Minute Particulars

Blake Echoes in Victorian Dublin

At Morton Paley’s request, I went through the file of Kottabos in the library of Trinity College, Dublin: it consists of three volumes in the original series and two in the new series, running from 1869 to 1895, with a pause between the series in the 1880’s. Edited by the distinguished classical scholar Robert Yelverton Tyrrell, Kottabos normally appeared three times a year. Each issue, looking like a bound set of examination papers in spite of its pink paper cover, was dated according to the term in which it appeared—Michaelmas, Hilary, or Trinity. Apart from an occasional prose parody tucked in at the end of an issue, it consisted entirely of original verse and translations (usually verse) into and out of various classical and modern languages, but chiefly from English into Latin and Greek.

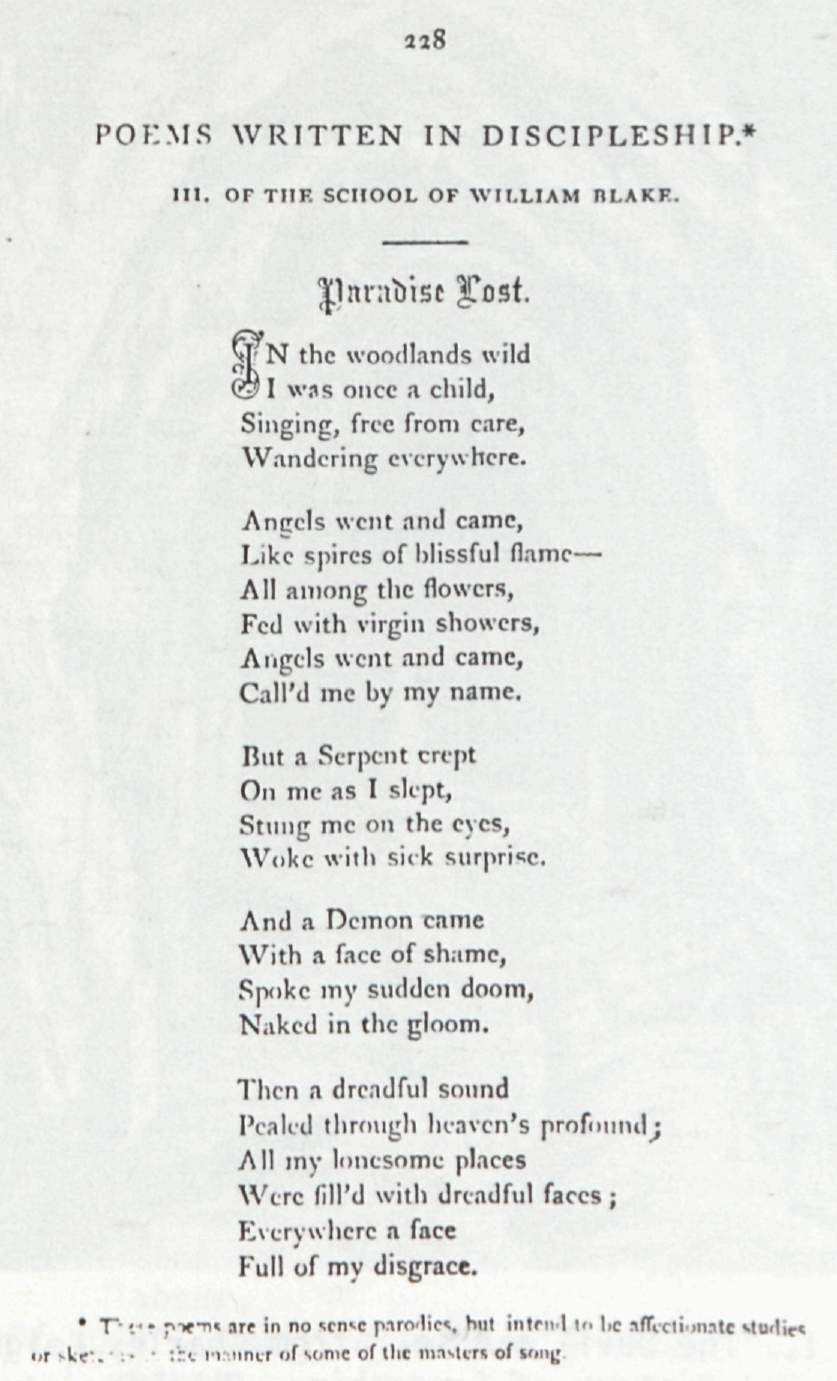

Most of the so-called original verse was extremely derivative; often the author made it perfectly clear that he was attempting only parody or pastiche. The series of “Poems Written in Discipleship” to which John Todhunter contributed his two imitations of Blake was usually accompanied by a footnote: “These poems are in no sense parodies, but intend to be affectionate studies or sketches in the manner of some of the masters of song.” In other words, they are exercises in pastiche. No doubt a parallel could be found in Songs of Innocence or Songs of Experience for virtually every line of Todhunter’s “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Found.” The most interesting aspect of these poems “Of the School of William Blake” may well be their date, since they appeared in the issue for Michaelmas Term (i.e. Fall Quarter), 1871. Another point worth noting, though it may be the result of pure chance, is Blake’s apparent high position in the batting order of the masters of song. Only Browning and Tennyson, in that order, had preceded him, both imitated by Edward Dowden, Professor of English Literature at Trinity, still remembered for his books on Shakespeare and Shelley. After Blake in the series came Longfellow (imitated by the otherwise unknown Percy S. Payne), Wordsworth (by Todhunter), “The Earlier Style of Euripides” (by R. Y. Tyrrell, in Greek), and Whitman (by Todhunter again). One might ask why Swinburne did not appear; the obvious answer is that practically all the “original” poetry showed his influence, especially that written by Oscar Wilde and his brother William. One might have expected Oscar to be aware of Blake, but his work for Kottabos offers no proof of this.

