REVIEWS

David V. Erdman ed. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press; and Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, Doubleday; 1982. xxvi + 990 pp. $29.95, cloth and $19.95, paper.

The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David Erdman, arrives as a “Newly Revised Edition” to replace and “complete” (principally by the inclusion of all the letters) the editor’s earlier effort, The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, now out of print after selling over 38,000 copies.1↤ 1 The hardcover edition was first published in 1965 and had sold 6,913 copies by 1972; the paperback was introduced in 1970, and in its most successful year (1974) it sold just under 4,000 copies. The Illuminated Blake, by contrast, has sold only about 15,000 copies in all, with fewer than 1,000 of these in hardcover, since it was published in 1974. We are grateful to Mr. David Gernett of Anchor Press, Doubleday & Co., for supplying these figures. The initial University of California Press printing of 1,500 copies sold out within a year, leading to a second printing of 1,000 copies and a list price of $38.50. 2,800 additional copies were printed with the first run for a subscription book club. Our thanks to Ms. Anne Ebers, University of California Press, for this information. The old E, as it was usually cited, quickly became the generally recognized authoritative text for Blake’s work. The new E, as it will be cited here,2↤ 2 In “Redefining the Texts of Blake (another temporary report)” David Erdman announces that “ ‘C’ has been chosen as symbol for the new edition (rather than, say, E2) as more impersonal and in recognition of the committees of textual scholars who watched and assisted the labor . . . ” We prefer at least for the time being, for the purposes of this review/essay, to refer to the new E simply as E, specifying “old E” where necessary to avoid confusion. There are indeed pertinent consonantal alliterations that support the Choice of “C” as symbol. It is a Collective enterprise (though we note the Copyright is David V. Erdman, 1965, 1981). It Claims to be the Complete Poetry and Prose, and it has been approved by the Committee on Scholarly Editions which is Chaired by Don Cook who announces that “We are particularly pleased to have been able to Co-operate in this wedding of scholarly and practical publishing” (E VI). There may also be suggestions of Correctness and Certainty and Canonical for “a volume that can be expected to receive immediate acceptance both as a standard scholarly edition and a Classroom text” (E VI). But whose Expectations are these? And is it not possible that “C” is a (small) part of the machinery that may enable those expectations to become self-fulfilling? It may be fanciful to imagine that adopting “C” too readily would have any Consequences at all; but the tactical effect of a new Edition with its powerful Claims are potentially vast, not the least of which may be drastically to alter the “value” of the many thousands of Copies of and citations to the old E still in use and circulation. Is the new E in fact so much changed and so much more authoritative that scholars who claim to be reputable will now have to make the switch and require their students to do the same? Has the “text” Changed, even where the wording is the same, by having been more authoritatively Certified? How substantial are the changes? Will those readers who continue to use the old E be in Error? Will scholars who cite it be Errant? Must E go the way of K, and must B Continue to remain in left field? We prefer to keep the designation “E,” suggesting not only Erdman, but Editing and Editor and Edition, which will be the focus of much of our discussion. adds to this impressive mantle of approval two more layers of certification. First, thanks to a transfer of the hardcover rights by Anchor/Doubleday, a University Press now publishes the library copies. The new E’s second nil obstat appears in the form of an actual “emblem” gracing the back of the dust jacket, signifying that this volume is approved and sanctioned by the Modern Language Association Committee on Scholarly Editions, known as the MLACSE (illus. 1). The distinction conferred by award of this emblem of approval raises a number of questions that make a review of this volume more than an ordinary enterprise.

Is this new revised standard edition now officially authorized as the one which should be purchased and read in the sizable academic market? Has the MLACSE presumed to make definitive the long-standing distinction between Blake’s verbal and his visual artistic components?3↤ 3 The new E, like the old E, has four illustrations and eight figures, along with the seventeen emblems for The Gates of Paradise (G. E. Bentley, Jr. William Blake’s Writings [2 vols.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1978], by contrast, offers three hundred and eleven illustrations). Does the MLACSE emblem of approval extend to the distinctly not “newly revised” commentary by Harold Bloom still included? In what follows we shall examine a few minute particulars of this edited version of Blake’s “text” bound back-to-back with the “Commentary” in this volume. But our main concern shall be to raise some theoretical questions about the assumptions and presuppositions that inform the editorial enterprise which made the production and institutional approval of this volume possible.

I. MINUTE PARTICULARS

The Ancients entrusted their [ ] to their Editors

Now then, after four hundred years, the truth of the law comes forth to us; it has been bought for money in the synagogue. When the world is grown old and everything hastens to the end let us even put it on the tombs of our ancestors, so that it may be known to them too, who read a different version, that Jonah did not have the shadow of a gourd but of an ivy; and again, when it so pleases the legislator, not an ivy but some other bush. (Rufinus, Apologia contra Hieronymum)

