review

Anne Kostelanetz Mellor. Blake’s Human Form Divine. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974. Pp. 354, 87 illus. $15.

Since the appearance of Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic in 1970 almost every new study of Blake has paid at least lip service to the goal of unifying his “composite art.” Ms. Mellor’s contribution to this task is a comprehensive study of “form” in Blake’s work, touching upon almost all of the illuminated books and detouring into some of the Milton illustrations, the Book of Job, the Arlington Court Picture, and the Bible paintings. The student who is looking for close readings of individual poems or pictures, or for new information on iconography and verbal symbolism will not find these things here. What he will find is best summed up in Ms. Mellor’s introductory remarks:

This study of Blake’s visual-verbal art will focus upon the development of form in his work, both as a philosophical concept and as a stylistic principle. I have chosen to emphasize this aspect of Blake’s art, which has not been previously examined at length, because the functions and purposes of form came to pose a critical problem for Blake’s thought and art. I hope to show that in 1795, Blake was simultaneously rejecting as a Urizenic tyranny the outline or “bound or outward circumference” which reason and the human body impose upon man’s potential divinity and at the same time creating a visual art that relied almost exclusively upon outline and tectonic means. (p. xv)

There is some exaggeration in the statement that this subject has not been previously examined at length (most of the studies of Blake in the last twenty years have addressed themselves to the question of form in one sense or another), and there is a misleadingly cautious note in Ms. Mellor’s restriction of her hypothesis to 1795, since the book really offers a developmental scheme which covers Blake’s entire artistic career. Nevertheless, this year is the keystone in Ms. Mellor’s argument. Blake is seen as moving from a period of utopian optimism and harmony between his formal theories and stylistic practice, to a middle period (centered in 1795) of antiutopian pessimism and conflict between theory and practice, to a final period of return to “the beliefs Blake held as a young man” (p. 215).

The dates of these periods are treated rather flexibly. The middle period is centered in 1795, but its emergence is located “between 1790 and 1795” (p. xvi), and the real watershed sometimes appears to be 1793-94, when Blake allegedly abandons the optimism of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell for the pessimism of the late Lambeth books. This period is described as continuing on from 1795 to 1802 (p. 193), but Ms. Mellor appears to have in mind a transition period from 1802 to 1805 (Blake’s final years at Felpham and his return to London), which ushers in the final period, 1805-27 (p. 243). The periods indicated in Ms. Mellor’s chapter titles do not correspond very clearly to the developmental scheme presented in the text: Chapter 4, “Romantic Classicism and Blake’s Art, 1773-1795,” does not mean that his style of “Romantic Classicism” ended in 1795 (Ms. Mellor argues that it continues throughout his career); Chapter 5 deals with “Blake’s Concept of Form, 1795-1810,” but this “period” is operative only in the discussion of Vala; elsewhere, Blake’s “late art” is located from 1805 to 1827.

A three-phase notion of Blake’s development is fairly commonplace (E. D. Hirsch has presented the most radical argument for it in his Innocence and Experience: An Introduction to Blake, New Haven, 1964), and probably has a general kind of validity. It seems likely that Blake underwent some sort of personal crisis after the failure of the French Revolution, and another during his sojourn with Hayley in Felpham. In her “Note on Methodology” Ms. Mellor links her views with what she calls the “chronological approach” exemplified by David Erdman, Morton Paley, and Sir Anthony Blunt (one wonders why Hirsch is not mentioned here). This approach is contrasted with that of the “system” critics, Robert Gleckner and Northrop Frye, who tend to see Blake’s work as a continuous, coherent whole. In some ways this methodological dispute seems to me a dead issue (especially if it means I have to decide whether to believe David Erdman or Northrop Frye); if not dead, it should be laid to rest with all deliberate speed. I doubt that Northrop Frye would be insensible to Ms. Mellor’s contention that “Blake was, after all, a human being, subject to the same changes of heart and mind that plague and enrich us all” (p. xix).

The real questions of interest are, of course, whether and how these changes are manifested in Blake’s work, and whether and how they affect our interpretations of those works. The answers to these questions seem to me equivocal. The scheme of optimism-pessimism-optimism may have validity of a sort, but I find it hard to see Blake so utterly depressed for all those years, even if he was illustrating Young’s Night Thoughts. Blake’s remark in 1804 about being “enlightened with the light I enjoyed in my youth, and which has for exactly twenty years been closed from me” cannot be taken at face value (are Songs of Innocence and begin page 118 | ↑ back to top The Marriage of Heaven and Hell the works of a man who had lost the light of his youth?). If the statement is used to prove anything about Blake’s development (as Ms. Mellor uses it on page 202), then we must conclude that Blake’s pessimistic period extends from 1784, not 1794.

