minute particular

A Blake Source for von Holst

An important sheet of figure drawings by the English romantic painter Theodor von Holst (1810-44) has recently come to light to reveal Blake as a stronger iconographic source for Fuseli’s pupil than has previously been evident and hence further confirm Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s view of Holst; “. . . in many of whose most characteristic works the influence of Blake, as well as that of Fuseli, has probably been felt.”1↤ 1 Supplementary chapter 39 in A. Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, 1863, 1: 379. Rossetti was Holst’s greatest admirer and the inclusion of this short account of his one-time hero was both testimony to the romantic sympathy that he felt with Holst’s work and the importance that he placed on his role as a disciple of the earlier generation of romantic artists.

As with Fuseli and Rossetti, Holst’s family background was also rooted in continental Europe. His father, Matthias von Holst, had been a professor of music and taught members of the imperial family in St. Petersburg. He returned to Riga with his young Russian wife but, amidst the upheavals of the Napoleonic wars, found that his political ideas had become so unwelcome that he was forced to flee with his family and they settled in London in 1807. Theodor was born there three years later and by the age of 10 his prodigious talent for drawing had attracted the attention of both Fuseli and Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was later criticized for leading Holst astray with commissions for erotic drawings of which several were destined for the portfolios of King George IV.

Holst steadfastly maintained an adherence to the artistic values of his Royal Academy masters throughout his short life but developed his own highly eclectic manner of stylistic and subject improvisation far beyond what was generally acceptable to the changing nature of English patronage during the age of reform. His vivacious, supernatural and daemonic pictures must have made many of the rising middle-class patrons blanch as they strolled along the exhibition walls of London looking for suitable scenes of religious and domestic genres to hang in their sittingrooms. In this way Holst was subjected to the same rejection and neglect begin page 79 | ↑ back to top

