article

begin page 156 | ↑ back to topBLAKE’S JUPITER OLYMPIUS IN REES’ CYCLOPAEDIA

From 1804 until 1820 Blake worked on his illustrated epic poem Jerusalem. During those same years Abraham Rees, a learned divine, was in charge of compiling The Cyclopaedia; Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature.1↤ 1 London: Longmans, 1819. A major English encyclopedia was needed in “this period of illumination and general enquiry,” as Rees stated in the Prospectus directed “To the Public.”2↤ 2 “Dr. Rees’ New Cyclopaedia” (London, 1801). Copy courtesy of the University of Reading Library Archives. The thirty-nine volume Cyclopaedia was to surpass the Edinburgh-based Brittannica, which was in its ten-volume fifth edition.3↤ 3 Robert Collison, Encyclopedias (New York: Hafner, 1964), p. 141. As for the compendious work of the French Encyclopedists, the following notice from the “Domestic Occurrences” columns of Gentleman’s Magazine indicates the feelings of the encyclopaedia-buying public: “The Earl of Exeter expunged from his large and well-selected library, and burnt, the works of Voltaire, Rousseau, Bolingbroke, Raynal, and that grand arsenal of impiety, the French Encyclopedia.”4↤ 4 (August, 1798), LXVII, 718.

Rees was assisted in his worthy project for the edification of “intelligent and esteemed subscribers”5↤ 5 “Preface,” Cyclopaedia (London: Longmans, 1819), I, viii. by “EMINENT PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN” and “THE MOST DISTINGUISHED ARTISTS.”6↤ 6 Ibid., title page. The contributors were mainly Londoners, many of them drawn from the ranks of the Royal Academy and Royal Society and several of whom played significant roles in Blake’s life. Sir Humphrey Davy was called on to provide the articles on Chemistry. John Bonny-castle, a friend of Henry Fuseli, wrote some of the Astronomy sections. The musicologist, Sir Charles Burney, did not refrain from including a facsimile of a hand-written score from Rousseau—his counterpart for the Encyclopedie. Major Moor, whose illustrated Hindu Pantheon Blake was familiar with, wrote on Indian Mythology. Mr. Mushett was the authority on blast furnaces, yet he mentions not a word about the blacksmith Los. Benjamin Malkin, a friend and sometime employer of Blake, wrote a few of the biographical articles for which the Cyclopaedia was specially noted.7↤ 7 Alexander Gordon, “Rees, Abraham,” DNB (1896). The articles on painting were prepared by Thomas Phillips, who once had Blake sit for the portrait included in the illustrations to Blair’s The Grave. Blake’s old friend John Flaxman contributed articles on “Beauty,” “Basso Relievo,” “Armour,” and a book-length treatise on “Sculpture,” which was an extensive amplification of his “Lectures” at the Royal Academy. Among the engravers who made plates for the Cyclopaedia were Wilson Lowry, James Parker, Blake’s one-time business partner, and Robert Cromek, his nemesis in the publishing world.

