article

begin page 52 | ↑ back to topBlake’s Bald Nudes

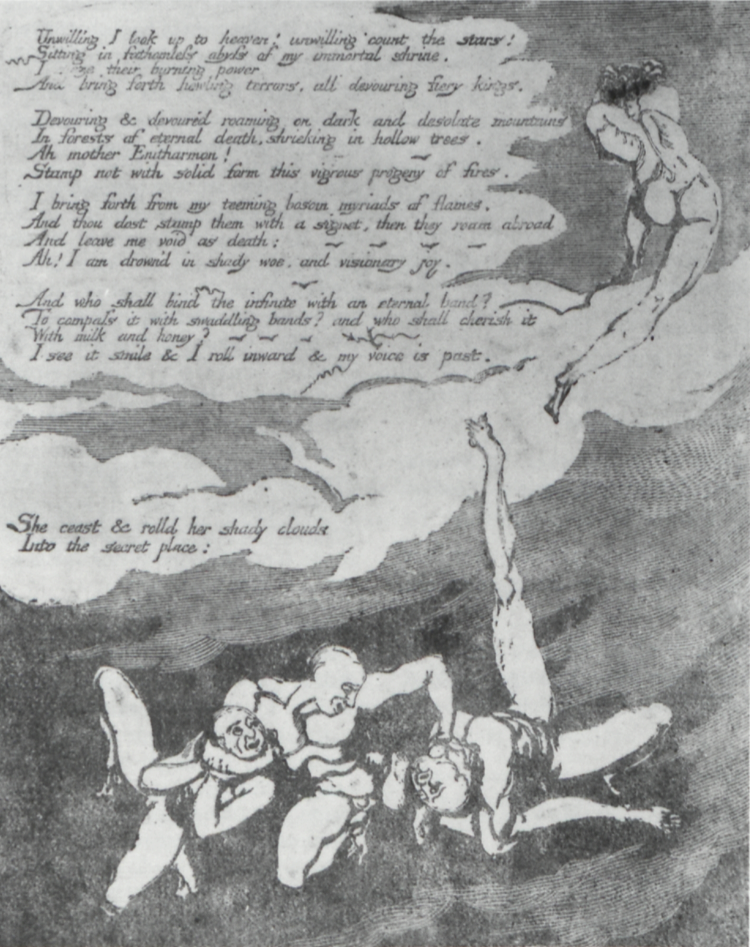

Among William Blake’s illuminated books, Europe a Prophecy draws particular attention because of the power of its designs. Plate 2, for example, is enlivened with three bald and naked combatants, plus a fourth figure grasping his hair or wig with both hands (illus. 1). Perhaps we are to imagine that he is escaping from the melee below. The central wrestler is having the best of it, for he has a headlock on one victim and is choking the other. The scene itself gives no clear clue as to why one man is treating his companions so nastily. The background suggests clouds, and thus the group would appear to be suspended in, or falling through, the sky. The text offers little help. Nothing in the poem clearly presents itself as a description of these wrestlers, although they may be among the “howling terrors” mentioned in line 4 of the plate, and the headlock and choke hold may be a cryptic answer to the question in line 13: “And who shall bind the infinite with an eternal band?”1↤ 1 See also “the terrors of strugling times” on plate 9. Plate numbers and quotations from Blake’s works are taken from The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, rev. ed. (Berkeley: U of California P, 1982). Edward Young’s “Chaos, and the Realms / Of hideous Night” are illustrated by Blake with two bald and nude wrestlers similar to those in Europe. See William Blake’s Designs to Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, ed. John E. Grant, Edward J. Rose, and Michael J. Tolley (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1980), NT 496 (Night IX, page 78). In copy D of Europe (British Museum), George Cumberland added to plate 2 verses from Richard Blackmore’s Prince Arthur: An Heroick Poem (1695), hinting that the three men are personifications of Horror, Amazement, and Despair: ↤ 2 All the lines Cumberland added in his copy of Europe are quoted, and their sources identified, in S. Foster Damon, William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols (London: Constable, 1924) 348-51. The substitution of “the convulsion” for “this convulsion” in the lines from Blackmore’s poem indicates to Damon that Cumberland was quoting from the excerpt in Edward Bysshe’s The Art of English Poetry (415 in the London 1708 ed., under the subject-heading “Storm”). It is possible, but far from certain, that Blake suggested or approved of these additions by his friend, but at the very least Cumberland seems to be working within the iconography of bald nudes discussed here.

