ARTICLE

“Dear Generous Cumberland”: A Newly Discovered Letter and Poem by William Blake

The discovery of a letter by William Blake to one of his more intimate correspondents is a rare and signal event. In the 1960s, two letters to William Hayley came to light. Both, however, had been recorded, with brief summaries and extracts, in a Sotheby’s auction catalogue of 1878.1↤ 1 Catalogue of a Valuable Collection of Autograph Letters, Forming the Hayley Correspondence, Sotheby, Wilkinson, and Hodge, 20-22 May 1878, lot 21, letter of 16 July 1804 (£.3.1s. to Naylor); and lot 26, letter of 4 December 1804 (£4 to Naylor). These two letters were first printed in full in George Mills Harper, “Blake’s Lost Letter to Hayley, 4 December 1804,” Studies in Philology 61 (1964): 573-85; and Frederick W. Hilles, “A ‘New’ Blake Letter [of 16 July 1804],” Yale Review 57 (1967): 85-89. It has been many more decades since a wholly unrecorded letter has emerged. The present essay announces just such a discovery: a previously unknown letter by Blake to his friend of many years, George Cumberland, posted on 1 September 1800, just three weeks before Blake and his wife Catherine moved from the London suburb of Lambeth to Felpham on the Sussex coast. This letter was first brought to the attention of Morton D. Paley by its previous owner, a private British collector, in the summer of 1997. With the help of the San Francisco dealer John Windle, the letter was acquired by Robert N. Essick in November of the same year. A transcription follows:

[addressed as follows]PS. I hope to be Settled in Sussex before the End of September it is certainly the sweetest country upon the face of the Earth

Mr Cumberland

Bishopsgate

Windsor Great Park

[Written sideways in pencil at left in another hand] Wm. Blake 1800

My Dear Cumberland

To have obtained your friendship is better than to have sold ten thousand books. I am now upon the verge of a happy alteration in my life which you will join with my London friends in Giving me joy of — It is an alteration in my situation on the surface of this dull Planet I have taken a Cottage at Felpham on the Sea Shore of Sussex between Arundel & Chichester. Mr Hayley the Poet is [next 3 words inserted] soon to be my neighbour he is now my friend. to him I owe the happy suggestion for it was on a visit to him that I fell in love with my Cottage. I have now better prospects than ever The little I want will be easily supplied he has given me a twelvemonths work already. & there is a great deal more in prospect I call myself now Independent. I can be Poet Painter & [written over f] Musician as the Inspiration comes. And now I take this first oppor [line break] -tunity to Invite you down to Felpham we lie on a Pleasant shore it is within a mile of Bognor to which our Fashionables resort My Cottage faces the South about a Quarter of a Mile from the Sea, only corn Fields between. tell Mrs Cumberland that my Wife thirsts for the opportunity to Entertain her at our Cottage

Your Vision of the Happy Sophis I have devourd. O most delicious book how canst thou Expect any thing but Envy in Londons accursed walls. You have my dear friend given me a task which I have endeavourd to fulfill I have given a sketch of your Propo[line break] -sal to the Editor of the Monthly Magazine desiring that he will [page ends] give it to the Public hope he will do so. I have shown your Bonasoni to Mr Hawkins my friend desiring that he will place your Proposal to the account of its real author. wherever he goes

How Sorry I am that you should ever be Ill. it also gives me pain to hear that you intend to leave Bishopsgate & it would give me more pleasure to hear that Sussex was preferred by you to Somersetshire But wherever you Go God bless you.

