article

begin page 4 | ↑ back to topBLAKE’S RESPONSE TO WOLLSTONECRAFT’S ORIGINAL STORIES

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

It appears certain that William Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793) was partly inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).1↤ 1 David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 2nd ed. (Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 243; and Mark Schorer, William Blake: The Politics of Vision (New York: Henry Holt, 1946), p. 290. In “Notes on The Visions of the Daughters of Albion,” MLQ, 9 (1948), 292-97, Henry H. Wasser argues that Visions is about Wollstonecraft and Fuseli, Blake’s friend. It likewise appears true that two of his songs of Innocence, “The Little Boy Lost” and “Found,” had their source in C. G. Salzmann’s Elements of Morality, which Wollstonecraft was translating in 1789 and which Blake did several engravings for.2↤ 2 Joseph Wicksteed, “Blake’s Songs of Innocence,” TLS, 18 February 1932, p. 112. In “The Figure in the Carpet,” Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, 12 (1978), 10-14, Robert N. Essick notes stylistic similarities between two engravings in Elements (pls. 28 and 47) and two of Balke’s illustrations for Original Stories (the frontispiece and pl. 6). That he met Wollstonecraft through his acquaintance with her novel, Original Stories, also seems likely.3↤ 3 Erdman, Blake, p. 156. For the second edition of the novel, published in 1791, he designed and engraved six plates.4↤ 4 Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1791). See Geoffrey Keynes, A Bibliography of William Blake (New York: The Grolier Club, 1921), p. 199; and Roger R. Easson and Robert N. Essick, William Blake: Book Illustrator (Normal, Ill.: American Blake Foundation, 1972), I, 9-12. All subsequent quotations from Original Stories are from the 1791 edition, indicated with page numbers in parentheses. But whether his poetry and art were influenced by Original Stories has never been clarified. The purpose of this essay is to reveal a number of relationships between Wollstonecraft’s novel and Blake’s writing, art, and ideas.

As the book’s illustrator and as the author of the Songs of Innocence (1789), Blake was likely to have read this short novel on the moral education of children. D. G. Gillham says that the poet “alludes to” or “uses” it in the Songs of Experience (1793). Referring apparently to the novel and Wollstonecraft’s other works on “education,” Stanley Gardner says that Blake knew her views “well” and that he turned them “into poetry in which we recognize our own adult anticipation, which caresses the infant inevitably toward Experience.”5↤ 5 Gillham, Blake’s Contrary States: The “Songs of Innocence and of Experience” as Dramatic Poems (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1966), p. 97; Gardner, Blake (New York: Arco Publishing, 1969), p. 124. Gillham and Gardner to not add anything further to these comments, but they are well taken, especially Gardner’s. Although he understates the force of “adult anticipation” (in both Wollstonecraft and Blake), his assertion is particularly important to our understanding of Blake’s response to Original Stories, a novel that begin page 5 | ↑ back to top seems to compare with Rousseau’s Ëmile. In Original Stories the main character, Mrs. Mason, acts as a governess for two young girls, Mary and Caroline. Like Ëmile the girls need a tutor since they are for all practical purposes orphans. Their mother has died and they have been left to the care of servants (p. vii). To teach these girls to be good, Mrs. Mason continually exposes them to their faults and to the need to behave morally in the “real world.” The thesis of this article is that, while Blake recognized the necessity of living in experience, he responded unfavorably to the novel’s emphasis on experienced vision, which divides life into false categories like good and evil and is negative, oppressive, and dehumanizing. Such vision had already been of some concern to him in a few poems in the Songs of Innocence. I suggest that his reaction to it was intensified by his familiarity with Wollstonecraft’s novel and its main character, Mrs. Mason, who, unlike Ëmile’s tutor, neither regards children as independent nor educates them to be so.6↤ 6 According to Rousseau, female independence is subservient to man’s, however. See the section entitled “Sophie ou la femme” in Ëmile (Paris: Garnier Frères, 1964), pp. 445-574. In the following paragraphs I discuss the character of the governess, showing how Blake reacted to her kinds of attitudes and concerns in (1) his own writing, (2) some of the designs for his illuminated works, and (3) the illustrations for the novel itself.

Wollstonecraft’s aim in writing Original Stories was to make up for some of the parental neglect in her society (p. v). To accomplish her aim she used her novel to impart “premature knowledge” about good and evil to the young (p. v), who, according to her personal views and those of other educators (including Rousseau), ought to receive such knowledge only gradually (p. iv). At the center of her effort is the character of Mrs. Mason, whose attitudes toward life and children and whose approach and emphasis in teaching were no doubt offensive to Blake. For Mrs. Mason life has been “very unfortunate,” as she says (p. 122). Having suffered the loss of loved ones, she cannot dispel her sense of “gloom” (p. 123). Preoccupied with her bleak view of existence (see p. 148), the governess imposes it on her charges just as the speaker in Blake’s “Infant Sorrow” imposes her dark vision on the child in her care.7↤ 7 I agree essentially with Gillham’s and Brian Wilkie’s views that the speaker in “Infant Sorrow” is an embittered adult who dwells on the sorrows of birth and life (Blake’s Contrary States, pp. 180-81; “Blake’s Innocence and Experience: An Approach,” Blake Studies, 6 [1975], 127). According to this speaker, whom I take to be the maternal figure in the illustration of the poem (illus. 1), her birth was a tragedy and so she tells her child: “My mother groand! my father wept. / Into the dangerous world I leapt. . . .”8↤ 8 The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, commentary by Harold Bloom (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1970), p. 28, 11. 1-2. The subsequent quotations from Blake’s writings are from this edition (E), indicated with page or plate and, where appropriate, line numbers in parentheses. With this attitude it is no wonder that the mother in the illumination of “Infant Sorrow” appears so solicitous, wishing like Mrs. Mason to give all the adult knowledge and help she can to the youth for whom she is responsible.