The main evidence for Ms. Mellor’s argument is what she sees as the “anti-utopian” character of the late Lambeth books and the 1795 color prints. The Book of Urizen, The Book of Los, Ahania, and Europe mark a period when Blake “condemns the human body and all limited, rational, abstract systems” (p. 139). While it is true that these poems are generally more sombre and inconclusive than some earlier works (except Tiriel, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and many of The Songs of Experience), it is quite easy to find Blake “condemning” the human body, reason, and limits in many of his pre-1794 writings. As early as 1788 he attributes religious divisions to “the confined nature of bodily sensation,” asserts that “the bounded is loathed by its possessor,” and satirizes rationalism and empiricism (see There is No Natural Religion, both versions, and All Religions Are One). It is also possible to see him making a distinction in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell between a true reason which serves as “the bound or outward circumference of Energy,” thus functioning as a “Contrary” to Energy in order to produce “progression,” and a false reason which usurps the role of energy and tries to dominate human consciousness. There is also a related distinction to be seen between a false body which confines the soul entirely within the realm of the five senses, and a true body which serves as a medium for the infinite “by an improvement of sensual enjoyment” (MHH 3, 4, and 14). Ms. Mellor seems to recognize this dialectical role of reason, and the visionary role of the body, but she argues that, within a year of articulating these distinctions in The Marriage Blake had changed his mind: “Whereas Blake had earlier defined the body as ‘a portion of Soul discern’d by the five senses’ [MHH 4], he now pictures the body as fixed, finite matter inexorably bounded by the five senses and the circumscribing force of reason” (p. 94). The difference from the 1788-1793 period seems to be encapsulated in the word “inexorably,” i.e., “incapable of movement or change.” Hence, the conclusion: “man must deny his mortal body to enter heaven” and “only death can save man from the problem of human evil” (p. 100).

Ms. Mellor makes no mention of the fact that Europe opens with one of Blake’s most eloquent assertions of the power of the senses to discern at least a portion of the infinite:

Five windows light the cavern’d Man; thro’ one he breathes the air;The body is a cave in Europe, as it was in The Marriage, where “man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern” (MHH 14), but it still has windows and “doors of perception” which can be cleansed to reveal the infinite. There is nothing “inexorable” about this image of confinement.

Thro’ one, hears music of the spheres; thro’ one, the eternal vine

Flourishes, that he may receive the grapes; tho’ one can look.

And see small portions of the eternal world that ever groweth;

Ms. Mellor cites another passage from Europe to show the “body as a physical prison that confines and inevitably prevents Energy from expanding into infinity” (p. 99):

. . . when the five senses whelm’dBut this passage really says just the opposite of what Ms. Mellor claims: the body is seen here, not as a prison which confines energy, but as a bastion against the chaos of rational empiricism. The body is the Noah’s Ark which rescues man from the “cold floods of abstraction” that engulf Europe.

In deluge o’er the earth-born man; then turn’d the fluxile eyes

Into two stationary orbs, concentrating all things

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Into earths rolling in circles of space, that like an ocean rush’d

And overwhelmed all except this finite wall of flesh.

Ms. Mellor seems unaware of or indifferent to the counter-evidence to her assertions, and she never deals with any alternative hypotheses that might explain the evidence more fully. She ignores the argument, for instance, that Blake might be presenting the body as a cave or prison in the Lambeth books, not because he is “rejecting” the body (or reason or boundaries) per se as “inevitably” oppressive, but because he is concerned with the question of how, in fact, the true body of “sensual enjoyment” and delight comes to be replaced by a false body which confines the spirit. The answer to this question would be, for Blake, the abuse of reason—not the right reason which is an eternal contrary to energy, not the reason which “A Little Boy Lost” uses to expose the priest’s mysteries, and not the reason which Tom Paine uses to expose Bishop Watson—but the false reason which tries to impose one abstract law on life, or reduce human experience to a “Ratio of the Five Senses.” The late Lambeth books deal with the linked themes of fall and creation, the fall of reason into a void of abstraction, and the creation of a body as an (admittedly imperfect) barrier against nihilism, the “ocean of voidness unfathomable” (Urizen 5: 10). They do not spell out any redemption or apocalyptic awakening—in Faulkner’s terms, Blake was probably more concerned with surviving than prevailing in 1794. But there is nothing “inexorable” or “inevitable” about them: they are open-ended poems, the Genesis phase in Blake’s “Bible of Hell,” as the title of The [First] Book of Urizen implies.

The overall problem with Ms. Mellor’s approach is revealed in her remarks on how she dealt with the editorial problems in Vala: “I . . . have often, I fear, chosen that arrangement of text that most clearly reveals the theme with which I am primarily concerned.” In a similar way, she begin page 119 | ↑ back to top mobilizes textual evidence, frequently misinterpreted, from Blake’s earlier writings, not to explain those works, but to demonstrate her hypothesis about his development. This sort of strategy can only confuse and mislead the beginning student of Blake, and it will certainly fail to convince the experts.

