NOTES

Blake, Linnell, & James Upton: An Engraving Brought to Light

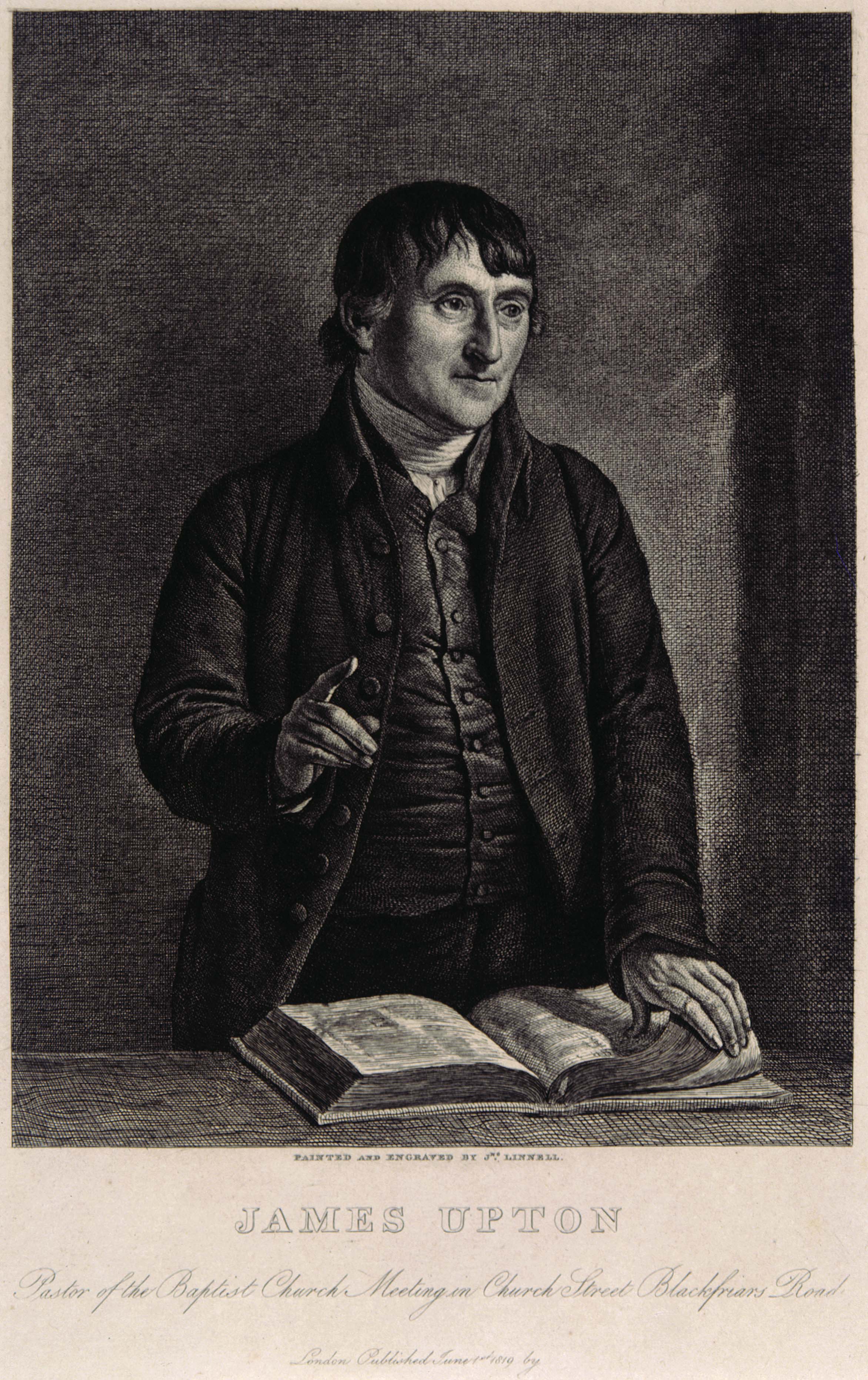

Shortly after their first meeting, John Linnell hired Blake to lay in an engraving after the younger artist’s oil portrait of the Baptist preacher James Upton (1760-1834). Linnell’s journal, account book, manuscript autobiography, and the miscellaneous Blake-Linnell accounts now at Yale and in Sir Geoffrey Keynes’ collection document this commission as thoroughly as any of Blake’s separate plates. We know when, for whom, and at what fee the work was done, but from 1912 until the present no one has actually seen the engraving and recognized it as in part Blake’s work. By a stroke of good fortune I was able to acquire two impressions of this plate—as far as I can determine, the only ones extant—in London during the summer of 1973. While it hardly embodies the energetic imagination found in Blake’s most admired engravings, it is a fine piece of craftsmanship with historical importance as the first product of Blake’s relationship with Linnell and as a strong influence on Blake’s later engraving style.

On 24 June 1818, Linnell wrote in his journal that he had gone “To Mr. Blake evening. Delivered to Mr Blake the picture of Mr Upton & the Copperplate to begin the engraving” (Bentley, Blake Records, p. 256). Years later, Linnell wrote about this same first employment of Blake in his manuscript “Autobiography”:

At Rathbone place 1818 my first Child Hannah was born Sep. 8, and here I first became acquainted with William Blake to whom I paid a visit in company with the younger Mr Cumberland. Blake lived then in South Molton St. Oxford St second floor. We soon became intimate & I employed him to help me with an engraving of my portrait of Mr Upton a Baptist preacher which he was glad to do having scarcely enough employment to live by at the prices he could obtain[;] everything in Art was at a low ebb then. (Blake Records, p. 257)With this modest endeavor Linnell began a friendship which was to sustain Blake throughout the last nine years of his life.

