review

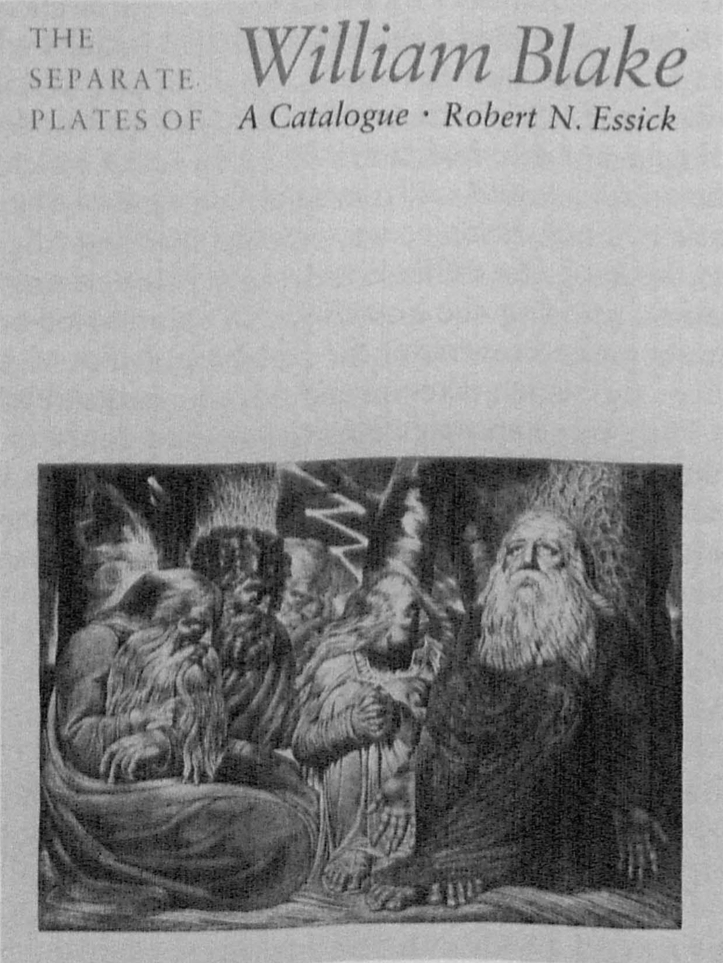

Robert N. Essick. The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1983. 302 pp., 114 illus. $75.00.

It is a little difficult to pinpoint the market at which this handsomely produced volume is aimed. All institutions who own prints by William Blake will need it as a standard reference work, but these are not many; for the layman, interested in Blake, but neither the happy owner of one of his separate plates nor a scholar to whose interest Blake studies is central, Bindman’s begin page 65 | ↑ back to top The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake is more likely to find a place upon his library shelf. This is a less comprehensive account of the minutiae of theories and analyses of the various states, known or suggested by Essick, but it is very much cheaper, and, with the illustrations integrated into the body of the text easier to handle.

Essick is a scholar of the comprehensive kind. In the tradition of G.E. Bentley, Jr. he has attempted an exhaustive study of his chosen field, which is admirable where the evidence and material is small but becomes confused and confusing when, as with Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims (XVI) his list of untraced impressions runs to 142, some of which he admits “are no doubt the same as the traced prints, and there are in all probability other extant impressions not recorded here in either category” (75). After wading through the description of the 142 items one is tempted to ask what is the point of the exercise, unless to show how careful Essick has been to incorporate everything he knows into his text lest some eager reviewer points out something which has escaped him. This may sound unnecessarily tart, but this reviewer feels it sufficient to list examples in public collections only, except where a unique state is in the private domain.

To an Englishman there are always some problems of different nuance of meaning when reading an American book. Essick’s style, in accordance with the high seriousness with which he treats his subject, is measured and a little ponderous, but not obscure or difficult to read. A few things confused me. In his description of Charity (II), he uses the technical description “planographic transfer print,” a term which usually implies the lithographic process, whereas this looks much more like a “monotype,” as Essick admits in the text. A similar confusion arises in his description of the making of the large color monotypes, worked up by hand, in his introduction, p. xxv. But on the whole Essick is accurate and intelligible in his description of the processes of printmaking and his introduction is well balanced and interesting. The main text is clear and for the most part he avoids subjective judgments, a major pitfall in Blake studies. One comment with which I had to take exception is Essick’s description of the reworking of the Job and Ezekiel prints: “Job’s heavy burden is underscored by the thick cross hatching defining his covering. The more delicate lines of ‘Ezekiel’ follow the flowing contours of garments and the burnished areas suggest enlightenment rather than oppression” (23). but on the whole this book is remarkably free of such attempts at interpretation.

Under Albion Rose (VII), as it is impossible to see the first state in an intaglio impression, is it not possible that the Huntington Library impression is a 2nd state with the “bat-winged moth” burnished out, or that Essick’s state 1 should be state 2 in accordance with the evidence of The Accusers of Theft Adultery Murder (VIII) and that there was an earlier “hypothetical” state 1, no examples of which have yet been found? To suggest this may sound perverse—after all, just because Blake produced a preliminary pull of one print does not prove that this was his invariable practice. Whilst conceding that in some instances it is likely that there were trial “states” which have not survived—the plates after Morland, The Idle Laundress (XXX) and Industrious Cottager (XXXI), are cases in point—to presuppose them and list them as hypothetical states is hedging one’s bets a bit. Better to have made an aside, suggesting that there may have been an additional state rather than boldly to list one.

