article

begin page 104 | ↑ back to top“Sun-Clad Chastity” and Blake’s “Maiden Queens”: Comus, Thel, and “The Angel”

. . . To him that dares

Arm his profane tongue with contemptuous words

Against the sun-clad power of chastity;

Fain would I something say, yet to what end?

(Milton, A Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle, 1634 [Comus] 779-82)

In her discussion of Blake’s illustrations to Milton’s Comus, Pamela Dunbar comments:

Blake was a tireless critic of the “double standard” of sexual morality and of the repression of “natural desire.” It is therefore not surprising that he should have transformed Milton’s “sage/ And serious doctrine of virginity” (785-86) into a sterile and destructive dogma, and his virtuous Lady into a coy, deluded and self-denying miss. . . .(10)

The work in which this “sage / And serious doctrine” was mounted was the subject of the earliest of Blake’s commissioned series of Milton illustrations. Blake executed them for the Reverend Joseph Thomas in c. 1801;1↤ 1 Butlin 1: 373-74. The “Thomas” set of Comus illustrations is now in the collection of the Huntington Library in San Marino, CA. Blake executed a second set for Thomas Butts c. 1815; this series is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA. but he had long reflected on the theme of Milton’s masque, with wit and subtlety arming his “profane [read: ‘iconoclastic’] tongue with contemptuous words” against it in the poems I discuss in this essay (to mention only two), years before he made Comus the subject of a series of paintings.

