MINUTE PARTICULARS

BROMION’S “JEALOUS DOLPHINS”

The dolphin evidently never appears in Blake’s illuminations and only once in his verse, in a line spoken ironically by Bromion in Visions of the Daughters of Albion after he has “enjoyed” Oothoon: “And let the jealous dolphins sport around the lovely maid.”1↤ 1 William Blake’s Writings, ed. G. E. Bentley, Jr. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), I, 104. To understand some of its implications let us look briefly at the dolphin symbol and at some exhibits of the Galatea legend in music and art.

According to Oliver Goldsmith, “The dolphin was celebrated in the earliest time for its fondness to the human race . . . .”2↤ 2 Oliver Goldsmith, The History of the Earth, and Animated Nature (London, 1774), VI, 223. In classical legend the dolphin was a particular friend to man and often preserved a mortal from drowning, or at least wafted the body to shore for proper burial. The rescue of the musician Arion, for example, had been popularized by Theocritus and Ovid (Metamorphoses XIII.738, ff.) and had been taken over into emblem literature, most recently by Caesare Ripa’s English adapter George Richardson.3↤ 3 George Richardson, Iconology, or a Collection of Emblematical Figures (London, 1777-79), II, 67. In this extensive literature the dolphin became a symbol of safety and help in time of need.4↤ 4 Arthur Henkel and Albrecht Schöne, Handbuch zur Sinnbildkunst des XVI. und XVII. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1967), cols. 683-84. From its classical usage and its popularization as an emblem, it became a symbol popular also with the English poets. Both Spenser and Shakespeare referred to the Arion legend (FQ III.iv.33.1 and IV. xi.23.6; Amoretti, 38; Twelfth Night I.ii.15);5↤ 5 The Riverside Shakespeare, ed. G. Blakemore Evans (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974), p. 409. and Milton must have had this legend in mind, doubtless among others, when in “Lycidas” he entreated for the body of Edward King, “O ye Dolphins, waft the haples youth” (1. 164).6↤ 6 The Works of John Milton, ed. Frank Allen Patterson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1931-38), I, 82. Oothoon certainly needed dolphins to rescue her from the likes of Bromion and Theotormon.

But why are Bromion’s dolphins “jealous”? In addition to serving as symbols of safety and help, dolphins were also symbols of love. According to Goldsmith, the dolphin was distinguished by the epithet “the boy-loving” (VI, 223). Doubtless Goldsmith had in mind particularly the enamoured dolphin of Hippo whose love for a boy was related by Pliny the Younger in his Epistle IX. According to Ovid and Aulus Gellius, moreover, dolphins were reputed to be very amorous; and they were often depicted as attributes of Aphrodite or Eros. In his Metamorphoses Ovid related that Poseidon changed himself into a dolphin in order to woo Melantho (VI. 120); and according to Spenser, Hippomedes “turnd him selfe into a Dolphin fayre” (FQ III.xi.42.6) in order to win Deucalion’s daughter.7↤ 7 The Works of Edmund Spenser, ed. Edwin Greenlaw, Charles Grosvenor Osgood, Frederick Morgan Padelford, et al. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1932-49), III, 164. For the designs of Aphrodite or Eros on the dolphin see Nelson Glueck, Deities and Dolphins (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1965), pp. 31-35, and Eunice Stebbins Burr, The Dolphin in the Literature and Art of Greece and Rome (Menasha, Wis.: George Banta, 1929), pp. 83-84. Even more pertinent for Blake’s purpose, dolphins, according to Ovid (Fasti II.81-82), traditionally assisted lovers. According to legend, a dolphin had discovered the fleeing Amphitrite and had persuaded her to return to her lover, Poseidon; and the grateful sea god[e] had proclaimed the dolphin sacred and had set his image in the heavens in the constellation Delphinus.8↤ 8 Sir James George Frazer, Commentary, Ovid, Fasti, ed. Frazer (London: Macmillan, 1929), II, 304. Also, according to Erasmus, a dolphin “rescued the virgin Lesbia with her lover.”9↤ 9 Desiderius Erasmus, Adades, trans. Margaret Mann Phillips (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1964), p. 244. Moreover the dolphin has also symbolized spiritual salvation and Christ the savior.10↤ 10 See H. Leclercq, “Dauphin,” in Dictionnaire d’ Archéologie Chrétienne et de Liturgie, IV, cols. 283-95. The early Christians, for example, often employed the dolphin rather than the fish as a symbol for Christ; and at the Royal Academy Blake may have noticed this symbol as he looked over the treatises on the Roman catacombs. This emblematism might be an additional irony intended by the materialistic Bromion. At least it anticipates the spiritual salvation which Oothoon attains during the course of the poem.

