discussion

Hilton Under the Hill: Other Dreamers

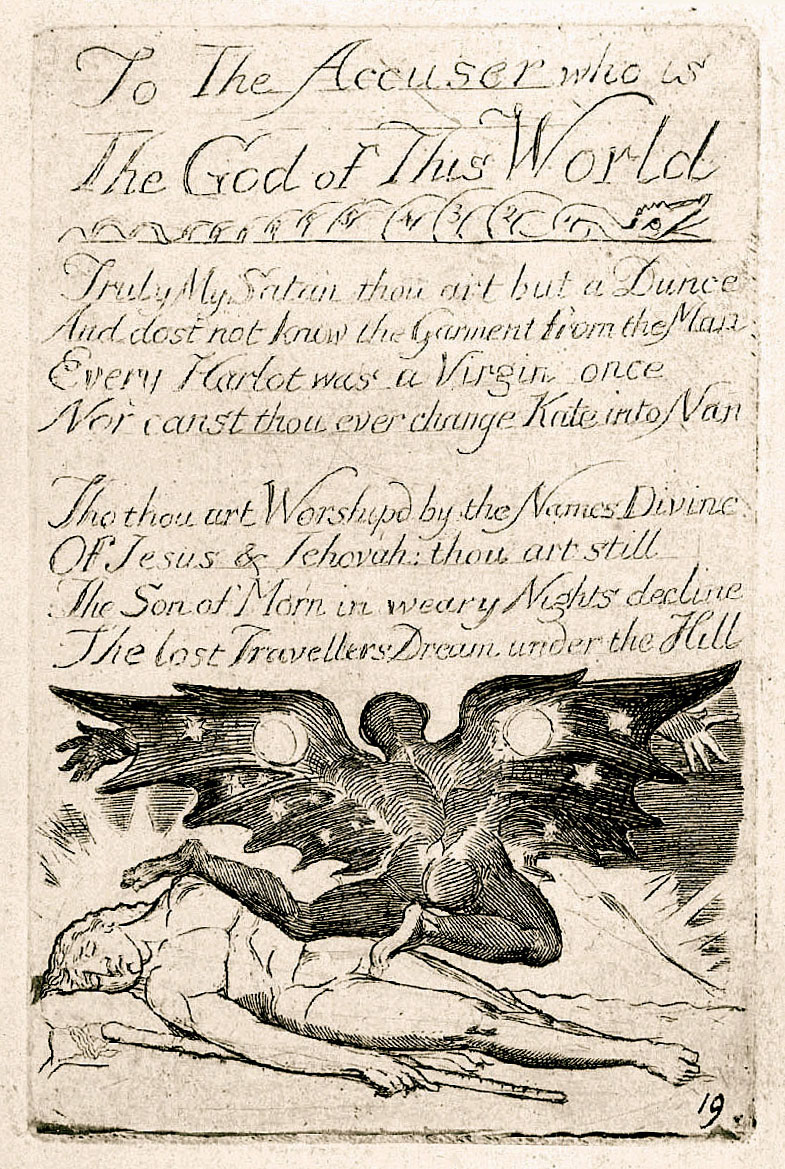

Nelson Hilton identifies the “Hill” in the last line of Blake’s “To The Accuser who is The God of This World” as Sinai.1↤ 1 Blake 22 (1988): 16-17. I see at present no reason to quarrel with this identification, though I would consider it a secondary implication, preferring the idea of a folktale allusion mentioned by Stevenson in his edition.2↤ 2 Blake: The Complete Poems (London, 1971) 845. My quarrel is rather with the misplaced ingenuity of Hilton’s methodology. It is not merely that he appears to be a kind of Jacob Bryant redivivus in his etymological speculations, whereby Hillel (the Hebrew for Lucifer) becomes “the Hill” (via the Hebrew har’el or “mountain of God”)—there is, after all nothing anachronistic about such fantasizing—but that he finds it necessary to draw upon Tyndale as the principal justification for his speculative flight, which seems exceptionable.

Hilton uses what I can only call bullying rhetoric (“does anyone imagine Blake limiting himself to ‘the Authorized Version’?”) to thrust Tyndale before our noses. It is therefore necessary to insist that, whereas no one to my knowledge ever believed that Blake limited himself to the Authorized Version of the Bible, Hilton has given us no convincing reason for supposing that he ever read Tyndale (especially with such attention as is implied in Hilton’s argument). For one thing, Hilton himself concedes that the AV refers to Moses building “an altar under the hill” in Exodus 24:4, so that the other usages in Tyndale are redundant; in addition, Blake had a more familiar source at hand; Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. (It is always better to check the familiar sources before researching the esoteric possibilities.)