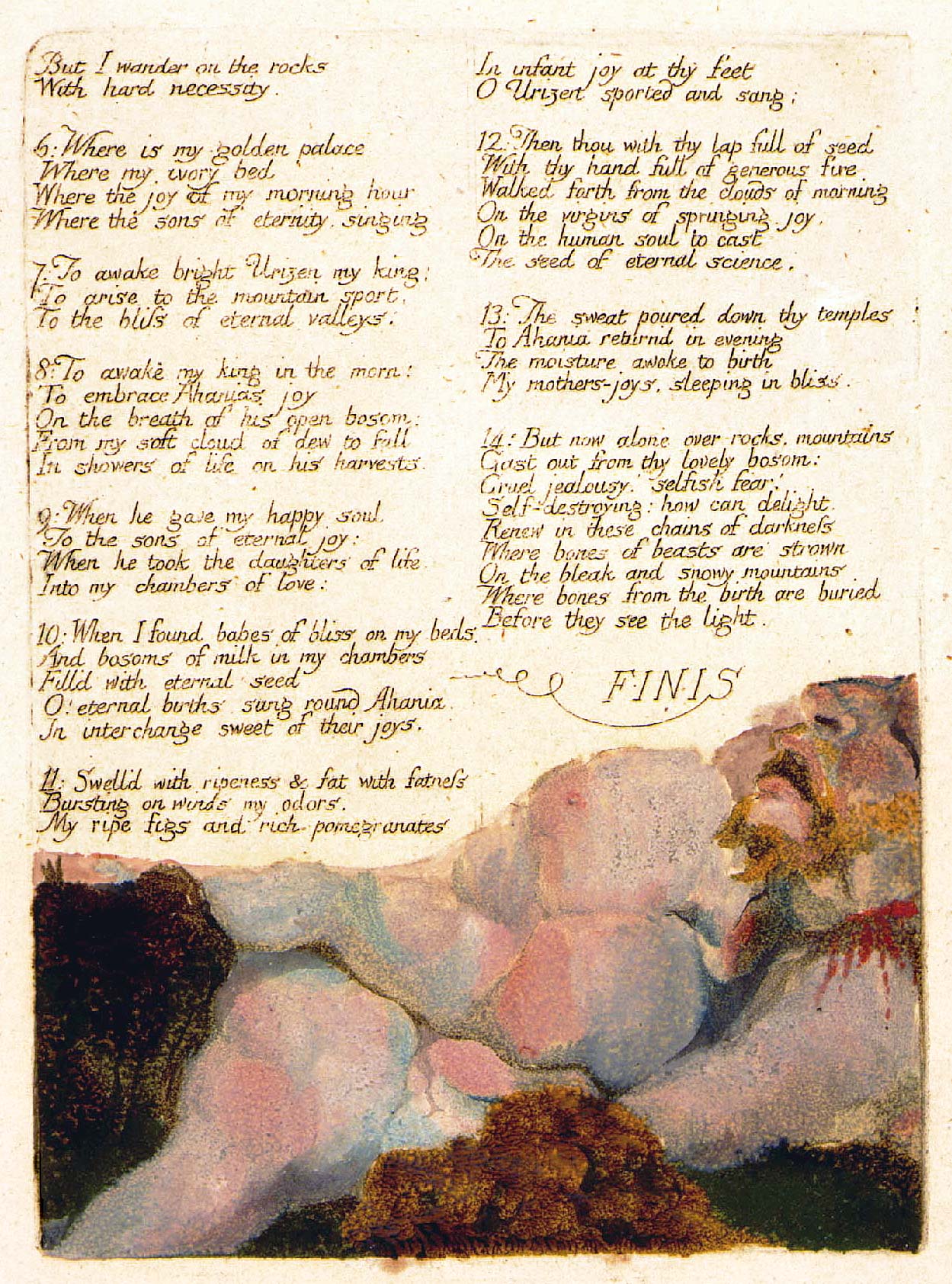

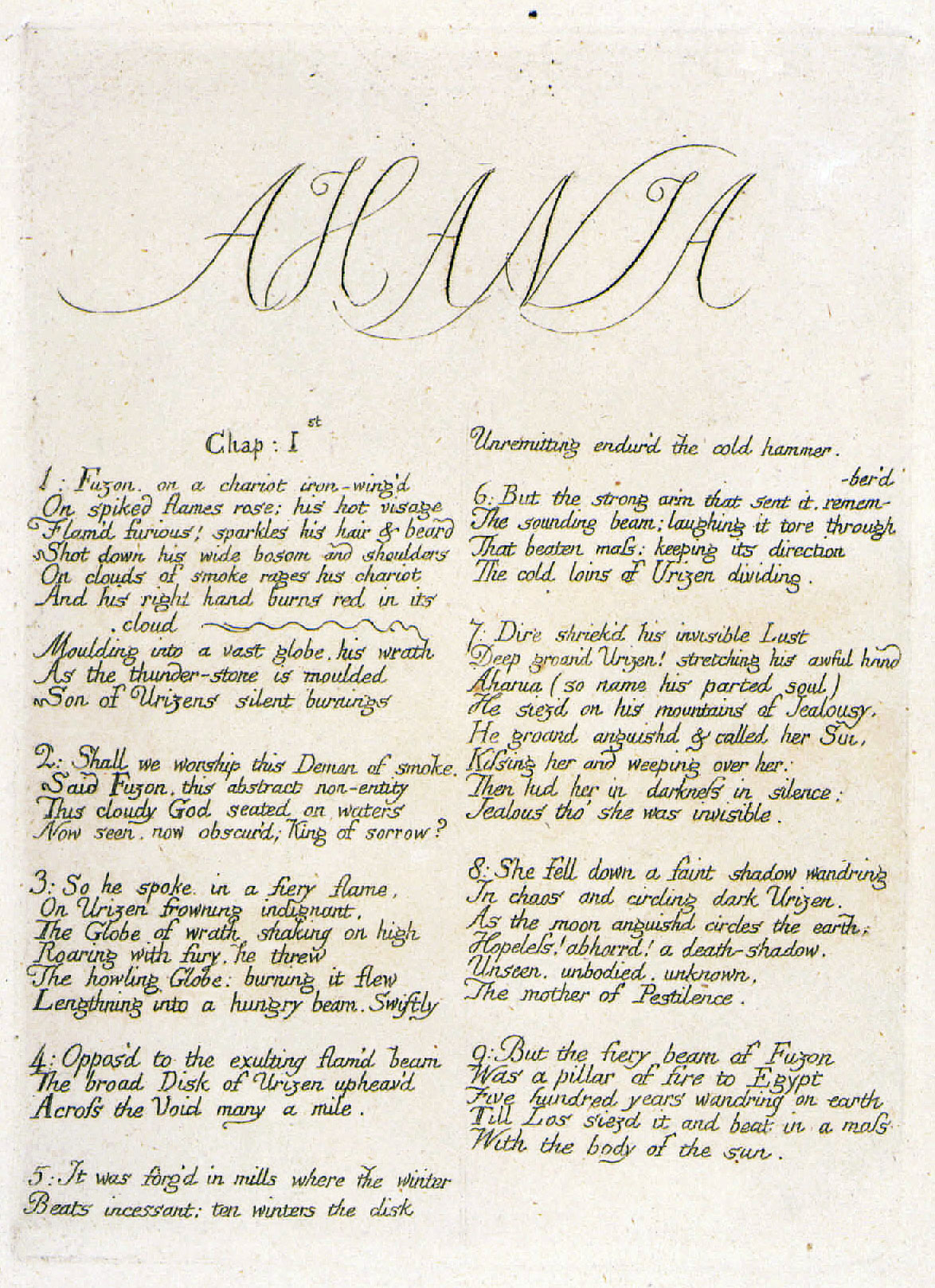

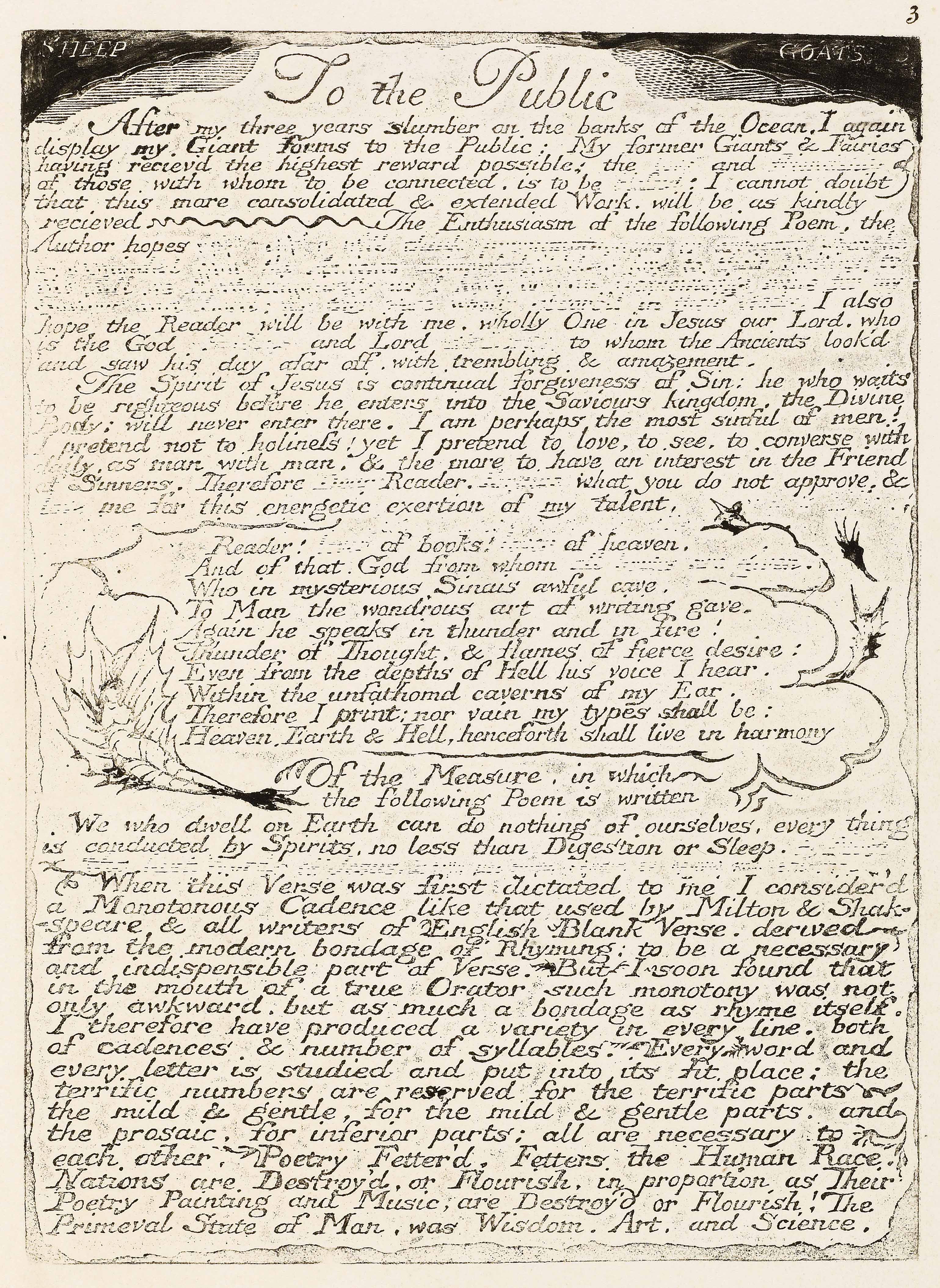

Blake is no longer the prophet of écriture. Perhaps the single statement that some young critics of the new age found most compelling in Blake, his remark in the Preface to Jerusalem that “the Ancients entrusted their love to their Writing,” has literally been obliterated. Or, leaving open a recuperative strategy, could these young critics say that Jerusalem’s traces have achieved a new dissemination? The line now reads: “the Ancients acknowledge their love to their Deities” (illus. 2). The alteration may serve as a lesson for all of us who were—or become—wholly one with the Editor’s text: CAVEAT LECTOR. (Without concern for the accuracy of Erdman’s recovered reading, we should note the effect of including in a reading “text” lines that were deleted by Blake: compare illustrations 2, 3, and 4.)

Comparing Erdman’s “text” with examples of the productions by Blake that it re-presents, we realize again begin page 5 | ↑ back to top with added force the absolute justice of the Editor’s admission that “In print it is impossible to copy Blake exactly: his colons and shriekmarks [!] grade into each other; he compounds a comma with a question mark; his commas with unmistakable tails thin down to unmistakable periods.” We realize as well the profound contradiction in the subsequent disclaimer that “In Blake the practical difference between comma and period, however, is almost unappreciable” (E 787). Contradictory, because the reader of this “complete” Blake is never “in” Blake, but is rather in the editing and altering “I” that has “been inclined . . . to read commas or periods according to the contextual expectations.” The Editor does offer the reader without access to originals or facsimiles one check on his calibration, for one of the book’s illustrations (following p. 272) reproduces plate 10 of America (copy not specified) which has twelve lines of text. Lines 7-9 of the printed version (E 55) offer the following:

Because from their bright summits you may pass to the Golden worldBut the reader of even the reproduction included in The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake will probably perceive:

An ancient palace, archetype of mighty Emperies,

Rears its immortal pinnacles, built in the forest of God

An ancient palace. archetype of mighty Emperies.