The sequence of payments for Blake’s work on the Upton plate is fully recorded in receipts made by both men. On 12 August 1818, Linnell paid Blake £2, and again on 11 September paid Blake another £5. The second payment is specifically entered for the “Plate of Mr Upton” in Linnell’s general account book (Blake Records, p. 584). Both payments are confirmed by Blake’s receipts, the second reading “Recievd 11 Septembr 1818 of Mr Linnell the Sum of Five pounds on account of Mr Uptons Plate” (Blake Records, p. 580). In his journal for 12 September, Linnell wrote that “Mr Blake brought a proof of Mr Uptons plate[,] left the plate & named £15 as the price of what was already done by him” (Blake Records, p. 258). Blake’s note of 19 September gives the full amount to be paid “For Laying in the Engraving of Mr Uptons portrait” as £15.15s., of which £7 had already been paid (on 12 August and 11 September). The outstanding £8.15s. was paid in two installments, £5 on 9 November and £3.15s. on 31 December (Blake Records, p. 581). Thus Blake worked on the plate from 24 June to 12 September 1818, and payment for his labors was completed on the last day of that year.

The earlier of the two impressions reproduced here [illus. 1] is a proof on India paper, laid on a sheet of unwatermarked white wove paper, lacking all letters except for “James Upton” very lightly scratched into the plate 1.8 cm. below the design. Most of the lines appear to have been engraved, although a few lines on the right margin have the blunt ends typical of etching. There was probably some initial etching of basic outlines, but this work has been covered by subsequent engraving. A. T. Story in The Life of John Linnell (London, 1892) notes that the plate was executed in part in dry point (II, 242), and this may well have been the method used to produce the fine lines in the face.