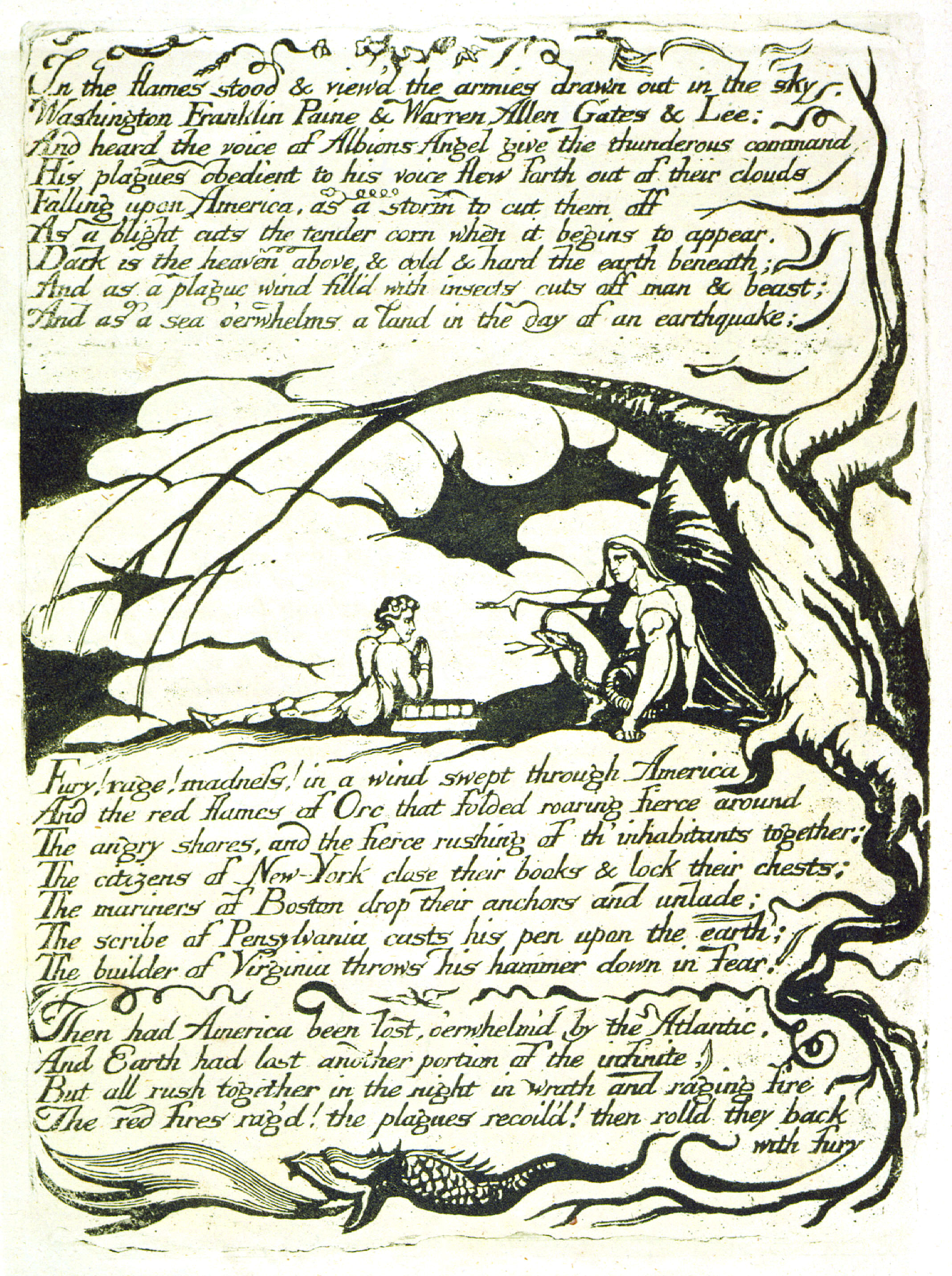

Like the governess she means well. But her view of youth (her own and presumably her child’s) is mostly negative (11. 3-4). It is a view that resembles Mrs. Mason’s. Children are ignorant, helpless, and potentially wayward—in need of guidance and control (11. 5-8, “Infant Sorrow”; pp. 103-06, Original Stories). Because Mary and Caroline are so undiscerning, the governess seldom allows them to read the Bible (p. 13)! Instead, like the gloomy instructress on plate 14 of America (illus. 2), she keeps them steadily occupied with her teaching; without her direction they will not be able to get along in society. Blake may be satirizing her excessive sort of care in another of his guardian figures—the nurse in his design for “The Fly” (illus. 3). This nurse hovers over a child “in a solicitous manner which seems stifling,” as John Grant says.9↤ 9 John E. Grant, “Interpreting ‘The Fly,’” in Blake: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Northrop Frye (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 49. See also Erdman, The Illuminated Blake (Garden City, N. Y.: Anchor Books, 1974), p. 82. Like the nurse, Mrs. Mason tries not to let her wards “out of her sight” (p. viii). She fosters their dependence on her, for despite her efforts to teach them goodness and virtue she does not trust them to remain steadfast. Thus, at the end of the novel when the girls are about to return to their father, the governess says that she fears for them (p. 175).

Children, alas, are weak, all too prone to forming “illusions” (p. 122) and being deceitful. For Blake such an opinion is an adult imposition on the young, an imposition that begins with the earliest stages of child rearing and invariably affects many a child’s view of himself. The poet

begin page 6 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The governess’s lack of trust in young people is revealed also by her disapproving eye—the kind of eye that Blake was to describe with bitter irony in “A Little Girl Lost.” Just as Mary and Caroline move toward experience and feelings of guilt under Mrs. Mason’s suspicious eye, so does Ona under her father’s “loving [actually condemning] look” (E 29, 1. 27). The governess’s “quiet steady displeasure” makes her charges feel “so little in their own eyes” that they appear visibly ashamed (p. 52). Ona appears likewise; with her father’s disfavor she looks “pale and weak” (1. 30). Mary and Caroline are also frightened by Mason’s disapproving eye (p. 53); similarly, Ona shakes “with terror” at her father’s look (1. 29).

begin page 7 | ↑ back to top

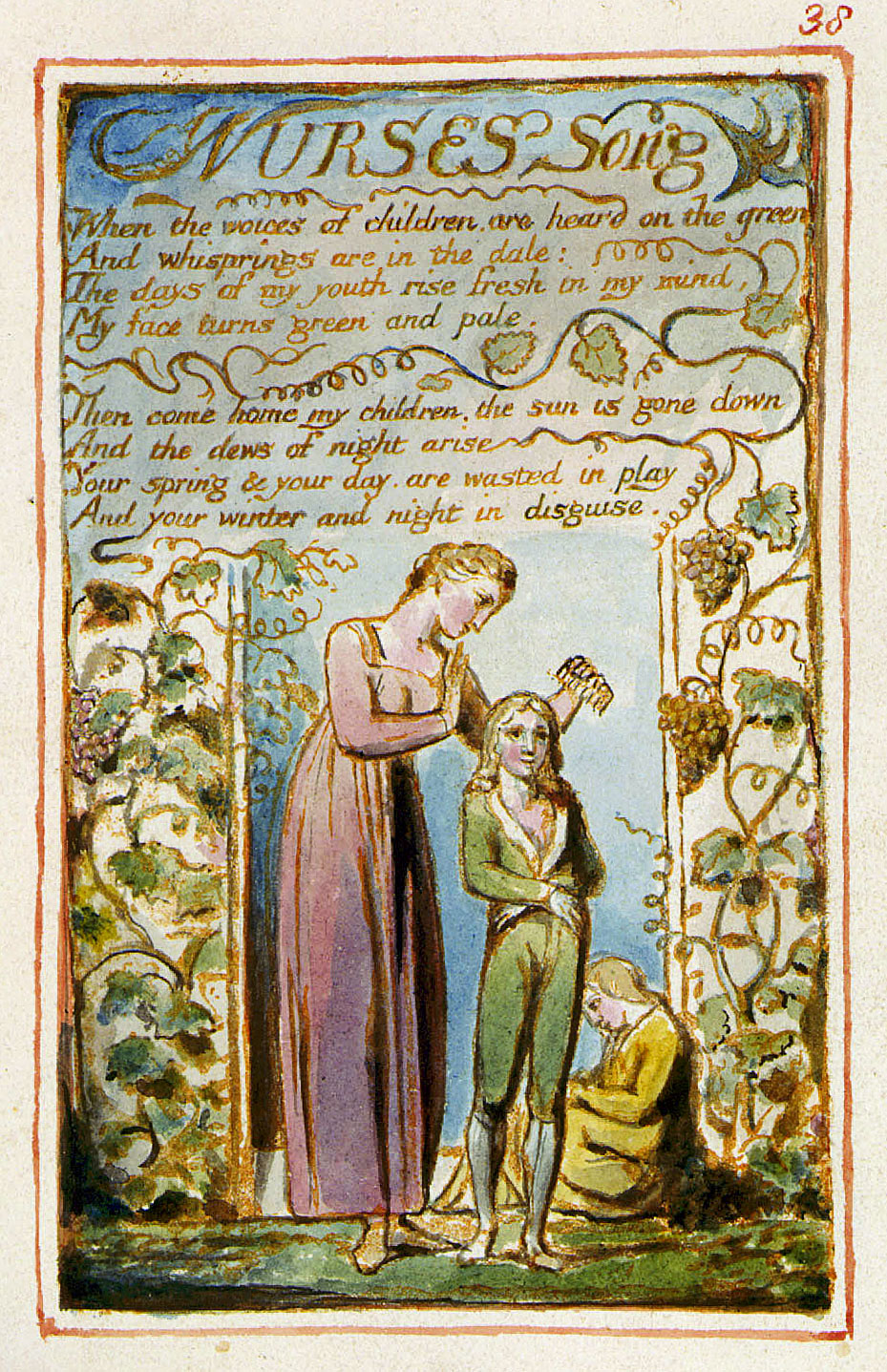

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The real significance of attitudes like those of the governess and Ona’s father did not elude Blake. As guardians committed to moral virtue these characters are, in fact, accusers of sin—the likes of which angered the poet throughout his entire career. According to his annotations to Berkeley’s Siris (c. 1820), “The Moral Virtues [and their advocates] are continual Accusers of Sin & [they] promote . . . Dominency over others” (E 653). Although Mrs. Mason uses the word “sin” only once (p. 108), she domineers over her charges, continually correcting them for offenses against mildness, obedience, industry, and temperance. To some extent, the “admonishers” whom Blake was to satirize in The Song of Los (1795) resemble her, especially those admonishers who “restrain the child . . . That the remnant may learn to obey, [and] / That the pride of the heart may fail . . . ” (6:19-7:3). Closer in time to the publication of the second edition of Original Stories, Blake’s “Nurses Song” (in Experience) presents another accuser of sin like Mrs. Mason. The nurse’s language implies that the children for whom she is responsible are either wasting their youth at play or up to something, whispering “in the dale” (E 23, 11. 2, 7). Because of her suspicions she believes, as D. G. Gillham says, that the children “must be

