REVIEWS

Flaxman at the Royal Academy

David Bindman, ed. John Flaxman. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1979. Pp. 188. 260 monochrome illus. & 4 color plates & 99 comparative illustrations. £7.50. Published simultaneously by Thames & Hudson, London, £12.50.

Anyone who missed the Flaxman exhibition but wanted a lively introduction to the man and his works might be well (if anachronistically) advised to begin with a replay of the Schorn interview, extracts from which are given in the exhibition catalogue. The German art historian and journalist Ludwig Schorn visited the aging sculptor in the spring of 1826; from notes made at the time, he compiled reminiscences published as a series of three articles in the Kunst-Blatt a year later, after Flaxman’s death.

Schorn presents his encounter with Flaxman with a skill which many of our contemporary television interviewers might learn from. Having long admired Flaxman as the draughtsman of those outlines to Homer, Aeschylus and Dante which, through engravings, had already secured Flaxman’s European reputation, Schorn secures a personal introduction to him. Arriving in London, he prepares for his interview by going to see (and through his enthusiastic but not uncritical descriptions showing us, almost as if he had a television camera at his command) works by Flaxman currently on display: sculptures such as the Nelson Monument in St. Paul’s and the Mansfield Monument in Westminster Abbey, models for busts of Raphael and Michelangelo in the Royal Academy’s newly-opened exhibition, and, in the silversmiths’ shop on Ludgate Hill of Messrs. Rundell & Bridge (“suppliers of costly and tastefully executed deluxe vessels”) a copy of the Achilles Shield. Ornamented with episodes from the Iliad and acclaimed as a “masterpiece of modern art,” designed and modeled by the master himself but cast and chased in metal by the firm’s workers, four replicas had already been made in silver, for the King, the Duke of York, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Lonsdale (“gilded, the article costs 2000 pounds, ungilded 1900. In bronze it is to be had for 450 pounds . . . ”). Having done his ground-work, Schorn goes to Flaxman’s house off Fitzroy Square (“a small, simple house, but nice and well-kept”: just what one might expect from a plain-living Low Churchman) to meet the great man himself. After a short wait in the drawing-room, “a very small, thin and exceedingly hunched man” came in (Flaxman, never robust, had been a cripple from youth). Schorn quickly perceives that this unprepossessing exterior radiates “mildness,” “seriousness” and “sweetness of conduct.” He begins by avowing his long admiration for Flaxman’s outlines to Homer and Aeschylus:[e] Flaxman remarks that they have been over-praised, adding that artists who imitated them (and they were by now as much part of an artist’s training as Le Brun’s Physiognomy) “would have done better to follow nature.” Schorn leads Flaxman on to his role as Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy: Flaxman declares that his purpose both as artist and teacher has been to show that “Art in Christianity can rise higher than in paganism, since Christian ideas are more sublime than pagan ones.” Cut to Flaxman’s workshop, where the sculptor uncovers a clay model of the figure of Hope, “still damp,” on which he is currently working: Schorn notes the sensitivity of the modeling, which achieves tenderness without sentimentality.

Discussion of Flaxman’s art then develops along two main lines: the relative importance of classical and Christian themes in his art, and the extent (if any) to which he worked from nature. Admiring two small reliefs of Justice and Innocence in the workshop, Schorn praises the naturalness and simplicity of their poses, and exclaims “One sees here how the gifted mind may find enough beauties begin page 23 | ↑ back to top and motives in nature, and once arrived at the realization of beauty, have no need to imitate the ancients.” He has struck absolutely the right chord: “in a particularly melodious voice and with a cheerful look which seemed to project the inner-most depths of his soul,” Flaxman responds with his credo: “The works of God are always better than the works of man, and nature, even if imperfect in particulars, still remains forever unattainable. The artist unites in his works the most beautiful he has seen in it: yet it is not the beauty of nature that is the highest but that of the idea . . . All the beauty which we can portray is . . . individual, not merely because it appears only individually in nature itself, but because it also results from the character peculiar to the artist and is, as it were, the blossoming of noble powers which are laid on him and which he must carefully preserve and develop.”

