MINUTE PARTICULARS

New Voice on Blake

In editing Wordsworth’s Chaucer modernizations for the Cornell Wordsworth, I came across a manuscript containing a significant piece of Blake criticism.*↤ Research for this paper was made possible by grants from the American Council of Learned Societies and the National Endowment for the Humanities. I am grateful to both for their assistance. I am also grateful to Jonathan Wordsworth and the Trustees of the Wordsworth Trust for permission to quote from the Dove Cottage Papers. Finally, I wish to thank Alexander Gourlay, Mark L. Reed, and Joseph Viscomi for their generous advice, without which the paper could not have been written. The manuscript is a fair copy review of Chaucer Modernized, 20 pages long, clearly ready for publication but apparently never published; it is preserved in the Wordsworth Library, boxed with Wordsworth’s other papers having to do with Thomas Powell and the Chaucer Modernized volume. Chaucer Modernized itself, published late in 1840, was a volume of modernizations of Chaucer’s verse organized and edited by Powell and R. H. Horne, and containing contributions from such authors as Leigh Hunt and Elizabeth Barrett. It included two works of Wordsworth: his version of the pseudoChaucerian “Cuckoo and the Nightingale,” and his extract from Troilus and Criseyde.

The author of the manuscript review is a person of sound literary judgment, who possesses a thorough knowledge of Middle English and has read carefully the commentary in Tyrrwhitt’s edition of Chaucer’s poems. We can surmise that he is a lawyer, for besides references to Blackstone’s Commentaries and trade and tariff regulations, he draws on an extensive knowledge of English law and the organization of the Inns of Court to illuminate several passages of Chaucer’s verse. It is also significant that he claims to know Wordsworth personally. He disapproves of the Chaucer Modernized project, but directs his opprobrium at the contributions of Horne and Powell, not at Wordsworth himself. Horne, the reviewer writes, “cannot even construe old poetry, still less paraphrase it.”1↤ 1 An amusing account of Horne’s difficulties in translating Chaucer may be found in Ann Blainey, The Farthing Poet: A Biography of Richard Hengist Horne, 1802-1884, A Lesser Literary Lion (London: Longman’s, 1968) 115. And he considers Powell even less competent. For Wordsworth’s contributions, he has the highest praise. He urges him to complete his version of Troilus: “It will be an amusement to his honored age, feeble only in eyesight, to dictate his translation to his amiable lady.” And of “The Cuckoo and the Nightingale,” he writes: “We bow to the Master! We only wish he had reserved it for his own next volume of Poems, and not buried it in this dunghill.”

At the very end of the review, after discussing each contributor’s efforts, the reviewer turns, as if out of the blue, to the subject of William Blake.

