ARTICLE

Blake’s “Annus Mirabilis”: The Productions of 1795

Author’s note: An online version of this article, with six more illustrations, all illustrations in color, and a slightly longer first section, is available on the journal’s web site.[e] Illustrations that appear only online are indicated in the print version by the online illustration number preceded by an “e” (e.g., illus. e4).

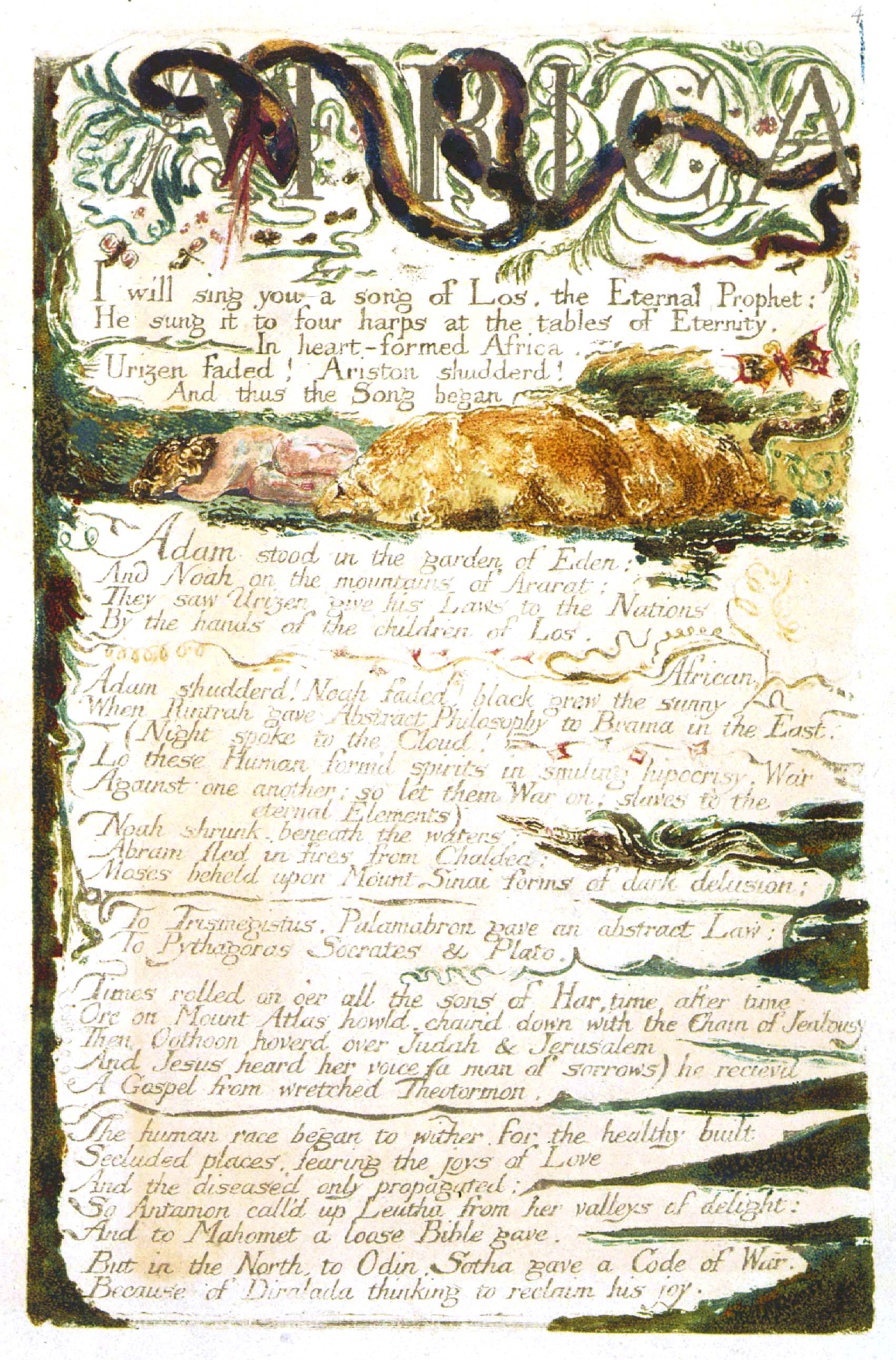

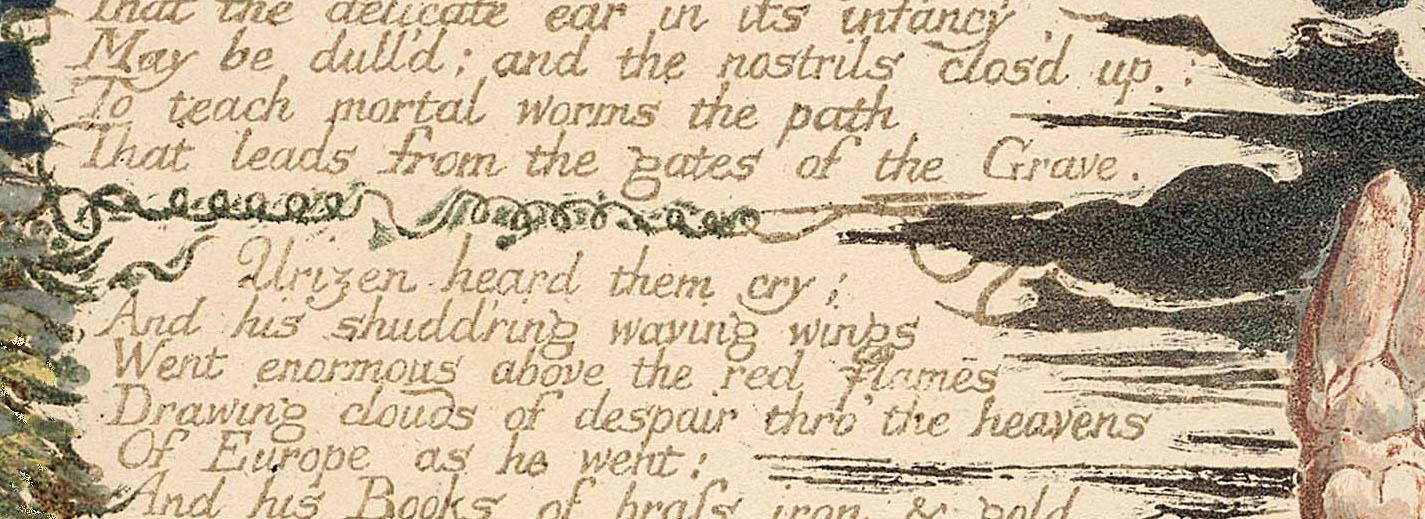

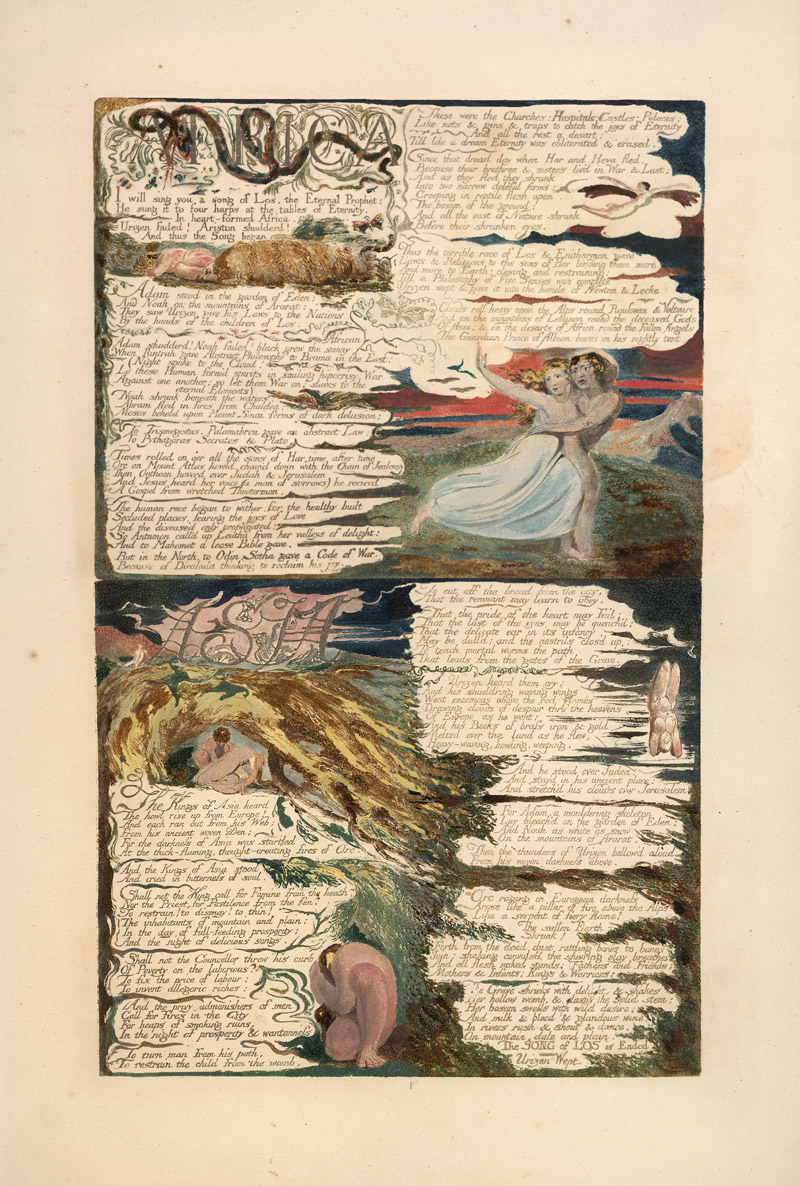

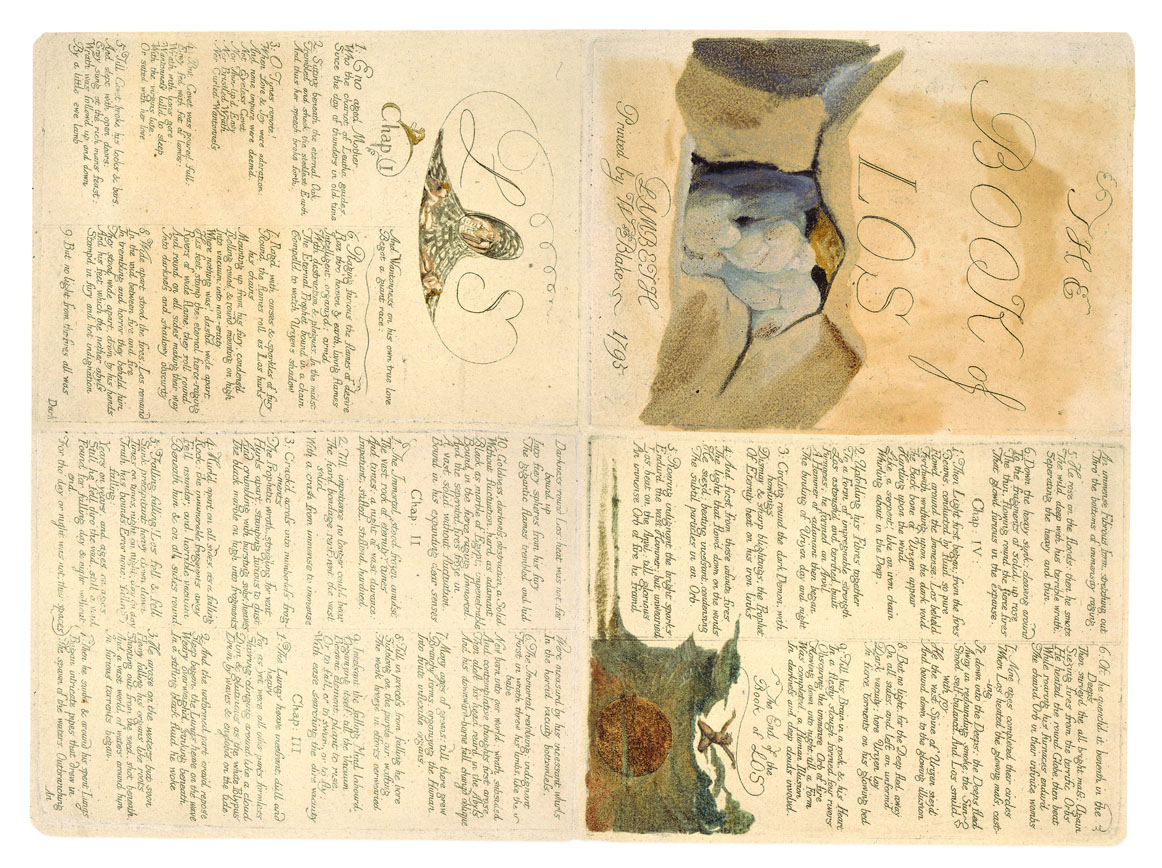

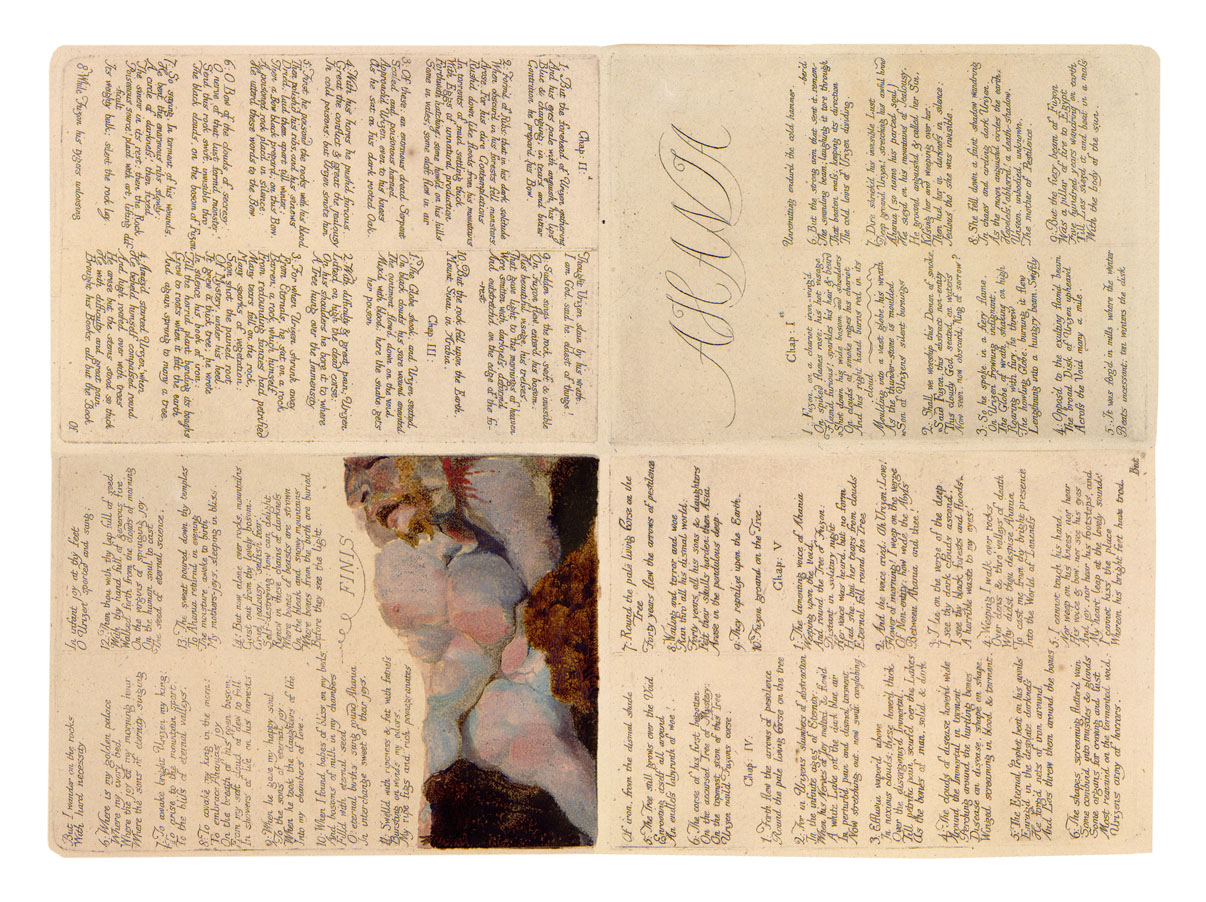

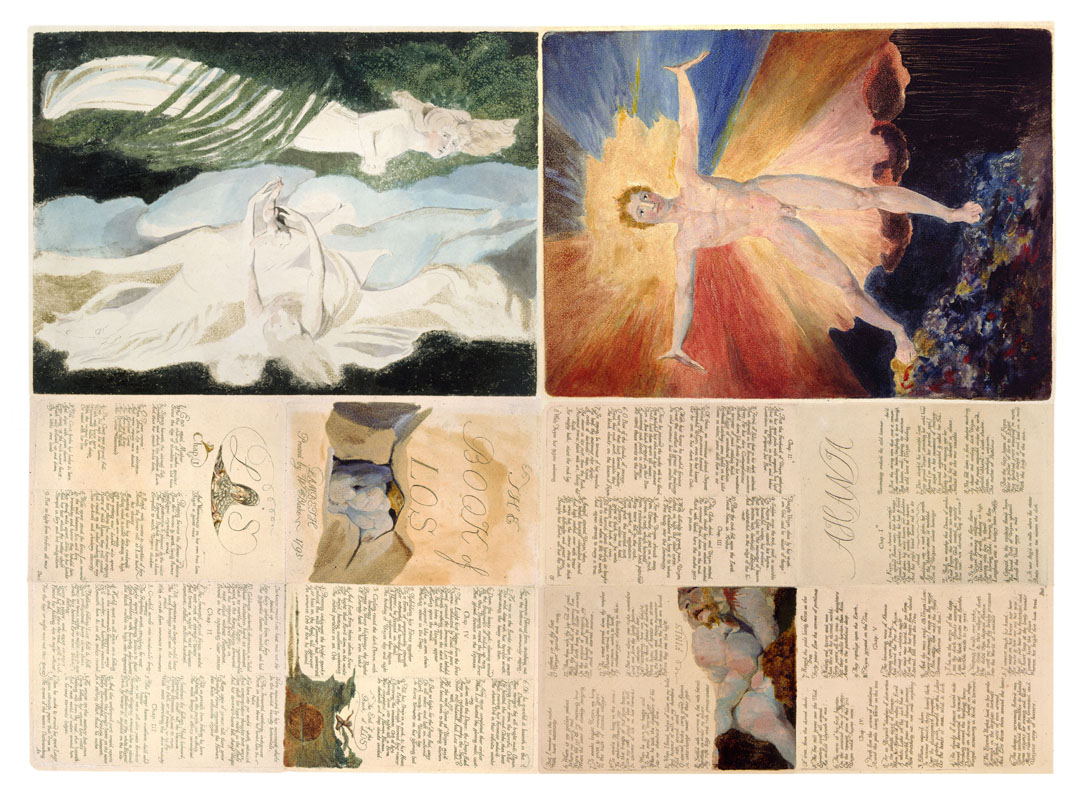

IN 1795, Blake produces The Song of Los, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los, executes 12 large color-printed drawings, color prints a few etchings, reprints 8 copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, reprints most of his illuminated canon to date in a deluxe, large-paper set, and begins the 537 watercolor drawings of Night Thoughts.*↤ *I would like to thank Robert Essick for reading an early draft of this essay and Todd Stabley, multimedia consultant, formerly of the Center for Instructional Technology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for his assistance in digitally recreating Blake’s copper sheets and virtual designs. The first period of illuminated book production, 1789-95, culminates, new experiments in combining printmaking and painting are begun and perfected, and work as designer and painter begins to dominate Blake’s energies and time for the next 10 years. In this essay, the second of a two-part study, I focus on the last of Blake’s illuminated books from this period, The Song of Los, The Book of Los, and The Book of Ahania, trying to sequence them from a purely materialist perspective—by recreating the large copper sheets from which the individual plates were cut—to see how Blake’s creative process, including changes of mind and false starts, unfolded through production and how these particular works and their techniques might relate to one another, to the color-printed drawings, and to the experiments in color printing that lie behind them both.1↤ 1. Part 1, “Blake’s Virtual Designs and Reconstruction of The Song of Los,” uses digital imaging to recreate Blake’s original designs for the text plates of The Song of Los and to realize the virtual designs in this and a few other illuminated books. Blake’s virtual designs are designs we create mentally by recombining an illuminated book’s related images.

The Song of Los is generally thought to precede the two other books, which is to say, Blake is thought to have returned to America a Prophecy (1793) and Europe a Prophecy (1794) with “Africa” and “Asia,” the two parts of The Song of Los, rather than continuing The First Book of Urizen (1794), because he began the “continental” books before the “Urizen” books.2↤ 2. Europe and Urizen are both dated 1794 by Blake, but the order in which he produced them is not immediately clear. Keynes sequences the books America, Urizen, Europe, The Song of Los, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los (222-48). By placing Urizen between America and Europe, he implies that the continental cycle was Blake’s most recent project when working on The Song of Los and that he postponed work on the subsequent books of Urizen. Erdman and other editors are less clear about the sequence of the 1794 and 1795 books; they group the related books together, even though that means placing Urizen after The Song of Los so it can be read with The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los and The Song of Los can be read with America and Europe. In the Blake Archive, we place Europe before Urizen, assuming a chronological contiguity with America because the works are physically, visually, and thematically alike, but also because the Urizen plates were executed in terms of color printing, the printing technique Blake had begun using in 1794, and the Europe plates were not (see Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, chapter 29). The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania are thought to be last because they are intaglio and short, supposedly representing a decreased focus on illuminated book production. An easy symmetry and progression, from large format to small, relief etching to intaglio—and then no more illuminated books until Milton (c. 1804-11)—helps make this sequence attractive. But when examined in terms of their production, these books reveal a much different sequence, one in which The Song of Los is executed last, the “Urizen” project is completed uninterrupted, and the return to the “continental” project is possibly an afterthought.

I will begin by recapitulating the main argument of my bibliographical analysis of The Song of Los, in which I realize digitally the book’s virtual designs and original format, then proceed to examine the technique of the color-printed drawings, reconstruct the sheet of copper from which Blake cut The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania, provide new information about the trial proof for Pity, Albion rose, and the Large and Small Book of Designs, and conclude by speculating on the sequence of the three illuminated books and their relations to the large color-printed drawings.

