REVIEWS

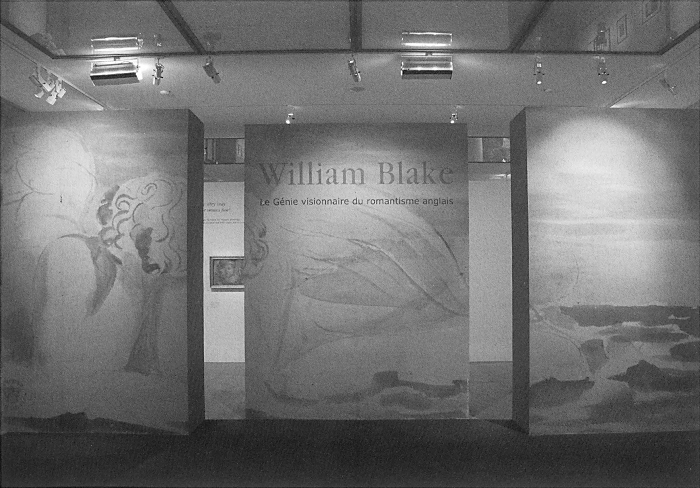

William Blake (1757-1827): The Visionary Genius of British Romanticism. Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, 2 April-28 June 2009. Guest curated by Michael Phillips with Daniel Marchesseau, Directeur du Musée de la Vie Romantique.

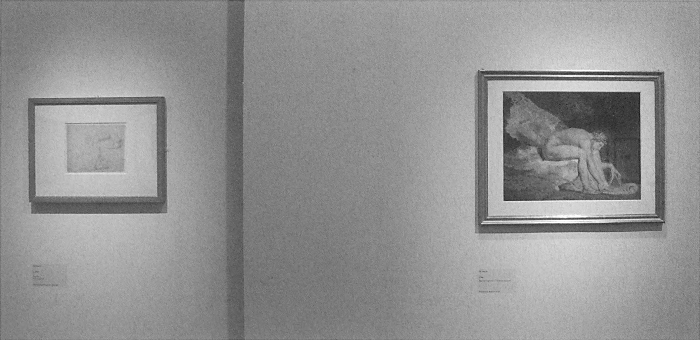

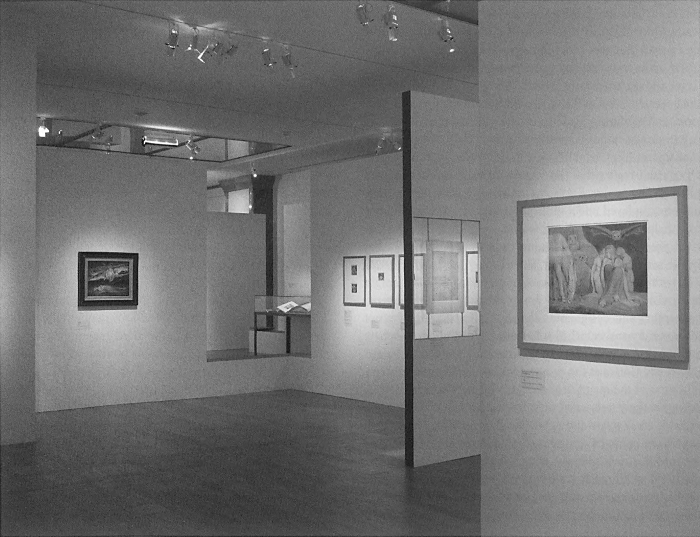

THE FIRST to appear in France since 1947, this retrospective contains over 130 of Blake’s works and, as the official web site states, “introduces William Blake as poet, painter and artist-printmaker.” The exhibition spans Blake’s career, offering work from his apprenticeship to his final engraved calling card for George Cumberland. A number of media are represented, from early pencil sketches and stipple engravings to relief etchings, illuminated prints, large color-printed drawings, and paintings. On display as well is the burnished copperplate for plate 11 of Illustrations of the Book of Job (1825 [1826]) alongside the resulting printed page, a pairing that reveals the fine marriage of metal and paper that is so difficult to visualize without the material fact of the plate itself. These two items alone are worth the price of admission, though the rarely seen color print Newton (1795) from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the vividly colored second-state engraving of the Canterbury Pilgrims (c. 1810-20) offer equal delights. The exhibit concludes with several contemporary tributes to Blake, including a lithograph of Francis Bacon’s Study after the Life Mask of William Blake (1955), Jean Cortot’s Hommage à William Blake (1985), and a clip from Jim Jarmusch’s film Dead Man (1995). Many of the original works on display are drawn from the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, though a significant number are on loan from the British Museum, the British Library, Glasgow University, Manchester Art Gallery, the Victoria University Library (Toronto), the Louvre, and several private collectors.