Chief honor for initiating and presenting an exhibition in which Flaxman’s “noble powers” were shown in all possible aspects belongs to Ludwig Schorn’s latterday compatriot Dr. Werner Hofmann, Director of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, where the exhibition was first shown (20 April to 3 June 1979) as one of Professor Hofmann’s great series of exhibitions devoted to “Kunst um 1800.” It was then seen at the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen, and finally (26 October to 9 December 1979) at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Professor Hofmann was fortunate in being able to count on the assistance of Dr. David Bindman, both in helping to select an exhibition of 260 works and (no doubt a heavier task) in coordinating the work of thirteen Flaxman scholars in his capacity as editor of a catalogue which now becomes the most comprehensive work on Flaxman ever published.

In his introductory essay, Dr. Bindman predicted that the chief surprise for visitors to the exhibition would be the range of Flaxman’s activity. It was certainly true that the stuff of the objects shown ranged from paper through plaster and wax to marble, and from pottery to bronze, silver and gold; and each of the materially-different sections of the exhibition, which included “Flaxman as sculptor,” “Flaxman and Wedgwood,” “Flaxman and designs for medals and coins” and “Flaxman as a designer of silverwork,” was intelligently selected and catalogued. But two reservations concerning “the range of Flaxman’s activity” insistently obtrude themselves. First, although Flaxman’s style is invariably graceful and often moving, it was not profoundly original in inspiration. Its elements were taken initially from his study of Greek vase painting, Roman sarcophagi and Gothic sculpture: Flaxman’s own contribution lay in deploying these elements, freshly and inventively, in sensitive and restrained designs infused with moral sentiments. Secondly, “the range of Flaxman’s activity” does not mean that all the works connected with his name (even the products of his own sculpture workshop) were produced by his own hand. Flaxman was in fact primarily a designer. He was always aware, in whatever he drew, that he was designing potentially plastic shapes: but through whose hands and in what various materials they took eventual form was of less importance to him than the cultivation

We first see Flaxman’s designs taking shape in the hands of Wedgwood’s potters. Wedgwood & Bentley opened their factory at Etruria in 1769, aiming to produce ornamental wares in a “truer antique taste.” A few years later, scouting for talent among London plaster-cast makers (of whom Flaxman’s father was one) in the hope of finding something “less hackneyed” than the usual copies or squeezes from classical, French or Italian sources, Wedgwood found that young Flaxman could produce remarkably elegant designs which, though chiefly variations on the classical theme, had a new grace and simplicity which connoisseurs such as Sir William Hamilton pronounced to be in the “true simple antique style.” Flaxman was to work for Wedgwood for some fifteen years, the connection providing him with financial stability through the 1770s and 1780s and making possible his departure for Italy in 1787.

The minimal extent to which Flaxman was involved in the actual production process is succinctly summarized by Bruce Tattersall, former Curator of the Wedgwood Museum. Flaxman would send Wedgwood a drawing of his proposed design; Wedgwood would return it with notes of any necessary alterations. “Flaxman would then send Wedgwood a wax model of the design. At this stage Flaxman’s involvement would cease. Once Wedgwood obtained the wax it became his property and he could do as he wished with it.” Specialist modelers at Etruria would adapt the wax for reproduction, frequently simplifying or breaking up the design into component parts. Whether Flaxman’s designs for Wedgwood eventually materialized in blue, green or lilac jasper or in black basalt, or whether his design of “The Dancing Hours” was used to decorate a rum kettle or a salt cellar (examples of both were exhibited) was beyond Flaxman’s control; luckily it also seems to have been beyond his concern. Similarly with his designs for coins, medals and silverwork; the executants were craftsmen whom Flaxman in most cases never encountered. In these sections, then, we chiefly saw Flaxman’s work at one remove, and not always to full advantage, just as Schorn had seen the Achilles Shield, sensing that the thing was “permeated by a genuine spirit of antiquity,” but left wondering to what extent a “somewhat superficial” execution betrayed the absence of the master’s hand.