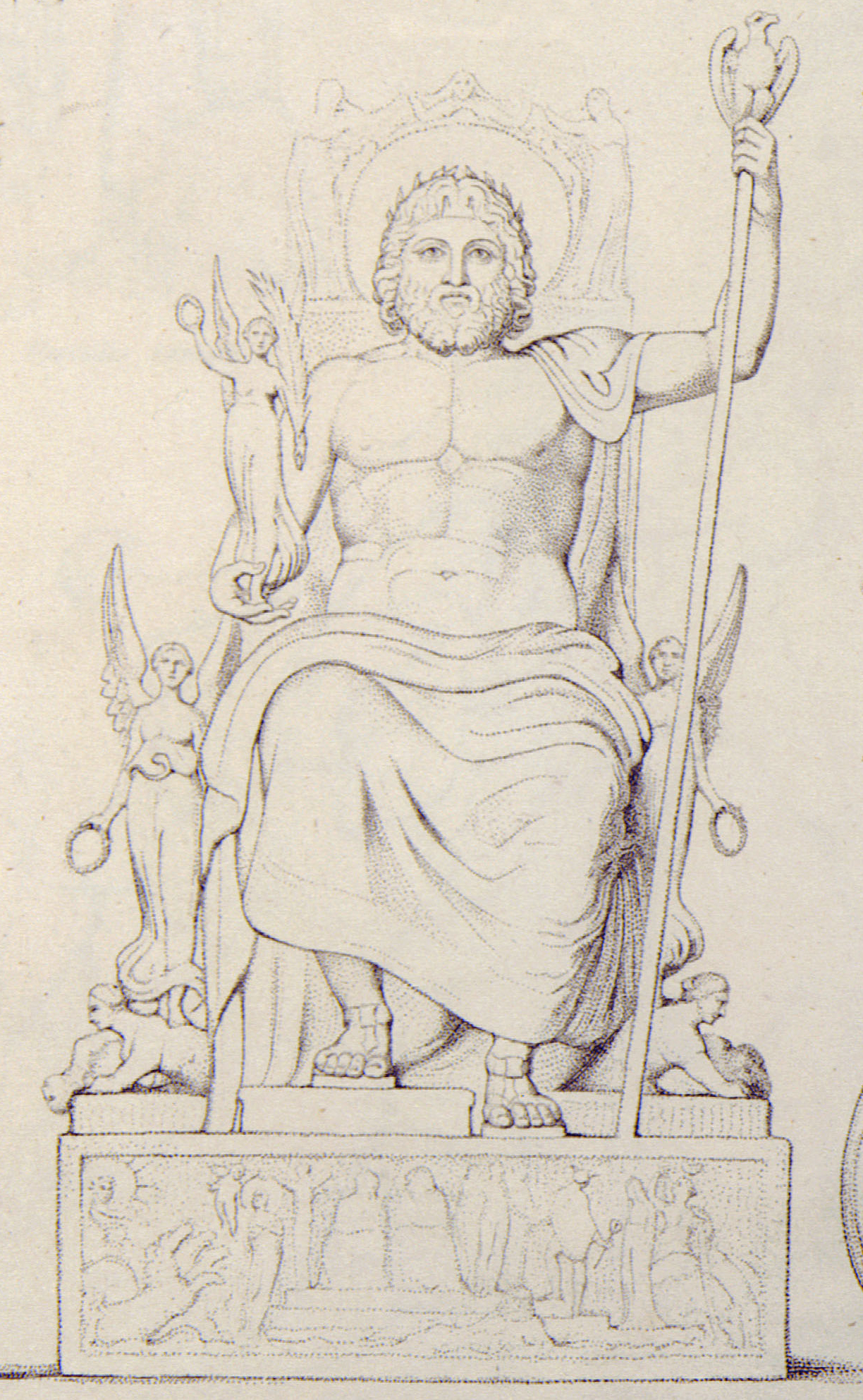

Blake himself was to join in the work on Rees’ Cyclopaedia with this “eminent” and “distinguished” company of men. At a time when Blake was living in poverty and obscurity, John Flaxman steered an occasional job his way. They were not always very satisfactory opportunities for one of the geniuses of the age, but engraving a “butter boat” for Josiah Wedgwood’s catalogue did out some food in the larder and porter on the table.8↤ 8 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 240. In 1815 Flaxman enlisted Blake to do the engravings for his “Sculpture” article, and also for “Armour,” “Basso Relievo,” and “Gem Engraving.”9↤ 9 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), #489. The four plates of the engravings for “Sculpture” include the old standards of Greek statuary: the Apollo Belvedere, the Medici Venus, the Knidian Aphrodite of Praxiteles, the Hercules Farnese, Jupiter Olympius the Athena Parthenos of Phidias, the Laocoön, and begin page 157 | ↑ back to top others (illus. 1). Also represented is a statue of Durga drawn from Moor’s Hindu Pantheon, an Etruscan Patera, a colossal statue at Thebes, a droll Chinese statue, and two examples of Persian sculpture from Persepolis. The plates in Rees are mere copywork, with perhaps one exception, the Jupiter Olympius, which stands out among the collection of gods, goddesses, and heroes. This stipple engraving of Jupiter is more concentrated, inventive, and minutely detailed than the rest, including the Laocoön which is certainly fainter by comparison.10↤ 10 The two most extensive treatments of Blake’s use of sculpture are to be found in Stephen Larrabee’s English Bards and Grecian Marbles (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943) pp. 99-119, and Morton Paley’s “‘Wonderful Originals’—Blake and Ancient Sculpture” in Blake in His Time, ed. Robert Essick and Donald Pearce (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978), pp. 170-97.