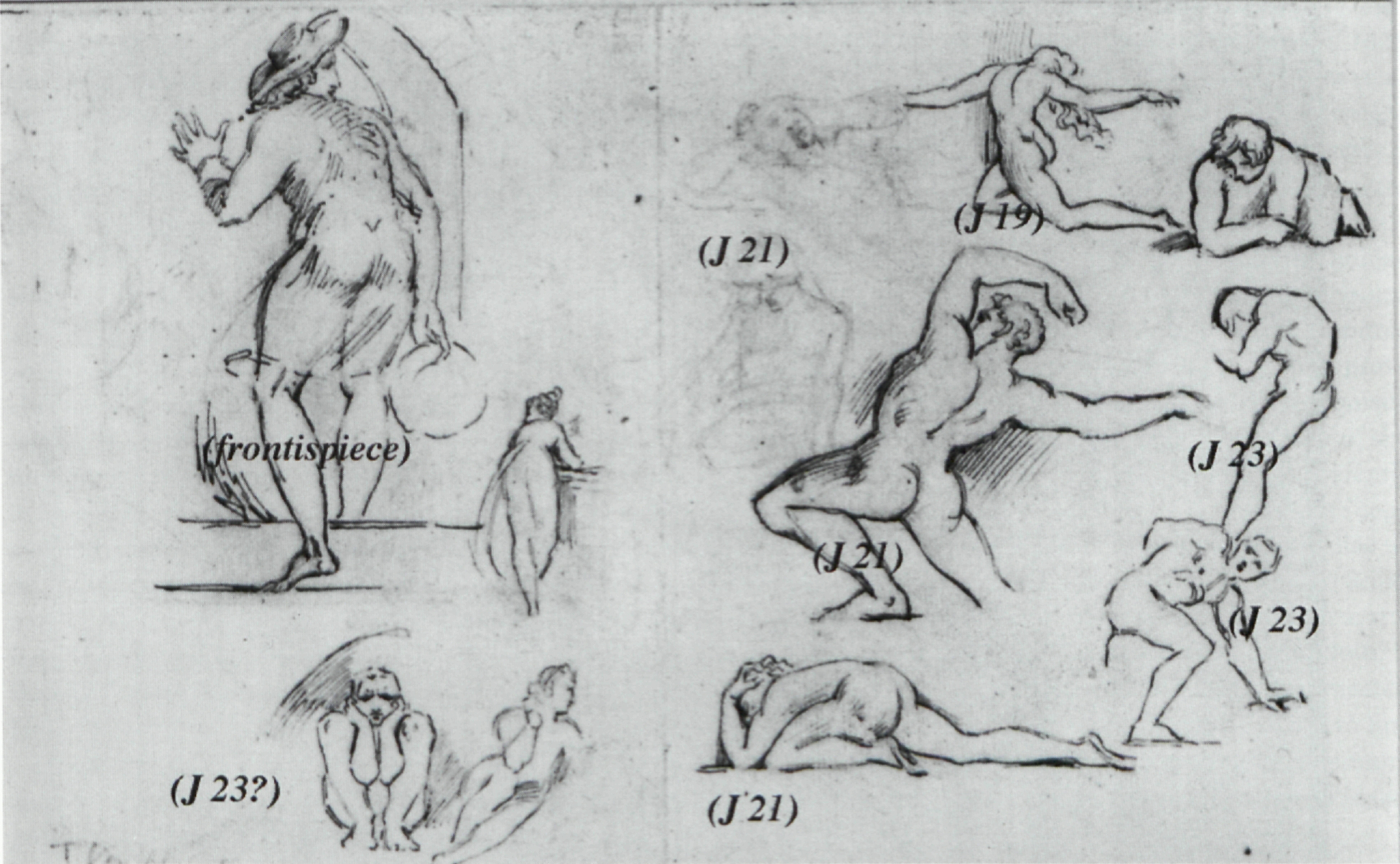

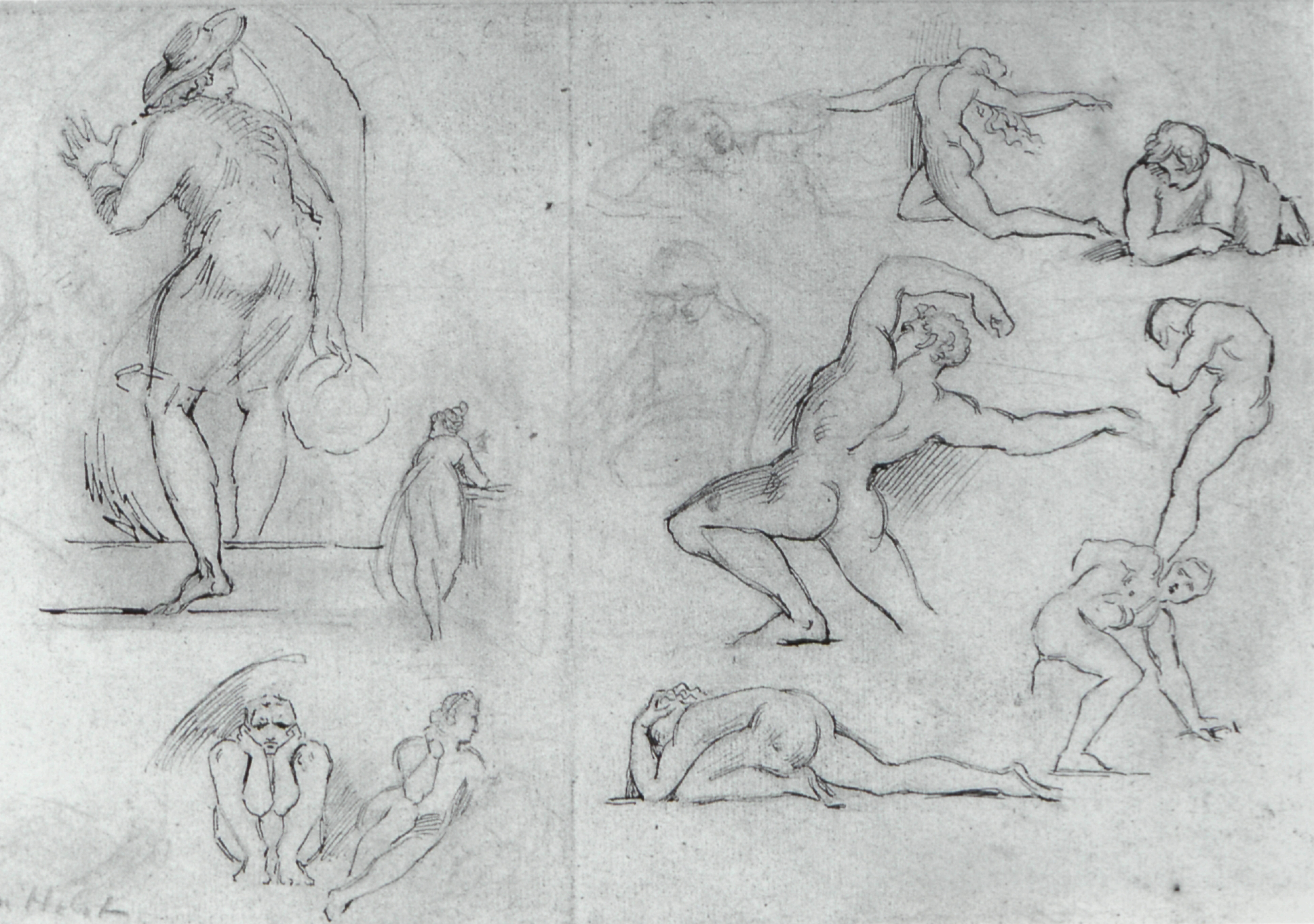

that had affected the reputations of both Blake and Fuseli until their resurrection in the present century.Fortunately a sufficiently representative sample of works had become available for a sesquicentenary exhibition of Holst’s paintings, drawings, and prints to take place last year—at Hazlitt, Gooden and Fox in London and at Cheltenham Art Gallery. Prior to this the very limited knowledge of Holst’s work had greatly hindered both appraisal of him and confirmation of Rossetti’s proposal of Holst as “one of the few connecting links” from the art of Fuseli and Blake to that of the Pre-Raphaelites. My catalogue of the exhibition,2↤ 2 The Romantic Art of Theodor Von Holst 1810-1844, published by Lund Humphries, London 1994 (Distributed in the USA by the Antique Collectors Club). I believe, establishes this connection at last but nevertheless provides only limited evidence of Blake’s influence on Holst. However, subsequent to the exhibition and publication of the catalogue, I was delighted to discover that a group of six drawings by Holst in a private collection in England contains one that establishes this line of influence without a doubt.3↤ 3 All these drawings were orignally contained in the “Rolls Album” which was purchased by Colnaghi’s in 1959 and later dispersed (see Appendix II in my Holst catalogue). This particular sheet appears to have been purchased separately by Peter Pears sometime after the other five drawings were given to Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears by Imogen Holst in the early 1960s. Imogen Holst was the daughter and biographer of the composer Gustav Holst, a great-nephew of the artist. I would like to take this opportunity of offering my warmest thanks to Rosamund Strode for bringing these drawings to my attention and for her most generous and enthusiastic support for the publication of the Holst catalogue last year. As can be clearly seen from the pen and pencil studies on this sheet (illus. 1), the majority of the prominent figures are copies of those from Blake’s Jerusalem. The key to this identification is the well-known figure of Los entering the gothic doorway from the frontispiece plate. The source for at least six further figures can be found in plates 19, 21, and 23 from the first chapter of Jerusalem (illus. 2). Holst has copied these with varying degrees of freedom but their source is unmistakable.