Rears its immortal pinnacles, built in the forest of God

We cannot do too much with this one instance, however, because as Erdman notes, he has prepared a “collected” edition “as against transcripts of individual copies.” The study of an individual copy of an illuminated work cannot call into question a collected transcript that has been produced as the fruit of the Editor’s compositing art. But for those several works that exist in only one copy, the individual transcript is the basis of the collected edition. One such, The Book of Ahania, offers a kind of introductory exemplum, and has the further virtue of having been printed in intaglio, which gives to its text more clearly defined lines than the usual relief etching. “Editing the works that Blake etched and printed himself,” writes the Editor, requires first of all “precise transcription.” The MLACSE has stated that it “signifies” by its emblem that this volume “records all emendations to the copy-text introduced by the editors,” according to “explicit editorial principles.” In Erdman’s printed text Ahania remembers, towards the conclusion of the book:

My ripe figs and rich pomegranatesErdman’s version leads us to think that Ahania reports to Urizen how her fruits acted, because of the comma which makes “O Urizen” into an apostrophe. But no such punctuation is visible in Blake’s plate (illus. 5). As with her exclamation six lines before (“O! eternal births sung round Ahania”) so here, in less exclamatory fashion, Ahania jumps to the catching memory that “Urizen sported and sang.” Further: evidently Ahania suggests a strange time when her fruits were the feet of Urizen. The syntax then, the mere absence of the comma, complicates considerably our image of Urizen. Such proliferating complication, struggling against “contextual expectations,” is at the core of our vision of Blake’s work. To appeal to “contextual expectations” as a neutral and universal given is to avoid the possibility that the difference between a period and a comma, or between a comma and nothing at all, is “the difference we see—and, by seeing, make.”4↤ 4 Stanley Fish, Is There A Text In This Class? (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980), p. 148. Two chapters in Fish’s book are especially pertinent to our discussion here: “Interpreting the Variorum,” where what Erdman calls “contextual expectations” are discussed by Fish as the “hazarding” of what he calls “interpretive closure;” and “Structuralist Homiletics,” where an extended analysis of a passage from Lancelot Andrewes gives more detailed examples of how an unfolding verbal and semantic structure is answerable to and shaped by our expectations for its form and meaning.

In infant joy at thy feet

O Urizen, sported and sang (5.26-28, E 89)

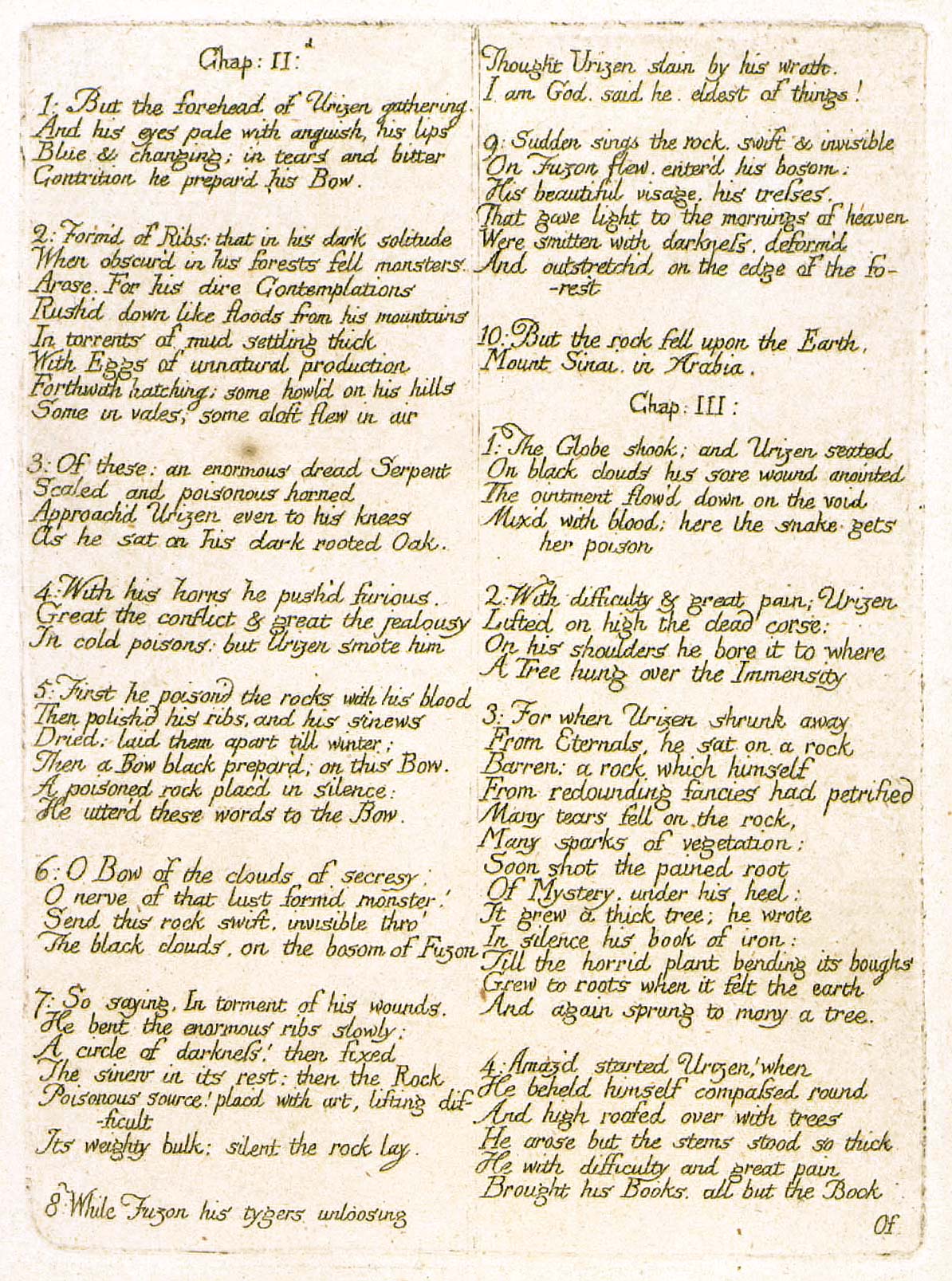

The possible complications suggested by letter configurations can be equally prolific. Consider illustration 6, showing lines that Erdman transcribes to report that Urizen “fixed / The sinew in its rest” (BA 3.32-33). This “sinew” was addressed six lines earlier in the poem: “O nerve of that lust form’d monster!” A comparison of “ ‘sinew’ ” with the “sinews” of 3.21 (illus. 6, again) suggests that the second instance may be trying graphically to become—as it is conceptually—both “nerve” and “sinew” at once, a “sinerv.” Certainly the eighteenth-century semantics of “nerve” allows us to think of a “nerve of sin,” a new sin constituted with the advent of the Rock:

So saying, In torment of his wounds.The Rock is, of course, “Mount Sinai. in Arabia.” (Erdman reads “Mount Sinai,” BA 3.46). The (material, graphic) nature of “Sin” is itself problematic. According to Erdman, in BA 2.34 Urizen names Ahania: “He groand anguishd & called her Sin,”.

He bent the enormous ribs slowly;

A circle of darkness! then fixed

The sinerv in its rest: then the Rock

Poisonous source!

Those who delight in dread terrors may see additional complexities in illustration 7. This first chapter of Ahania is much involved with “astronomical” cosmology—that is, with the “Globe of Wrath.” The first stanza ends with a description of Fuzon and/or his wrath as “Son of Urizens silent burnings” (2.9), and the last stanza concludes with the picture of the fiery beam of Fuzon seized by Los and “beat in a mass / With the body of the sun.” (2.47-48). The reader’s “contextual expectations” must point to the multiple possibilites in calling anything, especially “his parted soul” (sol—“so name his parted soul”),5↤ 5 Or, to invoke the French Blake might have known: “so name”: son âme: “his parted soul.” “S—n.” The graphics of 2.34, through the novel “n” shape and the absent dot for the “i” bear out the possibilities. Perhaps what we see happening to Urizen, his so[u]lar failing is, indeed, identified in almost all its forms as sui-sun-sin, seen one on top of the other rather than linearly. The reader’s probable query here is our answer: you reason it out.

Lest this seem too much quibbling over trifles, we should reemphasize one of the basic rules of the game: that to change anything that physically appears in Blake’s work to an editorial alternative is to “emend” the text in favor of an editorial line of interpretation. It is for this reason that the terms of the MLACSE approval state “explicit editorial principles” which include the recording of begin page 6 | ↑ back to top “all emendations to the copy-text introduced by the editors” (E VI). In his longest comment on any word or line in Jerusalem (J 21.44, E 809-10), Erdman explains why he did not emend his reading of “warshipped” to “worshipped” which would follow the common assumption that the “a” is a simple spelling mistake on Blake’s part (this reading is discussed in greater detail below). Bentley, on the other hand, prints “worshipped” in his text without comment, leaving open the question of whether he saw an “a” and silently changed it or instead simply saw and recorded an “o.” For Urizen 19.46 Bentley notes that “ ‘Enitharmon’ is spelt ‘Enitharman’ ” (William Blake’s Writings, I, 266) and presents what he assumes to be the correct spelling in his printed text. In his text Erdman prints “Enitharmon” at this point without comment. Did he see the “a” and silently correct it? If so, was it truly a “correction” or was it an unrecorded emendation to the copy text in violation of the MLACSE code? In his note to Milton 10.1, Erdman, having printed “Enitharmon” in his text, announces explicit disagreement with those who see an “a” at this point instead of an “o.” (“Not misspelled ‘Enitharman’ despite Bentley, following Keynes” E 807.)

There are two levels of interpretation intertwined in these examples. One is the graphic at the level of physical perception (“Of course an ‘a’ can look something like an ‘o,’ ” Erdman observes). The other level is the still more difficult one of authorial intention, which raises the issue of whether or not the letter in question may be a “mistake.” These problems are compounded by the issue of editorial policy or principle with respect to the category of “mistakes,” and the editorial prerogative—or presumption—to make a better “text” than the author/printer William Blake. We believe that the reader has the right to know that Blake made “mistakes,” and the even more important right to weigh the possibility that what looks like a mistake may not be one—that “Enitharman” and “warshipped” and “sinerv” might be meaningful or provide clues to meaning. But first one must see the “a” in the place of the “o” and the “rv” in the place of the “w.” Erdman does not give us the option of seeing the “a” in “Enitharman,” and Bentley does not give us the option of seeing the “a” in “warshipped.” Neither Editor gives us the synergetic possibilities of seeing “sinerv.”

