REVIEWS

William Blake’s Watercolour Inventions in Illustration of The Grave by Robert Blair. Edited with Essays and Commentary by Martin Butlin and an Essay on the Poem by Morton D. Paley. Lavenham, Suffolk: William Blake Trust, 2009. 186 copies printed for sale, of which 36, numbered I-XXXVI, are quarter bound in calf to accompany a replica of the original portfolio containing the 19 now-dispersed “Designs for Blair’s Grave” reproduced in facsimile and mounted like the originals. Copies numbered 1-150 for sale without the replica portfolio. 95 pp., 62 illus. £2500 for the issue with the replica portfolio containing an additional suite of reproductions; £295 for the volume alone. Distributed worldwide by John Windle, Antiquarian Bookseller, San Francisco.

William Blake. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. A Portfolio of Eighteen Facsimile Impressions. Orlando: Flying Horse Editions, University of Central Florida, 2009. With “A Note on Production” by Michael Phillips. 33 copies printed, plus 3 printer’s proofs and 1 archive copy. Accompanying paperback booklet 36 pp., 10 illus. $1950.

THESE two publications appeared within days of each other in fall 2009. Although there are many differences between them, both are elegant works, of interest to collectors of fine books as well as Blake enthusiasts, and both are major contributions to the long and fascinating history of reproducing Blake’s art. Although reviews generally focus on the verbal contents of books, while ignoring (or only mentioning in passing) their physical containers, the visual impact and even tactile nature of these publications are part of their significance.1↤ 1. In the interest of full disclosure, let me point out that the Blake Trust sent me a complimentary copy of the issue with portfolio, “O.o.s” (out of series). Flying Horse Editions sold me copy no. 1 at a reduced, pre-publication price. I had a minor role in assisting the Blake Trust acquire digital files for its publication; I have had e-mail correspondence with Theo Lotz, director of Flying Horse Editions, and Michael Phillips about their publication.

The William Blake Trust has a distinguished record as the last century’s foremost publisher of reproductions of Blake’s works. In association with the Trianon Press, the trust produced a series of color facsimiles of the illuminated books, beginning with Jerusalem in 1951 and concluding with The Book of Los in 1976. These limited editions, generally bound in quarter leather over marbled boards, were produced through a combination of collotype and hand coloring through stencils. The trust concluded its efforts using these processes in 1987 with the publication of Blake’s various illustrations of the Book of Job. In the 1990s, the trust shifted its focus toward a more affordable series of six volumes featuring more extensive scholarly apparatus and commercially produced, but high-quality, color reproductions. The trust’s latest publication, reproducing Blake’s watercolor illustrations for Blair’s Grave, combines the limited-edition features (and prices) of its first series with the commercial reproductions of the second—but based on digital files rather than color transparencies. Sophisticated ink-jet technology was employed in printing the illustrations.