Perhaps I ought to give you My Letter to the Editor of the Monthly Mag. It is this

Sir

Your Magazine being so universally Read induces me to recommend to your notice a Proposal made some years ago in a Life of Julio Bonasoni which Proposal ought to be given to the Public in Every work of the nature of yours. It is. For the Erection of National Galleries for the Reception of Casts in Plaster from all the Beautiful Antique. Statues Basso Relivos &c that can be procured at home or abroad. Which Galleries may be built & filled by Public Subscription To be open to The Public. Their Use would be To Correct & Determine Public Taste as well as to be Treasures of Study for Artists. If you think [page ends] that this Proposal is of the Consequence that it appears to me to be, You will Extract the Authors own words & give them in your valuable Magazine. The Work is Intitled “Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasoni & [next 3 words inserted] by George Cumberland Publishd by Robinsons Paternoster Row 1793

Yours W. B.

begin page 5 | ↑ back to top I so little understand the way to get such things into Magazines or News papers that if I have done wrong in Merely delivering the Letter at the Publishers of the Magazine beg you will inform me

My Wife joins with me in Love & Respect to yourself & familly

I am Your devoted artist

Willm Blake

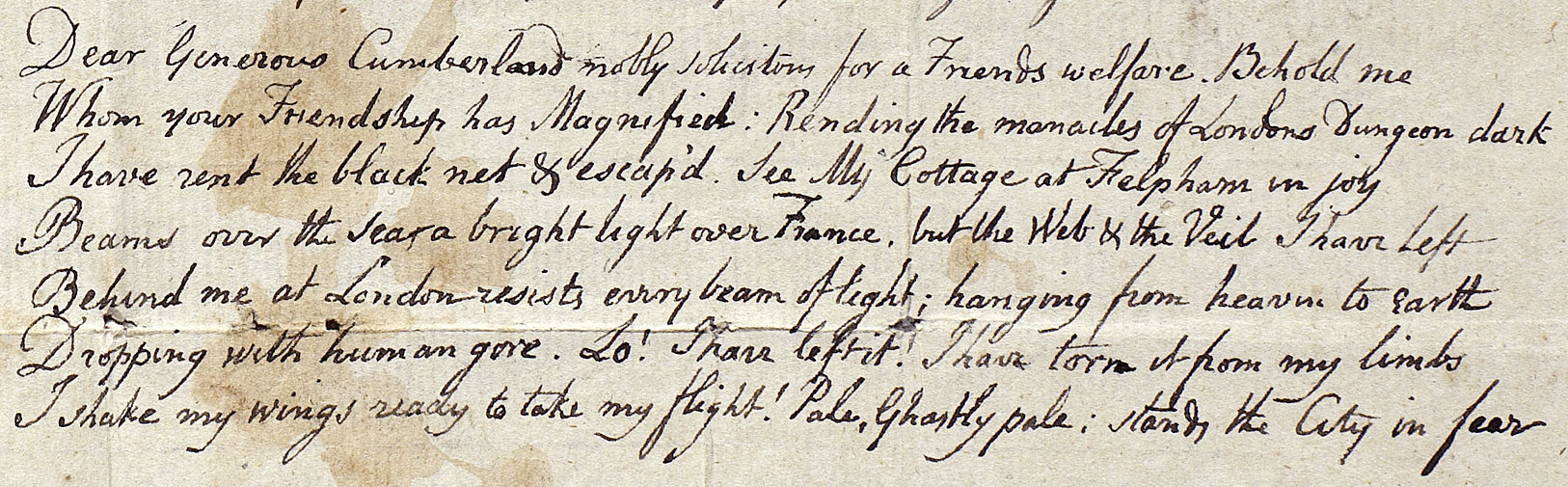

Dear Generous Cumberland nobly solicitous for a Friends welfare. Behold me

Whom your Friendship has Magnified: Rending the manacles of Londons Dungeon dark

I have rent the black net & escap’d. See My Cottage at Felpham in joy

Beams over the Sea, a bright light over France, but the Web & the Veil I have left

Behind me at London resists every beam of light; hanging from heaven to Earth

Dropping with human gore. Lo! I have left it! I have torn it from my limbs

I shake my wings ready to take my flight! Pale, Ghastly pale: stands the City in fear