This orb’s wide frame with the convulsion shakes,begin page 53 | ↑ back to top These apocalyptic suggestions, clearly in harmony with the general tone of Europe, are given a contemporary context in David V. Erdman’s political interpretation of the design: “Pitt [the middle figure] is stifling expressions of Horror and Amazement at his catastrophic policy but is unable to suppress the silent figure of Despair, which is ascending” top right.3↤ 3 Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, rev. ed. (Garden City: Anchor Books, 1969) 220. Erdman’s assumption that only two of the personifications in Blackmore’s poem refer to the struggling group may be correct. However, since Cumberland wrote the lines from Prince Arthur below the plate and added a passage from Samuel Garth’s The Dispensary(1699) above it, the identification of Blackmore’s three personifications with the three figures in the lower part of the plate seems more likely on the face of it. Erdman modifies this reading in The Illuminated Blake (the “strangler” may be Henry Dundas rather than Pitt; the escapee at the top may be Lord Chancellor Thurlow) and adds that “the [lower] scene recalls young Hercules strangling serpents in his cradle.” He further suggests that the baldness and nakedness of the lower figures might be explained as an indication of Hercules’ infancy (but that could account only for the strangler’s appearance) or as a pictorial literalization of Thurlow’s loss of his “judicial gown and wig” when “expelled from Pitt’s cabinet.”4↤ 4 Erdman, The Illuminated Blake (Garden City: Anchor Books, 1974) 160. This last point does not easily accommodate the identification of Thurlow as the figure top right since he retains his hair or wig. Indeed, Erdman’s specific identifications of these figures seem farfetched, although the general thesis that the iconography has a political dimension is sound.

Oft opens in the storm and often cracks.