Anyone looking for a synopsis of the variety and breadth of Blake’s artwork would be hard pressed to find a more splendid visual introduction than the one guest curator Michael Phillips has assembled here. The great strength of this exhibit is that it succeeds admirably in making these works accessible to native French and English speakers alike—no small feat given Blake’s visual-verbal designs and his often diminutive begin page 62 | ↑ back to top

calligraphy. In its straightforward chronological organization, its clear presentation of a variety of works, and its progressive movement through the stages of a revolutionary career, the exhibition offers a magnificent introduction to Blake’s versatility and range, not to mention his evolution as an engraver and thinker. Deliberately, I think, it represents only two complete sequences of plates from, appropriately, Europe a Prophecy (1794) and the Virgil woodcuts. The rest of the works are grouped according to six periods of Blake’s life, outlined in the exhibition’s information sheet: “Blake’s Apprenticeship,” “First Visions/First Poems,” “Blake as a Copy Engraver,” “Relief Etching and Illuminated Books,” “The Large Colour Prints,” and “The Last Twenty Years.” Each section is introduced by a helpful paragraph by the curators stenciled on the walls in French and English, and each is accompanied by a famous quotation from Blake’s poetry: “How do you know but ev’ry Bird that cuts the airy way, / Is an immense world of delight, clos’d by your senses five?” “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,” etc. This is a greatest-hits album which will not fail to please the specialist as well—the sheer amplitude and quality of the work on display are staggering, and richly reward close attention.On the morning I visited (26 May), gallery traffic was light, so I was able to linger in front of the artworks and inspect details without the insistent pressure of fellow patrons to move me along. I drifted backwards through the space several times, pausing to revisit favorites like plates 8 (naked Orc) and 12 (Orc aflame) from the Fitzwilliam’s America a Prophecy, and loitering before the three large sheets from Vala that were intelligently sheathed in vertical glass sections so as to display both recto and verso. Spending time before works like these made me think about the online Blake Archive, a miracle of technology which has now become essential for classroom and conference use, but still no substitute for the original manuscripts and plates. While the screen may register an accurate palate of colors, it necessarily flattens the composition and texture of the paper, smoothing the rough geography of the page and bathing each work in a shimmering cyberglow. In the original plate 8, by contrast, I was able to spy fine flecks of gold dusting the pictured leaves and foliage, gold not apparent in the online version. I could also see more layers of applied watercolor and, lo and behold, even the wiry mesh of pubic hair sprouting luxuriantly around Orc’s exposed groin (I had always thought Blake airbrushed his heroes’ genitals!).

I had never seen the exhibited plate of “The Tyger,” an early color-printed copy which belonged to the late Sir Geoffrey Keynes and is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum. The plate is not represented among the eleven versions in the Blake Archive, and is significantly different from most copies, which features a marked contrast between the light shadings of the tree and the more brightly colored tiger. In this version the tiger is printed in the same mottled, earthy tones as the tree, its head splashed with what looks like patches of brown enamel. There are swirls of muted blue highlighting the legs and gesturing at stripes on the shoulders, but there are also hints of blue in several places on the tree, most noticeably on the branch opposite the “grasp/clasp” rhyme. The tiger’s hindquarters look like they’re growing directly out of the tree, or almost as if they have fused with it (the back right leg is nearly impossible to distinguish), a decidedly organic effect that is echoed by the bending branches that separate the stanzas. So here tree and tiger are one and the tiger is even more rooted and static than usual. While the lightly printed text reaches for the stars, the image remains brown and heavy, earthbound. The terrifying textual beast prowls “the forests of the night,” his visual counterpart fixed harmlessly below. Small discoveries begin page 63 | ↑ back to top like these make any visit to an exhibition of artworks or manuscripts worthwhile, especially to those of us weaned on print and screen facsimiles. It’s refreshing to have the chinks of the cavern briefly widened. And the great wonder of Blake is that he never stops compelling you to see, to see further, finer.