I. Blake’s Reconstruction of The Song of Los

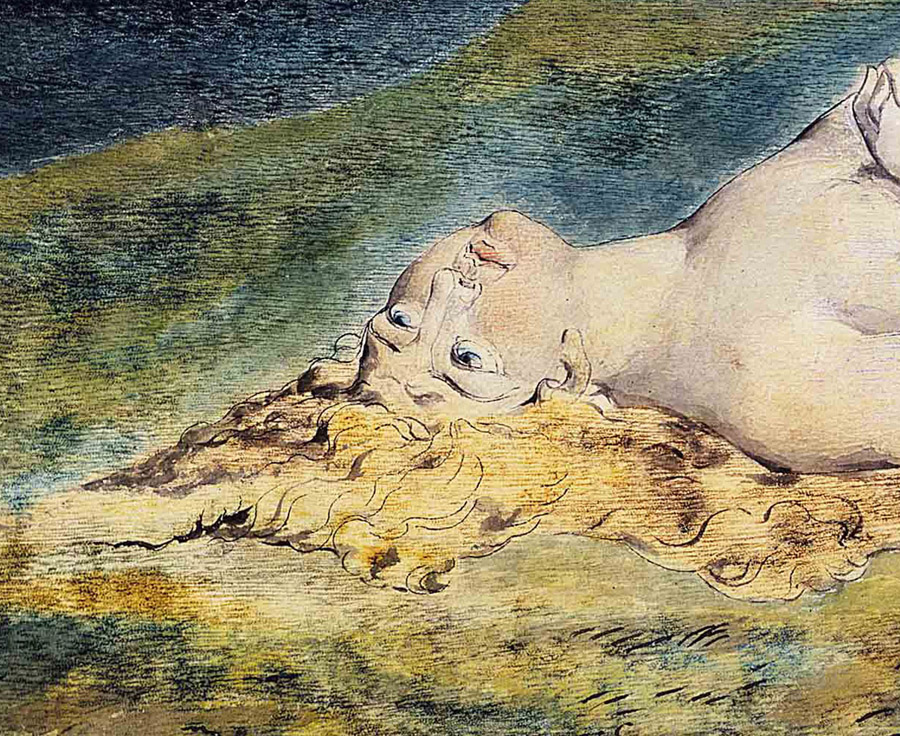

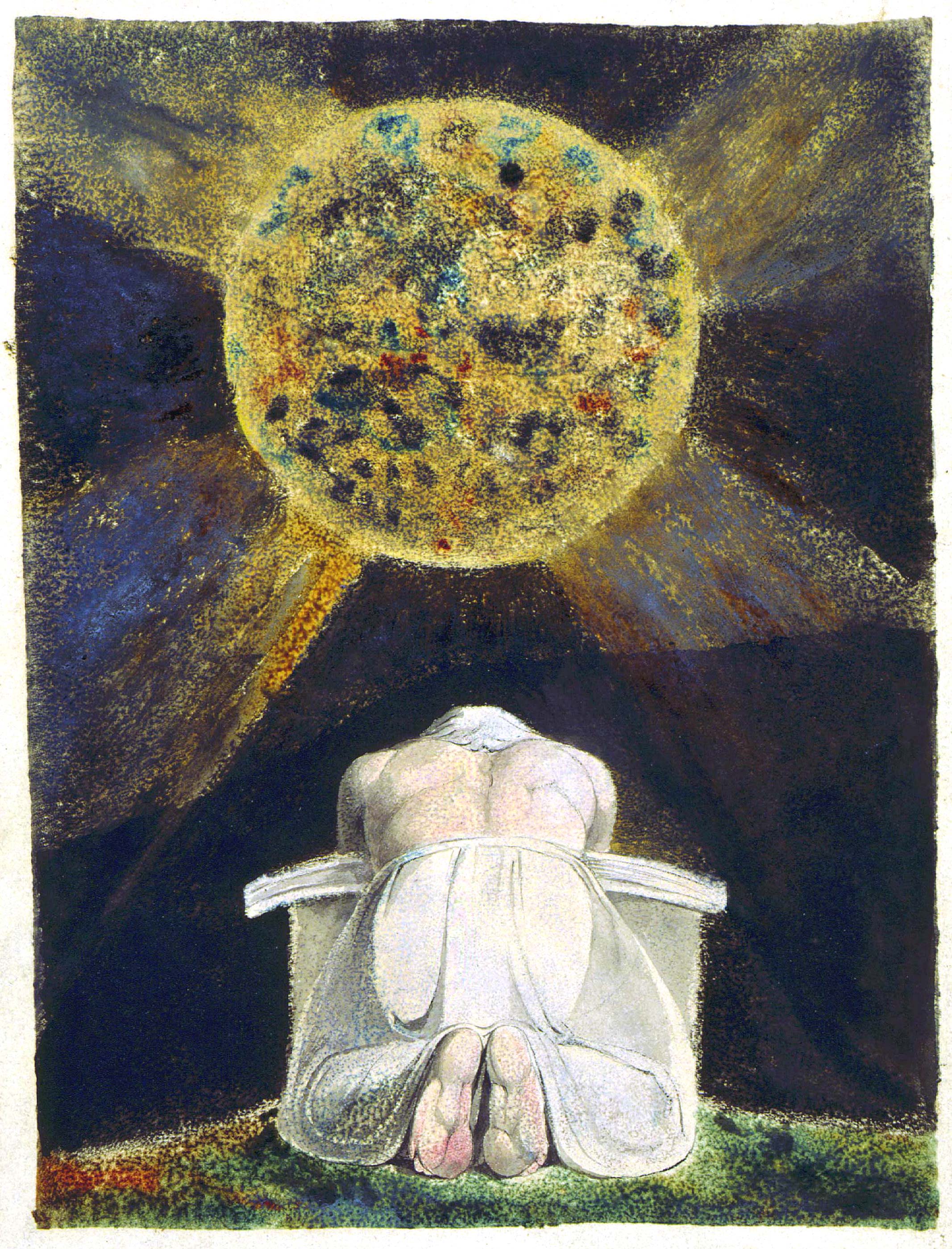

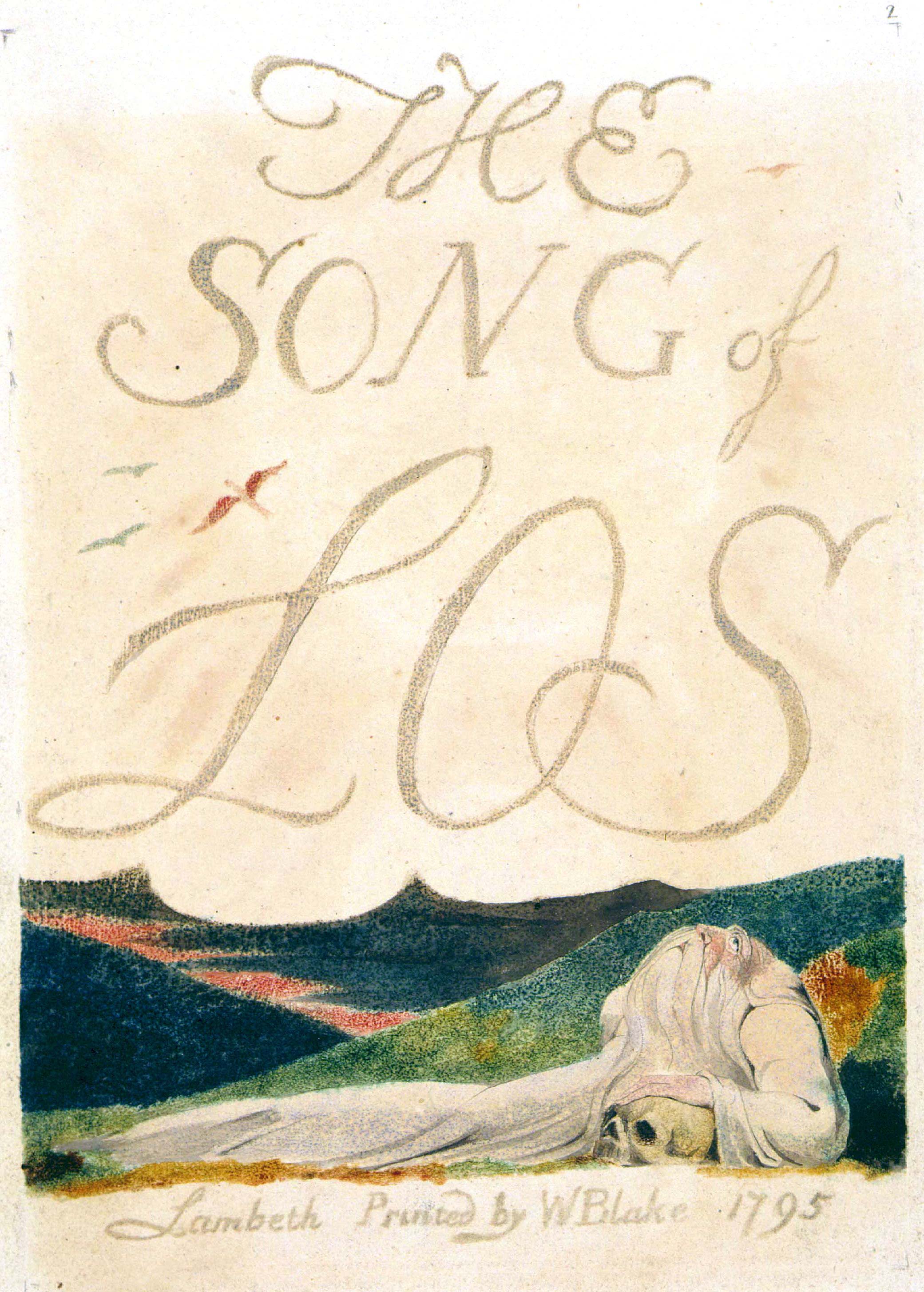

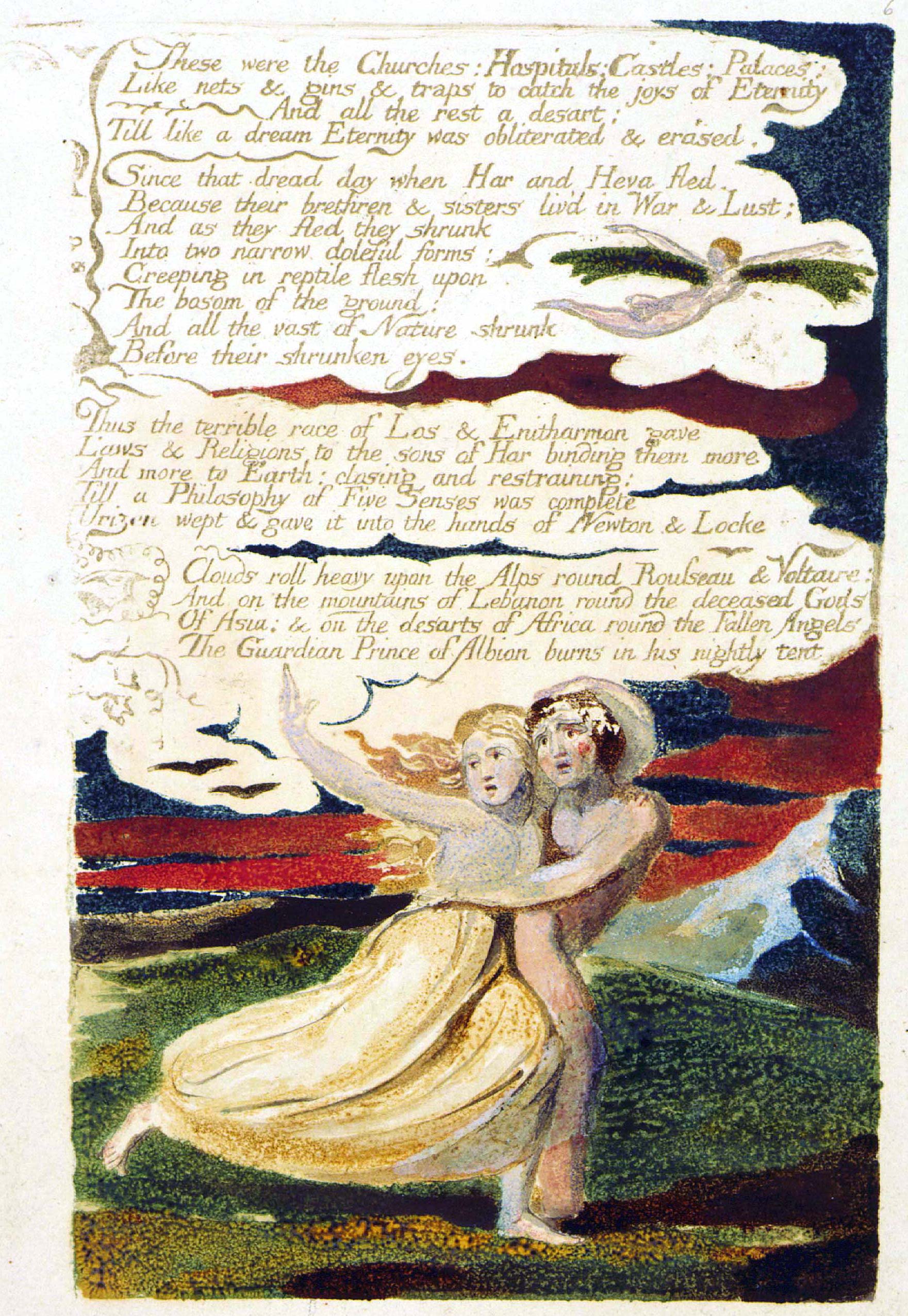

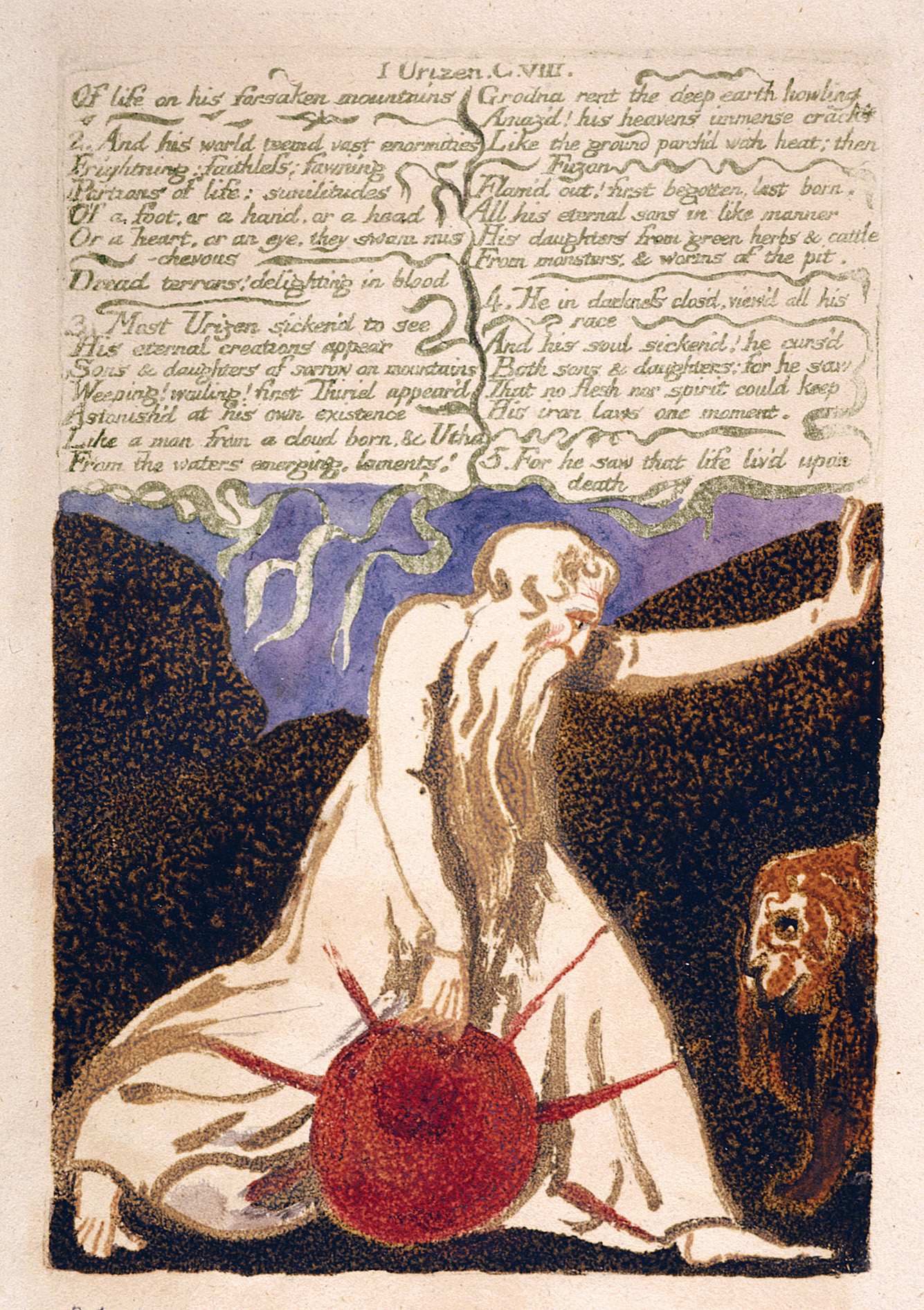

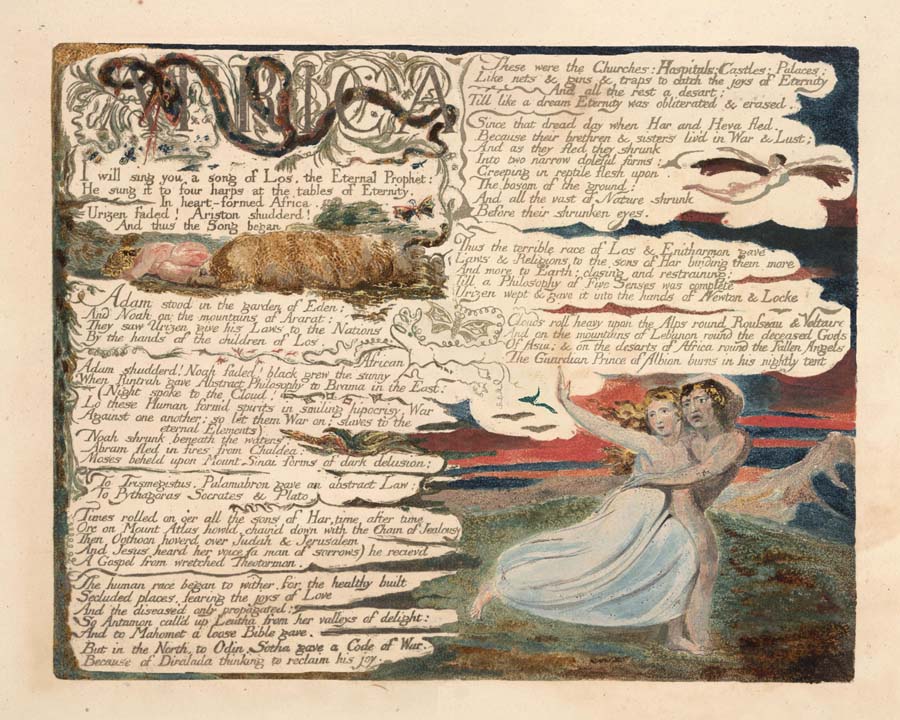

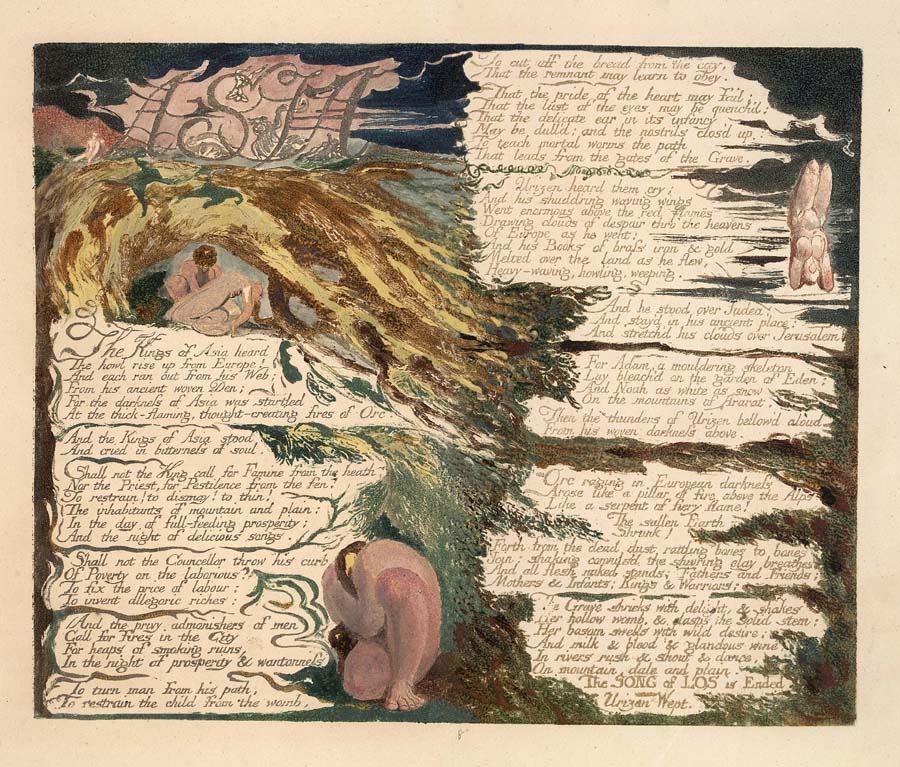

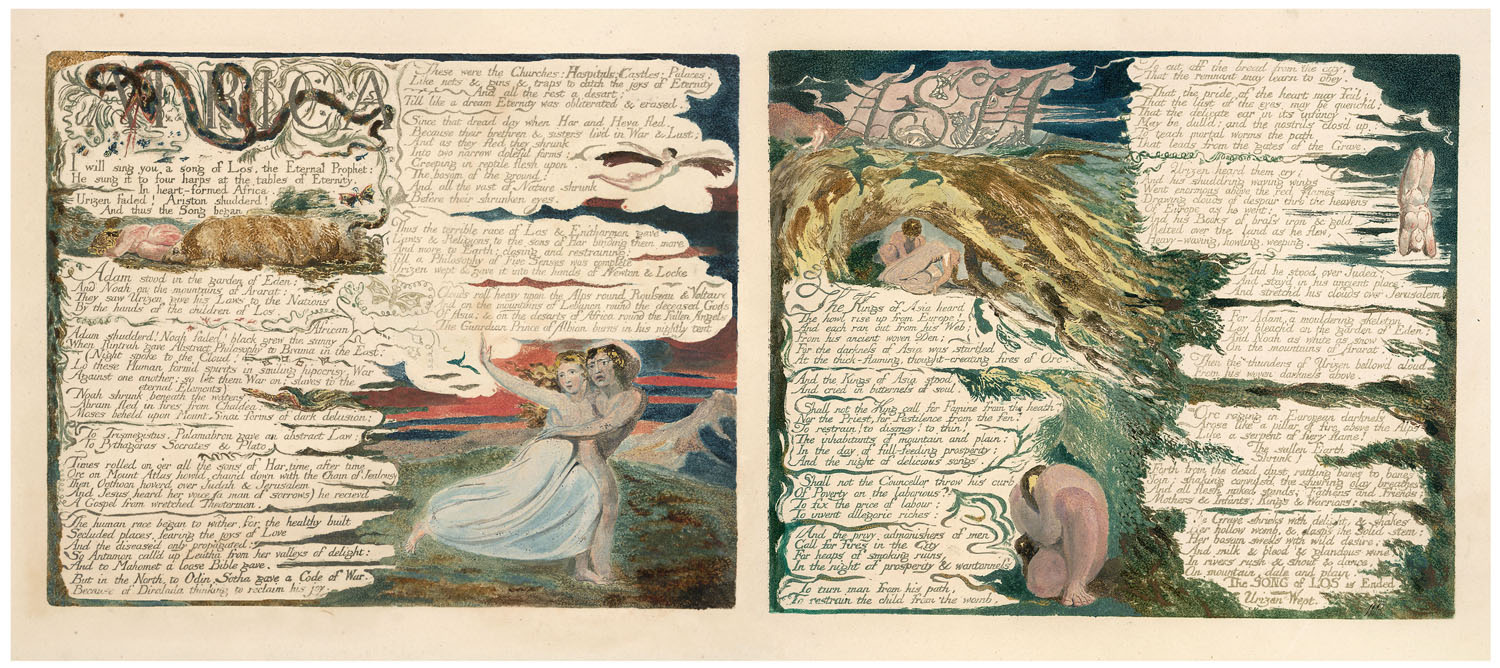

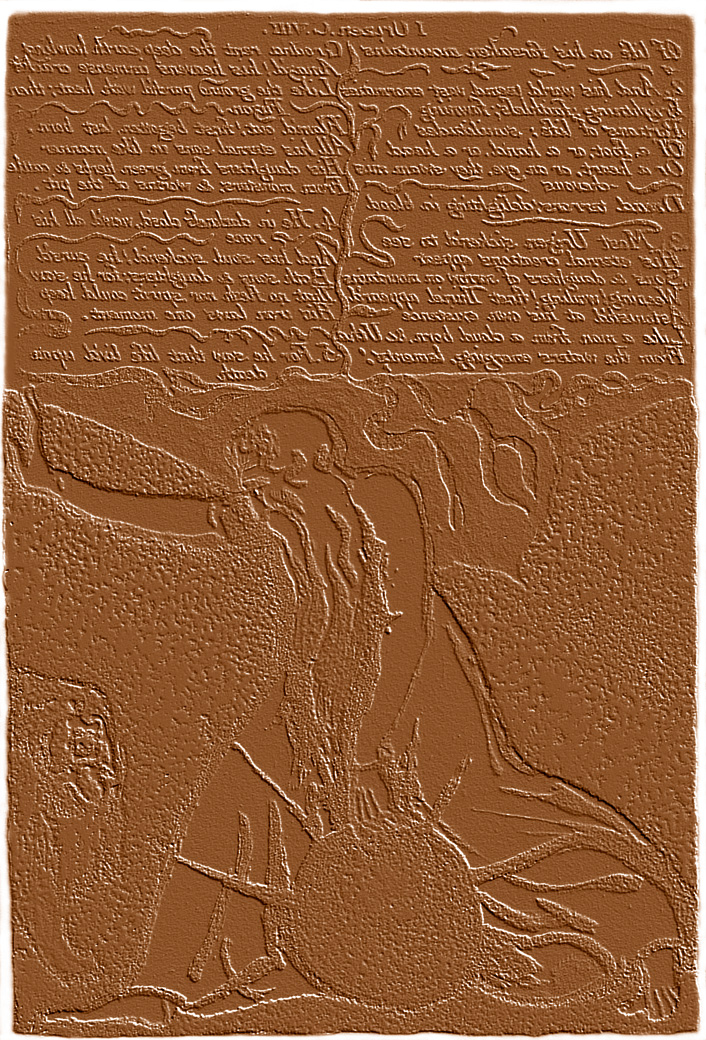

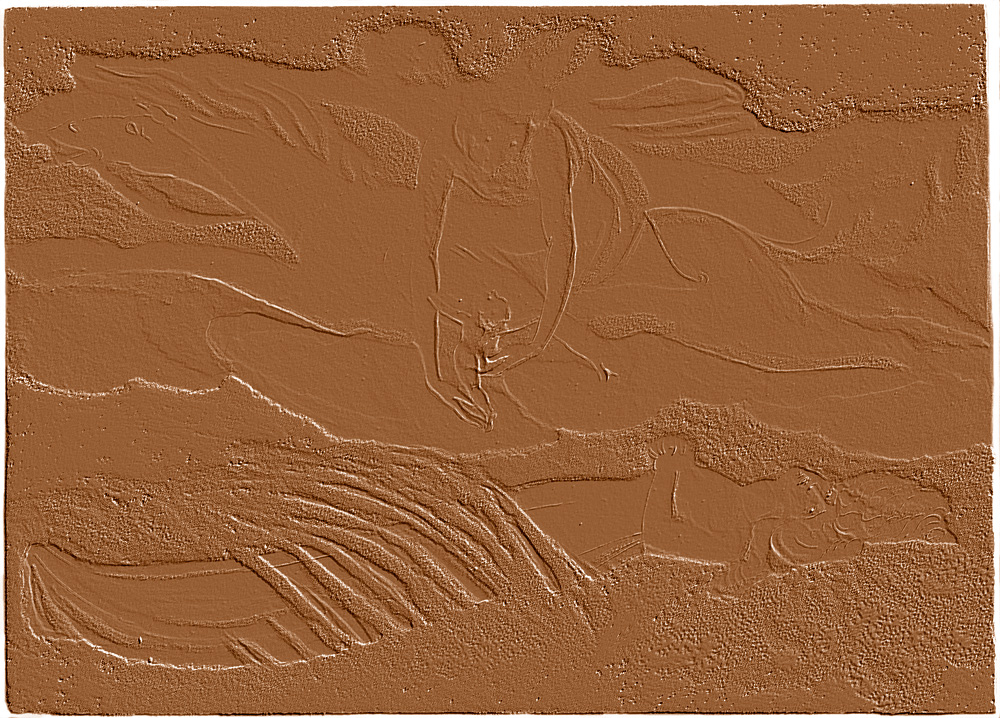

The Song of Los, dated 1795 on its title page, is Blake’s most oddly shaped illuminated book, consisting of four full-page illustrations (including the title page) and four text plates, which are about 4 cm. narrower than the illustrations and 1 to 2 cm. shorter. As I have shown elsewhere, illuminated plates are never perfectly uniform or square, because Blake cut most from larger sheets by hand.3↤ 3. See Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book, chapter 5, and “Evolution” 306-07. But the variance among plates is greatest in The Song of Los—and, as we shall see, is actually much greater than it first appears. The frontispiece (illus. 1), picturing Urizen kneeling at an altar under a globe inscribed with strange markings, is the exact same size as the endplate (illus. 2), picturing Los kneeling above the sun, hammer in hand. Figures with globes in mirrored position pair the designs visually and thematically and suggest a new, conflated virtual design (illus. 3). Plates 1 and 8 are the same size because begin page 53 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

