note

THE STATES OF PLATE 25 OF JERUSALEM

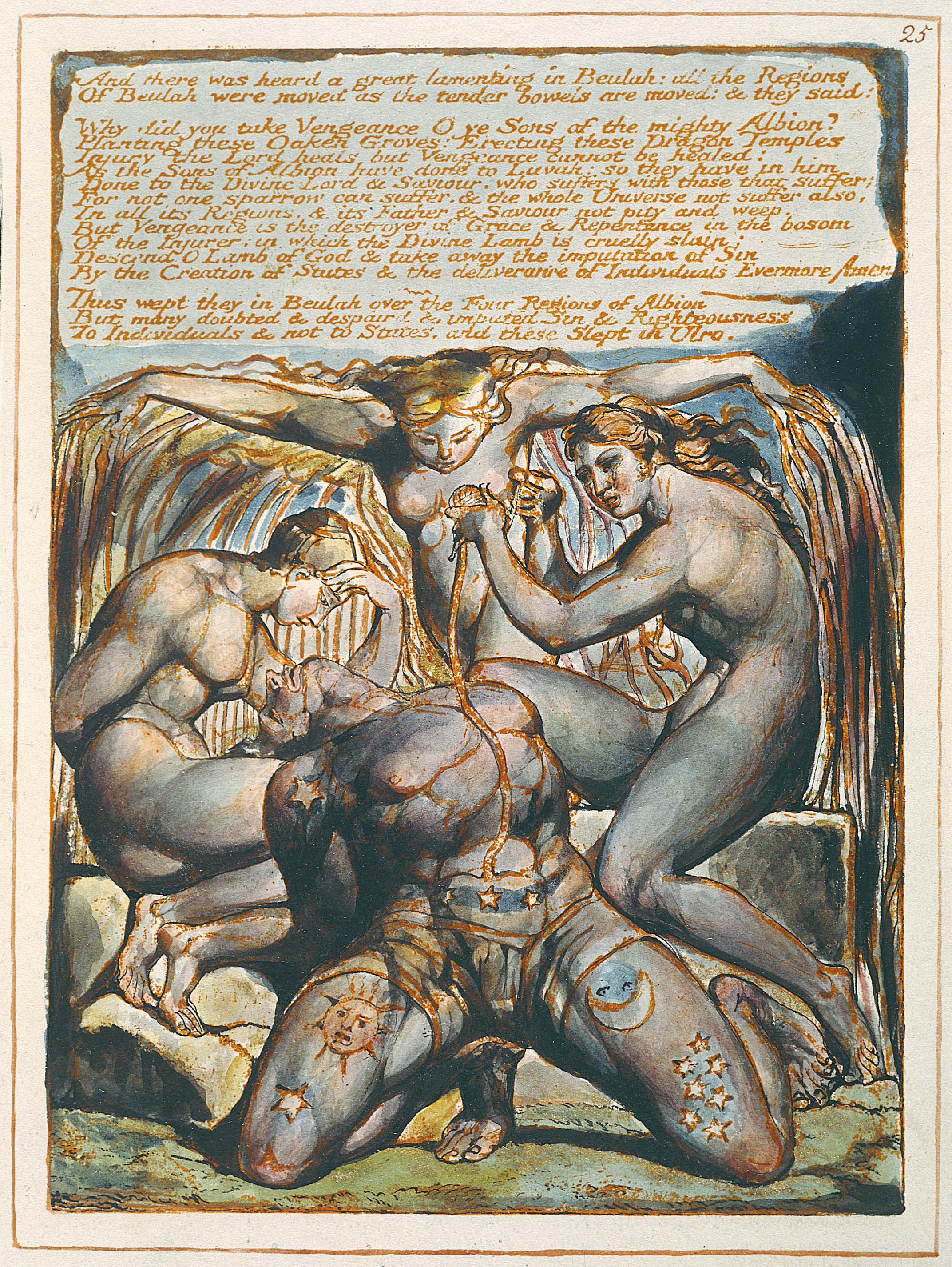

Plate 25 of Blake’s Jerusalem exists in three states. The Preston Proof Plate, the British Museum copy, the Rinder copy and the Cunliffe copy are all in the first state. The Harvard and Mellon copies are in the second state. The Pierpont Morgan and all posthumous copies are in the third state.