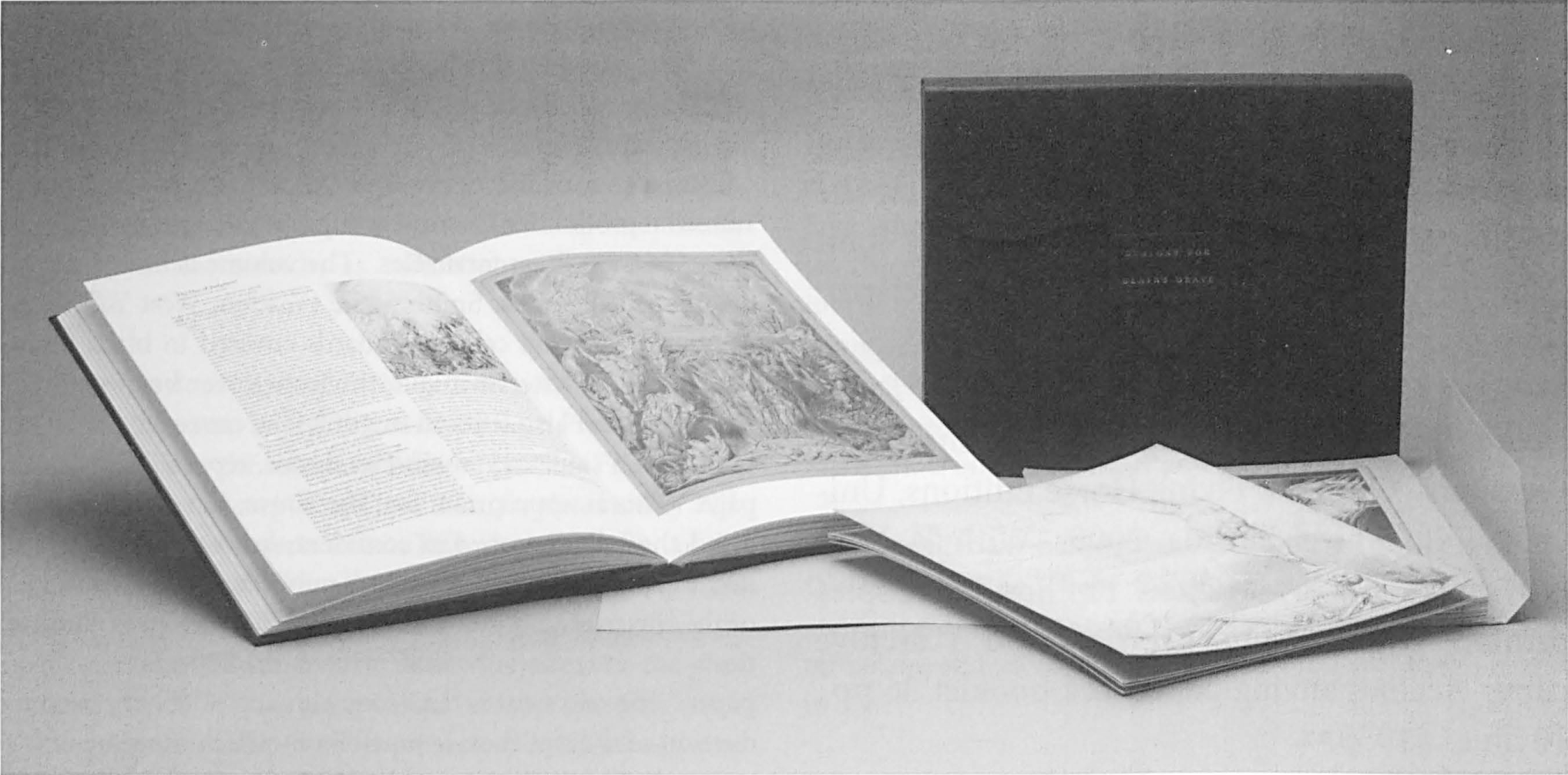

The edition of the Grave watercolors with the additional suite of reproductions is more sumptuous than even the Blake Trust/Trianon Press facsimiles. The volume is bound by the distinguished firm of Smith Settle (Yeadon, West Yorkshire) in quarter maroon calf over boards covered in black moiré silk, the spine lettered in gilt, the front cover bearing a maroon calf label also lettered in gilt.2↤ 2. I have not seen the issue without the additional suite of illustrations in portfolio, but the prospectus indicates that the volume is bound in silk without the quarter calf. The cover label is decorated with a skull and crossbones device, repeated on the title page. This is appropriate for The Grave, but also brings to mind the Jolly Roger. I’m confident, however, that there is nothing piratical about the trust’s publication. The top edges of the leaves, 37.2 × 27.0 cm., are gilt. The text and illustrations are exceptionally well printed on 200-gram archival paper. The real treat is the accompanying portfolio, a reproduction of the wallet-style portfolio in which nineteen of the watercolors were discovered in 2001 after an absence of 165 years. The original was offered as the last lot in the auction of the watercolors at Sotheby’s New York, 2 May 2006. It was knocked down to John Windle, the San Francisco book dealer who is also the distributor of the Blake Trust Grave, for $4,200 and is now in a California private collection. The main differences between the original portfolio and the re-creation are the inclusion of an inner paper folder (complete with cover label) to enclose the mounted plates, a pull ribbon, the use of calf rather than morocco, and the lack of wear on the new portfolio (I am tempted to do a bit of antiquing). The volume and the portfolio are housed together in a black moiré silk slipcase. Depending on one’s tastes, this is either an overly begin page 104 | ↑ back to top rich soufflé or the sort of splendid treatment Blake’s works deserve. I am of the latter opinion, for the packaging does not overwhelm the contents.

As John Commander, executive director of the Blake Trust, explains in a brief foreword, the raison d’être of the publication is the full-color reproduction of the Grave watercolors, now widely dispersed in private and institutional collections. To the group of nineteen recently rediscovered drawings is added Prone on the Lowly Grave—She Drops, sometimes titled The Widow Embracing Her Husband’s Grave. Now in the Yale Center for British Art, this watercolor is on the same type of mount as the others and must have once been part of the set of “20” which Robert Hartley Cromek, who commissioned Blake’s designs for an illustrated edition of Blair’s poem, “proposes [to] have engraved.”3↤ 3. John Flaxman’s letter to William Hayley of 18 Oct. 1805, quoted in G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) [hereafter BR(2)] 207. This main sequence, reproduced