It will be remembered that when Christian is directed by Mr. Worldly-Wiseman to Mr. Legality for help with his begin page 202 | ↑ back to top burden, he is asked (in parody of Evangelist’s references to the Wicket-gate and “yonder shining light”), “Do you see yonder high hill?” This hill is identified in the margin of early editions as Mount Sinai. The scene is also drawn in a woodcut, showing Christian with his burden and a staff standing with Mr. Worldly-Wiseman directly under a rocky hill, from the top of which flames and clouds redound. Christian, however, finds it impossible to proceed, because the hill terrifies him:

behold, when he was got now hard by the Hill, it seemed so high, and also that side of it that was next the way side, did hang so much over, that Christian was afraid to venture further, lest the Hill should fall on his head . . . There came also flashes of fire out of the Hill, that made Christian afraid that he should be burned: here therefore he swet, and did quake for fear.Do I therefore propsoe that Bunyan, not Tyndale, has provided the source for Blake’s “Hill”? By no means, because the Bunyan reference turns out to be confusing. For one thing, Blake’s dreamer is not “clothed in rags” and bears no burden. Second, the principal dreamer of The Pilgrim’s Progress is the narrator, the Bunyan figure familiar, perhaps, to Blake from the frontispieces. Third, the Sinai episode is not the only “underhill” experience suffered by Christian: we might equally consider his encounter with Apollyon (a ready substitute for Blake’s Spectre) in the Valley of Humiliation (but there, Christian is clothed with armor). Besides this, Christian sleeps, this time part way up the Hill Difficulty, in the arbor episode (Frye has actually proposed this as the “specific allusion”3↤ 3 See The Stubborn Structure (London, 1970) 194. ; he is also concerned elsewhere with the problem of sleeping (as in the Enchanted Ground), although actual dreaming within the dream story is reserved to the journey of Christiana. All I can say is that these hints are more suggestive than those of the Tyndale proposal and Christian is a more plausible subject for Blake’s dreamer than Moses. Hilton associates the dreamer with “Moses and his rod” but a rod is an insufficient mark of Moses, being more usually associated with Aaron, despite the important Red Sea and waters of Meribah episodes. Besides, Blake’s dreamer is simply too young to be a plausible Moses figure.

These predominantly negative remarks might be sufficient if I were content merely to rebuke Nelson Hilton, heaping coals of fire upon his head by turning back upon him his argumentum ad hominem and suggesting that he is basically too intelligent to wish to appear as one of those critics whose goal is to turn back the clock and make Blake scholarship once again a safe place for anarchists or erudite dunces. However, there is a better subject to hand, and Hilton has already provided it, in his note on “Some Sexual Connotations.”4↤ 4 Blake 16 (1982-83): 169.

Whoever else he may be, the sleeper is principally Albion, from whose loins the Spectre “Tore forth in all the pomp of War!” (J 27.37-39). Hilton has drawn our attention to the curious simulacrum (or “multistable image”) effect of the drawing, whereby the sleeper’s erect penis becomes the Spectre’s right foot; what he has not sufficiently done is to show that the Spectre himself appears to be only a kind of window through which the viewer looks at the sun, moon, and stars. (Nevertheless, Hilton does employ the suggestive—and just—phrase to describe this “nocturnal emission” or “emanation,” in relation to “The lost Travellers Dream under the Hill”: he calls it “his dream of the starry universe of generation.”) What remains is to pull together the idea of an erotic dream with that of the rampant Spectre “in all the pomp of War!” perceived as a night sky, and that of the emanation: usually Spectre and Emanation are seen as divisions of the personality, here they are conjoined in one image.

The moment depicted in this Gates of Paradise illustration is that when “the Starry Heavens are fled from the mighty limbs of Albion” (J 75.27; cf. M 6.23-25; J 27.16 [note the close context with the idea of the Spectre’s break-out from the loins]; J 30[34]20-21 [the questioning of Vala as Nature]; J 70.32 [the evocation of the “Heavenly Canaan / As the Substance is to the Shadow” as a contrary to the Vala-Rahab dominion]). This moment is usually found in the past, although in J 75 it is “now,” as indeed it is in the context of “To The Accuser” (“thou are still / The Son of Morn in weary Nights decline”). Within “The Keys of the Gates,” we are encouraged to juxtapose the image of the Spectre-night sky with that in the lines accompanying the first design (that of the woman gathering mandrakes):

My Eternal Man set in ReposeThis “key” brings to the composition the Genesis story of the creation and temptation of Eve, with a serpent reasoning under the tree of the knowledge of good and evil to set alongside “The lost Travellers Dream under the Hill” (the Tree was prohibited; the Hill, if it be Sinai, is the place where the Law begin page 203 | ↑ back to top prohibiting desire itself was written). We infer that in the Eternal Man’s sleep the whole created world was embodied as an object of desire (an emanation) and simultaneously as a mode of dominion. As Blake observed elsewhere, “The desire of Man being Infinite the possession is Infinite & himself Infinite” (No Natural Religion [b], 7); he also remarked that “hell is the being shut up in the possession of corporeal desires which shortly weary the man for all life is holy” (Annotations to Lavater 309; the use of the word “weary” is notable in anticipation of the later poem).

