article

Blake, Bacon and “The Devils Arse”

Blake owned a copy of Francis Bacon’s Essays Moral, Economical, and Political (London: J. Edwards and T. Payne, 1798), which he annotated extensively. The book was first described by Alexander Gilchrist, who writes that “the artist’s copy of the Essays . . . is roughly annotated in pencil, in a very characteristic, if very unreasonable, fashion.”1↤ 1. Gilchrist 1:315. The annotations were made in various pencils. The thickness of the line and the pressure applied to the paper vary considerably, which may indicate that the comments were not all made at one time. This copy, which is bound in green cloth with a few of the first pages loose, is now held at Cambridge University Library.2↤ 2. The book has shelfmark: Keynes U.4.20.

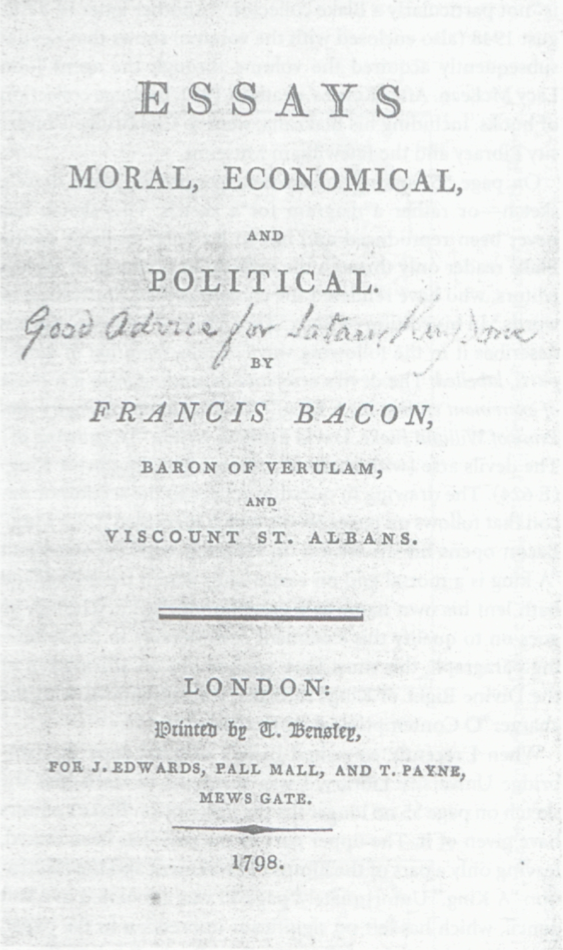

On the title page Blake writes: “Good Advice for Satan’s Kingdom” (E 620) (illus. 1).3↤ 3. Unless otherwise indicated, all citations from Blake are from Complete Poetry and Prose, ed. Erdman, and will be marked as E in the text. G. E. Bentley, Jr., notes that the frequent comparison of Bacon’s advice to that of Christ suggests a date for the annotations not long after this edition was published (BB 682). This was not the first time Blake attacked Bacon in a series of annotations. We know that Blake also owned and annotated a copy of Bacon’s The Tvvo Bookes of Francis Bacon (London, 1605), for he writes in his annotations to The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1798): “when very Young . . . I read . . . Bacon’s Advance of Learning on Every one of these Books I wrote my Opinions” (E 660), and, in a letter of 23 August 1799, he quotes Bacon’s “Advancemt of Learning, Part 2, P 47 of the first Edition” (E 702-03). Blake’s copy of this book has never been traced.

In 1833 Samuel Palmer acquired Blake’s annotated copy of Bacon’s Essays and inscribed this year and his name on the first endpaper. (Several of Blake’s books came into Palmer’s possession after Catherine Blake’s death.) Blake’s editor, Sir Geoffrey Keynes, who later acquired the book, surmised that it was passed on to Samuel Palmer’s son, A. H. Palmer, who probably kept it until his death.4↤ 4. Keynes (1957) 152. Also reprinted in Keynes (1971) 90-97. Keynes was told by A. G. B. Russell that it was then held by “Mr. Lionel Isaacs of the Haymarket about 1900.”5↤ 5. Keynes (1921) 51. In his autobiography, The Gates of Memory, Keynes describes how in 1947 he approached the Boston bookseller George T. Goodspeed and asked if he had sold any books relating to Blake. Goodspeed could recall that eighteen years previously, in 1929, he had sold a book containing some annotations of Blake’s to the pharmaceutical millionaire of Indianapolis, Joshua K. Lilly, Jr., the founder of the Lilly Library6↤ 6. Keynes (1981) 301-02.