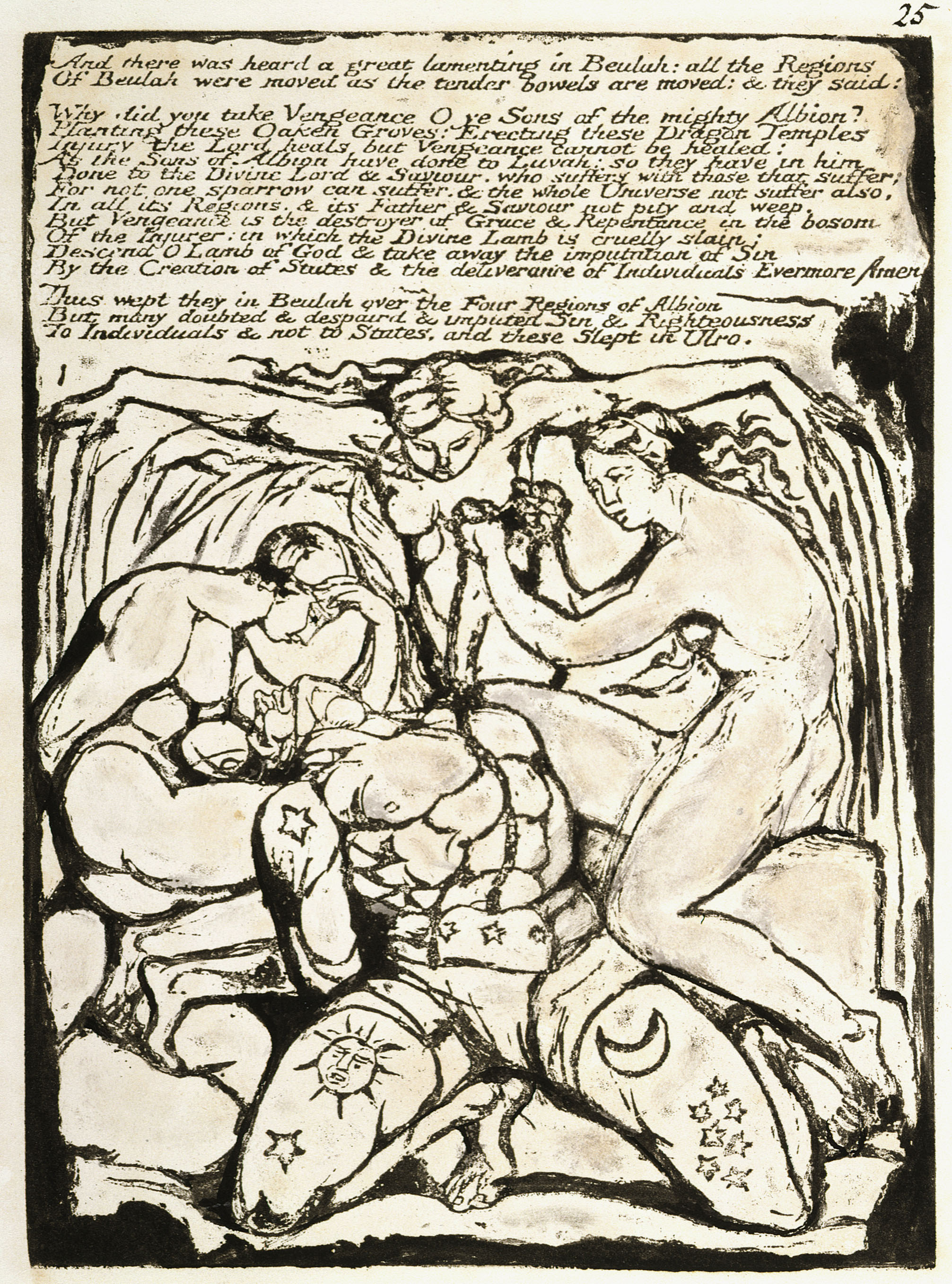

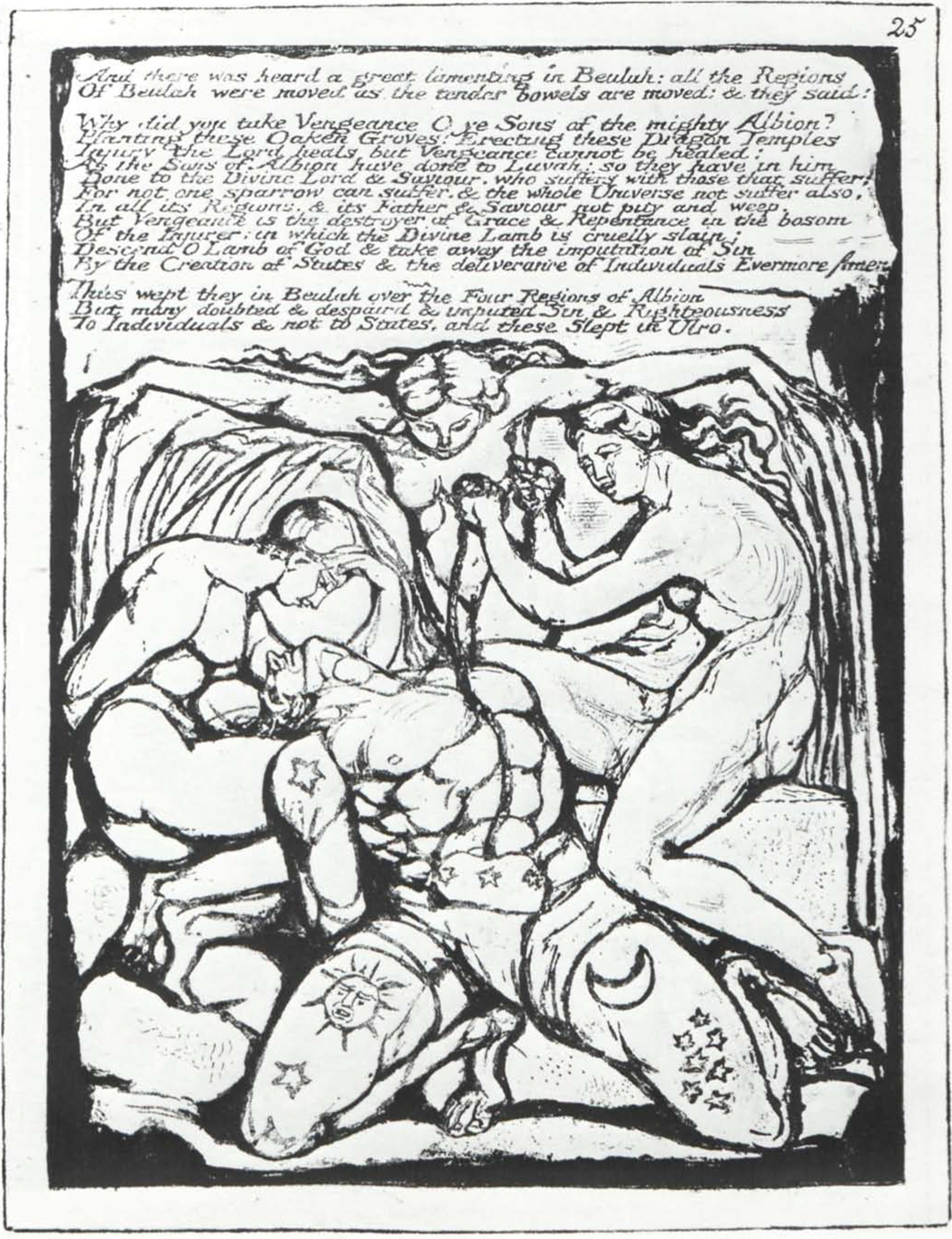

When one compares Plate 25 in the British Museum copy [illus. 1—see the front covers for all five illustrations] with that in the Harvard copy [illus. 2], major differences are immediately obvious. In the background of the Harvard copy additional fibers are present under the central female’s right arm. Small horizontal lines have been added between the right-hand female’s head and hands and above the central female’s left hand. Similar lines, though wavy, are present in the space above the right-hand female’s lap, in the text between “bosom” and “Evermore Amen” and to the right of the central female’s head. The rocks are slightly stippled and roughly cross-hatched, as is the ground in front of Albion. A line is present along the edge of the square stone block. A considerable amount of anatomical detail has been added to the figures. The right-hand female has received the most attention. A whole series of details has been added to her back, shoulder, upper arm, thighs and calf. She has also received an additional lock of hair in the small of her back and a line clarifying her jaw. Her left eye has been redefined and two tears have been added on her cheek. Albion has received four delicate lines on his upper chest and two small lines on the inside of his right thigh. From my point of view the most interesting change is that to the central figure, who receives a clearly marked pudendum reminiscent of the Rosso Tre Parche. 1↤ 1 See Morton D. Paley and Deirdre Toomey, “Two Visual Sources for Plate 25 of Jerusalem,” Blake Newsletter, 5 (Winter 1971-72), 185-90.

begin page 47 | ↑ back to topIt is interesting to note that nearly all the changes of the second state are anticipated, in the British Museum copy, by light grey wash shading in the relevant areas. This anticipation is particularly exact in the areas above the central figure’s left arm and in the text between “bosom” and “Evermore Amen.”

