review

John Heath, The Heath Family Engravers 1779-1878. 2 vols. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1993. Vol. 1, James Heath A.R.A.: 242 pp. + 20 illus. Vol. 2, Charles Heath[,] Frederick Heath [and] Alfred Heath: 351 pp. + 20 illus. $149.95.

Query: Identify the English line engraver who was born in 1757, established his early reputation by engraving Thomas Stothard’s illustrations for The Novelist’s Magazine, published his own separate prints and illustrated books, signed a testimonial for Alexander Tilloch’s method to prevent banknote forgeries, used several innovative graphic techniques including a relief-etching process, and engraved a large panorama of Chaucer’s pilgrims on their way to Canterbury?

Choose one: a. William Blake

b. James Heath

c. both of the above

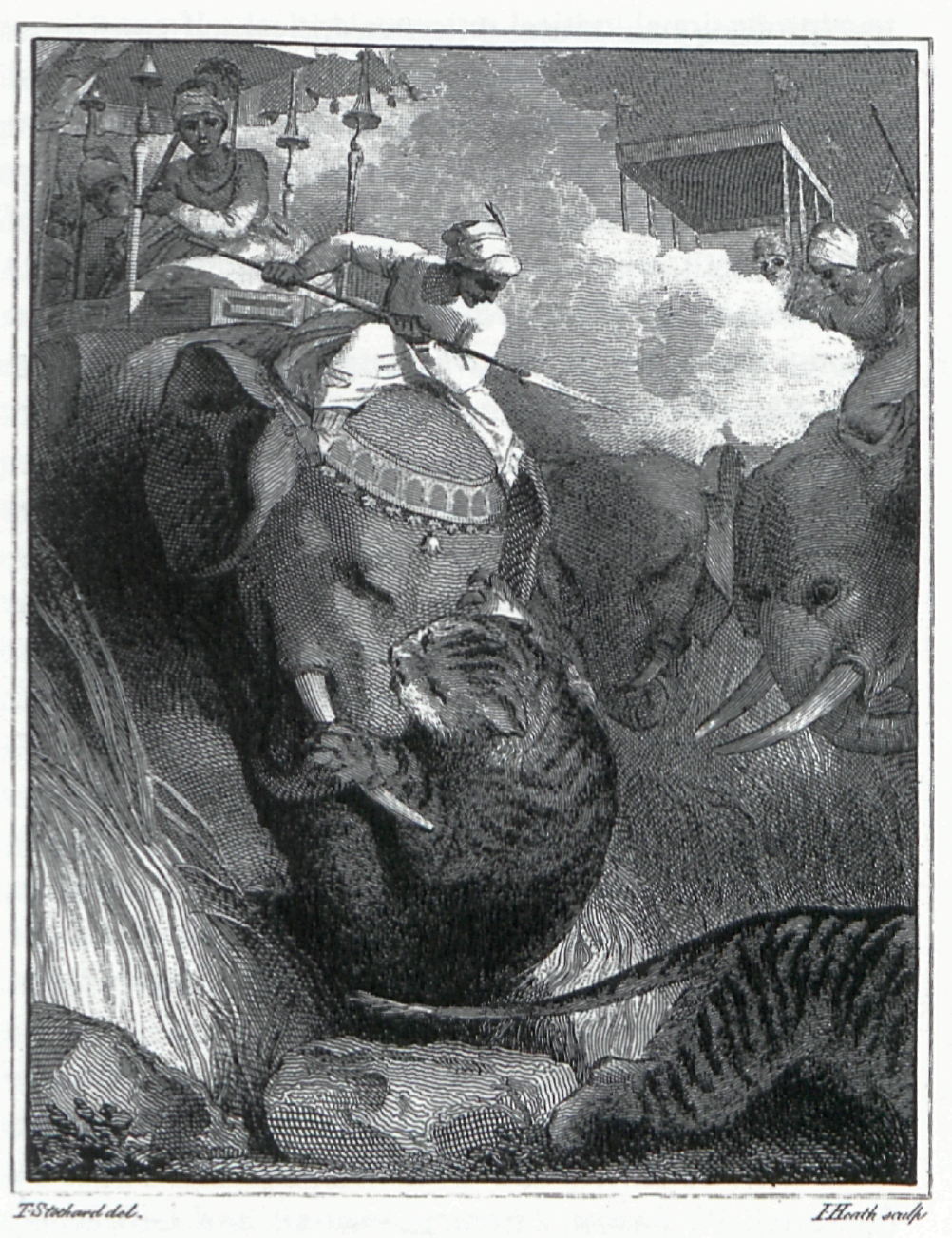

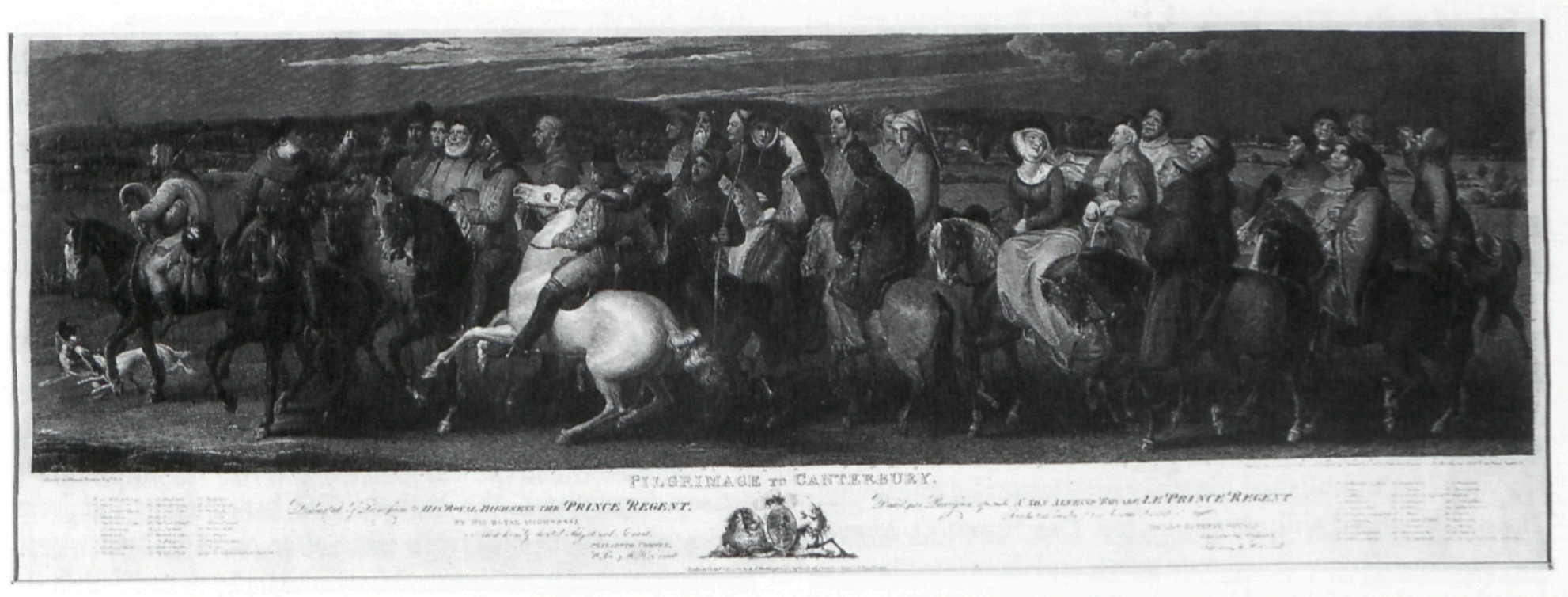

As any good test-taker can guess, the answer is c. A few of these parallels in the lives of Blake and Heath are historical accidents, yet several indicate that some of the more striking features of Blake’s career are not singular eccentricities but responses to imperatives felt by others in his profession. To publish one’s own prints, or books of prints, made sense to both men as a way of eliminating distributors standing between the engraver and the consumer. Self-publication allowed the artisan to exercise more control over the product and to either lower prices or capture the profits that would normally accrue to another party. Blake began to publish his own prints no later than 1784 during his partnership with James Parker. Heath, somewhat slower off the mark (because more successful as a journeyman?), began to co-publish his prints with J. P. Thompson in 1796 (1: 21).1↤ 1 Parenthetical references (by volume and page) are to the book under review. Blake’s plunge into book publishing began with his illuminated books, first produced c. 1788 but not known to have been advertised to the public until 1793. Heath published his edition of Shakespeare, with letterpress text and illustrations by Stothard and Henry