Horror, Amazement, and Despair appear

In all the hideous forms that Mortals fear.2

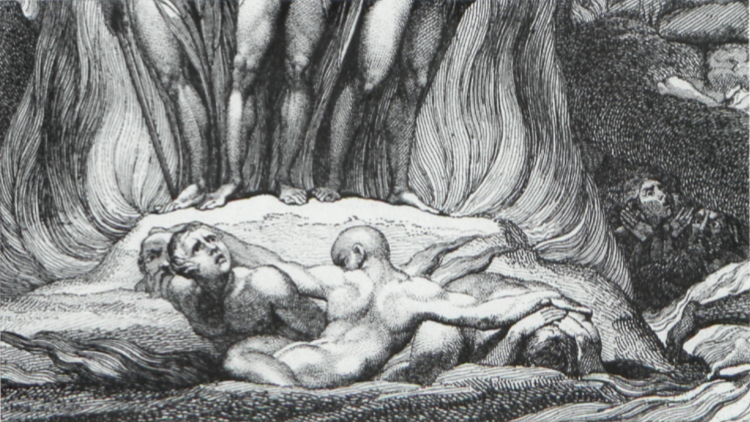

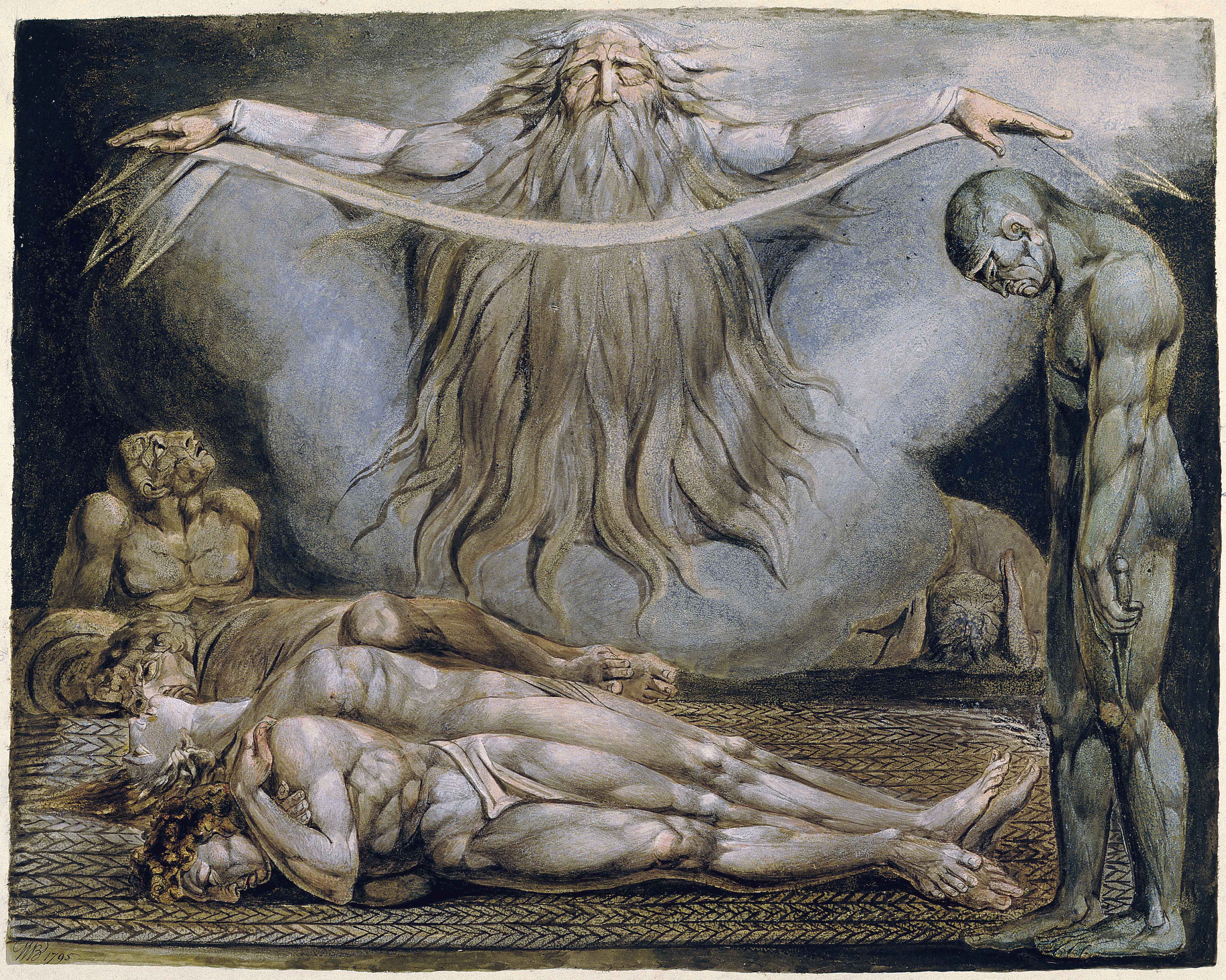

A few precedents for bald and naked figures in the pictorial arts can enrich our understanding of these motifs in Blake’s work. Perhaps the most famous example in European painting is Michelangelo’s Last Judgment fresco, completed in 1541. At least one of the damned, a prominent figure in Charon’s boat, lower right, clutching his head in despair, is bald and nearly nude (illus. 2). Blake’s knowledge of Michelangelo’s painting through reproductive engravings is virtually certain.5↤ 5 The specific engravings Blake saw have never been identified. Possible candidates include the ten detail plates by Giorgio Ghisi (mid-1540s), the nine plates by Nicolas Beatrizet (1562), and the single engravings of the entire fresco by Guilio Bonasone (c. 1546), Giovanni Baptista de’ Cavalieri (1567), and Martinus Rota (1569). George Cumberland owned an impression of Bonasone’s print—see his Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasone (London: Robinson, 1793) 61, and An Essay on the Utility of Collecting the Best Works of the Ancient Engravers of the Italian School (London: Payne and Foss et al. 1827) 310-11. For reproductions of the engravings by Cavalieri, Rota, and Bonasone, see Charles De Tolnay, Michelangelo: The Final Period (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1971) figs. 258, 259, 260b. For essays that center on Blake’s borrowings of figure types from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, see Leslie W. Tannenbaum, “Transformations of Michelangelo in William Blake’s The Book of Urizen,” Colby Library Quarterly 16 (1980): 19-50, and Irene H. Chayes, “Blake’s Ways with Art Sources: Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment,” Colby Library Quarterly 20 (1984): 60-89. Blake’s own Last Judgment design illustrating Robert Blair’s The Grave includes one such figure just above the lower margin of the image (illus. 3). Michelangelo’s figure, although completely dissimilar in posture, may have provided a precedent for Blake’s doomed soul who, much like the