in color “at approximately 98% of the originals’ size” (29), includes the framing lines on nineteen of the mounts to which the watercolors are affixed and is supplemented by twenty-nine illustrations, mostly in color, of related works. The volume also includes a reproduction on a reduced scale of the text of Cromek’s 1808 edition of The Grave, followed by almost full-size reproductions of Blake’s twelve illustrations etched and engraved by Louis Schiavonetti, plus the frontispiece portrait of Blake (Schiavonetti after Thomas Phillips). The plates are in the second published state appearing in the quarto issue of the 1808 edition. The additional suite of reproductions appropriately includes only the nineteen watercolors found in the original portfolio, each mounted like the originals on thick card. The title-page design extends to the edges of its backing mat; the mounts for all the other designs are, like the originals, inscribed with framing lines. When I first saw the newly discovered Grave watercolors in London in 2002, they were spread out on a large table. The Blake Trust portfolio permits repeat performances of that amazing sight.The reproductions of the twenty Grave watercolors are excellent. Based on high-resolution digital files, the illustrations lend an almost relief appearance to Blake’s fine pen and ink outlining. I suspect, however, that the paper in the title-page design, Friendship, and Prone on the Lowly Grave has shifted to a hue slightly browner than the originals. Capturing paper tone is always very difficult; getting it right often results in misrepresenting some other colors. A more significant problem in my copy is that three of the reproductions in the bound volume (but not in the portfolio) have been trimmed along one or more of their margins. The toes on the right foot of the descending trumpeter have been cut off at the top margin of the title page. In The Meeting of a Family in Heaven, the foot of the hovering angel on the left, most of the left foot of the angel on the right, and most of the right foot of the boy lower right have been amputated. The top of the head of the fleeing soul in Death of the Strong Wicked Man has been lowered. As noted, the original title page is mounted to the edge of its backing, but all the other reproductions in the volume include the ruled lines on the backing mounts as part of a single image, and thus these trimmings of the watercolors within the ruled lines are difficult to explain. Windle, the distributor of the work, has told me that these faults, having been identified in a preliminary run of copies not for sale, were rectified and are not present in regularly numbered copies. Other, less significant, differences between the reproductions in the bound volume and in the portfolio, such as the darkness of the foxing evident in the originals, teach us once again that no two reproductions of the same object are ever identical, even within the same publication.

begin page 105 | ↑ back to topI have compared the images in the Blake Trust volume to two of the originals, The Death of the Good Old Man and Heaven’s Portals Wide Expand to Let Him In, both in my collection. It is very difficult to tell them apart. If I were truly conservation-minded I would take the originals off the wall and replace them with the reproductions. Nobody would notice. I have also been able to compare one of the supplementary illustrations, Blake’s white-line etching of “Deaths Door,” to the unique impression of the original. The reproduction is a bit darker and obscures the rolled mat or bedding within the tomb, but the velvety texture of its black ink makes it look like another—and better?—impression from Blake’s copperplate on much the same paper as the original, time-darkened to a light tan. Should you see a second “original” impression of “Deaths Door” on the market, be suspicious that it is the Blake Trust reproduction cut out of the book.

Blake scholars are now in the fortunate position of having three complete color reproductions of the Grave watercolors: Sotheby’s 2 May 2006 auction catalogue, the online William Blake Archive <http://www.blakearchive.org>, edited by Morris Eaves, Joseph Viscomi, and this reviewer, and the Blake Trust publication. The last two add Prone on the Lowly Grave to the nineteen offered by Sotheby’s; the archive illustrations do not include the framing lines on the backing mats. The archive arranges the designs according to the sequence of the passages illustrated, with those not based on any specific passage grouped at the end. The Blake Trust sequences the designs published in 1808 according to their order in that work, followed by the unpublished designs. Sotheby’s arranged its lots so that the most valuable objects would fall in the middle of the sale—apparently in a failed attempt to maximize prices (the drawings with the highest estimates did not sell). The reproductions are exceptionally good for an auction catalogue, but have the most color shifts. The archive images were made from the same color transparencies used by the auction house, but corrected according to notes Joe Viscomi made in his copy of the catalogue while comparing its reproductions to the originals. Because the archive images are backlit on a monitor, the colors tend to be more saturated, and hence the paper and paler washes lighter, than either the originals or the Blake Trust illustrations. This inevitable distortion highlights certain very thin washes, such as the yellows and reds in The Reunion of the Soul and the Body. The archive images also reveal a good deal more of the foxing and staining on the watercolors, particularly on The Meeting of a Family in Heaven. I wonder if some of the Blake Trust digital files were cleaned up a bit in Adobe Photoshop. The 300dpi enlargements available in the archive are unsurpassed for the study of details, the closest approach to viewing the originals with a powerful magnifying glass. The Blake Trust illustrations are not suitable for similar levels of magnification because they will dissolve into a dot-matrix pattern, the paper-print equivalent of pixelation in a digital image. Each reproductive technology has its own virtues and its own limitations.

The dazzling pictorial contents of the volume should not be allowed to hinder attention to the accompanying texts.4↤ 4. A few typos crept into the text, including “reseaches” (for “researches”) in the “Editor’s Acknowledgements” (7). Would it be mere pedantry for me to suggest that the second “of” in the title Songs of Innocence and of Experience should not be omitted, as it is on page 58? Morton Paley’s brief essay, “William Blake and Robert Blair’s The Grave,” builds fruitfully on his 1982 coauthored book.5↤ 5. Essick and Paley, Robert Blair’s The Grave Illustrated by William Blake: A Study with Facsimile (London: Scolar Press, 1982). He offers some new information about Philip Doddridge’s involvement in the composition and publication of Blair’s poem. Paley also proposes that Blake “sympathized with the evangelicism of the poem” (10) and suggests that we consider Blake’s responses to it within the context of his “conversionary experiences during the years 1801-03” (11) and the impact of those experiences on Milton and Jerusalem. The white-line etching of “Deaths Door” is singled out as expressing a sense of “inner rebirth” and an “almost primitive sense of death and resurrection” (11), but what other designs can be related to Blake’s religious beliefs? The essay ends abruptly, leaving me wanting more, much more, about this fascinating thesis.