The subject of this letter was a momentous one for Blake, a change in residence that would begin a new phase of his life. The references to Felpham in this letter are the first to appear in his writings. As is well known, he had decided to move there in order to be employed as an artist and engraver for William Hayley’s various projects, the most important of which was his biography of William Cowper. Blake had come on an extended visit early in July 1800, and by 11 August we find Hayley writing that “the ingenious Blake . . . appeared the happiest of human Beings on his prospect of inhabiting a marine Cottage in this pleasant village. . . .”2↤ 2 Letter to John Hawkins, printed in G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969) 72. This letter was previously published in a book of correspondence by and to Hawkins: I am, my dear Sir. . ., ed. Francis W. Steer (Chichester: privately printed, 1959) 4. In a letter of 12 September, Blake would inform John Flaxman that “every thing is nearly completed for our removal [from] <to> Felpham.”3↤ 3 The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman (Garden City, New York: rev. ed., 1988) 756. This edition is hereafter cited as E.

The move to Felpham was, as we see in Blake’s letter, associated in his mind with artistic independence. He would begin with a commission from Hayley for “a twelvemonths work.” This was probably the series of heads of poets for Hayley’s library, on which Blake reported himself well engaged on 26 November 1800.4↤ 4 Letter to Hayley, E 714. In the event, the 18 heads, interspersed with other projects, may have taken more than a year to complete. Martin Butlin dates them c. 1800-03; see The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981) 1: 297. Interestingly, in this passage Blake confers equal status to his activities as “Musician” to those as poet and painter. This both confirms the importance music had for Blake and establishes that he did compose music, though presumably he did not know musical notation. That Blake wrote music for his poems has long been reported. John Thomas Smith, author of Nollekens and His Times (1828), heard Blake sing his songs early in his career, when he frequented the gatherings of the Rev. and Mrs. Anthony Mathew: ↤ 5 Reprinted in Blake Records 457. Allan Cunningham (1784-1842), who did not know Blake, reported on the basis of an unknown authority that composing music was integral to Blake’s creative process in the later 1780s: In sketching designs, engraving plates, writing songs, and composing music, he employed his time. . . . As he drew the figure he meditated the song which was to accompany it, and the music to which the verse was to be sung, was the offspring of the same moment. Of his music there are no specimens . . . —Blake Records 482, from Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1830).

Much about this time, Blake wrote many other songs, to which he also composed tunes. These he would occasionally sing to his friends; and though, according to his confession, he was entirely unacquainted with the science of music, his ear was so good, that his tunes were sometimes most singularly beautiful, and were noted down by musical professors.5

That Blake did indeed spend some of his time at Felpham as “Musician” when the “Inspiration” came is attested by the Oxford student Edward Garrard Marsh in a letter to William Hayley in which Marsh mentions “The hymn, which inspired our friend, whom I have some idea, I mistitled a poetical sculptor instead of a poetical engraver. . . .” This must refer to Blake, though the hymn that inspired may not have been written by Blake. However, Marsh goes on to say in the same letter: ↤ 6 Original letter in the collection of Robert N. Essick. First published in Essick, “Blake, Hayley, and Edward Garrard Marsh: ‘An Insect of Parnassus,’” Explorations: The Age of Enlightenment 1 (1987): 58-94 (quotation cited from 66). The Blake references in this letter are also quoted in G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records Supplement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988) 18-19.