“The master’s hand” was not even responsible for the final form of the monumental sculptures which provided Flaxman with most of his commissions. The point is fairly made by Mary Webster in her essay on “Flaxman as sculptor” (pp. 100-01). “Greatly admired for his sensitive work with the modelling tool, Flaxman was less adept with the chisel and he worked very little on the actual marbles; he adopted, in fact, the pernicious practice of handing over the entire execution of the marble to workmen in his studio. The sometimes flat and dull execution which resulted robs more than a few of his marbles of the merit of a fully-realized execution.” But as she points out, there was an intermediary stage between the design and the execution by which Flaxman’s gifts as a sculptor should more fairly be judged. This stage was the fashioning, in Flaxman’s own hands, of a small sketch-model in clay, later cast in plaster.

It is in these sketch-models that Flaxman’s sensitivity and poetic gifts as a sculptor are most fully demonstrated. He himself realized that these models were the fullest expression of his powers, for he kept them in their hundreds round the walls of his studio (they are now chiefly in the collection of University College, London). A judicious selection of them was exhibited, including the model for “Come thou blessed,” the monument to Agnes Cromwell in Chichester Cathedral, which Flaxman himself called “one of my favourites” (illus. 1): its gently soaring rhythms are a deeply poetic expression of Christian faith.

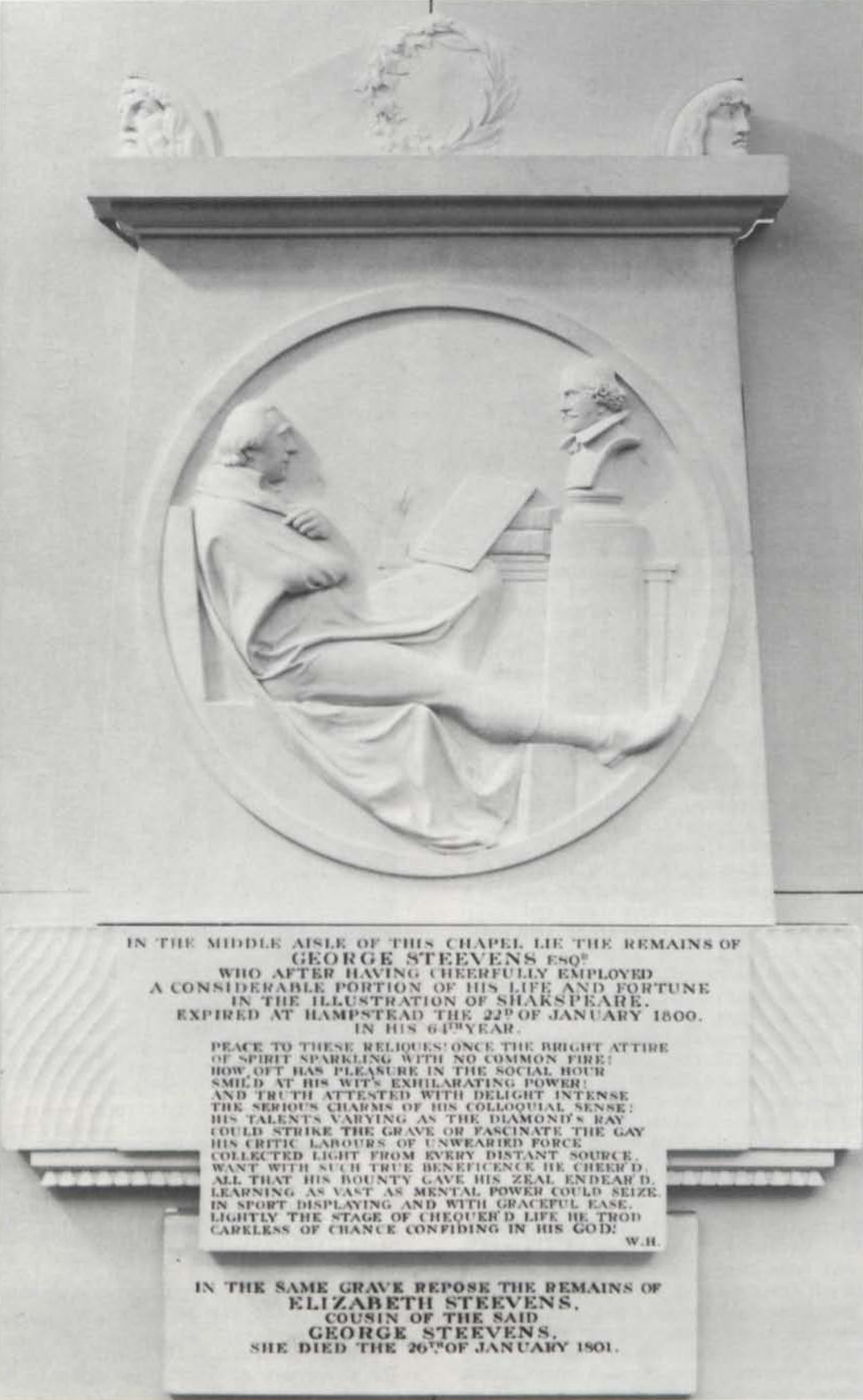

Inevitably (for one could hardly expect large-scale monuments to be dismantled from cathedrals for exhibition) only three finished works in marble were shown in the exhibition: the Royal Academy’s own charming bas-relief “Apollo and Marpessa” of c. 1790-94, later presented as Flaxman’s diploma