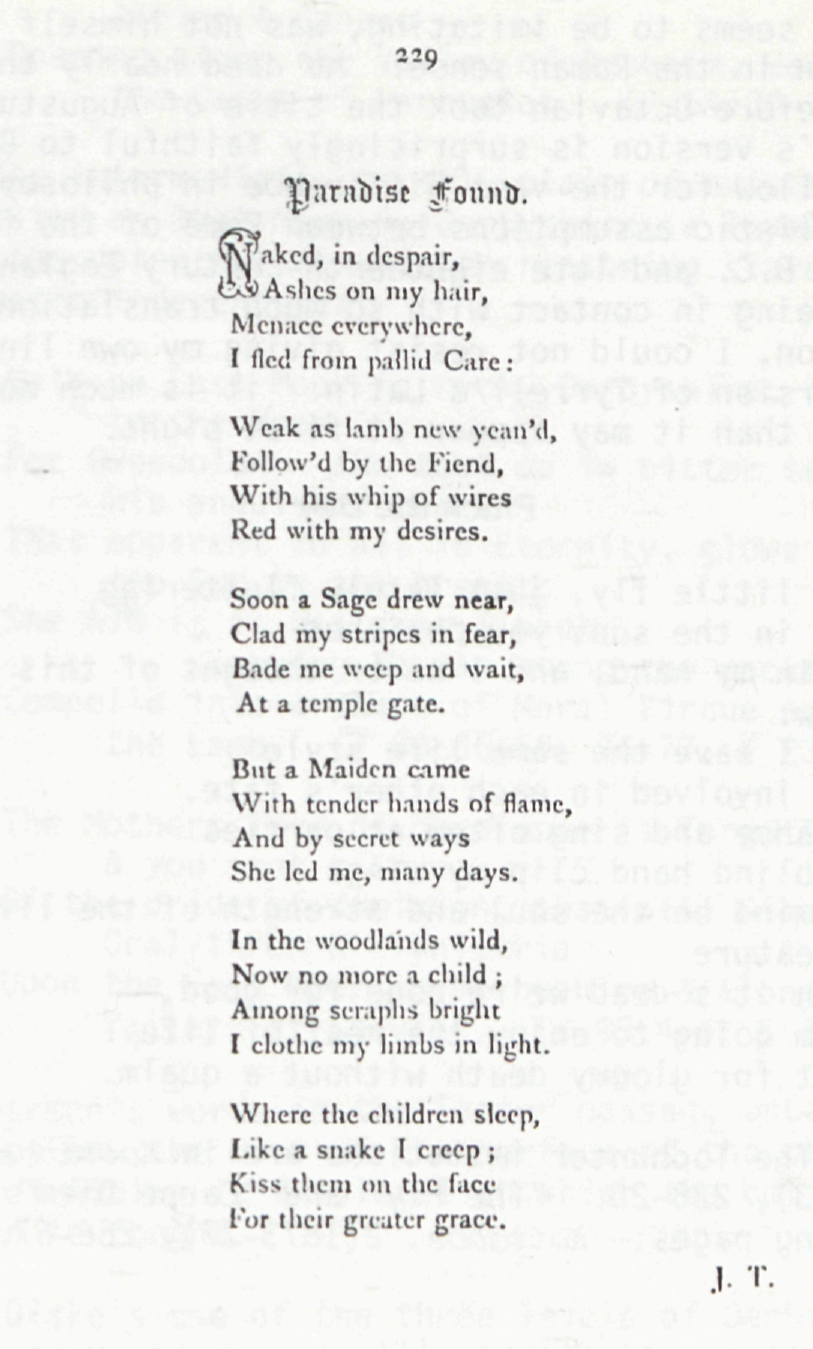

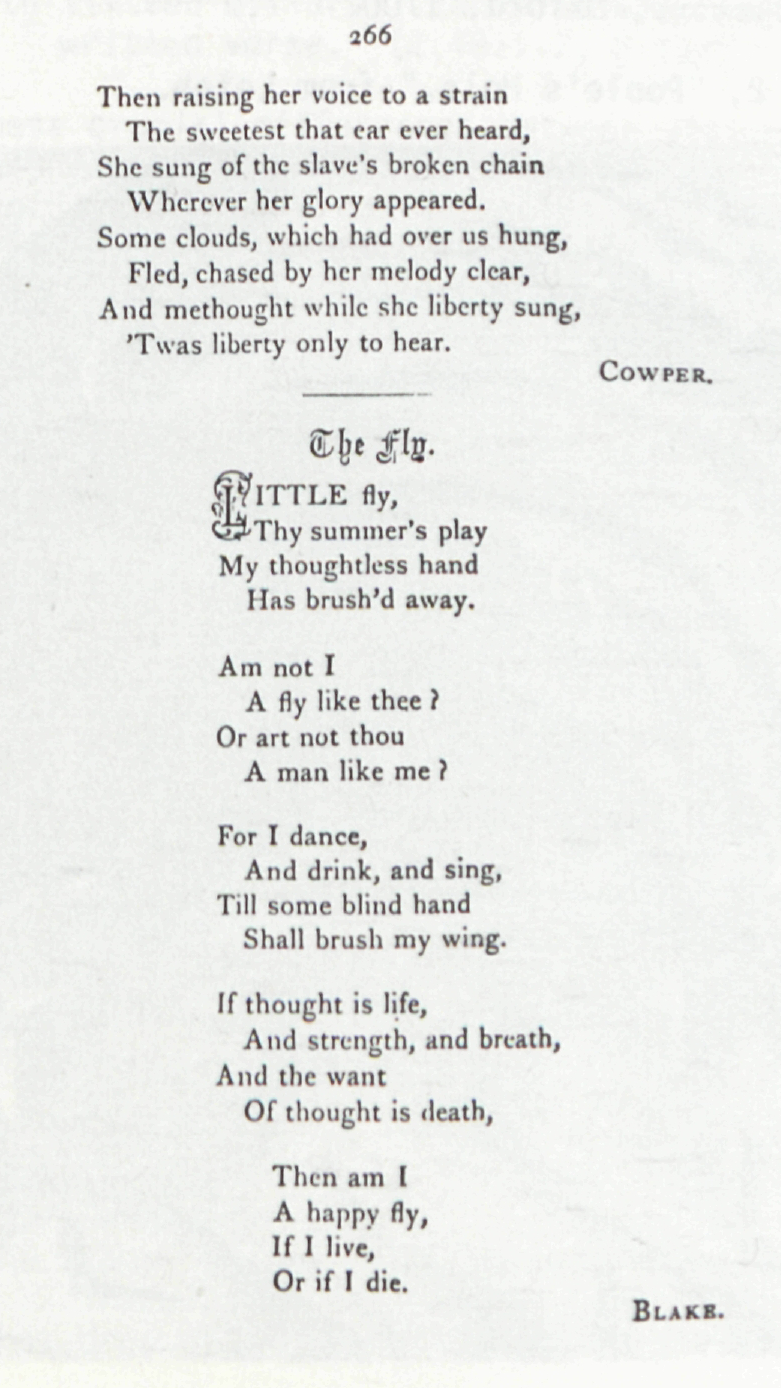

In the scholarly world of the time—and to a large extent in the literary world, too—Kottabos owed its reputation primarily to its contributors’ felicity in turning English poetry into Latin and Greek verse, a Renaissance accomplishment still highly prized among the Victorians. Shakespeare naturally offered the greatest challenge and was probably the most frequently translated author: classicists could not resist trying to turn Hamlet’s soliloquies into the rhetoric of the Greek tragedians. Milton and Pope, steeped as they were in the classics, went easily enough into Latin, though Dryden, perhaps because of his Catholicism, was neglected by the staunch Protestants of Trinity (Pope of course was Catholic, too; it was Dryden’s well publicized conversion to Catholicism in the reign of James II that caused Protestant resentment). Swinburne, as the author of Atlanta in Calydon, provoked attempts to translate him into Greek as well as Latin. On the other hand, those who cared more for grammar and meter than for belles lettres often turned to translating humorous stage-Irish