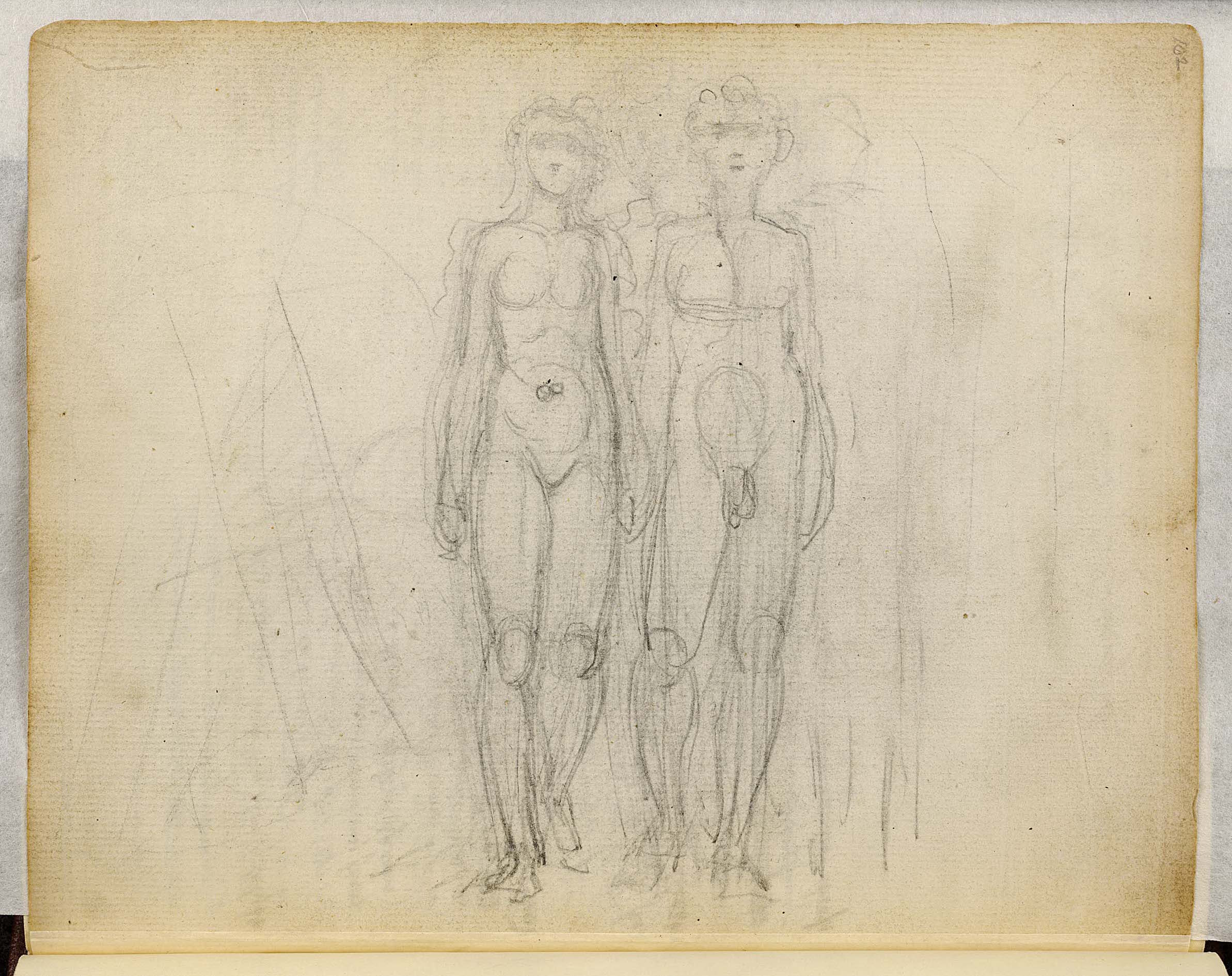

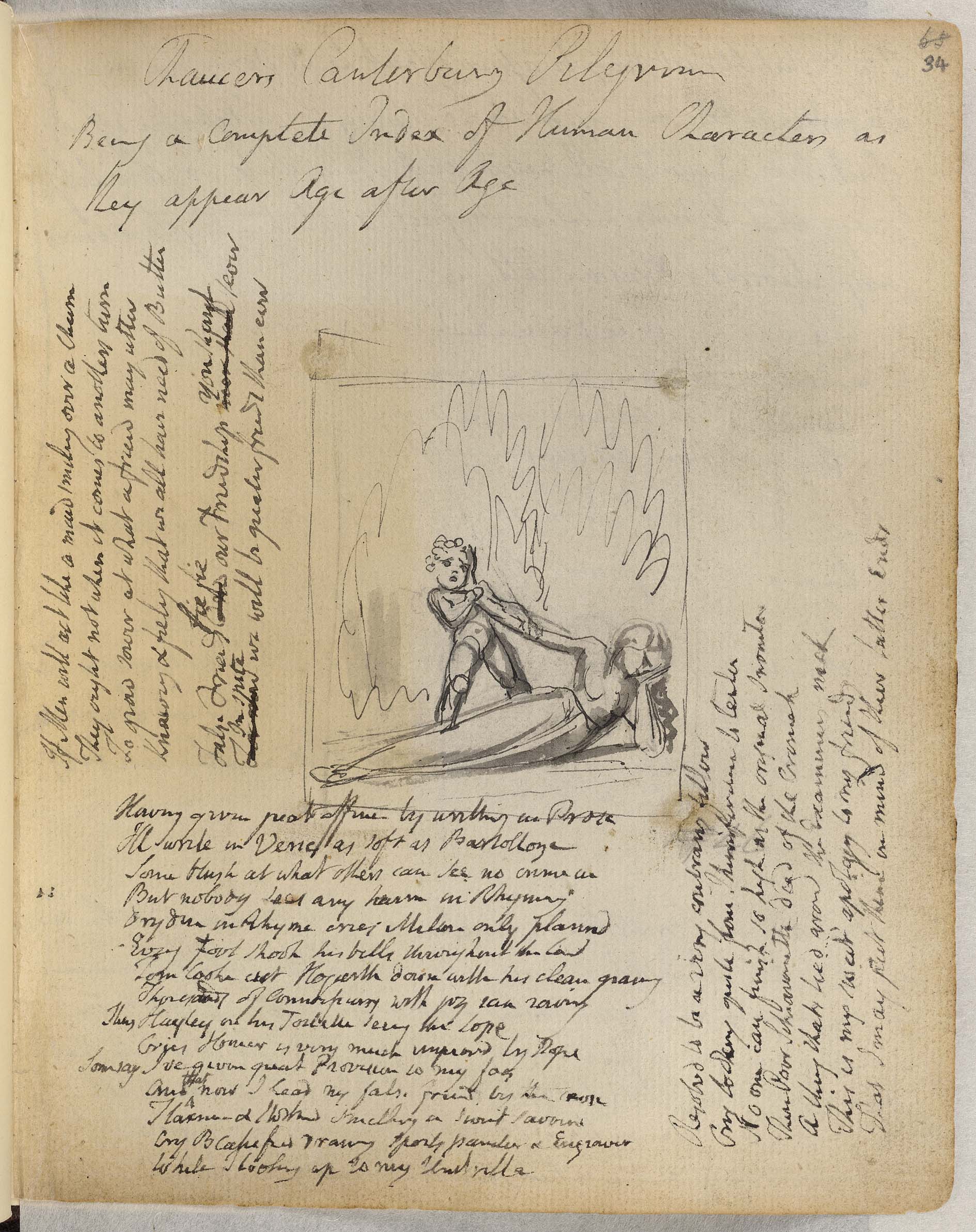

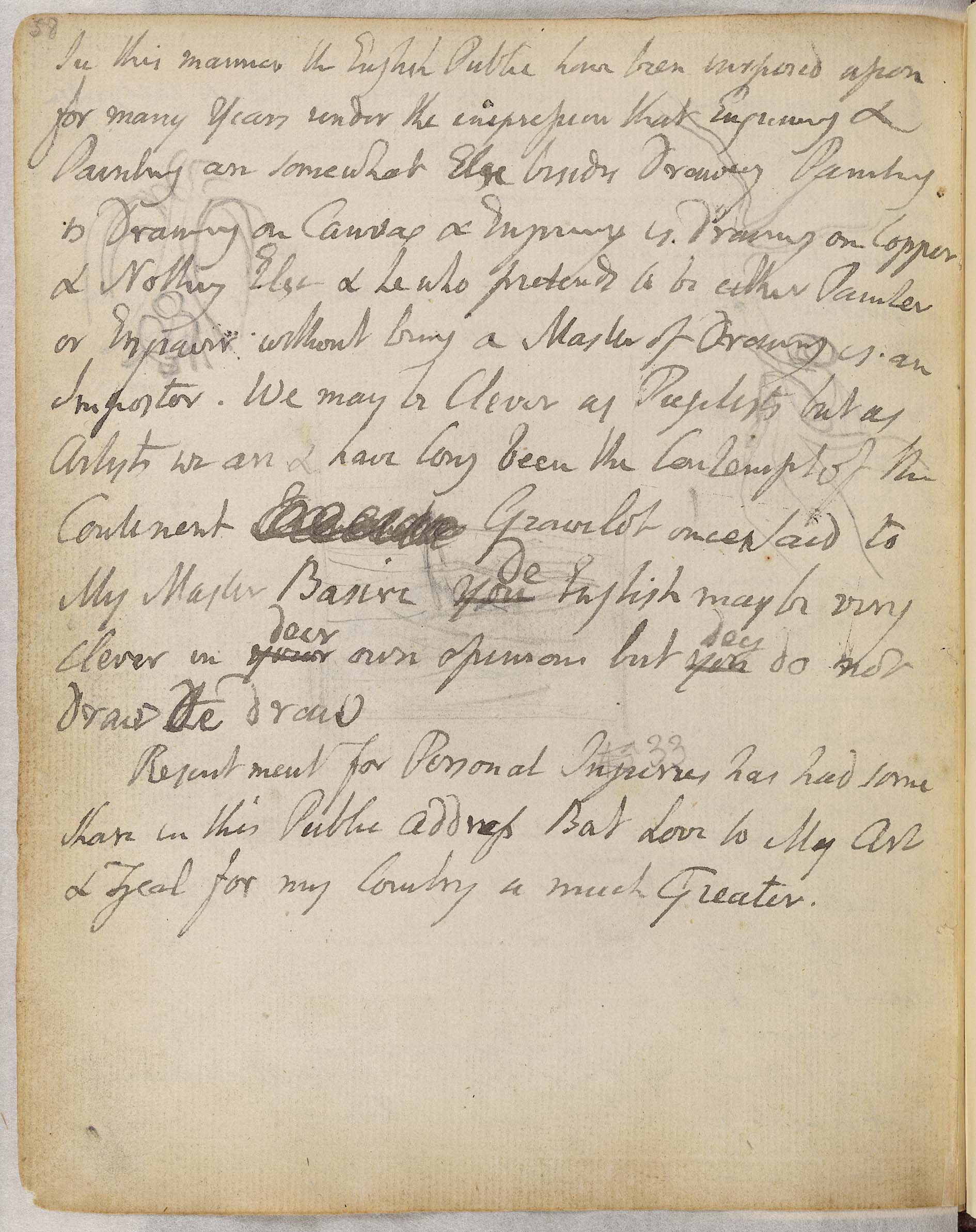

Comus was demonstrably one of the works on Blake’s mind while he was sketching motifs for The Gates of Paradise in his Notebook during 1790-93, for he jotted down quotations from it on pages 30 and 36 of the Notebook.2↤ 2 Butlin 1: 90-91. Characteristically, it was Milton’s virtuous Lady who came contrarily into his mind when, while copying and drafting poems into the Notebook at some time during this period,3↤ 3 Erdman suggests “a beginning date of 1791 or later, for the inscribing of the Songs” and a terminal date of late October 1792. (The Notebook of William Blake, page 7 of the editorial preface). Blake opened it at page 102, and paused to. contemplate a sketch of his own (illus. 1) which had been suggested by a passage from Book 4 of Paradise Lost:

. . . into their inmost bowerThe pencil sketch shows two nude figures, seen full-frontal, walking hand in hand toward, and looking directly at, the viewer: a long-haired Eve, and a curly-haired Adam, much as they appear in Blake’s earliest extant Milton illustrations.4↤ 4 The sketch on page 102 of the Notebook was not used by Blake in this form in any other extant composition. It is part of a series of illustrations of Paradise Lost interspersed among designs for the emblem book The Gates of Paradise. Blake’s so-called “Milton Gallery” is dated by F. W. Bateson (105) c. 1790-91. See Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire (437-39). (Butlin 1: 104; compare with the earliest representation of Adam and Eve, 2: pl. 111, 1: 40). The drawing in the Notebook is reproduced as no. 14 in Keynes (1970).

Handed they went; and eased the putting off

These troublesome disguises which we wear,

Straight side by side were laid, nor turned I ween

Adam from his fair spouse, nor Eve the rites

Mysterious of connubial love refused. . . .

(PL 4.738-43)

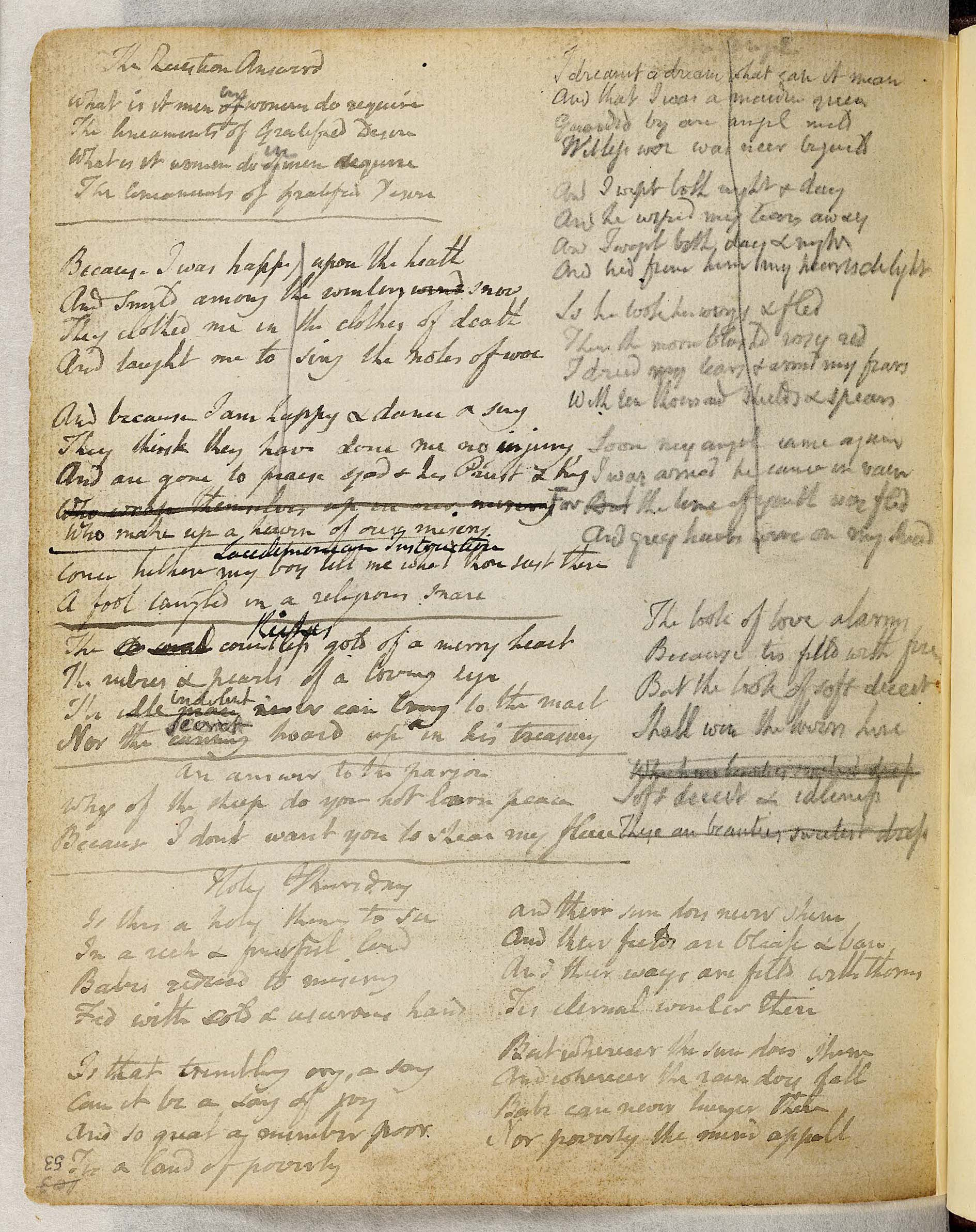

Blake covered the page facing this drawing (Notebook 103) with drafts of poems (illus. 2). Three poems that appear here were to be etched as Songs of Experience: “The Chimney Sweeper,” “Holy Thursday,” and “The Angel.” begin page 105 | ↑ back to top The first two of these arise from “Songs of Innocence” having the same titles. The third, “The Angel,” was inspired in part by the design that presented itself to his eye on the opposite page of the Notebook. Blake obviously recalled the context in Paradise Lost of the lines he had illustrated, and affirmed for himself Milton’s indignant condemnation there of “hypocrites” who “austerely talk / Of purity . . . and innocence, / Defaming as impure what God declares / Pure . . .” (PL 4.744-47). However, in the spirit of his own dictum

I dreamt a dream what can it meanThe speaker of “The Angel,” in her dream-life a “maiden queen,” rebuffs her angel-lover because of her own fears and inhibitions, keeping him in a state of tantalized frustration both in her subconscious and her waking life. Soon it is too late to recant: ↤ 6 The last two lines of “The Angel” were taken up by Blake from the ending he had devised to the long first draft of “Infant Sorrow,” already written into the Notebook some pages earlier (E 794, 797-99). They there conclude a poem, intended to encompass human life from birth to old age, which also emphasizes the self-defeating consequences of society’s hypocritically repressive attitudes towards sexuality.

And that I was a maiden queen

Guarded by an angel mild

Witless woe was ne’er beguiled

And I wept both night & day

And he wiped my tears away

And I wept both day & night

And hid from him my hearts delight

So he took his wings & fled

Then the morn blushd rosy red

I dried my tears & armd my fears

With ten thousand shields and spears

Soon my angel came again

I was armd he came in vain

[But del.] For the time of youth was fled

And grey hairs were on my head

(Notebook 103. The version engraved for the Songs of Experience differs only in punctuation.)

I was arm’d, he came in vain,This petrified virgin inhabits a fallen and time-bound world in which her imagination, corrupted by the “defamation” of sexuality perpetrated by those Milton calls “hypocrites,” creates a “horrible darkness . . . impressed with reflections of desire.”7↤ 7 Visions of the Daughters of Albion 7.11, E 50. Sketches for the designs finally etched with the text of this work appear in various parts of Blake’s Notebook, suggesting that this illuminated book (dated 1793 on its title page) was in the making during the same period as the Songs of Experience. (See page 49 of Erdman’s preface to the facsimile.) An engraving of 1790 attributed to Blake (illus. 3) shows a nude woman, revealingly draped, asleep in a sitting position on a couch. A winged Cupid aims an arrow at her mons veneris, while from beneath the couch emerges a small, terrifyingly monstrous creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull elephant, complete with sharp upcurved tusks and phallic proboscis. (Blake placed a similarly elephant-headed figure, less sinister but obviously having the same symbolic intention, among the monsters at the banqueting table in his second version of the banquet of Comus [illus. 4].8↤ 8 This engraving, executed after Fuseli’s design entitled Falsa ad Coelum mittunt Insomnia Manes, is reproduced as pl. XXXV in Keynes [1956]; and in Bindman as pl. 80. The banquet scene in the later Comus series is reproduced by Butlin in 2: pl. 628. (My reading of the significance of the elephant-headed figure in the Comus series does not preclude Pamela Dunbar’s suggestion [24] that it represents the vice of Gluttony.) ) The engraving casts an interesting light on Blake’s speculations begin page 106 | ↑ back to top

For the time of youth was fled,

And grey hairs were on my head.

(14-16, E 24)6

The “maiden queen” of “The Angel” is evidently derived from the classical virgin goddess

of the moon, Diana. Blake may have been influenced by Milton’s description of the

nocturnal scence as Adam and Eve enter their nuptial bower, when the moon “rising in

clouded majesty, at length / Apparent queen unveiled her peerless light”

(PL 4.607-08). But his image owes more to “Dian the huntress . . . fair

silver-shafted Queen forever chaste” (440-41) from Milton’s Comus.10↤ 10 Bette Charlotte Werner explains the presence of

a mysterious female driving a team of serpents in the sky in Blake’s fourth

Comus illustration (in both series, the Attendant Spirit addressing the

Brothers) by identifying her with the moon-goddess Diana, “represented as a severe and

uncompromising guardian of chastity” (31). The angel of Blake’s poem also emerges, in an

ironically modified form, from passages of Comus,11↤ 11

Compare as well the Lady’s soliloquy:

O welcome pure-eyed Faith, white-handed

Hope,

Thou hovering angel girt with golden wings,

And thou unblemished form

of Chastity . . .