The Female from his darkness rose

And She found me beneath a Tree

A Mandrake & in her Veil hid me

Serpent Reasonings us entice

Of Good & Evil: Virtue & Vice

The spectrous dream emanation is a brilliantly conceived figure in illustration of a poem which defines its subject as one who does not know “the Garment from the Man,” in that it is simultaneously naked (it has no garment) and wears only a garment (it is “clad” with the starry universe), or rather a veil (it is a dark vision of the universe, which is only a shadow of Eternity). The paradoxical irony is that Albion’s Emanation, Jerusalem, and Spectre (who might be subsumed for the sake of this exposition under all of the Zoas) are embodied within him, but it is by turning them into prohibited objects of desire and predatory desiring subjects that he ceases actively to enjoy them and becomes their victim.

To set out all of this more fully would not only require a detailed exposition of the “Keys of the Gates” (within which are the lines on another figure of the Spectre, for emblem 5, and ones on true vision—of “The Immortal Man that cannot die,” for emblem 13), but also a detailed exposition of, at least, much of Milton (including plates 18 and 42) and Jerusalem, especially plate 27, and even of more remote works such as The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, “Introduction” to Songs of Experience, “To Tirzah,” and “The Everlasting Gospel.” This is not the place for such a strenuous exercise. Perhaps I should additionally note that the rod held by the sleeper is the emblem of his authentic power (“That might controll, / The starry pole”), which is, however, to be used actively in mental warfare, not fondled during sleep. Also, the form of the Spectre is related to that of Time considered as lost opportunity (cf. NT 46): the expression of Time in the figure is as important as that of Space; that such other designs as “The Good and Evil Angels” color print, and the “Great Red Dragon” pictures (especially the one in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.5↤ 5 Martin Butlin, The Drawings and Paintings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1981) illus. 400, 519, 520. ), are closely relevant—indeed, once one starts this sort of thing, one never knows where to stop!

What most impresses me about the poem, “To The Accuser who is The God of This World,” is the quiet tone with which such tremendous and resounding truths are uttered. Behind them is the force of the struggles of a lifetime and they reflect the poet-prophet’s own weariness. Edward Young, as Stevenson has noted, had “dared” to call Satan a dunce (Night Thoughts 8.1347, and Blake’s illustration, NT 416, shows Satan trying to tell “the Garment from the Man” by testing Jesus with stones for making bread). Blake calls the Accuser, familiarly, “My Satan,” as if he were his own foolish child. Furthermore, Blake concedes that Satan is, indeed, “the Son of Morn,” using, as Hilton also noted, the language of Isaiah 14:12. (E. J. Rose has made a few helpful comments on this.6↤ 6 “To The Accuser who is The God of This World” Explicator 22 (1964): 37. For Rose, however, the Hill is the mound-mount of Golgotha-Calvary and the dreamer is in the grave: “The traveler is lost because he cannot reach the true God; instead he dreams the sleep of death, the life of this world. The Gates of Paradise are closed.”) The trouble is that Lucifer is out of place, not the lark singing of dawn, not the light-bearer, but the bearer, indeed, the wearer (the wear-weary pun is surely one which would appeal to Hilton) of darkness. (There is another possible pun, on traveler and travailer, as the sleeper gives birth in the manner of Satan conceiving Sin.)

Finally, why is the folklore dreamer and not Moses to be considered as the primary analogue for sleeping Albion? I believe this is because we are to think first of the dream as one of erotic desire. Mount Sinai can be accommodated to that idea only after the reader has established the nexus between desire and punishment, through linking the text and design with the Genesis, Exodus, and Isaiah allusions mentioned above. This desire may be articulated as a desire for Jerusalem, for lost freedom (for a time when one was lost but freely at home), but insofar as one is lost, it may become perverted as a shameful “lust of possession” and so as subject to the tyrannies of separated emanation and Spectre. A capital gloss on the poem is thus to be found in the quatrain lyric of J 27, which includes the idea of “Gates”: “Entering through the Gates of Birth / And passing through the Gates of Death.” It may also be helpful to recall the epic simile in Paradise Lost 1.781-88 (which begins with a reference to “Pigmean Race / Beyond the Indian Mount”), concerning “Faerie Elves,”

Whose midnight Revels, by a Forrest sideThis allusion has the right associations in suggesting that the “Faerie Elves” have diabolic counterparts or implications. Blake appears to draw on the passage elsewhere, in “The Mental Traveller,” for the idea of the sun and stars being “nearer rolld” to the lovers who wander in the desert.

Or Fountain, some belated Peasant sees,

Or dreams he sees, while over head the Moon

Sits Arbitress, and neerer to the Earth

Wheels her pale course: they on thir mirth and dance

Intent, with jocond Music charm his ear;

At once with joy and fear his heart rebounds.