Fuseli engraved by Heath, in 1802 (1: 23). Besides these attempts to alter the normal patterns of print distribution, both engravers tried to keep up with, or leap ahead of, innovations in print production. Heath never indulged in anything as radical or unfashionable as relief or white-line etching, but he did develop new techniques for stipple engraving (1: 10) and co-published the first British lithographs in 1803 (1: 24).2↤ 2 In its earliest years, lithography (or “polyautography,” as it was then called) included etching the stone to leave the image in shallow relief. The signature “I Heath sc” appears on the lithographed title page to the 1803 Specimens of Polyautography (1: 24), and thus Heath was one of the first English artists to use the new process invented by Alois Senefelder in Germany (1: 24). Both men sought a commercial success with their Chaucer engravings—Blake’s after his own design, Heath’s after Stothard (illus. 1). As in so many of their other endeavors, Heath was the better businessman, although he too fell upon hard times late in life.

The preceding excursion into career comparisons and what they tell us about the economics of engraving is made possible by the publication of The Heath Family Engravers by John Heath, a retired British diplomat and the great-great-great-grandson of James. The book is no mere family memoir, but a work of dedicated historical scholarship. Like his artisan forefathers, the author is all business—in at least two senses. Facts spill from page after page; indeed, a few family anecdotes, true or not, would have enlivened matters. And most of these facts deal with the business of engraving and publishing. As John Heath is quick to point out, he saw his task as “not so much to assess the claims of the Heath family engravers as artists in their own right as to set them and their activities against the literary, artistic and cultural background of their time, especially as seen through the eyes of their contemporaries” (1:9-10). The result might be called Heath Records, in imitation of Bentley’s Blake Records. John Heath is a very