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Mrs. Mason strives to teach Mary and Caroline moral virtue by focusing their attention not only on their shortcomings but also on the “real” world. Unlike the tutor in Ëmile she is mirthless, heaping excessive care on her charges. For example, she tries to inculcate patience and long-suffering by introducing the girls to Mrs. Trueman, who has retained her moral values despite having been grossly cheated by Lady Sly (p. 49). Mrs. Mason attempts to teach her charges kindness by telling them about one man who drowned his dog’s litter (p. 18) and about another who “let two guinea-pigs roll down sloping tiles, to see if the fall would kill them” (p. 18). As the last two examples indicate, some of the experiences to which the governess introduces her charges are scarcely appropriate or edifying. Although they make mistakes, Mary and Caroline are neither heartless nor cruel. They would hardly learn mildness and self-control by hearing about Jane Fretful, who threw a stool and unintentionally killed her pregnant dog because it had taken a piece of her begin page 8 | ↑ back to top food (pp. 33-34), or about Mr. Lofty, who killed himself after duelling with a man he thought had insulted him (pp. 134-135).

As most of the experiences that Mrs. Mason deals with are in some way negative or unhappy, Blake devoted three of his five rejected designs and five of his six engravings for Original Stories to them.11↤ 11 W. Clark Durant’s edition of William Godwin’s Memoirs of Mary Wollstonecraft (1927; rpt. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1969) includes copies of the rejected and used designs for Original Stories. All of his engravings for the novel reveal together his strongest response to the governess’s dour perspective. For the most part, however, the illustrations have been disregarded by Blakeans as either “native and rude” or “competent” but “conventional and uninspired.”12↤ 12 Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, 2nd ed. (London: John Lane the Bodley Head, n.d.), p. 92; Jean Hagstrum, William Blake: Poet and Painter (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1964), p. 119. Differing with such views, Roger Easson and Robert Essick suggest that the engravings ought to be studied closely.13↤ 13 Easson and Essick, p. vii. The engravings studies here are from the 1791 edition of Original Stories. I agree. The illustrations were among Blake’s early original copper-plate engravings. It is likely that he would have done them well to secure further work for himself, but more importantly to complete his original designs. He despised the separation of design work from engraving and believed, as Morris Eaves says, that “the artistic process is a perfect combination . . . of conception and execution. . . .”14↤ 14 Morris Eaves, “Blake and the Artistic Machine: An essay in Decorum and Technology,” PMLA, 92 (1977), 909. The engravings, then, are not hack work. On the contrary, they are subtle, ironic, and revealing. Except for the frontispiece, which is introductory in nature, they depict stories and situations whereby Mrs. Mason pushes Mary and Caroline more and more directly into experience.

