note

WILLIAM BLAKE AND HENRY EMLYN’S PROPOSITION FOR A NEW ORDER IN ARCHITECTURE: A NEW PLATE

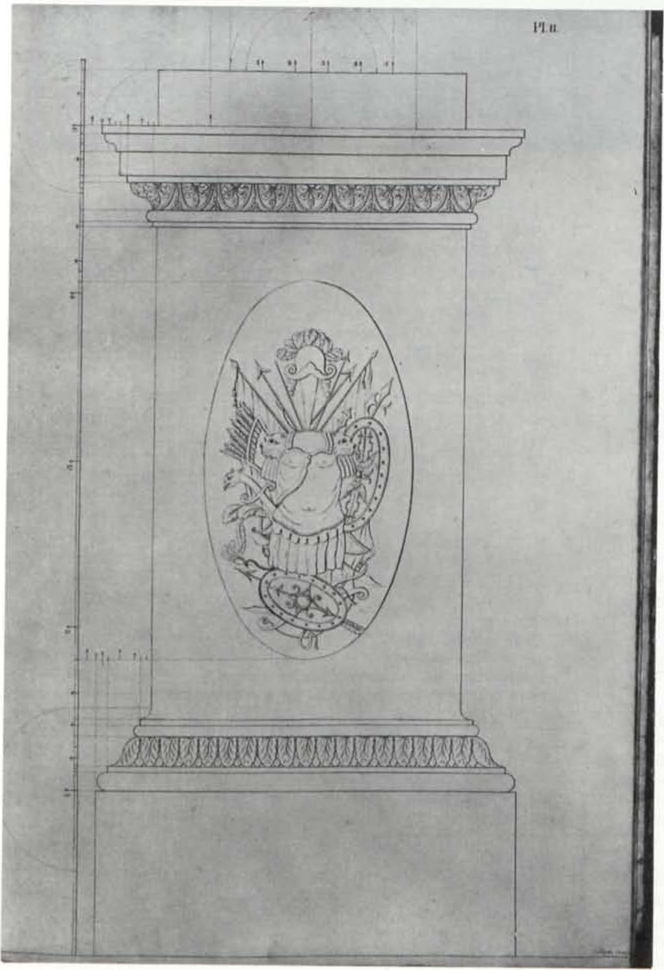

Very early in his professional life as an articled engraver, William Blake made one sally into the business of reproducing architectural designs in a publishable form. He engraved at least one of the designs which accompanied Henry Emlyn’s A Proposition for a New Order in Architecture (London, for J. Dixwell, 1781).1↤ 1 This plate was first noticed by William A. Gibson in the British Museum in 1966, while doing work supported, in part, by the Ohio State University Development Fund through its Faculty Summer Fellowship program, and by a grant from the Penrose Fund of the American Philosophical Society. Plate II [fig. 1] in both the first and second (1784) editions of Emlyn’s treatise is clearly signed “Blake sculp.” This plate is of interest for several reasons. It is among Blake’s earliest commercial jobs.2↤ 2 It is certainly among the first five or six pieces which he did on his own after leaving Basire. Indeed, since it was not uncommon for the engravings which would accompany a book to be completed long before publication of a volume, the Emlyn plate may antedate all the rest of Blake’s early commercial work except perhaps his single plate for J. Oliver’s Fencing Familiarized (1780). For a list of Blake’s earliest work, see Gerald E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 609. It is his only known work in engraving plans or directions for architects, although, of course, he showed an interest in architecture in much of his art.3↤ 3 Expressions of Blake’s interest in architecture range from the homely sketch of his Felpham cottage in Milton, plate 36, to his engravings for Stuart and Revett’s Antiquities of Athens. But the engraving he did for Emlyn’s treatise is unique of its kind in the body of Blake’s work. And the plate is among Blake’s largest engravings. It measures 537 mm. high in the platemark, and about 370 mm. wide. We give the measurement of width as approximate because most copies have been cropped, and measurement of this dimension is uncertain, sometimes impossible. The platemarks are light, and the width suffered most in binding.