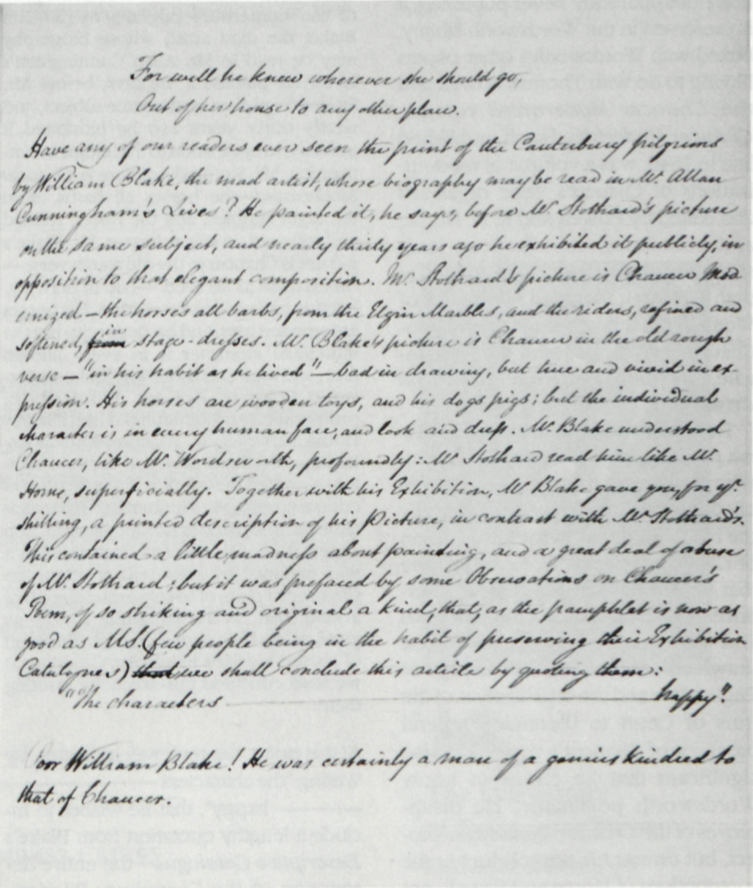

Have any of our readers ever seen the print of the Canterbury pilgrims by William Blake, the mad artist, whose biography may be read in Mr. Allan Cunningham’s Lives? He painted it, he says, before Mr. Stothard’s picture on the same subject, and nearly thirty years ago he exhibited it publicly, in opposition to that elegant composition. Mr. Stothard’s picture is Chaucer Modernized—the horses all barbs, from the Elgin Marbles, and the riders, refined and softened, in stage-dresses. Mr. Blake’s picture is Chaucer in the old rough verse—“in his habit as he lived”—bad in drawing, but true and vivid in expression. His horses are wooden toys, and his dogs pigs; but the individual character is in every human face, and look and dress. Mr. Blake understood Chaucer, like Mr. Wordsworth, profoundly. Mr. Stothard read him like Mr. Horne, superficially. Together with his Exhibition, Mr. Blake gave you, for your shilling, a printed description of his Picture, in contrast with Mr. Stothard’s. This contained a little madness about painting, and a great deal of abuse of Mr. Stothard; but it was prefaced by some Observations on Chaucer’s Poem, of so striking and original a kind, that, as the pamphlet is now as good as MS. (few people being in the habit of preserving their Exhibition Catalogues) we shall conclude this article by quoting them:At this point, the reviewer indicates, by writing “the characters—happy”, that he wishes to include a lengthy quotation from Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue—the entire description of the Canterbury Pilgrims, beginning on page 9 of the catalogue and ending on page 25. The review ends with this remark: “Poor William Blake! He was certainly a man of a genius kindred to that of Chaucer.”

This passage is remarkable not so much for the information it conveys—most of that is derived from Allan Cunningham’s biography of Blake—as for the reviewer’s lively interest in Blake and rare appreciation of his critical acumen. Although he accepts the usual characterization of Blake as a “mad artist,” he is not interested in perpetuating what Bentley calls “titillating rumors of the mad painter’s visions,” as was the rule among contemporary literary journalists.2↤ 2 G.E. Bentley, ed., Blake: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975) 220. Rather, he expresses admiration for Blake’s understanding and champions his interpretation of Chaucer. In quoting at tremendous length from the Descriptive Catalogue (which, along with a copy of Blake’s “Canterbury Pilgrims,” he apparently owned), he effectively sets Blake up as the interpreter of Chaucer that Horne was not. Also noteworthy is the analogy he draws between the roughness of Blake’s drawing and the roughness of Wordsworth’s deliberately archaic modernizations. He considers their rough crudeness truer to the genius of Chaucer than the “softened stage dresses” of Stothard on the one hand, and Horne on the other. Because of these remarkable opinions, the identity of this reviewer should be of interest to scholars of Blake and Wordsworth alike.

The candidate that comes first to mind is Henry Crabb Robinson. Robinson, of course, knew both Blake and Wordsworth, attended and wrote about Blake’s 1809-10 exhibition, owned four copies of the Descriptive Catalogue, one of which he gave to Charles Lamb, and purchased two copies of the “Canterbury Pilgrims.”3↤ 3 See Robinson’s Reminiscence of Blake in G.E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1969) 537-38. He was also a lawyer. But the arguments against his authorship are substantial. First, the reviewer speaks of the admission price to the 1809 exhibition as being one shilling. This is both inaccurate—the price was half a crown (2s.6d)—and does not square with what Robinson himself wrote in his Reminiscences ten years begin page 92 | ↑ back to top later: “a half crown was demanded of the Visitor for which he had also a Catalogue. . . .”4↤ 4 Bentley, Blake Records 537. Second, there is a problem with the spelling of the name of Blake’s rival, Stothard. In his Reminiscences, Robinson spelled this name inconsistently, either as Stodart or Stoddart. The reviewer, however, spells it correctly all five times. Third, whereas the reviewer depends on Cunningham for his account of the Stothard incident, Robinson gives a different version that is more sympathetic to Stothard, whom he calls “an amiable and excellent man.”5↤ 5 Bentley, Blake Records 537-38. Finally, and most convincingly, the handwriting in the manuscript is not Robinson’s. The review itself may have been the work of a copyist, but traces of the author’s handwriting survive; they are found on clippings from the Chaucer Modernized volume that have been pasted into the review. On these clippings, the author has written pencil corrections of Horne and Powell’s translations. These corrections do not match Robinson’s hand at all.

Crabb Robinson’s diaries help to reveal the reviewer’s identity. On 8 January 1828, Robinson records a visit he made to Blake’s widow in the company of Barron Field, a lawyer and a correspondent of Wordsworth. ↤ 6 Bentley, Blake Records 362.