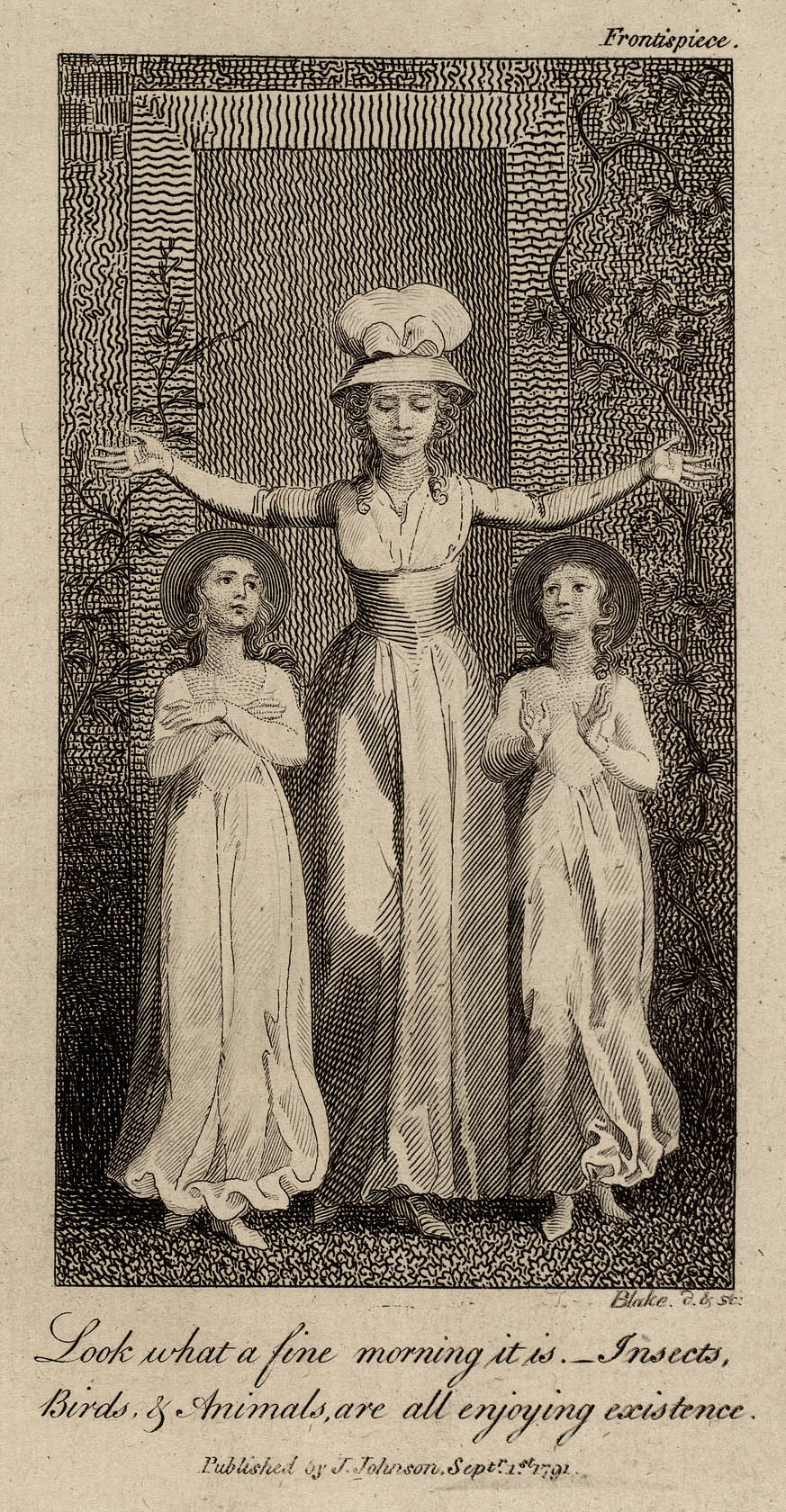

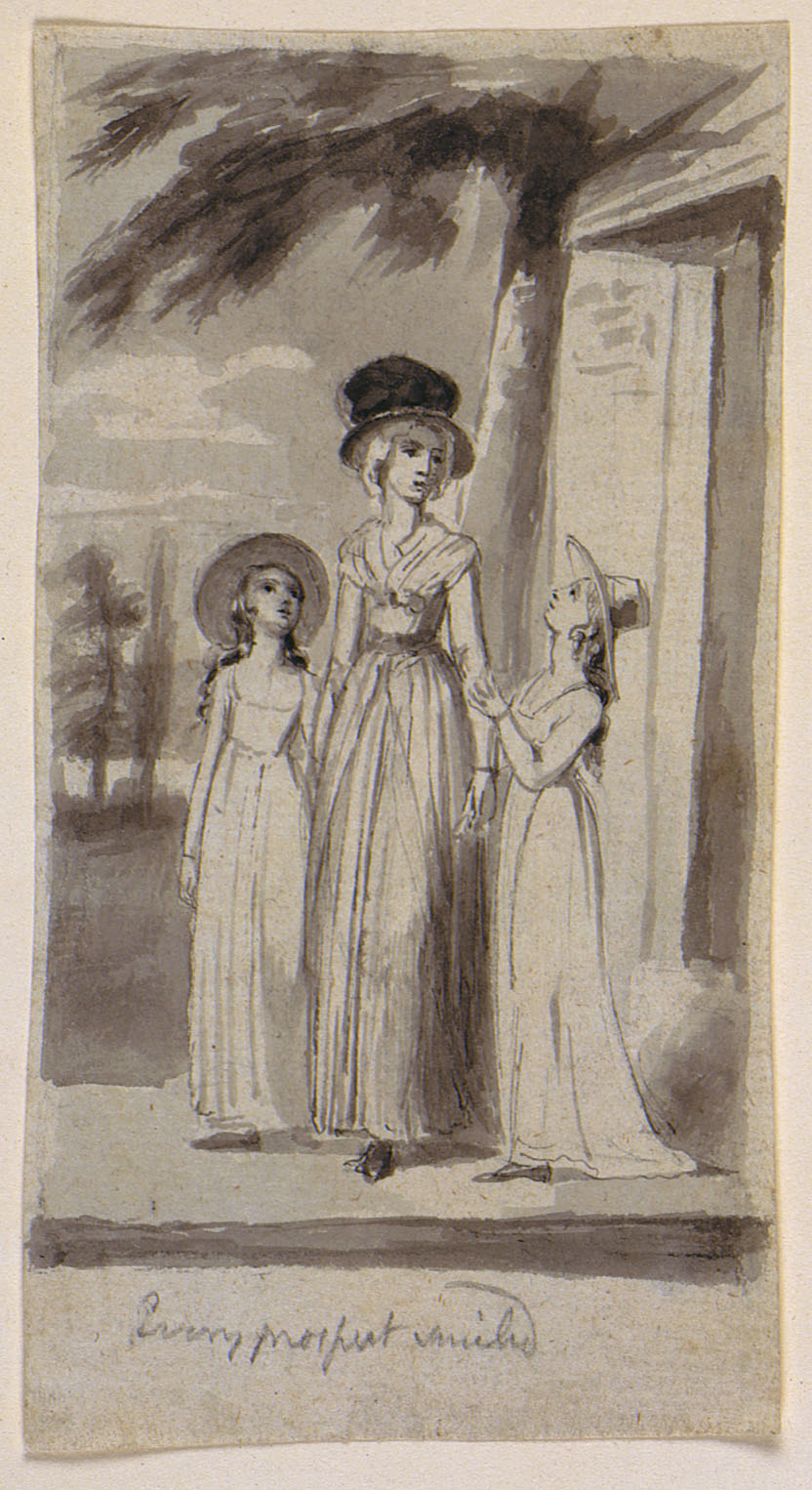

According to David Erdman, Blake parodied the frontispiece (illus. 4) in his illumination for the “Nurses Song” of Experience (illus. 5), which depicts a governess assisting one of her charges just outside a doorway (The Illuminated Blake, p. 80). Indeed, there are images in the frontispiece that are parodied. Furthermore, there are details in it that are ironic. The plate shows Mrs. Mason with her charges in front of a doorway. They are beginning to take a walk. And the governess’s influence is beginning to reveal itself as the nurse’s does in the illumination of Blake’s lyric. Mary and Caroline appear uniform and neatly groomed (like the boy in the design for “Nurses Song”). The girls’ hats, which look a little like halos, imply the virtue and probity that they are supposed to learn under their teacher’s direction. But the girl on the right is out of step with her sister and the governess. And the children’s hands are in different positions, indicating perhaps different degrees of repressed vitality (like the boy’s in Blake’s poem). Despite the engraving’s subscription (words that Mrs. Mason speaks in Chapter I), there is little spontaneity or joy here. The children and their guardian are not smiling although they appear to be doing so a little in the preliminary drawing for the frontispiece (illus. 6). The governess is not even looking upward or outward at the “fine morning” but instead downward watchfully at her charges. She holds her arms outstretched not in joy but as if to present Mary and Caroline to the world. Having turned the girls’ eyes and heads slightly toward her, however, Blake foreshadowed their inevitable dependence on her. He implied similar dependence in a rejected drawing entitled “Every prospect smiled” (illus. 7), which involves the same

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

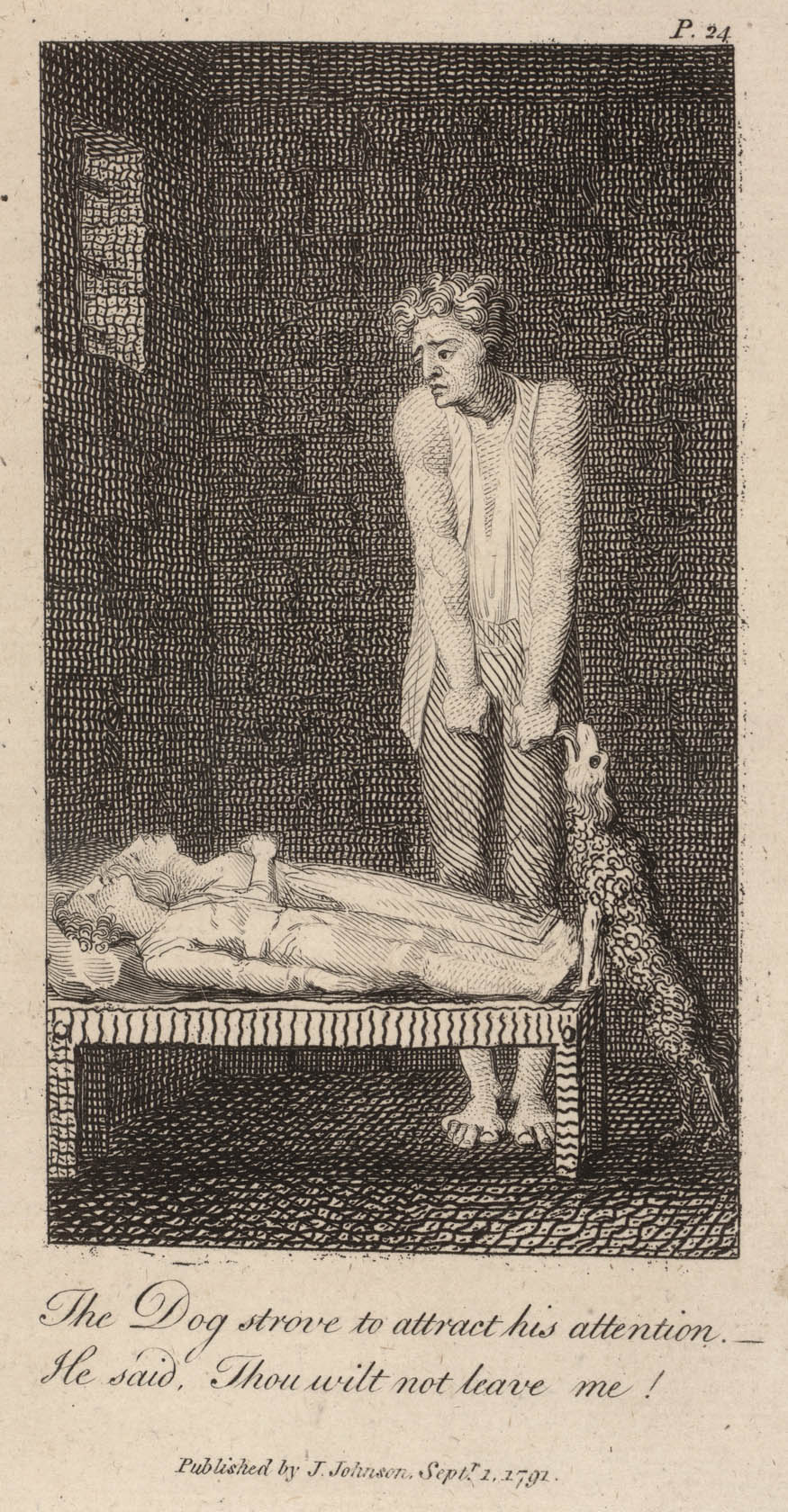

The second plate in the novel (illus. 8) depicts part of a tragic story that Mrs. Mason tells Mary and Caroline. The story concerns a man named Robin, who fell into debt, went to jail, and lost his wife and two of his four children to poverty and disease. His remaining children and the family dog joined him in jail, but soon afterwards the children died of a fever. They lie on a bed in his cell. To present the woeful image that Mrs. Mason tries to create in Mary’s and Caroline’s minds, Blake stayed fairly close to the verbal description: “The poor father . . . hung over their bed in a speechless anguish; not a . . . tear escaped from him, whilst he stood, two or three hours, in the same attitude, looking at the dead bodies of his little darlings. The dog licked his hands, and strove to attract his attention . . . ” (p. 23). Blake’s engraving illustrates this man’s grief perfectly. Robin stands rigidly with his shoulders drawn up, his arms held straight down in front of him, and his hands closed in fists. His gaze, while more poignant and less horrified than in the preliminary drawing (illus. 9), is fixed on his children. All of these details suggest a prolonged contraction of grief. Few signs of hope appear in his cell—only the prayerful position of one of his children and the consoling lick of Robin’s hand by his dog. One wonders why the governess tells Mary and Caroline about this man and his family, except to make her charges conscious of life’s cruelty and misfortune. She draws no specific moral, except the implicit one of being charitable to debtors; but her example is much too extreme for her audience. Despite the grief and hopelessness in this story, Blake captured something in Robin’s stance and gaze that Mrs. Mason finds pathetic—namely, his determination or will to believe in life regardless of the evidence before him. At the end of his contraction of grief, he says to his dog, which he later calls by his children’s names: “thou wilt not leave me . . . ” (p. 23).

