MINUTE PARTICULARS

The Sound of “Holy Thursday”

William Blake and Joseph Haydn make an odd pair. Quite possibly they passed one another in the street. Great Pulteney Street, where Haydn came to stay with Salomon on 7th January 1791, is only five minutes’ walk from Blake’s house in Poland Street—but the Blakes had almost certainly left for Lambeth not long before. Artistically, their paths are worlds apart. Blake, idiosyncratic and rebellious, inventing his own forms, openly hostile to all things classical; Haydn, content to use the classical forms of his age as the groundwork of his genius. The two men come together, however, over one event, the annual service of the London charity-school children in St. Paul’s, recorded in Blake’s two “Holy Thursday” poems:

Twas on a Holy Thursday their innocent faces cleanAt different times, both witnessed this service. Haydn, in his notebook for 1792, wrote that “no music ever moved me so deeply in my whole life as this, devotional and innocent” (no small thing for Haydn to say). “All the children are newly clad, and enter in procession. The organist first played the melody very nicely and simply, and then they all began to sing at once.”1↤ 1. H.C. Robbins Landon, The Collected Correspondence and London Notebooks of Joseph Haydn (London: Barrie[e] and Rockliff, 1959) 261, where the tune is reproduced as Haydn heard it. Landon carefully heads the page “1791-1792”; New Grove (see next note) dates the event 1791. But though the entries are not in date order, all those around this entry that are dated are from 1792.

The children walking two & two in red & blue & green

Grey headed beadles walkd before with wands as white as snow

Till into the high dome of Pauls they like Thames waters flow

................................

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of heaven among . . . . (Songs of Innocence)

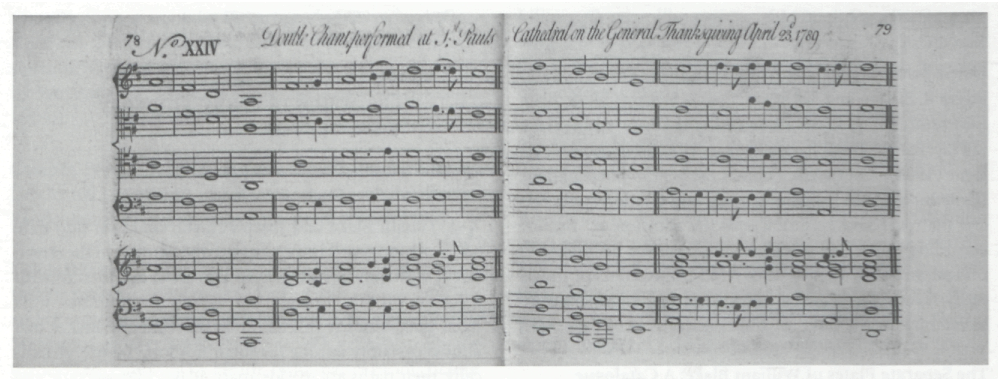

What is more, he wrote down the tune that so moved him. It was composed by John Jones (1728-96), organist at St. Paul’s for many years, and published as no. 24 in his Sixty Chants (1785) (illus. 1).2↤ 2. John Jones, Sixty. I. Chants, Single and Double (London: Longman and Broderip, 1785) 78-79. The copy in the National Library of Scotland (cat. no. Cwn 432) retains “1785” as the title page date, but self-evidently must have been printed no earlier than April 1789. Haydn’s version (of the treble line only) differs slightly from Jones’s, no doubt because the children missed out some of the fine detail of the tune. For John Jones, see The Dictionary of National Biography Volume XXX: 128, and the entry under his name in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., Volume XIII (London: Macmillan, 2001) 194.

begin page 138 | ↑ back to topThis is not a metrical psalm tune. Metrical psalms, though unlike the prose psalms not included in the statutory services of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, enabled the congregation to take an active part in worship, and had become popular in the Church of England in the eighteenth century. This is an Anglican chant, a form (different from plainsong though derived from it) which evolved after the Restoration for the singing of prose psalms and canticles, and so a musical form markedly different from the ballad stanza used for metrical psalms. In his edition, Jones proudly heads this chant with the words “performed at St. Paul’s Cathedral on the General Thanksgiving April 23rd, 1789”—a special service on that St. George’s Day to mark the King’s recovery from his illness. It is a relatively simple tune, but with celebratory harmonies, and unusual, dramatic bare octaves at the opening of each phrase. Haydn did not note the harmonies, though of course he could easily have done so; it appears (from various contemporary references) that the children sang in unison.