Before treating Blake’s representation of the Jupiter Olympius, some background on the statue itself and its place in the history of art will provide a context for Blake’s work. Phidias’ statue of Zeus in the Temple at Elis, the site of the Olympic games, was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Strabo reports that when asked “after what model he was going to make the likeness of Zeus, [Phidias] replied that he was going to make it after the likeness set forth by Homer in these words: ‘Cronion spake, and nodded assent with dark brows, and then the ambrosial locks flowed streaming from the lord’s immortal head, and he caused great Olympus to quake’ (Iliad I. 528)” (Geography viii. 3.30). John Flaxman describes the statue this way in his Lectures: ↤ 11 The account is based on Pausanias’ Description of Greece (v. 11.1-9). John Flaxman, Lectures on Sculpture (London, 1838), pp. 89-90.

But the great work of this chief of sculptors, the astonishment and praise of after ages, was the Jupiter at Elis, sitting on his throne, his left hand holding a scepter, his right extending victory to the Olympian conquerors, his head crowned with olive, and his pallium decorated with birds, beasts, and flowers. The four corners of the throne were dancing victories, each supported by a sphinx, tearing a Theban youth. At the back of the throne, above his head, were the three hours or seasons on one side, and on the other the three graces. On the bar between the legs of the throne, and the panels or spaces between them were represented many stories. . . . On the base the battle of Theseus with the Amazons; on the pedestal, an assembly of the gods, the sun and moon in their cars, and the birth of Venus. The height of the work was sixty feet. The statue was ivory, enriched with the radiance of golden ornaments and precious stones.11 (illus. 2)

Prodigies were associated with the statue from the beginning. In his Description of Greece, Pausanias relates “that the god himself evinced his approbation of the art of Phidias; for, as soon as the statue was finished, Phidias prayed to Jupiter, and entreated him to signify if the work was pleasing to his divinity; and immediately after he prayed, they say, that part of the pavement was struck by

begin page 158 | ↑ back to top lightning.”12↤ 12 Pausanias, The Description of Greece, trans. Thomas Taylor (London, 1824), I, 29. Martin Robertson notes that “the floor in front was paved with black marble and there was a reflecting pool of oil that not only served to preserve the ivory but to cast light up on and reflect the figure.”13↤ 13 A History of Greek Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), I, 317. The seated figure filled the space, his lofty head almost touching the ceiling. Imagine the effect on a suppliant when the towering statue doubled in an eerie light! The effect was to induce a state of religious awe attested to by Dio Chrysostom, for one:O best and noblest of artists, how charming and pleasing a spectacle[e] you have wrought, and a vision of infinite delight for the benefit of all men, both Greeks and barbarians, who have ever come here, as they have come in great throngs and time after time, no one will gainsay . . . . Whoever is sore distressed in soul, having in the course of his life drained the cup of many misfortunes and griefs, nor ever winning sweet sleep—even this man, methinks, if he stood before this image, would forget all the terrors and hardships that fall to our human lot. Such a wondrous vision did you devise and fashion, one in very truth a

“Charmer of grief and anger, that from men All the remembrance of their ills could loose!”

So great the radiance and so great the charm with which your art has clothed it.