I long to hear Mr Blake’s devotional air, though I should have been very aukward [sic] in the attempt to give notes to his music. His ingenuity will however (I doubt not) discover some method of preserving his compositions upon paper, though he is not very well versed in bars and crotchets.6begin page 6-7 | ↑ back to top

![Wm. Blake 1800 Mr Cumberland Bishopsgate Windsor Great Park C. 1 SE[PTEMBER 1]800 My Dear

Cumberland To have obtained your friendship is better than to have sold ten thousand books. I am now upon the

verge of a happy alteration in my life which you will join with my London friends in Giving me joy of - It is

an alteration in my situation on the surface of this dull Planet I have taken a Cottage at Felpham on the Sea

Shore of Sussex between Arundel & Chichester. Mr Hayley the Poet is soon to be my neighbour he is now my

friend. to him I owe the happy suggestion for it was on a visit to him that I fell in love with my Cottage. I

have now better prospects than ever The little I want will be easily supplied he has given me a twelvemonths

work already. & there is a great deal more in prospect I call myself now Independent. I can be Poet

Painter & Musician as the Inspiration comes. And now I take this first opportunity to Invite you down to

Felpham we lie on a Pleasant shore it is within a mile of Bognor to which our Fashionables resort My Cottage

faces the South about a Quarter of a Mile from the Sea, only corn fields between. tell Mrs Cumberland that my

Wife thirsts for the opportunity to Entertain her at our Cottage Your Vision of the Happy Sophis I have

devourd. O most delicious book how canst thou Expect any thing but Envy in Londons accursed walls. You have my

dear friend given me a task which I have endeavourd to fulfill. I have given a sketch of your Proposal to the

Editor of the Monthly Magazine desiring that he will](http://www.blakearchive.org/images/lt1sept1800.1.1+2.rm.300.jpg)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

![give it to the Public hope he will do so. I have shewn your Bonasoni to Mr Hawkins my friend

desiring that he will place your Proposal to the account of its real author, wherever he goes How Sorry I am

that you should ever be Ill. it also gives me pain to hear that you intend to leave Bishopsgate & it would

give me more pleasure to hear that Sussex was preferred by you to Somersetshire But where ever you Go God

bless you. Perhaps I ought to give you My Letter to the Editor of the Monthly Mag. It is this Sir Your

Magazine being so universally Read induces me to recommend to your notice a Proposal made some years ago in a

Life of Julio Bonasoni which Proposal ought to be give to the Public in Every work of the nature of yours. It

is. For the Erection of National Galleries for the Reception of Casts in Plaster from all the Beautiful

Antique Statues Basso Reli[e]vos &c that can be procured at home or abroad. Which Galleries may be built

& filled by Public Subscription To be open to The Public. Their Use would be To Correct & Determine

Public Taste as well as to be Treasures of Study for Artists. If you think that this Proposal is of the

Consequence that it appears to me to be, You will Extract the Authors own words & give them in your

valuable Magazine. The Work is Intitled “Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasoni & by George

Cumberland Published by Robinsons Paternoster Row 1793 Yours W.B. I so little understand the way to get such

things into Magazines or News papers that if I have done wrong in Merely delivering the Letter at the

Publishers of the Magazine beg you will inform me My Wife joins with me in Love & Respect to yourself

& familly I am Your devoted artist Willm Blake PS. I hope to be settled in Sussex before the End of

September it is certainly the sweetest country upon the face of the Earth Dear Generous Cumberland nobly

solicitous for a Friends welfare. Behold me Whom your Friendship has Magnified: Rending the manacles of

Londons Dungeon dark I have rent the black net & escap’d. See My Cottage at Felpham in joy Beams over

the sea, a bright light over France, but the Web & the Veil I have Left Behind me at London resists every

beam of light; hanging from heaven to Earth Dropping with human gore. Lo! I have left it! I have torn it from

my limbs I shake my wings ready to take my flight! Pale, Ghostly pale: stands the City in fear](http://www.blakearchive.org/images/lt1sept1800.1.3+4.rm.300.jpg)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