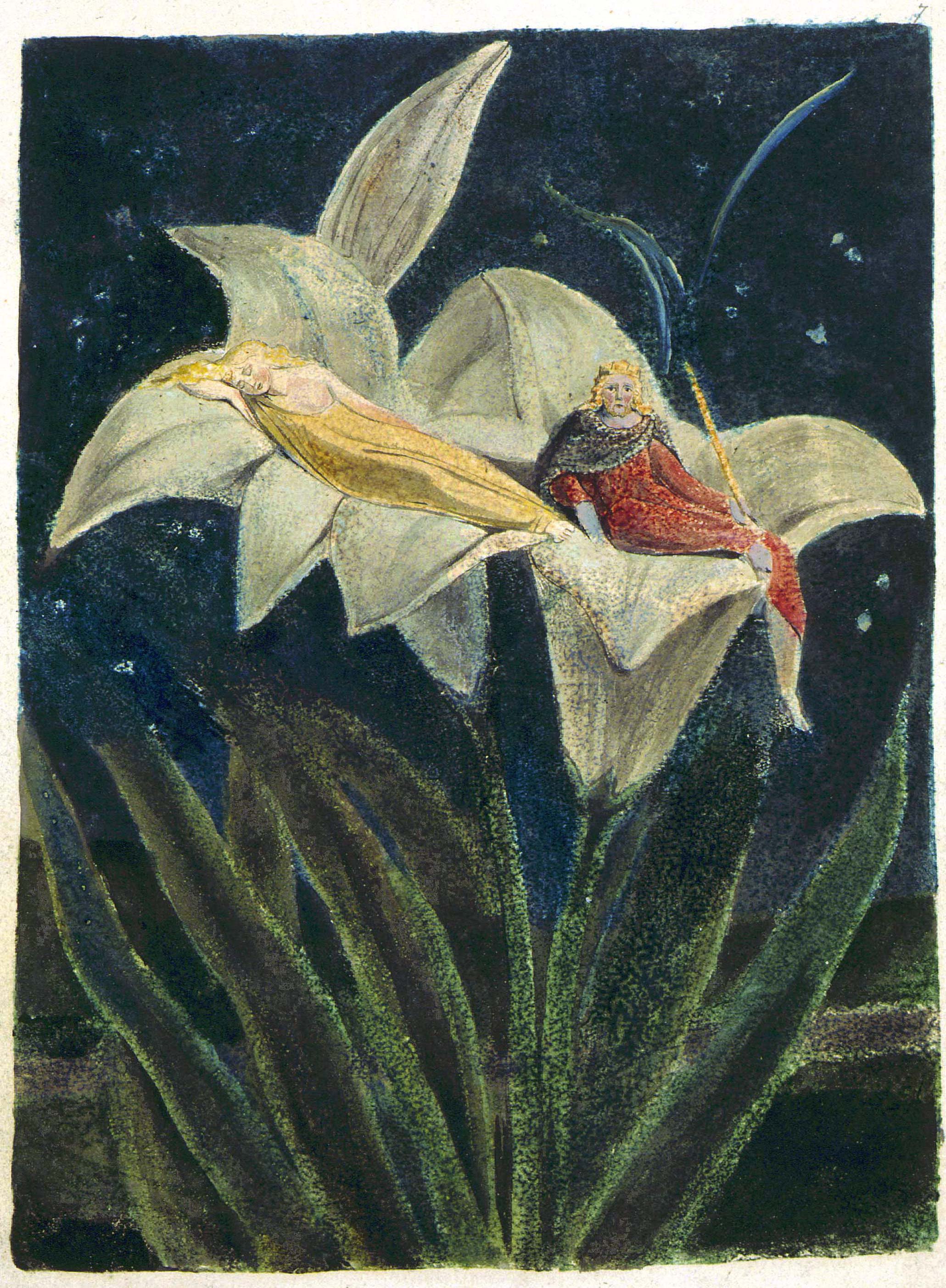

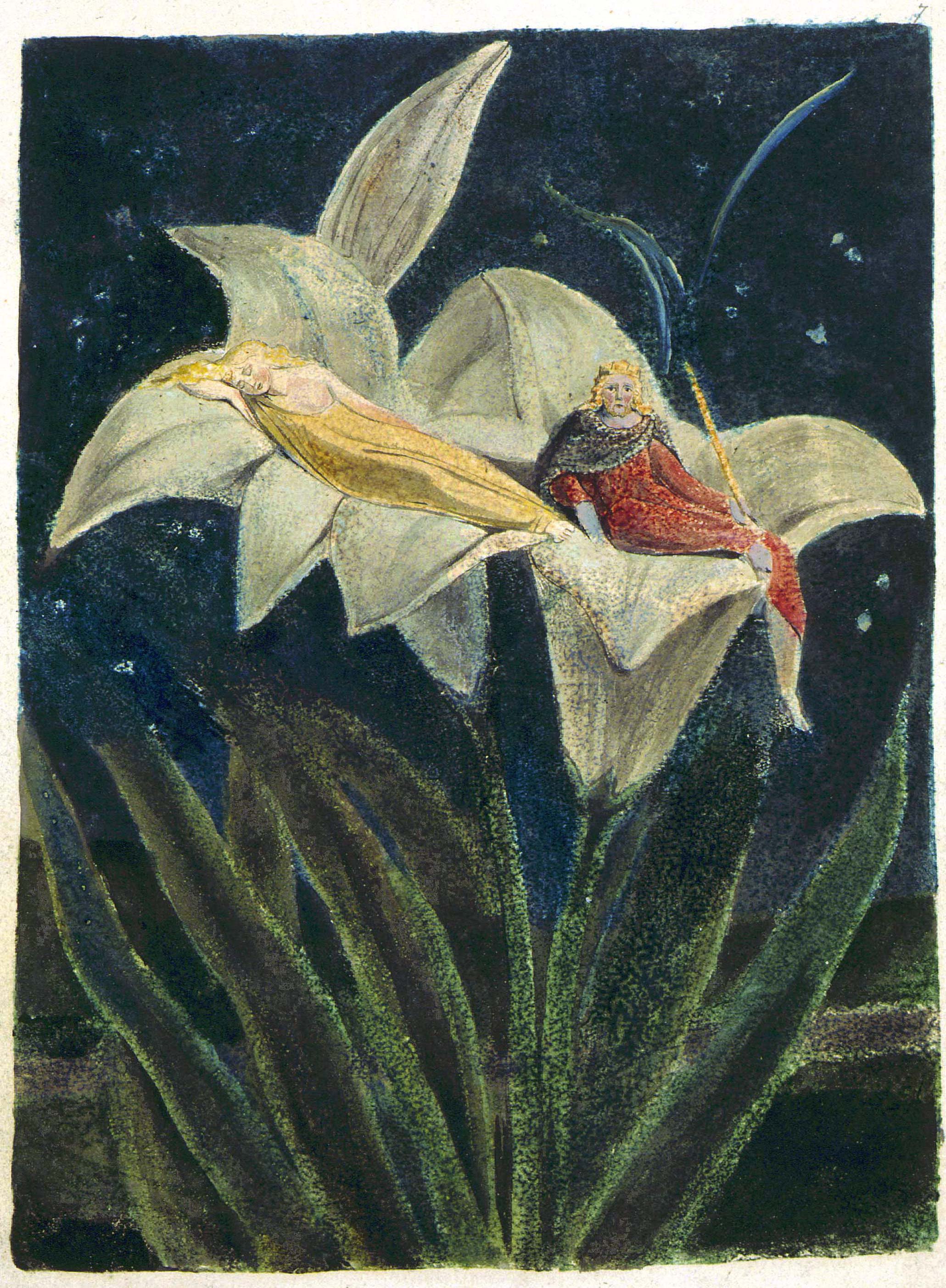

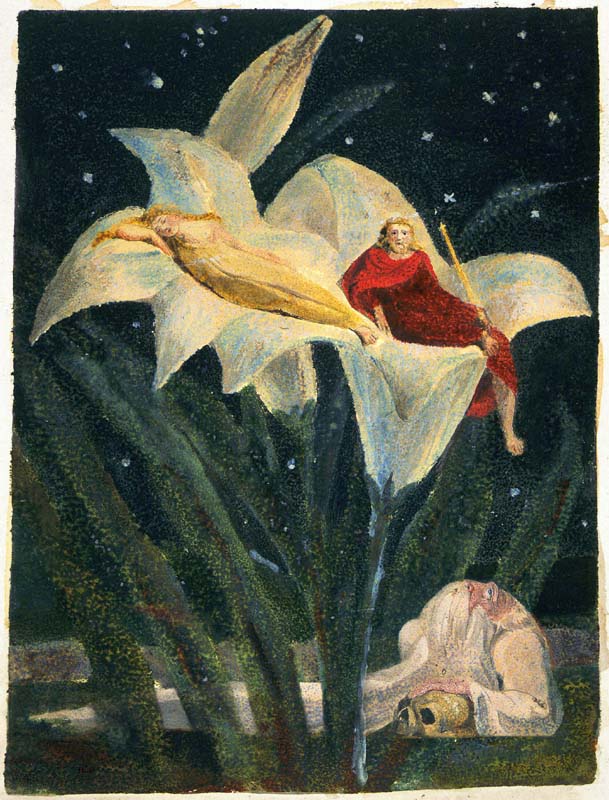

Blake typically etched both sides of relief-etched plates: Experience plates are on the versos of Innocence, Europe on America, Urizen on Marriage. Thus, discovering that plates 1 and 8 were etched recto/verso was not surprising. Finding plates 2 (illus. 5) and 5 (illus. 6), the other two full-page illustrations, apparently not recto/verso, however, was surprising. They have the same shape and width, but plate 5 is 9 mm. shorter. The discrepancy is an illusion, however, caused by the top of plate 5’s having been masked 9 mm. upon printing.4↤ 4. The masking is very difficult to detect, but the plate’s embossment is visible in the verso of the copy C impression, which reveals the plate’s true size as well as a 4-5 mm. dent in the plate’s edge (illus. e7), which would have been unsightly and distracting had it been printed as part of the heavily color-printed plate 5. The bottom of plate 2, however, was not color printed and thus could be printed without showing the dent. This is not the first time Blake masked top or bottom of a design. He had masked the bottom of America plate 4 in its first printings of 1793 so that the last five lines did not print (Bentley, Blake Books 87). The plates are recto/verso, with the top of plate 5 being the bottom of plate 2. Together, this recto/verso pair form a virtual design in which Urizen is imprisoned behind the leaves of the lilies holding Titania and Oberon (illus. 8), calling to mind the imprisonment of another eternal in Urizen plate 4 (illus. 9) and the body behind

