article

begin page 17 | ↑ back to topJames Smetham (1821-1889) and Gilchrist’s Life of Blake

begin page 18 | ↑ back to topJames Smetham’s claim on posterity has largely rested upon his 1869 review of Gilchrist’s Life of Blake which was incorporated in the second edition at Rossetti’s instigation. This sympathetic but conventional mid-Victorian interpretation of Blake only represents a minor aspect of Smetham’s career; his letters and paintings do far greater justice to the complexity of a man, whom Geoffrey Grigson has described as “an imaginative artist who surpasses almost all his time in England.”1↤ 1 G. Grigson, The Harp of Aeolus (London, 1948), pp. 96-97. This article will concentrate upon Smetham’s visual imagination seen in the light of the marginal illustrations with which he annotated his own copy of the Gilchrist Life.2↤ 2 Collection of Dr. Gerald Bindman.

An almost overwhelming degree of spirituality pervades Smetham’s small scale biblical and landscape compositions, which prompted Rossetti to invoke parallels with the work of Blake and Palmer: “In all these he partakes greatly of Blake’s immediate spirit, being also often allied by landscape intensity to Samuel Palmer.”3↤ 3 A. Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, 2nd ed. (London, 1880), p. 429. The emotional energy required to achieve such an effect, did, however, contain the seeds of self-destruction as