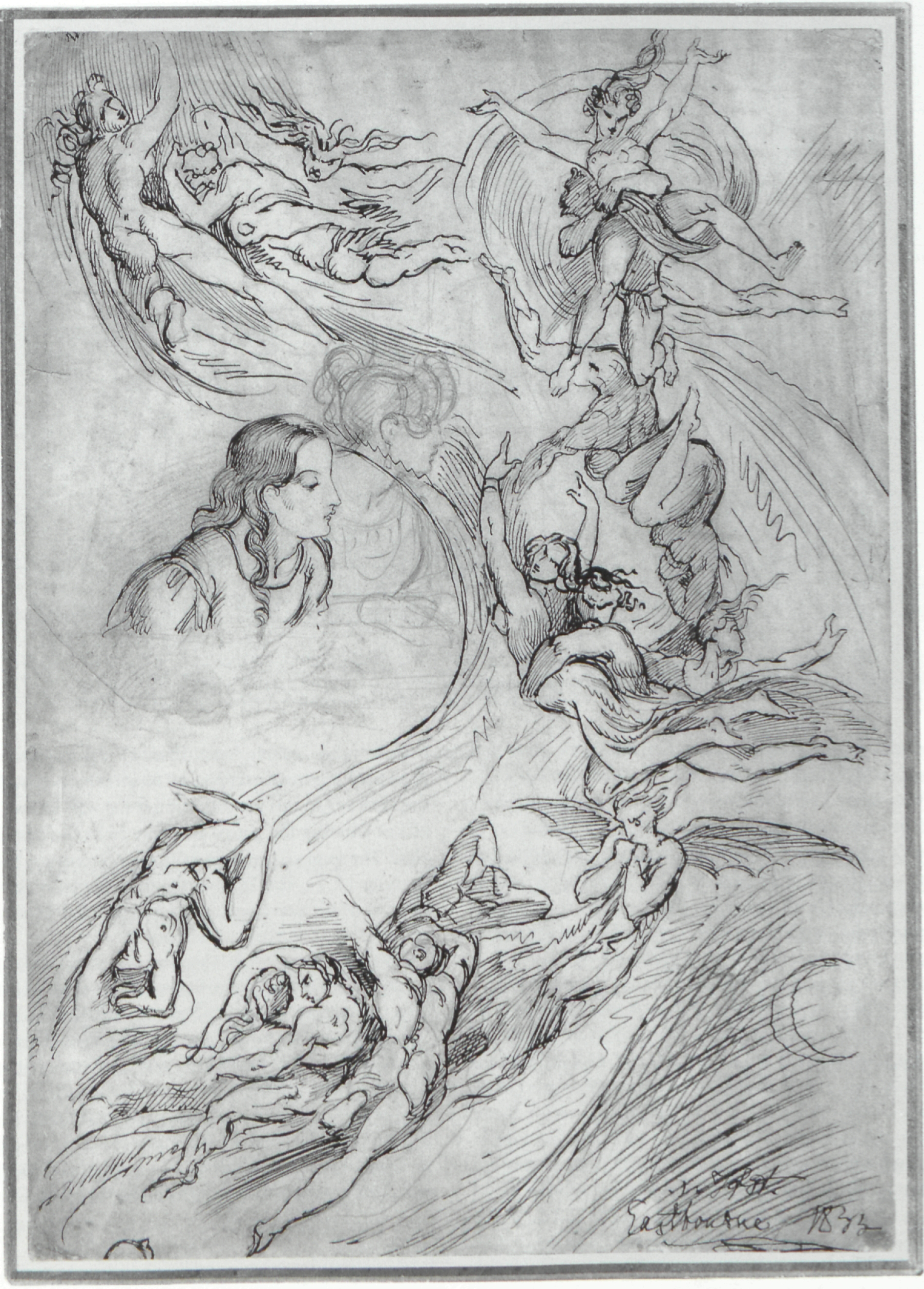

Unfortunately I have not been so successful in identifying the source for several other figures on the sheet of which at least one appears stylistically closer to Fuseli rather than Blake. With regard to the “seated man with his head in his hands,” Martin Butlin has kindly pointed out to me the similarity to Blake’s figure in plate 3 of Europe. Holst was certainly familiar with Europe as can be seen from his borrowing of figures from plates 1 and 9 used in a drawing—known as Dream of Marguerite (illus. 3)—executed in 1833. This was probably while on a visit to his elder brother, Gustavus, begin page 80 | ↑ back to top