. . . [I] now believe

That he, the Supreme Good . . .

Would send a glistering guardian if need were

To keep my life and honour

unassailed.

Comus 212-18

See my discussion below of the Cloud in

The Book of Thel. together with the maiden’s dream:

So dear to heaven is saintly chastity,

That when a soul is found sincerely so,

A thousand liveried angels lackey her,

Driving far off each thing of sin and guilt,

And in clear dream and solemn vision

Tell her of things that no gross ear can hear. . . . (452-57)

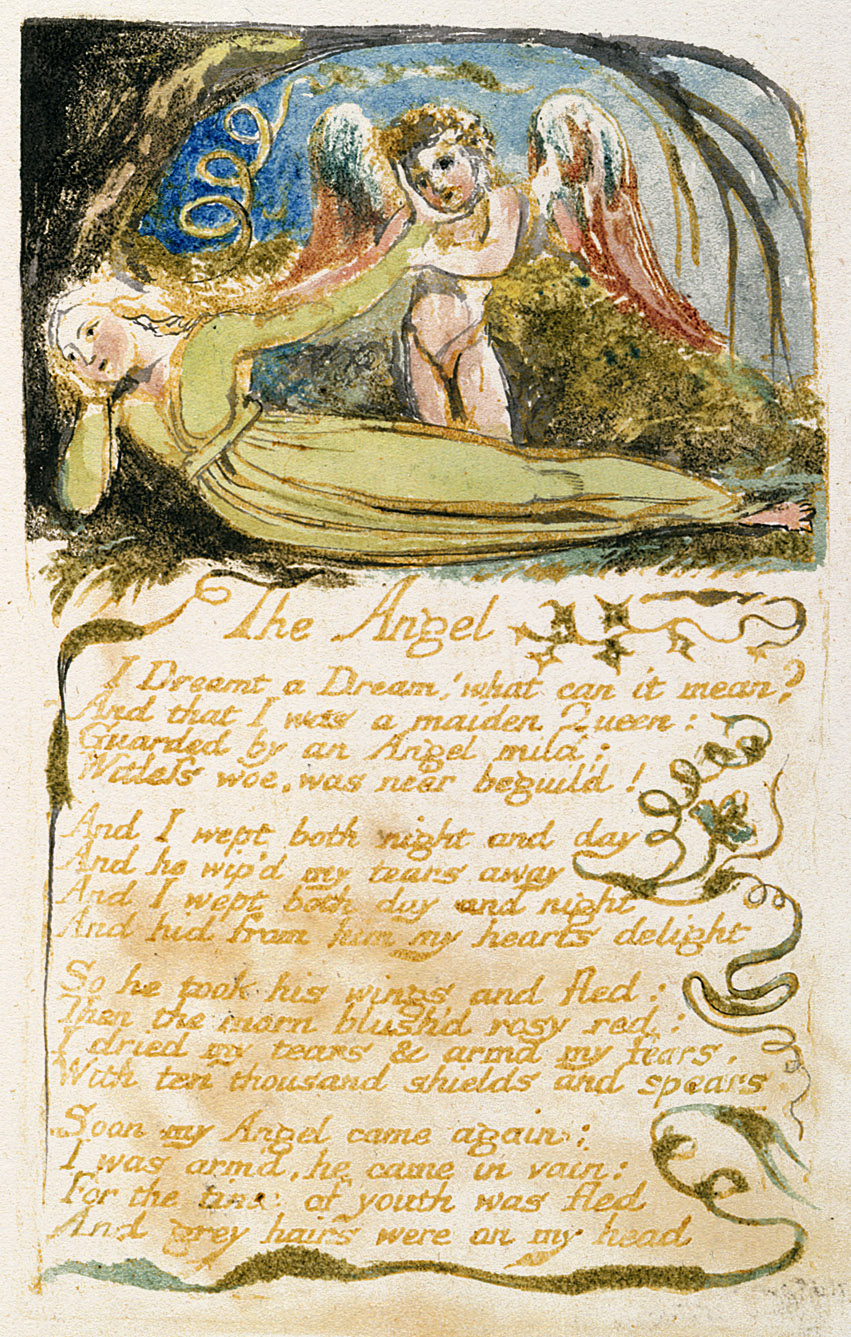

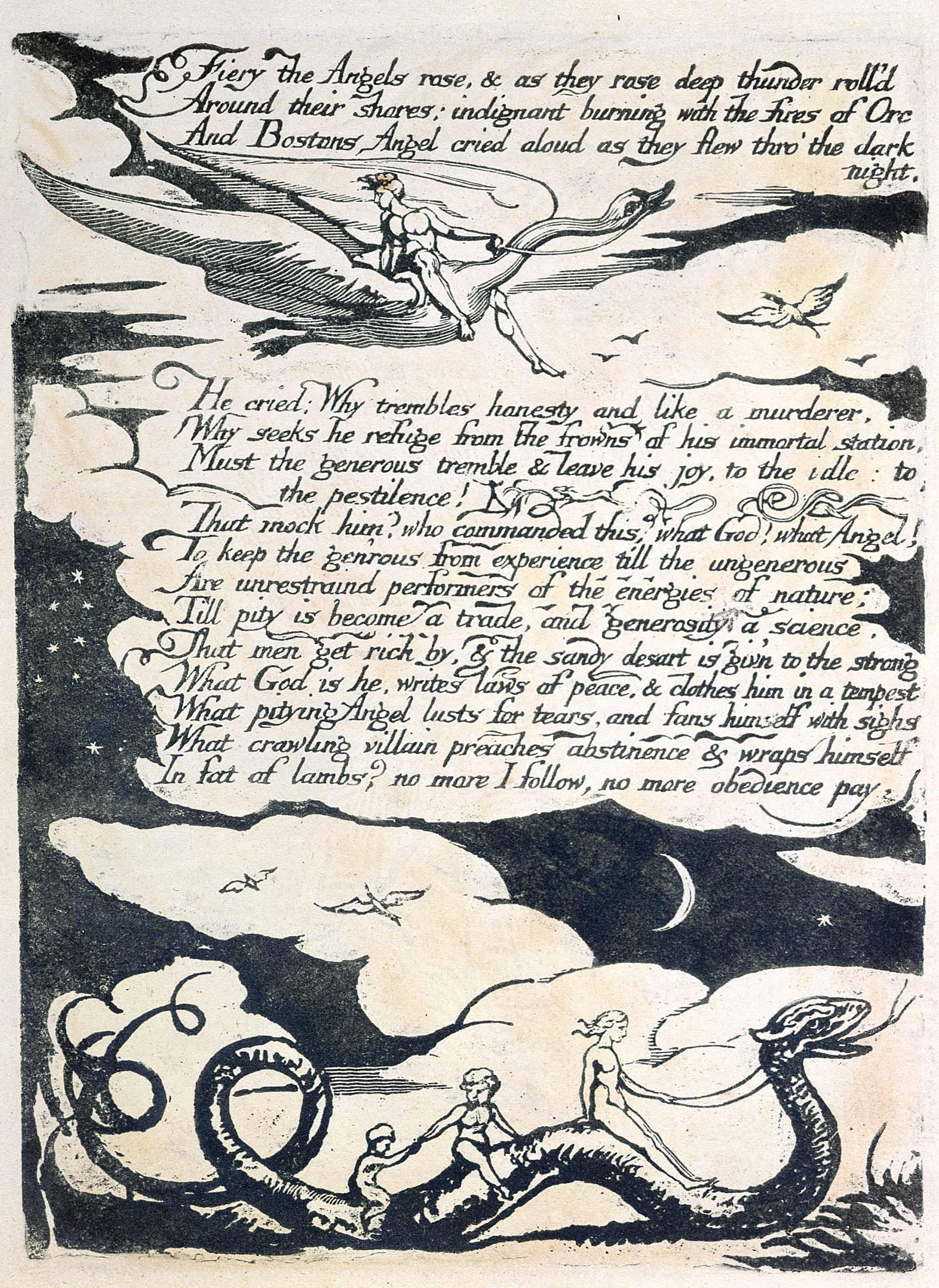

The plate of “The Angel” in the Songs of Experience12↤ 12 Blake first sketched this design as one of his “Emblem” series, numbering it 42, on page 65 of the Notebook (illus. 7). In the original the “angel” has no wings and is obviously an importunate infant, possibly the same who is being lifted up by the hair from what looks like a cabbage-patch in the emblem-design on an earlier page of the Notebook (illus. 6). The latter eventually became pl. 1 of the 1793 series For Children: The Gates of Paradise, entitled “I found him beneath a Tree” (E 32). Blake evidently perceived a different application for “Emblem 42,” although the themes of the two Notebook designs are related. “I found him beneath a Tree” refers to the prudish fiction that mothers found their babies in cabbage-patches, an answer supplied to children in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when they asked where babies came from. The “witless woe,” frigidity and fear of the “maiden queen” of “The Angel” seem a likely development from an upbringing of this kind. shows the recumbent maiden, clothed in a long gown, leaning her face on one hand while with the other, in an absurd gesture of repulsion, she pushes away the angel, who seems to be trying to impart to her “things that no gross ear can hear” (illus. 5-7). Her expression betrays “witless woe” and preoccupation with her inner conflict; his reflects distress at the rejection, while his arms reach out to her, attempting vainly to persuade her to “turn away no more.”13↤ 13 “Introduction.” Songs of Experience l.16, E 18. (The plate of “The Angel” is reproduced in Erdman, Illuminated Blake 83.) In the line “Then the morn blush’d rosy red. . . ”[e] Blake recollects Adam’s description of the maiden modesty of Eve on the first night of their marriage: “[e] . . . To the nuptial bower / I led her blushing like the morn . . .” (PL 8. 510-11). But, Blake implies, in the fallen world, Eve’s “sweet reluctant amorous delay” (PL[e] 4.311) is perverted to a “hypocrite modesty,” such that “When thou awakest . . . Then com’st thou forth a modest virgin, knowing to dissemble. . . .”14↤ 14 Visions of the Daughters of Albion 6.8-10, 16, E 49. The hysterical defence of her chastity with “ten thousand shields and spears” by the protagonist of “The Angel” is a parody of the simile in Milton’s Comus, in which the chaste virgin is compared to “a quivered nymph with arrows keen,” whose “virgin purity” encases her in “complete steel,” proof against “savage fierce, bandit, or mountaineer”

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Little did I dream that I should have lived to see disasters fallen upon her in a nation of gallant men. . . I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. (76)15

