the Cyclops forging Mars’s armor in the cave of Vulcan, closed in 1803. Fittingly it is one of the places from which Hand rises up against Los in Jerusalem 8:1-2 (E 149). As for the Temple of Flora and the Apollo Gardens, Altick’s information usefully supplements that previously given by David V. Erdman.5↤ 5 Ibid., pp. 288-90. The Temple of Flora or British Elysium was erected in 1786 in St. George’s Fields on the Surrey side of Westminster Bridge. “ . . . This resort boasted a summer garden, a winter garden, an orange grove, a hothouse with a statue of Pomona, a Chinese pagoda, goldfish ponds, and a grotto complete with the indispensable hermit” (p. 97). Across Oakley Street was the Apollo Gardens, where, in addition to horticultural displays, transparencies of George III and his family (including one showing their first meeting after the King’s recovery from an attack of madness) could be seen. But these places too declined and closed as “An originally respectable, if not fashionable clientele gave way to low-life characters whose riotous behavior got the managements in trouble with the neighbors and the magistrates.” Thus, as Erdman points out, we have Blake’s reference in Milton 25:48-49 to “Jerusalems Inner Court, Lambeth ruin’d and given / To the detestable Gods of Priam, to Apollo. . . .”

Many buildings are illustrated and described in The Shows of London, and Blake, as a walker in London’s opening streets, must have been familiar with at least the exteriors of, among others, the Pantheon, the Panorama, and the Egyptian Hall. Built at the corner of Oxford and Poland Streets in 1772, the Pantheon occupied the site until it burned down in 1792; in 1784 Lunardi’s balloon was exhibited there (fig. 17). The circular Panorama, where an astonishing 360 degree view of London was displayed (figs. 29, 30), opened in Leicester Square in 1794. Perhaps most interesting of all as a building was William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall on Piccadilly near the end of Old Bond Street (fig. 69), begun in 1809 and opened in 1812. Bullock’s London Museum (as it was officially known) was designed by Peter Frederick Robinson in a style which Altick terms “Egyptian eclectic”:

It was nominally inspired by the great temple of Hat-hor at Dendera, a late Ptolemaic and Roman building which then was counted among the most impressive Egyptian monuments. . . . The central facade was crowned by a huge cornice supported by sphinxes and two colossal nude statues in Coade stone representing Isis and Osiris. (p. 236)Given Blake’s long-standing interest in the highly cultivated state of Egypt, this striking edifice must surely have interested him. In 1820 the Egyptian Hall housed Giovanni Belzoni’s sensational exhibition of the Tomb of Seti and other Egyptian antiquities, prefiguring, as Altick suggests, our own Treasures of Tutankhamen.

Only two chapters of The Shows of London are about paintings; although this probably gives the subject the relative importance it had in relation to Londoners’ other showgoing tastes, a full length history of London art exhibitions has yet to be written. Among the events described by Altick, the Orléans shows of 1793 and of 1798-99 stand out in importance. The first is characterized as “the first exhibition of Old Masters ever held in England”; consisting of Flemish, Dutch, and German paintings, it had an enormous success and attracted more than two thousand people during its last week alone. The second comprised the French and Italian paintings acquired for the Bridgewater, Carlisle, and Gower collections. It is hard to believe that Blake would not have taken the opportunity to see these treasures, and it is a pity that we do not have his response as we do Hazlitt’s: begin page 273 | ↑ back to top ↤ 6 P. 104, quoted from “The Pleasures of Painting.”

A mist passed away from my sight; the scales fell off. A new sense came upon me, a new heaven and a new earth stood before me. I saw the soul speaking in the face . . . .6Of other important art exhibitions in Blake’s time, some one-man shows stand out, giving us an idea of what Blake was trying to accomplish with inadequate material resources in 1809-10. John Singleton Copley drew 20,000 persons to see his The Death of Earl Chatham in the Great Room at Spring Gardens during six weeks of 1781; and in 1791 60,000 persons saw Copley’s The Floating Batteries At Gibraltar in a tent near Buckingham House (p. 105). A generation later, Benjamin Robert Haydon, whose aspirations in so many ways resembled Blake’s, showed Christ’s Triumphal Entry Into Jerusalem at the Egyptian Hall: over thirty thousand visitors paid a shilling a head to see the painting in 1820 (p. 243). Blake did not have the means to rent a fashionable showroom and to invite persons of quality to a private view, but we can see that in a modest way he was trying to do what Copley had done and what Haydon would do: to appeal to the public directly, without the

The Shows of London is of course much more than a compendium of information about London exhibitions. It is a study in cultural history, one which might take for its motto “By their amusements shall ye know them.” All who visit Altick’s Panorama will, like their counterparts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, find both pleasure and instruction.