(Discourses XII; 51-52)

The statue itself had a curious history. For six centuries it remained at Elis, revered by Greeks, Romans, and barbarians alike, such was its universal power. Caligula attempted to have the statue carried off to Rome to adorn the imperial city, but Suetonius reports that the statue “suddenly uttered such a peal of laughter that the scaffoldings collapsed and the workmen took to their heels” (The Lives of the Caesars, IV, 57). The Emperor Theodosius was more successful in plundering the temple. In 373 A. D. he abolished the Olympic Games and profaned the temple of Zeus when he had the chryselephantine statue expropriated to New Rome (Constantinople).14↤ 14 Enno Fraxius, A History of the Byzantine Empire (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1967), p. 43. There it joined in captivity the Knidian Aphrodite of Praxiteles, the Eros of Mindos by Lysippus, and many other masterpieces by Greek artists. A quote from Blake’s “On Virgil” makes apt comment here: “A war-like State never can produce Art. It will Rob & Plunder & accumulate into one place & Translate & Copy & Buy & Sell & Criticise, but not Make.”15↤ 15 Blake: Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (London: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 798. Subsequent references to this edition appear in the text. The fire at the library of Alexandria was one of the seven catastrophes of the ancient world; another was the great fire at Constantinople in 475, which destroyed the Palace of Lausos. Thousands of works of art were irrevocably lost in the disaster, including the Zeus and other works by Phidias, Praxiteles, and Lysippus.16↤ 16 Georgius Cedrenus, Historiarun Compendium, 322C, Vol. I, p. 564 (Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae, Vol. 34). No detailed copies of the Zeus remained, though dim one-dimensional likenesses on coins and some gem engravings do survive.17↤ 17 See G. M. A. Richter, The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1970), figs. 647-53.

In Blake’s era Phidias and his Olympian Zeus were highly esteemed. Winckelmann in his Reflexions on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, translated by Fuseli, gives the highest place to Phidias: “The Zeus of Phidias was the standard of sublimity, the symbol of the omnipresent Deity, like Homer’s Eris, he stood upon the earth, and reached heaven.”18↤ 18 (London, 1765), p. 148. In Joseph Spence’s Polymetis (1747) is this passage on the Jupiter: “The superiority of Jupiter . . . was in that air of majesty which the ancient artists endeavoured to express in his countenance. If some of the nobler statues of Jupiter, as that of Jupiter Olympus made by Phidias, in particular, had remained to our times; we might see this more strongly at present; for that was reckoned the master-piece of the greatest statuary that ever was; and those who beheld it are said to have been astonished at the greatness of ideas in it.”19↤ 19 Spence, p. 51. The desire to have had a glimpse of the original is clear.

Though Blake took exception to the uninspired opinions of his patron William Hayley, he would not have quarreled with the gentleman’s estimation of Phidias. Hayley had finished his Essay on Sculpture just before Blake came to work for him in 1800. In lock-step heroic couplets he describes how he is taken “in vision” to see the Zeus; then he addressed Phidias: ↤ 20 Hayley, p. 55.

All vouch thy fame, though not in speech—Blake himself thought Phidias ranked with Homer and Socrates (Anno Watson, K 388).

Thine, the prime glory pagan minds could reach—

Thine, to have form’d, in superstition’s hour,

The noblest semblance of celestial power!20

In 1800 John Flaxman was the “Happy son of the immortal Phidias” to Blake (Letters, K 807). Flaxman’s thoughts on his spiritual father are giver in the “Sculpture” article in Rees’ Cyclopaedia: “Superior genius, in addition to a knowledge of painting, which he practiced before sculpture, gave a grandeur to his compositions, a grace to his groups, a softness to flesh, and a flow to draperies, unknown to his predecessors . . . . The discourse of contemporary philosophers on mental and personal perfection assisted him in selecting and combining ideas, which stamped his work with the sublime and beautiful of Homer’s verse. . . . The great work of the great master, the astonishment and praise of after ages, was the Jupiter at Elis.”21↤ 21 Abraham Rees, Cyclopaedia (London: Longmans, 1819), XXXII, not paginated. From ancient commentary to Blake’s own friends the preeminence and power of Phidias were celebrated, and in 1815 Blake got the chance to turn praise into a picture.