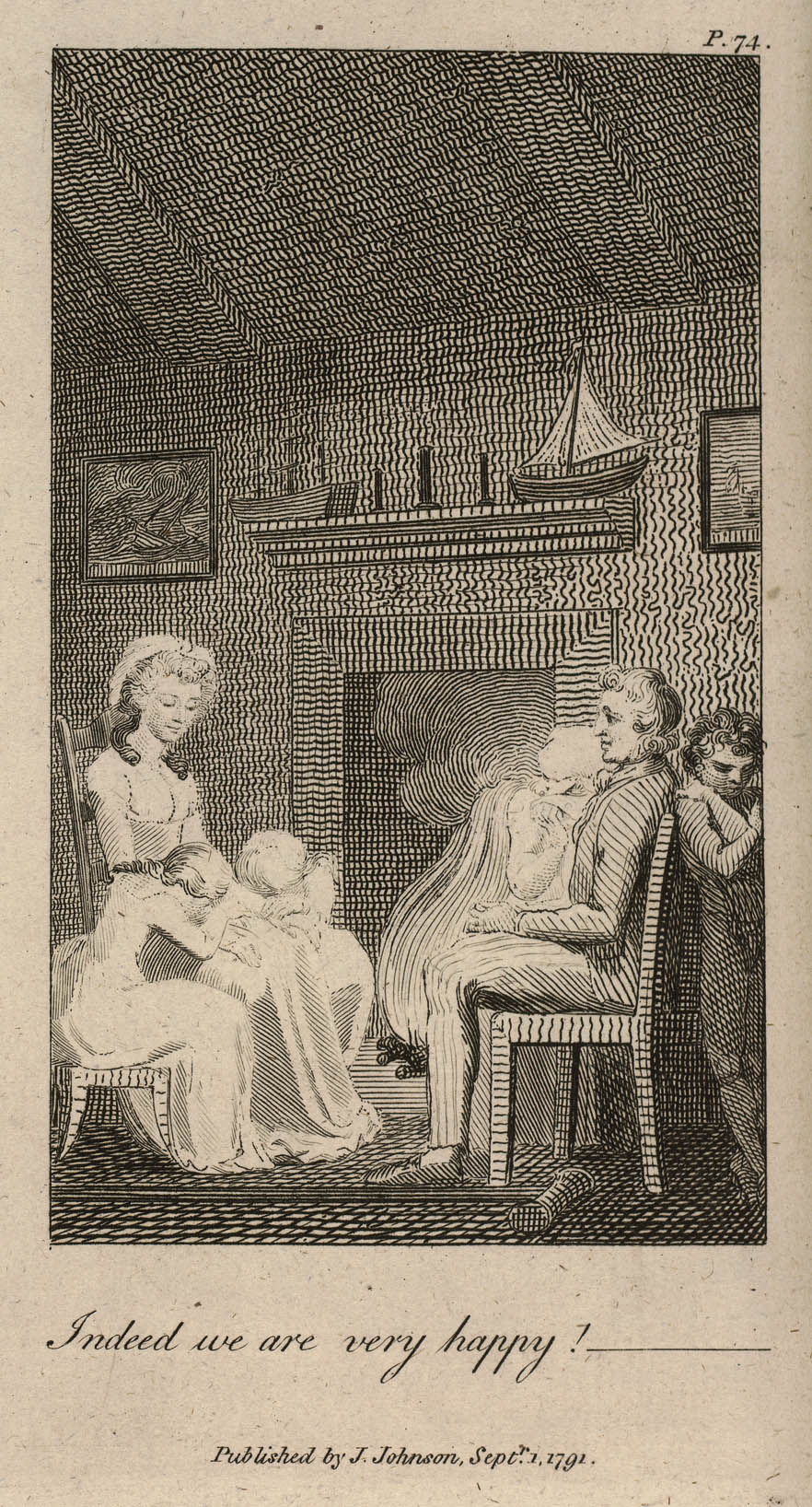

begin page 10 | ↑ back to topThe third engraving in Original Stories (illus. 10) shows the governess and her charges in “honest” Jack’s cottage, listening to tales about his life as a sailor—tales of imprisonment, shipwreck, and personal injury. Mrs. Mason wanted the children to hear about his experiences, for she had heard about them before and undoubtedly considered them edifying in light of his assertion that he and his family are now “very happy” (p. 74). Blake, however, did not emphasize this moral so much as his interpretation of the children’s reaction to it and of the adults’ reaction to them. Satirizing the theme of misery leading to happiness, the illustration shows Mary, Caroline, and Jack’s family grieving about his stories. (The novel says nothing of this.) The plate is critical of Mrs. Mason and especially Jack; they sit back unresponsive to the children’s distress. The governess watches her charges calmly, her hands not even turned up in support of them as they cry in her lap. Jack is even less supportive as he sits stiffly with his hands in his lap, looking at Mrs. Mason, ignoring Mary’s, Caroline’s, and his family’s sorrow. As if retelling his experiences were not enough (we get the impression that he cannot forget them), on the wall to the left of his fireplace is a picture of a sinking vessel—a constant reminder to his family and visitors that the world is a dangerous place.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

In the fourth plate (illus. 11), Blake illustrated the governess trying to make her charges confront a scene in experience directly. The scene is a ruined estate once owned by Charles Townley, a young man who continually procrastinated and as a result lost a fortune and the chance to help a friend in dire need. Blake’s illustration is gloomy and ominous with trees that overhang and twine serpent-like in the setting—trees that contrast with the opening plate’s foliage which dances innocently upward (illus. 4) and which Mary and Caroline enjoy very little of. Less detailed than the description in the text, the fourth plate emphasizes not so much Townley’s estate as the girls’ reaction to mutability and Mrs. Mason’s response to them. Faced with this setting and the story behind it, the girl on the right leans against the governess for comfort. Mrs. Mason holds her reassuringly but mostly (I think) in attention to the scene.15↤ 15 In The Engravings of William Blake (1912; rpt. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1968), p. 58, Archibald G. B. Russell says that the girl “trembles . . . and is gently reproved by Mrs. Mason, who . . . clasps her to herself.” The governess’s right foot suggests that she may be about to step back as if to anticipate this girl’s retreat (her right heel is also visible) and her increased distress like that of the other girl, whose hand Mrs. Mason holds. This situation is similar to an earlier one in the novel, wherein both “children turned away” from another view of experience—the sight of a bird shot down by a young boy (p. 7). In spite of the girls’ distress, the governess insisted that they “look at” the bird and learn how much suffering there is in life.