Just above the lower plate-mark is the date March. 1819— written in pencil, and to the right also in pencil is Unfinished Proof. must be returned to Mr. J. Linnell. This writing is very similar to the pencil notes on Fuseli’s drawings of Michelangelo and the frontispiece to Lavater’s Aphorisms once in Linnell’s collection which Ruthven Todd believes were “undoubtedly made by members of the Linnell family” (Blake Newsletter 19 [Winter 1971-72], p. 176). It seems likely therefore that the note on the Upton proof was begin page 76 | ↑ back to top

It is very difficult to determine the extent of Blake’s work on the plate. “Laying in” an engraving could mean anything from etching the bare outline to doing all but the finish work on the central figure. The amount which Blake requested for his work suggests that he did more than just outline etching. If indeed Blake’s financial situation was as tenuous as Linnell indicates in his “Autobiography,” then it would seem likely that Blake must have done considerable work on the copperplate to charge a new friend and potential patron £15.15s. The Hesiod illustrations executed in stippled lines after Flaxman’s designs brought Blake only £5.5s. for each plate in 1816. In 1824 and 1825 Linnell paid Blake £20 for his work on the portrait engraving of Wilson Lowery, and Blake’s contribution was in this case extensive enough for him to receive second billing on the plate (Drawn from Life by J. Linnell, & Engraved by J. Linnell & W. Blake). But it is unlikely that the first state reproduced here is the proof which Blake brought to Linnell on 12 September 1818. The six months between the delivery of the copperplate to Linnell and the pencil inscription on the India paper proof would have allowed Linnell to do a good deal of work on the plate. Further, had Blake almost finished the engraving himself, Linnell would surely have given him some recognition on the plate—or we would have a record of Blake’s reaction to such double-dealing and the entire Blake-Linnell relationship would not have been as fruitful as we know it to have been.

The Upton portrait marks an important watershed in Blake’s career as an engraver. Only the presentation of wood grain in the table seems characteristic of Blake’s earlier style, as in the “Beggar’s Opera” plate of 1788-90, the sixth illustration to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories (1791), and “Our End is come” (1793). Blake’s engraved portraits prior to and immediately following his contacts with Linnell demonstrate the influence that the Upton plate, and perhaps other engravings by Linnell, had on his craft. The profile of Lavater (1800) is a remarkably fine example of dot and lozenge engraving, but bears no resemblance to the Upton plate. In the portrait of Earl Spencer (1811), Blake returned to the techniques he learned in his youth from Basire. The engraving is burdened with a heavy net of lines unresponsive to differing textures, and although it does have a certain blunt power the total effect is unfortunate. In contrast, the Upton portrait is a first-class piece of work, with great subtlety in the handling of flesh tones and patterns of light and dark.

While nothing in Blake’s earlier work prepares us for the high-finish techniques of the Upton plate, Linnell’s own engraved portrait of Rev. John Martin, dated 1813 in the imprint, shows the same characteristics of modulated but basically dark ruled background, heavy cross-hatching on the clothing, and fine lines with dot and flick work on the hands and face. The same techniques appear again in Blake’s next engraving after the Upton plate, a portrait of Reverend Robert Hawker published by A. A. Paris in 1820. Although this plate reproduces a painting by Ponsford, not Linnell, the almost identical building up of the lines produces the same textures of cloth and skin, and even the same background shading, found in the Upton engraving. Clearly, Linnell’s techniques as an engraver embodied in the Upton plate, and perhaps in other examples seen by Blake, had a profound effect of Blake’s own methods. Even the Job illustrations show this influence, particularly in the use of swelling lines to delineate rounded forms, such as arms and legs, and in the dramatic use of light and shadow effects. The fine lines and dot and flick work used so effectively for the faces in the Job plates also owe a good deal to Linnell’s practice.

The sudden flowering of Blake’s late engraving style in the Job illustrations has never been explained. The Upton plate, regardless of the extent to which the work is by Blake or by Linnell, now makes the transition from the techniques of the 1790s to the Job less of a mystery. I would suggest that Blake’s reworking of “Joseph of Arimathea” and “Mirth” was also stimulated by his contacts with Linnell, although this theory would require dating the final state of the “Joseph” somewhat later than Keynes gives in his Separate Plates catalogue. The Job series—surely Blake’s masterpiece as an intaglio engraver—could not have been possible without Linnell’s financial assistance. With the rediscovery of the Upton plate it becomes clear that Linnell’s artistic influence was also crucial.