The Olympian Jupiter was one of the statues to be engraved for the Sculpture plates in Rees’ Cyclopaedia. Blake engraved the plate, but it is not entirely clear whether it was Blake, Flaxman, or the two together who worked out the design of the picture. Spence outlines the problem facing the artist: “It is a great pity that we have no better figures of Jupiter . . . they fall short even of the idea one can form of a Jupiter in one’s own mind, by the help of ancient poets, and infinitely short of the celebrated Jupiter made by Phidias.”22↤ 22 Spence, p. 46. Here was a chance to create a likeness of Jupiter and in a way “to renew the lost Art of the Greeks,” a one-time ambition of Blake (Letters, K 792).

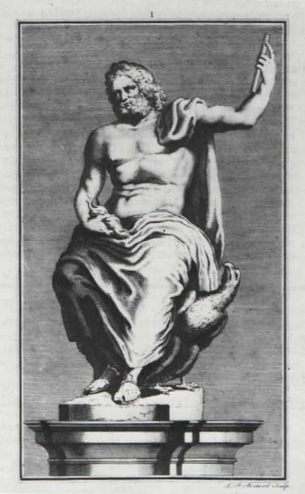

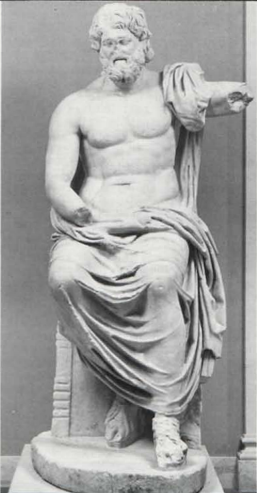

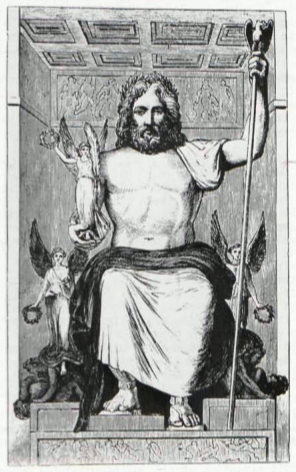

begin page 159 | ↑ back to topIn addition to the imaginative powers of the designer, there were other sources for the engraving: traditional representations of Jupiter, the Hellenistic statue of Jupiter in Marbury Hall, and a literary description in the writings of Pausanias. The engraving in the Polymetis exemplifies the standard iconography associated with Jupiter (illus. 3). In the Marbury Hall Zeus we have a likely model for the basic attitudes of the Jupiter in Rees (illus 4). The torso, beard, and especially the pallium are similar, though the body is more symmetrically arranged in Blake.

For the fine detail in the engraving, we are directed to “See Pausanias,” whose Description of Greece contains a minutely detailed verbal portrait of the famed statue. The engraving follows almost verbatim the description, of which Flaxman quotes the relevant sections in his Sculpture article. In giving Pausanias’ account I have added a [Y]-yes- and an [N]-no-to indicate whether the engraving follows the description. As the picture is black and white/two-dimensional, some qualities of the sculpture do not apply: “The god is seated upon his throne [Y], made of gold and ivory, a crown of olive branch on his head [Y], in his right hand bearing a Victory [Y], also of ivory and gold; she bears a fillet, and is crowned [Y-but the olive crown is in her right hand]; the left hand of the