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

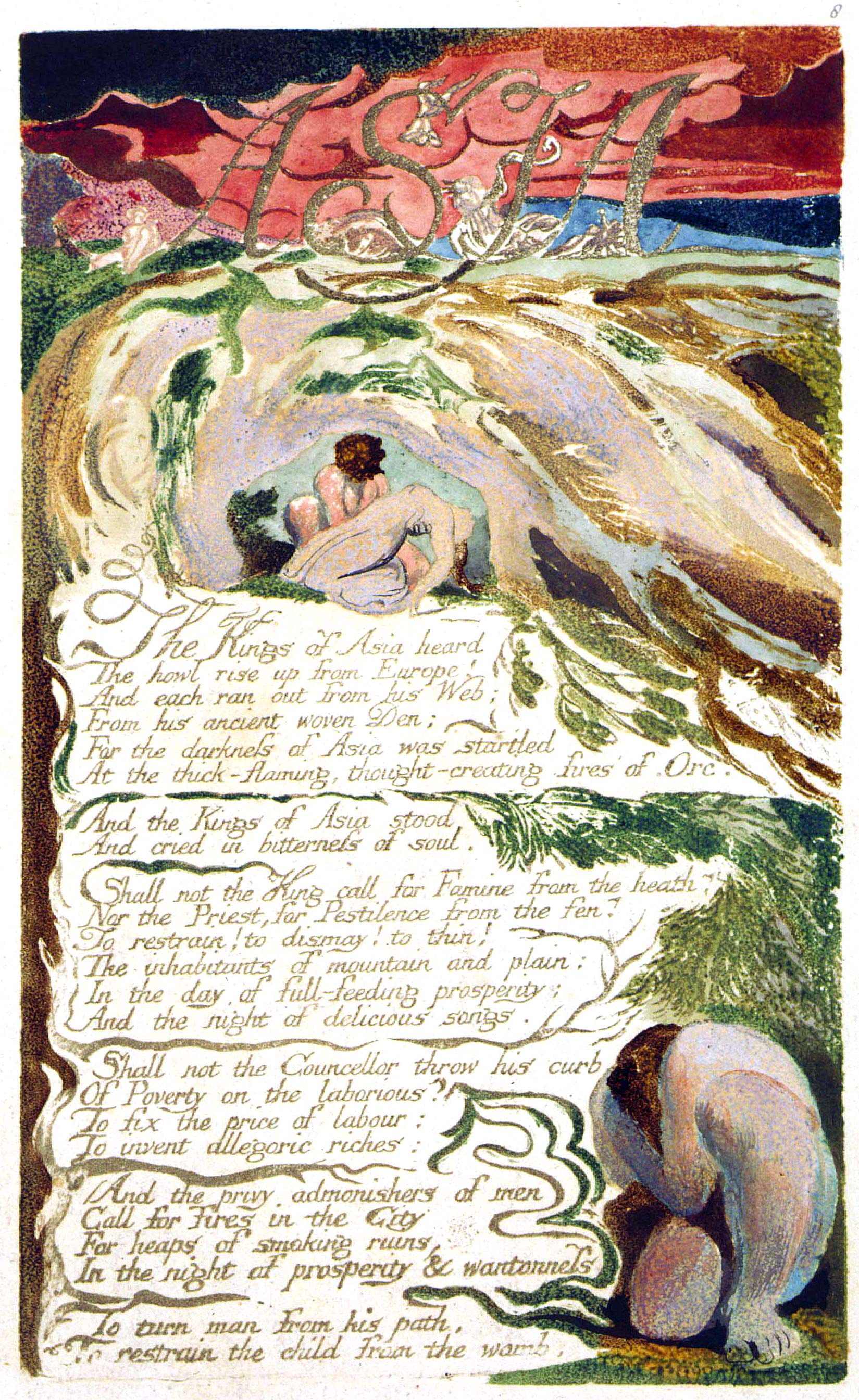

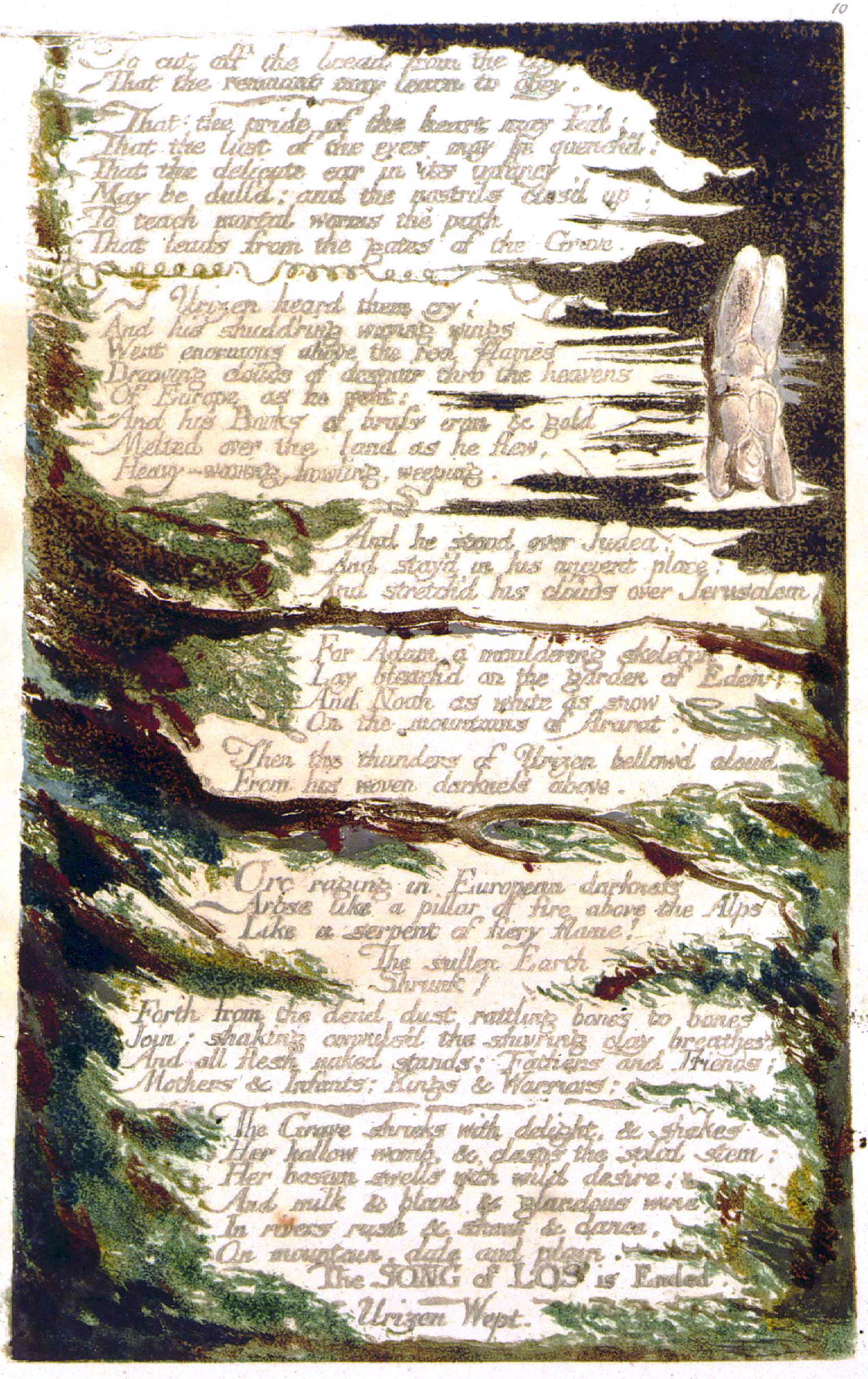

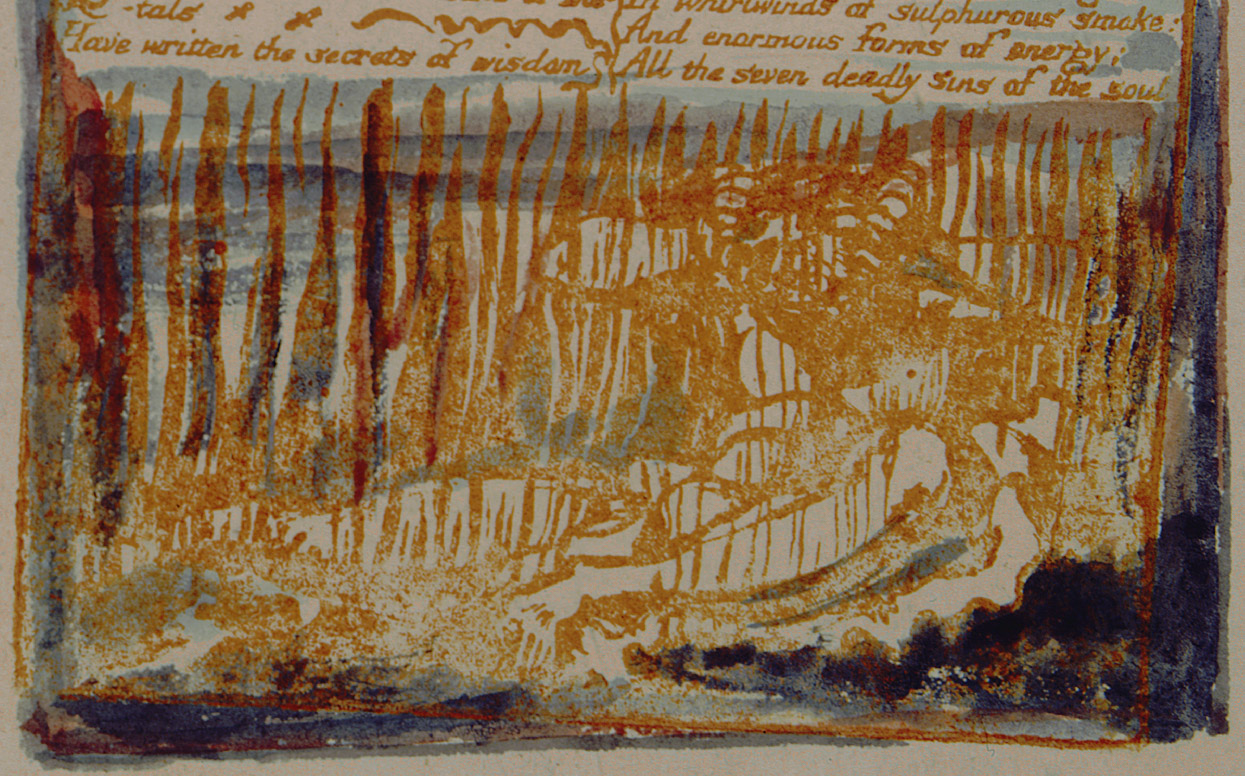

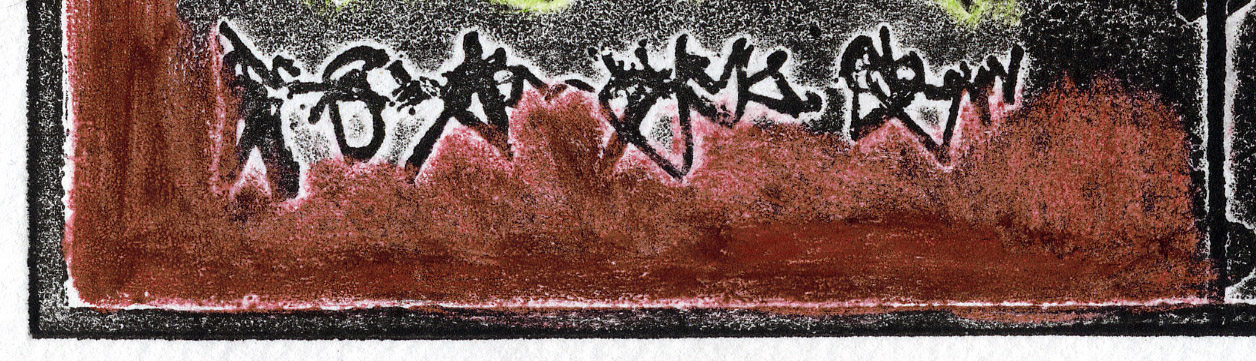

Erdman sees a virtual design formed of plates 6 (illus. 11) and 7 (illus. 12). He notes that plate 7 “seems to continue the forest of plate 6; the boughs that crowd the left margin—an unusual effect—can be the ends of those bent down in the right margin of 6” (Illuminated Blake 180). Envisioning plate 7 to the right side of plate 6 actually corresponds to Blake’s design as originally executed. These two plates, which form the poem or section entitled “Asia,” are actually the left and right sides of one horizontal design, as are plates 3 (illus. 13) and 4 (illus. 14), which form the poem or section entitled “Africa.” The “Africa” design is 21.5 cm. left, 21.5 cm. right, 27.3 cm. top, 27.2 cm. bottom; the “Asia” design is 22.2 cm. left, 22.2 cm. right, 27.2 cm. top, 27.4 cm. bottom. Instead of being recto/verso, as one would expect, the text plates are actually only half their original designs; as conceived and etched, “Africa” and “Asia” are autonomous designs clearly related to one another visually but not materially. I discovered these interesting material facts in 1991 and published them two years later begin page 58 | ↑ back to top

Blake initially divided his text into two columns, but very unlike the columns in Urizen, these being very loosely placed across a horizontal—or “landscape”—format, a format used for paintings and prints but not the text of books. By masking one side of the design, probably with a sheet of paper, he was able to print each text column separately. Hence, he transformed a coherent design 27.2 cm. wide into two seemingly independent designs/pages approximately 13.6 cm. wide, which is nearly 4 cm. narrower than the four illustration pages. He produced The Song of Los using just four plates, but two are portrait format and executed recto/verso and two are landscape format and apparently executed using one side only. Why create pages in oblong folio format, with double columns, so visually different from the pages of America and Europe? Why print the columns of text separately after composing and etching them as part of the same design?

begin page 59 | ↑ back to topGiven the two distinct sets of plates, The Song of Los appears to have emerged from two distinct stages of production, with the text plates coming first. This sequence seems the most likely, because if Blake had the two portrait plates on hand, intending to use them for the designs of his new book, then he would have acquired plates for texts to match. If, along with the portrait plates, he also had the 27.2 cm. plates on hand, then he probably would have cut them approximately 17.5 cm. wide and etched both sides to create four text plates to match the width of his illustrations, thereby producing a book of eight pages much nearer in size and shape to America and Europe. It seems reasonable to assume, then, that the two portrait plates were not yet on hand, that the two 27.2 cm. wide plates were acquired first, and that the text plates preceded the illustrations. (As we shall see, the shared width of these plates is not a coincidence; at least four other plates from 1795 share the exact measurement of 27.2 cm., including the sheets that yielded the plates for The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania.) Moreover, from this perspective, Blake appears to have set out to fuse poetry, painting, and printmaking in ways even more radical than the illuminated books. “Africa” and “Asia,” as originally executed, function autonomously as painted poems or written paintings, with text superimposed on a landscape design. Each design could have been matted, framed, viewed, and read like a separate color print or painting. They do not, however, function as book pages.

Blake created relief etching as a way to work as a printmaker with the tools of the poet and painter, that is to say, with pens, brushes, liquid ink, and colors, rather than the burins and needles conventionally required of metal. Blake worked on rather than in the metal surface, as though it were paper, with tools that enabled him to work outside the conventions and codes of printmaking and indulge his love of drawing and writing. His new medium encouraged the autographic gesture, the calligraphic hand of the poet with the line and

Blake did not, however, design “Africa” and “Asia” as book pages; he transformed them into book pages through a trick of printing. Horizontal formats were commonly used for print series, particularly aquatints of picturesque views, but also for works like George Cumberland’s Thoughts on Outline, eight of whose illustrations Blake engraved in late 1795 and 1796. But, as mentioned, horizontal formats were not used for texts of books, nor does any book in oblong folio before 1795 with pages in double columns come readily to mind. Even stitched together to form a long open diptych (illus. 17), the two designs seem less like facing pages in a book than a long panel, pair of broadsides, or a horizontal scroll. Perhaps Blake used a non-Western book format to evoke Africa and Asia. For example, the Chinese horizontal scroll, usually on silk or paper, fuses calligraphy and painted image. It reads right to left, starting with the title panel, which names the work, and has a colophon panel, at the end of the scroll or juxtaposed over the image, which contains the poem or notes pertaining to the work. Blake titles his poems “Africa” and “Asia” and thus does not need a title page, which is a book convention. If he meant the poems to be read as parts of one work entitled “The Song of Los,” then that too is effected without a title page. “Africa” begins with “I will sing you a song of Los, the Eternal begin page 60 | ↑ back to top

Perhaps the two designs were meant to be joined and printed on one sheet to form a panorama, a format the landscape painters Paul Sandby and Francis Towne were experimenting with in the 1780s and 1790s, or, as noted, to suggest an ancient scroll, the predecessor of the printed codex, and thus a fitting medium for the Eternal Prophet. Indeed, “in the context of Romantic textual ideology,” according to Mitchell, “the scroll is the emblem of ancient revealed wisdom, imagination, and the cultural economy of hand-crafted, individually expressive artifacts” (65). For Blake, “the scroll represents writing as prophecy: it is associated with youthful figures of energy, imagination, and rebellion” (65). Printed together on one sheet of paper the designs form a long, narrow, perpetually open composition approximately 22.5 × 54.5 cm., which is half the size of most of the color-printed drawings; if given a centimeter between and around the images (illus. 19), the resulting two-part panel would be approximately half the size of Newton (46 × 60 cm.) or Good and Evil Angels (44.5 × 59.4 cm.), among the largest of the color-printed drawings. As originally designed, however, the two poems continuing Blake’s continental myth do not resemble the previous installments in size, shape, number, or structure. America with 18 plates and Europe with 17 plates are matched in size, shape, and structure: both begin with frontispiece, title page, two-page preludium (Europe’s plate 3 is a late addition, though one that gave Europe 18 pages), a heading of “A Prophecy,” and “finis” as the last word. The titles of The Song of Los sections clearly connect the poems/panels to the earlier works, but the horizontal format marks a break with them as well. The full visual extent of that break was not realized; instead, Blake executed four illustration pages exactly the size of America and Europe and printed each of the four text columns separately. The resulting eight pages of The Song of Los are frontispiece, title page, “Africa,” full-page design, “Asia,” end-piece; headings of “A Prophecy” or endings of “finis” are not present. As reconstructed, The Song of Los is unevenly shaped and oddly structured, being two poems in one book to form a quartet of continental works within a trilogy of artifacts.

Proofs of the text plates in their original condition, or “first state,” are not extant, which may suggest that Blake abandoned his experiment in rethinking text and image soon after completing the text plates. This, however, cannot be proven, since other plates are also without proofs. But it does seem reasonable to suggest that Blake reconstructed the text plates to salvage an experiment about which he had changed his mind. We can sequence and speculate upon the stages in the production of The Song of Los, but can we sequence those stages within the year’s worth of productions and discover the relation of the books to one another and to the color-printed drawings? These are the main questions I try to answer in the following five sections.

II. The Large Color Prints

The large color prints are, “as a group, the first really mature individual works in the visual arts that Blake created. Moreover they are, as a group, probably the most accomplished, begin page 61 | ↑ back to top forceful, and effective of Blake’s works in the visual arts” (Butlin, “Physicality” 2). Technically, they are monotypes, which are in effect printed paintings. Frederick Tatham described the process to Gilchrist accurately enough, stating that when Blake

wanted to make his prints in oil . . . [he] took a common thick millboard, and drew in some strong ink or colour his design upon it strong and thick. He then painted upon that in such oil colours and in such a state of fusion that they would blur well. He painted roughly and quickly, so that no colour would have time to dry. He then took a print of that on paper, and this impression he coloured up in water-colours, re-painting his outline on the millboard when he wanted to take another print. This plan he had recourse to, because he could vary slightly each impression; and each having a sort of accidental look, he could branch out so as to make each one different. The accidental look they had was very enticing. (Gilchrist 1: 376)To W. M. Rossetti, Tatham added that the printing was done

in a loose press from an outline sketched on paste-board; the oil colour was blotted on, which gave the sort of impression you will get by taking the impression of anything wet. There was a look of accident about this mode which he afterwards availed of, and tinted so as to bring out and favour what was there rather blurred. (Rossetti 16-17)Tatham is mistaken about the medium, which was gum and glue-based colors and not oil-based inks or colors, as are commonly used today for monotypes, and Blake would not have had to work too quickly or worry too much if his colors dried to the touch on the support, because he almost certainly printed on dampened paper, whose moisture would have reconstituted the colors.6↤ 6. Blake used damp paper to print both intaglio plates—which is standard practice—as well as his relief etchings (Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book 99-100). The facsimile of Albion rose and the color prints (illus. 18, 19, 21) in Essick and Viscomi, “Blake’s Method,” were printed on damp paper after the colors had dried. McManus and Townsend come to the same conclusion: “The paper was not prepared with any priming, but would have been wetted to make it more receptive to printing” (83; see also Ormsby and Townsend 44). For analyses of Blake’s colors in the large color prints, see McManus and Townsend 86-99, and Townsend 186. The colors, though, he applied “strong and thick” to create a unique spongy opaque paint film, but also to enable a second and sometimes a third impression to be pulled from the millboard without having to replenish the colors. Generally speaking, depending on the paper’s dampness and thickness and the amount of printing pressure, the colors are strongest in first impressions and less intense in subsequent pulls. The presence of lighter outline and colors in second impressions is proof that outline and colors were both printed together for the first impressions as well, even for the one color-printed drawing with a relief-etched outline, as will be demonstrated in illustrations below. Tatham is correct, then, to assume that Blake “drew . . . his design . . . [and] then painted upon that . . . [and] then took a print of that on paper,” as opposed to printing outline (“design”) and colors separately.7↤ 7. To print outline and colors separately calls for printing the plate twice. For Blake, this would have required printing the outline onto a sheet of paper, somehow fastening the paper in place on the press bed, marking the position of the plate, removing the plate to apply its colors, returning the plate exactly to its position (a hair-width variance at top or sides will reveal itself), and dropping the paper over the plate exactly where it was. Because the shape of the dampened paper is slightly altered by its first pass through the press, perfect (i.e., undetectable) registration is near impossible under the best of conditions. Evidence of a plate’s having been printed twice by hand is nearly always visible if you know where to look; the absence of such evidence signifies single-pull printing and is not evidence of Blake’s genius for hiding his hand in color printing. If outline and colors of lighter second impressions were printed separately, then both first and second impressions underwent a procedure that doubled the likelihood of misregistration. The first impression, instead of being fastened to the press, is removed so a second impression can be printed, thus the sheet of paper as well as the plate with colors must be aligned exactly, top and sides, to their marked positions, greatly increasing the chances of misalignment. No one explicitly argues for this mechanical and labor-intensive procedure for second impressions, which is wise, since no second impression among the large color-printed drawings or the Large and Small Book of Designs (see section V of this essay) shows any misalignment of color and outline. Yet such a procedure is implied because it is the inevitable and logical result of printing outline and colors separately. Hence, the premise of two pulls collapses when tested this far in practice, which in turn supports the one-pull hypothesis for both second and first impressions. For the fullest presentation of the hypothesis that Blake color printed his outline (which includes text when it is part of the relief-line system) and colors (which could be printed from relief lines and/or shallows) separately, registering the second pull on top of the first exactly, consistently, and without traces of this production method, see Phillips’ William Blake and “Correction” and Butlin’s “War.” For a refutation, see Essick and Viscomi’s “Inquiry” and “Blake’s Method.” He is also correct that Blake “tinted” the impressions “to bring out and favour what was there rather blurred.” As with his color-printed illuminated book impressions, Blake finished the large color-printed drawings in watercolors and pen and ink, clarifying forms in the blots and blurs. Translucent and transparent washes over mottled colors could also transform printed colors, making more colors appear to have been printed than actually were. Given that the method is primarily painting on a flat support and pressing that painting into paper, differences among impressions were inevitable if not also intentional, hence the oxymoronic term of monoprint, a print that is unique rather than exactly repeatable.