Michelangelo’s bald nudes are not the first such Renaissance portrayals of the damned. Luca Signorelli’s frescoes of the Last Judgment, painted 1499-1504 begin page 54 | ↑ back to top

The unknown date of Flaxman’s designs and his absence from London until the year Blake etched on the title page to Europe make direct influence less than certain. But no such difficulty, nor the distance from London to Orvieto, attends upon a more public precedent for Blake’s bald nudes. From 1676 until 1814, Bethlehem (or “Bethlem” or “Bedlam”) Hospital for the insane stood in Moorfields, along the north side of London Wall Street (the present cite of Finsbury Circus). Over its main gate reigned two near life-size figures sculpted in Portland stone, the one on the left representing melancholy madness, and his chained companion on the right raving madness (illus. 6).8↤ 8 The identification of each figure is apparently traditional. The first printed description I have found is Colley Cibber, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber (London: for the author, 1740) 5 (quoted in Bowen’s pamphlet [5 note] discussed below). For photo reproductions of the statues removed from their pediment, see Howard Roberts, ed., Survey of London (London: London County Council, 1955) 25: plate 41. These statues, the work of Caius Gabriel Cibber (or “Cibert,” 1630-1700), were placed above the gate c. 1680 begin page 55 | ↑ back to top and were not removed until the hospital moved its quarters to Lambeth.9↤ 9 Samuel Redgrave, A Dictionary of Artists of the English School (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1874) 80. In recent years they have been kept at the Bethlem Royal Hospital, Beckenham, and the Museum of London. Both figures are bald and, although draped with small loincloths, are basically conceived as nudes.

Cibber’s madmen were among eighteenth-century London’s most famous public statues. In his attack on the sculptor’s son, Colley Cibber, in The Dunciad, Pope makes reference to “those walls where Folly holds her throne” and “Great Cibber’s brazen, brainless brothers”—that is, his father’s sculptural offspring.10↤ 10 Alexander Pope, The Dunciad, ed. James Sutherland, 3rd ed. (London: Methuen, 1963) 271. “Brazen” is a comment on Colley Cibber, but also appropriate for his “brothers” since the stone statues were stained to simulate patinated bronze. The description of the statues by Blake’s acquaintance Allan Cunningham gives some indication of their fame and impact: “Those who see them for the first time are fixed to the spot with terror and awe; an impression is made on the heart never to be removed; nor is the impression of a vulgar kind. . . I remember some eighteen or twenty years ago, when an utter stranger in London, I found myself, after much wandering, in the presence of those statues, then occupying the entrance to Moorfields.”11↤ 11 The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (London: John Murray, 1830) 3: 26-27. Flaxman makes passing reference to “the mad figures on the piers of Bedlam gates” in his Royal Academy lecture on “English Sculpture”—see his Lectures on Sculpture(London: John Murray, 1829) 30. It would have been difficult for Blake, an inveterate walker and, like Cunningham and the speaker of “London” in Songs of Experience, a fellow wanderer in London’s streets, not to have known Cibber’s statues. Blake was certainly aware of the building these statues decorated, or its successor in Lambeth, for on plate 45 [31] of Jerusalem, he refers simultaneously to the biblical town and to London’s hospital for the insane: “Bethlehem where was builded / Dens of despair in the house of bread” (E 194). A further and earlier connection with Blake’s circle of friends is established by the engraving reproduced here (illus. 6), for it is based on a drawing by Thomas Stothard of the statues and their pediment.12↤ 12 Blake knew Stothard well by no later than late in 1780—see Bentley 19. The plate was published as the frontispiece to a sixteen-page pamphlet of 1783 by Thomas Bowen, An Historical Account of the Origin, Progress, and Present State of Bethlem Hospital.13↤ 13 The last line of the inscribed verses is bound into the spine of the Huntington copy, reproduced here, but is fully revealed in a copy of the pamphlet offered by the London bookdealer C. R. Johnson, January 1990, catalogue 29, item 126, with the frontispiece reproduced. I am indebted to my colleague George Pigman for the following rough translation: “A double column raises itself at the gates of Bethlem; the stone on the outside has an image of the people within. On the right [from the perspective of the figures] a man leans his bald head with a sad face; on the left, iron chains hardly hold another man. The madness in the statues differs, but each madness praises each work and the genius of the sculptor.” These lines are quoted from Lusus Westmonasterienses [(Westminster: A. Campbell, 1730) 78], a collection of Latin verses and epigrams.