The charming Book of Thel, Blake’s earliest prophetic book, probably composed some time before “The Angel,”16↤ 16 Blake began to etch The Book of Thel, the earliest of his “prophetic books,” in 1789 (according to the title page). Erdman notes that pl. 6, carrying the final section of the poem, and the plate bearing “Thel’s Motto,” “are later than other plates of Thel in style of lettering . . . Hence [plate 6] may be a revised version of the poem’s conclusion” (Illuminated Blake 40). Kathleen Raine (72-75) believes that there are “unmistakeable allusions” in The Book of Thel to Porphyry’s Neoplatonic symbolism in his treatise on Homer’s Cave of the Nymphs, which Blake may have derived from Thomas Taylor’s translation published in 1788; and also that Blake drew in the final section of the poem on Taylor’s A Dissertation on the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries, published in 1790. is also both inspired by Milton’s Comus and opposed in principle to it.17↤ 17 S. Foster Damon was the first modern critic to recognize the link between Comus and The Book of Thel, in his 1957 article “Blake and Milton.” Rodger L. Tarr perceives Thel as a kind of “negation” of Milton’s doctrine concerning the wisdom of virginity. The virgin Thel, whose name means “wish” or “will” (from the Greek verb meaning “to desire”), is the only one of Blake’s personages who is given the option of accepting or rejecting the fallen condition of mortality. Thel avails herself of this privilege, choosing, when she has previewed this “land begin page 107 | ↑ back to top of sorrows & of tears” (Thel 6.5, E 6), to flee “back . . . into the vales of Har” (6.22, E 6).18↤ 18 “The vales of Har” (from Blake’s earlier poem Tiriel 2.4, E 277) offer scenes of pastoral serenity. Though apparently associated with primal innocence, they prove ultimately to be a setting for the condition of senility, or a form of arrested emotional development. However, see note 52 for a different critical view. The poem makes it clear that the “daughter of beauty” will indeed, as she foresees, “fade away” (Thel 1.3, 3.21 and 5.12, E 3, 5, and 6). As Spenser put it in a passage that Blake certainly had in mind, “. . . that faire flowre of beauty fades away, / As doth the lilly fresh before the sunny ray.”19↤ 19 The Faerie Queene 3.4.38.8-9. See the discussion below of the significance of the “sunny” flocks tended by Thel’s sisters. Although my own reading of the poem takes a somewhat different line from hers, I do agree with Kathleen Raine’s emphasis (1: 106) on this and other parallels between Blake’s poem and Spenser’s “Garden of Adonis,” and with her assertion that “Mutability is Thel’s theme, as it was Spenser’s” (1: 100). Further Spenserian sources for The Book of Thel, employed by Blake in a “contrary” spirit, are explored by Robert F. Gleckner (31-45 and 287-302). Gleckner demonstrates[e] persuasively that in Thel Blake parodies Spenserian and Petrarchan “sublimations of the senses and desire” (32), both in the Amoretti and in the figure of Alma in Book 2 of The Faerie Queene. Gleckner also relates Thel’s wish “to die because she is of no ‘use’” (293) especially to the encounter between Spenser’s Redcrosse Knight and Despaire in Book 1, showing that “Thel is a severe attack upon the underpinnings of Spenser’s Book I and the language in which it is couched” (288). She will leave behind no trace or useful legacy of her existence—“And all shall say, ‘Without a use this shining woman liv’d . . .’” (Thel 3.22, E 5)—because she refuses to commit herself to earthly generation, fearing the pains of Experience that inevitably accompany sexuality in the fallen world. The Book of Thel affirms that sexuality, and the giving of oneself in love to procreation, is good, and a necessary commitment to life on earth. For the most part it does so within a gentle, almost childlike ambience that sets this poem apart from the intensity of the Songs of Experience and the later prophecies,20↤ 20 S. Foster Damon (1965), noting that Thel does not reappear in any other of Blake’s writings, commented disarmingly that she is “far too nice a girl to fit in amongst Blake’s furious elementals” (401). Damon speculated that Blake’s account of Thel may have been an allegorized narrative woven about a miscarriage, or the premature birth and death of an infant, perhaps Blake’s own child. and places it between “Innocence” and “Experience,” into which latter condition

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The Book of Thel shares its pastoral setting with both Comus and the Songs of Innocence.22↤ 22 Concerning Blake’s “idea of pastoral,” Wagenknecht writes that “in terms of the Songs [of Innocence and Experience] the idea of the pastoral had emerged as the vehicle for conveying Blake’s ambiguous and agonized approach to the problem of ‘Generation’” (5). This view is congenial to my own approach to The Book of Thel, about which Wagenknecht adds that its nature is best appreciated “via the pastoral ironies and ambiguities of the Songs” (148). “The secret air” Thel seeks out “down by the river of Adona” (1.2, 4, E 3) was inspired by the “regions mild of calm and serene air” (Comus 4) from which the Attendant Spirit descends, the “broad fields of the sky” (978) to which he returns again in the closing lines of Comus. Here Adonis appears:23↤ 23 Wagenknecht describes the story of Venus and Adonis as “a primary myth for pastoralists” (2). Raine points out an allusion to Adonis concealed in the title page emblem of The Book of Thel: The flowers, from whose centers spring little lovers in amorous pursuit and flight, are pasqueflowers, anemone pulsatilla . . . The anemone is the flower of Adonis, into which he was, according to tradition, metamorphosed. . . . (1: 105) She describes these flowers on the title page as an allusion to the theme of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, adding that “the association of the flower with Easter (pasque) is itself significant” (1: 105).

Iris there with humid bow,Milton’s rainbow “drenches” and nourishes “beds of hyacinth and roses,” symbolic of regeneration and love, where the youth Adonis, beloved of “the Assyrian queen” Venus, lies

Waters the odorous banks that blow

Flowers of more mingled hue

Than her purfled scarf can shew,

And drenches with Elysian dew . . .

Beds of hyacinth and roses,

Where young Adonis oft reposes,

Waxing well of his deep wound

In slumber soft, and on the ground

Sadly sits the Assyrian queen. . . .

(Comus 991-1001)

All be he subiect to mortalitieThel, lamenting by the river of Adona, compares herself to a “watry bow” (Thel 1.8)—Milton’s “humid bow.” Through a series of parallel similes (“shadows in the water,” “a smile upon an infants begin page 108 | ↑ back to top

Yet is eterne in mutabilitie

And by succession made perpetuall. . . .

(47.4-6)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

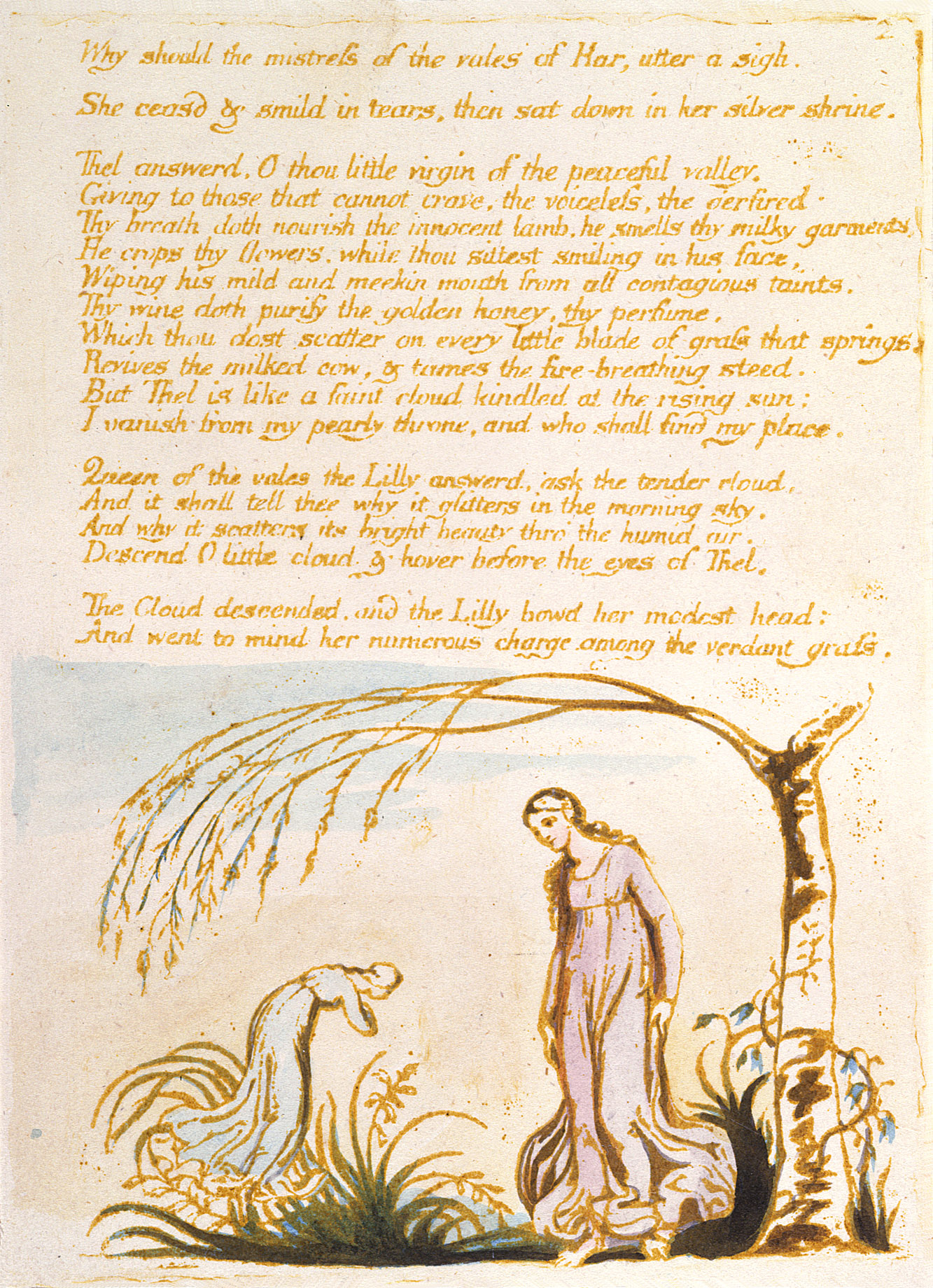

Thel encounters four symbolic figures. The first, the “Lilly of the valley,” is a “gentle maid of silent valleys and of modest brooks” (1.16, 22) who retires after speaking with Thel to a “silver shrine” (2.2) (illus. 8). Blake’s “Lilly” is primarily Spenser’s “faire flowre of beauty [that] fades away,” but this appealing little “watry weed” is also related—through the “twisted braids of lilies” knitted into the “loose train of [her] amber-dropping hair” (861-62)—to Milton’s Sabrina, “a gentle nymph . . . that with moist curb sways the smooth Severn stream” (Comus 823-24). Sabrina, sitting “under the glassy cool translucent wave” (860), is “Goddess of the silver lake” (864) and a patron of maidenhood. She is invoked by the Attendant Spirit to free the Lady held fast by Comus’s magic spell. Blake’s “Lilly,” a self-effacing “little virgin of the peaceful valley” (Thel 2.3), contrasts with the regal Sabrina, whose narcissistic adorning of herself suggests an immature self-involvement rather like Thel’s own.26↤ 26 Irene Tayler notes Blake’s emphasis on the theme of “narcissism[e]” in his first series of Comus illustrations. See especially 71-78 of her essay. Bette Charlotte Werner differentiates between Milton’s perception of Sabrina as an agent of grace, and Blake’s reading of Milton’s imagery in Comus 837-39. Blake, Werner says, perceives that “Sabrina’s restoration, her sea-change, to immortality has been accomplished, not through the paralysis of virginity but through the opening of her senses” (35). The life of the