Walked with Field to Mrs Blake The poor old lady was more affected than I expd yet she spoke of her husband as dying like an angel. She is the housekeeper of Linnell the painter & engraver—And at present her Services must well pay for her board—A few of her husbands works are all her property—We found that Job is Linnells property and the print of Chaucers pilgrimage hers—Therefore Field bought a proof and I two prints—@ 2- guas each—I mean one for Lamb6This means that Field, like Robinson and Lamb, owned a copy of Blake’s “Canterbury Pilgrims,” which makes him the only other person among Wordsworth’s acquaintance whom we know to have possessed one. And it would have been natural for Robinson to give him a copy of the catalogue too, to go with the proof.

Barron Field’s character and circle of acquaintance are in accord with the profile I have suggested for the author. Field, a lawyer, had published an analysis of Blackstone’s Commentaries in 1811, and as Chief Justice of Gibraltar until 1841, would have been familiar with the kinds of trade and tariff regulations discussed in the review. Moreover, Field had long been associated with major literary figures. He was a schoolmate of Leigh Hunt at Christ’s Church Hospital, and as a young man wrote reviews for Hunt’s Reflector and published poems in the Examiner. Field met Wordsworth as early as 1812, and Robinson and Lamb were lifelong

friends.7↤ 7 See Geoffrey Little’s biographical introduction to his edition of Field’s Memoirs of Wordsworth (Sydney: Sydney UP, 1975) 7-17. In fact, he is mentioned in two of the Elia essays, including “Distant Correspondents,” which is addressed entirely to Field, who was then living in Australia. His friendship with Lamb is especially significant because he echoes Lamb’s opinion about Blake’s Chaucer criticism: “Lamb,” recalled Robinson, “. . . declared that Blake’s description [of the Canterbury pilgrims] was the finest criticism he had ever read of Chaucer’s poem.”8↤ 8 Bentley, Blake Records 538. Wordsworthians know Field primarily as the author of a memoir of the poet, completed in 1840 but not published because of Wordsworth’s objections, and there survives a series of letters between the two, in which begin page 93 | ↑ back to top Field criticized the ways Wordsworth had revised his poems and urged him (often successfully) to change them back. Field, in fact, kept an annotated copy of Wordsworth’s collected poems, in which he recorded all of the poet’s alterations in the published versions of his poetry,9↤ 9 This copy can be found in the Wordsworth Library in Grasmere. and he joked with Wordsworth about having “the honour to be your Editor. ‘The fifteenth Edition, with Notes by Barron Field.’”10↤ 10 Barron Field to Wordsworth, 10 April 1828, published in Little 133. The manuscript is in the Wordsworth Library. Furthermore, a comparison of handwritings confirms Field’s authorship.Fortunately, we can trace Field’s interest in the Chaucer Modernized volume with some exactness. In the early months of 1840, shortly after completing his memoir of Wordsworth, Field visited England and called at Rydal Mount. No doubt the main subject discussed during the visit was the memoir, whose publication Wordsworth had resisted. But Wordsworth was also preparing to publish his modernizations of Chaucer in Horne and Powell’s volume and had a long discussion with Field about doing so. In a paragraph added to the memoir after 1841, Field tells how

the Poet . . . read to me . . . his Lines of hearing the Cuckoo at the Monastery of San Francisco d’Assisi, and his modernization of Chaucer’s Cuckow & Nightingale. . . . [I]n illustration of the latter he referred to the part the Crow plays in the Manciple’s Tale, and praised the father-poet’s dramatic skill and courage, in making the Manciple, whose only object in life was to be a trusty domestic, draw this moral alone from the story:—Field then tells how Wordsworth “threw his Cuckow and Nightingale into a bad collection of pieces entitled ‘Chaucer Modernized.’”11↤ 11 Little 49. These remarks correspond closely to two passages in the review. In the first paragraph, Field writes that “Mr. Wordsworth . . . is so warm an admirer of [“The Manciple’s Tale”], that we have heard him lament the impossibility of translating the whole.” Then, at the end of his discussion of Leigh Hunt’s “emasculated” version of the tale, we find the following:

My sone, beware, and be non auctour newe

Of tidings, whether they ben false or trewe:

Wher so thou come, amonges high or lowe,

Kepe well thy tonge, and thinke upon the Crowe

He wished that the delicacy of modern ears would allow him to translate the whole of this Tale, and dwelt with rapture upon the remorse of Phoebus for having slain his adulterous wife. . . .