work; the Thorvaldsen Museum’s strictly Neoclassical but (for Flaxman) almost sensuous bust of Henry Philip Hope, c. 1801-03, a sitter then in the prime of life; and the marble relief monument to George Steevens (d. 1800) from St. Matthias, Poplar, complete with William Hayley’s epitaph. In its attempt to echo the departed’s own attitude to life (“Lightly the stage of chequer’d life he trod”), the Steevens monument (illus. 2) was probably the most light-hearted work in the exhibition, though the nearest approximation to “light-hearted” allowed for it in the catalogue was “genial.” Few smiles occur in Flaxman’s work, as Hayley had already found when commissioning a medallion (not included in the exhibition) of his illegitimate son Tom: would it not be possible, he suggested, “to add a little gay juvenility to the features, without producing (what I by all means wish to avoid) a Grin or a Smirk?” But Flaxman was not in his profession to produce smiles, let along grins; even his domestic scenes are of affliction rather than bliss.

It is to Flaxman’s drawings, even more than to his sketch-models, that one must look for the most intimate expression of his ideas. Luckily, drawings ran like life-giving blood through almost the entire exhibition, revivifying images which had taken shape in other media and often revealing astonishingly inventive and imaginative powers. Paper thus became, in a very real sense, the most important material in the exhibition, though hardly the most colorful: most of Flaxman’s drawings are in pencil or pen and ink, sometimes with a wash—Flaxman’s work in full watercolor is extremely rare, and only one example (no. 152) was included. Flaxman’s early drawings revealed influences from Mortimer, Barry, Fuseli and Blake. They included the highly-finished self-portrait (illus. 3) and the remarkable study for begin page 27 | ↑ back to top