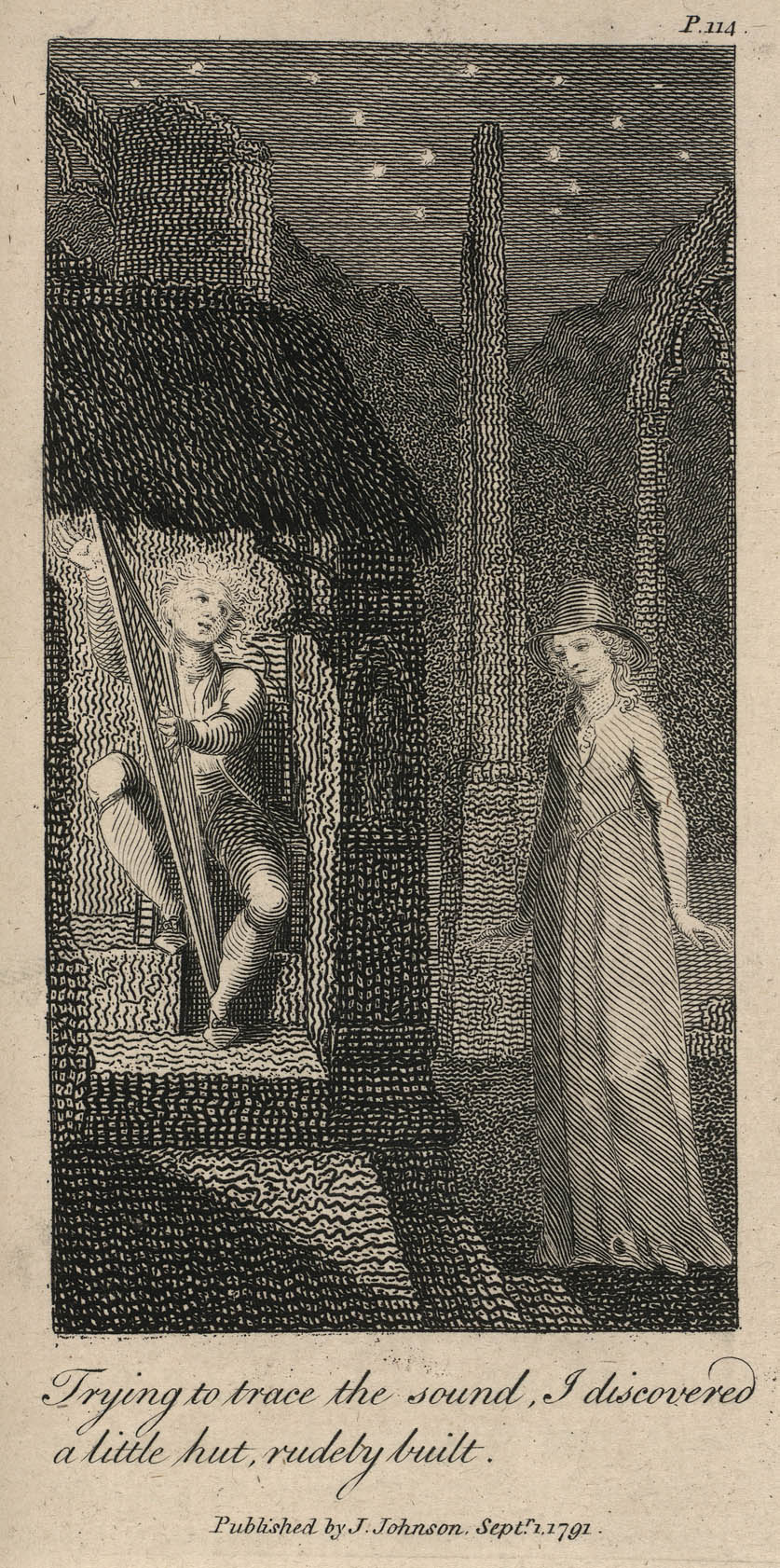

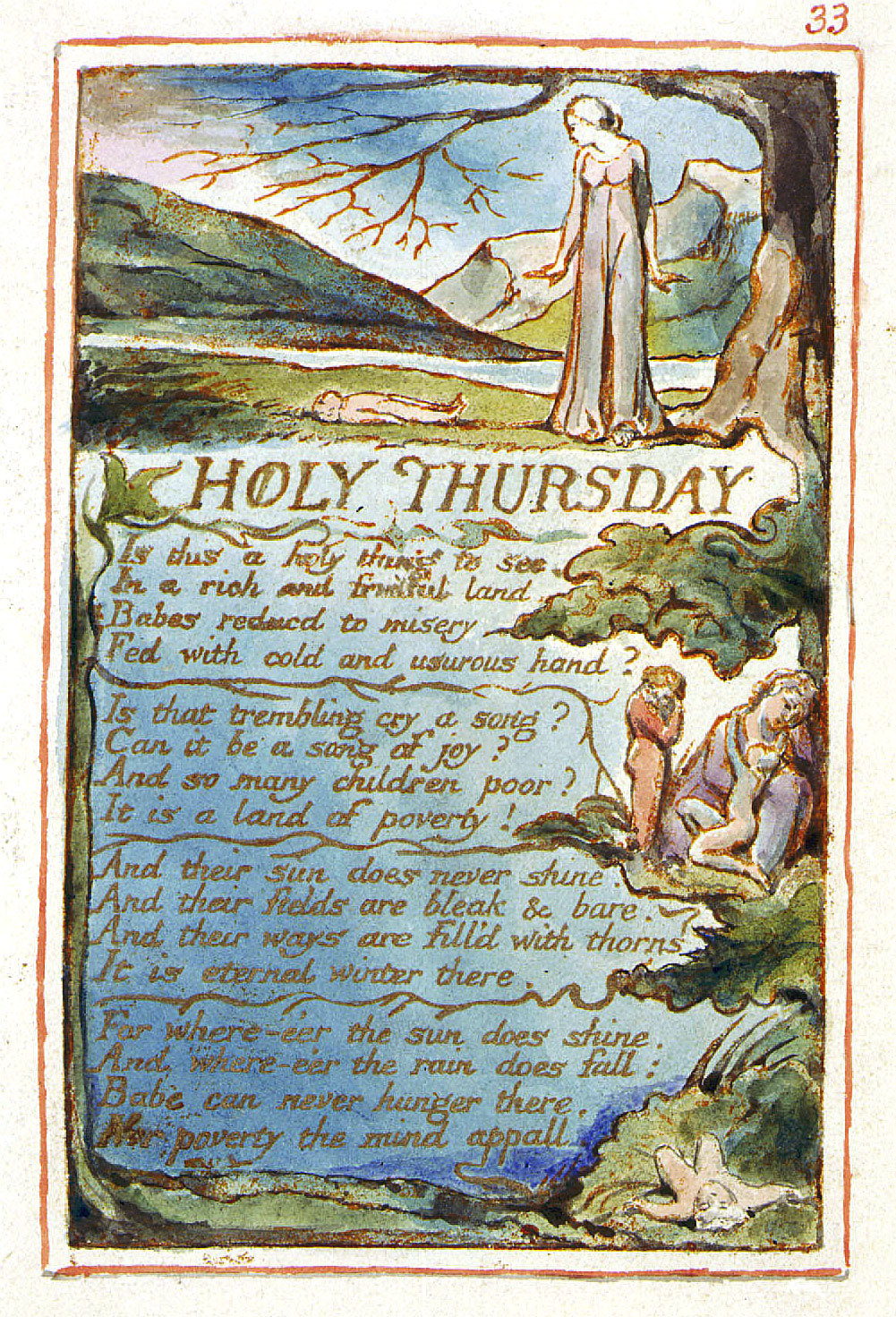

The fifth engraving in Original Stories (illus. 12) deals with one of Mrs. Mason’s own experiences, which she tells Mary and Caroline. Like the previous illustration this one emphasizes the governess’s concern about mutability (p. 119). During a trip through Wales she was detained “near the ruins of an old castle” (pp. 113-14). While pondering the castle, she heard the sound of a harp, and tracing that sound she came upon “a little hut, rudely built” (p. 114). Like the “desolate” castle (and the estate depicted in the previous plate), the harper’s abode was dilapidated (pp. 114-15). Blake’s engraving suggests hesitancy in Mrs. Mason’s approach to that abode—hesitancy born out of her apprehensions about the scene.16↤ 16 In the fifth plate of the 1796 edition of Original Stories, Mrs. Mason’s “eyes have been partly closed” (Easson and Essick, p. 12). Her hands, positioned anxiously at her sides, resemble those of the woman at the top of “Holy Thursday” (in Experience), which also presents a desolate landscape (illus. 13). The position of the governess’s hands contrasts sharply with that in the frontispiece (illus. 4), where her hands imply receptiveness and acceptance, and in plates 3 and 4 (illus. 10 and 11), where her hands encourage these traits in her charges. This contrast suggests her fears and perhaps some hypocrisy. In spite of the decrepit condition of the harper’s abode, the difficulties in his life (p. 117-118), begin page 11 | ↑ back to top and his “old” age (p. 115), Blake portrayed him as an inspired young man sitting in a shaft of light, his hair ablaze while he plays his instrument.17↤ 17 Erdman (Blake, p. 181) and Laurence Binyon (The Engraved Designs of William Blake [1926; rpt. New York: Da Capo Press, 1967], p. 40) note the difference in age between the harper in the text and the harper in the engraving. Binyon feels that Blake “put more of his own spirit [into the plate] than into the rest of the set” (p. 40). The engraver’s perception indeed contrasted with Mrs. Mason’s. According to her story, the meeting with the harper was “providential” (p. 119), but that was only because she was able to extend to him her charity—not because she perceived (as Blake did) his imaginative power which enabled him to play both the melancholy strains of experience (p. 118) and the delightful melodies of innocence (p. 119).