In a work which is in so many ways so admirable and accurate, it is a little disconcerting to read with reference to the Butts, “Under these circumstances it is impossible to disentangle the father’s work from the son’s. Fortunately this quandary is of little consequence: the important issue is to determine the extent of Blake’s involvement in the Butts family’s graphic activities” (211). This may put the viewpoint of the Blake scholar, but the art historian is every bit as involved in ascertaining which Butts, father or son, is responsible for which print. To uncover the truth is after all our aim and responsibility. Christ Trampling on Satan (XLIV) seems to this reviewer to owe rather more to Blake in its handling than Essick allows, nor does it seem logical to dismiss his participation in the Lear and Cordelia plate (XLV), and both of the odd plates of afflicted children, Two Afflicted Children (XLVI) and Two Views of an Afflicted Child (XLVII), can only, in the light of their relationship in draughtsmanship to the series of imaginary heads, be attributed to Blake himself.

The book is extremely well produced: the print clear and the paper of high quality. There are remarkably few errors of proofreading. It should be noted that the Industrious Cottager (165) is no. XXXI; on p. 146, C, the owner is the Ashmolean Museum, and on p. 230 an unnecessary “d” is attached to the word “once” (paragraph 2, line 8). The color plates are a little disappointing, but Blake’s color is so intense and vivid that it is almost impossible to reproduce. It would have been useful to have had the ownership of the items reproduced listed below each illustration as well as in the acknowledgments.

Comments: The dating of Blake’s prints is not easy. On the whole Essick’s conclusions seem to be justified, although Erdman’s “left-pointing serif” hypothesis (see The Accusers [VIII]) is by no means conclusive.

Edward & Elenor (IV): Bindman’s date of late 1770s or early 1780s makes sense.

The Chaining of Orc (XVII): From the reproduction the date appears to be 1813.

begin page 66 | ↑ back to topRev. John Caspar Lavater (XXIX): Bindman’s suggestion that this was intended as a frontispiece to Lavater’s Physiognomy is attractive.

Industrious Cottager (XXXI): Is the child female? Untraced impressions 6. Essick’s observation is undoubtedly correct.

Falsa ad Coelum (XXXIV): Schiff’s rejection of “Ganesa” as a type for the elephant and his proposal of the phallic symbolism of the trunk and the pun on elephant are plausible.

An Estuary with Figures in a Boat (XXXV): Although it cannot be established that this relates to the sketching party on the Medway taken by Blake, Stothard and Mr. Ogleby, Bindman’s dating of c. 1780 is preferable in terms both of composition and coloring to 1790-94.

Edmund Pitts, Esqr. (XXXVI): Much more probable that “Armig” was added after Earle’s knighthood in 1802, even if it counters the “left-pointing serif” theory.

Addenda:

The Pierpont Morgan Library now owns Head of a Damned Soul in Dante’s Inferno (XXXII, 1E; given by Charles Ryskamp). The British Museum owns the unique state of Mirth (XVIII, 2; allocated by Her Majesty’s Treasury).

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, has been allocated the following items by Her Majesty’s Treasury, through the Minister of the Arts, accepted in lieu of capital taxes from the estate of the late Sir Geoffrey Keynes: Joseph of Arimathea Among the Rocks of Albion (I, 1A, 2E, 2F); The Accusers of Theft Adultery Murder (VIII, 3F); Enoch (XV, 1C); Laocoön (XIX, 1A); The Man Sweeping the Interpreter’s Parlour (XX, 2H); George Cumberland’s Card (XXI, 1N, 1O, 1P, 1Q); Morning Amusement (XXII, 1B, 1C); The Fall of Rosamond (XXV, 1A, 2C); Zephyrus and Flora (XXVI, 1A, 1B, F); Calisto (XXVII, 2C, 2D, F); Venus dissuades Adonis from Hunting (XVIII, 2A, 2B); Rev. John Caspar Lavater (XXIX, 2B, 3J, 3K); The Idle Laundress (XXX, 2C, 3E, 3F); Industrious Cottager (XXXI, 3D, 4G, 4H); Head of a Damned Soul in Dante’s Inferno (XXXII, 1D); An Estuary with Figures in a Boat (XXXV); The Child of Nature (XXXVIII, 1B, 1C); James Upton (XL, 2C); Mrs Q. (XLII, 2E); Wilson Lowry (XLIII, 2B, 3D, 3E, 4J); Bust and large wings of an angel looking to the left (Part 3, a); Centaur in a landscape with a Lapith on his back (Part 3, b); Classical figure seated on a pedestal and holding a lyre (Part 3, c); Head of a Saint (Part 3, d); Satyr with a dancing figure (Part 3, e); Christ Trampling on Satan (XLIV, 1K); Lear and Cordelia (XLV, 3C, 4E); Two Afflicted Children (XLVI); Two Views of an Afflicted Child (XLVII); Coin of Nebuchadnezzar and Head of Cancer (LVII).

The following items, which are the property of the Keynes Family Trust, are on deposit at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: Job V, 1A); Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims (XVI, 2B, 3O); The Ancient of Days (LXVII). This last item does not appear to be a print at all. Under 7 × magnification there was no evidence of a printed line, nor does it appear to have been produced by a lithographic process. The underlying image may have been reproduced by a mechanical process, but the watercolor is applied by hand. The support is card, which is unusual in Blake’s work, and Essick’s hypothesis that this is some sort of facsimile is probably correct.