Another curiosity in the “precise transcription” of Blake’s printing is the practice Erdman shares with other Blake Editors of disregarding Blake’s original line shape. Presumably to suit the exigencies of typographic economics, Editors often permit short, hyphenated lines to be printed straight through, while they gratuitously double Blake’s “long resounding” line to suit the dictates of their formats. This is inconsequential if the letters and lines are merely abstract linear vehicles of sense; but if this is not the case then the practice does violence to the visual semiotics of Blake’s printed text. In Blake, perhaps more than most poets, the arrangement of words on the printed page has a graphic potential that should not be ignored. Words (and sub-units of words) can be meaningfully associated by a vertical contiguity and patterning as well as by the more obvious syntagmatic syntactic order exhibited by the text. Consider this minor instance from Urizen as printed in Erdman’s text:

5. But no light from the fires. all was darknessIn Blake’s text—disregarding the diacritical figures and connection-lines which we grant to be outside the typographical concern—the reader will find a different experience:

In the flames of Eternal fury

6. In fierce anguish & quenchless flames (5.17-19, E 73)

5. But no light from the fires. all was darknessThe text reads up and down as well as across; vertical relationships imply a connection between “no light / darkness,” “darkness / flames” and “fierce / flames” which is repeated five lines later:

In the flames of Eternal fury

6. In fierce anguish & quenchless flames

In howlings & pangs & fierce madnessThe cumulative effect of such encoding asserts the existence of the “fires” as another presence, so that when “Los shrunk from his task”:

Long periods in burning fires labouring

His great hammer fell from his hand:Such connections lead to the core-text of 5.32-34:

His fires beheld, and sickening,

Hid their strong limbs in smoke. (13.21-23)

. . . eternal fires . . .

. . . Eternity . . .

. . . sons . . .

So too the first appearance of that son of Eternity, Los, is more problematic if, rather than reading the line straight across, we encounter Blake’s arrangement:

8. And Los round the dark globe of Urizen (5.38)(round Los = the dark globe of Urizen? = like a black globe . . . like a human heart?) The differences seem even more telling when we compare the Editorial version of Urizen 4.24 with a version that follows what Blake printed:

6. Here alone I in books formd of metalsIt is appropriate enough, in this book so polysemously predicated of Urizen, for the protagonist, speaking of his books, to describe them and himself as “I in books formd of me-.” This mind forgery is one alloyed me-tell.

6. Here alone I in books formd of metals

The transition to type also alters Blake’s spacing, and so obliterates many significant effects. In Blake’s Urizen 20.1-2 the exact correlation (and thus contrast) of:

. . . eternity:becomes in Erdman’s text:

. . . Eternity.

Stretch’d for a work of eternity;begin page 7 | ↑ back to top For another example in this vein, we note that Blake’s “Ah !SUN-FLOWER” (not Erdman’s “Ah! SUN-FLOWER”) begins “Ah Sun-flower ! weary of time.” rather than “Ah Sun-flower! weary of time,” as in Erdman (and Bentley and Keynes). To conclude these issues regarding “precise transcription,” consider the new rendering of Urizen 3.26: “The petrific abdominable chaos” (the MLACSE award assures us that the volume “has been scrupulously and repeatedly proofread to prevent unintentional alterations”—but note also the heading, p. 85. The editor, to be sure, knows that every “new printing will have its own fresh errors”).

No more Los beheld Eternity.

II. A DIGRESSION ON FORM AT MISE—EN—PAGE

Format: general plan of physical organization or arrangement.

No matter how unconscious we are of the effects on our mode and mood of perception, we are constantly influenced in our reading by how a poem looks on the page. Our first glance at a new poem can reveal a traditional form printed in metrically-regulated neat stanzas, suggesting among other things how the poem will sound or feel to our ears. A glance at a poem in free verse with a wide variety of line lengths will create quite different expectations of the nature of what we will be experiencing as we read the words. As John Hollander remarks in Vision and Resonance: “The very look of the received poem on the page jingles and tinkles today the way neat, accentual-syllabic rhyming once did” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975, p. 240). Part of the formal content and context of any poem, then, will be perceived in our encounter with the image made by the words as they are printed on the page which represents our field of vision. For the most part the effects these visual arrangements stimulate do not receive our direct attention. We only notice them in a printed book when they obtrude themselves upon our consciousness, disturbing the generally bland and neutral matrix of subordination that is supportive of the often desired effect of reading the poem through a transparent medium.

The normative tendency in letterpress or offset printing seems to be the disposition of words on the page in a way that is essentially arbitrary and meaningless in itself, with page breaks simply coming when the available space has run out. With printed prose, only paragraph indentations break the monotonous scanning motion of the eyes; with poetry a few more flexible and varied options are accommodated by the format, but financial expediency and typographical proprieties tend to keep these at a minimum. The form of the book is extensively and efficiently coded by the nature of the processes involved in its production, and the finished result operates to structure the reading process in ways that are compatible with that code. Since reading involves the ability to distinguish functional units through visual identification, anything we perceive as surrounded by white space will be a semiologically significant unit. In conventional typography the units are almost exclusively semantic ones: words, lines, paragraphs or stanzas.

A growing body of research suggests that much of perception, even up to fairly high interpretive levels, is automatic and independent of conscious awareness. The effects of peripheral vision are especially powerful in this regard, and it has now often been shown that what we are unaware of seeing is nonetheless influencing what we see and how we feel about the content of our consciously focused vision.6↤ 6 Cf. Tony Marcel, “Unconscious Reading: Experiments on People Who Do Not Know That They Are Reading,” in Visible Language, 12.4 (Autumn 1978). Julia Kristeva, among others, has emphasized the importance of visibility as a component in establishing the semiotic modality and meaning of a work: “The lines of a grapheme, disposition on the page, length of the lines, blank spaces, etc. . . . contribute to the building of a semiotic totality that can be interpreted along multiple paths, a substitute for thetic unity.” La Revolution du langage poetique (Paris: Seuil, 1974), p. 219.

Further understanding and appreciation of Blake’s poetry calls for more attention to conceptual structures in his visual semiotic and to what might be called the visual syntax of his written work. “Vision” is a key term for Blake, and the visual form of his poetry, especially as it violates traditional linear forms, is an important functional element of his work—though even W.J.T. Mitchell, who has advanced our understanding of Blake’s “composite art” more than anyone else, still accepts a primary distinction between the (non-visual) poetry and the illustrations.7↤ 7 See Blake’s Composite Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978). At the “Blake and Criticism” Conference held at Santa Cruz in May 1982, Mitchell remarked that while working on Blake’s illuminated poetry he “had to have a printed version of the poetry in order to read it.” To explore the visual syntax of Blake’s poetry and to grasp the visual statements he creates requires paying attention to a variety of features that are unavailable in the conventionally presented editions of his work.

Among these, perhaps the most fundamental to the emergence of visual form are figure-field relationships. Every semantic unit is seen with respect to its background, and it establishes its own particular visual presence in terms of its magnitude (both size and shape), position, and orientation perceived against this background. Some of the main factors which influence our reading of figure-field relationships, as pointed out by Arnheim, include texture, spatial proximity, the qualities of enclosed forms, vertical distinctions between bottom and top, horizontal vs. oblique positioning, convexity of forms, suggestions of overlap, and consistency or simplicity (or their opposites) in shape.8↤ 8 Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954), pp. 32-81. Even if the visual stimulus is physically two-dimensional, it contains clues that influence the viewer’s perception and evoke a reading of implied depth, making the figure-field relationship a distinctive aspect of the syntactic meaning.

Reading Blake’s work in the original or in facsimile takes time, which leads most of us to try to “get” the poetry from a printed edition while studying the plates for purely visual information. Our ability to read has been conditioned by our familiarity with traditional linear text forms and the consistent and powerful appearance begin page 8 | ↑ back to top they present, which stimulates and rewards certain conventions of reading, while affecting the dynamics of the reading experience. In this experience the poem presents itself to the reader as centered within or on a single abstract plane. We engage the visual composition at the upper left and scan line after line horizontally while picking up information and rhythmic impact visually from variations in line length and from variations in typographic forms (e.g., capital letters) and punctuation. The margins framing our encounter with the text are typically large, neutral, and relatively consistent. The figure-field relationship of the poem is one of neutrality, and the interior visual syntax of the poem is empty of significance, with maximum consistency in spacing between letters, words, and lines. Where variations in spacing are required to justify line-endings they are often made as subtle as possible in the attempt to keep them below our threshold of perception. Blake’s poetry, in contrast, persistently violates and challenges our assumptions about the proper orientation of visual symbols in a field, as well as about their shape, size, orientation, color, physical material and texture. There is crucial information of a visual-semiotic nature in Blake’s disposition of individual letters, words, sentences and other semantic units on his printed page, and in the visual boundaries that make such disposition possible. At least some of these effects can be hinted at even within the physical and economic constraints of the typographic medium, and Editors of Blake should be much more imaginative and insistent in their attempts to do so.

The format of individual pages in a book is of course only part of the impact made by the material form of the text on the reader. There are numerous intrinsic properties attendant upon the design and order of books and their component parts. The effects generated by the emblematic characteristics of the book will constitute a significant part of the terms on which the contents of the book are offered and received. In the conventional printed book the assignment of text to a given page is arbitrary or even accidental; yet the turning of a page is a vital act performed by the reader, one which is structured in relation to the poem’s form and meaning by where and how the text has been separated by the printer. To quibble over commas and periods, while randomly introducing “punctuation” on the magnitude of page division, is a bit like swallowing the camel and choking on a gnat, in terms of the impact on the visual and semantic structure of the work. Divisions that Blake made are not functionally present, while divisions he did not make are operative—and juxtapositions can be as significant as divisions. How are we to measure the impact of Erdman’s page 144, where the “Finis” of Milton is separated from the title Jerusalem by only ¾ of an inch and the intervening two-leafed tendril that he used at tops of pages in The Illuminated Blake (illus. 8)?