Blake’s figures in Europe do not repeat the postures of Cibber’s, but their nakedness and baldness would have united suggestions of madness to the iconography of damnation for a London artist and his London audience. The caricature-like faces of Blake’s three wrestlers add to the implications of insanity. Although Cibber’s figures are heavily indebted to Michelangelo’s Medici Tombs in posture, architectural placement, and musculature, it was widely believed that they were based on actual inmates of Bedlam. According to Horace Walpole, “one of the statues was the portrait of Oliver Cromwell’s porter, then in Bedlam.”14↤ 14 Anecdotes of Painting in England, 3rd ed. (London: J. Dodsley, 1782) 3: 146. Bowen notes that this “tradition” identified the porter with the “melancholy lunatic” on the left (5 note). Margaret Whinney, Sculpture in Britain 1530 to 1830 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964), reproduces the melancholic (pl. 36B) and comments that Cibber’s “two powerful nudes, horrifying in their realism, must surely have been studied from the life . . .” (49). Recent arrivals at the hospital may have already had their heads shaven, and their wigs taken from them, but patients may have been kept bald to control head lice and other pests. William Hogarth’s final plate in “The Rake’s Progress” series of 1735 (illus. 7) shows Tom Rakewell in Bedlam—bald (like several other inmates), wearing only breeches, insane, and being placed (like Cibber’s raving madness) in irons. The rake, and the half-naked religious fanatic on the left, may have been influenced by Cibber’s statues as much as by real patients;15↤ 15 Georg Chistoph Lichtenberg, in his commentaries on Hogarth’s engravings first published in German, 1784-96, notes that “it is said that Hogarth took the idea for that remarkable head [the baldheaded man far right] and for the one opposite in No. 54 [the religious fanatic far left] from the excellent statues above the portal leading into the courtyard of Bedlam” (quoted from Lichtenberg’s Commentaries on Hogarth’s Engravings, trans. Innes and Gustav Herdan [London: Cresset P, 1966] 268n1). but Hogarth’s engraving indicates the extent to which a paucity of clothing (the would-be monarch in the central cell is stark naked) and a bald pate undecorated by a wig were identified with madness in popular imagery.

The legend that Cibber’s melancholic was modeled on Cromwell’s porter carries us back to Erdman’s political interpretation of the scene in Europe. Perhaps the fate of the servant signifies something about the politics of the master—or even the fate of all regicides. Yet if Erdman is correct about the pictorial allusion to Pitt and his circle, the Europe 2 shifts the butt of criticism from the revolutionary to the establishment: England’s policies are not only damnable, but insane. Further political implications arise if we take the similarities between Blake’s figures and Cibber’s to be a reference