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

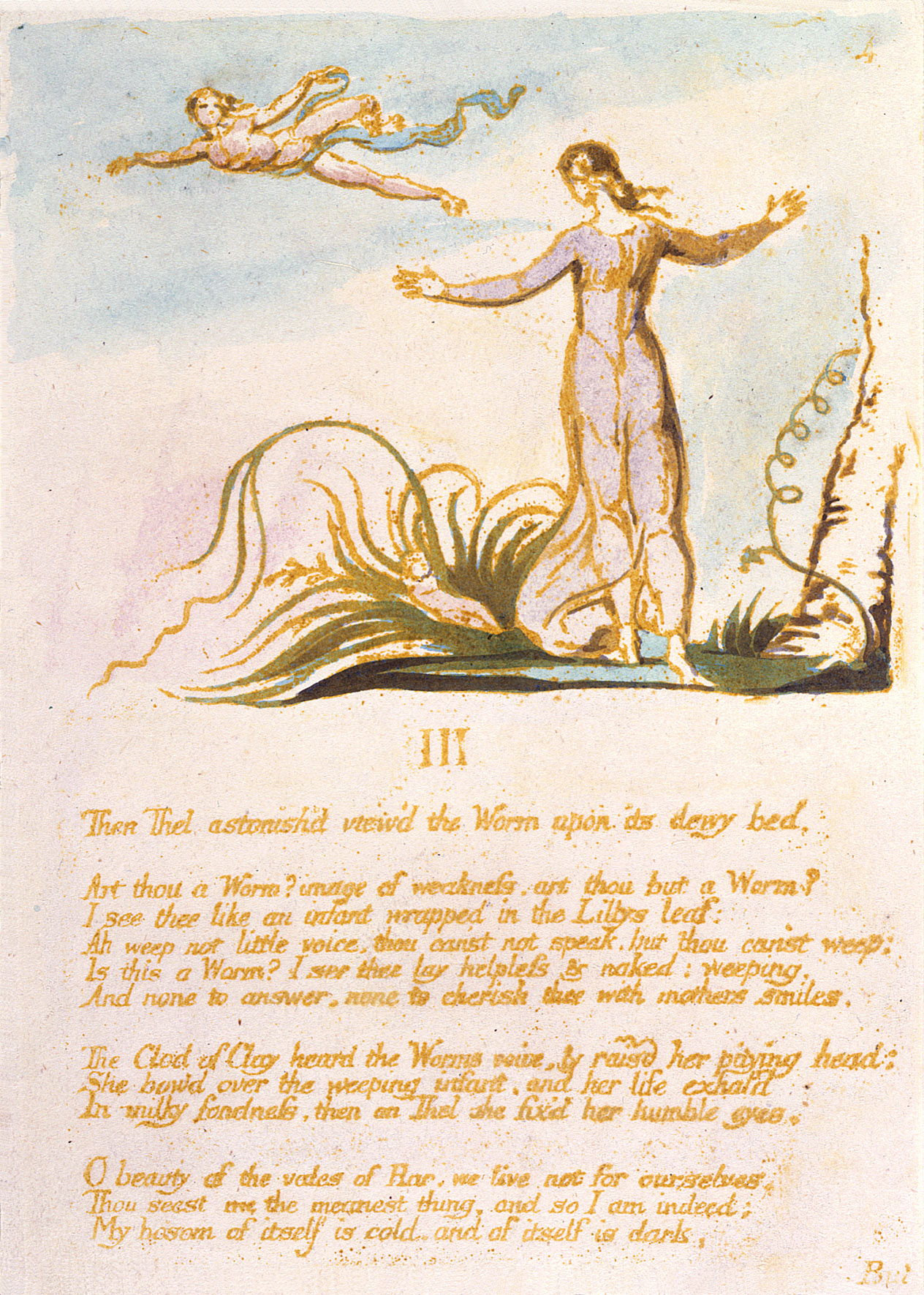

Thel’s second dialogue is with a Cloud (illus. 9) which “shewd his golden head . . . / Hovering and glittering on the air . . .” (Thel 3.5-6, E 4). Blake’s Cloud takes his “bright form” from the “hovering angel girt with golden wings” (Comus 213) who accompanies Faith, Hope, and Chastity in the Lady’s soliloquy in Comus (and is there perhaps to be identified with Hope). He also resembles the “glistering guardian” whom the Lady trusts to keep her “life and honour unassailed” (218-19) (and whose semblance Blake was to borrow for the equivocal guardian of maidenhood in “The Angel”). The Cloud declares to Thel: “O virgin, know’st thou not. our steeds drink of the golden springs / Where Luvah doth renew his horses?” (3.7-8). “Our steeds,” those upon which clouds are mounted in moving about the sky, “renew” their vitality at the same source as the “horses

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

And Phoebus ’gins arise

His steeds to water at those springs

On chalic’d flow’rs that lies . . .

(Raine, 1: 169) Luvah is a symbol of sexuality, wherever he appears in Blake’s later work,28↤ 28 See, for instance, The Four Zoas 7.83.12-16, E 358. and the Cloud is likewise portrayed, both visually and in the text, as a figure of young and virile sexuality.29↤ 29 In Blake’s illumination on pl. 4, the Cloud has the form of a young man, almost naked but with floating drapery flying from his body (Erdman, Illuminated Blake 38). Blake’s figure of Antamon in Europe 14.15-20 (E 65-66) seems to be a development of Thel’s Cloud. Blake may have associated the “golden springs / Where Luvah doth renew his horses” with the “orient liquor” which Comus, descendant of the Sun,30↤ 30 The mother of Comus is Circe, “daughter of the Sun” (Comus 46-57). offers to weary travelers “to quench the drought of Phoebus” (Comus 64-66). That magic potion “flames, and dances in his crystal bounds” (672) as Comus presses it upon the obdurate Lady, urging

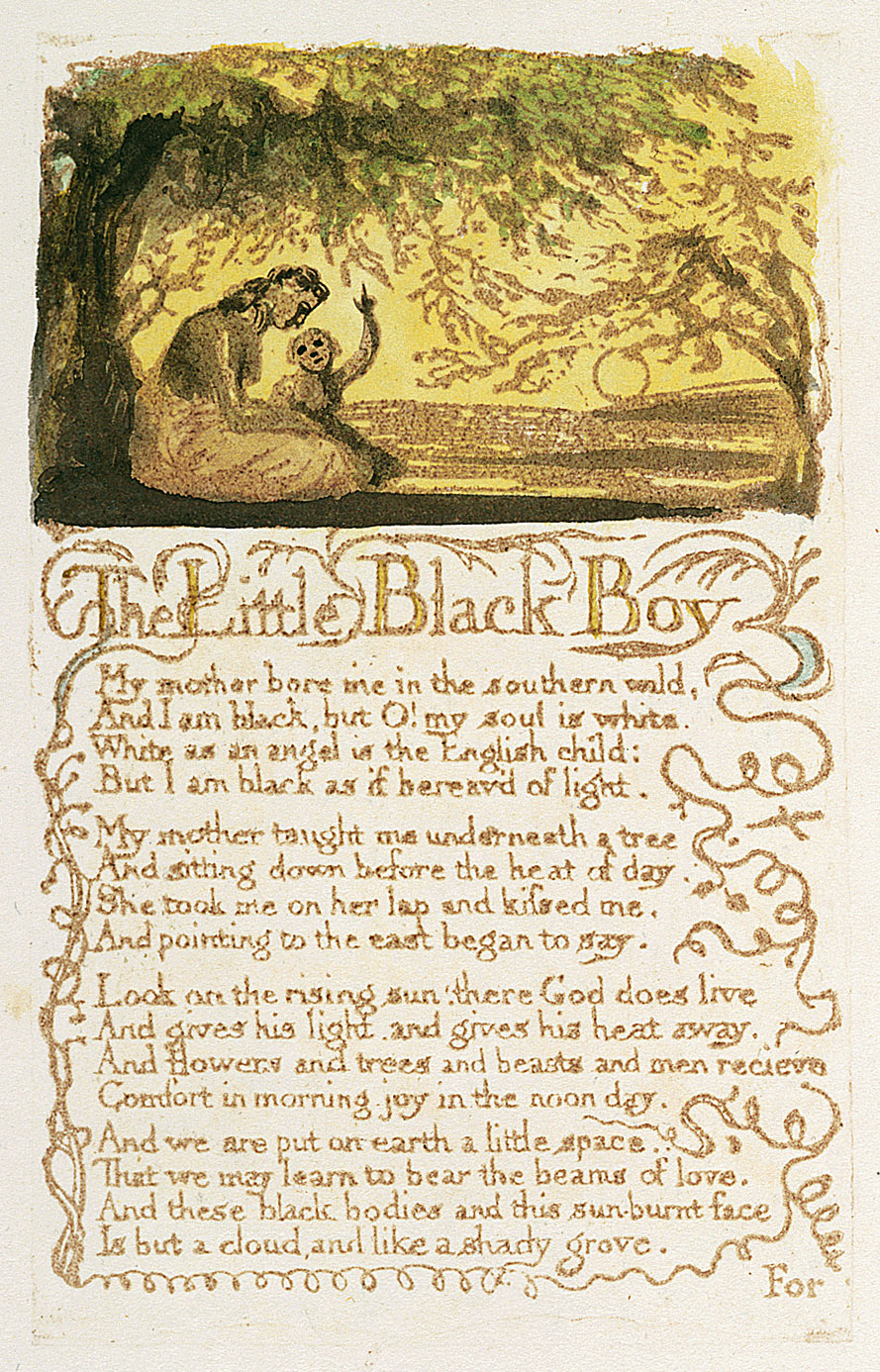

. . . see, here be all the pleasuresThese wonderful images of the fires of lust, spring, morning, and regeneration are tinged in the Miltonic context begin page 109 | ↑ back to top with the evil of Comus’s nature, but Blake was obviously determined that the devil should not have the best tunes or the finest poetry. Blake chose to associate Milton’s phrase from Comus, “the sun-clad power of chastity” (Comus 781), with the lines from Paradise Lost describing the “apostate” Satan “exalted as a god . . . in his sun-bright chariot . . . Idol of majesty divine” (PL 6.99-101). In Blake’s reading of Comus, Chastity is the “apostate,” the “idol of majesty divine,” for the divinity Blake delineates in the Book of Thel is one who blesses earthly plenitude and sustains and encourages its increase: and he is embodied in the sun31↤ 31 Compare the teaching of the Mother in “The Little Black Boy” 9-12: Look on the rising sun: there God does live,

That fancy can beget on youthful thoughts,

When the fresh blood grows lively, and returns

Brisk as the April buds in primrose season. . . .