But the dolphin-related legend which most closely fits the situation in Visions of the Daughters of Albion is that of the nymph Galatea and her lovers Acis and Polyphemos. When the Polyphemos-like Bromion speaks of “jealous dolphins,” he doubtless voices his own possessive view of love as well as that of the mute Theotormon; he attributes jealousy also to any potential rescuer. Though in the Galatea legend Polyphemos is yet to be blinded by Odysseus, he is already blinded by his jealousy, like the spiritually blind Bromion and Theotormon. Moreover, Bromion’s cave, in which we see the bound “adulterate pair” (4.2), may well echo the cave of Polyphemos. The dolphins rescue Galatea from her would-be rapist; they are ironically summoned too late to protect Oothoon. Yet in the final analysis the triumph of Oothoon even exceeds that of Galatea, who is likewise deprived of her lover. Both stories, moreover, are extended laments: as Galatea relates her tragic love story to Scylla and the other nymphs, so Oothoon relates hers to the daughters of Albion.

Blake and his contemporaries could have been familiar with the Galatea legend from its continued popularity in more than one medium. It was a favorite in English musical drama. It had been developed by John Lyly in 1592 in his Gallathea and revived twice in the eighteenth century, first by P. A. Motteux in 1701, with music by John Eccles, and next by John Gay in 1718-19, with lovely music by Handel. Since the Gay-Handel version was frequently performed from 1777 throughout the rest of the century, Blake could easily have seen a performance.11↤ 11 The London Stage, 1660-1800. Part V: 1776-1800, ed. Charles Beecher Hogan (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1968), III, 9 et passim. In February of 1786 even a ballet version was introduced, at the King’s Theater.12↤ 12 Ibid., II, 864.