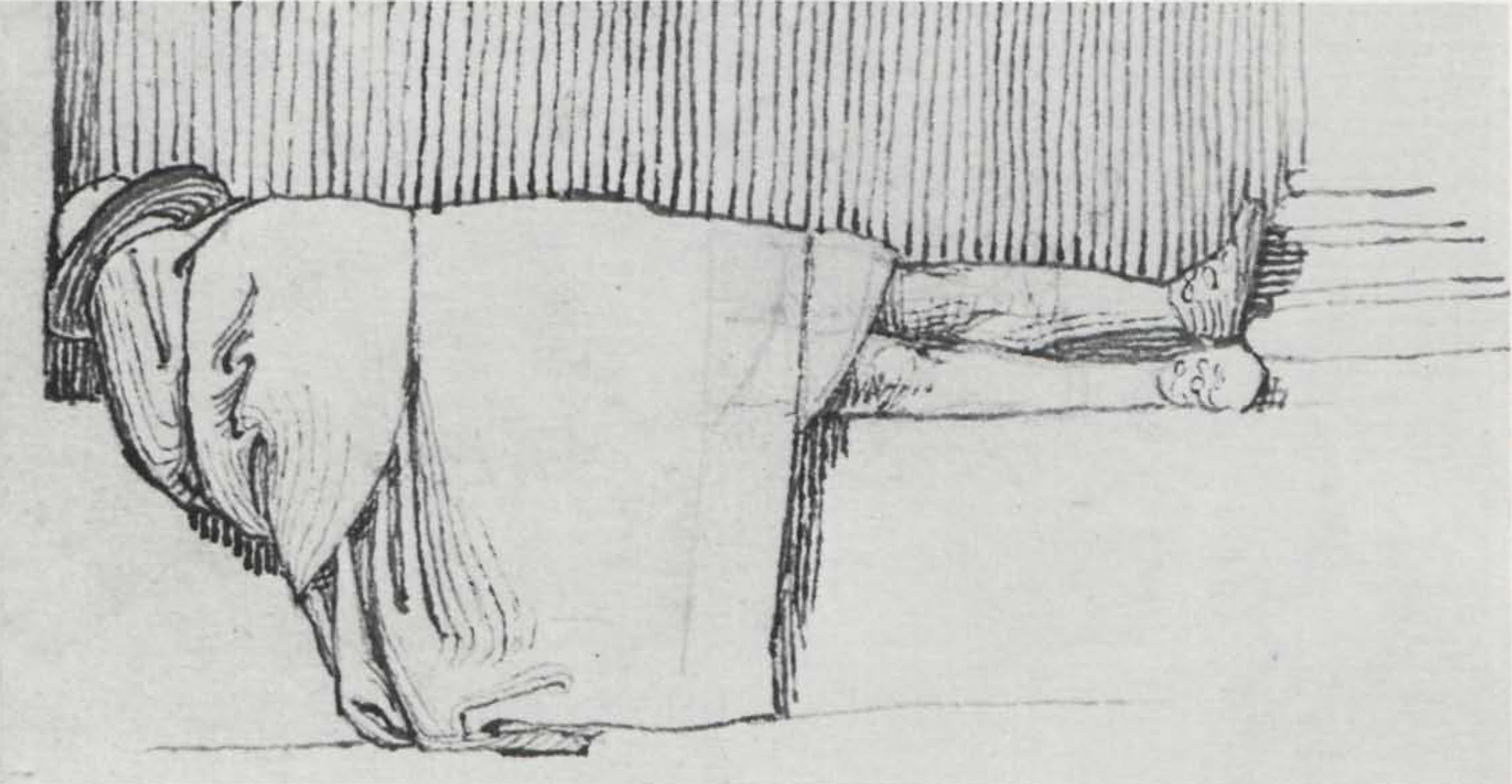

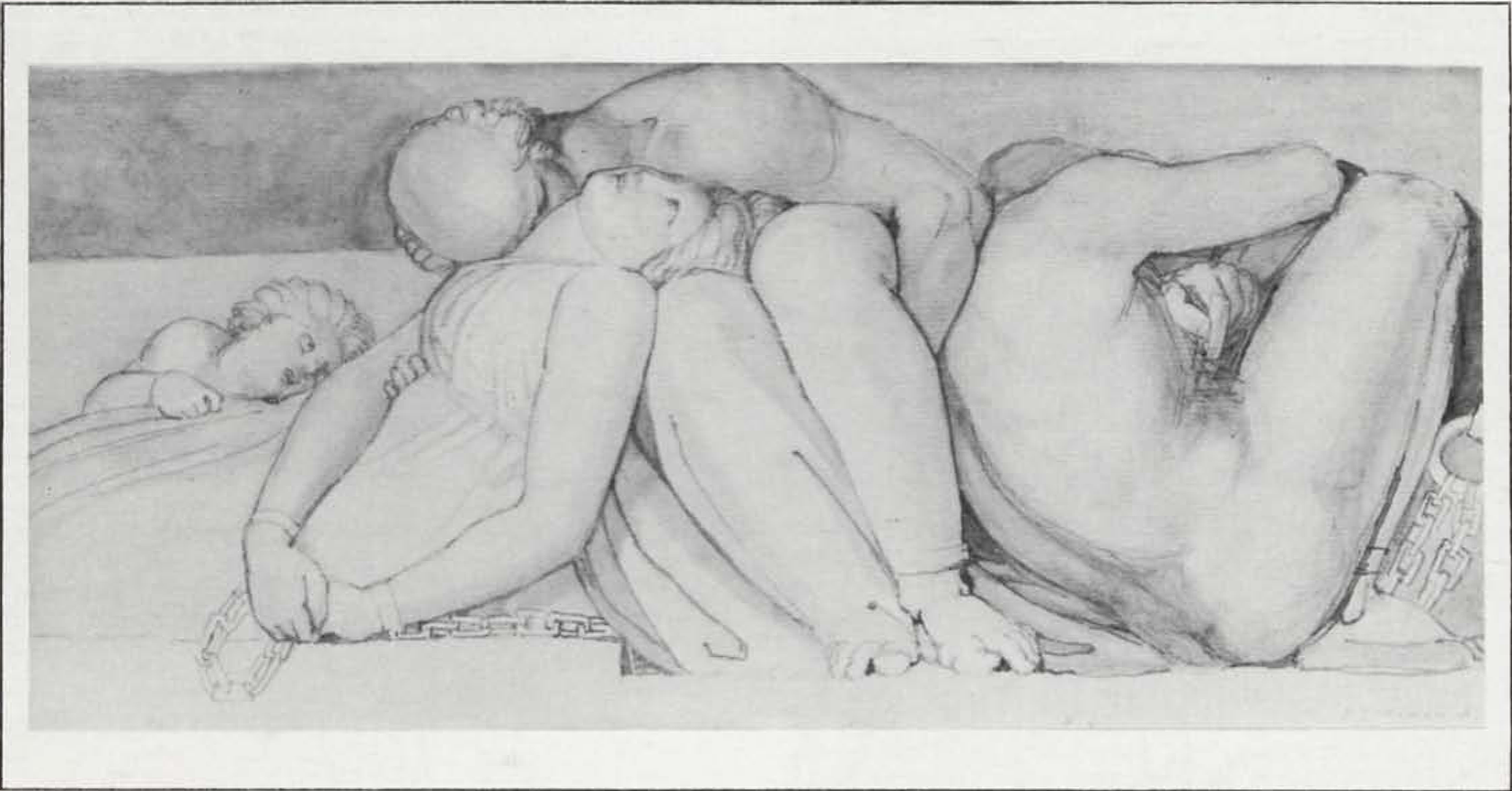

begin page 28 | ↑ back to top “Chatterton receiving a bowl of poison from Despair,” the high point of Flaxman’s youthful romantic style, in which Sarah Symmons (surely correctly) has detected Flaxman’s features in Chatterton’s face; they also included medieval subjects taken from such works as Percy’s Reliques, of the sort Blake too was painting at this time. Two early drawings by Blake, “Edward III and the Black Prince” and “The Death of Ezekiel’s Wife,” were included here for comparison. David Bindman, who provides perceptive commentaries on Flaxman’s drawings throughout the catalogue, points out that the early drawings have a poetic and atmospheric quality which Flaxman never regained after experiencing “the severity of the antique” in Rome.The Italian drawings of 1789-94 included the small but nobly-proportioned study of a woman and child (illus. 4) which proved capable of sustaining enlargement into an impeccable Neoclassical image for the Kunsthalle’s exhibition poster. (In choosing a poster to advertize the London showing, the Royal Academy’s exhibitions staff elected rather over-fulsomely to acknowledge generous support from the firm of Wedgwood: instead of the Kunsthalle’s powerful and appropriate design, Burlington House’s railings and London Transport’s walls displayed the chessmen designed by Flaxman for Wedgwood in 1785, Gothic “toys” magnified not only out of all proportion to their purpose but also to the relative importance in Flaxman’s long career of his work for Wedgwood.) The “Sleeping Man” (illus. 5) was described, fairly enough, as “one of the most spontaneous of Flaxman’s Roman life studies”: but few of Flaxman’s drawings, whether made in Rome or at any other time, were as directly observed as this. Observations from life may have kindled Flaxman’s imagination, but almost all his drawings are refined from life rather than studied directly from it, and almost all of them evince the sculptor’s instinct to model his subject-matter, to redesign, rearrange and interlock its shapes. The results can be exciting, even on the tiny scale of his studies of women and children; they can be deeply moving, as in the designs for “The Lord’s Prayer” and the “Acts of Mercy” (see illus. 6); but they are invariably deliberately generalized and potentially monumental.