(667-70)

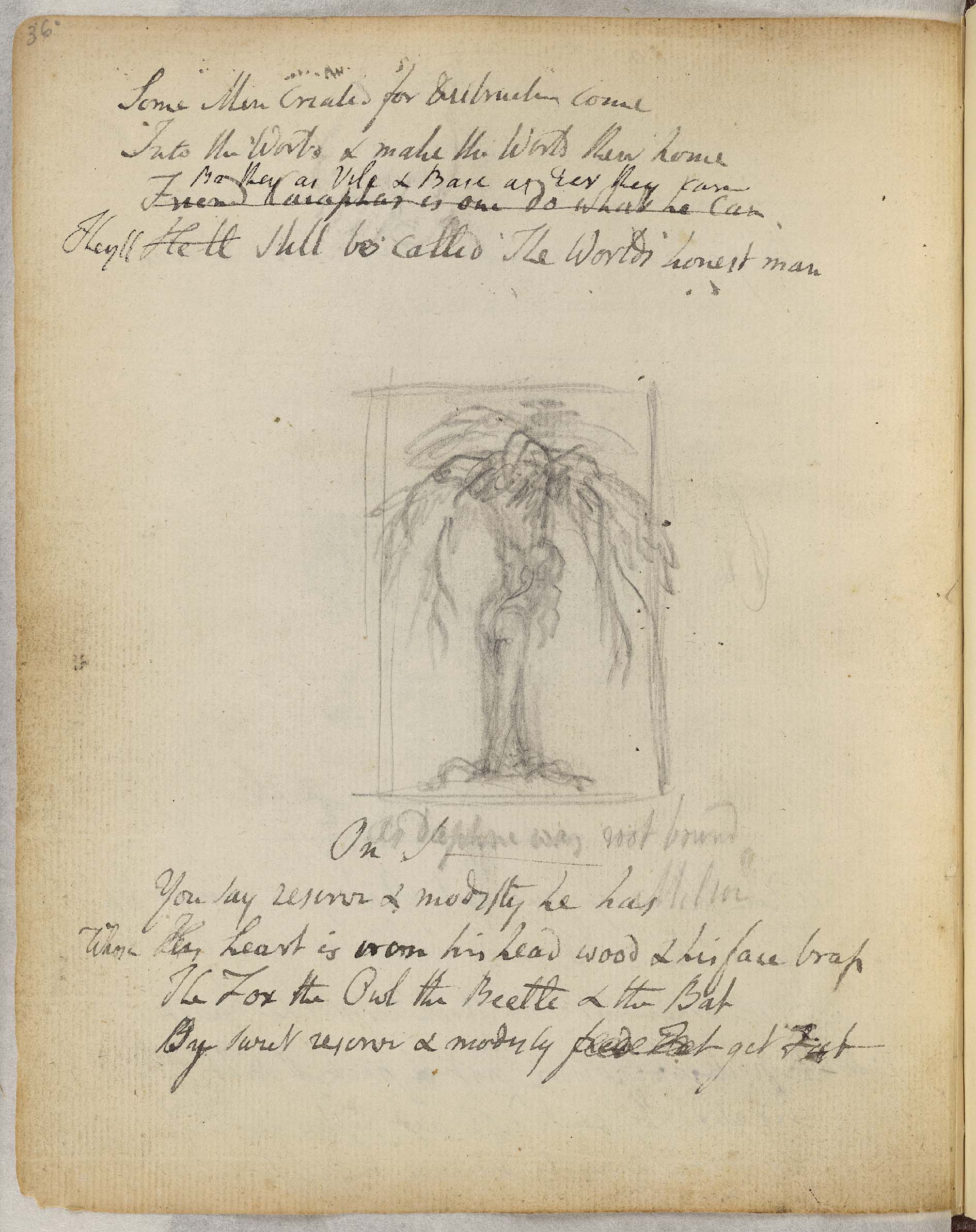

And gives his light and gives his heat away;

And flowers and trees and beasts and men recieve

Comfort in morning, joy in the noonday . . . (Songs of Innocence, E 9) (illus. 10). The Lady in Comus is transfixed by magic to Comus’s enchanted chair, “as Daphne was / Root-bound, that fled Apollo” (660-61). Blake was sufficiently struck by this image to illustrate it in an emblem in his Notebook, inscribing beneath it “As Daphne was root-bound”32↤ 32 Blake inscribed and illustrated these lines on page 36 of the Notebook, and experimented with another version of the same emblem on page 12. His water color illustrations to Comus actually show the Lady “root-bound,” seated in the knotty root of an oak-tree, both at the time when Comus finds her (illus. 12) and after the incursion of her two brothers has set Comus and his train to flight. Butlin reproduces the relevant paintings in 2: pls. 616, 622, 624, 626, and 630. Tayler comments on the Lady’s “rooty chair” on page 53 of her essay. (illus. 11-12). Thel may be seen as an insubstantial analogue of the “Vegetated body” of Daphne,33↤ 33 “This world of Imagination is the world of Eternity; it is the divine bosom into which we shall all go after the death of the Vegetated body” (A Vision of the Last Judgment, c. 1810, E 555). for she too has “fled Apollo.” In the opening lines of the poem she shuns the company of sisters who “led round their sunny flocks” (Thel 1.1, my emphasis).34↤ 34 See note 19 above for this reference to Spenser’s “Garden of Adonis.” Instead she has “sought the secret air, / To fade away like morning beauty from her mortal day . . .” (1.2-3), becoming “like a faint cloud kindled at the rising sun” (2.11). The Cloud, with his “golden head and . . . bright form” is indeed “kindled at the rising sun”—in common with all living beings—but he has followed, not fled, its beams. He rejoices not only in his materialization, “glitter[ing] in the morning sky,” but also in his dissolution, “scatter[ing] [his] bright beauty thro’ the humid air” (2.14-15). In his vaporous state he returns to water his “steeds” at the “golden springs / Where Luvah doth renew his horses” (3.7-8), a generative source where his life is renewed and he comes again into visible being.35↤ 35 Raine’s interpretation of the theme of Thel as “a debate between the Neoplatonic and alchemical philosophies” (1: 99), of Plotinus and Porphyry on the one hand and Paracelsus on the other, dwells especially upon its “watry” imagery, which is “appropriate to the ‘watery’ would of generation of the naiads and their everflowing streams, to the ‘moist’ souls who attract to themselves the hylic envelope” (1: 108) (“. . . the moist envelope of the soul, the generated body, [which is] called a ‘grave’ because in it the soul is dead from eternity, or a ‘bed,’ as the place of the soul’s sleep” [1: 109]).

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Like the “humid bow” of Milton’s Iris, the Cloud is a vital link in the cycle of earthly generation. Comus describes to the Lady his first sight of her two young brothers as ↤ 36 Blake wrote out the first three lines of this passage beneath a sketch of an emblem on page 30 of the Notebook. See Butlin 1: 90 (“Emblem 12”). (The design was used in a slightly modified form on the title page of his Visions of the Daughters of Albion.)

. . . a faery vision,Blake’s Cloud is, like those of Milton in this passage, “plighted”—but with a shift of semantic emphasis.37↤ 37 Milton’s primary sense was “folded,” which gives the current English word “pleated.” He also offers the undercurrent of meaning that relates the rainbow to the “plighting” of God’s covenant with Noah. The Cloud of the Book of Thel is “plighted” in being betrothed to his “partner in the vale” (3.31, E 5), whom he goes to join when he takes leave of Thel. The Cloud’s “partner” is “the fair-eyed dew,”38↤ 38 The “Antamon” of Europe is likewise “prince of the pearly dew” (Europe 14.15, E 65). who “kneels before the risen sun” (3.14), surrendering herself—like Spenser’s “Morning dew” Chrysogone39↤ 39 Chrysogone (in The Faerie Queene 3.6.3ff) was the mother of Belphoebe and Amoret, twin daughters born “of the wombe of Morning dew” (3.6.3.1), miraculously begotten “through influence of th’heauens fruitfull ray” (6.2). Chrysogone is said to have conceived them while sleeping in the sun: The sunne-beames bright vpon her body playd,

Of some gay creatures of the element

That in the colours of the rainbow live

And play i’ the plighted clouds. . . .

(297-300)36

Being through former bathing mollifide,

And pierst into her wombe, where they embayd

With so sweet sence and secret power vnspide,

That in her pregnant flesh they shortly fructifide. (3.6.7.5-9) —to that divine source of life just as obviously as Thel hides away from it when she seeks out “the secret air” (1.2, my emphasis). The “plighted” couple are “link’d in a golden band and never part, / But walk united bearing food to all our tender flowers”(3.12-16, E 5). Like the “Lilly of the valley,” they give selflessly of themselves, both to one another and to others in the fullfilment of social responsibilities. Like her, also, they have an oblique, complex, and significant, relationship with Milton’s argument and imagery in Comus.

The Cloud brings to Thel the Worm, one of the “numerous charge” (2.18) of the “Lilly.” The visual image of the Worm on plate 4 of the Book of Thel40↤ 40 Erdman, Illuminated Blake 38. (illus. 9) confirms that Blake either had in mind, or had already sketched, “What is Man!” the emblem-design he chose to place first in The Gates of Paradise41↤ 41 Erdman, Illuminated Blake 268. (illus. 13). Blake’s introduction of the Worm confirms an association stemming from the caption he wrote in the Notebook beneath his rough sketch of the emblem (illus. 14)—the passage from the Book of Job from which he took its title, ↤ 42 This sketch appears on page 68 of the Notebook; see Butlin 1: 97.

What is Man that thou shouldst magnify him & that thou shouldst set thine heart upon him. (Job 7.17)42Three of Thel’s four visitants—the Cloud, the Worm, and the Clod of Clay—emerge from the context of this verse of Job:

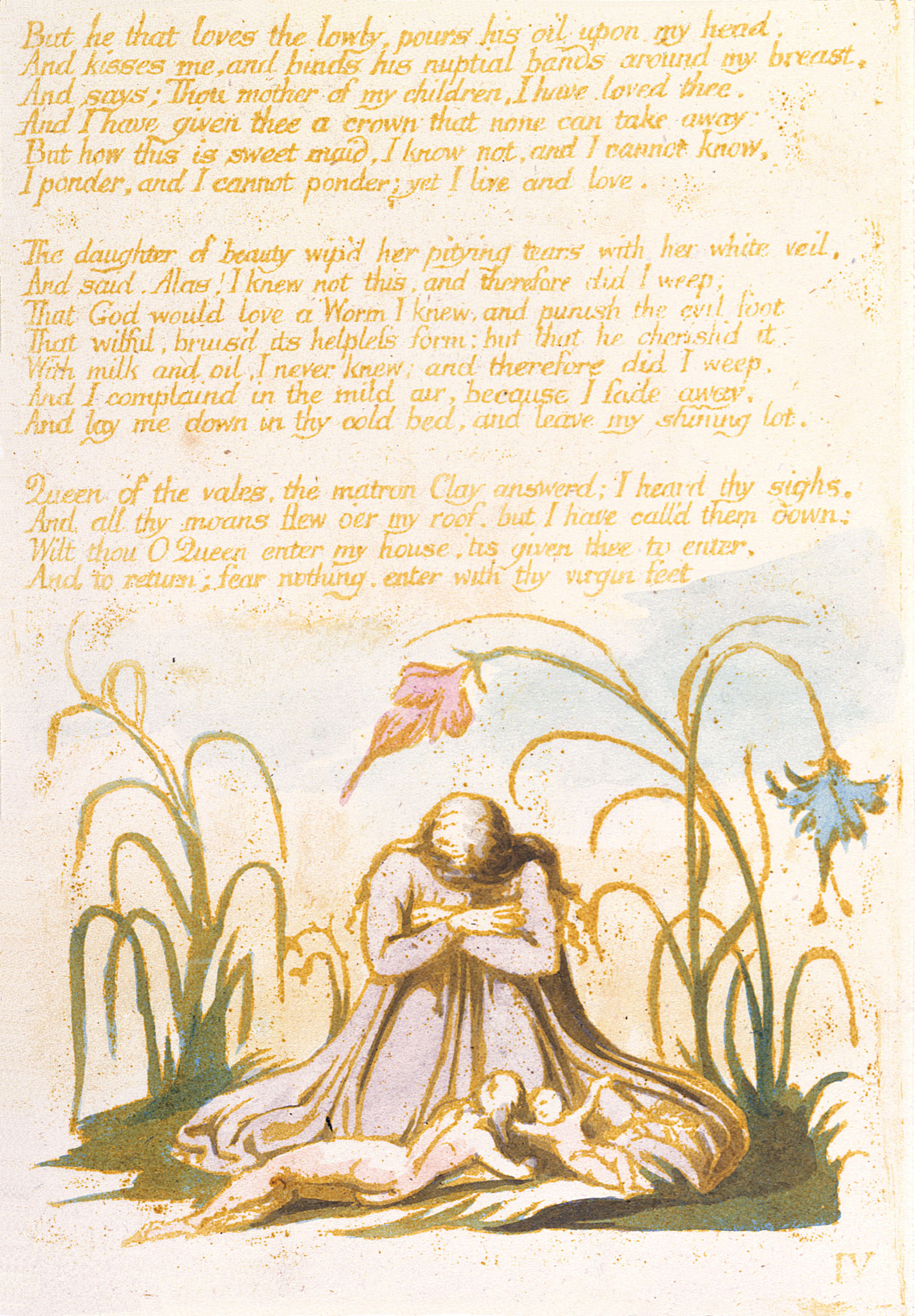

My flesh is clothed with worms and clods of dust. . . . As the cloud is consumed and vanisheth away; so he that goeth down to the grave shall come up no more. (Job 7.5, 9)Thel knows that she too will be “consumed,” to become “at death the food of worms” (3.23, 25). The Cloud offers Thel the wise counsel of acceptance. Though he will “vanish and [be] seen no more” he assures her that when he passes away he goes “to tenfold life.” If worms should consume her flesh, the Cloud exclaims, “How great thy use, how great thy blessing!” (3.26). For, he tells her, “Every thing that lives / Lives not alone nor for itself” (3.26-27). The emblem “What is Man!” shows two worms (illus. 13): one realistic, crawling in an arc down an oak-leaf, the other with the face of a sleeping child, lying face upwards on an adjoining leaf, chrysalis-like in swaddling bands. In the Book of Thel the helpless Worm appears to Thel “like an infant wrapped in the Lilly’s leaf” (4.3), and is shown in just this way on plate 4. It cannot speak, but cries like a baby. Thel expresses compassion at its helplessness—“[There is] none to cherish thee with mother’s smiles” (4.6)—and indeed the cries of the infant do raise the “pitying head” of the motherly Clod of Clay (illus. 15).

The Clod of Clay “bow’d over the weeping infant and her life exhal’d / In milky fondness . . .” (4.8-9). This last personage of the poem attains the ultimate degree of selflessness, willingly giving her life as well as her substance for the Worm.43↤ 43 Compare “The Clod and the Pebble”: “Love seeketh not Itself to please, / Nor for itself hath any care, / But for another gives its ease . . . So sang a little Clod of Clay / Trodden with the cattle’s feet . . .” (Songs of Experience, E 19). She echoes the Cloud’s teaching : “O beauty of the vales of Har! we live not for ourselves” (4.10, E 5). In response to Thel’s “pitying tears” (5.7) the “matron Clay” invites Thel to survey her subterraneous “house,” assuring her “’Tis given thee to enter / And to return: fear nothing . . .” (5.16-17). And Thel accepts the invitation.

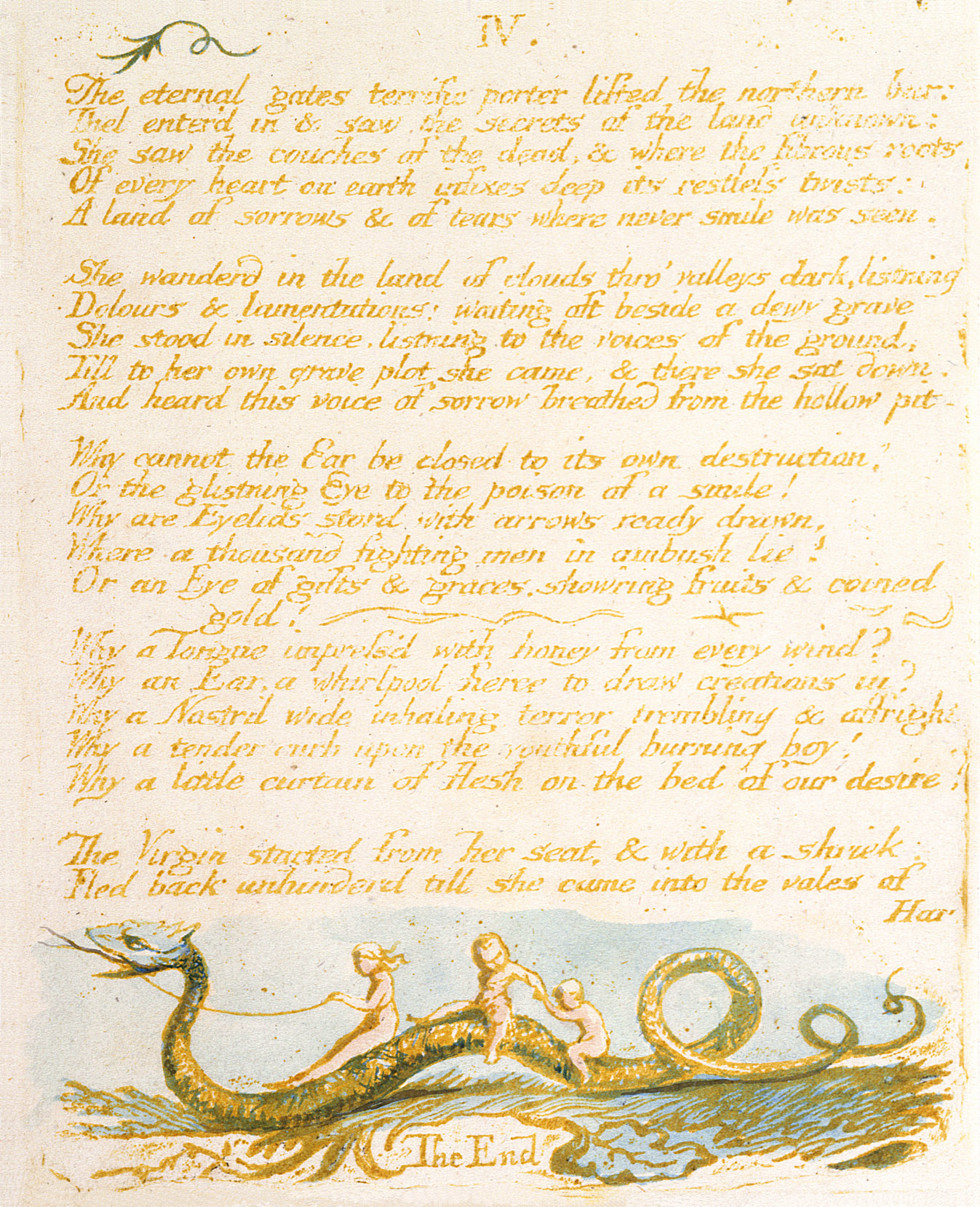

What does she find in the underground realm of Clay? “Couches of the dead” (6.3); tombs such as the grand monuments Blake had sketched fifteen years earlier, as a young apprentice, in Westminster Abbey.44↤ 44 The sketches of royal tombs done in Westminster Abbey during the period 1774-77 are among Blake’s earliest extant drawings. Butlin 1: 1-14, 2: pls. 1-47. In this “land of sorrows & of tears” Thel sees “Vegetated bodies” like that of Daphne, for there “the fibrous roots / Of every heart on earth infixes deep its restless twists” (6.3-5). Like the Lady in Comus, who finds no shelter “from the chill dew, amongst rude burs and thistles” (Comus 351), Thel strays, unprotected and unguided, about the thorny undergrowth of the fallen world45↤ 45 On page 58 of the Notebook, Blake made a sketch which may be an illustration to Comus 350-54. (illus. 16). She enters a region (described by the Elder Brother in Comus) where “thick and gloomy shadows damp” are “oft seen in charnel-vaults, and sepulchres / Lingering, and sitting by a new-made grave, / As loth to leave the body that it loved . . .” (Comus 469-72). Blake depicts Thel wandering

. . . in the land of clouds thro’ valleys dark, list’ningAt last she comes to her own grave-plot, where a “voice of sorrow breathed from the hollow pit” (6.10). The voice Thel hears is potentially her own, moaning from the depths of the grave after the ending of a life-in-possibility to which the maiden has not yet committed herself. This potential self laments the painful intensity of the experiences of each of the senses in earthly life:

Dolours and lamentations; waiting oft beside a dewy grave

She stood in silence, list’ning to the voices of the ground. . . .

(Thel 6.6-8, E 6)

Why are Eyelids stord with arrows ready drawn,begin page 112 | ↑ back to top At its climax the agonized murmur articulates the anguish of the sexual sense of touch: the pangs of desire frustrated, the greater torment of desire satisfied—the agony of self-realization in earthly life that awaits the virgin whose name means “desire”:

Where a thousand fighting men in ambush lie? . . .

Why a Tongue impress’d with honey from every wind?

Why an Ear, a whirlpool fierce to draw creations in?

Why a Nostril wide inhaling terror trembling & affright? (Thel 6.13-18)

Why a tender curb upon the youthful burning boy!At this, Thel rushes “with a shriek” back to the “vales of Har.” She flees the precepts of teachers who affirm that commitment to earthly life demands a continual sacrifice of selfhood. Experiential existence in the fallen world is a course to inevitable destruction, marked by the fierce suffering and terror her own disembodied voice describes. Rather than face that, Thel —who prayed that she might live in “gentleness”—chooses not to enter into it at all.46↤ 46 Wagenknecht relates Thel’s concern about transiency to her “sexual anxiety,” commenting that “She wants to sleep ‘the sleep of death’ (so long as it comes gently), and her sexual misgivings are deflected into concern for the fading of other innocents and into the imagery of God walking in his Garden in the evening time” (155).