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

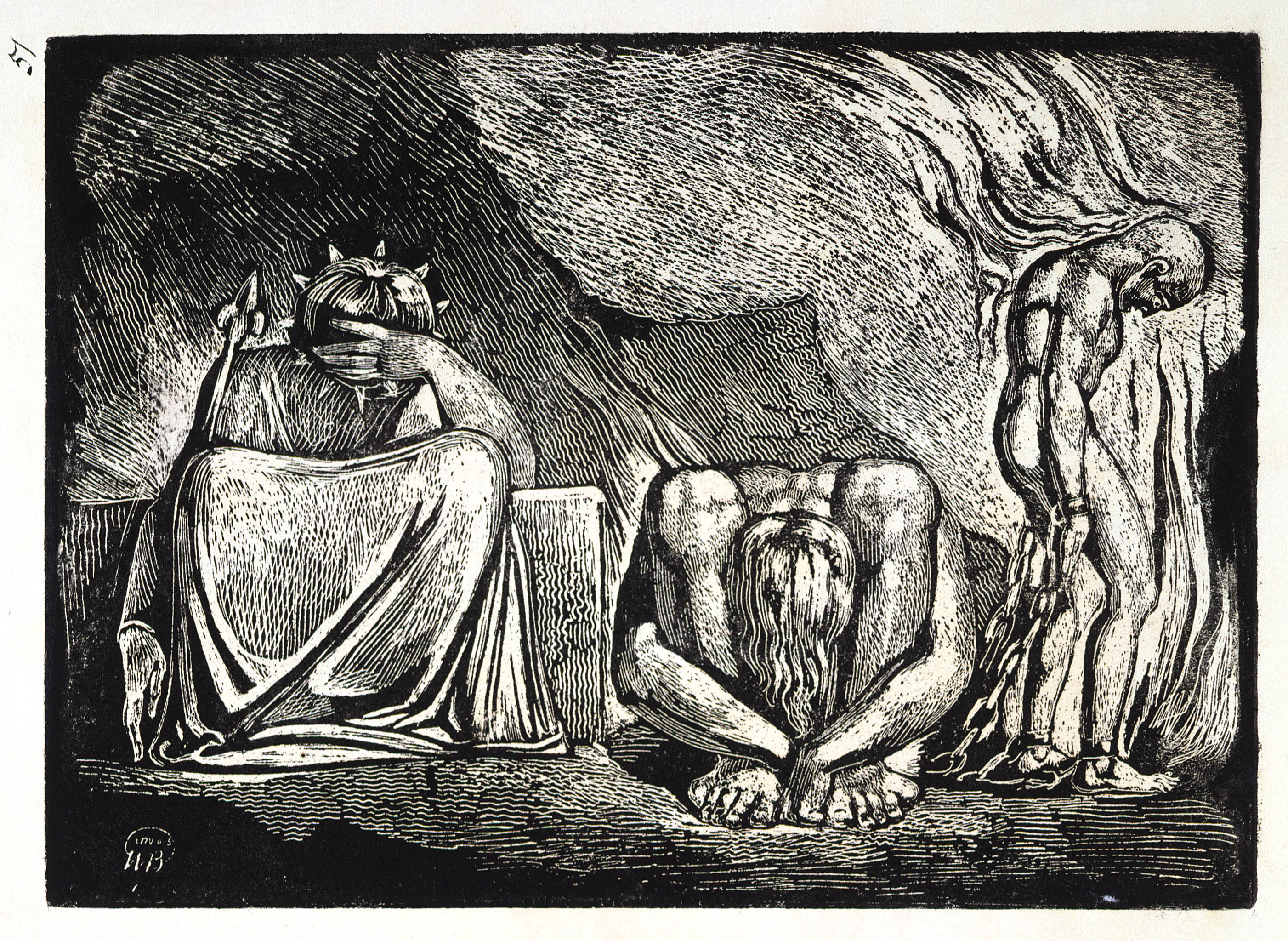

The appearance of bald nudes in two of Blake’s later designs continues the implications of insanity. In the year after Europe, Blake designed and first executed a group of color prints, including The House of Death based on Paradise Lost, bk. 11, lines 477-93 (illus. 8). Blake’s interest in Milton’s description of “A Lazar-house” may have been stimulated by the reformist efforts of John Howard, whose Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe appeared in 1789, with a second edition in 1791. Bedlam was among the hospitals Howard visited. Although he found some conditions to commend, he notes in passing that “there is no separation of the calm and quiet [inmates] from the noisy and turbulent, except those who are chained in their cells.”18↤ 18 Howard, An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe (London: J. Johnson, C. Dilly, T. Cadell, 1791) 139. Blake begin page 57 | ↑ back to top

Blake’s final rendering of a Cibberian madman slouches near the right margin of Jerusalem plate 51 (illus. 9). Although this figure is clearly developed from his predecessor in the color print (illus. 8), the absence of the knife and the addition of chains make his relationship to Cibber’s raving madness (illus. 6) more prominent. In a separate impression of plate 51 (Keynes Collection, Fitzwilliam Museum), Blake cut the word “Skofeld” in white line beneath the man on the right, thereby identifying him with the character in Blake’s late poetry based on John Scolfield, the soldier who charged Blake with sedition in 1803.22↤ 22 Paley, The Continuing City: William Blake’s Jerusalem (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1983) 217, comments that “Skofield is represented [in Jerusalem pl. 51] as either a madman (cf. Hogarth’s dying Rake) or a convict, which is what he had wanted to make Blake.” “Scofield” (the spelling changes frequently) first appears in Milton, where he is introduced as “bound in iron armour before Reubens Gate” (19.59; see also Jerusalem 11.21-22). This location makes the characteristics Skofeld’s portrait shares with Cibber’s statues above Bedlam’s gates all the more appropriate. To portray his accuser and the powers he represented as insane, Blake once again used the bald and naked imagery linked to Bedlam’s inhabitants, both sculptural and human.