reticent author/editor who allows documents to speak for themselves. Even the first two pages of the “Introduction” to volume 1 are a string of quotations with a minimum of editorial glue to hold them together. Such an approach, when applied to an artist about whom (unlike Blake) so little has been published, has both virtues and limitations. The Heath Family Engravers offers no rationale for its demands on our attention or a point of view from which undigested facts can be made meaningful. Yet, these two volumes can serve for years to come as a source of information and provide the foundation for studies more dedicated to interpretation.

John Heath has been an assiduous researcher and collector of engravings by the Heath family. Much of his information is based on manuscripts or fairly obscure publications, but in a few instances, one wishes for more thorough documentation. Heath claims, for example, that “by long established custom . . . an engraver was entitled to keep twelve copies of first proofs, or buy in others from the publisher at a discount, and then sell them if he wished to collectors at much higher prices than mere ‘common’ impressions” (1: 42). If this practice was as widespread as Heath implies, then it might explain why some plates, such as Blake’s “Beggar’s Opera” after Hogarth and his “Tornado” begin page 68 | ↑ back to top

The two volumes are similarly organized into a cluster of short chapters (such as “The Engraver and His Trade,” “James Heath’s Techniques and Relationships,” and “Charles Heath’s Contribution to Steel Engraving”) followed by a catalogue of engravings by James (vol. 1) and Charles Heath (vol. 2). Unfortunately, there is no “Preface” to explain the organization of the book or the methods of citation used. Odder still is the absence of number or letter designations for the 40 interesting, if rather murky, illustrations. These float in two clusters in the midst of each volume without coordination—indeed, without the means for coordination—between picture and word, even though several of the engravings reproduced are mentioned in the text.