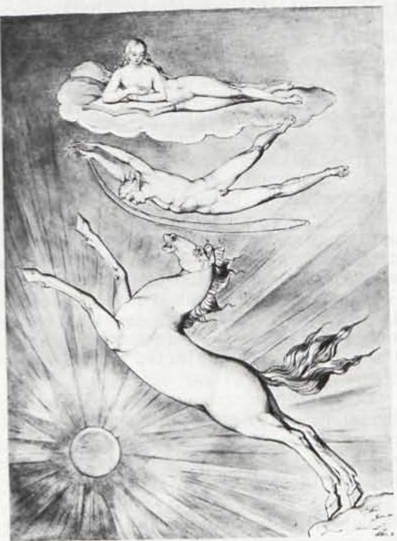

But suppose, for the moment, that Ms. Mellor’s hypothesis were true, and that Blake did go through a loss of faith in the middle of his career, a period in which the body, reason, the material world all seemed utterly unredeemable. How would this affect his art or our response to it? Ms. Mellor’s answer is very surprising and paradoxical. It turns out that Blake’s supposed hatred of bodies and boundaries has no effect whatever on his pictorial strategy: “here, as everywhere, the heroic human form dominates Blake’s mature art” (p. 138). The linear, tectonic, non-illusionistic style of “Romantic Classicism” remains constant throughout Blake’s work, and the human figure is never more glorious than in the pictures done at the height of Blake’s supposed pessimism about the body, the 1795 color prints.

If Blake’s alleged hatred of bodies and boundaries had no discernible effect on his pictorial style, then the only thing left for it to do is to affect our response to that style, to make us perceive contradictions between what Blake is supposedly trying to say and what he actually does say in his pictures. It permits us, in other words, to patronize Blake retroactively, and to say things like “Blake was of the human body’s party without knowing it” (p. 164).

There is, however, a kernel of truth in Ms. Mellor’s intuition of a paradox in the Lambeth books. She is right to notice a tension between Blake’s poetical “condemnation” of Newton and his depiction of him as a magnificent nude. Blake does, as she notes, use “the same visual style and media to paint both evil and good images,” and thus “his normative attitudes often blur” (p. 139). But this paradox is not a result of unconscious contradictions: it is all of a piece with Blake’s explicit strategy of satirizing categories of good and evil, as described in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Newton and Urizen may be in error, but they are never defined as evil, utterly cast out, unredeemable. Their heroic potential continues to shine, even in the darkest pictures, and the “unsuspecting physicists” who use the Newton print to “illustrate their textbooks” (p. 164) have, in this case, more insight into Blake than Ms. Mellor.

There are some good things in this book, cropping up when Ms. Mellor forgets about demonstrating her paradoxical hypotheses. Her discussion of the relation between Innocence and Energy (Chapter 3) establishes a bit of continuity and coherence in Blake’s thought that is sometimes overlooked. Her analyses of the illustrations to L’Allegro and Il Penseroso and the Arlington Court Picture (Chapter 7) challenge previous readings in interesting ways. But the general tendency of the book is to exaggerate and falsify for the sake of the thesis. In The Ancient of Days engraving, we are told, “Blake has totally rejected

a natural space” (p. 136). Why, then, did he make those shapes remind us of a sun breaking through clouds? “Blake’s nudes,” we are told, “are always in motion, never static” (p. 144), except, presumably, about three-fourths of the time. Only while revising The Four Zoas from 1805 to 1810 did Blake learn that “the fall may be psychological rather than physical” (p. 206), a statement which leaves us wondering what those “mind-forged manacles” of “London” (1794) were made of!I will not go into the numerous problems which arise from Ms. Mellor’s fuzzy use of previous criticism, particularly her adoption of the concepts of “closed” and “open” form, taken from Heinrich Wőlfflin’s distinctions between Renaissance and Baroque art. Suffice it to say that Ms. Mellor seems unaware(1) that Wőlfflin’s categories have been vigorously challenged as over-simple by art historians;(2) that there might be problems involved in transferring concepts developed to distinguish two historical epochs onto the work of a single artist;(3) that she has reduced Wőlfflin’s subtle refinements of the concepts of open-ness and closure to his remarks on geometry, and that Wőlfflin would certainly have seen all of Blake’s paintings as “closed” in his terms.

It is distressing not to be able to find more good things to say about this book. Ms. Mellor’s general intuitions seem quite good: her interest in form in a developmental context, her emphasis on checking Blake’s aesthetic theory against his practice, her use of stylistics in harness with iconography—all these are, to my mind, exactly the kind of approaches that need to be applied to Blake’s art. Unhappily, they do not take us very far in this particular book, and the reader who wishes to learn about Blake through Ms. Mellor will have to sift through a great deal of chaff before discovering the wheat.