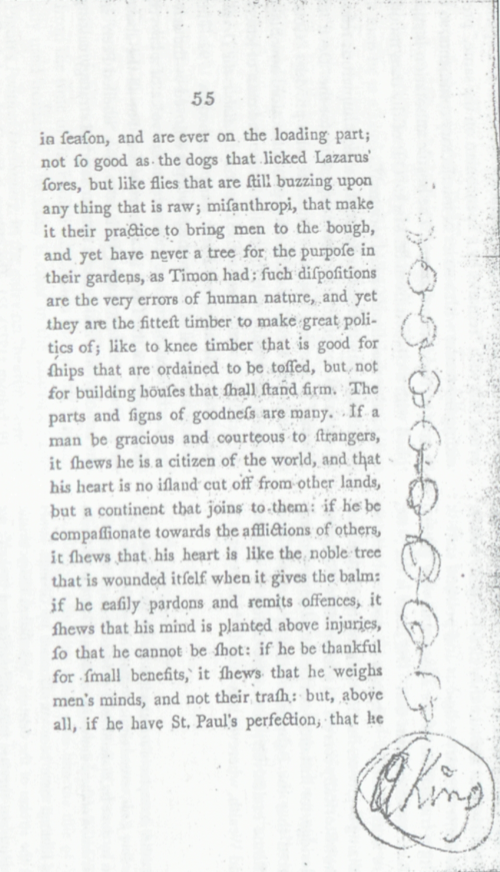

On page 55, among the written marginalia, Blake drew a sketch—or rather a diagram for a sketch. This sketch has never been reproduced and has so far been available to the Blake reader only through the eyewitness accounts of Blake’s editors, who have rendered the contents of the illustration in words.8↤ 8. Unfortunately, no holograph facsimile is available of these annotations as there is of Blake’s marginalia to Bishop Richard Watson; see Annotations, ed. James. In his edition of Blake: The Complete Writings, Keynes describes it in the following way: “A representation of hinder parts, labelled: The devil’s arse, and depending from it a chain of excrement ending in: A King.”9↤ 9. Complete Writings, ed. Keynes (1979) 400. In The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, David Erdman writes: “[A drawing of] The devils arse [with chain of excrement ending in] A King” (E 624). The drawing in question relates to the section of Bacon that follows on pages 56-60, which is entitled “Of a King.” Bacon opens his discussion on kingship with the statement “A king is a mortal god on earth, unto whom the living God hath lent his own name as a great honour” (56). Though he goes on to qualify this statement considerably in the following paragraph, this must have seemed like an affirmation of the Divine Right of Kings to Blake, who responded with the charge: “O Contemptible & Abject Slave” (E 626).