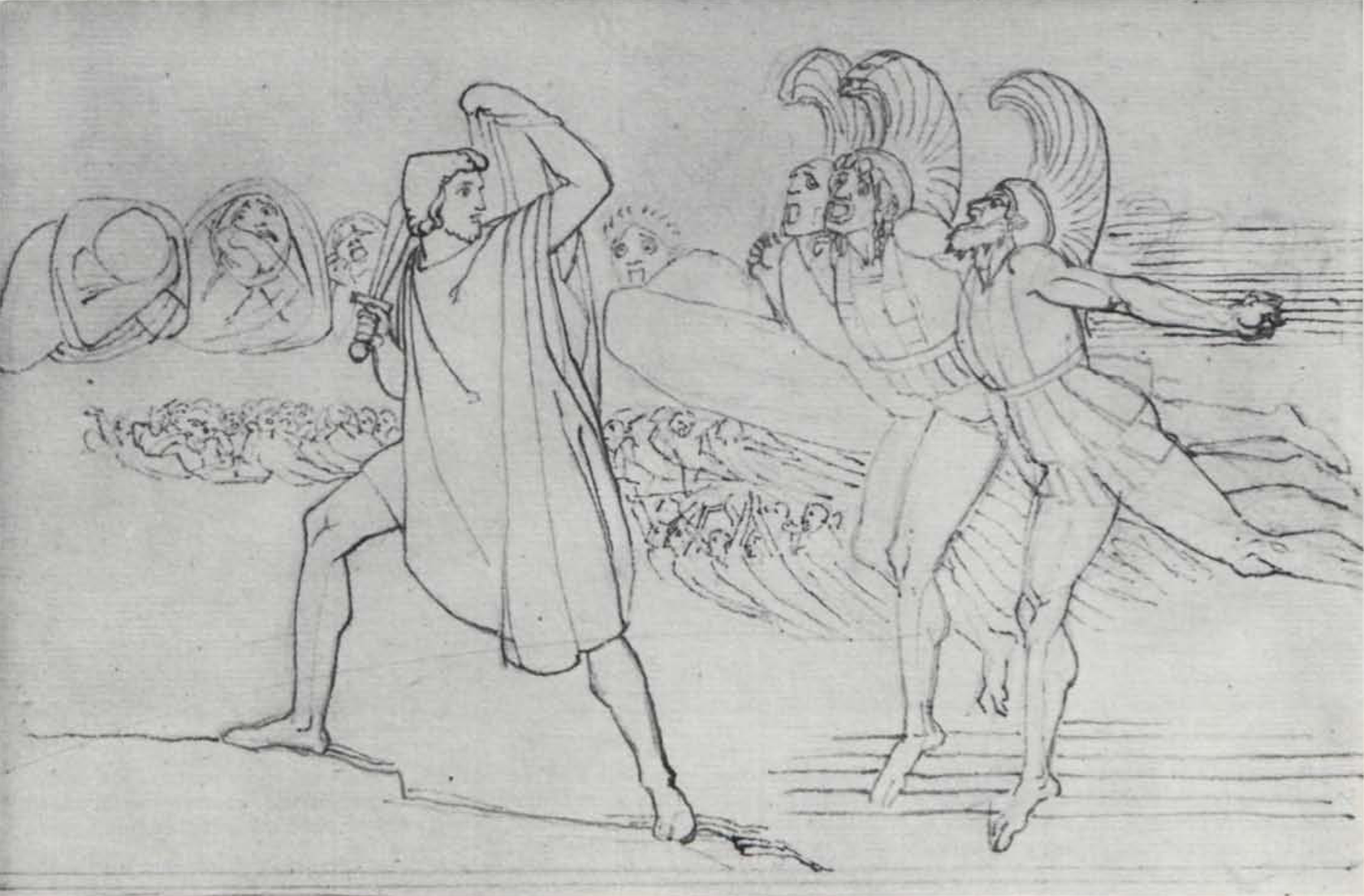

Flaxman himself stressed that the designs for which he was most celebrated in his own time, the outlines to Homer, Aeschylus and Dante, were primarily made as compositions on which sculptures could be based. He wrote to William Hayley on 26 October 1793 that “My view does not terminate in giving a few outlines to the world. My intention is to shew how any story may be represented in a series of compositions on principles of the Antients, of which, as soon as I return to England, I intend to give specimens in Sculpture of different kinds, in groups of basrelieves, suited to all the purposes of Sacred and Civil architecture.” Flaxman never in fact converted his outlines to sculpture; nevertheless, those outlines, engraved by Piroli and begin page 29 | ↑ back to top

first published by him in 1793, quickly secured Flaxman’s fame throughout Europe. The exhibition showed selections both of Flaxman’s drawings and Piroli’s engravings. The excitement felt throughout Europe on first looking into Flaxman’s outlines (especially in the form of Piroli’s rather genteel and monotonous line) is now difficult to recapture; but there is abundant evidence for the stimulus given to contemporary artists by these starkly dramatic sequences. “Cet ouvrage fera faire des tableaux,” David remarked. An important section of the exhibition (compiled by Sarah Symmons) illustrated the ways in which they provided inspiration for artists as different from each other as Ingres, Delacroix, Runge and Goya. Two works by Blake were included in this section, “The Hypocrites with Caiaphas” and “The Circle of the Lustful”; but it was decided to confine the coverage of Flaxman’s influence chiefly to the continent, as a separate exhibition devoted to Flaxman’s influence in England is projected. Perhaps the most bizarre suggestion for using Flaxman’s outlines was to come in 1863 from G. F. Watts, who suggested that they should be painted on the walls of public schools, so that “the young men of Eton would grow up under the influence of works of beauty of the highest excellence.”Any present-day jaded appetite for Flaxman’s outlines may be whetted by a delightful spin-off