REVIEWS

The Mental Traveller, a dance-drama based on the ballad by William Blake. Presented 19 August-7 September 1974, Crown Theatre, Hill Place, Edinburgh. Cast: Heidi Parisi and Neil Tennant. Lights: Sonia Mez. Score: Wanda Laukenner. Sound: Cameron Crosby. Choreography: Heidi Parisi and Neil Tennant.[e] Director: Heidi Parisi. Producer: The Oothoon Dance Theatre in association with the Edinburgh University Theatre Company. Costumes: Megan Tennant.

In his engraved work Blake addressed himself to “the intellectual powers,” which means he intended his work to be not just an aesthetic treat for the eye and the ear, but a total communication from mind to mind through many senses at once. Since Blake’s time the graphic arts have followed many programs less synaesthetically complete than this; but one art form, the ballet, has preserved the fullness of Blake’s vision. Of all the arts of the twentieth century, it is the ballet which “unites music and drama on their common basis in the dance, just as the Job engravings unite poetry and painting on their common basis in hieroglyphic, and it can hardly be an accident that Blake’s vision of Job makes an excellent ballet.”1↤ 1 Frye, Fearful Symmetry (Princeton, 1947), p. 417. “The Sick Rose” has also been successfully choreographed, and following the lead established by these adaptations of Blake’s art to dance, the Oothoon Dance Theatre presented “The Mental

begin page 129 | ↑ back to top Traveller” at the Edinburgh International Festival Fringe in 1974 to a warm reception by the critics.2↤ 2 See reviews by Nicholas Dromgoole, in The Sunday Telegraph, 1 Sept. 1974; Una Flett, in The Scotsman, 26 Aug. 1974; and Fernau Hall, in The Daily Telegraph, 20 Aug, 1974.Of all Blake’s works, one might ask, why choose “The Mental Traveller”? With an unlimited budget and an audience of perpetual insomniacs, the company might have been able to mount a production of one of the prophetic books. But without either of these, some compromises had to be made. The problem was to determine which of Blake’s shorter works would lend itself to the dramatic and symbolic expression of the choreographer, and at the same time not become too allusive for a general audience. “Mad Song, ” The Book of Thel, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, The Gates of Paradise, and “The Crystal Cabinet” were all considered for a time, but “The Mental Traveller” was eventually chosen because it too contains the familiar cycle in the fallen world, which, though it turns through many of the same phases Blake described in his engraved works, yet moves to a simpler and more ordered cadence. The poem relies more on event than on dialogue, character, or conceit, thus easing the translation from verse into dance. In addition, since the poem was never engraved, the choreographer is not bound to literal fidelity in illustrating a particular line or stanza. With “The Mental Traveller,” instead of probing into the lengthy cadences, the catalogues, digressions, and in general the epic sweep of the prophetic books, one simply submits to the brevity and honesty of the ballad form. Yet within this short and conventional poem, Blake’s life-long concern with perception and human desire still commands one’s attention.