When I recently consulted Blake’s original copy in Cambridge University Library, I was surprised to learn that the sketch on page 55 no longer fits the description Blake’s editors have given of it. The upper part of the page has been erased, leaving only a part of the lumps of excrement and the inscription “A King.” Unfortunately, page 55 was annotated in a soft pencil, which has left no significant impression in the paper. With the help of the staff in the Rare Books Reading Room, I have thoroughly examined the page: even with the help of UV light, the erased impression cannot be lifted.10↤ 10. I owe thanks to library officer (Dept. of Rare Books) Annemarie Robinson for her help and assistance with examining the volume. In the top margin of the page, only a faint “T” and some of a “D” can with the utmost difficulty be made out when the page is viewed in the right light and at the right angle: this does not show on a microfilm copy (illus. 2). What is striking is that Erdman, whose mark of distinction is an otherwise rigorous particularity in recording practically every deletion or insertion in Blake’s annotations or manuscripts, apparently finds no reason to make any note of the fact that a considerable part of the drawing is not visible. Only G. E. Bentley, Jr., in his 1978 edition of William Blake’s Writings rates this important enough to mention it upfront, informing us that page 55 is “[An erased sketch of buttocks (?), with an erased identification:] The Devils arse[(?). From these depend a chain, at the bottom of which is:] A King.”11↤ 11. Writings, ed. Bentley (1978) 1:1430. In Keynes’ edition of Blake’s Complete Writings, a note on the vandalized state of the drawing is found in the appendix of editorial comments. Keynes attaches relatively little importance to the erasure, for as he confidently notes, “the upper part of the diagram has been rubbed out, but the impress of the pencillings is clearly visible.”12↤ 12. Complete Writings, ed. Keynes (1979) 905. This is similar to the description he gave it when first publicizing his acquisition of the volume in the TLS on 8 March 1957. Keynes here singles out the sketch for particular attention, making Palmer responsible for “partially, though ineffectually, erasing the drawing.”13↤ 13. Keynes (1957) 152. Apparently, at the time Keynes bought the book, the upper part of the drawing stood out with unequivocal clearness; examining it today yields no such positive result.

After correspondence with Professor Bentley, I learned that when Keynes put Bacon’s Essays on deposit for him in 1964, the image was so faint that he could make nothing of it. Yet, in all revisions of Blake: The Complete Writings (1957, 1969, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1979), i.e. after Bentley examined the drawing and found the upper part had vanished beyond legibility, Keynes makes no comment on any changes in the imprint on this page. How the upper part of the drawing could have faded from Keynes’ confident “clearly visible” of 1957 to a state of invisibility when Bentley examined it in 1964 still demands explanation. The condition of the book today does not appear to vary from the description given of it by Keynes in 1957. That the page should have been exposed to sunlight or other such external factors that might have caused its deterioration seems unlikely, as the bottom part of the drawing stands out as clearly as many other annotations in the volume. Furthermore, it is an axiom in holograph forensics that whereas some inks may fade, this is not normally the case with pencil.

Fortunately, we are not completely without a visual record of what the original and complete drawing looked like. Quite unexpectedly, another copy of Bacon’s Essays turned up during my research in the library. This was an identical edition, which Keynes had purchased and into which he, with rigorous precision, copied out Blake’s annotations page for page in the exact place they appeared in the original.14↤ 14. Keynes’ copy has shelfmark: Keynes E.2.2.24. This hitherto unrecorded copy, transcribed in what now appears as a reddish-brown ink, was probably made in 1949, the year Keynes writes on the front paste-down endpaper. This indicates that this transcript copy was written up shortly after Keynes acquired the book, perhaps for his own easy reference or in preparation for editing the annotations. On page 55 the drawing is shown as it appeared before the obliteration. A comparison begin page 139 | ↑ back to top

Despite the mystery of the erasure, there is no reason to believe that Keynes “invented” this reading. Though he at times made mistakes in deciphering Blake’s hand (as later editors have pointed out), there are no records of Keynes ever making things up, and his integrity as a scholar speaks against any such suggestion.

Keynes’ conjecture that the erasure was the work of Samuel Palmer is plausible.15↤ 15. There are other examples of erasures in Blake’s work. For example, in the ms. to The Four Zoas, several erotic portions are partly obliterated. Whether this was by done by Blake himself or by others later is unclear. For a detailed discussion of these drawings, see Grant 192-94 and Lincoln 58. It may be significant that it is only the part that refers to the satanic that he sought to remove. A similar attempt can be found in Blake’s annotations to Bishop Watson’s An Apology for the Bible (1797). This book was also acquired by Palmer, who inscribed his name on the title page. On the verso of the title page, Blake prefaced the annotations with the statement: “The Beast & the Whore rule without control” (E 611). Erdman comments that the sentence is cancelled by “a ruled double line, in pencil” and judges this to be “uncharacteristic of Blake” (E 884-85).16↤ 16. Erdman’s findings have been corroborated by G. Ingli James on grounds that the strokes of the deletion “lack Blake’s characteristic strength and decisiveness: they are faint, undulating and broken”; see “Notes to Transcript,” in Annotations, ed. James, n2.