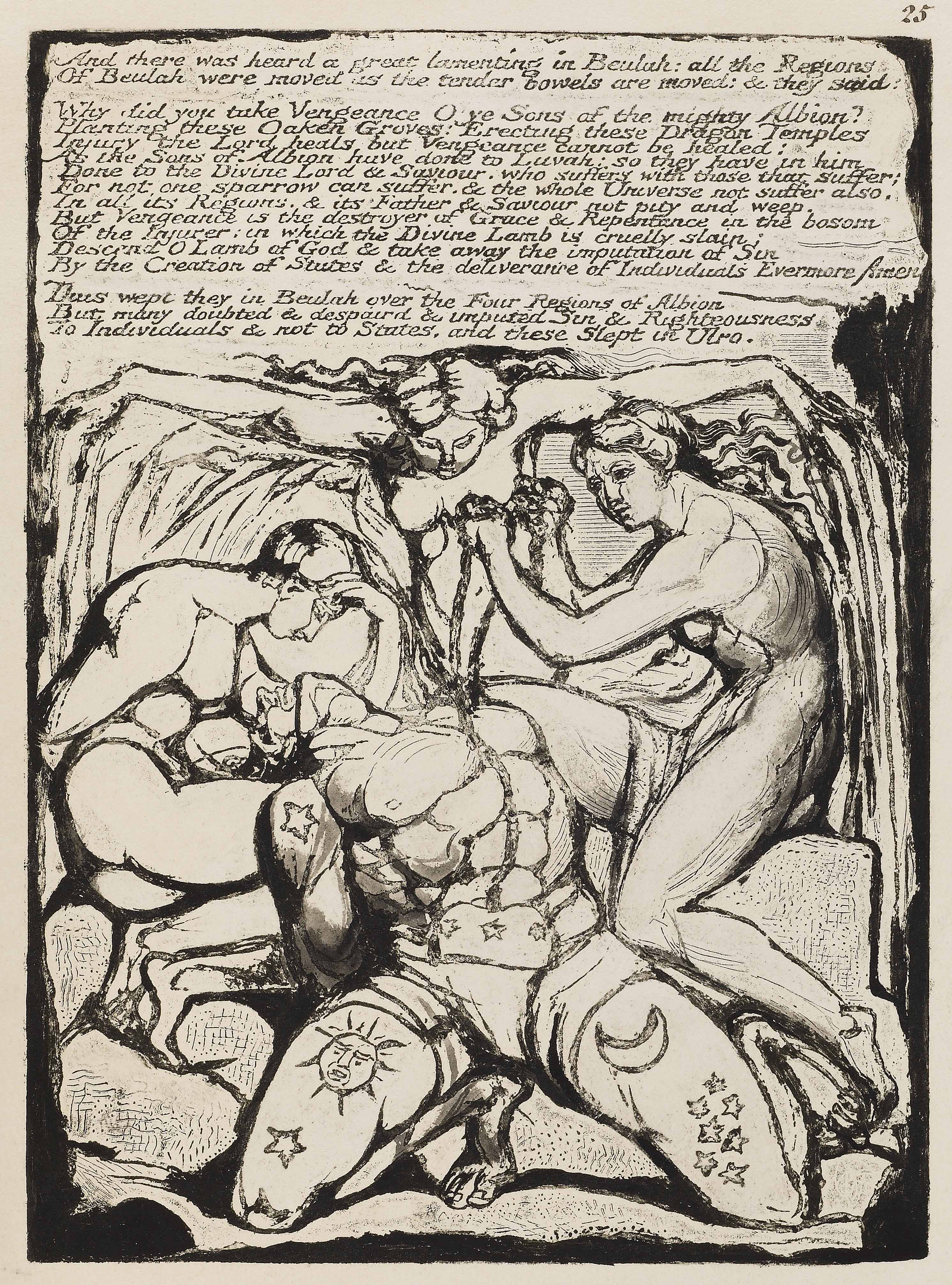

The Mellon copy [illus. 3] is clearly in the same state as the Harvard. Despite the tendency of the wash to obscure etched details, the grainings on the rocks and in the foreground show through in the orange-brown printing ink, as do some of the anatomical changes. The Cunliffe copy can be safely assigned to the first state for the same reasons. In it no grainings show through on the rocks or the foreground and, more convincingly, no wavy lines can be discerned in the margin of the text, where the wash is extremely light. A few additional changes have been made in the coloring of the Mellon copy. The lock of hair that floats over the right-hand female’s lap in all other copies has been covered with wash and extra fibers have been inked and painted over it. More roots have been added, in ink and wash, to the right-hand side so that the whole design becomes more symmetrical. The sickle moon on Albion’s thigh has been rounded, and the sun’s face has been altered.

