note

TWO BLAKE DRAWINGS AND A LETTER FROM SAMUEL PALMER

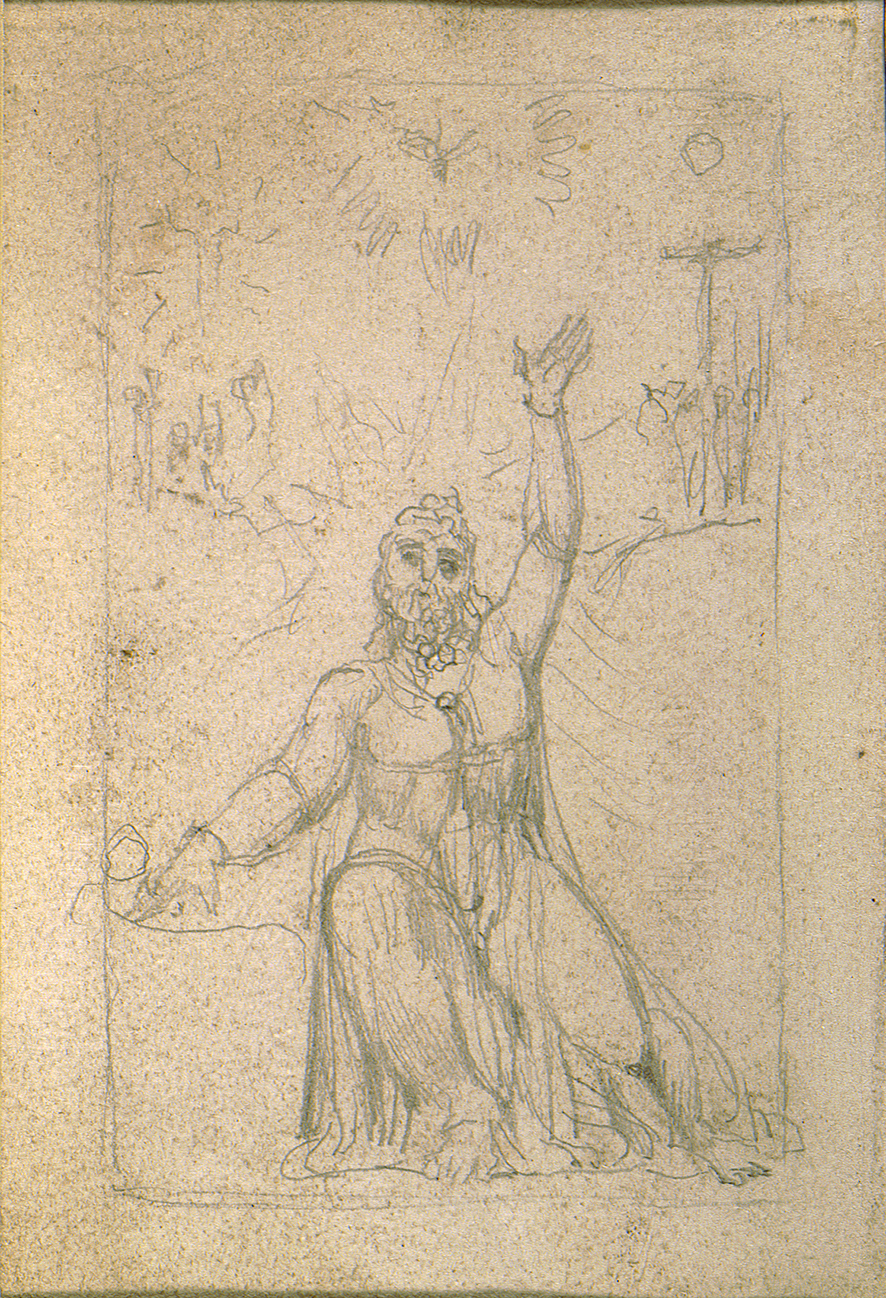

In the Department of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum are two sketches by Blake, one on either side of the same piece of paper, of “Isaiah foretelling the Crucifixion” [illus. 1 and 2]. They are thought to have been made about 1821, measure 4 3/4 by 3 inches, and came from the collection of Samuel Palmer.1↤ 1 Geoffrey Keynes, Blake’s Pencil Drawings, 2nd series, (London: Nonesuch Press, 1956), pl. 39. The two sketches are two stages in the development of the composition, the second, more detailed sketch being inscribed in Palmer’s hand: “The ‘First Lines’, on the preservation of which Mr Blake used so often to insist, are on the other side.”

The prophet is shown seated, with his left hand on an open scroll, and his right hand raised above his head. The background details of the second sketch show, from left to right, the Crucifixion, the Holy Ghost as a dove, and the Ascension. The sketches were obviously preliminary studies for a third, almost identical, drawing on a wood block, also in the British Museum, which depicts “Isaiah foretelling the destruction of Jerusalem.”2↤ 2 Drawings of William Blake 92 Pencil Studies (New York: Dover Publications, 1970), pl. 83.

Accompanying the sketches is a fragment of a letter from Samuel Palmer to an unknown addressee. It is undated, but from the handwriting and signature, begin page 54 | ↑ back to top I would roughly assign it to about 1849; and from the allusion to the spring in the last paragraph, it would appear to have been written during the autumn, or perhaps during the winter.

↤ 3 Palmer is wrong here. Blake’s Pilgrim’s Progress designs were made about 1824. There were twenty-nine of them and they are reproduced in color in The Pilgrim’s Progress, introduction by Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Spiral Press, 1941). ↤ 4 Palmer did, in fact, own Blake’s tempera picture, “The spiritual form of Pitt, guiding Behemoth,” now in the Tate Gallery, London. Palmer refers to this in a letter to George Gurney, written in October 1880 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). It is, of course, possible that the tempera did not come into Palmer’s possession until after the letter in the British Museum was written. Cf. Martin Butlin, William Blake: A Complete Catalogue of the Works in the Tate Gallery (London: Tate Gallery, 1971), pp. 56-57.Allow me to contribute to your Album 2 small and faint—but undoubtedly genuine Blakes.

By attaching a thin piece of paper at one side, they can both be visible on turning over—The fainter is a design perhaps from the Pilgrim’s Progress3—the first inventive lines—from which he was always most careful not to depart. But finding that it was the right hand which ought to have been elevated he has traced the lines through at the window and gone on a little, intending then to transfer the second to another paper for completion which he probably did. The state in which Blakes drawings and those of other inventors are most interesting to myself are either the finished state or that in which the first thought is just breathed upon the paper—of the latter—the faint side of the enclosed is a fair specimen. Would that I had one, only one specimen of his finished work—but I cannot send you such, as I never possessed it.4

How long it is since we have met! You must take Time by the forelock if we live till the spring, and come and see what care has been taken of those excellently contrived anti-dust-hangings which you made for my study shelves. They remind daily of your kindness.

Yrs ever truly

S. Palmer—

One of the most interesting aspects of the letter is the light it throws on Blake’s method of work—his inability or unwillingness to depart from “the first inventive lines.” This no doubt explains much of the vitality and immediacy of his work. In the work of many painters, the difference between the original conception and the finished composition is vast. That is why, for example, Constable’s sketches and drawings are so often more moving than his canvases. And it is one reason why Blake is as powerful in his finished works as in his initial inspirations.