Emlyn’s treatise is now very rare. Of the first edition we have traced three copies in England; one is in Sir John Soane’s Museum, another is in the private library of Mr. John Harris, Curator of the Drawings Collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and recently a third copy was offered for sale by Mr. Paul Breman of London.4↤ 4 The treatise was offered for sale by Mr. Paul Breman of Paul Breman Ltd., 7 Wedderburn Road, London NW3. The Emlyn volume is item 12 in his catalogue 14, “English Architecture 1598-1838,” priced at £345. In the United States the only known copy is in the collection of Mr. Lessing J. Rosenwald. Of the second edition we have located two copies, one in the British Museum, shelfmark 1733.d.25, and another in Cambridge University Library, bought from King’s College Library in 1923. The third edition of 1797 is the commonest; there are copies in the British Museum, the library of the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Avery Library of Columbia University, the Print Room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and elsewhere. But for this edition the plates were reduced to a platemark of 445 mm. by 282 mm.

Henry Emlyn (c. 1729-1815) was an obscure Windsor carpenter.5↤ 5 See H. M. Colvin, Biographical Dictionary of English Architects 1660-1840 (London: John Murray, 1954), p. 195. He tried in his treatise to establish a native English order in architecture to rival the orders of classical origin, basing his plans for the column on an analogy with the oak that flourishes in Windsor Forest. To support the column, Emlyn proposed a formal pedestal at the center of whose die stone is an heraldic trophy. This pedestal is the subject of Plate II of the first edition, the plate which bears Blake’s signature. Such trophies were common devices. Similar ones (but none close enough to be considered Blake’s or Emlyn’s model) appear in Piranesi, and visitors to London today can see others atop the gateposts of the Royal Chelsea Hospital (see fig. 2, a sketch of a trophy provided by Mr. Peter Spurrier of the Chelsea Arts Club).

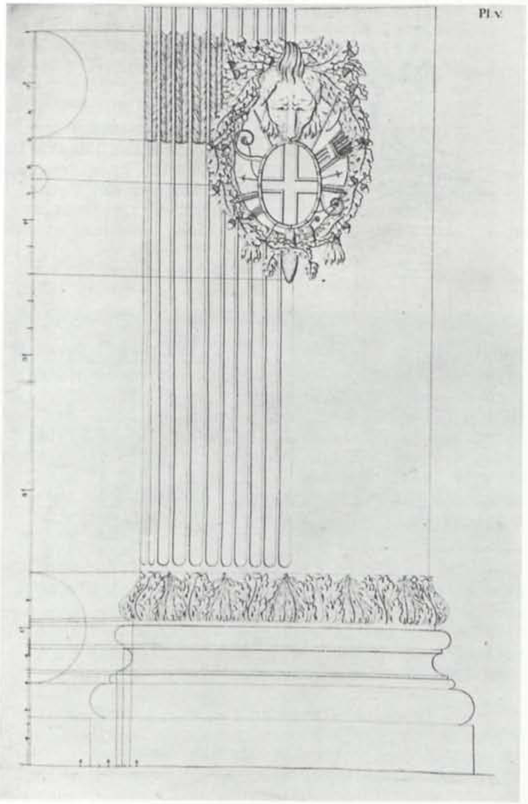

In Emlyn’s order a single elliptical shaft rises to a fifth of the total height, then divides into two thin circular shafts; at the fork of the column Emlyn placed the Shield of the Order of Saint George. This shield is the focus of Plate V [fig. 3], which Emlyn describes as follows: “The Knights Shield and Armour, with the Skin of a Wolf, hanging down on each Side, and bending down the twigs of the tree; all which together Cap the Center begin page 14 | ↑ back to top