Blake’s constant attention to the overall form of his “books” and to minute formal nuance within them should pose a challenge to the Editor to try to achieve as many of Blake’s effects as the typographic medium will allow (as David Erdman does, for example, in his remarkable edition of The Notebook of William Blake), rather than disguising those effects and lulling the reader into believing that he is getting the “book” as well as the poetry in the book. This might lead to expensive decisions about blank space in some cases and non-blank space (e.g., narrow or minimal margins) in others. It might not be considered worth it to print Urizen on only one side as Blake did, but the possibility should be considered before going to press, along with the possibility of presenting the text in the original bicolumnar form which constitutes one of its most conspicuous and meaningful features. The Book of Urizen is an especially important case in point, because in it Blake was concerned not only with “writing” but also with the “bookishness” of the book, with the problem of the book as an object, a volume which offers its contents in terms of its physical and formal properties as an object. Blake’s Urizen is designed within a specific historical and contextual field of purposes, conventions and assumptions; yet while designed within them, it is also engaged with them in intellectual warfare. Blake’s books are addressed to the “Reader! of books!”9↤ 9 Or to the “Reader! [lover] of books!” or to the “Reader ! lover of books!” (the first from E 145; the second from the Trianon Press typographical reprint included with its facsimile [1952]). Blake did not “write texts”—he made books which posed a critique of the book-making practices of his own era, and which challenge all future readers and editors to confront the nature of books as material embodiments of texts.

If we move from considerations of format at the level of mise-en-page to the organization of the volume as a whole, we encounter difficulties with Erdman’s text that are not necessarily limited to the typographic medium of reproduction. Erdman continues to reject the organizing principle of chronology that leads other Editors to attempt to present Blake’s works in the order of their composition. Instead, he conceives of four more or less parallel chronologies which are presented consecutively: works in illuminated printing; “prophetic works” never engraved; other works, mostly lyrical, never engraved; and miscellaneous “late prose treatises, marginalia and letters.” Within each of these categories “a rough chronology is observed, but only when thematic or generic relations fail to offer more meaningful groupings” (XXIII). The lines separating these categories are somewhat obscured by their numbering, with the first two each marked by its own Roman numeral, the third category marked by five Roman numerals (III-VII) and the fourth marked by eight Roman numerals (VIII-XV). Within these subdivisions a section like The Everlasting Gospel or the 1809 Descriptive Catalogue may occupy a specific moment in Blake’s career, while others—the letters for instance—encompass its whole range. The fundamental begin page 9 | ↑ back to top organizational unit, in other words, is not chronology but format (a format most wearing on the book after even moderate use). We must therefore note that while Blake’s production format is deleted or effaced by editorial and print technologies, some aspects of his actual format survive in E in this awkward and vestigial organizational structure.

There are further consequences and complications. Erdman sensibly prints Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience back to back, whereas a stricter chronological principle (as followed by Keynes and Bentley) would have had to place Experience among the later Lambeth books—next to Urizen, perhaps, where another set of thematic implications might appropriately be emphasized. Better still might be to print Innocence twice, once where E has it then again later on with Experience, thereby reflecting at least some of the shifts and revisions which this new context suggests. There were not, after all, always two contrary states of the human soul. In Blake’s project, one printing of title A can precede a printing of title B, with a reprinting of title A following B and incorporating revisions inspired by B. A2 could influence changes made in a printing of B2 so that a satisfactory chronology of Blake’s works cannot be determined solely on the basis of first copy (e.g., title-plate date). Even if all these dates were clearly determinable, which they are not, Blake’s ongoing revisions render the establishment of a chronological canon of his work—even within Erdman’s format categories—essentially problematic.

We must conclude that there is no clearly satisfactory answer to the editorial problems imposed by the nature of Blake’s oeuvre and by the decision to publish “all” of Blake in a single volume. A one-volume Blake reduces much of the potential integrity of individual books, and physically limits and prestructures the potential range of patterns of relations between them. The sense in which we can have “all” of Blake in a single volume might therefore induce in the reader even more than the usual sensation of claustrophobia, of being—with Macbeth—“cabin’d, cribb’d, confined, bound in.” If the desire of the reader of Blake is truly Infinite, so that “less than All cannot satisfy,” then that desire will be to have more truly at his or her disposal all of Blake—individual photographic copies, at least, of every copy of every illuminated book, every manuscript and notebook and annotated book and letter: A Complete Blake Unbound, the imagined existence of which will provide the best measure of the inevitable limitations of any specific Editorial production.

III. [MORE] MINUTE PARTICULARS

Let us return to the problem of Blake’s punctuation, with the honest and grateful acknowledgement that David Erdman has done more than any previous editor to free us from our programed desire for conventional syntax. Erdman is, in places, not at all uncomfortable with Blake’s short periods:

2. That Energy. calld Evil. is alone from the Body.Such periods break up completion. logical syntax, and invite the reader. to a more active, participation in the production of text. Blake could use commas elegantly when he chose, as in the following quotation (where our reading of MHH copy D tallies exactly with that offered on E 39):

& that Reason. calld Good. is alone from the Soul.

(MHH 4, E 34)

But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged; this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

But still, there are more periods in Blake than in Erdman, and we need to accept them as such if we are truly to grapple with the at times discontinuous folds of Blake’s syntax. “Truth can never be told so as to be understood. and not be believ’d.” (E reads “understood,”). “I must Create a System. or be enslav’d by another Mans” (E reads “System,”). Periods can be banished completely, rather than be demoted to commas, if Erdman finds them “intrusive” (E 808), as he does the one after “dance” in Milton 26.3:

Thou seest the gorgeous clothed Flies that dance & sport in summerWith the removal of this “intrusive” period vanishes the mazing possibility of weaving not only a dance of Flies, but also a dance of sunny brooks and meadows. So vanishes, perhaps, another “Period” in which “the Poets Work is Done”, that startling stop in which, by which, “Events of Time start forth & are concievd in such a Period” (29.1-2). In Blake’s “London” (E 27), we can instructively compare lines 5-8 as transcribed by Erdman with what appears in copy C:

Upon the sunny brooks & meadows: every one the dance[.]

Knows in its intricate mazes of delight artful to weave: (E 123)

In every cry of every Man,The next stanza of the poem, amplifying the unending line of the preceding one and the first line of the last, gives us an example of Blake’s vertical ordering that does not elude the typographic medium: begin page 10 | ↑ back to top↤ 10 For further discussion, see Nelson Hilton, Literal Imagination: Blake’s Vision of Words (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), pp. 63-66.

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

In every cry of every Man.

In every Infants cry of fear.

In every voice: in every ban.

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

How the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sign

Runs in blood down Palace walls

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

(E 27, emphasis added10)

Another minute particular involves what Erdman calls “one kind of silent insertion”—the occasional addition of an apostrophe to the possessive of Los. Without the apostrophe, Erdman notes, we are “otherwise subject to confusion with ‘Loss’ ” (E 787). So, for example, we have this Editor’s Spectre “driven to desperation by Los’s terrors & threatning fears” (J 10.28, E 153) rather than by “Loss terrors & threatning fears”. Yet the Spectre speaks precisely out of an intense sense of loss (“Where is my lovely Enitharmon,” “Life lives on my / Consuming”). Blake knows as well as Milton or Lacan that our feeling of “loss” feeds (“unwearied labouring & weeping”) our emotional and imaginative life. Los’s possession is loss (to our profit);11↤ 11 On this still much neglected pun, see also Aaron Fogel, “Pictures of Speech: On Blake’s Poetic,” Studies in Romanticism, 21 (Summer 1982), 224. and these references can be connected to the solar aspect of Los’s name as well, for when we can go inside out and see even our sun as a loss, then we have solace.

IV. PART

ICULAR MINUTENESSES: A DIGRESSI

ON THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS

I have a disease: I see language (Barthes)

For the weak, merely to begin to think about the first letter of the alphabet might make them run mad forthwith. (Rimbaud)

For A is the beginning of learning and the door of heaven. (Smart)

For that (the rapt one warns) is what papyr is meed of, made of, hides and hints and misses in prints. Till ye finally (though not yet endlike) meet with the acquaintance of Mister Typus, Mistress Tope and all the little typtopies. Fillstup. (Joyce)

One would not presume to speak of—or practice—editing a painting or a sculpture, no matter how valuable and useful the attempt to represent such objects in photographic and book form may be, because of the essential materiality of their mode of existence. Nor, we would assume, would anyone try to correct Joyce’s spelling in Finnegans Wake in order to make it easier for the reader to get at the “text” of Joyce’s work. The problems with the Erdman edition and related matters we have been discussing so far have all been within the context of exploring and recommending what is possible in attempting to achieve a typographic representation of Blake’s work. In this digression we will emphasize even more the negative (the Loss) in any edition of Blake that uses typography. We do so not in the spirit of fetishizing the unique original as a sacred relic, or of endowing it with some magical authority because it was physically assembled by Blake, but rather from the conviction that a significant part of the complete poetry of the illuminated books is a visual-verbal semiotic in which form and meaning cannot be separated from material substance, or the adequate representation of the materiality of substance.

We wish to call attention to the visual aspects of linguistic communication in writing in general, but more particularly in Blake, as our concern moves from an awareness of graphic space as a structural agent on a large scale (page format and “book”) to the minutiae; from an emphasis on the spatial-structural relationships of the linguistic materials to the actual materiality of the signifiers: their “concreteness” in a perhaps metaphorical sense, their “visibility” in a literal sense.