It is possible that Palmer misconstrued the statement as literal and affirmative, where we may assume Blake wrote allegorically and critically. Varying with the time, place and persuasion of the interpreter, the figures of the “Beast” and the “Whore” from the Book of Revelation have been called in to identify the Jews, the Ottomans, France, Charles I, Cromwell, the aristocracy, capitalism, the American slaveholders or whatever forces in society the interpreter wanted to oppose. There is a long tradition in Protestant propaganda of allegorizing the Pope and Catholicism by these New Testament figures for the Antichrist, but in Blake they clearly signify a more immediate and contemporary religious and political state of affairs. Offering a translation of the allegory in very general terms, Jacob Bronowski explains that “The Beast is the State, and the Whore is its Church.”17↤ 17. Bronowski 82. Though he does not rely on any contextualizing evidence, Bronowski’s interpretation may however still be historically correct, In a footnote to “Religious Musings,” Coleridge, for instance, can be found commenting: “I am convinced that the Babylon of the Apocalypse does not apply to Rome exclusively; but to the union of Religion with Power and Wealth, wherever it is found.”18↤ 18. Complete Poetical Works, ed. E. H. Coleridge 1:121n1. However, it is possible that Blake’s reference may more specifically refer to Prime Minister Pitt and Queen Charlotte. In Prophet Against Empire, Erdman draws attention to the fact that the Queen’s influence increased as a consequence of George III’s madness in 1788. She was believed to rule the Empire through Pitt. The Prime Minister’s peace in 1790 had popularly been attributed to the Queen’s influence. On this theme Gillray drew a caricature allegorizing Milton’s Sin and Death as the Queen and Pitt.19↤ 19. Erdman (1977) 221. The cartoon is Sin, Death, and the Devil (1792); see George no. 8105. Whatever reference Blake may have meant to give this allegory, it seems unavoidably political; the phrase serves as a prefatory maxim summing up Blake’s defense of Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason. If the deletion was made by Palmer out of his inability to decode Blake’s political allegory (misreading it as a religious heresy that he saw fit to remove), it is likely that the same could have been the case with “The Devils Arse.”

When Gilchrist compared Blake’s annotations to Bacon with those to Reynolds, he finds them lacking the “leaven of real sense and acumen which tempers the violence of those on Reynolds” and only quotes out of the “interests of faithful biography.”20↤ 20. Gilchrist 1:315. The annotations are admittedly written in the mode of literary satire rather than as a considered philosophical argument.

Many of Blake’s annotations are really clearly spontaneous. He employs shock tactics and satire as an immediate response rather than attempting to establish a coherent counter-argument. The form of hostile dialogue we find in the annotations to Bacon and other of Blake’s “Spiritual Enemies” whose books Blake owned can also be seen in published satire. In Pig’s Meat, Thomas Spence prints Sir John Sinclair’s An Antidote Against Revolutions, a piece of loyalist propaganda showing the anarchy that will erupt if monarchy is overturned. Spence prints this with “remarks by a Spenconian on the same,” providing the reader with a series of interjectory comments, so it is now turned into a dialogue. The hostile annotation is supplied with a citation from St. Mark: “Out of thy own mouth will I judge thee thou wicked servant.”21↤ 21. Pig’s Meat 3 (1796): 186-92.

In Blake’s annotations to Bacon, he makes numerous references to his opponent as someone speaking for the “Devil” or “Satan.” In positing Bacon as someone who provides “Good Advice for the Devil” (E 625), it has gone unnoticed how Blake shares a vocabulary with the biblical critic and man of letters, Alexander Geddes, whose satire L’Avocat du diable: the Devil’s Advocate; or, Satan versus Pictor was published in 1792. This work is a political satire on the privileges enjoyed by the aristocracy in legal matters; it is written in the voice of a lawyer, who represents the Devil in a court of law. For all the abuse he has been made to suffer he is seen as a “libelled Peer.” In the annotations, Blake uses a similar satirical strategy, casting begin page 141 | ↑ back to top