[T]he Tale is well done, with a proper sense of what we once heard Mr. Wordsworth call the great poet’s dramatic skill and courage, in making the Manciple, whose only object in life was to be a trusty domestic, draw this moral alone from the Tale, passing by all the crime, rashness & misery of the tragedy, as if they were things that would happen in the best-regulated families, and that servants should see all and say nothing.What Field seems not to have known, or perhaps to have suppressed, is that Wordsworth had modernized “The Manciple’s Tale,” and had originally offered it to Thomas Powell for publication in Chaucer Modernized. He withdrew the offer, however, after family and friends complained about the tale’s bawdiness.12↤ 12 Wordsworth initially offered “The Manciple’s Tale” to Powell in a letter dated “[late 1839]” by Alan Hill. Objections were raised by Edward Quillinan and, perhaps, Isabella Fenwick, and in a letter of 1 May 1840, Wordsworth withdrew his offer. See The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, ed. Alan Hill, 7 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1982) 6: 755-56, 7: 35, 39, 71. In any case, it is clear that Field was interested in this project, and in Wordsworth’s questionable alliance with Horne and Powell, well before the volume was published. His review may even have been written as a kind of public reminder to Wordsworth to be more selective in his literary associations.13↤ 13 Field’s suspicions of Powell were later borne out in ways he could not have predicted. Powell was discovered to have supported himself by embezzlement and forgery; he faked insanity to avoid prison, and spent the rest of his days in New York. See Blainey 114.

Two problems remain. First, why was the review never published? Second, why was Field so interested in promoting Blake’s reputation that he would drag him by the heels into a review like this? And about both problems we can only speculate. Chaucer Modernized appeared in time for the Christmas trade in 1840 and was reviewed in three periodicals: Monthly Magazine, on 5 January, The Athaenum, on 6 February, and Church of England Quarterly Review in April.14↤ 14 These reviews are all listed in N. S. Bauer, William Wordsworth: A Reference Guide to British Criticism, 1793-1899 (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1978) 133-35. The first and third of these reviews were favorable, although J. A. Grimes in Monthly Magazine points out several errors in Horne’s translation of the “General Prologue.” But Henry Chorley in the Athaenum, although kind to Wordsworth and Hunt, called Horne’s efforts a “counterfeit presentment,” called attention to several of the same faulty passages that Field did, and complained that “Father Chaucer [has been] reduced to sickly weakness and effeminacy.”15↤ 15 The Athaenum (6 February 1841): 107-08. Blainey 105, 115, notes that Chorley was a perennial enemy of Horne. Field himself was not in England at this time: he was in Gibraltar until autumn, then returned to England to take up permanent residence for the first time in over a decade.16↤ 16 Little 51. He may have written the review abroad, but probably wrote it after his return, and it is likely that publishers considered it somewhat repetitive and rather old news. Deprived of a public forum, Field may then have given the review to Wordsworth, as both a token of appreciation and as a quiet reminder about associating[e] himself with dubious literary enterprises.17↤ 17 Field had the opportunity to give Wordsworth the review (providing he had finished it by then) in September 1841 when he spent time in the Lake District (Little 51). Field also tells of helping Wordsworth write an article on Talfourd’s copyright bill at this time. But since the manuscript, which is still in its original blue cover, lacks a presentation autograph, it seems unlikely that Wordsworth ever saw it. Probably the review found its way into the Dove Cottage Papers sometime after Field’s death in 1846.18↤ 18 Shortly after Wordsworth’s death, as materials for Christopher Wordsworth, Jr.’s memoir of the poet were being collected, there was correspondence between Robinson and Edward Quillinan about Barron Field’s papers. It seems possible that Robinson or Edward Quillinan may have had access to them, so perhaps at that time the review passed into the hands of the Wordsworth family. See The Correspondence of Henry Crabb Robinson with the Wordsworth Circle, ed. Edith Morley, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1927) 2: 738-39.

Why Field should go so far out of his way to call our attention to Blake is an even more intriguing question. Field did not attend the 1809 Blake exhibition—he apparently had never heard of Blake before 1813—so unlike Crabb Robinson he would not have seen the original painting of the Canterbury Pilgrims, nor any of the other impressive artworks on display.19↤ 19 According to Bentley, Blake Records 231, “Crabb Robinson wrote in his Diary for Tuesday, January 12th, 1813: ‘In the Eveng at Coleridge’s lecture. And then at home. Mrs. Kenny[,] Barnes & Barron Field there—The usual gossiping chat—F & B. both interested by Blake’s poems of whom they knew nothing before[.]—’” Nor did Field, to our knowledge, ever meet Blake; his only direct contact seems to have been with Catherine Blake in 1828. Yet the print and catalogue he owned, his reading of Cunningham’s biography, and his conversations about Blake with Robinson and Lamb impressed him begin page 94 | ↑ back to top deeply. Field’s review thus serves to underscore how often Blake was a subject of discussion among members of the Wordsworth circle, and how much we owe to figures like Charles Lamb and Henry Crabb Robinson for helping to preserve the reputation of William Blake.