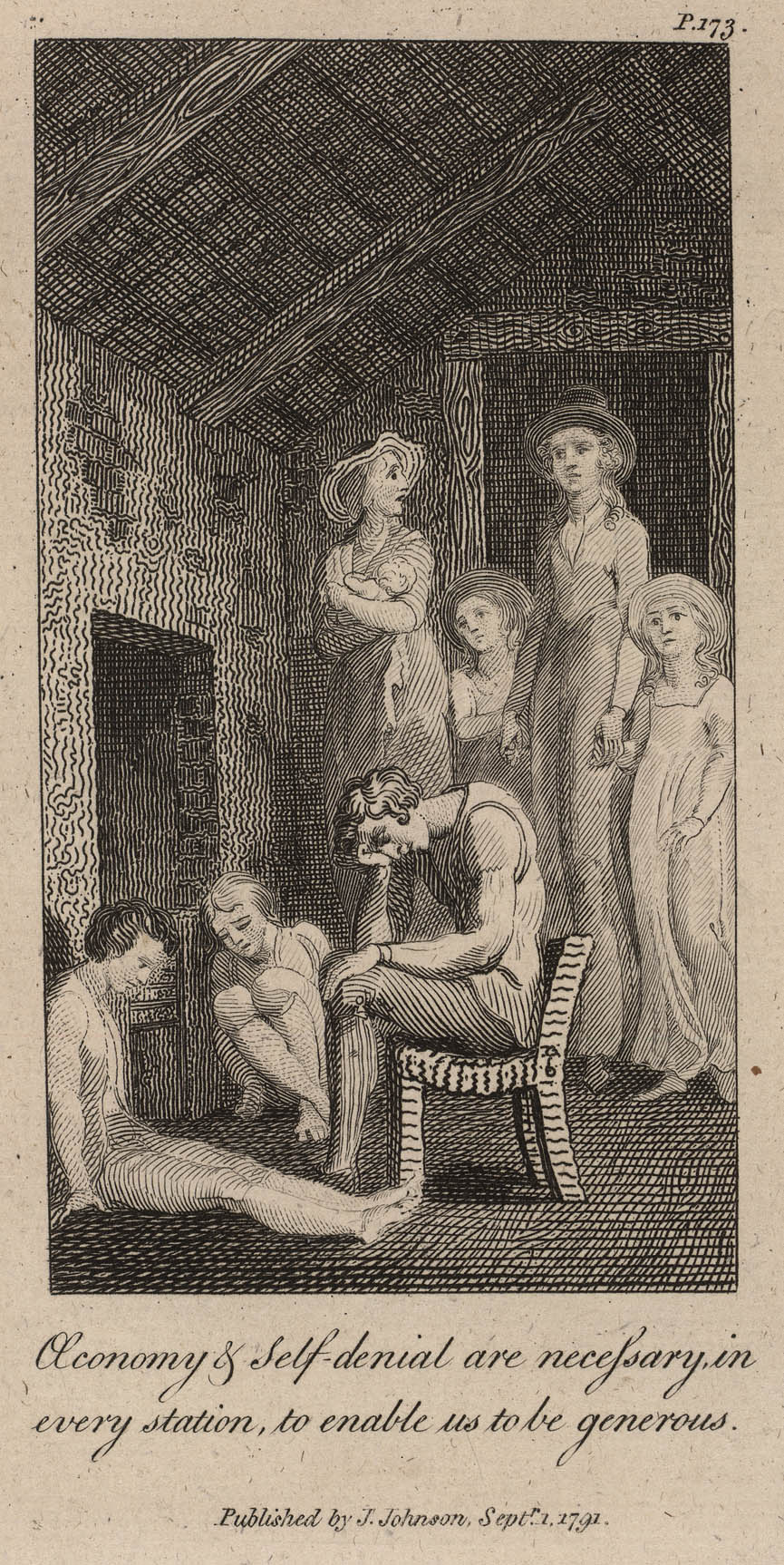

The sixth and last plate (illus. 14) depicts appropriately the culmination of Mrs. Mason’s effort to expose Mary and Caroline to experience, for here they face directly a poor family in despair. Like several “edifying” situations in the novel, this one is arranged by the governess. Caroline has just spent the last of her money during a visit to London. To show the child that “prodigality and generosity are incompatible” (p. 173), Mrs. Mason asks a poor woman to take them to her family, which lives in a filthy garret. The focus of Blake’s plate is on the family’s suffering and Mary’s and Caroline’s recognition of it. According to the narrator of the novel, the father in this family is ill and out of work (p. 170). The illustration shows him sitting despondently in a chair. His muscular body suggests that he has done a great deal of work and could do more—if he were well and there were any work available. In front of him two of his children sit on the floor, one of them huddled in misery on one side of a grate while the other on the opposite side of the grate stares blankly into his lap. For these children this is no world of innocence: “The gaiety natural to their age, did not animate their eyes. . . . Life was nipped in the bud; shut up just as it began to unfold itself” (p. 172). These children look as unhappy as “honest” Jack’s family in plate 3 (illus. 10). In plates 3 and 6 Blake portrayed similar and contrasting details such as the unhappiness in each, Jack sitting upright in a chair while the poor man sits slumped over in his, and the ample furnishings and fire in Jack’s living room versus the starkness of the poor man’s. Blake’s aim in depicting these comparisons and contrasts was probably to help us see that the preoccupations of a parent like Jack and the situation of one like the poor man can consign their families to the same condition—unhappiness.

Standing with an infant in her arms, the mother in plate 6 presents the most disturbing image in her family. The floppy brim of her hat indicates its age and her poverty. With her mouth open and the look of fear in her face, she stares at Mrs. Mason as if to ask what is going to happen. The situation is truly grim. As the governess looks on somberly, she holds one hand of each of her charges. The girl on the left appears uneasy, her mouth contracted in a frown and her head tilted to the side and slightly back. The girl on the right appears dismayed, her eyes wide open and staring at the misery in front of her. The gesture of this girl’s left hand may hint at a desire to offer some comfort; but the gesture is too constrained and therefore ineffective.