The bulk of both volumes is comprised of the two main catalogues, with much briefer listings for Charles’s sons, Frederick and Alfred, in volume 2. This was clearly a labor of love for the author and is based in large part on his own collection. Information is arranged chronologically in tables, a format that is easy to use but which creates large, unprinted stretches of paper. Could a more economical arrangement have reduced the high cost of the book? Although a good many separate plates are listed, the catalogues are dominated by book illustrations. Only a minimal amount of information is recorded: title, author, publisher, and the artist(s) who designed the illustrations; number, subject (very brief), and binding location of the plates engraved by a member of the Heath family. Measurements are rounded to the nearest centimeter—a rather generous tolerance for small plates. The states of the plates and their inscriptions are not recorded. Each set of tables is designated as a “Catalogue Raisonné.” “Handlist” would be a more appropriate title.

While Blake enthusiasts will find the career of James Heath of primary interest, the life of his son Charles should not be neglected. He too had a taste for innovative graphic techniques, as indicated by his execution, in 1820, of the first book illustration engraved on steel (2: 21). Five years later he combined this high-finish medium with the new and popular genre of the annual gift book to produce the first number of The Keepsake. Although the rage for such prettily bound and embellished volumes soon died down, Charles Heath continued to publish his until 1848. While the stylistic distance between The Book of Urizen and The Keepsake could hardly be greater, Blake’s illuminated books and Heath’s annual emerged from a shared economic dynamic that led both engravers to become book publishers. Near the end of his career, Blake contributed a fine engraving of his design, “Hiding of Moses,” to the short-lived annual Remember Me! (1825-26).

The careers of Charles Heath’s two sons, Frederick and Alfred, are dealt with in a single chapter of six pages. They attempted to continue the family profession well beyond its heyday as a major technology for the reproduction of pictorial images. The traditional art of line engraving on metal plates clung to an aestheticized afterlife well into the second half of the nineteenth-century. Yet its demise as a reproductive craft may have been the necessary prelude to the so-called “Etching Revival,” the return to traditional graphic processes as a means of original artistic expression—as it had been for Durer, Rembrandt, and Blake.

I must confess to a predisposition to like any book written by a fellow collector of British prints. I am quick to forgive errors committed by writers of print catalogues in the hope of receiving similar treatment when my own efforts in that genre are scrutinized. I admire from afar the noble tradition of British amateur—in the best sense of the begin page 69 | ↑ back to top word—scholars, a group that includes my friends Raymond Lister and the late Sir Geoffrey Keynes. Yet, in a book so dedicated to the recording of fact, we can reasonably demand a higher level of accuracy and consistency than what I have found in John Heath’s work. Everything in the book about California and its citizens is wrong: the Huntington Library is in San Marino, not “Pasadena” (1: 67); the Getty Museum Library is in Santa Monica, not “San Marino” (1: 67); R. N. Essick is the author of William Blake Printmaker, not “Essick, G. N.” (1: 58); London Bridge now spans a ditch dug next to the Colorado River in Arizona, not “Lake Tahoe [10 miles wide, 1645 feet deep] in California” (2: 18). Less amusingly but more dangerously, Heath lists two books by A. C. Coxhead, “Thomas Stothard, R.A., An illustrated monograph (A. H. Bullen, London, 1906)” (1: 57), and “Life of Stothard (1919)” (1: 58). The former is well known to those who study Thomas Stothard; the latter is either a work unknown to any other bibliography I have consulted or a misleading reference to Coxhead’s Thomas Stothard: His Life and Work (London: Sidgwick, 1909). These two entries also indicate Heath’s inconsistency in the amount of information he provides, both in his bibliographies of works consulted and in the catalogues of books with plates by the Heath family. Such habits can create confusion or at least force the reader to guess at what is actually meant. The sixth footnote to chapter 3 in volume 1 refers to “Graves: Boydell, p. 178” (1: 54). There is nothing in the “Bibliography” (1:57-59) listed under either “Graves” or “Boydell.” Celina Fox, “The Engravers’ Battle for Professional Recognition in Early Nineteenth Century London,” London Journal 2 (May 1976): 3-31, is recorded as though it were a book without date, place of publication, or publisher: “Fox, Celina. The Engraver’s [sic] Battle for Professional Recognition in Early Nineteenth Century London” (2: 74). “Shenstone’s Poems” (1: 140), without further indication of author or title, is apparently a reference to William Shenstone, The Poetical Works (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1798). Need I point out that it is not nice to change the titles of books listed in what purports to be a “catalogue raisonné”? I remain mystified by a book published by “T. Cadell” in 1788 recorded as having the title “Mina.” (1: 106, no author given).