Martin Butlin’s contributions, set forth with his usual clarity and precision, are divided into three sections, “The History of Blake’s Illustrations to The Grave,” “The Newly Discovered Watercolours,” and “The Watercolours: Catalogue and Commentary.” A good deal has been written, both before and after the discoveries of 2001, about Blake’s Grave project and his relationship with Cromek; Butlin necessarily covers much of this material, particularly when factual in nature.6↤ 6. See particularly BR(2) and the Essick and Paley volume. Most of the basic facts about the watercolors were previously published in Butlin, “New Risen from the Grave: Nineteen Unknown Watercolors by William Blake,” Blake 35.3 (winter 2001-02): 68-73, and in the 2 May 2006 Sotheby’s auction catalogue. There is, however, some new information and well-informed speculation, some of which might easily go unnoticed. For example, I believe that this is the first recording of some of the watermarks: EDMEADS & PINE in several of the watercolors, JWHATMAN / 1800 on one mount, JWHATMAN without a date on two mounts, and JRUSE / 1800 on one mount (21). I was also interested to learn that the “full-page design [for the Grave title page] is mounted on the same card as the rest of the newly discovered watercolours” (30).

The watermarks and some of Butlin’s other perceptions about the backing mounts open up interesting possibilities. He comments that “the fact that all of the watercolours are treated in the same way suggests that this must have happened before Blake, or Cromek, knew that the number of engravings was going to be cut down from the original twenty” (21). This is not necessarily the case. The suite of watercolors, executed in fall 1805, may have been assembled and mounted in the next year as a unique collection for sale independent of the 1808 book. The final break between illustrator and publisher did not occur until May 1807, when Cromek refused Blake’s begin page 106 | ↑ back to top dedicatory design “To the Queen.” At least some involvement with the mounts on Blake’s part is possible. Prone on the Lowly Grave is inscribed on the mount below the drawing “W. Blake. del” and three lines are quoted from the poem. I believe that Butlin may be right when he states that these inscriptions “would indeed appear to have been done by Blake himself” (68). Did Blake also produce the mounts himself, including the framing lines in the so-called “French” style, possibly at Cromek’s request? The watermarks, two of which include a date of 1800, show that the mounts were made with papers familiar to Blake, for he used Whatman and Ruse & Turners papers for many of his illuminated books and drawings. By no later than 1821, Blake began to inscribe framing lines around the prints in some of his illuminated books. Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy V, available in the Blake Archive, is a representative example.7↤ 7. Copy designations for the illuminated books follow G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977). Blake has drawn, as with the Grave watercolor mounts, three framing lines (not counting an outline contiguous with the edges of the image) on each page and added pale color washes between two of the lines. Even if Blake did not personally mat and inscribe the frames for the Grave watercolors, their treatment may have prompted his own later practices.

Some of Butlin’s most interesting observations concern drawings related to Blake’s Grave commission. A Destroying Deity, a watercolor in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, can be associated in size and format with The Grave Personified as its “negative counterpart” (54). This relationship continues the pairing of contrary companions found throughout Blake’s Grave designs. As Butlin points out, the male figure in A Destroying Deity may actually be a personification of Sin, as described on pages 26-27 of the 1808 Grave. He does not take the final step of changing the title of this drawing to Sin Personified, perhaps because Sin (as in Paradise Lost) is “described as female” on page 27.

Butlin tentatively proposes the deattribution of two drawings. He suspects that “the drawing apparently from the Butts collection” of an ascending trumpeter (Yale Center for British Art), associated with the descending angel in the Grave title-page design, “is perhaps not by Blake” (30), and that Death Pursuing the Soul through the Avenues of Life (Essick collection) “is perhaps a pencil drawing gone over by someone else to make it more saleable in the later 19th century” (24). Might the trumpeter be wholly or in part the work of Thomas Butts, father or son, when the latter was learning etching from Blake, c. 1806-08? When sold at Sotheby’s, 22 March 1910, the drawing was grouped in lot 447 with “a number of engravings and drawings, by William Blake and some by T. Butts, his patron ....” I will pursue the attribution of Death Pursuing in a separate essay; the Yale Center may have more to say about its drawing.

The title-page design also suffers a partial deattribution: “It is difficult to believe that Blake himself could have written out the title [on the title-page watercolor] crediting the engravings to Schiavonetti; one can only assume that the lettering was done either by Schiavonetti himself or by Cromek or one of his assistants” (30). As Butlin points out, “Blake seems to have remained on relatively good terms with Cromek well into 1807” (16), and thus well past the time when Blake must have known that he had been replaced by Schiavonetti as the engraver.8↤ 8. The second prospectus names Schiavonetti as the engraver and is dated, like the first, “Nov. 1805” (see Bentley, BR(2) 210-12, 214-15 for reproductions of both prospectuses). Cromek must have delivered Blake’s watercolors to Schiavonetti by late 1805 or very early in 1806, for a proof of Schiavonetti’s “Death’s Door” plate, with the design completed, is dated “Feby 1st 1806” in the imprint. The hand that inscribed the title page also inscribed the watercolor of an alternative title page for “A Series of Designs: Illustrative of The Grave” (Huntington Library); both include an “1806” date. The pen and ink used for the inscriptions appear to me to be the same used to outline many motifs in the designs of both drawings; the lettering shows the same elegance as Blake’s so-called “copperplate” hand in the Four Zoas manuscript. The unusual formation of the lower-case “g” with serif, particularly in the first line of the inscription on the Huntington drawing, and the addition of a serif to the lowercase “s” in the same line, recall Blake’s calligraphy in the illuminated books (for example, plate 3 in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell). Butlin may be right, but I have only slight difficulty in believing that “Blake himself could have written out the title” in both watercolors, even if reluctantly.