The architectural elements and their ornaments do not provide such precise points of comparison as the numerals and dimension lines, for the trophy on the signed plate [fig. 1] is less intricate in its detail and more sharply outlined than the coat of arms on the unsigned one [fig. 3]. Yet even here a close examination reveals some similarities in line and execution. The modelling of the breast of the armored trophy is created by the same curved lines as those that compose the lion’s facial features in the coat of arms. The volute at the lower right-hand corner of the oval shield in the coat of arms has the same configuration as the volutes on the hilts of the two swords in the trophy; and it is also the same as the volute that adorns the forehead line of the helmet seen in profile at the hips of the trophy’s torso. While it must be admitted that the eyes of the volute at the ends of the bow in figure 1 are tighter than those on the bow in figure 3, the curves of both bows have similar sweeping rhythms. The open-eyed volutes of figure 3 do repeat those of the ornaments to the bottom shield in figure 1; they also resemble the volutes with which Blake has adorned the “B” of his own name. And again, the pointed fletching of the arrows in the sheath of figure 1 is outlined and textured by the same short, wedge-shaped lines as those that form the fletching in the fluting of figure 3. A close examination of such features as the plumes, leaves, acorns, fleurs-de-lis, and animal motifs would be instructive but appropriate only in a fuller study of Blake and Emlyn. We might note, however, that Plates I, III, VI to X, and XVIII are also unsigned and could be by Blake. Several plates (XI to XVII and XIX to XXI) are signed “Sparrow sculp.”; Plate IX of the unsigned plates resembles Sparrow’s work.

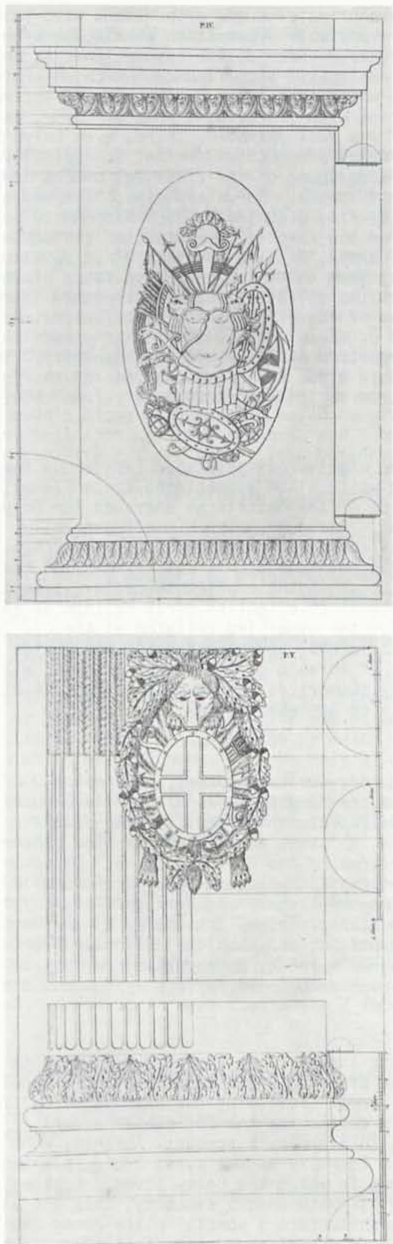

The plate originally signed by Blake (Plate II, 1781—fig. 1) has almost certainly been reworked, rather than re-engraved entirely, for the scaled-down version in the third edition (Plate IV, 1797—fig. 4). The numerals along the left vertical scale appear to be identical in both versions, as well as the horizontal dimension lines and the heavy and light lines of the vertical scale itself. A few vertical dimension lines have been eliminated from the left side of the plate, but new scales and dimension lines have been added to the right side to replace them. The fleur-de-lis and leaf designs on the cyma reversa and cyma recta mouldings respectively remain intact. The trophy itself appears to be most extensively altered, but the changes are in fact nothing but additions carefully fitted into the open spaces within the oval framing line. The points of the newly added anchor, for example, just touch the edges of the original upper shields and swords. The new anchor cable runs through open spaces between the original emblems, begin page 15 | ↑ back to top with its free end apparently hidden somewhere behind the lower helmet or its plume (the cable happily tightens the composition of the entire trophy, for it helps to link the spears and upper helmet to the torso). The compass and chain are similarly integrated with the original emblems so as to change virtually none of their outlines. Cropping the plate to the new dimensions provided no special problems for the engraver. To shorten the plate the dimension lines at the top have been eliminated, the top plinth thinned slightly, and the tall bottom plinth reduced to a sliver. To narrow the plate the margins have simply been cropped, necessitating only the elimination of a semi-circular dimension line at the left. If our argument is correct, this plate in the third edition remains largely Blake’s work.