To use millboard to print colors requires at least minimal sealing of its porous surface. Blake could have done this with a coating of glue size or gesso, which is chalk or whiting mixed with size and painted over panels or canvas to produce a very white ground. Smith, Tatham, and Linnell mention Blake’s using this mixture to prepare his tempera paintings. According to Smith, “his ground was a mixture of whiting and carpenter’s glue, which he passed over several times in thin coatings” (Bentley, Blake Records 622). In his manuscript on the life of Blake, Tatham says “3 or 4 layers of whitening & begin page 62 | ↑ back to top

The striations in the surfaces of The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (illus. 21) and Christ Appearing to the Apostles (illus. 22) suggest that Blake painted his large color-printed drawings on gessoed grounds. Butlin notices “a striated” effect in Pity, as well as in impressions of Newton and Nebuchadnezzar (cat. 311, 307, 302), but believes it may have been “produced by only partial adherence” of paint to paper “as if the paper were slightly oily” (“Physicality” 17). The striations, though, appear not to have been created by the paint layer, but by the textured surface of the millboard, because the same striated patterns are visible across different printed colors, as is clear begin page 63 | ↑ back to top

But whether he used glue size or gesso, or thought of the millboard surface as canvas or panel or plaster wall, he needed an outline to know what to paint. Chalk or charcoal serves this purpose in oil painting, but lines made with either medium could be ruined in color printing and thus make returning to the design years later (as we know Blake did, around 1805) impossible (Butlin, “Newly Discovered Watermark” 101). He could have perhaps relied on the thin dried colors on the millboard, but it is more likely that he had an impervious outline to guide his hand. Some X-radiographs reveal traces of a lead-based paint, which may have been used for outlining, while others show no traces of lead, supporting the idea that the outline was executed in an ordinary water-based “Indian ink,” which is lead-free and thus not detectable (McManus and Townsend 87). Indeed, the “Indian ink” used to sign color

What Tatham describes is planographic printing, that is, printing outline and colors not only together but also from the same flat surface, with outlines neither raised—as in woodcuts or relief etching—nor incised—as in etchings and engravings.10↤ 10. Printing exactly repeatable images planographically is, of course, lithography, invented accidentally in 1798 by Alois Senefelder and initially called “polyautography” to suggest the autographic gestures of writing, drawing, and sketching. Senefelder intended initially to etch designs in low relief on metal or limestone and only accidentally discovered that designs drawn on soft limestone in a greasy ink absorb the printing ink while all untouched areas repel ink if first covered with a thin film of water. The basis of lithography, in other words, is the separation of water and oil. For more on Senefelder and lithography’s similarities to Blake’s relief etching, see Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book 24-25, 171-72; for information on Blake’s lithograph, Enoch, see Essick, Separate Plates 55-59. Blake had tried his hand at planographic printing before 1795, possibly as early as 1789, in a print entitled Charity. Identified as a “planographic transfer print” (Essick, Separate Plates 10), the image was first painted on a sheet of paper or millboard and transferred to the paper while the ink was wet. Counterproofing (placing face down) newly printed impressions—regardless of matrix—works the same way, wet ink transferred from a flat surface to paper, reproducing all marks and forms, albeit in reverse. Blake did not, however, begin page 64 | ↑ back to top systematically experiment with printing painted images until he color printed the etching Albion rose, which, as I argue below, was in 1795 and not 1794, as is supposed (Butlin, “Physicality” 3; Bindman 476), and which was executed with small Pity (illus. 10), the trial proof for the large color print. Until then, Blake had color printed only illuminated books with relief-etched plates. He inked outlines with dabbers and on and in small areas added colors, probably with stump brushes (brushes with the tips cut off) or poupées (tightly rolled felt), to small, well-defined forms. This is, as I have demonstrated elsewhere, a variation on à la poupée printing, in which an intaglio plate is inked in numerous colors (Blake and the Idea of the Book, chapter 13). It differs from conventional color printing, however, in that Blake put colors in spaces meant to be white and negative spaces defining forms, whereas in conventional color printing colors are applied to the lines of the design itself and not surfaces or white spaces. Adding colors to shallows and printing them with inked outline is radical,

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

At least one of the 12 large color-printed drawings, however, was not printed planographically. God Judging Adam (illus. 24) has traces of an embossed outline, indicating that the support was metal, probably copper, and that the outline was etched in low relief; it also has a platemaker’s mark (illus. e25), indicating that it was printed from the sheet’s verso. For the only color-printed drawing known for sure to have been relief etched to be on a sheet’s verso suggests that Blake was probably unsure of himself, continuing the experiments started with the small trial proof for Pity, which was also etched in low relief (see below), and intending to preserve the recto, the side normally used for engravings and etchings, should the experiment not work out. begin page 65 | ↑ back to top God Judging Adam is 43.2 × 53.5 cm. Because it is the only impression certainly to have come from a metal plate—and metal is much more expensive than millboard—Essick believes it was most likely the first of the large color-printed drawings executed (“Supplement” 139).11↤ 11. Today, an 18 × 24 in. sheet of copper (16 gauge) for etching costs almost $100; millboard nearly twice that size is less than $5. This is probably so, as will be shown below, but its place in the sequence is suggested by its technical connections to earlier experiments in color printing and not by its support, for two other designs may also have been printed from metal. Though printed planographically, Satan Exulting over Eve, at 43.2 × 53.4 cm., and elohim Creating Adam, at 43.1 × 53.6 cm., are the same size as God Judging Adam, raising the possibilities that one of these designs is on its recto and the other on a copper sheet acquired at the same time.12↤ 12. These measurements are from Butlin’s catalogue raisonné; I did not have the opportunity to measure each side of the impressions, which I assume would vary slightly. If either Satan or Elohim was printed from a copper matrix, then Blake not only used metal before millboard, but he also printed planographically from metal before millboard.

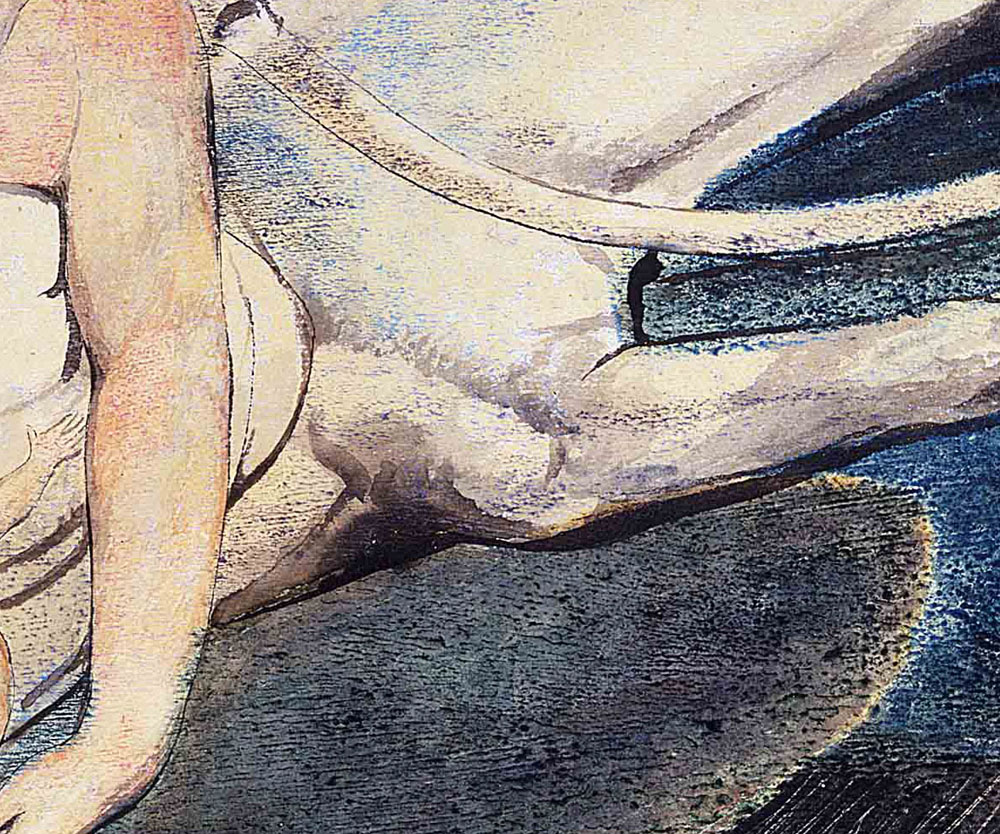

The detail of the horses’ heads in the first impression of God Judging Adam (illus. 26) reveals clearly that Blake applied a black paint to the low relief outline and shallows simultaneously and then added a brownish red to the shallows forming the neck and shoulder and a bright red to the manes. These steps in the painting process are even clearer in the second impression (illus. 27), which is, as noted, proof that both outline and colors were printed simultaneously here as well as in the first impression (see note 7). He probably applied the black with a small dabber, as in the illuminated plates, touching down in the shallows but not depositing color along the base of the relief lines, which produces a thin unpainted line on both sides of the outline. A yellow wash applied over the colors on the second impression is very bright in this line because it adheres to the untouched white of the paper. This halo-like line is evidence of a relief outline as well as of outline and colors’ having been printed together, as is demonstrated by an impression printed in one pull from a design etched in low relief, inked with a dabber in black, and painted in brownish red (illus. 28a). Had outline and colors been printed separately, the fine white line could not parallel the outline exactly, even with perfect registration, because the paper’s shape and dampness are slightly altered by its being pulled through the press, which is particularly noticeable in large sheets. Even when paint is deposited with a brush along the base of a relief line, paper is unlikely to pick the color up as it bends over the relief line onto the shallow, unless the paint is very thick. On plate 7 of The Song of Los copy E,[e] for example, Blake most likely used a brush to apply color to the tendrils dividing the verses, depositing paint on both sides of the relief line (illus. 28b), which, when printed, produced the telltale white lines and two tendril-like lines that printed from the shallows. Had Blake deposited color on one side of the outline only, the tendril-like

As noted, Blake did not need or intend to print outlines separately, not in illuminated books or color-printed drawings. In the latter, he only needed fixed guidelines for painting and for ensuring that the design, however it was colored in and/or finished, was repeatable. But when and how did Blake realize that if he “drew. . .his design. . . [and] then painted upon that” he could take “a print of that on paper,” that outline and colors could be on the same surface and he could paint over the outline with a brush rather than use a dabber? When did he realize that he was no longer painting a print but printing a painting? To answer these questions requires knowing where God Judging Adam fits into this evolution and how it connects to Albion rose and the small trial proof of Pity, which have a heretofore unknown connection to Blake’s intaglio books of 1795.

III. The Book of Los, The Book of Ahania

Three color-printed drawings, God, Satan, and Elohim, possibly all from metal and the first executed, are approximately 43.2 × 53.5 cm. This is a large but apparently not uncommon sheet size. Blake’s engraving of Beggar’s Opera Act III (1788) is 40.1 × 54.2 cm.; Job and Ezekiel engravings of 1793 and 1794 are 46 × 54 cm. and 46.4 × 54 cm. respectively; the plates for Stedman’s Narrative, 16 executed by Blake between 1792-94, average 27 × 20 cm., which suggests that they were quarters of a 40 × 54 cm. sheet of copper.13↤ 13. Eleven of the 16 plates are between 27.2 and 27.5 cm. in height, 3 are between 26.5 and 26.9 cm., and 2 are between 25.7 and 26.4 cm. Widths range only between 19.6 and 20.5 cm. I am indebted to Robert Essick for measuring his uncut copy of Blake’s engravings for Stedman. In most copies, the prints were trimmed to the design and thus shorn of their platemarks. If the Stedman plates, which were commissioned by the publisher Joseph Johnson, were quarters, then the platemaker from whom Blake bought the plates was most likely responsible for quartering the sheets, presumably according to either Johnson’s or Blake’s instructions, and may also have been responsible for preparing them for intaglio etching by beveling the sides and rounding the corners. According to Mei-Ying Sung, most of the Book of Job plates were cut by the platemaker, but crossing marks on the versos make it possible to reassemble them into their original sheets (“Technical and Material Studies of William Blake’s Engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job [1826],” Nottingham Trent University PhD, 2005, appendix 1). In some cases, in other words, Blake’s plates can be reconstructed into their original sheets whether Blake cut the sheets or had them cut for him. The larger widths, up to begin page 67 | ↑ back to top

These plate arrangements are not from Blake and the Idea of the Book, where I used just two measurements per plate and thought the sheet was larger and cut into sixths rather than quarters (414n26); they are from research done soon afterwards for David Worrall’s The Urizen Books. I used four measurements per plate and tracings of their shapes to reconstruct the sheets, the technique I had used to reconstruct the sheets that yielded the 27 plates of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.14↤ 14. This information about sheet reconstruction was first presented as a plenary address for William Blake 1794/1994, a conference at St. Mary’s College, Strawberry Hill, London, 14 July 1994, and later published as “Evolution.” Worrall agreed with The Book of Ahania arrangement (191) but not with The Book of Los arrangement (223n13), which is understandable since measurements, even with tracings, can support different results. With digital imaging, however, and the expert assistance of Todd Stabley, media consultant for my university, I was able to verify my earlier findings and to raise the bar for proof. Though it was no easy task, we were able to put the pieces back together. We verified the recto/verso plates by superimposing them, as with The Book of Ahania plates 3 and 2 (illus. e32), to reveal their matched shapes. We demonstrated, by revolving the plates, how their edges fit together, as evinced by the inside edges of The Book of Los plates 3 and 4 (illus. 33) paralleling one another exactly, one curving with the other.

With four plates 27.2 cm. in width (two for The Song of Los, one each for The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania), it seemed reasonable to assume that they were quarters of a sheet the size of—and perhaps acquired at the same time as—those used for the first color-printed drawings. The problem here, though, was an approximately 8 mm. difference in the heights of The Song of Los plates. If the measurements were correct, then one or both did not fit into the larger sheet. Moreover, the small, unfinished color print of Pity (illus. 10), recorded as 19.7 × 27.5 cm. (Butlin, cat. 313), was the same height as The Book of Ahania sheet, though 2 or 3 mm. wider, which I suspected was mistaken. The similarity of its size to the size of The Book of Ahania made small Pity seem likely to have been one of the quarters or, possibly, a quarter that was cut up to provide the plates for The Book of Ahania. Superimposing small Pity over The Book of Ahania plates revealed no convincing traces of small Pity. The digital reconstruction was beginning to reveal what combination of quarters was likely and unlikely to have come from the same sheet, as well as to reveal exactly what works I needed to reexamine. In the Morgan Library, I reexamined the height of the text plates in The Song of Los copy C, along with the size and shape of proofs of The Book of Los plates 4 and 5, and The Book of Ahania plate 5; in the Library of Congress, I reexamined The Song of Los copy B and again made tracings of the plates of the only complete extant copy of The Book of Ahania; most importantly, in the British Museum, I examined The Song of Los copies A and D, traced the plates of the only extant copy of The Book of Los, and determined exactly the size of the small Pity and Albion rose plates.