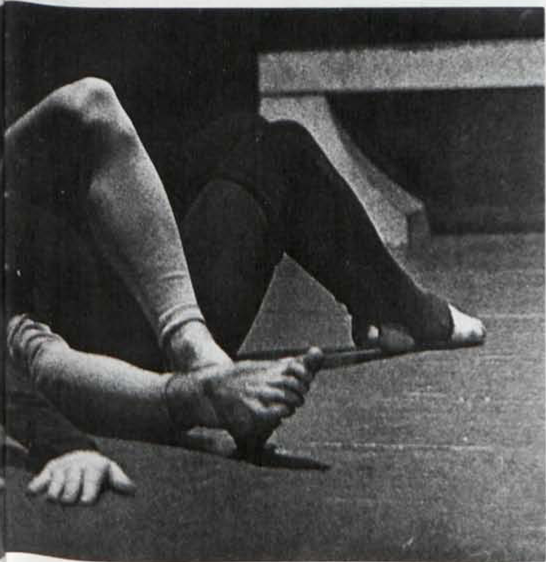

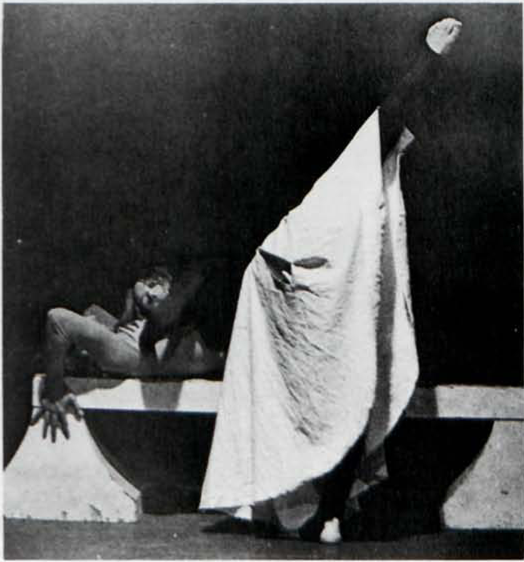

All the characters in the poem were portrayed by two dancers, Heidi Parisi and Neil Tennant. In their interpretation the poem was seen to embody a struggle between male and female, each longing for the other and soon swept away by desire itself. A viable relation never develops between the two sexes, for one of them always begins to eye the other with relish, devising ways to enjoy the other. In seeking the other, each sex mistakes possession for love; and in possessing the other, each becomes a hideous monster devouring an unrecognizable victim (illus. 1). During these transformations, which were quite sharply pointed in the production, the audience was given the chance to see that while the poem seems to tell of birth, growth, and change, all of these end in a reversion to barbarity (illus. 2).

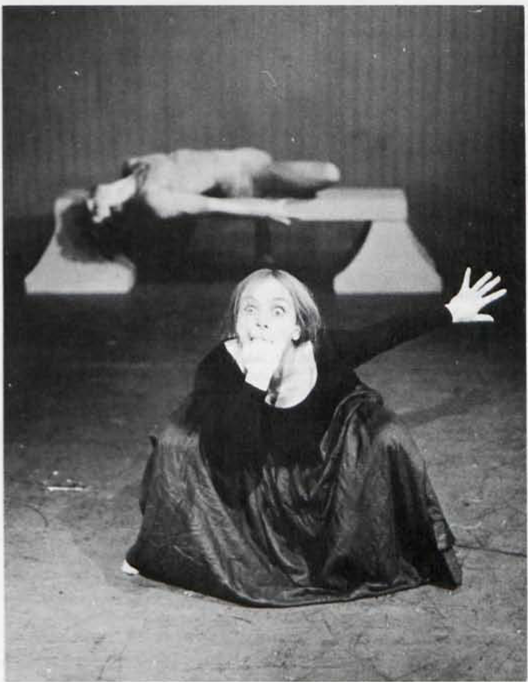

This schematic interpretation simplified many complicated passages in the poem, and confined the drama to a field somewhere between the two fixed poles of innocence and wrath. In the brief intervals between the portrayal of innocence and its domination by wrath, the stage was blacked out. To portray the innocence of the maiden in lines 57-64, Ms. Parisi used the postures of the human marygold in plate iii of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, of the child in the Frontispiece to Songs of Innocence, and