I have only one severe caveat about the Blake Trust’s Grave. The verso of its title page includes the following in small type: “Design and production by John Commander.” I feel certain that he was the guiding hand for the entire project. His bibliographic wit gave birth to the brilliant idea of re-creating the original leather portfolio. Commander’s name should have been on the recto of the title page.

The Flying Horse publication does not have the eye-catching richness of the Grave watercolors and their presentation by the Blake Trust, but it is certainly a handsome object. The eighteen prints of Songs of Innocence and of Experience are printed on the rectos only of eighteen leaves, 19.5 × 14.l cm. These are fitted unbound into a re-creation of the buff paper wrappers, with string stitched through three stabholes on the front cover only, into which Catherine Blake bound some of her husband’s illuminated books—a nice touch roughly equivalent to the trust’s re-creation of the leather portfolio. The prints and their wrapper are housed in a rectangular well that is sunk into the right side of a triple-folding, four-section clamshell box, covered in finely woven dark-brown cloth, gilt stamped on the back and with a beige cloth interior; the accompanying paperbound pamphlet, 19.4 × 13.9 cm., is fitted into a depression on the left side of the box. Some may find that the container, at 37.0 × 132.5 cm. when fully opened, is out of proportion to its contents. The raised panels holding the prints and booklet measure a more modest 35.2 × 29.8 cm.

begin page 107 | ↑ back to topAs with the Blake Trust Grave, the pictures are the main event in the Flying Horse portfolio. These are the general title page from Songs of Innocence and of Experience and, from Innocence, the title page, “The Lamb,” “Holy Thursday,” “Nurse’s Song,” “The Chimney Sweeper,” both plates of “A Cradle Song,” and “The Divine Image.” Experience contributed its title page, “The Tyger,” “Holy Thursday,” “Nurses Song,” “The Chimney Sweeper,” “London,” “My Pretty Rose Tree” and its two companions on the same plate, “The Human Abstract,” and “A Divine Image.” The last is printed in black, as is the only impression definitely printed by Blake (Songs copy BB), all others in golden yellow ochre. As an untitled, unsigned essay at the beginning of the accompanying booklet explains, the yellow ochre ink is based on one that “Blake used in the first printing of the combined Songs” (7). The color accords with Songs of Innocence copies E and F (both probably printed 1789), and is a particularly close match to the Experience plates in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies B and D, printed in 1794 to join Innocence plates printed earlier in raw sienna.9↤ 9. For ink colors and printing histories, see Joseph Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993) 241-43, 267-75. Phillips dates the printing of Innocence copy E to “about the same time” as “the combined Songs in 1794” (25). Copies Band C of the combined Songs are available in the Blake Archive. Some of the Experience plates in copy E of the combined Songs are also from this first printing in yellow ochre; the ochre ink in copy C is a bit darker. The graininess and subtle variations in tone and texture of the Flying Horse prints replicate these characteristics in Blake’s own impressions.

The contrast between the ivory paper and the yellow ochre ink is not strong. In his own early copies of the combined Songs, Blake partly compensated for this by color printing and/or hand coloring the designs. The monochrome prints in the Flying Horse edition do not have this advantage. I wonder if the choice of ink color was the best. Blake also printed early impressions of Experience plates for copies of the combined Songs in green; that color would have made stronger pictorial statements without violating historical considerations. Some prints made by Phillips in the early 1990s—I believe from copperplates the same as, or very similar to, those used by Flying Horse—in blue and black inks have greater visual presence.10↤ 10. See the announcements for Phillips’s presentations to the Bibliographical Society, 20 Nov. 1990 (Innocence title page) and 17 Nov. 1992 (“Holy Thursday” from Experience). Both are on Whatman laid paper; my copy of the 1990 announcement has an “1801” watermark. Phillips very kindly gave me impressions from his “London” copperplate in black ink, one on laid paper and one on wove.

The unsigned essay (5-8) and Phillips’s “Note on Production” (9-31) in the booklet provide information about the Flying Horse impressions. They were “printed from relief etched copper plates made by Michael Phillips ... using exact-size photo negatives of original monochrome impressions.” The “negatives were modified to eliminate printing flaws in the original—such as poor inking, smudging and splattering—in order to establish the clearest and most complete example.” “Further refinements” were made on the copperplates “by scraping out unwanted details and adding missing ones” (5). “Each plate has been etched in two stages” (6) to the “same shallow depths as the America fragment” (23)—that is, the step-etched fragment of canceled plate a of America in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the only extant copperplate etched by Blake in relief. “The paper has been handmade to match the color, begin page 108 | ↑ back to top texture, size and weight of the wove papers that Blake used for printing, the illuminated books. The ink used to print this edition has been hand mixed for each plate from the same historic dry pigments that we know Blake used—and approximates as closely as possible the colors and texture of many of the originals. The facsimile relief etched plates have been inked using a leather-covered dauber, painstakingly building up the ink in stages on the relief surfaces” (6). Three copies of the combined Songs, B, C, and D, were “used to guide the way in which each facsimile plate has been wiped and printed for this edition” (6-7). “The inking of each plate with a leather dauber, and then wiping the plate ..., has consistently taken more than 30 minutes, and considerably more with some plates, before an impression could be taken” (23). The booklet includes four illustrations of the inking daubers, three in color.