god holds a sceptre of various coloured metals [Y]; an eagle of gold sitting upon the sceptre [Y]; his garment is of gold, and on his garment are wrought animals and flowers, particularly the lily [N23↤ 23 This detail is followed in Flaxman’s designs to the Iliad, (London, 1805), plate 5. ]; his sandals are of gold; the throne is variously ornamented with gold and gems, and also ivory and ebony: on it animals are painted in their proper colours, and sculptured with great labour [These pictures on the sides and back of the work are not shown in the frontal view of the engraving]. Four victories, as in the dance, are on the hinder feet on the throne, two on each side [Y-two of the four are brought forward]; and on the front the children of the Thebans taken away by the sphynx [Y] . . . . [Pausanias goes on to describe numerous scenes that surround the statue but are not included in the engraving]. Upon the throne, above the head of the god, Phidias carved the Graces and the Hours [Y]. begin page 160 | ↑ back to top Three of them large; these are called daughters of Jove. [Three of these Graces form the outer ring of the halo-arch over Jupiter’s head. Two, though there should be three, cherubs make the inner ring].” It is evident that the engraving is based on this description, but as to the character and expression of the Jupiter there is more to say.A quote from Homer that Phidias did not note as a source of his inspiration still felicitously describes this Jupiter: “He, whose all-conscious Eyes the World behold, / Th’ Eternal Thunderer, sate thron’d in Gold” (Iliad VIII, 550-51).24↤ 24 Alexander Pope’s translation. The face radiates omniscience and the symmetrical features indicate harmony. The heroic torso, firmly-set feet, and symbols of power all combine to picture majesty of character. Even the beard contributes to the effect. Spence comments on this point: “What is nobler than the long beard in Michaelangelo’s Moses? A full beard surely may give majesty as well as a long one, and you see, in effect, how much it gives . . . . to the heads of the Greek Jupiters . . . . A full beard still carries the idea of majesty with it, all over the East; which it may possibly have had ever since the times of the patriarchal government there. The Grecians had a share of the oriental notion of it.”25↤ 25 Spence, p. 52. Power inhabits the Jupiter from the head, with its flame-like laurel wreath, to the feet where the redoubtable Sphinxes are stationed like obedient guards.

Still there is not much sign of the wrathful, terrible thunderer in this picture. Spence explains how the benevolent aspect befits this deity: ↤ 26 Ibid.

Among the different characters of Jupiter, I think I have mentioned to you those of the Mild and of the Terrible Jupiter . . . Mild Jupiter’s face has a mixture of dignity and ease in it. That serene and sweeter kind of majesty . . . The statues of the Terrible Jupiter were represented in every particular differently from those of the Mild Jupiters. These were generally of black marble, as those were of white. The one is sitting with an air of tranquility; the other, is standing and more or less disturbed. The face of one, is pacific and serene; of the other angry or clouded. On the heads of one, the hair is regular and composed; in the other, it is so discomposed that it falls half-way down the forehead.26begin page 161 | ↑ back to top The “Terrible Jupiters” have distant cousins in the truculent demons that guard the gates of many Hindu and Buddhist temples; but in this engraving we are certainly presented with a “Mild Jupiter.”

The combination of strength and benevolence evident in the statue is further explicated from the glosses of Thomas Taylor: “‘Jupiter is seen holding a sceptre, and [winged] victory.’ Jupiter is every where called by Homer . . . ‘the father of gods and men, ruler and king, and the supreme of rulers . . . ’ On account, therefore, of his commanding or ruling characteristic, he is very properly represented with a sceptre, which is certainly an obvious symbol of command. The symbol of victory likewise justly belongs to him, on account of his all-subduing power, which vanquishes all mundane opposition, and causes the war of the universe to terminate in peace.”27↤ 27 In the commentary to Pausanias, III, 193. Hayley declaimed the virtues of the peace-bestower in his Essay on Sculpture: ↤ 28 Hayley, p. 53.