Since Plate V could not be so easily cropped, it was entirely re-engraved, with some loss of the original grace, for the third edition (Plate V, 1797—fig. 5). The scale—now on the right side of the plate—is more difficult to interpret than the original one, and the numerals far more conventional in their configurations. The individual oak leaves in the border framing the shield have lost their original undulating curves; the paws hanging below are now thick-ankled and club-like. The lines intended to model the lion’s face only make the lion appear old, tired and wrinkled. We can only speculate whether the same engraver is responsible for both this plate and the alterations of Blake’s plate. The most obvious similarities between the new plate and the alterations are the reliance upon short, light dashes for dimension lines and the hard outlining of such emblems as weapons, animal motifs, chain, cable, and anchor.

Mr. Breman’s remark about the “obvious parallel between Emlyn’s work and that of the French architect Ribart Chamoust, whose ‘L’ordre francois trouvé dans la nature’ appeared two years later,”7↤ 7 Breman, item 12. fails to suggest the significance of either work. Both represent the rather desperate attempts of late eighteenth-century architectural theorists to establish new aesthetic premises on which to base architectural criticism and design. As Rudolf Wittkower has demonstrated, the theological-philosophical bases of Renaissance architectural theory were being undermined by the development of new habits of thinking.8↤ 8 Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, 3rd ed. (London: Alec Tiranti, 1962), pp. 142-54. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the old systems of mathematical and harmonic proportion were increasingly being ignored, misunderstood, or half-consciously avoided.

Emlyn’s attempt is not, however, an entirely new departure. Vitruvius traces the evolution of the orders from primitive man’s looking to trees as his first models for supporting columns in building (De Architectura, II.i.4). Even Isaac Ware, whose encyclopedic Complete Body of Architecture (1756) ignores entirely the theological-philosophical bases of Renaissance theory, begins his affirmation of

One might profitably speculate about the extent to which Blake appreciated the emblematic significance of the details he engraved for Emlyn’s treatise. Although Emlyn himself generally stresses the political and moral rather than the religious meanings of his motifs, many of the same motifs occur in the eighteenth-century treatises that attempt to establish Great Britain as an early haven for the undefiled religion of the Old Testament patriarchs, and to establish the Druids as the priests of Abraham’s faith. For example, William Stukeley summarizes the new legend thus in his treatise on Stonehenge: ↤ 12 Stonehenge, A Temple Restor’d to the British Druids (London, 1740), Preface, n. p.

The patriarchal history, particularly of Abraham, is largely pursu’d; and the deduction of the Phoenician colony into the Island of Britain, about or soon after his time; whence the origins of the Druids, of their Religion and writing; they brought the patriarchal Religion along with them, and some knowledge of symbols or hieroglyphics, like those of the ancient Egyptians; they had the notion and expectation of the Messiah, and of the time of year when he was to be born, of his office and death. 12The major link between Stukeley and Emlyn is the oak tree of Windsor Forest, the primary model for Emlyn’s order (following the example of Callimachus’s design for the Corinthian order).13↤ 13 Vitruvius, IV.i.10-11. According to Stukeley’s account, Abraham, whom he seems to identify as the first Druid, planted an oak grove in which the Deity lived. Besides endowing the oak with unique sanctity, this act also gives architecture a special place among the arts: “From these groves arose the first ideas of architecture. first [sic] was it employ’d for sacred purposes.”14↤ 14 William Stukeley, Palaeographica Sacra (London, 1763), pp. 8, 17. Another motif that arouses some curiosity is what appears to be a ram’s horn on the helmet crowning the trophy (fig. 1). Stukeley associates the ram’s horn with Jupiter Ammon, and thence back to a religious and political ritual of the ancient Israelites.15↤ 15 Stukeley, Palaeographica Sacra, pp. 59-60.