ballads or mediocre album verse. R. Y. Tyrrell, over a number of years, hammered out a complete Latin version of Thomas Hood’s “The Bridge of Sighs” in the meter of the original—itself derived from medieval Latin verse. Given the above facts, you can imagine my surprise and delight at finding a Latin rendering of a Blake poem in the issue for Trinity Term, 1876. Blake’s “The Fly” is translated into eleven lines of Catullan hendecasyllabics under the hackneyed but appropriate title “Carpe Diem.” The Latin is signed “W. G. T.”—the initials of William Gerald Tyrrell, as we learn elsewhere in the issue. No doubt he was a relative of the editor.

It was shrewd of the translator to see how neatly Blake’s poem would fit into a classical subgenre. Too often we glibly categorize Blake as Romantic and ignore the “Augustan” element in his earlier work. By the way, Catullus, whom W. G.

Pluck the Day

Unlucky little fly, just lately fluttering

brashly in the sun, you perished

caught in my hand, and I never thought of this till now:

you and I have the same life style

and are involved in each other’s fate.

I too dance and sing often at parties

till a blind hand clip my wings.

But if mind be the soul and strength of the living creature

and when it’s dead we’re gone for good,

then I’m going to enjoy the rest of life

and wait for gloomy death without a qualm.

Note: The Todhunter imitations are in Kottabos, 1 (1869-73), 228-29. “The Fly” and “Carpe Diem” appear on facing pages: Kottabos, 2(1873-77), 266-67.

![267

Tum liquida teneros intendit voce canores

Queis equidem excepi dulcius aure nihil;

Vincula enim cecinit servis casura soluta

Undique qua, visu splendida, ferret iter.

Nubila, quae cymbae rara imminuere per auras,

Fugerunt magicis exsuperata modis;

Et rebar mecum, dum iura aequanda canebat,

Audiat haec quisquis carmina, liber, erit.

L. W. K.

Carpe Diem.

AH nuper volitans, misella musca,

Per solem, temeraria peristi

Nostra rapta manu, nec hoc putavi

Nostri vivere more te modoque,

Me vestri simul impedire fatum.

Sic convivia cum choris frequento,

Donec caeca manus recidat alas.

At si mens anima est vigorque vivi,

Hac autem pereunte deperimus,

Carpam quod spatium supersit aevi,

Mortemque impavidus morabor atram.

W[illiam] G[erald] T[yrrell]](img/illustrations/CarpeDiem.11.1.bqscan.png)