This wealth of information raises as many questions as it answers. Exactly which “original monochrome impressions” were used as models? What is meant by “clearest and most complete example”? Example of what? Why the fiddling with the negatives and the copperplates?

To garner some answers, I e-mailed Phillips on 2 November 2009. His reply of the next day is both generous and fascinating. The copperplates used by Flying Horse were selected from “over 30” produced by Phillips in several stages over many years. Some of the plates began as photo-etchings based on the electrotypes printed in Alexander Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, 1863 and 1880. The photographic negatives, and later the images etched in copper, were corrected on the basis of “more than one impression of a plate ... until details that do not belong [in the copperplate image]—foul inking for example—[are removed] and others that do and are not present—the tail of a letter or tiny element of a design—are added in stop-out varnish by hand.” One such copperplate, the title page for Innocence, is reproduced in color in the booklet.11↤ 11. This is probably the same copperplate exhibited by Phillips at Tate Britain, 9 Nov. 2000-11 Feb. 2001, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 27 Mar.-24 June 2001. The plate, and several stages in its development, are illustrated in the catalogue; see Robin Hamlyn and Michael Phillips, William Blake (London: Tate Publishing, 2000) 105, 112. The sixteen Gilchrist prints could have supplied Phillips with models for only nine or ten of his eighteen plates.12↤ 12. Gilchrist includes the title page for Songs of Experience, but that would seem to be a re-creation rather than an electrotype mold-made from Blake’s original copperplate. If Phillips used this as the basis for his plate, it has been considerably modified in accord with Blake’s impressions. The eight Phillips/Flying Horse plates not among the Gilchrist electrotypes are the general title page, “Holy Thursday,” “The Chimney Sweeper,” and the second plate of “A Cradle Song” from Innocence, and “The Tyger,” “Nurses Song,” “The Chimney Sweeper,” and “A Divine Image” from Experience. The other eight plates in the Flying Horse portfolio have their origin in, or at least were corrected in response to, several copies of the Songs printed by Blake, including Songs of Innocence copy U (Houghton Library) and Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies O (Houghton Library) and BB (private collection). Phillips also consulted posthumous copy a of the combined Songs in the British Museum. His plate of “The Divine Image” bears two letters from the platemaker’s mark in white line lower right, as in posthumous impressions. For “A Divine Image,” he “used the [posthumous] impression in Geoffrey Keynes collection now in the Fitzwilliam Museum and the impression present in copy BB.”

I conclude from the booklet in the Flying Horse portfolio and Phillips’s e-mail that he has tried to recover and re-create the images on Blake’s copperplates. Thus the “clearest and most complete example” is a new copperplate that comes closest to Blake’s own. Surprisingly, this ambitious and worthy goal is nowhere made explicit in the publication, even though it would seem to be one of the guiding principles of the entire enterprise.13↤ 13. I would have printed “Blake’s Copperplates Re-created” as a sub-title in the Flying Horse booklet. While experimenting with relief etching in the 1970s, I was tempted to undertake a similar restoration, but took it no further than photo-etchings on zinc and copper without correcting these plates against multiple original impressions to recover Blake’s copperplate images and texts. Impressions from some of these plates, inked with a roller, were printed directly from the facsimile metal plates (not reproduced photographically from impressions) in Essick, William Blake’s Relief Inventions (Los Angeles: Press of the Pegacycle Lady, 1978). Another goal, one that receives ample attention in the booklet, is the recovery and reenactment of Blake’s inking and printing methods. When combined, these activities do not produce a “reproduction” or “facsimile” as I wish to define them here. Phillips’s alterations in the negatives and copperplates mean that no single impression by Blake (or by Frederick Tatham, the printer of posthumous impressions) is reproduced. Nor are the relief plateaus and white-line incisions on Blake’s own (lost) copperplates reproduced; rather, they are re-created. Impressions from those archaeological reconstructions are, in some senses of the term, “original” prints. They are an attempt to come as close as possible to publishing a new edition of Blake’s Songs.

How can we evaluate the accuracy of Phillips’s reconstructions? Posthumous copies of the

Songs offer some answers. They were printed rather flatly from the original copperplates and do

not contain the color printing, hand coloring, or special inking manipulations that grace Blake’s own

impressions but also diverge from the images etched in copper. Copy h, in my collection, contains fifty-seven

impressions of fifty-four plates, including “A Divine Image.” Many were poorly inked but printed with

considerable pressure; the resulting embossments create shallow molds of Blake’s copperplates as they

existed when Tatham was printing them c. 1832. These impressions provide a good benchmark by which to judge

the success of Phillips’s copperplates in re-creating the originals. Comparisons, with and without low-power

magnification, reveal only a few details that would appear to indicate differences between Phillips’s

copperplates and Blake’s:

“The Lamb.” The solid form on the ground lower right is differently shaped in the

original.