This preoccupation with religious emblems, with the early history of an uncorrupted faith, with Druid lore, and with the establishment of religion and learning in prehistoric Britain is one that Blake shared with such men as John Toland, William Stukeley, John Wood of Bath, and Henry Emlyn. Blake surely knew Stukeley’s companion volume to Stonehenge, Abury, and he knew it perhaps as early as 1773 when Basire copied part of one of the plates from Abury for an illustration to Jacob Bryant’s A New System, or an Analysis of Ancient Mythology (3 vols., 1774-76) for which Blake engraved at least one plate. John Beer has recently suggested that Blake’s early engraving after Michelangelo, later titled “JOSEPH of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion,” resembles an engraving in Sammes’s Britannia Antiqua Illustrata and another in Stukeley’s Stonehenge. 16↤ 16 John Beer, Blake’s Visionary Universe (Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press, 1969), pp. 15-19. See also Peter F. Fisher, “Blake and the Druids,” JEGP, 58 (1959), 589-612, and especially Ruthven Todd, Tracks in the Snow (London: The Grey Walls Press, 1946), pp. 29-60. But of course Blake was also familiar with other studies of Druid lore, widely popular in the antiquarian researches of the 1770’s and 1780’s. To this varied body of works Emlyn added a treatise which might well have been congenial to Blake as encouraging the kind of native “republican art” Blake envisioned would reinvigorate his England.

As far as is known, Emlyn’s designs were attempted in stone only once, at Beaumont Lodge in Berkshire. A house had stood at Berkshire since at least the seventeenth century, but Henry Griffiths, who purchased the estate in 1789, had it embellished with the British Order. Work was completed about 1790.17↤ 17 Sandra Blutman, “Beaumont Lodge and the British Order” in H. M. Colvin and John Harris, eds., The Country Seat: Studies in the History of the British Country House Presented to Sir John Summerson (London: Allen Lane, 1970), p. 181. Perhaps unfortunately, in this only begin page 17 | ↑ back to top instance, the trophy which Blake engraved was not used, and Griffiths chose the seal of the Order of the Garter instead of the Shield of the Order of St. George to mark the column’s fork. As Miss Sandra Blutman writes, “Poor Emlyn’s order was doomed to failure. It was never copied or adapted to modern requirements and Beaumont Lodge, an otherwise rather ordinary Georgian house, stands empty today—the only surviving example of this curious idea.”18↤ 18 Blutman, p. 184.

Beaumont Lodge was, interestingly enough, beside the home of Blake’s friend of later years, George Cumberland, who bought his estate in Windsor Great Park in 1792.19↤ 19 Geoffrey Keynes, “Some Uncollected Authors XLIV: George Cumberland 1754-1848,” Book Collector, 19 (1970), 38. Did Blake ever see the British Order executed in stone? Perhaps, for he might have visited Cumberland at Bishopsgate, as Cumberland visited Lambeth. Cumberland, at least, probably did know Beaumont Lodge, for he had a dispute with Griffiths about a destitute family which had squatted, with Cumberland’s permission, on some waste land between the two houses.20↤ 20 Keynes, p. 60. The altercation found its way into print in Cumberland’s A Letter to Henry Griffiths, esq., of Beaumont Lodge (1797), to which came the due response, Mr. Griffiths’ Remarks, upon the Letter Signed George Cumberland (1797).

As a final note we might remark that the third edition of Emlyn’s treatise (1797) was printed by one “J. Smeeton, St. Martin’s Lane, Charing Cross.” This is the same house, reestablished after a fire, as “G. Smeeton, Printer, 17, St. Martin’s Lane, London,” that set the second prospectus of Blake’s “Canterbury Pilgrims.”21↤ 21 See David V. Erdman, ed., The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, 4th printing, rev. (Garden City: Doubleday, 1970), p. 559. This connection provides, however, no reason to suppose that Blake was involved in the re-engraving for the third edition. He was by then engaged with other work.

In preparing this announcement the authors have benefited from the generous help of several individuals and institutions. We are grateful to Professor G. E. Bentley, Jr., Mr. Paul Breman, Mr. James Carter, Mr. Paul Grinke, Mr. John Harris, Sir Geoffrey Keynes, Miss Michèle Roberts, Mr. Lessing J. Rosenwald, Mr. Peter Spurrier, and Sir John Summerson; and to the Avery Memorial Library of Columbia University, the British Museum, the Print Room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Sir John Soane’s Museum. Our special thanks go to Mr. Ruthven Todd who throughout this project has given of his time and wide knowledge of Blake, and who has willingly opened for us doors of whose existence we were too often ignorant.