Bacon in the role of the Devil’s advocate, understanding “the kingdom of Satan” in political terms. For instance, on page 14 Blake writes: “The Prince of darkness is a Gentleman & not a man he is a Lord Chancellor” (E 622). Blake seems also to address the political implications of Bacon’s thinking when, in his annotations to The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, he writes that “Bacons Philosophy has Ruind England” (E 645). Understanding the sketch within its context of political satire is important as it relates to a topos of revolutionary satire in the 1790s. It is to this context I shall now turn.Blake’s satirical drawing is clearly motivated by Bacon’s claim that a king is divinely ordained. The king has therefore traditionally been given the title “heaven-born.” According to the OED, this term had in analogy also been used to describe governors of the state, who were seen as endowed with divine skill and abilities of governance. But, as the OED also records, from the time of the French Revolution the epithet is generally used ironically. The irony is clear in the satirist Charles Pigott’s Political Dictionary. In the entry on “heaven-born” we are laconically informed that it means “the most infamous of mankind” (55). It is similarly wholly ironic when Pigott refers to “Mr. Pitt, and his heaven-born family, Mr Rose, Henry Dundas, and others” (104). The term is also played upon in the cartoonist Richard Newton’s political drawing The General Sentiment (1797).22↤ 22. George no. 8999. Here Pitt is depicted in the gallows, hanging by the neck, beneath which two characters of obvious plebeian origin make the ironic wish: “May our heaven born minister be SUPPORTED from ABOVE.”23↤ 23. Though Pitt was the favorite victim of this irony, at times Edmund Burke was satirized in similar terms. In a piece that appeared in The Courier, 28 November 1794, Burke is represented as a “puppet-master,” who controls a parliament reduced to “AUTOMATA, OR MOVING PUPPETS,” a function which gives him the title of “HEAVEN-BORN CONIURER.” For the origin of the term, see Barrell 11.

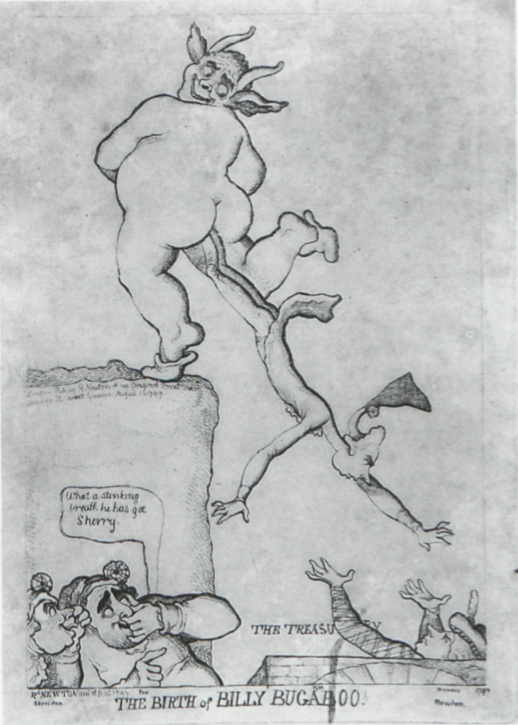

The disruption of the semantic content of the phrase could also manifest itself as a satirical inversion. In a placard dated “Norwich, 16 October 1795, a call to form popular Societies and demand redress of grievances,” Pitt is also satirized. The text here concludes, “You may as well look for chastity and mercy in the Empress of Russia, honour and consistency from the King of Prussia, wisdom and plain dealing from the Emperor of Germany, as a single speck of virtue from our Hellborn Minister.”24↤ 24. Cited in Rose 284. This inflammatory piece of satire, inverting “heaven-born” to its infernal opposite, was widely circulated and attained great popularity. It inspired Richard Newton to a couple of satirical prints, in which he renders the inversion of the phrase in pictorial puns. In The Devils Darling (1797), the Devil is dandling Prime Minster Pitt (one of Newton’s favorite victims) on his knee. Underneath the design is written, “Never a man beloved worse / For sure the Devil was his nurse.”25↤ 25. George no. 9011. This print is reproduced in Alexander 49. In The Birth of Billy Bugaboo (1797), Pitt’s policies of taxation are criticized. The Devil is shown standing on the edge of a cliff “giving birth” to Pitt by excreting him out of his backside into the arms of Henry Dundas, who pokes his head out of a building inscribed “The Treasury.” Beneath the cliff are also Fox and Sheridan holding their noses to the smell. Fox remarks to Sheridan, “What a stinking breath he has got Sherry” (see illus. 4).26↤ 26. George no. 9029. Some years ago Marcus Wood brought this cartoon to our attention in a “Minute Particular,” suggesting that it supplied the major compositional elements for Blake’s engraving The Dog, which was engraved for William Hayley’s Ballads (1805).27↤ 27. See Wood. The image is featured on the front cover of that issue of Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly. According to Wood, Blake apparently liked the visual composition enough to borrow the material of a satirical sketch and use it in a non-satirical context. If Blake annotated his copy of Bacon’s Essays shortly after the volume was published in 1797, Newton’s cartoon of the same year would still have been fresh in his mind.