Jerusalem is also of special interest since it was the one work by Blake singled out for inclusion in a review for the London Magazine by Holst’s close friend the dilettante artist and writer Thomas Griffiths Wainewright (1794-1847). This characteristically jocular piece appeared in the issue for September 1820 and was considered by Gilchrist6↤ 6 Life of William Blake 1: 278-79. to be a “feeler for a possible subsequent full article on Blake. At this point in time Wainewright was best know under his nom-de-plume as Charles Lamb’s “light-hearted Janus [Weathercock]” and he was still several years away from the suspicion of his criminal activity which included strychnine poisoning and the Bank of England check forgery that finally led to his conviction and transportation “for life” to the penal colony of Hobart, Tasmania in 1837.7↤ 7 For the fullest account of Wainewright see J. Curling, Janus Weathercock, London 1938.

Like Holst, Wainewright was a fervent follower of Fuseli and was also an admirer and patron of Blake. Gilchrist reported that Wainewright had purchased several of the illuminated books among which was one of the finest colored copies of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience and the only known copy of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell embellished with gold.8↤ 8 Ibid. 277. I am grateful again to Martin Butlin for referring me to Joseph Viscomi’s recent study Blake and the Idea of the Book which provides details of Wainewright’s patronage of Blake and his purchase of several of the prophetic books (perhaps with the proceeds from his check forgery in 1826). In addition to Songs of Innocence and of Experience (copy X) and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (copy I), Wainewright’s collection was also know to contain Milton (copy C), a set of proof Illustrations to the Book of Job, Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims and possibly Jerusalem (monochrome copy D). Such admiration was reciprocated in some degree for Blake was recorded as singling out Wainewright’s picture of The Milk-Maid’s Song as “very fine” while walking round the Royal Academy exhibition of 1823 with Samuel Palmer.9↤ 9 Ibid. 278. So, given the strength of these relationships, it seems very probable that it was Wainewright who introduced Holst to Blake’s designs, although several other artist and connoisseur acquaintances of Holst were also friends or patrons of Blake during his last years including John Varley, William Young Ottley and Sir Thomas Lawrence. It would be most desirable to be able to pinpoint which copies of Blake’s designs Holst employed as source material since this could shed further light on their provenance and also the circle of artists that the younger romantic associated with. However the rather free manner of the copying of the present sheet seems to preclude such identification.10↤ 10 However it may be possible to eliminate certain copies of Jerusalem as a source. Morton D. Paley points out several iconographic differences in various copies of the frontispiece design (see Jerusalem, William Blake Trust/Tate Gallery, 1991 [130] and additional plate illus. i-iii) and comparison with Holst’s drawing would seem to preclude colored copy E (Paul Mellon’s Collection) from the running. This is indicated in details such as Los’s finger shapes and non-sandaled feet and the absence of full plate-sized rays emanating from the “globe of Light.” Holst has his copy of this latter detail actually in front of the archway upright and this only appears to occur in colored copy B, although in this case it is not identical and the fingers that hold it are different. However the retouching of the garment and body shape below Los’s left armpit in copy B is closer than the monochrome copies to Holst’s figure as is the more curved shape of Los’s hat brim. Such inconsistency is both puzzling and unfortunately inconclusive at present, particularly as Wainewright appears to have provided the most likely source for Holst but is believed to have owned monochrome copy D (see n8). Of course an alternative possibility may be that Holst was following the copying of another artist as intermediary. This is in marked contrast to some of Holst’s copies after Fuseli which are sometimes almost impossible to distinguish from the original drawings, as the late Gert Schiff discovered when re-attributing the works of both these artists during his monumental work on Fuseli in the 1960s.11↤ 11 See G. Schiff, Echtheits-und Zuschreibungsprobleme bei Johann Heinrich Füssli, Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft, Annual Report, Zurich 1965 and my catalogue, The Romantic Art of Theodor Von Holst.

At present only about a quarter of Holst’s documented work has appeared so far. We can thus look forward to further discoveries in the future with the possibility that more may also contain further evidence of the influence of Blake.