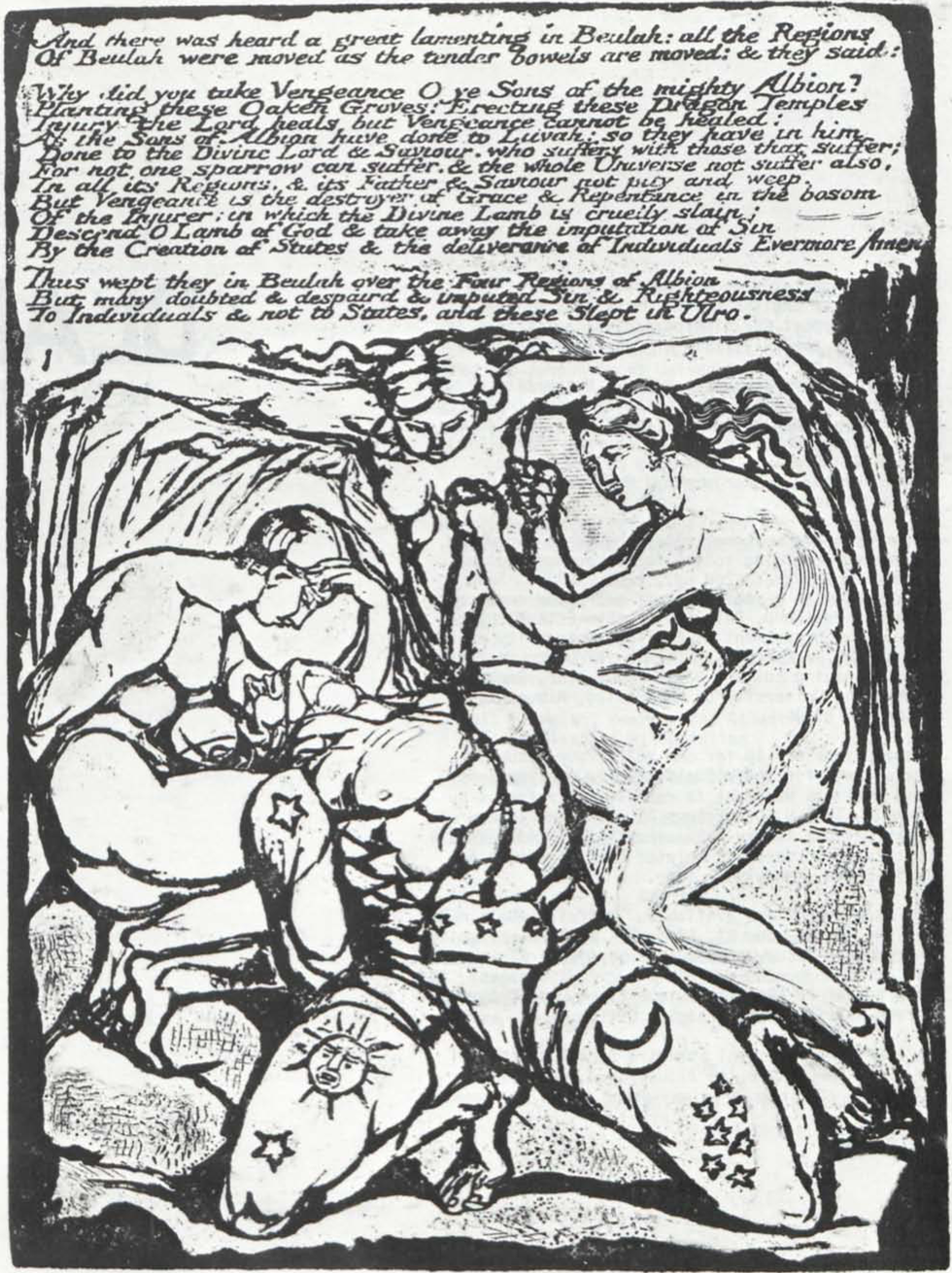

When Plate 25 in the Morgan copy [illus. 4] is examined it becomes clear that, after printing the Harvard and Mellon copies, Blake again altered his plate. The changes previously made have been carried further. The horizontal lines between the right-hand female’s head and hands have been extended so that they fill the whole of that space. Similar lines appear under the central female’s left hand and the lines above this hand have also been increased. The small wavy lines apparent in the second state to the right of the central female’s head have been elaborated so that they can be read as part of her hair. The stippling and cross-hatching on the rocks and the foreground have been greatly increased, and several small lines appear in the left-hand corner below the rocks. Again the figure most altered is the right-hand female. Muscular details have been added to her back, shoulder, thighs, calf and arm. Some delicate lines have been added around her eyes, forehead and nose. Her hair has also been altered, small wavy lines being noticeable in two of the floating locks nearest to her head and in the hair next to her face. These last alterations are interesting because they are clearly examples of white line engraving. The lines print white on the dark mass of hair. This is one of the few simple methods of altering a relief etching. Blake has simply cut into the relief mass of the design with a graver, and the lines, being incised, print white. The drapery that appears on the righthand female’s inner thigh is, I am reasonably sure, only an ink addition. A rudimentary form of this drapery appears etched, though faintly, in all copies, and is present in wash in the British Museum copy [illus. 1]. Another set of small lines has been added to Albion’s torso, this time lower down on his left side. This last change is anticipated by a wash shading in the British Museum copy. Curiously, in this state two of the Harvard changes disappear, namely the tears on the righthand female’s cheek and the central female’s pudendum [see illus. 2]. I shall return to this later.