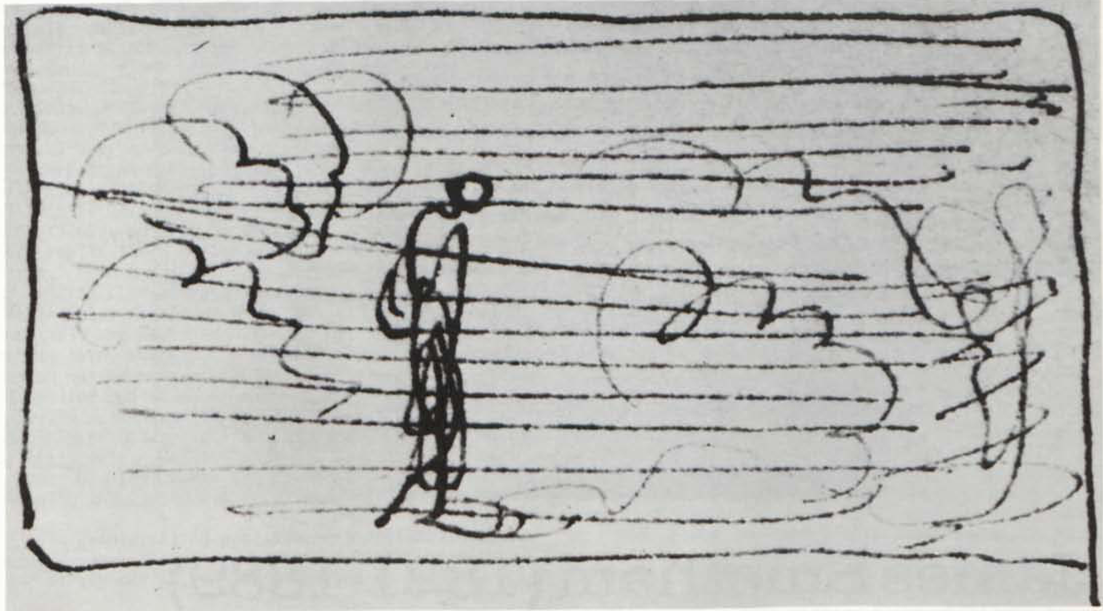

Ruskin prophesied in 1854,4↤ 4 J. Ruskin, Works, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (London, 1903-12), XIV, 461. and Smetham was eventually to subside into an endogenous depressive illness from 1878 until his death of 1889. The Smetham correspondence exhibits some of the same begin page 19 | ↑ back to top intimate, revelatory quality as the Haydon diaries,5↤ 5 J. Smetham, Letters, eds. W. Davies and Sarah Smetham (London, 1891). unfolding a personality which partook of “Blake’s immediate spirit” transmuted by a powerful strain of Methodist piety; this bifurcal influence clearly emerges in the unifying theme of the letters, Smetham’s concept of destiny in terms of a Pilgrim’s Progress which, in visual form, was poignantly summarized by one of his last paintings, Going Home, depicting an old man on the road to death.6↤ 6 Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Smetham’s endeavor to develop a fully integrated imagination combining “art, literature and the religious life all in one,”7↤ 7 Smetham, Letters, p. 13. was reflected in a self-imposed regime of intense, disciplined study, the results of which were enshrined in a system of monumentalism; the grandiose designation of monument was in fact applied to a tiny, squared pen drawing, encapsulating in the margin Smetham’s thoughts on the text in question. Shakespeare, the Bible, Tennyson and Gilchrist’s Life of Blake were all subjected to this approach, which was initiated by the artist at eleven o’clock on the evening of 18 February 1848. The creative fervor and elevation of purpose infusing the thumbnail sketches, is eloquently expressed by Smetham’s account of how, in later years, he would revisit his monuments, “pouring the oil of joy on the shapeless stone in which I saw my thought as Michael Angelo in his marble saw hidden the gigantic shapes of Night and Day.”8↤ 8 Smetham, Letters, p. 92.Smetham’s copy of Gilchrist is a peculiarly apt example of monumentalism since he had been recommended by Rossetti in 1861 as a suitable draughtsman for the line drawings in the text. In the event Smetham was deprived of the commission but in July 1867 supplied his own miniature cycle of the life of Blake, which paid a self-conscious

![ÆT[ATIS] 26.]

STRUGGLE AND SORROW.

55

of the same suggestive theme, is Let loose the Dogs of War—a

Demon cheering on blood-hounds who seize a man by the throat;

of which Mr. Ruskin possesses the original pencil sketch, Mr. Linnell

the water-colour drawing.

1784

S[u]nd[a]y July .4. Ja[me]s B[lake]

During the summer of 1784, died Blake’s father, an honest

shopkeeper of the old school, and a devout man—a dissenter. He

was buried in Bunhill Fields, on the fourth of July (a Sunday) says

the Register. The eldest son, James,—a year and a half William’s

senior,—continued to live with the widow Catherine, and succeeded

Catherine

W[illiam] B[lake]

Rob[er]t

to the hosier’s business in Broad Street, still a highly respectable

street, and a good one for trade, as it and the whole neighbourhood

continued until the era of Nash and the ‘first gentleman in

Nash.

Europe.’ Golden Square was still the ‘town residence’ of some

half-dozen M.P.’s—for county or rotten borough; Poland Street and

Great Marlborough Street of others. Between this brother and the

artist no strong sympathy existed, little community of sentiment

or common ground (mentally) of any kind; although indeed, James

— for the most part an humble matter-of-fact man—had his spiritual

and visionary side too; would at times talk Swedenborg, talk of

seeing Abraham and Moses, and to outsiders seem like his gifted

brother ‘a bit mad’—a mild madman instead of a wild and stormy.

Ja[me]s B[lake]

On his father’s death, Blake, who found Design yield no income,

Engraving but a scanty one, returned from Green Street, Leicester

Fields, to familiar Broad Street. At No. 27, next door to his brother’s,

he set up shop as printseller and engraver, in partnership with a

former fellow-apprentice at Basire’s: James Parker, a man some six

or seven years his senior. An engraving by Blake after Stothard,

27. Ja[me]s Parker. 34

W[illiam] B[lake]

Zephyrus and Flora (a long oval), was published by the firm ‘Parker

and Blake’ this same year (1784). Mrs. Mathew, still friendly and

patronizing, though one day to be less eager for the poet’s services

as Lion in Rathbone Place, countenanced, nay perhaps first set the

scheme going—in an ill-advised philanthropic hour; favouring it,

Zeph[yru]s & Flora.](img/illustrations/StruggleAndSorrow.8.1-2.bqscan.png)

![and

[cheris]hed

[blen]ded

[be]fore

[techn]ical

[desi]gn.

[half-a-cro]wn,

[1]0d.

[n]ew](img/illustrations/Robert.8.1-2.bqscan.png)

![Is[aiah]

Ezek[iel]

[H]ELL. 83](img/illustrations/IsaiahAndEzekiel.8.1-2.bqscan.png)

![[Ang]el;

[weste]rly

[Th]en

I

[volum]es,

[ca]me

[betw]een](img/illustrations/Saturn.8.1-2.bqscan.png)

![Godwin. Fuseli

H[olcroft]

Price Priestley Blake](img/illustrations/Johnson.8.1-2.bqscan.png)