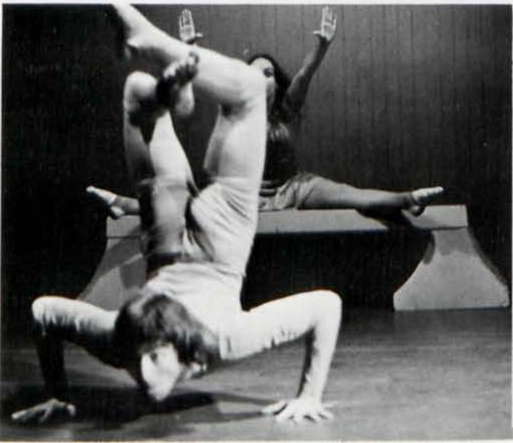

begin page 130 | ↑ back to top of the spritely figures dancing in flames in “The Blossom.” To portray wrath and its megalomania, Mr. Tennant made repeated use of the tormented facial expressions of the characters in plate i of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; plates i, 1, and 4 of America; plates 2, 3, and 4 of The Gates of Paradise; plates 4, 7, 11, 14, 19, and 22 of The First Book of Urizen; and plates 37 [41] and 51 of Jerusalem. Some commentators mistakenly referred to the production as a ballet, but the leaps of Ms. Parisi in her portrayal of the maiden, and the expressions of Mr. Tennant in his portrayal of the old man, as well as a number of other details, should establish it as modern dance.More precisely, one may distinguish it as a specific kind of modern dance, one based on Blake’s iconography. The differences are crucial. While all dance relies on firm control of the lower back, the classical, conservative type of ballet performed, for example, by the Royal Ballet, uses the lower back largely for support, so that formal beauty can be achieved by the elongation of line in the extremities of the body (illus. 3). The legs and the arms, and the manner of their movement attract more interest than posture, which is uniformly correct in any case. In the Graham technique of modern dance, on the other hand, the torso remains the base of movement and energy, as well as the center of attention; and energy which extends into the arms and legs can only derive from the torso. The type of ‘dance’ Blake created in his art appears to be much closer to modern dance than to ballet in this respect. Blake’s dance is based on outline and continually underscores the importance of boundaries. The shape of the body and the way it defines space are more important than the parts of the body; and while “the hands and the feet” are no less important than “the lineaments of the countenances,” both are subservient to overall form, which can only be distinguished by outline (illus. 4). Whereas in ballet the torso remains upright while the legs plié, in preparation to sauté or relevé, for instance, in modern dance the pelvis contracts by tilting, and the torso twists and coils as the dancer focuses his energy for release into another movement. Whereas in classical ballet the dignified, vertical body is the standard behind which decorum is never violated, and a mode of expression is prescribed for every conceivable maneuver, in modern dance the body may grovel or crawl in abandon, or even turn belly up in defiance of the vanities of taste. Without the weight of a long tradition, and with fewer necessary idioms, modern dance can accommodate the grotesque as well as the sublime, the pathetic, and the

begin page 131 | ↑ back to top beautiful in the same mode. So too, in dance based on Blake, levels of style do not have to be discrete. A figure can be heroic and satiric at the same time, or sublime and demonic. The counterpart of the pilé in ballet and the contraction in modern dance is the low solidified crouch in Blake (as in plate 37 of Jerusalem), in which energy is first compressed to “the limit of contraction” before it can be released outward into a complete and meaningful movement. This posture, of despair, symbolizes the most unfortunate and painful condition one can suffer, and its place in Blake’s dance as the primary posture should come as no surprise when one recalls Milton’s assertion in Aereopagitica that evil is the primary condition of man in this world, where we all must suffer “that doom which Adam fell into of knowing good and evill, that is to say of knowing good by evill.”While Blake’s dance is more closely allied to modern dance than to ballet, it is distinguished from both of these by its own set of characteristics. Perhaps the greatest distinction is to be found in the area of meaning. In both ballet and modern dance, any movement—an arabesque, for instance—can be given an almost unlimited range of meanings. The choreographer can alter head, arms, or legs to any angle, depending on what he wishes to convey. The arabesque alone, without context, has no prescribed meaning, and invokes no necessary response from the audience. But Blake’s postures, despite critical controversy as to their exact meaning, at least have the distinction of a specific, predicated meaning, both generically, and in specific contexts. None of Blake’s postures is merely “expressive.” On the contrary, each is articulate and definitive. Each posture, like each image, illuminates a conception in Blake’s moral allegory, and all of these are capable of being precisely stated. The severe crouch, for instance, the crowding of mad Tom in “Mad Song,” can only indicate despair and melancholy,3↤ 3 See Janet Warner, “Blake’s Figures of Despair: Man in his Spectre’s Power,” in William Blake: Essays in Honour of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, ed. Morton Paley and Michael Phillips (Oxford, 1974). so that the man who exists in this state becomes despair itself. Blake’s postures and gestures are, therefore, not steps as in the repertory of ballet and modern dance, but symbols.

We know that Blake’s symbolic postures derive largely from the allegorical figures in Medieval and Renaissance art, and we also know that Blake was attracted to this material partly because it seemed to coincide with the recently revived (though no less fanciful) notion of the “hieroglyphick.” Now despite the fact that there never was a language of “hieroglyphicks,” inherited from prelapsarian Adam, codified by the Egyptians, turned to parables by the Jews, and diluted into rational discourse by the Romans, Blake was nevertheless able to create a viable “alphabet of human forms” based on what he assumed this primeval language must have been. Between Blake’s two extremes of the catatonic collapse of humanity, as depicted in plate 37 of Jerusalem, and humanity fulfilled and beatific, as depicted in “Albion rose,” there are a thousand other postures of every attitude and variation. When one sees a group of these presented dramatically, it is