Lo, in calm pomp, with Art’s profusion bright

Whose blended glories fascinate the sight,

Sits the dread power! Around his awful head

The sacred foliage of the olive spread,

Declares that in his sovereign mind alone

Peace ever shines, and has forever shone.28

The divine nature of the subject is emphasized by the arrangement of Graces and Seasons about Jupiter’s head. The halo-effect of the attending Graces and Seasons is not accounted for in Pausanias; in fact he mentions that they are disposed to the right and left of Jupiter’s head. Haloes around the heads of pagan gods are found elsewhere in eighteenth and nineteenth century art,29↤ 29 Flaxman’s Iliad, plate 9, and Odyssey, plate 1, are two examples, the styles of which contrast with the halo in Rees. but the effect in this picture certainly contributes to the portrayal of Jupiter as a Prince of Peace. This Jupiter is neither a despotic Greek god nor a tyrannical Urizen. Blake himself says forthrightly: “Consider that the Venus, the Minerva, the Jupiter, the Apollo . . . are all of them representations of spiritual existences, of Gods immortal to the mortal perishing organ of sight; and yet they are embodied and organized in solid marble” (Descriptive Catalogue, K 576). A representation of celestial power has here been embodied and organized in dots of ink.

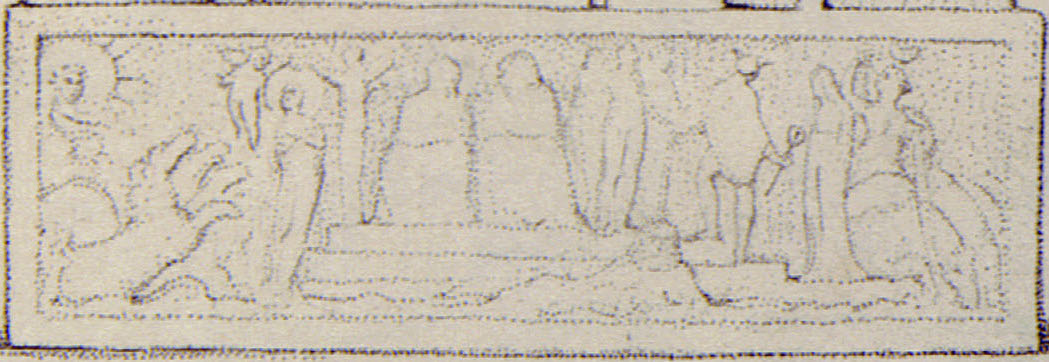

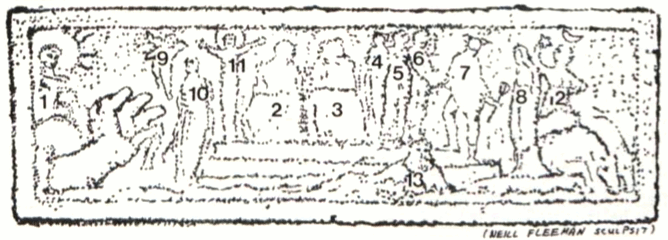

On the base of the Jupiter statue is a picture of a bas-relief in such minute detail as to call for a magnifying glass (illus. 5). The Lilliputian beings outlined in dots are a company of Olympian gods that appear more the size of fairies. Once again the artist has stayed close to the description in Pausanias, which allows us to identify the characters: “Upon the base of the throne, which great mass was wrought in gold, are other ornaments relating