There seems to be a pervasive cultural and intellectual tendency to suppress the graphic element of writing, its graphology. For the general linguistic approach to the study of language, the primary function of writing systems (with the occasional exception of ideographic or hieroglyphic forms) is to give phonological information. But ink—like air disturbed into sound and patterned into words—can also be a linguistically patterned substance, a different medium, and one which by its very nature is not invisible or transparent. Yet the typographic production of books in the usual manner strives for invisibility or transparency of its signifiers in the service of the idealized “text.” If we print or write the word “red” in red ink, there may be a non-arbitrary relationship between the graphic signifier and its signified; and this is only a simple and obvious instance. As soon as we come down with the Barthesian dis-ease of “seeing language” we enter a combined semantic and visual semiotic field in which an enormous range of meaningful effects becomes possible. For Blake this was not a neutral possibility, but a poetic necessity: “Writing / Is the Divine Revelation in the Litteral expression” (M 42.13-14, E 143), and the literal letter (Lat. littera) is the medium of the revelation, as doubly indicated by Blake’s spelling. Earlier we mentioned that Mitchell, in his valuable book, has separated the poetic text from the visual text in his dialectical approach to Blake’s composite art. We want to suggest that something like Mitchell’s “dialectic” is going on within the poetry itself, and that more attention to and respect for that visual form is long overdue, to appreciate a different form of “composite” art which combines a heightened visual and acoustic attention to Blake’s signifiers (i.e., not to his “text”).

To “see” words can be considered a disease because it is non-normative. It may be typical, as Freud said, of the state of consciousness present in dreams, but it is a deviational mode of attention verging on epistemological error in our ordinary state, much as attention to particulars was aesthetic error for Reynolds’ aesthetic of the grand style. Linguistics tends to share this attitude through its definition of the mode of existence of language, with graphological forms as purely arbitrary indicators of phonological begin page 11 | ↑ back to top acts. The historical theory and practice of typography are complicitous with the same set of assumptions and values. The fundamental aim of typography as a practical discipline is to achieve a state of invisibility, a type so “legible” that the reader looks through it not at it. How are we to understand this self-effacement? The goal in this practice is to make print a perfectly functional language medium, which is to ignore the difference between spoken and written utterance—to ignore the fact that the necessity of vision is built into the production of writing, the reproduction of writing, and the reception of writing in the literate mind.

It is one of the strongest conventions within the dominant mode of book production that the materiality of the printed sign-vehicle be ignored as non-iconic. It is not printing per se that is at issue, for Blake printed his own work from what he called “stereotypes,” adopting the word from conventional printers’ usage. It is rather the desire to make the medium transparent in the service of a disembodied “text” which negates Blake’s persistent efforts to exploit the materiality of his mode of production as a significant part of the potential meaning of his work. The form of Blake’s work signals a change of signfunction, with its marked departure from linear printing, and challenges the reader to a different mode of reading. We are arguing that it is neither a “service” to Blake nor to the reader of Blake to make the experience of reading him easy or convenient. It may at first seem fanciful to suggest that to “buy” meaning from Blake requires—in the sense of classical economics—an exchange of labor of comparable value. But Blake could easily have “written” his works for the typesetter and saved himself and us enormous labors—especially us, since his writings would very likely not have been published at all. How much of what he put into his “works” can we get out if we continue to make things as easy as possible?12↤ 12 Cf. the policy of the Longman Annotated English Poets Series, as written by F.W. Bateson: “the series concerns itself primarily with the meaning . . . . whatever impedes the reader’s sympathetic identification with the poet . . . whether of spelling, punctuation or the use of initial capitals—must be regarded as undesirable” (The Poems of William Blake, ed. W.H. Stevenson [London: Longman, 1971], p. ix). Although this edition is described on the title page as having “text by David V. Erdman” (i.e. poems of Blake, text by Erdman), the policy of the series produces (and, of course, copyrights) a “text” out of the “text”—a “text” which asks us to identify sympathetically with its text-destroying pretense that “writing/Is the divine revelation in the literal expression—.”

What we mean by the “iconic” dimension of Blake’s writing is not a naive privileging of the authority of the author’s own handwriting as authenticating “signature” of presence. It is more like the definition that Peirce gave of a motivated relationship between the iconic sign and its object, where the iconic sign is “like [some]thing and used as a sign of it.”13↤ 13 Charles Sanders Peirce, Elements of Logic, Collected Works, vol. 2, ed. Hartshorne and Weiss (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1932), p. 143. We would not limit our use of “iconic” as Peirce does, to cases where the qualities of the iconic sign must “resemble” those of its denotatum and “excite analogous sensations in the mind for which it is a likeness” (p. 168), because resemblance is too narrow a limit to assign to the iconic-function potential. Resemblance is only the most obvious of the motivating connections that can exist between the shape of individual letters, their combination into words and larger units, their color, material substance and form, and what those letters mean, or stand for, or represent, or signify.

To maintain that Blake’s writing is visible or iconic means that a signifying process is functioning which cuts through, disrupts, and challenges the ordinary reading process without necessarily destroying it or superseding it. Blake’s signifying practice must be sensed through both auditory and visual means, and there is no reason why the same writing cannot give evidence of both operations simultaneously at work—or play. In this context we want to return to the instance of “warshipped” mentioned above, and the difficulty in determining whether it is, in Erdman’s words, “an error for worshipped” or “possibly a punning coinage.” What we have here is not simply a physical question of seeing, but a complex perceptual field which includes the possibility that a problem of seeing (“o” or “a”) may relate to a mode of hearing. Tony Tanner has argued for a conceptual relationship between puns and adultery in the novel, suggesting that two meanings that don’t belong together in the same word are like two people who don’t belong together in the same bed.14↤ 14 “ . . . we may say that puns and ambiguities are to common language what adultery and perversion are to ‘chaste’ (i.e., socially orthodox) sexual relations. They both bring together entities (meanings/people) that have ‘conventionally’ been differentiated and kept apart; and they bring them together in deviant ways, bypassing the orthodox rules governing communications and relationships. (A pun is like an adulterous bed in which two meanings that should be separated are coupled together). It is hardly an accident that Finnegans Wake, which arguably demonstrates the dissolution of bourgeois society, is almost one continuous pun (the connection with sexual perversion being quite clear to Joyce).” Adultery in the Novel (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), p. 53. Tanner’s is an important comparison, because there is in each case a “law” of propriety that is being broken. The overdetermination of a lexeme by multiple meanings that it does not carry in ordinary usage violates a cultural sense of textual and linguistic propriety. When this happens in Blake, the visual lexeme can be an important functional component of the auditory experience, and provide a simultaneous violation of the linearity and univocity of discourse (cf. illus. 9).

We want to emphasize that we are not dealing here with a trivial textual crux, which may or may not be resolved definitively by improved photographic techniques. We are dealing with an editorial practice (relaxed in this case by Erdman), with ontological notions of the “text” that call for a typographical transparency in the material manifestation of that text. When Byron yearned for words that are things, he was using a metaphor implying a non-human language, the unmediated generative speech of God, or at least a long-lost referentiality of language. But the Blake text insists on the materiality of its words as things in a literally literal sense, the sense in which Freud could say that “Words are a plastic material with which one can do all kinds of things,” and the sense in which W. H. Stevenson is ironically not being literal when he changes Blake’s “Litteral.”15↤ 15 Sigmund Freud, Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (New York: W.W. Norton, 1960), p. 34; on Stevenson, see note 12, above. Freud frequently uses metaphors of writing in his representation of the unconscious. In The Interpretation of Dreams he speaks of the symbolism of dreams in general as a cryptography or rebus, a hieroglyphic or pictographic script, but notes more specifically that “It is true . . . that words are treated in dreams as though they were concrete things, and for that reason they are apt to be combined in just the same way as presentations of concrete things. Dreams of this sort offer the most amusing and curious neologisms.”16↤ 16 Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, tr. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, n.d.), pp. 295-96. For Freud words are presented in the unconscious in ways that must be distinguished from the perceptual mode of consciousness, which looks through the word only for its lexically coded signification. Something that is ordinarily begin page 12 | ↑ back to top invisible to consciousness is ordinarily visible in the unconscious, and the interpreter must see language differently, must stop short before the accepted or expected meaning of a word in order to perceive language in its material density. A certain amount of regression may help the interpreter in this enterprise, since “the habit of still treating words as things” is most common in children, and is “rejected and studiously avoided by serious thought.”17↤ 17 Freud, Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, p. 120. Freud’s formulation here suggests that the “habit” is not automatically outgrown. It must be rejected and studiously avoided, and “when we make serious use of words we are obliged to hold ourselves back with a certain effort from this comfortable procedure” (p. 119).

When Freud moves on in Chapter V of Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious to consider the general question of the subjective determinants of jokes, he makes some interesting speculations on the relationship between joke-work and the infantile as the source of the unconscious, suggesting that “the thought which, with the intention of constructing a joke, plunges into the unconscious is merely seeking there for the ancient dwelling place of its former play with words. Thought is put back for a moment to the stage of childhood so as once more to gain possession of the childish source of pleasure” (p. 170). But playing with words, like playing with feces, is not countenanced by authoritative parents (or editors). Thus, “it is not very easy for us to catch a glimpse in children of this infantile way of thinking, with its peculiarities that are retained in the unconscious of adults, because it is for the most part corrected, as it were, in statu nascendi” (p. 170). It may well be that a large part of the editor-work is operating over against something like Freud’s joke-work in the production of the idealized Blake “text.” Freud emphasizes that the “laugh” can function as a confirmation of the possibility that Witz has a profound relationship to instinctual drives already at work in infancy. Laughter can dismiss as “children’s ‘silliness’ ” that which the adult must reject and studiously avoid when he makes “serious use of words.” In this context the laughter advocated by a serious arbiter of the arts takes on a certain nervous resonancy: “One would laugh at a writer who would wish his text to be printed now in small unspaced type fonts, now in large spaced ones, or in ascending and descending lines, in inks of different colors, and other such things.”18↤ 18 Alain, Systeme des Beaux-Arts, in Les Artes et les dieux (Paris: Gallimard, 1958), p. 439, quoted in Leon S. Roudiez, “Readable/Writable/Visible,” Visible Language, 12.3 (Summer 1978), 240.