Why a little curtain of flesh on the bed of our desire? (Thel 6.19-20)

Thel’s “Motto,” in most copies a kind of postscript to the poem, suggests that Thel might have learned more from her brief sojourn in the “house of Clay” than she allowed herself to do:

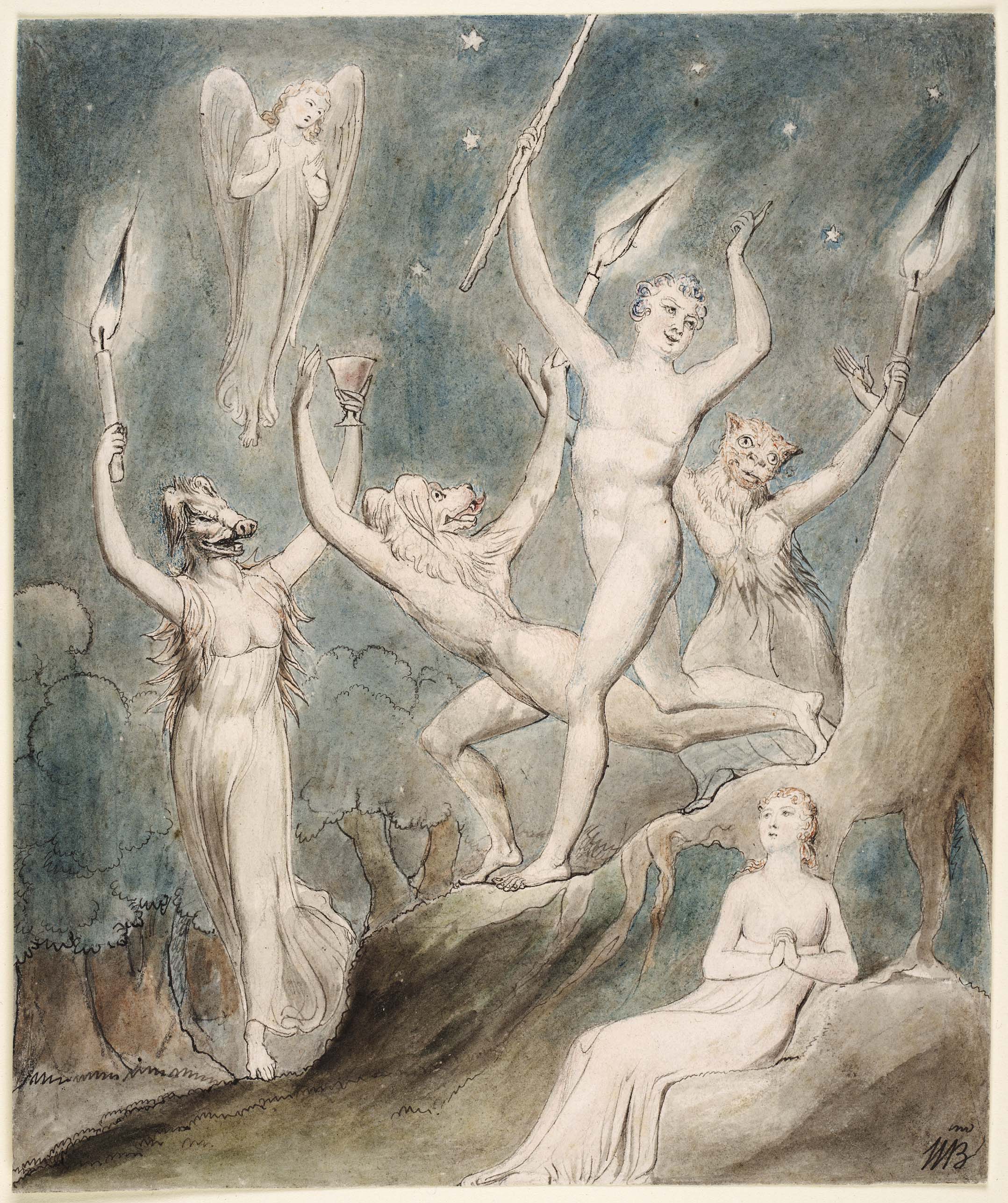

Does the Eagle know what is in the pit?The Mole, the earth-dweller, knows “what is in the pit,” and may also be a symbol of the regenerative potential within experience.47↤ 47 Rodger L. Tarr proposes this view (193). The Eagle, inhabiting the sky and aspiring always in Blake’s work to the visionary realm, knows nothing of the realm of Clay. The “rod” and “bowl” may at one level be reminders of the charming-rod and the cup of Comus (illus. 4); a rod may be a symbol of authority or of the phallus, a bowl may represent the Holy Grail or be a symbol of the womb. Blake obviously intends no simple answers to the four rhetorical questions in “Thel’s Motto.” All Thel can do is look in the direction these questions point. They direct her (and the reader) to the indisputable value of such experience of the skies and the earth as may be gained respectively by the Eagle and the Mole from their diametrically opposed perspectives and “contrary” ways of life. And they question the validity of a distinction between Love and Wisdom: “. . . love indeed is Esse and wisdom is Existere for love has nothing except in wisdom, nor has wisdom anything except from love. Therefore when love is in wisdom, then it exists.”48↤ 48 Swedenborg, Divine Love and Wisdom 14: 7.

Or wilt thou go ask the Mole?

Can Wisdom be put in a silver rod?

Or Love in a golden bowl? (i.1-4, E 3)

Blake commented on this passage of Swedenborg’s Divine Love and Wisdom: “Thought without affection makes a distinction between Love & Wisdom, as it does between body & Spirit” (E 603). His annotation indicates that he regards the division between Love and Wisdom in the same light as he does that “between body & Spirit”—as a notion “to be expunged.”49↤ 49 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell 14, E 49.

The illumination with which Blake concludes the Book of Thel depicts Thel’s choice quite clearly, and incidentally suggests the source of his inspiration in Milton’s work. Plate 6 shows three children—a girl and two younger boys—riding a dragon-headed serpent who coils across the width of the page over the legend “The End” (illus. 17). They cannot be identified from the text of Thel (or from that of America, where Blake was to use the same motif again [illus. 18]); and indeed, in their first appearance, on the final plate of The Book of Thel, they may represent the Lady and the Elder and Younger Brothers of Milton’s Comus, shown almost in babyhood. Perhaps, in one of the several possible meanings of the configuration, these figures embody the desire of both Thel and Milton’s Lady to retreat towards the security of infancy—reversing the natural process of growth through adolescent sexuality into maturity. With the girl astride and holding the reins, the three children ride the seemingly tractable serpent—symbol of man’s fall—without fear.50↤ 50 Wagenknecht (121) discusses this motif as it appears in both the last plate of Thel and in pl. 11 of America, relating it to similar motifs in the “Lyca” poems of the Songs. He restates the questions it raises (158-59), but finds no final answers. Back they gallop, in a leftward or “sinister” direction, to “the vales of Har,” where the phallic serpent has no visible sting, in a paradise apparently

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

In a fallen Paradise continually laid waste by the depredations of Time, Thel laments

that she and every form of living beauty about her must yield to this “Great enimy.”51↤ 51 The Faerie Queene

3.6.39.1. She longs to hear “the voice / Of him that walketh in

the garden in the evening time” (1.13-14), not in wrath, but “gentl[y].”52↤ 52 Cf. Paradise Lost

10.92-99:

Now was the sun in western cadence low

From noon, and gentle airs due

at their hour

To fan the earth now waked, and usher in

The evening cool when

he from wrath more cool

Came the mild judge and intercessor both

To sentence

man: the voice of God they heard

Now walking in the garden, by soft winds

Brought to their ears, while day declined. . . .

Wagenknecht, while citing the

evidence from Tiriel for “the usual view that Thel unambiguously

retreats from life at the end of her poem” (151), argues that “Thel’s return to the

‘vales of Har’ from the grave which the matron Clay has shown her in a moment of vision

cannot be construed as a return to an unreal Beulah, but only as a return to ordinary

fallen existence, an ambiguous retreat, perhaps, from both the horror of the grave and

from the passionate intensity of her response to that horror” (150). Wagenknecht’s

suggestion, which is consonant with his reading of Thel, implies that

Thel’s longing for “gentle” experience (1.12-14, E 3) may be a rejection of the

commitment to romantic “intensity” urged, for instance, in Blake’s poem “Day,” in which

the sun of creativity arises with “wrath increast . . . Crownd with warlike fires &

raging desires” (3-5, E 473)—an obvious “contrary” to the “judge and intercessor” who

comes as the sun sets, without wrath “to sentence man” to a life depleted of visionary

experience in a fallen world. The “Lilly of the valley,” herself a “gentle maid,” assures Thel

that, little and weak and ephemeral though she is, “Yet am I visited from heaven, and he

that smiles on all. / Walks in the valley and each morn over me spreads his hand . .

.”(1.19-20).

When her brief life in time is over the “Lilly” is blessed with the certainty that she will “flourish in eternal vales.” The Cloud directly addresses Thel’s fear that “like a faint cloud kindled at the rising sun / I vanish from my pearly throne . . .” (2.11-12). Although, he says, “I vanish and am seen no more,” yet “when I pass away / It is to tenfold life, to love, to peace and raptures holy . . .” (3.10-11). Thel knows that the Worm begin page 113 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Works Cited

Bateson, F. W., ed. Selected Poems of William Blake. London: 1957.

Bindman, David, comp. and annot. The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. New rev. ed. Garden City: Anchor-Doubleday, 1982. (Cited throughout as E, followed by the page numbers.)

—. The Notebook of William Blake: A Photographic and Typographic Facsimile. Ed. David V. Erdman with the assistance of Donald K. Moore. Oxford: Clarendon, 1973.

—. Complete Writings. Ed. Geoffrey Keynes. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1966.

Burke, Edmund. Reflections on the Revolution in France. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1929.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols., New Haven: Yale UP, 1981.

Damon, S. Foster. “Blake and Milton.” The Divine Vision: Studies in the Poetry and Art of William Blake. Ed. Vivian de Sola Pinto. London: Victor Gollancz, 1957.

—. A Blake Dictionary. London: Thames and Hudson, 1965.

Dunbar, Pamela. William Blake’s Illustrations to the Poetry of Milton. Oxford: Clarendon, 1980.

Erdman, David V. Blake: Prophet Against Empire. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977.

Erdman, David V., annot. The Illuminated Blake. London: Oxford UP, 1975.

Gleckner, Robert F. Blake and Spenser. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1985.

begin page 114 | ↑ back to topThe Holy Bible, Authorized Version (1611). New York, American Bible Society, 1967.

Keynes, Geoffrey, comp. and annot. Engravings by William Blake: The Separate Plates. Dublin: 1956.

—. Drawings of William Blake. New York: Dover, 1970.

Milton, John. The Poems of John Milton. Ed. John Carey and Alistair Fowler. London: Longmans, Green, 1968.

Pinto, Vivian de Sola, ed. Studies in the Poetry and Art of William Blake. London: Victor Gollancz, 1957.

Raine, Kathleen. Blake and Tradition. 2 vols. Bollingen Series Princeton: Princeton UP, 1968.

Shakespeare, William. The Complete Works. Ed. Peter Alexander. London: Collins, 1951.

Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Ed. A. C. Hamilton. London: Longman Group, 1977.

Swedenborg, Emmanuel. Angelic Wisdom concerning the Divine Love and Wisdom. Trans. Clifford and Doris H. Harley. London: Swedenborg Society, 1987.

Tarr, Rodger L. “‘The Eagle’ versus ‘The Mole’: The Wisdom of Virginity in Comus and The Book of Thel.” Blake Studies 3 (1971): 187-94.

Tayler, Irene. “Blake’s Comus Designs.” Blake Studies 4 (1972): 45-80.

Wagenknecht, David. Blake’s Night. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1973.

Werner, Bette Charlotte. Blake’s Vision of the Poetry of Milton. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell UP, 1986.