But what words were sung to it? Jones gives no indication which psalm he designed this tune for, merely marking, by a capital R (for Rejoicing), the mood of the tune; he leaves the choice of psalm to the choirmaster.

At least one eyewitness account of the King’s thanksgiving service seems to give an answer. Sir Gilbert Elliott reported the event to his wife, saying of the charity children’s singing that he “found it by far the most interesting part of the show”: ↤ 3. Sir Gilbert Elliott, Life and Letters, ed. Nina, Countess of Minto, 3 vols. (London: Longman, Green & Co., 1874) I:304. He was no instinctive philanthropist; for example, he elsewhere treats the antislavery lobby with contempt.

. . . when the King approached the centre all the 6,000 children set up their little voices and sang part of the Hundredth Psalm. This was the moment that I found most affecting; and, without knowing exactly why, I found my eyes running over, and the bone in my throat, which was the case with many other people.3The King himself had asked for “a good old Te Deum and Jubilate”4↤ 4. Lambeth MS letter, 12 April 1789, from the Bishop of Worcester to the Archbishop of Canterbury, quoted in Olwen Hedley, Queen Charlotte (London: John Murray, 1975) 174. —the latter being the traditional name for the 100th Psalm. We might suppose, then, that at this service Jones’s Double 24th was the tune used for the prose 100th Psalm, “O be joyful in the Lord, O ye lands,”5↤ 5. The text of the psalms in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer in general follows the 1537 Great Bible, rather than the 1611 Authorized King James version, “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord.” and also that the charity children were gathered to sing it on this special occasion (quite distinct from their own annual service, which was not due for another month).

But this does not settle the question. There are two ways in which the 100th Psalm might have been sung: as a chanted prose psalm, or in the popular metrical version by William Kethe (d. 1594), to its contemporary tune, the “Old Hundredth.” Both sets of psalms were commonly included in editions of the Book of Common Prayer at this period. It is true that Haydn’s note (and perhaps Blake’s poem) suggests that the service opened with the children singing a chant, and the 100th Psalm would have been appropriate. But two documents6↤ 6. “Psalms and Anthems to be sung at the Anniversary Meeting” (1797) is a single-sided handbill resembling, and catalogued as, a broadside. The second document is: John Page, “The / ANTHEMS & PSALMS / as Performed at / ST. PAUL’S CATHEDRAL / On the day of the Anniversary Meeting of the / Charity Children . . . 3/-” (London: Ann Rivington). The Library dates it 1800. Page, “Conductor of the Music,” has arranged the music in two staves for keyboard, and marks in detail where the children are to sing. I am indebted to Mr. J.J. Wisdom, Librarian of St. Paul’s, for finding these documents for me in the Guildhall Library. in the Guildhall Library in London tell a more complex story.

begin page 139 | ↑ back to topOne, dated 1797, is a handbill, “Psalms and Anthems to be sung at the Anniversary Meeting,” consisting of the order of service. This begins: “Before Prayers the 100th Psalm”; the text of Kethe’s metrical psalm, “All people that on earth do dwell,” follows. Next: “The Reading Psalms to be Chaunted by the Gentlemen of the CHOIR,—the Children to join in the Gloria Patri to each Psalm.” At this point the second document, “The ANTHEMS & PSALMS . . . ,” a collection of the music of the service, annotates “Double Chant,” and prints Jones’s 24th.

The children also took part in three anthems. In the first, “the Coronation Anthem” (Handel’s “Zadok the Priest”), the children were to join in the dramatic repeated phrase, “God Save the King! Long live the King! May the king live for ever!” at the climax of the piece, and “Hallelujah! Amen” at the end. The second was a short 16-bar chorus to the word “Hallelujah!,” which the children sang throughout, the girls alone being marked to sing four bars in the middle. The last was Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus,” in which, again, “the Children [are] to join in such Parts as are marked”— in this case, substantial passages at the beginning and the end, more than a third (the easiest third) of the whole.