In his sanguine mood, Blake introduces the name of “Mr Hawkins my friend,” indicating the reappearance in his life of someone who had once tried to advance his career in a very significant way. John Hawkins (1758?-1841)was a wealthy art collector and a writer on antiquarian subjects.10↤ 10 DNB 9: 221; and I am, my dear Sir..., ix-xxi. Their original connection was John Flaxman. On 18 June 1783, Flaxman wrote to his wife, Nancy, that Hawkins “at my desire has employed Blake to make him a capital drawing for whose advantage in consideration of his great talents he seems desirous to employ his utmost interest.”11↤ 11 Blake Records 24. Neither this nor any of Hawkins’s other commissions for Blake have been traced. Then, on 26 April 1784, Flaxman reported to William Hayley: “Mr: Hawkins a Cornish Gentleman has shewn his taste & liberality in ordering Blake to make several drawings for him, & is so convinced of his uncommon talents that he is now endeavouring to raise a subscription to send him to finish [his] studies in Rome. . . .”12↤ 12 Blake Records 27-28. Butlin suggests that three outline drawings after Blake that Flaxman drew from memory when in Rome may be based on the pictures mentioned. See The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake 1: 57-8 (no. 152), 2: plate 170. Being a younger son, Hawkins, as Flaxman explained, could not meet the entire expense himself; evidently he was unable to raise the necessary money, and Blake was not to have his time in Rome. Nevertheless, Blake obviously remembered Hawkins’s interest with gratitude, and his fortuitous reappearance must have impressed Blake, always a believer in signs, as auspicious. Hawkins had met William Hayley at the Flaxmans’ in London only in May 1799, and he had then visited Hayley, who addressed a poem to him, at Eartham in September 1799.13↤ 13 See Morchard Bishop, Blake’s Hayley (London: Gollancz, 1951) 243, 245. On 11 August1800, Hayley wrote to Hawkins that “that worthy Enthusiast, the ingenious Blake” would be made even happier if Hawkins should move to Sussex.14↤ 14 Blake Records 72 and n1. As Bentley notes, Hawkins did eventually move to Sussex, but not until 1806. Hawkins was later to be associated in Blake’s mind with one more significant event. Blake’s account of his inner renewal the day after visiting the Truchsessian Gallery is immediately preceded by the words: “Our good and kind friend Hawkins is not yet in town — hope to soon have the pleasure of seeing him, with the courage of conscious industry, worthy of his former kindness to me.”15↤ 15 Letter to William Hayley, 23 October 1804, E 756. For the significance of this linkage, see Morton D. Paley, “The Truchsessian Gallery Revisited,” Studies in Romanticism 16 (1977): 165-77.

Much of the letter is devoted to the projects of George Cumberland, whose friendship with Blake may have begun as early as 1784.16↤ 16 See Sir Geoffrey Keynes, “George Cumberland and William Blake,” Blake Studies: Essays on His Life and Work (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2nd ed., 1971) 230-52. Blake’s mention of “Your Vision of the Happy Sophis” refers to Cumberland’s novel The Captive of the Castle of Sennaar, printed in 1798.17↤ 17 For historical and bibliographic details, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., ed., The Captive of the Castle of Sennaar (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991). Although Sennaar was suppressed by Cumberland in 1798 and only published in revised form in 1810, Cumberland sent copies of it to some of his friends, and this volume may have been the “kind present” for which Blake had previously neglected to thank Cumberland, an omission for which Blake apologized profusely in his letter to Cumberland dated 2 July 1800 (E 706). The core of the tale concerns Sophis, a utopian society in Africa where property is limited to immediate personal use, energy is considered the divine principle, there is no shame about the naked human body, and gold is despised except for its use in art.18↤ 18 For a number of parallels between Blake’s ideas and those in this novel, see Bentley’s Introduction xxxvi-xli. Blake’s remark that Sennaar has encountered “Envy in Londons accursed walls” may be a way of saying that even Cumberland’s friends had considered the book too daring for publication.