The exhibit also affords the opportunity to compare the pencil sketch of the frontispiece for The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, for example—and that not all are in the pristine state of the Newton or Joseph of Arimathea (1773). These blemishes serve to pull the works out of the airless sanctity of the museum and trammel them with time. Some will disagree, but I think it’s useful to find artworks humanized (and historicizes) in this way, brought closer to the temporal experience of the viewer.

Other highlights of the exhibition include the life mask by J. S. Deville and portraits by John Linnell and Blake’s wife, Catherine; one of only two known intaglio prints of Laocoön (c. 1826-27); several drawings and engravings based on the Book of Job; a number of Blake’s watercolor illustrations to the Bible; and selected plates from the Songs, The Book of Thel, and The Book of Urizen. An edition of John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796), for which Blake engraved the plates (here colored), is displayed open to several graphic scenes of punishment, and thoughtfully paired with the frontispiece and title page from Visions of the Daughters of Albion, which depict scenes of captivity and flight. Other sequences in the exhibition are more puzzling, however. Midway through we encounter a wall that features, from left to right: “The Chimney Sweeper” from Innocence and from Experience, “Holy Thursday,” from Innocence, “Nurses Song” from Experience, “Nurse’s Song” from Innocence, and finally “A Divine Image” from Experience. The first pairing allows us to compare the two versions and note Blake’s keen psychological awareness of point of view. “Holy Thursday,” however, lacks its companion piece, and the two plates of “Nurse’s Song” are in the wrong order. “A Divine Image” is a small but powerful statement

begin page 64 | ↑ back to top rooting man’s inhumanity in “the Human Form Divine” rather than an abstract God. But lacking its counterpunch in “The Divine Image” from Innocence, the plate loses its qualifying irony as well as additional layers of meaning. I wonder also about the decision to stack the plates from Europe one above the other in a double line, a configuration that disrupts the linear sequence of the book. For those French visitors having trouble following the work because it is a difficult narrative and written in English, this presentation will be confusing. Wouldn’t one want to adhere as closely as possible to Blake’s intended visual order and thus mimic for the viewer the actual experience of reading the book?Michael Phillips, who co-curated the major Blake exhibitions at Tate Britain and the Metropolitan Museum in 2000-01, deserves a lot of credit not only for assembling such a stunning array of artwork from so many different institutions and collections, but also for pulling it all together abroad. I suspect the negotiations were laborious and time-consuming. Difficult too must have been the logistics of organizing the details of the exhibition, from laying out the floor-plan to creating bilingual labels and publicity material. My one regret is that more of this energy wasn’t expended on the installation and on imagining the overall structure and design of the space, which is rather orthodox, moving us back and forth through a series of rectangular blocks. As we enter the gallery, the initial “confrontation” consists of three massive Stonehenge-like walls which magnify a portion of a watercolor and wash it in a pastel blue that blurs the represented form of an angel. These walls serve to thwart our entrance rather than inviting us in, and do not clearly enough direct our path. Located on the basement level of the museum, the entire space seems to small and confining, as if Blake’s work is once again contained in its volumes rather than being liberated from them. (I imagined figures like Orc and Urizen trying to jump off the walls.) Of course I realize that the fragility of these works on paper, many in watercolor, limits a curator’s options, and that they must be displayed under reduced lighting conditions. But one can’t help feeling the absence of an opening or vista, a circular passageway up or out as in the watercolor from Blake’s Dante series exhibited here, The Circle of the Lustful (1824-27), with its upswelling river of bodies. Blake himself might have wished for a bit more irreverent pizzazz in the overall conception and design. Standard labels and fonts—why not more variety and color? Blocked rectangles and lines—where are the circles and vortexes, the irresistible sweep upwards? Bacon and Cortot at the end—why not Ginsberg, the Doors?

In view of the quantity and quality of the works presented, however, these are small complaints. This is an ambitious show of great scope and power, sure to mobilize an army of new Blake converts on the continent. Even as I was leaving the exhibit something was already brewing. The gallery began to fill with French visitors murmuring excitedly about the works. Unexpectedly, a single guard began shushing them. He shushed three times, each more loudly, but to no avail. The murmurs grew to a buzz and then to a glorious din.