The introductory essays contain some minor errors (e.g., the small Boydell Shakespeare plates are not “identical” in subject to the larger plates [1: 19]) and what would seem to be either a very large mistake or a major Blake discovery. The passage (1: 31) is worth quoting in full:

As for his [James Heath’s] style, he was essentially a realist engraver, who would probably have disagreed with Blake’s assertion as it stands that ‘Engraving varies so much in the means of expressing the same objects that lines become the language of colours (which is the great object of the engraver’s study)’.

Since no other “Blake” is referred to in John Heath’s book, I took this to mean William Blake. I was immediately startled by Blake’s quoted comment; it was not familiar to me and seemed, on the face of it, most unBlakean. A claim that lines should be used to create a “language of colours” goes against the grain of Blake’s ringing statements, in his Public Address and elsewhere, about the superiority of line to color. When and in what context did Blake write a line that might force a major revision in my sense of his aesthetics? A superscript “12” follows the sentence quoted above; this refers us to “Godfrey, p. 47” (1: 53). The only work listed under “Godfrey” in the Bibliography (1: 58) is Richard T. Godfrey’s well-known study, Printmaking in Britain: A General History from Its Beginnings to the Present Day (Oxford: Phaidon, 1978). I can find no such quotation attributed to Blake anywhere in Godfrey’s book. Nor can I find this statement in the Blake Concordance. Another ghost in the making?

Just before reading The Heath Family Engravers I finished another study of late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century engraving, Morris Eaves’s The Counter-Arts Conspiracy: Art and Industry in the Age of Blake (Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1992). The contrasts between these two books could not be bolder: English/American, amateur/professional, begin page 70 | ↑ back to top critical reticence/critical self-consciousness, praxis/lexis, fact/meaning (the intellectual equivalent of the raw and the cooked?). Unfortunately, there is all too frequently another split, one between inaccuracy/accuracy in the recording of facts. Yet John Heath’s book will be of lasting benefit, even if we can’t believe (or quite figure out) everything he says. Those who read both books can put into practice the lessons in creative contrariety we have learned from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Appendix: Unrecorded Book Illustrations by Thomas Stothard

The Heath Family Engravers includes, in its catalogues of prints by James and Charles, several books with illustrations by Stothard that have not been noted in previous accounts of that artist’s work.3↤ 3 A. C. Coxhead, Thomas Stothard, R. A.: An Illustrated Monograph (London: A. H. Bullen, 1906); Shelley M. Bennett, Thomas Stothard: The Mechanisms of Art Patronage in England circa 1800 (Columbia, Missouri: U of Missouri P, 1988); G. E. Bentley, Jr., review of Bennett, Blake 23 (1990): 205-09. These new titles are listed below. Whenever possible, I have supplemented John Heath’s entries with information garnered from other bibliographies or inspection of the volumes. I am grateful to James Stanger for his assistance in searching the Eighteenth-Century Short Title Catalogue (ESTC).

The Amaranth (London: Renshaw and Co., nd). According to Heath, at least 1 pl. by Charles Heath after Stothard. Heat indicates that this is the work dated to 1836 by Frederick W. Faxon, Literary Annuals and Gift Books (Pinner, Middlesex: Private Libraries Association, 1973) 81. No copy seen.