What we can see and hear in Blake is influenced by what we expect to see and want to see; our desires for a purely phonological information and a “pure” lexical codification of that information make it difficult both to see and to accept the unexpected. To put a letter different from the expected one is a disruptive act, one which has the effect of engaging with other signifiers in the near vicinity. This engagement can be visual (we can see “ear” in “hear” or “orc” in “force” or “los” in “close”) and phonetic. The surrounding visual and phonemic area becomes charged and structured (or unstructured and skewed) in ways not immediately or ordinarily available to consciousness in conventional reading. Such disruptions hint at the force of a desire which is ordinarily censored, a desire for play, for unconfinedness, for regression, perhaps even for subversion. But to speculate on the identity of the force of desire requires a recognition of the effects of that desire, and an unconscious mode of censorship that screens out “what ought not to be” in the text, in language, in the psyche—with hints of an uncanny gap between the subject and his discourse in which “language” seems to be acting on its own, or where the unconscious usurps language as the servant of a subversive desire rather than the servant of well-mannered thought and the communication of sharable meaning. As Wordsworth observed, in commenting on how words can be “things”: “ . . . they are powers either to kill or animate . . . a counter-spirit, unremittingly and noiselessly at work to derange, to subvert, to lay waste, to vitiate, and to dissolve.”19↤ 19 “Essay on Epitaphs II,” in The Prose Works of William Wordsworth, ed. W.J.B. Owen and Jane W. Smyser (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), pp. 84-85. At times editing can seem to a kind of toilet training of the text, or the work of a normalizing or idealizing airbrush removing all blemishes on its pure surface. Too often with the “blemishes” go a whole range of potential semiotic effects produced at the level of the letter, rather than the word or the sentence.20↤ 20 When such effects can’t be censored in statu nascendi as Freud suggests, they can be laughed at as childish. If they can’t be laughed at, the metaphors that become available for describing them are revealing. Susanne Langer has argued against the possibility of a “marriage” between the visual and the verbal in art, asserting that there are “no happy marriages . . . only successful rape” (Problems of Art: Ten Philosophical Lectures [New York, 1957], p. 86, quoted in Mitchell, Blake’s Composite Art, p. 3). The metaphor of rape is even stronger than Tanner’s analogy between puns and adultery. Under the rubric of the “concealed offense,” Kenneth Burke discusses various puns and sound effects among “the many modes of criminality hidden beneath the surface of art” (see The Philosophy of Literary Form [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973], pp. 51-66).

If we are right in our emphasis on the integral semiotic significance of the visible signifier in Blake, a number of consequences follow. For example, the question of “format” raised above becomes even more complex. If we load the individual letters with significant visibility, then the contextual field in which they appear will be changed also, with an even greater emphasis on the complete two-dimensional page over against the more limited linear path traced through the page by the normal itinerary of the printed text. Printing itself is not the problem, as we have said before. The main criterion for print is simply the existence of an “image carrier” that allows large numbers of nearly identical images to be produced from it. The image carrier can be anything from an engraved plate to a letterpress form to a photographic film or magnetic tape. The unique feature of Blake’s printing in the illuminated books is that he was printing traces or representations of marks he himself had made (“Grave the sentence deep”—and print it). Thus although he produced printed works, they retained—even before he did additional work on the prints—evidence of what Arnheim has called “writing behavior,” pointing out that “to the extent to which a reader perceives written material as the product of writing behavior, kinesthetic overtones will resonate in the visual experience of reading,” producing kinesthetic connotations that tend to transform our perception of the field from a vertical to a horizontal field of action. The implied motor behavior of writing thus emphasizes the surface of the page “as a microcosm of human activity, dominated by the symbolism of relations to the self: close and distant, far and near, outgoing and withholding, active and passive.”21↤ 21 “Spatial Aspects of Graphological Expression,” Visible Language, 12.2 (Spring 1978), 167. Blake’s writing behavior when he was engraving words on a plate was different from his manuscript activity when working on The Four Zoas, begin page 13 | ↑ back to top which poses additional considerations of its own—some of which will be taken up in the next section. But his mode of production insisted on making that writing behavior visible, with the consequences that we have been trying to emphasize. It is unusual, more difficult to read, calls for a different mode of attention, and reminds us that the body was involved in the process of production. When Blake invokes his muses, he asks them to descend “down the Nerves of my right arm” (M 2.6, E 96).

V. FURTHER [INSOLUBLE?] PROBLEMS

The complexities of the ms, in short, continue to defy analysis and all assertions about meaningful physical groupings or chronologically definable layers of composition or inscription must be understood to rest on partial and ambiguous evidence. (Erdman on The Four Zoas)

What if we then accept this as the major edition, accept its inevitable errors or questionable readings, accept its concessions to print technology—is that all one need say? One’s belief in the necessity of such concessions is dependent on a sense of the necessity of print editions themselves; and if we read Erdman’s as if it were Blake’s own text, even knowing that it is not, it will be in order to avoid a constant consideration of the concessions, or in order to induce one’s students into a more immediate, unmediated confrontation with the text. But this review continues to exercise lingering doubts about editing and typography themselves, about their very necessity.

A Shakespeare editor must be concerned that variations between the Folio and Quarto editions of King Lear represent different and perhaps irreconcilable notions of how the play was written or performed at different times.22↤ 22 The problems of editing Shakespeare in general, and Lear in particular, have led to a powerful interrogation of conventional editorial practices, and to the disturbing necessity of facing the existence of multiple substantive texts of Lear. The trailblazing essay on this topic is that of Michael J. Warren, “Quarto and Folio King Lear and the Interpretation of Albany and Edgar,” in David Bevington and Jay L. Halio, eds., Shakespeare: Pattern of Excelling Nature (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1978), pp. 95-107. The theatrical differentiation of the Quarto and Folio versions has been explored in great detail by Steven Urkowitz in Shakespeare’s Revision of King Lear (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980). A volume of essays focusing on the two texts of Lear and on the editing tradition, edited by Gary Taylor and Michael J. Warren, is forthcoming from Oxford (to be called The Division of the Kingdom). The relationship between editing practice and typography has been extensively explored by Randall McLeod in a number of articles that are pertinent to our critique in a variety of ways, most recently in “UN Editing Shak-speare,” SubStance 33/34, 12.1 (1982), 26-55. With differences in performances, print is resubmerged in subsequent productions; these productions tend not only to reinterpret but to re-edit the play as well. The problem is not simply one of editorial methodology but of fundamental differences between performance and print situations, differences obscured or obliterated by the phenomenology of print itself. In the case of Blake the problem is just as striking, for here we are obviously faced with different forms of print, materially different values of production. Blake’s production is itself a performance situation, a “scene of writing” which continually draws attention to itself as graphological production. The possible “sinerv” of Ahania or Urizen’s “books formd of me- / -tals” are not only polysemous, they also rouse the reader to such a graphological awareness. Someone is/was actually writing. If print is so fixed and final and regular as to be virtually self-effacing, Blake’s writing is self-reflective or reflexive as material production and multifold in both meaning and form. It is now commonly believed that Blake’s methods of engraving and copperplate printing purposefully set themselves apart from industrially-determined print technologies; his practice may even have constituted an active critique or subversion of what Walter Benjamin has called the age of mechanical reproduction, anticipating Brecht’s combined aesthetic and ideological insistence on exhibiting—rather than hiding—the means of producing the artistic effect.23↤ 23 For an excellent discussion of Blake’s practice in the context of the commercial norms of the time, see Morris Eaves, “Blake and the Artistic Machine: An Essay in Decorum and Technology,” PMLA 92.5 (October 1977), 903-927. The variety in the existing copies of the Songs may lead us to constitute, in part, a sense of a kind of metamorphic variance under a general controlling aegis or governing form which we call “the” Songs. But in another sense, those varieties undermine and contradict the very notion of such a generality. It is difficult to speak of the Songs entirely as if “it” were a single text, and such a difficulty can be very useful for Blake’s readers. The printed hybrid editions, however, rob the reader of that difficulty by presenting an editorial fiction based on the implicit assumption of the existence of an “ideal text” which they are representing in the most adequate fashion. If this is the case, then any print edition, no matter how “accurate” to the letter of the text, will necessarily represent a counter subversion, a recuperation of Blake’s text by the very forces it sought to oppose.

One of Erdman’s many virtues as an editor is that he has always tended to be hospitable to minute graphological particulars. If print forces the necessity of compromise, he makes fewer than most editors. Earlier editors were so accommodating to the standards of print and public taste that they often seemed like schoolteachers correcting a messy or overly-inventive child. Where Keynes, for instance, regularly normalized spelling and punctuation, one always feels a greater confidence in Erdman because he tends not to normalize, because his editions look more like the original texts, even though not as much like them as print technology might allow if fully exploited. If we have taken occasion in this review to indicate passages where Erdman is not fully consistent with this practice, where he does normalize, it should not be taken as a sign that we fail to appreciate his work as the considerable advance over previous editions which it often is. Indeed, if anything, we might express the fear that these virtues constitute a danger if they lull the reader into a false confidence that he now has the Blake “text” in his hands, lacking only the illustrations for a full encounter with the author.