There is a long tradition of scatological reference in caricature. Heaping abuse and libel on authorities by such begin page 142 | ↑ back to top

uncouth imagery dates back to the Reformation polemic and the Lutheran supporters’ use of the so-called Schandbilder.28↤ 28. See Scribner, esp. 84-87; also Hyman. The association of defecation and demons is, for example, used to great effect in a flyleaf showing The Origins of Monks (Von der München Ursprungen, 1523), where we see the Devil relieving himself by excreting a pile of monks (illus. 5). In the 1790s scatological reference became a stock weapon in the rhetoric of the Revolution. In his discussion of James Gillray’s and Jacques-Louis David’s anti-aristocratic illustrations, the art historian Albert Boime shows how the excremental was habitually associated with the ancien régime. This was a way of breaking “a privileged code of politesse and decorum,” establishing a “discourse for the crowd . . . encoding a new environment with an inclusive, nonprivileged space.”29↤ 29. Boime 75. An example of this in French caricature is the anonymous print The Two Infuriated Devils (Les deux Diables en fureur, 1790), which shows the two notorious clergymen Abbé Maury and Jean-Jacques d’Eprémesnil excreted from the bottoms of two red-winged devils. The lines underneath the illustration translate: “On 13 April 1790 two flying devils / Made a bet/ Who would shit most foul / On human nature / One shat the Abbé M. . .y / The other paled / And dropped D’E. . .y/And his entire clique” (illus. 6).30↤ 30. The ministers Maury and d’Epremesnil were two of the most outspoken critics of the National Assembly’s hostility against maintaining Catholicism as a state religion, as this would put an end to the privileges formerly enjoyed by the clergy. The design is reprinted in French Caricature (1988). Newton would have been familiar with such revolutionary propaganda through his employer, the radical print publisher William Holland, who made French prints available to the English public, a trade that also went the other way.31↤ 31. In the early 1790s, Holland advertised on his prints that “In Holland’s Caricature Exhibition Rooms may be seen the largest Collection in Europe of Political and other Humorous prints with those published in Paris on the French Revolution.” For Holland’s business and his affiliation with Newton, Gillray, Cruikshank and others, see Alexander 26.It is worth noting that the connection between political libel and the demonic was current in the 1790s. We find, for instance, the people’s prophet Richard Brothers addressing begin page 143 | ↑ back to top

his reader as an oppressed subject of George III: “thou didst . . . submit thyself to the laws that were imposed on thee by a monster spewed out of HELL.”32↤ 32. “Letter received from Richard Brothers,” printed in Wright 29. On Brothers’ prophetic politics, see Garrett 177-220. In the political debates of the 1790s, the exposition of the origin of tyranny and oppressive institutions was a key line of attack used by the opposition, perhaps most notably in the writings of Thomas Paine. This was also worked into satire, as for instance in Eaton’s Politics for the People and its investigation into “The Origins of Nobility.”33↤ 33. Politics for the People 3 (1793): 26-31. The same publication later featured “The Genealogy of a modern Aristocrate,” which is a list of how one evil has begot another, starting at the time when “The Devil begat Sin” and ending with how “Time-Serving Sycophants begat Modern Aristocracy on the Body of the Whore of Babylon.”34↤ 34. Politics for the People 7 (1794): 6.The image of “hell-born” would have come naturally to Blake, as Bacon, on page 56, after his statement that “God hath lent his own name as a great honour” to kings on earth, qualifies this by stating that a king should not be so “proud” as to think himself immortal as a god and “flatter himself that God hath with his name imparted unto him his nature also.” This apparently spurred Blake on to show that a king’s office is not imparted from Heaven but from Hell: the king being born out of the “Devils Arse.” It is Blake’s visual rendering of this satirical attack that has now sadly been partially lost.