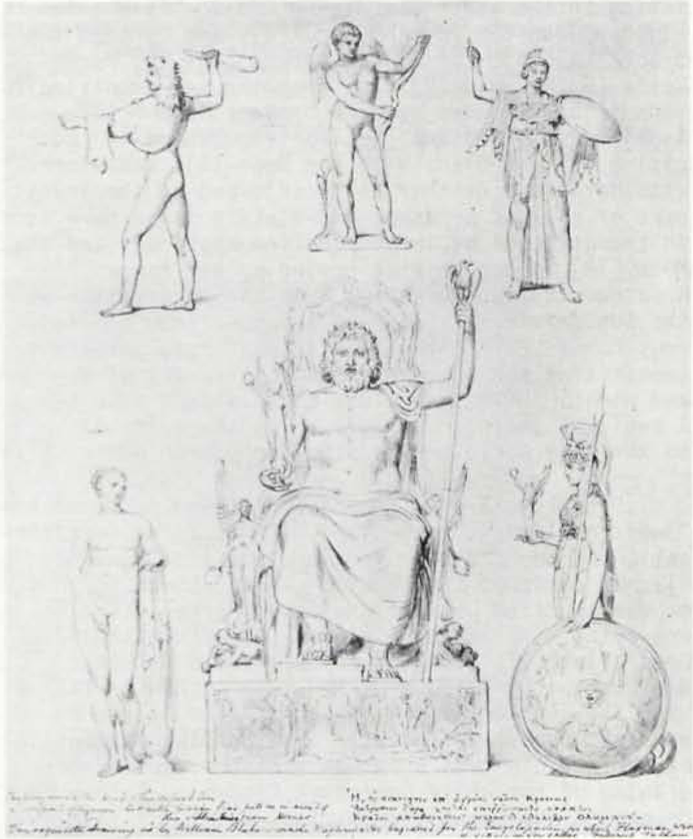

Finally there is the matter of who designed the “Jupiter Olympius” engraving. There is no identification of the designer on the plate itself. When Flaxman designed the “Basso Relievo” plate in 1804, he was credited with it and James Parker with the engraving. “Blake del[iniavit] et sc[ulpsit],” in Rees’ Plate III with the Laocoön tells us Blake drew the picture and engraved it. On Rees’ Plate I with the Jupiter simply appears “Blake sc.” He engraved the plate, but the designer is not mentioned. Blake did make a rather finished preliminary drawing of the whole page that Frederick Tatham described as “exquisite” (illus. 6).31↤ 31 With the Greek quotation translated, the text in Tatham’s hand reads: “The Glory round the Head of this superb Jove is composed of figures. That noble God-like head puts us in mind of these sublime lines from Homer. ‘Cronion spake and nodded assent with dark brows, and then the ambrosial locks flowed streaming from the lord’s immortal head, and he caused great Olympus to quake’ [Iliad I.528]. This exquisite Drawing is by William Blake-made & afterwards Engraved for the Encyclopaedia for which Flaxman wrote the article on Sculpture. Frederick Tatham.” In Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1981), this drawing is 678A recto, pl. 896A; the verso is reproduced as pl. 897. Blake’s drawing of the page is not conclusive proof that he designed it, for he may have been working from a prior drawing by Flaxman. Still, the existence of the drawing makes it likely that he had a hand in the design, and two differences between the drawing and the final engraving itself make it even more likely: (1) In the bas-relief on the base Neptune is moved from the left foreground to the right. (2) The Moon-goddess is moved closer to Vesta and her right arm is raised. Blake probably made these changes as he understood the need to balance the groupings more effectively.

If a design was provided it would most probably have been by Flaxman. When his Lectures were published in 1838, sculpture[e] plates from his drawings were included. While there is a basic similarity in the two engravings of Jupiter, Flaxman’s picture of “Jupiter Olympus at Elis” (illus. 7) differs markedly from the Rees Jupiter: (1) The expression of the face and drawing of hair and beard are clearly different. (2) The eagle, sphinxes, and victims are more detailed. (3) There is no halo effect of Graces and Seasons. (4) The statue is placed in a temple setting with roof and walls. (5) The design of the bas-relief differs by being quite vague, and the Moon is driving a chariot pulled by two active horses. while Flaxman could have done another drawing, this Flaxman design was not the basis of the Rees engraving.

The mild Jupiter that dwells in the dusty precincts of an outmoded household encyclopaedia reveals many elements of Greek religion and thought. Although Blake’s attitude towards the Greeks shifted from admiration to distrust between 1800 and 1815, his deft execution of the Jupiter Olympius engraving belies a dogmatic dismissal of Greek tradition. This miniature colossus invites contemplation by any who would like a glimpse of one of the sculptural wonders of the Golden Age.