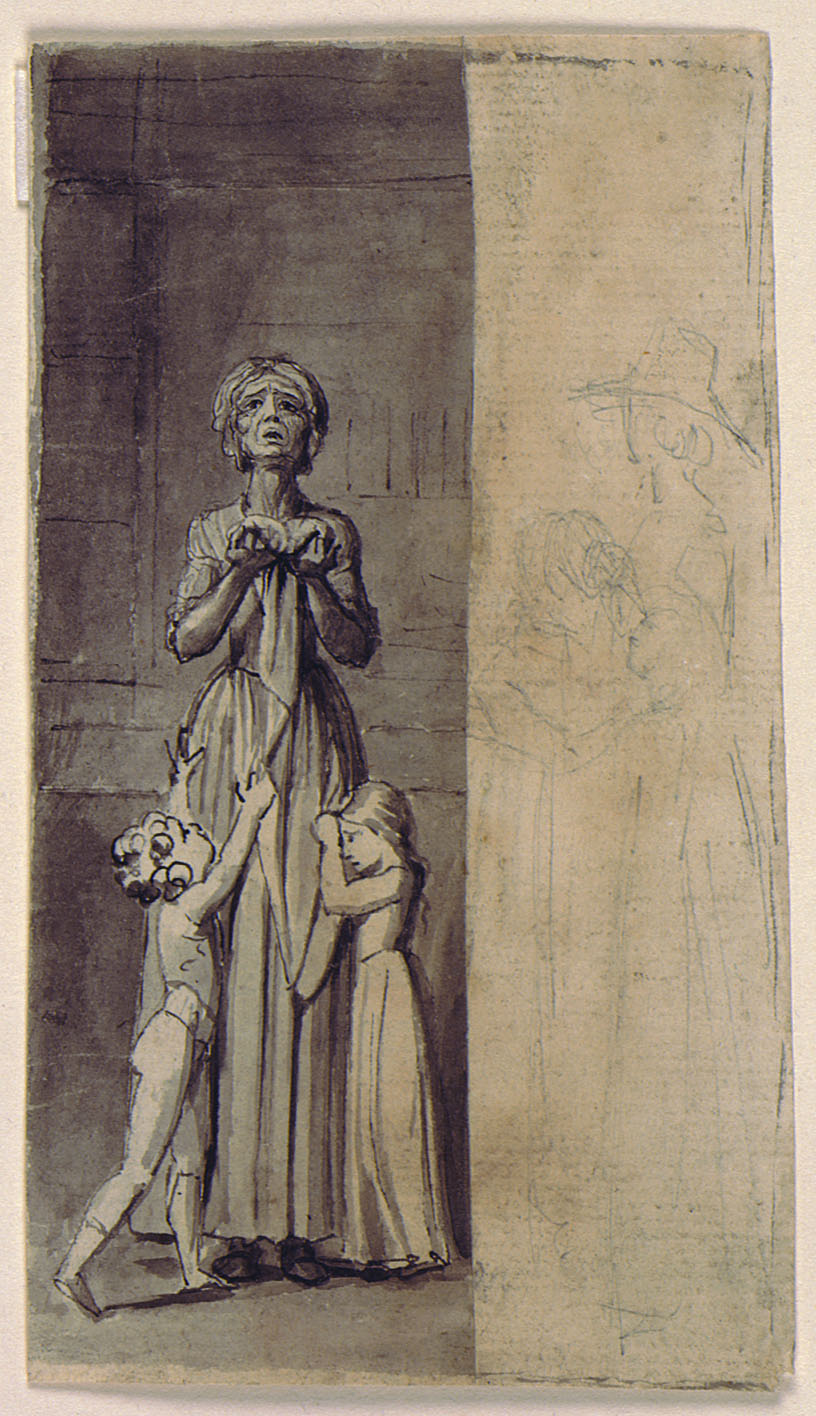

Blake may have also produced an unnamed and unused drawing concerning the visit to London by Mrs. Mason and her charges (illus. 15). It appears to deal with an elderly woman, possibly the “distressed stationer” whom the governess and Mary and Caroline visit. The stationer is distraught with the burden of her grandchildren and a declining family business, her son having been jailed for debt and her daughter-in-law having died (pp. 165-68). The drawing seems to picture the stationer with her grandchildren at her side and a cloth clutched in her hands, her face turned upward in misery.18↤ 18 A copy of a wood-cut of this drawing appears in Gilchrist, p. 91. A faint outline of Mrs. Mason’s profile appears to be on the right-hand side of the drawing where she observes another example of human suffering.

As a result of Mrs. Mason’s influence these girls learn about the “real” world. By the

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The Good are attracted by Mens perceptions

And Think not for themselves

Till Experience teaches them to catch

And to cage the Fairies & Elves. . . .

(E 490, 11. 1-4)

Mrs. Mason inculcates in her charges what the psychologist Jean Piaget would call “moral realism”—a kind of literalism that tends “to regard duty . . . as self-subsistent . . . as imposing itself regardless of the circumstances in which the individual may find himself.” According to Piaget, moral realism involves obedience to authority and the judgment of others according to their conformity with established rules and not according to their intentions. For Blake such realism is repressive: “One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression.” As the author of “The Little Black Boy,” “The Chimney Sweeper” (in Innocence), “Infant Sorrow,” and “A Little Girl Lost,” the poet recognized some of the consequences of this kind of realism: prejudice, child labor, and suffering.

In discussing moral realism Piaget says that when children have moral “stories” told to them (as Mary and Caroline often do), they “will . . . make judgments devoid of pity and lacking in psychological [Blake would use the term ‘imaginative’] insight. . . .” Thus, in accordance with Mrs. Mason’s stories and example, her charges begin to judge wrongdoing strictly and inflexibly. In moral realism, in moralism, there is a certain arbitrariness, an egocentrism (Piaget’s term).19↤ 19 The Moral Judgment of the Child, trans. Marjorie Gabain (New York: Free Press, 1965), pp. 111-112, 185, 33-34. Hence, even in her almsgiving the governess is egocentric—unable to get beyond her narrow perspective: “ . . . we exercise every benevolent affection to enjoy comfort here, and to fit ourselves to be angels hereafter . . . ” (p. 13). By the end of Original Stories, Caroline and Mary reflect their guardian’s self-concern and self-righteousness. Caroline is embarrassed because she has only her scarf to give the family depicted in plate 6 (illus. 14), whereas Mary has the rest of her spending money to give them and is “proud” of her “privilege” (p. 172). The significance of such self-righteousness, which adults often exemplify to children, did not elude Blake, who eventually called it “Satanic.”

In contrast to Mrs. Mason’s oppressive and self-righteous attitudes toward others, particularly children, Blake’s were much more positive. As S. Foster Damon says, for Blake “Children symbolize the fecundity of the imagination, the ‘Eternal Creation flowing from The Divine Humanity in Jesus.’”20↤ 20 A Blake Dictionary (Providence, R. I.: Brown Univ. Press, 1965), pp. 81-82. In a letter to Dr. Trusler (23 August 1799), Blake declared that “a vast Majority” of children possess “Imagination or Spiritual Sensation” (E 677). And in a poem describing one of his visions to Thomas Butts (2 October 1800), he suggested that to see as a child while an adult enhances the visionary experience: “I remaind as a Child / All I ever had known / Before me bright Shone” (E 684, 11. 72-74).

Even though most of Mrs. Mason’s views are negative (especially those concerning youth), not all are so from a Blakean perspective. For example, she urges Mary and Caroline to be considerate of all creatures and to base every friendship on truth. Blake certainly would have agreed with these ideals, for he was soon to complete poems like “The Fly” and “A Poison Tree” (both of Experience). As the author of “On Anothers Sorrow” (Innocence), he would have agreed also with the governess’s charity to the poor, though it sometimes appears to be self-serving (“While we impart pleasure we receive it”).

One of Mary Wollstonecraft’s biographers has suggested that the novelist and Mrs. Mason are similar, but the two are actually different.21↤ 21 Emily W. Sunstein, A Different Face: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), p. 161. For the principal differences between the novelist and Mrs. Mason, see Ralph M. Wardle, Mary Wollstonecraft: A Critical Biography (Lawrence: Univ. of Kansas Press, 1951), p. 89. I think that Blake as a creator of various characters and personae would have recognized the differences between Mary and the governess. According to Edna Nixon, several of the ideas and attitudes expressed in Original Stories were not “mature” Wollstonecraft.22↤ 22 Mary Wollstonecraft: Her Life and Times (London: J. M. Dent, 1971), p. 56. See E. V. Lucas’s Introduction to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories (1906; rpt. Folcroft, Pa.: Folcroft Library Editions, 1972), pp. iv, x. Indeed, her goal and strategy in writing the novel troubled her. On the one hand, she favored conveying knowledge gradually to children (p. iv). On the other, she wished to impart “premature knowledge” to them and thereby compensate for some of the parental neglect in her society (p. v). Her attempt to recommend the novel to adults as well as children did not resolve, however, the “objection” which she expected against it, namely, that its “sentiments are not quite on a level with the capacity of a child” (p. v).

Like Wollstonecraft, Blake understood the importance of living in experience. Thel’s failure to do so is tragic. Such failure risks prolonging innocence to the point of narcissism, whose dangers are as great as those of experience. But to try continually to confront experience creates risks, too, especially the risk of becoming what one beholds. This could stifle whatever energy and begin page 13 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Struggling in my fathers hands:Like these words, Enitharmon’s in Europe consist of a warning, though she probably does not intend them as such, that concerns both the sexual and the psychological education of not only young begin page 15 | ↑ back to top girls but everyone:

Striving against my swadling bands:

Bound and weary I thought best

To sulk upon my mothers breast.

When I saw that rage was vain

And to sulk would nothing gain

Turning many a trick & wile

I began to soothe & smile. . . .

(E 28, 11. 5-8; E 720, 11. 9-12)

Forbid all Joy, & from her childhood shall the little female

Spread nets in every secret path.

(6:8-9)