“Holy Thursday” (Innocence). Horizontal white lines at the bottom are

differently configured.

begin page 109 |

↑ back to top

“Nurse’s Song” (Innocence). A bit of white-line work in the large leaf

above “rs” in the title may not be in the re-creation.

“The Divine Image.” Phillips’s plate may not have the same configuration of white lines in

the vine left of the final two stanzas.

“Holy Thursday” (Experience). The dot of the question mark at the end of

line 4 of the text is missing, as in the Gilchrist electrotype.14↤ 14. Differences between the electrotypes and Blake’s copperplates are listed in

Essick, William Blake Printmaker (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980) 95. The outline between mountain and sky above and to the left of the standing

woman’s right hand is a single line in the original. This line is oddly fragmented, at least in the Flying

Horse impression from Phillips’s plate.

“London.” The hyphen is missing from “Chimney-sweepers” (line 9), as in the Gilchrist

electrotype.

Plate including “Ah! Sun-Flower.” The hyphen is missing from the title, as in the Gilchrist

electrotype.

All other differences, and perhaps even some of those listed above, can be accounted for by variations in inking and the wiping of etching borders (following Blake’s own practice in the 1790s) in the Flying Horse impressions. The “colophon” on a separate leaf in the Flying Horse publication states that “the copper plates for this facsimile edition were made by Michael Phillips from original William Blake impressions.” The repetition of characteristics indicative of the Gilchrist electrotypes and not Blake’s own plates leads me to question this statement for three of the Phillips copperplates. These may have been corrected in accord with “original William Blake impressions,” but the three details noted above overlooked. The electrotype of “Holy Thursday” (Experience) is missing part of the “n” in “rain” (line 14); the first plate of “A Cradle Song” lacks the first letter of “dreams” (line 3). These elements are present in the Flying Horse impressions.

Both the Flying Horse printer and Tatham, in his posthumous impressions, had difficulty capturing Blake’s fine white- line work, as I was able to confirm by consulting reproductions of a few impressions by Blake. Among the Flying Horse prints, this is a significant feature only in the second plate of “A Cradle Song.” Several of the prints from Phillips’s copperplates would seem to reveal more of the original copperplate image than Tatham’s prints, particularly in comparison to his miserably over-inked impression of the Innocence title page in posthumous copy h. Similar inking and printing differences can be found among Blake’s own impressions.

Comparisons between the Flying Horse publication and the uncolored issue of the Manchester Etching Workshop portfolio of 1983 are inevitable.15↤ 15. Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience (Manchester: Manchester Etching Workshop, 1983). “Monochrome Edition” limited to thirty-five copies each with nineteen plates, two hand colored, boxed loose in folders. See also Joseph Viscomi, “Recreating Blake’s Illuminated Prints: The Facsimiles of the Manchester Etching Workshop,” Blake 19.l (summer 1985): 4-23, and my review of both the colored and uncolored editions in the same issue, 39-51. Phillips himself initiates such comparisons by noting, in the Flying Horse booklet, that the Manchester copperplates were etched much more deeply than the America fragment and his Songs plates (33n2).16↤ 16. Phillips cites Paul Ritchie of the Manchester Etching Workshop as the source for information about depth of bite in its copperplates. In The Art of William Blake’s Illuminated Prints included in the Manchester portfolio, Viscomi suggests that “the depth of plates executed before 1793 was probably greater than of those executed afterwards” (12). Perhaps the similarity is accidental, but the Flying Horse folding box is covered in brown cloth only slightly darker than the cloth covering the folding box housing the Manchester prints and their accompanying paperbound booklet, The Art of William Blake’s Illuminated Prints, by Joseph Viscomi. Both editions are printed on handmade paper produced specifically for their projects, the Manchester leaves with a blind-embossed “Inv / WB” and some Flying Horse leaves showing a “WB” watermark. Both sets were printed from photo-etched copperplates; sixteen of the Manchester plates, like some of Phillips’s, used the Gilchrist electrotypes as prototypes, although in somewhat different ways.