The Bioscope, or Dial of Life (London: John Murray, 1814). According to Heath, the title page (or a vignette on it?) is engraved by Charles Heath after Stothard. No copy seen; Heath’s information based on an unbound impression in the Royal Academy.

Bishop, Henry Rowley. A Selection of Popular National Airs (Dublin: J. Power, 1820). According to Heath, 2 pls. by Charles Heath after Stothard. NUC lists an 1820 ed. published by J. Power in London. No copy seen.

Blane, William. Cynegetica; or, Essays on Sporting. . . . To which is added, The Chace: A Poem. By William Somerville (London: John Stockdale, 1788). Frontispiece (Illus. 2) and engraved title-page vignette by James Heath after Stothard. Copy in Essick collection.

Brighton, A Poem. A “Frontispiece” (so inscribed) by James Heath after Stothard, known only from a separate impression (Boddington Collection, Huntington Library) with a 6 March 1780 imprint. The title recorded by John Heath is written in pencil (“Brighton a Poem”) beneath the image, with the second and third words lined through in pencil. This is a rather shaky foundation on which to propose the existence of a book of this title. Not in ESTC.

Bruce, James. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, 2nd ed. ([London?]: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1804). According to Heath, 8 pls. by James Heath after Stothard. No copy seen; no Longman ed. listed in NUC or BM cat.

Dangerous Errors ([London?]: T. Relfe, 1822). According to Heath, 1 pl. by Charles Heath after Stothard (information based on unbound impressions in the British Museum and Royal Academy). No copy seen.

Lamb, Charles. Adventures of Telemachus ([London?]: J. Coxhead, 1817). Heath describes 1 pl. by Charles Heath after Stothard as “Shipwreck of Telemachu [sic?].” I can find no such work by Lamb; perhaps an error for his Adventures of Ulysses, first published in 1808 with frontispiece and title-page vignette designed by Henry Corbauld.

Lolme, Jean Louis de. The Constitution of England, 4th ed. (London: G. Robinson and J. Murray, 1784). Frontispiece portrait of de Lolme by James Heath after “Stoddart,” oval, 10.5 × 8.7 cm. (4° × 3 in.). The same plate appears in the “New Edition” of 1789, published by G. G. J. and J. Robinson and J. Murray, and in the “New Edition” of 1790, published by G. Robinson and J. Murray. Copies at the Huntington Library. According to Heath, there is a 1784 ed. published by G. G. J. and J. Robinson, with the portrait measuring 7 × 6 in., and editions of 1789 and 1816 with the same design re-engraved in a larger size (10 × 9 in.). No copies seen with either of these larger versions.

begin page 71 | ↑ back to topMina. ([London?]: T. Cadell, 1788). Heath reports, apparently on the basis of an unbound impression in the British Museum, that this book contains 1 pl. by James Heath after Stothard. No author recorded; no copy seen; not found in ESTC.

Richardson, Samuel. Sir Charles Grandison ([London?]: J. F. Dove, nd). According to Heath, published c. 1824 with 1 pl. by Charles Heath after Stothard. Heath’s information based on an unbound impression in the Royal Academy; no copy seen.

Scott, Walter. The Vision of Don Roderick ([London?]: White and Co., 1812). At least 1 pl. by Charles Heath after Stothard. No copy listed in NUC or BM cat.; information based on unbound impressions (British Museum and Essick collection). Perhaps published in some collected ed. of Scott.

Tatler, The. 6 vols. (London: C. and J. Rivington, C. Bathurst, 1786). According to Heath, at least 3 pls. by James Heath after Stothard. NUC locates a copy in the Huntington Library, but I have not been able to find it. Perhaps the same as the following work recorded in ESTC: [The Tatler]. The Lucubrations of Isaac Bickerstaff. 6 vols. (London: C. Bathurst, J. Buckland, J. Rivington and Sons, W. Owen, R. Horsfield [and 21 others in London], 1786).