As to the opening psalm: on these occasions, then, it was not Jones’s prose chant, but the metrical version, the Old Hundredth. This service found places for two more metrical psalms: Nahum Tate’s 113th before the sermon, and four verses of Kethe’s 104th (to William Croft’s tune, “Hanover”) after it. The prose “reading psalms,” on the other hand, were part of the formal body of the service, and, depending on circumstances, in parish church or cathedral, might be literally read by the minister, or chanted, either by him or by the choir (if any). Here the cathedral choir alone chanted the “reading” psalms to Jones’s 24th, the children joining in only at the end.

What was the most moving point of the service for Blake and Haydn? Elliott is quite plain; for him, it was the children’s singing of the Old Hundredth, the dramatic beginning of the special thanksgiving service. The Innocence poem suggests that Blake felt the same effect at the charity service. But it was Jones’s chant tune later in the service that Haydn wrote down. Perhaps he was moved most powerfully at the point of a second raising “to heaven the voice of song,” “devotional and innocent,” when the thousands of children broke into “Glory be . . .” to Jones’s tune, after the more attenuated monotone chanting of the text of the psalm. This could well have led Haydn to note down the tune they sang.

Dr. William Vincent, trying by his little book7↤ 7. Rev. William Vincent, D.D., Considerations on Parochial Music, 2nd ed. with additions (London: Cadell, 1790) 10n. He was Head-master of Westminster School from 1788, and Dean of the Abbey from 1802. to improve congregational singing in parish services, certainly found the chant inspiring. Almost in a parenthesis—in a footnote, that is, he says that, for untrained singers, “. . . no chant is better calculated than that which the charity children sing at the conclusion of each psalm at St. Paul’s.—It is composed by Mr. Jones . . . .” Vincent makes other enlightening comments about the quality of the singing at the annual charity-school service. The singing of the Anglican chant requires a certain skill; there is no rhythmical pattern to follow, as in an ordinary song, and untrained singers can easily fall into a gabble. Vincent laments the general standard of singing in the chapels of several hospitals and public charities in the metropolis, where “they universally sing at the utmost height of their voices, and fifty or an hundred trebles strained to their highest pitch, united to the roar of the full organ, can never raise admiration of the performers . . .” (p. 8). Instead of that coarseness—perhaps because the children of Coram’s Foundling Hospital (which “appears to have obtained all that is desirable in this point”8↤ 8. Vincent, 11n. Charles Dickens alludes to the continued quality of the musical training at Coram’s Hospital in Little Dorrit (1855-57), ch. 2. ) formed a tenth of the whole, and because there were public rehearsals— “the effect is just the reverse in the general assembly of the charity children at St. Paul’s . . . . The union of five thousand trebles, raises admiration and astonishment . . .” (p. 9).

We should not really ask, “What point was most moving?,” since it would be a total effect that people would take away with them. It is plain from all allusions to this service that the similar emotional response of such very dissimilar people as Blake, Haydn, and Elliott was widespread. In 1800, John Page, the choirmaster, claimed for this service, in eighteenth-century style, that

amongst the many laudable Charities with which this Munificent Kingdom abounds, there is none . . . can fill the mind with such affectionate sensation and religious awe . . . . [T]hat public display of Benevolence, has been eagerly attended by crowded Congregations annually, for nearly a Century past . . . .The self-congratulatory tone grates today, but it does seem that the feeling at that time for the charity-children’s service was not unlike the modern popular affection for the annual carol service at King’s College, Cambridge.

What song the sirens sang may be beyond conjecture; but we know what the “Holy Thursday” children sang. And begin page 140 | ↑ back to top though we cannot be certain at what point in the service Blake’s and Haydn’s eyes began to fill, we know what sound it was that could so raise Blake’s emotions: whether immediately and simply, as in Innocence; or, as in Experience years later, to make him challenge us to be satisfied with a lump in the throat when the children sing:

Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor?

It is a land of poverty! (Songs of Experience)