possible to glimpse an underlying structure in the plenitude of forms. In the production of “The Mental Traveller” the alphabet of human forms was visible not only in the phrasing of the dance, which accentuated particular postures from Blake, but also in the cumulative effect of so doing. In scene three, for instance, which depicted the old woman cutting “his heart out at his side,” Ms. Parisi moved in turn through the postures of Vala, Rahab, and Tirzah from plate 25 of Jerusalem. And in scene four, which depicted the boy struggling to “rend up his manacles,” Mr. Tennant moved in turn through the postures of Bromion and Theotormon from the frontispiece to Vision of the Daughters of Albion, the tortured pose of Urizen from plate 22 of The First Book of Urizen, and the even more pressing agony depicted in plate 7 of Urizen. In order to phrase these passages adequately—that is, to dance through the poses rather than simply present a dumb show—both dancers had to assume a whole range of intermediate postures interpolated from Blake. Expanding the cardinal points of the dance in this manner supplied a certain euphony and momentum which cemented one’s memory of Blake’s separate images into a single, seamless story, which, it seemed, could only derive from a single, consistent alphabet. begin page 132 | ↑ back to topIf future choreographers follow leads of this kind, dance will surely attract more attention in the study of Blake.4↤ 4 See Erdman, “The Steps (of Dance and Stone) That Order Blake’s Milton,” Blake Studies, 6 (Fall, 1973), 73-87. Indeed, in adapting Blake’s art for dance, the dancers may have been approaching William’s (and Catherine’s) own method of composition—that is, composing directly with the body rather than copying from the antique or from models. As some of Erdman’s students know, working out Blake’s postures with one’s own body is a valuable heuristic tool capable of revealing meanings which scholarly scrutiny has been at pains to discover.

In this production of “The Mental Traveller” there was perhaps only one significant departure from current interpretations,5↤ 5 See, for instance, James Sutherland, “Blake’s ‘Mental Traveller,’” ELH, XXII (1955); Harold Bloom, Blake’s Apocalypse, (New York, 1963); Northrop Frye, “The Keys of the Gates,” in Some English Romantics, ed. James V. Logan, John E. Jordan, and Northrop Frye (Columbus, 1966); and E. J. Rose, “Los, Pilgrim of Eternity,” in Blake’s Sublime Allegory, ed. Stuart Curran and Joseph A. Wittteich, Jr., (Madison, 1974). and this because a dramatic presentation required the tone to be fixed unambiguously from the outset. The character of the traveller-narrator was seen not as one of the Eternals, nor as the boy himself, nor as William Blake the poet, but rather as someone who could only be describing events in which he took a part. Like the Ancient Mariner, he would not have gathered his information from hearsay. The tale which begins with the old woman torturing and killing the young boy must be the story of the traveller’s own struggle for life and salvation. Thus the traveller himself must embody the entire cycle with its repeated failures and tyrannies. The figure with the most appropriate appearance for this task, and the one which also be recognizable to the audience—remember, the traveller has only a tiny part in the drama itself—was Death or the Angel of Death. This gruesome character, with an ashen face the tone of gunmetal, and wearing a black swallowtail coat and a wide black raven’s-wing hat, entered the stage in semi-darkness to tell his tale. While he lingered silently, the audience noticed a smooth, pink bundle under his coat, a child of three months. As the traveller began his journey off the stage, a malicious crone strode venomously forward, and the traveller’s tale unfolded according to the following scenario.

SCENARIO

Act One

| Lines | Scene | Score |

| 1- 8 | One | Zoltán Kodály, Serenade for Two Violins and Viola. Second Movement. |

| 9-12 | Two | Béla Bartók, Hungarian Folksong. |

| 13-19 | Three | Sergei Prokofiev, Sonata Number Six. First Movement. |

| 20-22 | Four | Samuel Barber, Sonata. Opus Twenty-six. |

| 23-28 | Five | Charles Ives, String Quartet Number Two. Second Movement. |

Act Two

| 29-36 | One | Béla Bartók, Strings, Percussion and Celeste. Third Movement. |

| 37-42 | Two | Sergei Prokofiev, Sonata Number Six. Final Movement. |

| 43-52 | Three | Arnold Schoenberg,[e] March from Serenade. Opus Twenty-four. |

Act Three

| 53-56 | One | Hugo Wolf, Das Spanische Liederbuch. Fourth Song |

| 57-64 | Two | Béla Bartók, String Quartet Number Four. Fourth Movement. |

| 65-85 | Three | Béla Bartók, String Quartet Number Four. Last Movement. |

| 86-88 | Four | Béla Bartók, Strings, Percussion and Celeste. Third Movement. |

| 89-92 | Five | Béla Bartók, Sonatina. First Movement. |

| 93-103 | Six | Béla Bartók, Hungarian Folksong. |

| 104 | Seven | Zoltán Kodály, Serenade for Two Violins and Viola. Second Movement. |