from the exhibition entitled Superflax: Zorrrrrrrn (Idee: Homer; Zeichnungen: John Flaxman; Buch und Regie: Achim Lipp; paperback, 25pp.). Published under the auspices of the Hamburger Kunsthalle, this presented Flaxman’s outlines to Homer as a lively adventure strip, taking a few liberties (such as reversing occasional details of the engravings to emphasize a clash of arms or the thundering of hooves) but recapturing much excitement. The witty (but not facetious) text was in German. The book was not available at the Royal Academy exhibition: should some enterprizing publisher essay an English edition?

A brief tabulated survey of the chief editions of engravings after Flaxman’s outlines published between 1793 and 1845 (pp. 184-5 of the exhibition catalogue) testifies to their wide circulation. Compiled by Detlef W. Dörrbecker,[e] with acknowledgments to Gerald E. Bentley Jr.’s study of 1964, it draws on further material kindly supplied by Professor Bentley from his new and greatly expanded edition of The Early Engravings of Flaxman’s Classical Designs, publication of which is expected shortly.

Flaxman’s outlines to Hesiod’s Theogony, begun in 1807, engraved by Blake in 37 stippled line engravings and published in 1817 (no. 155 in the exhibition) attracted little of the attention received by the outlines to Homer, Aeschylus and Dante. Blake at this period was undergoing a period of extreme neglect and poverty. Throughout his life he received none of the fame which accrued to Flaxman. This is not, after all, surprising. Flaxman gave his contemporaries what they (or at least connoisseurs among them) considered to be in the best possible taste, especially where commemoration of the dead was concerned. His vision of eternity did not extend beyond that of accepted Christian teaching; he was untouched by mysticism, and not temperamentally inclined towards exuberance. His morality was unimpeachable and, above all, it was readily intelligible. Blake’s work by contrast seemed to his contemporaries to be unconventional and worse, unintelligible; few of them bothered to discern that (in Dibdin’s phrase) Blake was “flapped by the wings of seraphs.”

begin page 30 | ↑ back to top