Blake next takes up the proposal for a National Gallery, previously broached by Cumberland in his preface to Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasoni (1793), entitled “A Plan for Improving the Arts in England.” Blake’s letter is an accurate representation of Cumberland’s “Plan.” The latter proposes “that a subscription be commenced . . . for the declared purposes . . . of commencing two galleries, and filling them, as fast as the interest accrues,[e] with plaister casts from antique statues, bas-reliefs, . . . &c. collected not only from begin page 11 | ↑ back to top Italy, but from all parts of Europe.”19↤ 19 Cumberland, Some Anecdotes of the Life of Julio Bonasoni (London: G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1793) 14-15. Blake’s advocacy of Cumberland’s neoclassicism shows his continued high regard—although perhaps prompted more by friendship than by conviction—for that aesthetic. This letter makes clear that Blake’s praise of “the immense flood of Grecian light & glory which is coming on Europe” (letter to Cumberland, 2 July 1800; E 706) continued at least until just before his removal to Felpham. For some reason unknown to us, Blake thought that Cumberland’s plan was close to gaining acceptance in high places at this time. On 2 July 1800, he had even congratulated Cumberland “on your plan for a National Gallery being put into Execution” (E 706). His letter to the editor (John Aikin) of the Monthly Magazine20↤ 20 For Aikin’s editorship from 1796 to c. 1806, see Lucy Aikin, Memoir of John Aikin, M. D. (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1824) 109-44. Lucy Aikin states that “all the original correspondence [to the magazine] came under his [John Aikin’s] inspection; articles were inserted or rejected according to his judgment, and the proof sheets underwent his revision” (110). was part of a campaign that Blake (and presumably Cumberland) thought was close to fruition. The Monthly Magazine may have been chosen because Blake had an entrée there through Joseph Johnson, who has been characterized as the “mentor and assistant” of the Monthly’s publisher, Richard Phillips.21↤ 21 See Gerald P. Tyson, Joseph Johnson: A Liberal Publisher (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1979) 168 and 258n81. Cumberland himself evidently had considerable direct correspondence with the Monthly Magazine, beginning in April 1800, and he published letters to the editor in the April 1800 and March 1803 issues. The first is about sugar substitutes; the second is a defense of Cumberland’s Thoughts on Outline, for which Blake had engraved some of the plates, and which contains a passing reference to Blake. (See G. E. Bentley, Jr., A Bibliography of George Cumberland [New York and London: Garland, 1975] 3n1 and 57). Phillips’s premises at no. 71 St. Paul’s Churchyard were next door to Johnson’s, and Phillips did publish a letter of Blake’s a few years later.22↤ 22 Published in the Monthly Magazine for 1 July 1801 (E 768-69), this letter defends Henry Fuseli against adverse critics. A subsequent letter (14 October 1807, E 769) ) to the Monthly, protesting against the arrest of an astrologer, was not published. However, neither Blake’s letter to the editor nor Cumberland’s proposal ever appeared in the magazine, and while Cumberland may have contributed to an atmosphere that nurtured the idea of a National Gallery, he had no role in the actual founding of the National Gallery, which may be dated from the acquisition of the Angerstein collection for the nation in 1824.

In several letters of 1800 to close friends just before and after his move to Felpham, Blake expressed his ebullient feelings in verse. This newly discovered letter contains the first in this cluster of epistolary poems. It is a brief but important addition to the corpus of Blake’s poetry. In a letter to John Flaxman of 12 September (E 707-08), Blake included a poem in long lines of a type we also find in this poem, a type familiar to readers of Blake’s “Prophetic” works from Tiriel (c. 1789) to Jerusalem (completed c. 1820). The next poem, included in a letter of 14 September from Mrs. Blake to Mrs. Flaxman, is in much shorter lines (E 708-09). The last extant text in this group, sent to Thomas Butts on 2 October, is in short, rhymed couplets (E 712-13). Only the poem addressed to John Flaxman directly invokes the “terrors” and “horrors” (E 707-08) that are so much a part of the poem printed here for the first time. In their prosody and imagery, these seven lines are particularly evocative of the poem Blake was then writing under the title of Vala. The most regular line is the fourth, which comprises a spondee followed by six anapests:

¯ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ |

However, the only other seven-foot line is the first, which has only four anapests among its seven feet:

¯ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ˘ | ˘ ˘ ¯ | ˘ ¯ |

These two lines have much in common with Blake’s septenaries elsewhere, but in this passage as elsewhere Blake is frequently irregular in his long lines. As Alicia Ostriker remarks: ↤ 23 Vision and Verse in William Blake (Madison and Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965) 137.