Editorial sensibility and technological strictures weigh heavily on this new edition, and are perhaps nowhere so evident as in Erdman’s treatment of The Four Zoas—especially Night VII, which provides also the single most radical editorial change from the old E. The problems here are exceedingly complex, and in some ways might be considered exemplary: a history of editorial approaches to Night VII alone could provide a useful study of the ways in which Blake’s text has been processed and disseminated. There are too many approaches to describe them all in the space of this review, but readers who need a fuller sense of the issues involved should begin page 14 | ↑ back to top consult Blake 46 (Summer 1978), which contains studies of the Night VII problem by John Kilgore, Andrew Lincoln, Mark Lefebvre and Erdman, and which provides indispensable aid for a full understanding of what Erdman calls his “drastic rearrangement” of Night VII.

The problem, of course, is that Blake left two Nights titled “Night the Seventh,” and no fully reliable clues to their probable order or priority; the editor’s task is to find ways to present them in print. Erdman’s earlier solution had what was called VIIa (ms pp. 77-90) written “later than and presumably to replace” VIIb (ms pp. 91-98); VIIa was printed between VI and VIII, and VIIb left as a kind of appendix after IX. Erdman’s decision reflected a wide tendency in the past generation of Blake scholarship to treat VIIa and VIIb as units, a practice which made it impossible to fit either or both into the text in a narratively coherent way. Of course narrative coherence in The Four Zoas is generally problematic and, insofar as one understands coherence in anything like the terms of linear logic or “realist” novels, a false issue.

The textual studies of Kilgore, Lincoln and Lefebvre made it possible to redefine the problem: VIIa and VIIb were no longer described as units but as sets of two which could be reshuffled in at least three ways.24↤ 24 Kilgore, however, believes that previous editions were “undoubtedly correct in presenting each Night as a unit, rather than attempting to reintegrate VIIb into VIIa or VII or both, for such an attempt would be highly presumptuous, and would obscure a problem it could not solve” (p. 112, emphasis added). Our own argument, it will be seen, moves along somewhat similar lines. Erdman’s textual note is a handy summary of the choices:

Andrew Lincoln, arguing from an impressive hypothetical reconstruction of the evolution of the ms, would insert VIIa between the two portions of VIIb (as Blake rearranged them). Mark Lefebvre and John Kilgore, arguing mainly from fit, propose inserting all of VIIb between the two portions of VIIa (taking the first portion of VIIa as concluding with 85:22, originally followed by “End of the Seventh Night”). Kilgore would return the transposed parts of VIIb to their original order; Lefebvre would keep them in the order of Blake’s transposing. In the present edition I have decided to follow the latter course. (E 836)Erdman does not fully explain here why he prefers Lefebvre’s theory, but from his article in Blake 46, with its fascinating system of notation, it would seem that he does so on the basis of best possible fit. But the concern with fit is itself problematic. As Erdman himself reminds us, when Ellis and Yeats first “discovered” the manuscript it was unbound, entirely a pile of loose leaves. In other words, to conceive VIIa and VIIb as either single or bipartite units is highly speculative. In The Four Zoas in general, unity is not a priori but the result of interpretive and/or editorial theory.

To call unity theoretical is not to say that it is wrong, but that it does require us to examine the theory more closely—a difficult task, since many decisions are not based on strict textual evidence but on inadequately articulated assumptions of, or desires for, a unity beyond the manuscript’s actual state. These assumptions and desires are frustrated by what appear to be conflicting notions of poetic unity in the poem itself. It is likely, and often suggested, that Blake’s difficulties in completing the Zoas arose from changes during its composition in his own sense of appropriate unity, that the poem represents a series of transformations leading from the never-ordinary narratives of the Lambeth books to the even more radical procedures of Jerusalem. The manuscript evidence of such transformations has led many readers to consign The Four Zoas to the category of brilliant failures.

The point is crucial, for what the manuscript exhibits in the most graphologically explicit fashion is an ongoing, unfinished process of self-editing, a process which print ordinarily shuts down. The process would be even more evident in the manuscript had not its keepers in London deemed it necessary to bind the leaves. This should be restated: the manuscript’s editor must be responsible to the phenomenological closures of print, but this is not to say that Blake’s editors always seek unity like that of the most ideally ordered classical epic. Rather, the editor seeks unity by attempting to extend the interrupted trajectory of Blake’s compositional process in such a way as to create a “Blakean” unity, in this case in order to salvage both Nights VII and approach a hypothetically Blakean conclusion of this infamously unfinished poem. One could describe this procedure as an editorial version of the intentional fallacy: a compositional fallacy, perhaps, or at least a compositional fiction. Passages like the following one from John Kilgore—who, as Erdman says, is concerned mostly with “fit”—are virtually standard in editorial commentaries:

It is as if Blake could not content himself with completing The Four Zoas as such, but had to go on to attempt a wholesale demonstration of the poem’s consistency with its offspring; as if, after a certain point, everything had to be said over again from the standpoint of Jerusalem. Nights I and II contain certain late additions which suggest that Blake may have decided to work through his six Nights yet again, installing passages which would anticipate the new vision, before tackling the problem of VIIb. Yet at the same time, judging by the virtually atemporal structures of Milton and Jerusalem, Blake was undergoing a crisis of disenchantment with narrative itself . . . .We have selected this passage from Kilgore (p. 112) not because he is the worst offender, merely the handiest practitioner of the compositional fiction. In fact, with his rhetoric of “as if” and “may have decided,” Kilgore’s speculations are a great deal more modest and palatable than the assertive certainties of several other commentators.

Would it be such apostasy to say that none of this matters, or that it matters only because unities we more or less subliminally associate with printed editions, with print itself, demand that it matters? The plain fact is that this Night VII is not Blake but Erdman “on” Blake; but however obvious this fact is, Erdman on Blake will tend to be read and taught as Blake. If Night VII reads more easily as narrative in new E than it did in old E; if the reshuffling of the two Nights VII better accommodates certain links between VI and VIIa1 and VIIa2 and VIII by inserting a transposed VIIb between them; if this “drastic rearrangement” more closely approximates a coherent theory of Blake’s intention or at least one probable arc of that intention, in another sense the gains of new E are also a loss, for it even more effectively obscures the nature begin page 15 | ↑ back to top of the text as manuscript, its writing of still-latent choices, its graphological, poetic uncertainties. If Erdman has produced a more accessible version—accessible in the double and related senses of wide availability and surface coherence—we must also ask what has been lost.25↤ 25 In a similar light, the practical value of Erdman’s “Editorial Rearrangement” of “Auguties of Innocence,” retained in this edition, might be less in its treatment of the poem than as a vivid synecdochic reminder of a more general editorial presence. Consider, for a minute particular, the following passage from Night the Seventh:

the howling MelancholyLike other editors, Erdman emends 95.3, but a consideration of what sense that alteration is designed to save offers tangible evidence of Blake’s manner of expanding a line’s reference. Do the daughters see “Mourning” rather than a more violent “howling Melancholy”? or “Mourning” rather than “death & torment”? If the daughters themselves, through inverted predication, are “Mourning,” what did they see, and how are they able, a few lines later, to wait “with patience” and to sing “comfortable notes”? Perhaps the daughters see a morning that lightens the horrid sight of “black melancholy.” If critics are correct in feeling that the passage calls for emendation, it seems more likely—since the text offers a situation “when Morn shall blood renew” (93.19)—that “Morning the daughters of Beulah saw [not?] nor could they have sustaind/The horrid sight of death & torment.”

For far & wide she stretchd thro all the worlds of Urizens journey

And was Ajoind to Beulah as the Polypus to the Rock

Mo[u]rning the daughters of Beulah saw nor could they have sustained

The horrid sight of death & torment But the Eternal Promise

They wrote on all their tombs & pillars

(94.55-95.5, E 367)

Surely Blake must have wished to “finish” The Four Zoas, whatever that finishing might have turned out to mean, but at the same time the very strangeness of the manuscript fascinates us: its surface chaos, its false starts, its palimpsestuous revisions and deletions are invitations to a kind of labor which is itself deleted from the print edition. Erdman prevents his reader from enjoying the difficult pleasures he himself experienced; the reader’s participation at certain graphological levels is itself edited out because the editor assumes, and must assume, that such participation is inessential to reading. To correct the graphic traces of a struggle for resurrection to unity is to assume that they are irrelevant to the reader’s experience of the text as a struggle in writing, an energetic exertion of talent including a potential grammar of mistakes which might advance reading.26↤ 26 The phrase, “grammar of mistakes,” is from Henri Frei, cited by Roland Barthes in his essay on “Flaubert and the Sentence,” in New Critical Essays, tr. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1980), p. 71. And what if the manuscript’s unfinished form is somehow appropriate to the unfinished world it explores? By resurrecting the manuscript to an editorial unity, the editor interferes with the reader’s capacity for taking the manuscript as a call for and challenge to unity on other levels. Of course this disruption cannot be total, since most of the text’s disruptions remain, so to speak, intact. If The Four Zoas as manuscript is not yet resurrected to unity, neither are the Zoas themselves; and it is perhaps a probing recognition of the strangely discordant harmony of graphological form and spiritual content which will produce the richest readings. Perhaps our best hope as readers of The Four Zoas is still to find a copy of the Bentley facsimile and apply a razor to its binding, or to wait for the promised edition (“made from infra-red photographs”) being prepared by Erdman and Cettina Magno.