This new data enabled me to disprove my initial hypothesis that The Song of Los plates 3-4 and 6-7 and the plates for The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los were quarters of the same large sheet. It enabled me also to ascertain that small Pity was not the exact size of The Book of Ahania sheet but that it was one of the quarters. Two measurements for small Pity proved insufficient to see this connection, but with four it became clear: 19.75 cm. left, 19.5 cm. right, 27.2 cm. top, 27.4 cm. bottom. These are approximately the same measurements as the color-printed impression of Albion rose, which are 27.2 cm. left, 27.3 cm. right, 19.75 cm. top, 19.95 cm. bottom.15↤ 15. Essick records the plate size as 27.2 × 19.9 cm. (Separate Plates 24); Butlin records the Huntington impression as 27.2 × 19.9 cm. and the British Museum impression as 27.5 × 20.2 cm. (cat. 284, 262.1). Turn small Pity upside down and Albion rose on its left side, place them on top begin page 70 | ↑ back to top of The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania sheets (illus. 34), and you have the four quarters of a sheet that is 39.35 cm. left, 39.7 cm. right, 54.7 cm. top, 54.5 cm. bottom. Along the middle, vertically and horizontally, the sheet is 39.4 × 54.4 cm. This sheet was cut exactly in half and each half was cut in half, hence each of the four quarters has a side 27.2 cm. wide or high.

Why did Blake purchase a 39.4 × 54.4 cm. sheet of copper? At first, it may seem that he needed copper plates for his two new poems, The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los. The former has 239 lines and the latter has 176 lines, for a total of 415. Urizen is on 28 plates, 11 of which, including the title, are full-page illustrations, leaving 17 text plates for 517 lines. If Blake intended to etch his new poems in relief to match the style and structure of Urizen, then he would have needed at least 22 plates for the two books. Quartering each quarter of the large sheet produces 16 plates (or 32 if versos are used), slightly smaller than Urizen, whose size was determined by its being on the verso of Marriage plates, the size of which was determined by Approach of Doom quartered (see Viscomi, “Evolution” 307).

Deducing motive from end results, however, clearly does not work here. The sheet does not produce plates exactly the size of Urizen, forcing one to ask why not if that was Blake’s intent. More troubling is that Blake appears to have changed his mind after he quartered the sheet. Three of the quarters he intended to use for etchings or engravings, as indicated by their rounded corners and beveled sides, features designed to remove sharp edges that could tear the paper when intaglio plates are printed under the required pressure. One quarter he intended to use as a relief etching, as indicated by the absence of these features, which are unnecessary for relief etchings, because they are printed with less pressure. Given the manner in which the quarters were prepared—whether by Blake or a platemaker following Blake’s instructions (see note 13)—Blake appears not to have acquired this copper sheet as a poet needing many small relief-etched plates for an illuminated book; he appears to have acquired it as a printmaker, with at least two designs, Albion rose and small Pity, in mind, as a creative graphic artist who, to date, had executed many separate etchings and engravings, including Head of a Damned Soul (c. 1790), The Accusers (1793), Edward and Elenor (1793), Job (1793), and Ezekiel (1794).

begin page 71 | ↑ back to topWhat Blake originally intended for the other two quarters prepared for intaglio designs is not known. It is interesting to speculate, though, that the designs may have been The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (24.2 × 27.8 cm.) and Newton (20.4 × 26.3 cm.), which are the only other drawings extant that fit the quarters—or could be trimmed to fit—that were also executed, like small Pity, approximately four times their size as large color-printed drawings. But whatever the original plans were for these quarters, Blake changed his mind. He quartered the two quarters and used the resulting plates for The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania. This sequence of events is indicated by the fact that each small plate has just one rounded corner (illus. e35), that of its original sheet, which, in addition to the plates’ uneven and rough inside edges (illus. 33), is why the plates can be reconstructed like pieces of a puzzle back into their original quarter sheets (illus. 30, 31). The edges are rough because Blake did not file them at an angle (the bevel), and though he appears to have pounded down the sharp edges of the new corners, he did not round them. In other words, Blake did not prepare the small plates for etching.

Was he in such a hurry to print his new poems and designs that he ignored these crucial steps in preparing plates for intaglio printing? Or did he know that he would print with

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Using the small plates for intaglio etching instead of relief etching enabled Blake to condense his texts, averaging 59.5 lines per plate for The Book of Ahania and 58.6 for The Book of Los, versus 30.4 for Urizen, and thus use far fewer copper plates. Using two of the quarters initially prepared for single intaglio designs (as is indicated by the four original rounded corners per quarter) from this sheet for illuminated plates appears to have been an afterthought, perhaps reflecting a decision to enlarge the designs originally intended for the quarters in another medium. Blake’s decision to etch the small plates in intaglio rather than in relief appears to reflect the influence of another quarter from the sheet, Albion rose. But before we can examine how those three quarters as used connect with one another, we need to understand the role played by small Pity, the quarter that appears to have been the first executed.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

IV. Small Pity

For small Pity to have been printed from a quarter of a large copper sheet means, of course, that its matrix is copper and not millboard, but neither is it a “completely bare plate”. (Butlin, “Physicality” 4). The evidence that small Pity is from a metal plate lies also in the faintly embossed lines in the horses’ hind legs, tail, and front leg, and at the head of the supine figure (visible in the verso), the very slight embossment of the relief plateau. Knowing that small Pity is from a copper plate in slight relief and not completely bare helps to explain an apparent anomaly in the sequencing of the large color prints and to verify Butlin’s initial intuition regarding their evolution.

Butlin initially believed that Pity was Blake’s first large color-printed drawing, because it “developed from the small trial print, the only such try-out that is known, and this in turn was preceded by two composition sketches . . . the first of which is an upright composition, showing that at this stage Blake had begin page 73 | ↑ back to top not yet evolved the format for the series of large prints.” In these works (sketches, trial proof, finished impression), “one does seem to see Blake developing a completely new composition in a relatively short time from upright drawing to large horizontal color print in a way that suggests a direct evolution rather than the reuse of earlier material as found in others of the prints, and hence the real point of origin for the series.” And yet, if so, why is small Pity, “the . . . trial print,” followed by God Judging Adam, the first color-printed drawing, and not Pity? This Butlin cannot answer: “Whether this origin, in a totally new design, has any significance for the meaning of the series as a whole I leave for others to speculate” (“Physicality” 5).

Treating small Pity as a sketch that immediately preceded the larger Pity is logical, especially if you think that it too is from a “bare plate.” On the other hand, placing the trial proof after the first color-printed drawing makes no sense, especially if it is the “real point of origin for the series,” for it then becomes a “try-out” for Pity alone and not the “experiment” in color printing “on a larger scale” that Butlin also assumes (cat. 313). The material evidence, however, indicates that both the experimental small Pity and the first color-printed drawing are from copper plates, each etched in very slight to low relief, the former leading technically and materially to the latter. Indeed, small Pity is the “experiment” and “origin” that Butlin assumes. The mystery, however, lies not in Blake’s following small Pity with a “totally new design” (many sketches are not fully realized until much later), or moving from “bare plate” to relief outline to bare plates or millboards (that progression is an illusion), but rather in his following small Pity’s failure at defining form through blocks of color with a return to reliefetched outline, as used in illuminated books, before figuring out true planographic printing. As an experiment, small Pity is specifically about working out how best to define forms in large color prints, which is to say, less about format and composition than technique and style.

True, small Pity differs in format and design from everything color printed to that point; it is horizontal and a tryout for prints four times its size. It borrows from earlier works, though, even while attempting new things. Small Pity is divided into top and bottom halves that were inked in different colors (illus. 10). This in itself was not unusual, since two inks, as in sky and ground, were commonly used in color printing aquatint landscapes. Moreover, in 1794 Blake had color printed Urizen in this style, with page designs divided into texts and vignettes and inked in different colors. For example, he inked the bottom half (text) of plate 19 from Urizen copy C (illus. 38) in an olive green and the top half (figures) in yellow ochre; one can see that his dabber inked the figures’ outlines and touched down in their shallows, creating a wide white line along the base of the outline, indicating that he inked shallows and outlines together and that the relief was slightly higher here than in God Judging Adam. He went over the background in an olive green ink or color, defining the yellow ochre figures as negative spaces, or cavities within the ground. Plate 23 demonstrates more clearly this style of defining form (illus. 39).

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Small Pity uses this style to define form on a larger scale. Instead of bold outlines to delineate figures, it uses blocks of colors, leaving the forms as white or negative space to be finished in pen and ink and watercolors (illus. 41). In other words, production is divided into two stages, each stage producing a different visual effect: in the print stage, forms are blocked out in thick, mottled colors printed from the relief surface; in the finishing stage, forms left unprinted are washed in and defined in pen and ink. Small Pity fails as a technical experiment because too much is left unprinted—nearly 50% of the composition—leaving too much for finishing, resulting in white areas whose flat, thin watercolors contrast poorly with thick, mottled, alla prima paint surfaces. The combination of water-colors over or adjacent to thick colors in the smaller illuminated plates works well, but here, on the larger surface plane, the allocation of the different media to different areas makes the surface visually incoherent.17↤ 17. Perhaps Blake’s painting the horse’s rump sky blue was sign enough that the forms were poorly defined. He could have fixed the mistake by going over the blue in darker colors, but he chose to leave the impression unfinished, probably because even dark washes over a relatively large space would have appeared flat next to the thick, mottled paint printed from the plate. In short, small Pity printed but left uncolored is incomplete in ways that are not true of illuminated plates, etchings, or color-printed drawings.

Large color-printed drawings require finishing in pen and ink and watercolors (particularly in second impressions), often to keep the images from looking like blots and blurs, but it is just that, finishing; printing and coloring are not separate stages, but are instead integrated in the initial execution of the design in paint on the plate. Form is defined through line and begin page 75 | ↑ back to top colors together on the plate and then clarified, strengthened, and/or adorned further on the paper. The design on the matrix, in other words, already closely resembles the painting it will become rather than the basis for one. Matrix as organically unfolding painting would have described God Judging Adam (though of course not if its outline were printed separately from its colors), and most evidently the millboard designs that followed. As a design, small Pity could not be realized or completed without an inordinate amount of additional work that went far beyond the usual finishing, which is presumably why Blake left it unfinished, realizing that constructing designs out of printing and painting produced aesthetically inchoate textures and was not analogous to producing illuminated prints, where watercolor washes supplemented autonomous designs instead of completing them. His experiment was moving him in the opposite direction from the large painterly compositions he was envisioning.18↤ 18. In the Tate’s version of Lamech and His Two Wives, “virtually the whole image has been printed, with no reserves of paper left for finishing in watercolour.” This “seems to be a considerably more developed form of the technique” than used in Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah, “which argues that this print [Lamech] was made late in the series” (McManus and Townsend 96). In Naomi, God Judging Adam, and other prints, Blake left the figures or parts of them unprinted/unpainted to use the white of the paper, often in conjunction with white pigments, for highlights and contrast, but these are small areas relative to the composition and do not produce visually discordant surface textures.

V. Albion rose and the Book[s] of Designs

Butlin believes that Albion rose also influenced the large color-printed drawings, and again he is right, but not entirely as he supposes. Albion rose is one of two etchings and 30 illuminated plates with masked-out texts color printed on papers of two different sizes for Ozias Humphry. Blake refers to the impressions only as “a selection from the different Books of such as could be Printed without the Writing” (Erdman, Complete Poetry 771); we refer to them as the Small Book of Designs and the Large Book of Designs.19↤ 19. The Small Book consisted of 23 impressions pulled from Urizen, Marriage, Thel, and Visions, on Whatman 1794 paper 26 × 19 cm.; the Large Book consisted of plates from Urizen, Visions, separate relief plates of America plate d and Joseph of Arimathea Preaching, and two etchings, Albion rose and The Accusers, on Whatman 1794 paper cut to 34.5 × 24.5 cm. Humphry, a renowned miniaturist, appears to have already owned color-printed Songs copy H and Europe copy D as well as monochrome America copy H, which may explain why plates from these books were not in the Book[s] of Designs, despite the obvious suitability of America and Europe designs for such a project. For more information about the Book[s] of Designs and their connection to the large color-printed drawings, see Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book 302-04. Albion rose, from the latter, was color printed from the surface, with its incised lines not printed but used as guidelines for painting. In the catalogue, Butlin dates copies A of Small Book and Large Book 1794 because the date on Urizen plate 1 in the former was left as printed, “1794.” He dates copies B of both Book[s] 1796 because the printed date was altered in pen to “1796” (cat. 260). Bindman does the same and believes the two copies of Small Book represent different projects and motives years apart, with copy A serving as a “sampler of his best designs” to “demonstrate his colour-printing process,” and copy B possibly “some kind of emblem book [compiled] out of a selection of his designs” (476). Most of the B impressions, however, are second pulls, impressions pulled from the plate while ink and colors were still wet, which means they cannot be years apart. Butlin recognizes this fact in a later article (“Physicality” 3), but uses the unaltered 1794 date on the Urizen title plate in copy A for both sets of impressions. Thus, he considers 1794 as the date when “the illustrations literally broke free” of the accompanying texts. He also notes that Large Book included three subjects “based on independent engravings; the distinction between books and independent works was beginning to break down” (3). But a printed date does not date a printing session, as nearly any reprinted illuminated book demonstrates. The altered date of 1796 is more trustworthy than the printed “1794” because it bears Blake’s autograph (a similarly penned-in date of “1790” on plate 3 of Marriage copy F proved reliable); even if treated like the “1795” written on color prints produced c. 1804, it would signify the conception of the series and not the individual parts. Moreover, a project such as this one, where a selection of plates was reprinted without text, would have been an anomaly in 1794, because Blake was just beginning to reprint books and had not yet color printed from the surface of intaglio plates.

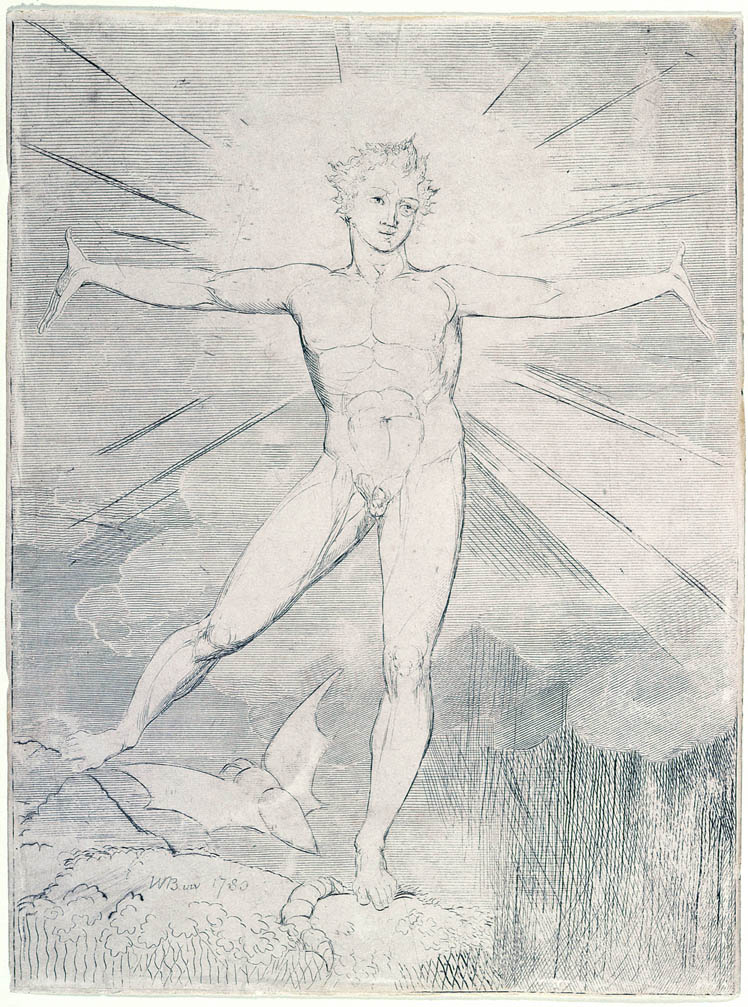

Neither color-printed impression of Albion rose could have been printed in 1794, since the plate appears not to have been cut from its sheet until 1795, along with the plates for small Pity, The Book of Los, and The Book of Ahania. Both color-printed impressions are in the first state and “were very probably produced in 1795-1796 when Blake seems to have done most of his work in that medium” (Essick, Separate Plates 28). No monochrome impression of the first state is extant. On the basis of the similarity in style to The Accusers (1793) and The Gates of Paradise (1793), Essick dates the first state of Albion rose c. 1793 (Separate Plates 28). This date can now be changed to 1795 and may explain why no monochrome impressions in the first state are extant: Blake color printed the plate before printing it in intaglio (though he probably proofed the plate during its progress and the proofs, like most proofs, are not extant). On the basis of textual and graphic evidence, Essick dates the second state of the plate (illus. 42a) no earlier than c. 1804 and possibly later than c. 1818. Albion, mentioned in the inscription, does not appear as a person in “Blake’s poetry until some of the later revisions of The Four Zoas manuscript, probably made after 1800, and in Milton, begun about 1803” (Separate Plates 28). Moreover, the inscription has a left-pointing serif on the letter g, which, according to Erdman’s hypothesis, Blake used consistently between c. 1791 and 1803.20↤ 20. See David V. Erdman, “Dating Blake’s Script: The ‘g’ Hypothesis,” Blake 3.1 (1969): 8-13. The inscription reads: “Albion rose from where he labourd at the Mill with Slaves / Giving himself for the Nations he danc’d the dance of Eternal Death.” Essick notes that the imagery in the inscription echoes that used in a letter to William Hayley, 23 October 1804, in which he likens himself to “a slave bound in a mill among beasts and devils” who has been “again enlightened with the light [he] enjoyed in [his] youth” (Separate Plates 28). The inscription reveals Blake returning to an earlier image and reinterpreting it (or remembering it as an idealized self-portrait), as he did with Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion (1773, c. 1810-20), The Accusers (1793, c. 1805-10), and Mirth (c. 1816-20, 1820-27). However, begin page 76 | ↑ back to top visual effects such as the burnished halo behind Albion’s head Essick associates with the influence of Linnell, leading him to suggest a possible post-1818 date as well (private correspondence).