. . . Blake did not always confine himself to seven-beat lines. Alexandrines play an increasingly important distaff part in his verse, and octometer also becomes frequent. Sometimes there are lines of four or five beats, and sometimes there are lines nine beats long or longer.23Lines 2, 3, 5 and 6 are octometric, while line 7 has nine feet. It is difficult to scan some of these lines because of their irregularity. Ostriker’s observations are again pertinent: ↤ 24 Vision and Verse in William Blake 137-38.

The octometers and other line-lengths give more trouble. They, along with the alexandrines, are of course subject to as many rhythmical peculiarities as Blake imposes on his septenaries. And these odd-size lines appear unpredictably, so that we can never be certain how many beats a line is going to have until we finish reading it.24Line 9, for example, is an anthology of poetic feet, beginning with two iambs followed by a dactyl and a trochee, then a spondee, a trochee, another spondee, an iamb and an anapest. Yet the passage as a whole is dominated by rising feet, anapest and iamb, a rhythmical pattern that matches the rising spirits expressed.

In its development of the theme of freedom from bondage the passage uses a number of images familiar to us from begin page 12 | ↑ back to top other contexts. Key words like manacles, Dungeon, net, Web, Veil, and gore, elsewhere applied to mythical or fictitious figures, are here used to display Blake’s personal situation. The “manacles of Londons Dungeon dark” cannot fail to remind us of the “mind-forg’d manacles” of “London” (8, E 27) of Songs of Experience. “Rending the manacles,” Blake is like Orc in America, whose shoulders “rend the links” that bind his wrists (2: 2, E 52), or the figure in “The Mental Traveller” who “rends up his Manacles” (23, E 484). Blake is also like “the inchained soul” of America, whose “dungeon doors are open” (6: 10, E 53). The “black net” is reminiscent of Urizen’s “dark net of infection” in The [First] Book of Urizen 26: 30 (E 82), closely associated with the “Web dark and cold” that follows Urizen’s footsteps (25: 14, E 82) and that reappears at the end of Night VI of Vala. “Veil,” yoked with the “Web” and “Dropping with human gore,” had not previously had the sense of the obfuscation of vision that it does here and in Vala. “Human gore” had appeared as early as in “An Imitation of Spen[s]er” 32 (E 421) in Poetical Sketches (1783). These nightmarish images of fear and entrapment express the deep depression Blake had fallen into by the end of the 1790s. Counter-balancing them is Blake’s cottage, which “Beams over the Sea, a bright light over France,” behind which are perhaps Jesus’s words from the Sermon on the Mount: “Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid” (Matt. 5.14).

In its short compass the poem moves from the horrific sublime, embodied in the London that Blake was leaving, towards a renewed vision of light. Read with our retrospective knowledge of Blake’s Felpham years and his misery under Hayley’s condescending patronage, the lines strike in us a note of pathos. Blake’s hopes were so high, their realization so unattained. London turned out to be only one objective correlative for Blake’s inner demons and professional distresses. Despite his bold announcements to the contrary, “the Web & the Veil” followed him to Felpham and there took on the psychic and poetic forms populating “The Bard’s Song” in Milton a Poem. In 1803 Blake returned to “Londons Dungeon dark,” soon after rechristened “a City of Assassinations” (letter to Hayley, 28 May 1804; E 751). The letter to Cumberland enriches our sense of Blake’s enthusiasm in the late summer and autumn of 1800, but it also provides a prelude to the disappointment and despair to come.

begin page 13 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]