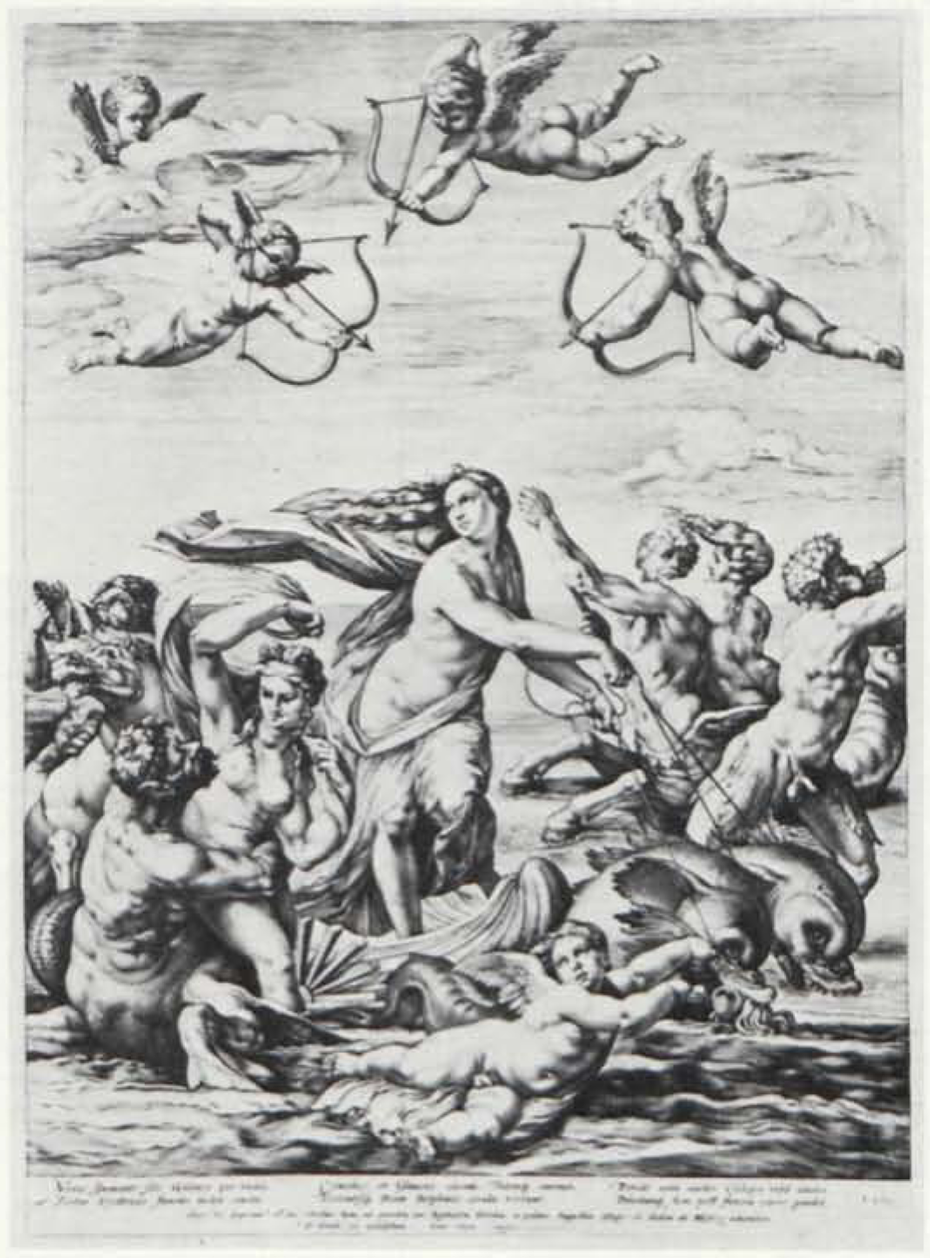

Blake was even more likely to have been familiar with the Acis and Galatea legend in art, especially the pictorial representation of “The Triumph of Galatea,” where the dolphins draw her and sport around the lovely maid as she escapes from Polyphemos and turns her lover Acis into a stream. Blake surely knew Raphael’s famous painting of this story, for Goltzius, among others, had engraved it.13↤ 13 Hendrick Goltzius, The Complete Engravings and Woodcuts, ed. Walter L. Strauss (New York: Abaris, 1977), II, 514. The story had also been depicted by many other artists whom Blake admired: Dürer, Giulio Romano, Nicolas Poussin, several of whose sketches were in Windsor Castle, and by Goltzius himself.14↤ 14 Andor Pigler, Barockthemen, eine Auswald von Verzeichnissen zur Ikonographie des 17 und 18 Jahrhunderts (Budapest: Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1956), I, 9-10; 85-87. In some of these versions Polyphemos sits disconsolately, like the jealous Theotormon, on a rock. In one of Poussin’s sketches he actually watches Galatea and Acis having sexual intercourse.15↤ 15 The Drawings of Nicolas Poussin, ed. Walter Friedlaender, Anthony Blunt, et al. (London: Warburg Institute, 1939-1974), Pt. iii, No. 160.

begin page 207 | ↑ back to topThe legend upon which Blake seems to have drawn helps us to focus attention on his theme—the tragic effects of jealousy. Though Blake was doubtless attacking physical as well as spiritual slavery, no hint of any negroid features seems to appear to characterize Oothoon or Theotormon in any of the plates. Their absence and the affinities in the Galatea legend which Bromion’s “jealous dolphins” evoke serve also to emphasize the major theme of possessiveness.