Yet something is not quite right here. Because the etched lines are visible in the second, lighter color-printed impression when examined in strong light, Essick could ascertain that the first state “lacked the bat-winged moth, worm, and shafts of light radiating from the figure .... The horizontal hatching lines of the background seem to have extended much closer to the head and shoulders of the figure . . .” (Separate Plates 24). He also notes that Blake added a hill under the figure’s right foot without deleting the horizontal background lines, as he did when he added the moth. While the inscription may be c. 1804 or later, these design changes—halo, shafts of light, and hill—are likely to have been c. 1795, because they follow the color print’s coloring so closely, as is demonstrated by placing a transparency of the color print over the second state (illus. 42b). Blake appears to have used the color print as a model for the changes he made in the plate, but he is unlikely to have waited nine or more years to make these changes. The copy A impression was in Humphry’s possession by 1796 and the copy B impression appears to have been “one of the prints by Blake acquired in August 1797 by Dr. James Curry, a friend of Humphry’s” (Essick, Separate Plates 25; see also Bentley, “Dr. James Curry as a Patron of Blake,” Notes and Queries 27 [1980]: 71-73). Also, Blake seems to have used scrapers and burnishers conventionally, to erase lines and smooth surfaces so he could etch new forms, like the moth, and not radically, as he did in the second states of Mirth, Job, and Ezekiel, where he created dramatic and painterly visual effects that do indeed appear to reflect the influence of Linnell.21↤ 21. For Blake’s radical use of burnishers to create stark contrasts of blacks and whites and its association with Linnell, see Essick, Printmaker, chapters 13 and 16, and Essick, “John Linnell.” The technique’s use in Albion rose, however, seems more practical than painterly, and the resulting play of light less dramatic than in those others revised late in life.

Moreover, the worm, whose significance may be explained by a passage in Jerusalem 55:36-37 (Essick, Separate Plates 29), is visually similar to the worms in Gates of Paradise (1793) plates 1 and 18 and in The Song of Los plate 3. More interestingly, the bat-winged moth in the second state (illus. 42a) may have been influenced by the bat-winged moth in The Song of Los plates 3-4 (illus. 43). This image has heretofore been unrecorded because it appears in the middle of the horizontal plate and was masked out during printing; it is digitally recreated from traces in the plate 3 impression of copy E and plate 4 of copy B. The first state of Albion rose has always been thought to precede The Song of Los, but knowing that both works are from 1795 requires rethinking their sequence. If the second state of Albion rose was influenced by The Song of Los’s moth, then the first state of Albion rose was executed before The Song of Los text plates, which in turn suggests that the plates cut from the same sheet as Albion rose—including those for The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania—also precede The Song of Los. This sequence for the books agrees with other, stronger evidence given below.

Blake appears to have color printed Albion rose before printing it in intaglio. More importantly, it is the first intaglio plate he color printed. Misdating Large Book, with its two etchings, 1794 instead of 1796 has obscured this likelihood and its significance. Blake color printed only two other etchings, The Accusers and Lucifer and the Pope in Hell, and appears to have done so after Albion rose. The first state of the former is dated 5 June 1793; the two color-printed impressions extant are in the second state (Essick, Separate Plates 31) and were part of the Large Book, which Blake appears to have put together in 1796 by commission. No monochrome impressions of the second state are extant, which suggests that the color printing of The Accusers for Large Book may have provided the opportunity to make changes in the plate. Lucifer exists in a touched proof, with lots of pencil work in the first state and a monochrome impression in the second state.22↤ 22. The recently rediscovered proof is in the Essick Collection; it was unknown at the time Essick wrote his Separate Plates catalogue, which lists only one state for the plate (41-42). The one color-printed impression is presumably in the second state (the colors are too thick to see through and the image is pasted down on a thick sheet of paper). Essick dates the plate c. 1794 because it seems to share themes and motifs with Europe (1794), but he also recognizes that it differs stylistically from the other political prints, Albion rose and The Accusers, in that, while executed in their energetic etched

style, it makes “more use of enlarged versions of such conventional patterns as worm lines and cross hatching, much as in the Night Thoughts plates of 1796-1797” (Separate Plates 43). I agree and think Lucifer is c. 1796 and probably color printed that year, along with the other works for the Large Book and Small Book, though it was not part of either series, no doubt excluded for having a horizontal rather than vertical format.In 1796, Blake appears to have built a series of color prints around Albion rose, taking stock of his etchings and relief etchings and transforming 30 of them into miniature paintings to make up the two series for Humphry. Twenty-two years later, in a 9 June 1818 letter to Dawson Turner, he remembered the project this way:

Those I Printed for Mr Humphry are a selection from the different Books of such as could be Printed without the Writing tho to the Loss of some of the best things[.] For they when Printed perfect accompany Poetical Personifications & Acts without which Poems they never could have been Executed[.]

He then describes the color-printed drawings as:

12 Large Prints Size of Each about 2 feet by 1 & 1/2 Historical & Poetical Printed in Colours[.] . . . These last 12 Prints are unaccompanied by any writing[.] (Erdman, Complete Poetry 771)

For Blake, the illuminated plates “Printed without the Writing” and the large color prints “unaccompanied by any writing” are clearly related projects. They are also, as Blake tells Turner, “sufficient to have gained me great reputation as an Artist which was the chief thing Intended.” Butlin recognizes that the projects are connected and has done more to champion their importance to Blake’s reputation as an artist than any other Blake scholar. He has argued, though, that the small works evolved into the larger works and thus, as noted, considers 1794 as the start of Blake’s illustrations breaking free of text (“Physicality” 3). But, as shown here, the smaller monotypes are from 1796, not 1794, and found their precedent and inspiration in the larger monotypes of 1795. And like their prototypes, the later, smaller impressions were colored “with a degree of splendour and force, as almost to resemble sketches in oil-colours . . . all of which are peculiarly remarkable for their strength and splendour of colouring.”23↤ 23. Richard Thomson’s description of the Large Book for J. T. Smith’s Nollekens and His Times, as quoted in Bentley, Blake Records 621. Indeed, the color-printed drawings, begin page 78 | ↑ back to top large and small, are to oil sketches what relief etchings are to drawings. They are prints in which Blake incorporated the tools and techniques of painting, just as in illuminated prints he used the tools and processes of drawing and writing. The prints in the Small Book and Large Book are not only “free of text,” but they differ even from the color-printed illuminated plates of 1794 by having been produced in a more overtly painterly manner, no doubt influenced by the larger prints of 1795. This painterliness in the small and large monotypes is no mere illusion, as it would be if the impressions were assembled from separately printed outline and colors.

Butlin’s premise that the large monotypes of 1795 grew out of smaller works is correct, but his choice of smaller works is partly mistaken. The candidates are the illuminated books color printed in 1794, or small Pity and Albion rose of 1795. Blake first prints in colors in 1794, printing the Experience sections of Songs copies F, G, H, T, and B, C, D, and E (the two sets in that order); Europe copies B, C, D, E, F, and G; The Book of Urizen copies A, C, D, E, F, and J; and possibly Visions of the Daughters of Albion copies F and R and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell copies E and F. He color printed The Book of Los, The Book of Ahania, and The Song of Los in 1795. The last of these, as we shall see, is likely to have been executed concurrently with or after the large color-printed drawings and under the influence of their format and technique, whereas the first two books are etchings that appear to have been executed before the color-printed drawings but after Albion rose, as indicated by Blake’s change of mind regarding the original quarter sheets used to provide their plates. Many significant differences exist between color printing relief etchings and intaglio etchings. With the former, Blake is inking plates as prints and adding colors to inked and uninked areas. He behaved even more radically with the latter works. Blake is not inking the plate; he is painting it, using etched lines as guidelines, but he is also free to improvise at will, as he did with hill and halo in Albion rose. Nothing like these had ever been produced before and no analogous printing process exists.

Recognizing Albion rose as a product of 1795 rather than 1794, as the first color-printed intaglio plate, and as cut from the same sheet as small Pity helps us to see it and small Pity more clearly as experiments in color printing that reveal the technical problem Blake is attempting to solve. He, as intaglio etcher and relief etcher, quarters a large sheet of copper and prepares three plates for intaglio and one for relief. He uses the relief etching to experiment with creating a matrix capable of being color printed as a relatively large composition. He needs to scale up in size his earlier experiments; to date, he has color printed from both the surface and from the surface and shallows simultaneously of relief etchings. He needs to figure out how to define forms on larger surfaces in the new marriage of print and painting that he was then envisioning. Were forms to be blocked out in low flat relief, as in small Pity, in relief outline, as in illuminated plates, or in incised outline, as in Albion rose? Albion rose can be printed without colors or finishing, but small Pity cannot; the latter work was designed with color printing in mind while the former probably was not. As Blake was beginning to experiment with scaling up his color prints, however, he put Albion rose to double use, testing its suitability for large printed paintings by painting the design and printing it. The idea to color print Albion rose from its surface instead of printing it as an etching may have occurred to Blake during its execution or after recognizing the failure of small Pity.

The basic principle, one could argue, for inventing large monotypes is present in color printing relief etchings, but, in practice, Blake is closer to working up flat areas and defining forms through colors when color printing intaglio etchings. Does this mean Albion rose was more influential in what followed than small Pity? Yes and no. The intaglio etching appears directly to have influenced the choice of medium and color printing technique of The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los—works one quarter the size of Albion rose—but not the color-printed drawings, which are four times its size. Interesting, in this regard, is Blake’s never having color printed the intaglio engravings that are the size of the color prints, like Job and Ezekiel, perhaps finding the dense line systems unsuited for the open and painterly compositions he was then creating—or because such surfaces proved more difficult to use than gesso’s striated surfaces. In any event, he apparently decided not to use etched outlines for his large printed paintings, following small Pity with God Judging Adam. What, then, leads to true planographic printing, which lies, technically speaking, somewhere between small Pity and Albion rose?

Blake possibly went from small Pity to God Judging Adam and returned to Albion rose to think more on the problem of defining form. The idea of a non-printable outline—neither in relief nor intaglio—but paintable along with blocks of colors could have grown out of painting and printing Albion rose. Alternatively, it could have grown out of painting over a low relief outline of God Judging Adam and realizing that the outline’s function could be served planographically, that it was the painting over the outline rather than printing the outline that mattered most. Once Blake made that discovery, returning to color print an intaglio etching or moving to the planographic printing of Elohim or Satan and then to millboards must have come quickly.

VI. The Song of Los Reconsidered

Determining the exact sequence of development in Blake’s monotyping may be impossible, because planographic printing can evolve out of painting the surface of an etching, using the incised lines as guidelines, or vice versa. However, the use of one sheet of copper to produce both small Pity and Albion rose, two plates representing different technical solutions to defining forms needed for printing large monotypes, does help us sequence the illuminated books of 1795. The size of the sheet may have influenced the size of the subsequent sheets acquired for the color prints. Recall that Blake described the “Size of Each” of his “12 Large Prints” at “about 2 feet by 1 & 1/2” (Erdman, Complete Poetry 771). Since these begin page 79 | ↑ back to top

Assuming Blake treated the sheet yielding The Song of Los plates 3-4 and 6-7 like the one for The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los, i.e., cutting it in half, then the unused half would also be approximately 43.5-8 × 27.2-5 cm. Cutting this half to provide the coppers for The Song of Los plates 2/5 and 1/8 appears logical, but to have done so would have meant wasting precious metal, because 24.2 × 17.4 cm. (2/5) and 23.6 × 17.5 cm. (1/8) do not fit without lots of awkward trimming. Moreover, plates 2/5 and 1/8 do not fit together; they were not conjoined in a sheet. Thus, while technically possible, economically it made no sense—and as his recto-verso etching demonstrates, Blake was very practical in his use of copper. He may have bought just half the sheet, intending to halve it for The Song of Los text plates, or bought the whole sheet and used the other half or pieces from it later.25↤ 25. Blake’s Child of Nature (1818), known from a unique impression, is 43.3 × 27.5 cm., the size of the half sheet. Other possible configurations include the Moore & Co. Advertisement, c. 1797-98 (Essick, Separate Plates 47), along with some practice plates for Thomas Butts (see Essick, Separate Plates 211-12). Blake reused parts of the Moore plate years later for Jerusalem plate 64, which is the recto of Jerusalem plate 96 (Essick, Separate Plates 48). However he used it, plates 2/5 and 1/8 appear certainly not to have been cut out of it, which supports the evidence below that they were not copper but millboards.

Plates 1 and 8 were planographically printed; no relief lines or marks are present in the versos of any impressions from either plate. No traces of incised lines are seen through the impression in strong light, as can be seen in the copy B impression of Albion rose. Blake either lightly etched or scratched begin page 80 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Plates 2 and 5 are also planographically printed. In plate 5 (illus. 45), figures, lily petals, and stems are consistent in each impression and carefully finished in watercolor washes and pen and ink. The broad green and brown leaves under the lilies, however, differ in number, form, and placement in each impression, signs of improvisation, of having been painted broadly and energetically directly on the plate rather than painted within an outline. Here, Blake paints each design anew, creating prints with both the miniature’s exactness of form and the freedom and boldness of the oil sketch.

Essick was first to recognize that plate 2 is the only illuminated plate with planographic lettering, though he acknowledges that the letters may have had “lightly incised” outlines (Printmaker 128). Dörrbecker agrees and adds that the letters begin page 81 | ↑ back to top

The accepted sequence of The Song of Los, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los has Blake returning to the continental myth before finishing the Urizen cycle. It pictures him creatively experimenting in The Song of Los with page format and text design and using small color-printed drawings as book illustrations, only to return in the intaglio books to the earlier text format of Urizen. We now can see that The Song of Los is last in this sequence and that Blake completed the Urizen poems first and without interruption, with two much shorter books whose planographically printed images were directly influenced by the color printing of Albion rose. The Song of Los plates 3-4 and 6-7 are horizontal compositions influenced apparently by the format of Blake’s new invention, the large begin page 82 | ↑ back to top

With The Song of Los as originally conceived, Blake returned to his continental cycle using the same relief-etched print medium but in a painting format. For whatever reason, he changed his mind and decided that his “Africa” and “Asia” needed to be reformatted. He masked one side of the horizontal plate when printing to transform texts into book pages. He executed full-page illustrations on millboard after the text plates and designed them to match in shape and size the plates of America and Europe. In doing so, he appears to have salvaged an experiment he abandoned by extending what he learned about planographic printing from millboard into book production. The fact that The Book of Los and The Book of Ahania are not to Urizen as Experience is to Innocence, but are clearly related parts differently formatted, may have freed Blake from thinking that “Asia” and “Africa” had to match America and Europe exactly. The non-symmetrical relation within the Urizen cycle may have enabled him to reconstruct The Song of Los into a book with two “continents” and fewer than half the number of pages in America or Europe.

Butlin is surely correct that “1795 can be seen as a vital year in Blake’s evolution, that in which his pictorial art finally achieved maturity with works of the highest quality while, conversely, his production of illuminated books suffered a hiatus for over ten years ....” I hope, however, in light of new information about how small Pity was designed and executed, when and how Albion rose was printed, the size of the copper sheet and manner in which it was cut to yield their plates and the plates for The Book of Ahania and The Book of Los, how the small intaglio illuminated plates were printed, how the large color prints evolved and were executed and influenced the Large and Small Book of Designs, and, mostly, how The Song of Los began as texts designed in landscape format and was recreated as a book by the masking of these plates during printing and the inclusion of small color-printed drawings, that the last illuminated books of this period can be thought of as more than “the three relatively unambitious books of 1795” (“Physicality” 6).

Works Cited

Bentley, G. E., Jr. Blake Books. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

—. Blake Records. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Bindman, David. The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

Butlin, Martin. “‘Is This a Private War or Can Anyone Join in?’: A Plea for a Broader Look at Blake’s Color-Printing Techniques.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 36.2 (fall 2002): 45-49.

—. “A Newly Discovered Watermark and a Visionary’s Way with His Dates.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 15.2 (fall 1981): 101-03.

—. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

—. “The Physicality of William Blake: The Large Color Prints of ‘1795.’” Huntington Library Quarterly 52 (1989): 1-18.