The Fitzwilliam copy [illus. 5], despite certain differences, is, I think, in the same state as the Morgan copy [illus. 4]. The differences are not consistent with a change of state. The area of detail around the right-hand female’s eyes, which appeared for the first time in the Morgan, is missing. So is much of the finer detail on her back, shoulder, thighs, calf and neck, as well as the lock of hair in the small of her back. Some of the horizontal lines in the space between her and the central female and above the latter’s left hand are absent. There are three possible explanations for this anomaly. First, that there are four states and that the plate was again altered after the printing of the Morgan copy. Second, that the details not present in the Fitzwilliam were only ink additions to the Morgan copy. Third, that they were present on the plate when the Fitzwilliam was being printed, and that Tatham’s notoriously bad inking is to blame for their omission. The first explanation is the most unlikely. If Blake were going to alter a relief-etched plate—a complex operation—then it would seem likely that he would make a good many changes to justify his pains. This is true of the other two sets of changes. What is more, this would be a totally negative change of state. Blake would have removed details without adding others. This is again inconsistent with his previous behavior. This explanation can, I think, be dismissed. The missing details are either only ink additions, or they have been missed in the inking of the plate. At this point a close examination of the Fitzwilliam copy proves useful. If details were present on the plate but were missed in the inking then their impression could be visible on the paper. In Plate 21 of the Fitzwilliam copy many details present in the Harvard copy are missing but their imprint on the paper is clear, especially that of the ragged cloud. This tends to support the bad inking theory. When Plate 25 in the Fitzwilliam copy is examined it becomes clear that, not only is it messily and unevenly inked with a good deal of smearing, but that some parts of the design have been missed entirely. The lines above the central female’s right hand are only half printed, and so are the lines in the space between the two figures. The impression is there but the ink is so badly applied that only a smeared outline is printed. In other places there is no trace whatsoever of ink, yet the impression of the metal on the paper is clear. This is true of the missing details on the body of the righthand female, particularly those on her thighs and jaw. Some of the detail around her eyes is, I think, faintly visible as a blank imprint. The greater part of the missing detail can thus be safely ascribed to bad inking. However, one of the most cogent arguments against the Fitzwilliam printing’s being an accurate representation of the final state of Blake’s plate is aesthetic. The Fitzwilliam Plate 25 [illus. 5] is ugly and unpleasing. One can hardly imagine that Blake could ever have produced such an unbalanced design, in which the heavy work on the rocks is at odds with the lack of detail in the upper part.

begin page 48 | ↑ back to topThe[e] other problem to be considered is that of the absence in the Morgan and Fitzwilliam copies of certain details present in the Harvard copy. These are the tears on the right-hand female’s cheek and the extra lock of hair in the small of her back, the central female’s pudendum and the extra lock of hair to the left of her head, and the line drawn across the square block of stone. Have these details been added to the plate and then removed or are they simply ink additions? This can only be decided by examining the Harvard copy itself. However, I would like to think that one detail, the pudendum, was etched rather than inked, for it shows Blake returning to his prototype, Rosso’s Tre Parche, in reworking the plate.

Blake’s two sets of changes follow much the same pattern and a consistent aim emerges from them. First there is a continual attempt to render the surface of the plate more interesting, hence the grainings on the rocks and the background hatchings. There is also a tendency towards decorative elaboration, hence the increase in the fibers and the reworking and elaboration of the hair. There is also a concern with anatomical detail, evident in the additions to the right-hand female. All these changes make for a more interesting and lively plate. Some of the changes relate to the Rosso design, for example the addition of fine horizontal lines to the background, and, of course, the questionable pudendum. The changes also help to make the plate more solid and intelligible; flesh is distinguished from stone, figures from background. Most of the changes are, as I have pointed out, formal. They do not in any way alter the iconographic content of the plate. Unfortunately, the only change that does in any way affect the content is one that disappears after the second state, namely the tears on the right-hand figure’s cheek. However, even if this is only an ink addition it is worth considering. The addition of the tears gives Plate 25 richer interpretative possibilities. In the Cunliffe copy the absence of the tears and the blood-red coloration of the fibers and entrailstring combine to present a scene of simply unqualified cruelty. In the Mellon copy the softer russet coloration of the fibers and the entrailstring and the clearly delineated tears on the disemboweler’s cheek qualify the cruelty with a suggestion of mourning.

The changes in the plate are important because they show Blake’s tendency towards elaboration and refinement in progressive copies of a single work, a tendency usually obvious in his illuminations, but here seen in his attitude toward the plate itself. Possibly, however, there would have been far fewer changes to the plate had all or nearly all of the copies of Jerusalem been colored. Then Blake’s refining tendencies would have expressed themselves in the illumination rather than in re-etching and re-engraving. I have, in the foregoing account, ignored the considerable problem of how these changes were effected on a relief-etched plate. Apart from the one example of white line engraving, none of Blake’s changes are technically comprehensible, as they appear in areas of the plate which have been etched away. The existence of the posthumous copies rules out the possibility of reversing the order of the series, so that Blake is wiping his plate of superfluous detail. The only other possibility that offers itself is the existence of a second plate.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]