Works Cited

Alexander, David. Richard Newton and English Caricature in the 1790s. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester in association with Manchester UP, 1998.

Bacon, Francis. Essays Moral, Economical, and Political. London: J. Edwards and T. Payne, 1798.

Barrell, John, ed. “Exhibition Extraordinary!!”: Radical Broadsides of the Mid 1790s. Nottingham: Trent Editions, 2001.

Bentley, G. E., Jr., ed. William Blake’s Writings. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1978.

Blake, William. Annotations to Richard Watson—An Apology for the Bible in a Series of Letters Addressed to Thomas Paine. 8th ed., 1797. Ed. G. Ingli James. Cardiff: University College Cardiff P, 1984.

Boime, Albert. “Jacques-Louis David, Scatological Discourse in the French Revolution, and the Art of Caricature.” French Caricature and the French Revolution, 1789-1799. Los Angeles: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles; Chicago: Distributed by the U of Chicago P, 1988. 67-82.

Bronowski, Jacob. William Blake and the Age of Revolution. New York: Harper Colophon, 1969.

Coleridge, Ernest Hartley, ed. The Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1912.

Erdman, David V. Prophet Against Empire: A Poet’s Interpretation of the History of His Own Times. Rev ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1977.

Erdman, David V., ed. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Rev. ed. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

French Caricature and the French Revolution, 1789-1799. Los Angeles: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles; Chicago: Distributed by the U of Chicago P, 1988.

Garrett, Clarke. Respectable Folly: Millenarians & the French Revolution in France & England. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins UP, 1975.

George, Mary Dorothy, ed. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum (1771-1832). 7 vols. London: British Museum, 1935-54.

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake. Rev. ed. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1880.

Grant, John E. “Visions in Vala: A Consideration of Some Pictures in the Manuscript.” Blake’s Sublime Allegory. Ed. Stuart Curran and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. Madison: University of Wisconsin P, 1973. 141-202.

Hyman, Timothy. “A Carnival Sense of the World.” Carnivalesque. Ed. T. Hyman and R. Malbert. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2000. 8-73.

begin page 144 | ↑ back to topKeynes, Geoffrey. A Bibliography of William Blake. New York: Grolier Club, 1921.

Keynes. “William Blake and Sir Francis Bacon.” TLS 2871 (8 March 1957): 152.

Keynes. Blake Studies: Essays on His Life and Work. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1971.

Keynes, ed. Blake: The Complete Writings with Variant Readings. Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1979.

Keynes. The Gates of Memory. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1981.

Lincoln, Andrew. Spiritual History: A Reading of William Blake’s Vala or The Four Zoas. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1995.

Pigott, Charles. A Political Dictionary Explaining the True Meaning of Words. London: Daniel Isaac Eaton, 1795.

Pig’s Meat; or Lesson for the Swinish Multitude. London: T. Spence, 1793-96.

Politics for the People; or, a Salmagundy for Swine. London: D. Eaton, 1793-95.

Rose, J. Holland. William Pitt and the Great War. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1911.

Scribner, R. W. For the Sake of Simple Folk: Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1994.

Wood, Marcus. “A Caricature Source for One of Blake’s Illustrations to Hayley’s Ballads.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 24.1 (summer 1990): 247-48 [31-32].

Wright, John. A Revealed Knowledge of Some Things That Will Speedily be Fulfilled in the World. London: n.p., 1794.

![Jo[annes] vid[e].

Vos ex patre diabolo

estis: et desideria patris

vestri perficietis.

Non vocabitur in eternu[m]

seme[n] pessimoru[m]. Esa[ias] vid[e].](img/illustrations/Ursprungen.37.4.bqscan.png)