Detailed, letter by letter and motif by motif, comparisons between the Manchester and Flying Horse impressions would be tedious and serve little purpose. Both are important publications, the products of expertise and dedication; both attempt to recapture Blake’s original copperplate images. Both sets were printed on softer paper than is typical of Blake’s impressions, thereby creating more prominent platemarks and embossments of small relief elements, such as letters. The Manchester set restores to the impressions the three textual details, noted above, missing from the Gilchrist electrotypes and the Flying Horse plates.17↤ 17. Viscomi, “Recreating Blake’s Illuminated Prints,” comments that “we corrected the missing characters in a matching ink on the impressions themselves, rather than correct the electrotypes” (6). The Manchester Etching Workshop had a set of electrotypes, mold-made from the Gilchrist set, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, but by “electrotypes” I take it that Viscomi means in this statement the photo-etched copperplates based on impressions of the electrotypes, the production of which is explained on page 5 of his essay. Following combined Songs copy B as a precedent, the Manchester plates of Innocence were printed in raw sienna, the Experience plates in a yellow ochre a little darker than the yellow ochre of the Flying Horse prints. The Manchester inks make a stronger visual impact. The plates were inked with a roller, and thus have more evenly printed surfaces than the Flying Horse impressions, inked with leather-covered daubers.18↤ 18. Viscomi states that Paul Ritchie of the Manchester Etching Workshop “applied the ink ... with a roller, rather than a linen dabber, the tool Blake most likely used. We resorted to the ‘unBlakean’ tool ... because it produced more consistent results. With dampened paper, light printing pressure, and stiff handmade intaglio ink, we succeeded in duplicating the surface texture, as well as the colors of the originals” (“Recreating Blake’s Illuminated Prints” 7). For a detailed but rather inconclusive discussion of Blake’s possible inking tool(s), see Essick, Printmaker 99-102. Rollers had not been invented until very late in Blake’s career; he probably inked his relief-etched plates with either leather-covered or linen-covered inking balls. Thus, the inking of the Flying Horse begin page 110 | ↑ back to top plates comes closer to Blake’s own practices. This difference in inking methods between the Manchester and Flying Horse impressions underscores the tension between an attempt to re-create aesthetically pleasing prints with the visual qualities of Blake’s own and an attempt to reenact his processes. In my review of the Manchester portfolio I complained (mildly) about the rough texture of the paper on which the plates were printed. To my eyes, the texture and lighter color of the Flying Horse paper are a little closer to Blake’s own. We should, however, be grateful for the instructive differences between the two publications. Except for the minor problems noted here, I suspect that the Manchester and Flying Horse editions of Blake’s Songs are as close as we are likely to come to new prints from Blake’s own plates—short of a discovery even more breathtaking than the nineteen Grave watercolors.

Much of Phillips’s essay in the Flying Horse portfolio deals with Blake’s own etching and printing methods rather than with their reenactment. Many of his observations are controversial, including the depth of bite in Blake’s early relief etchings and the type of inking instrument he used (see notes 16 and 18 here). Phillips relies heavily on the description of Blake’s methods in Jackson and Chatto, A Treatise on Wood Engraving, and particularly their comment that Blake “was accustomed to wipe the ink out where it had touched in the hollows. As this occupied more time than the mere inking of the plate, his progress in printing was necessarily slow.”19↤ 19. [John Jackson and William Andrew Chatto], A Treatise on Wood Engraving, Historical and Practical (London: Charles Knight, 1839) 716- 17. Phillips believes that the Jackson and Chatto account has considerable authority because it “suggests that they visited Blake in his studio at No. 3 Fountain Court, the Strand, some time between Jackson’s arrival in London in 1824 and Blake’s death in August 1827” (11). These statements and Phillips’s own experiences with relief printing lead him to conclude that Blake’s art of illuminated printing required exacting craftsmanship and painstaking, time-consuming labor. For Phillips, “the evidence” shows “that the processes of creation and reproduction were rarely accomplished simply or easily” and that “Blake’s method of production was neither simple nor efficient ....”20↤ 20. Phillips, “The Printing of Blake’s America a Prophecy,” Print Quarterly 21.1 (2004): 20n5, 38.

In the 453 double-column pages of Blake and the Idea of the Book, Viscomi does not cite the Jackson and Chatto description of Blake’s method and, in stark contrast to Phillips’s views, claims that “inking small relief plates ... and printing them ... was relatively easy” and that, “working alone with handmade ink and a linen dabber,” he “pulled thirty good impressions” from “electrotypes” of the Songs of Innocence title page and “The Lamb” in “less than two hours.”21↤ 21. Blake and the Idea of the Book 118, 397n22. See also Viscomi, “Illuminated Printing,” The Cambridge Companion to William Blake, ed. Morris Eaves (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) 41: “Illuminated printing was not mysterious, complex, or difficult.” My own study of Blake’s prints etched in relief led me to conclude that, “in the majority of his relief etchings, Blake did not have to wipe bitten surfaces in order to keep them clean enough to meet his own inking and printing requirements.”22↤ 22. Essick, Printmaker 104. I have consistently emphasized the ways in which relief etching is a direct and autographic process joining invention and execution, one that freed Blake from the trammels of his profession as an intaglio engraver of other artists’ designs. These practical characteristics allowed Blake to claim that his process “combines the Painter and the Poet” and “produces works at less than one fourth of the expense” of “Letter-press and Engraving.”23↤ 23. “To the Public,” The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman (New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988) 692. I suspect that part of the savings in “expense” can be accounted for by savings in labor. These differing views are not merely trivial disputes over technical details, for they evince fundamentally different visions of Blake. Perhaps Viscomi and I could be accused of succumbing to a now-discredited romantic ideology in which “first thoughts are best in art, second thoughts in other matters.”24↤ 24. A remark attributed to Blake in Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1863) 1: 370. Perhaps Phillips could be accused of assuming that original composition and execution are as time-consuming as replication and succumbing to a modernist literary ideology in which complexity is the hallmark of genius.

This is not the place to engage further in this long-running debate. Rather, it is the time to welcome, indeed to celebrate, the two publications of scholarship and beauty which it has been my pleasure to review in Blake.