REVIEWS

William Blake: The Painter as Poet. An Exhibition Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Artist’s Death. March 19-May 29, 1977. Catalog by Donald A. Wolf, Tom Dargan, & Erica Doctorow. Garden City, NY: Library Gallery, Adelphi University, 1977. 24 pp., 9 pls. (1 in color). $1.50.

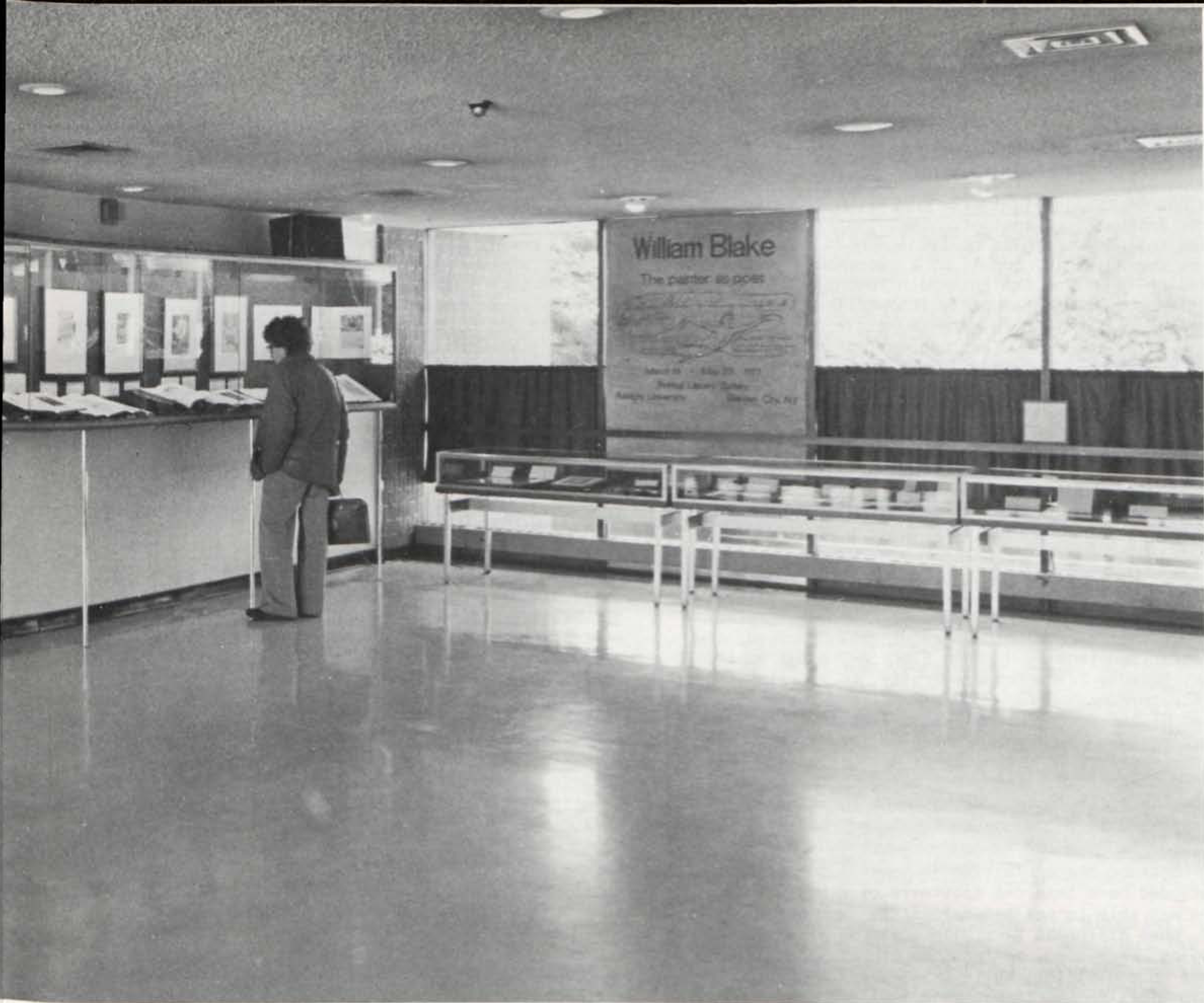

As part of a University Blake Festival commemorating the 150th anniversary of the artist’s death, the exhibition William Blake: The Painter as Poet was held at the Swirbul Library Gallery, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY, from 19 March to 29 May. Donald A. Wolf, Chairman of Adelphi’s Department of English, Erica Doctorow, Head of the Fine Arts Library, and Tom Dargan, consultant from State University of New York, Stony Brook, organized the exhibition and wrote the accompanying illustrated catalogue. The catalogue is essentially a word-for-word record of the exhibition labels and other posted explanatory material, and I shall refer below either to labels or to catalogue entries depending upon the context. Either of the two designations may be assumed to describe both. The exhibition consisted of 41 objects—15 original Blake works borrowed from various collections as listed below, supplemented by facsimile items mainly drawn from the Swirbul Library’s Leipniker Blake Collection with loans from the Hofstra University Library and Lessing J. Rosenwald.

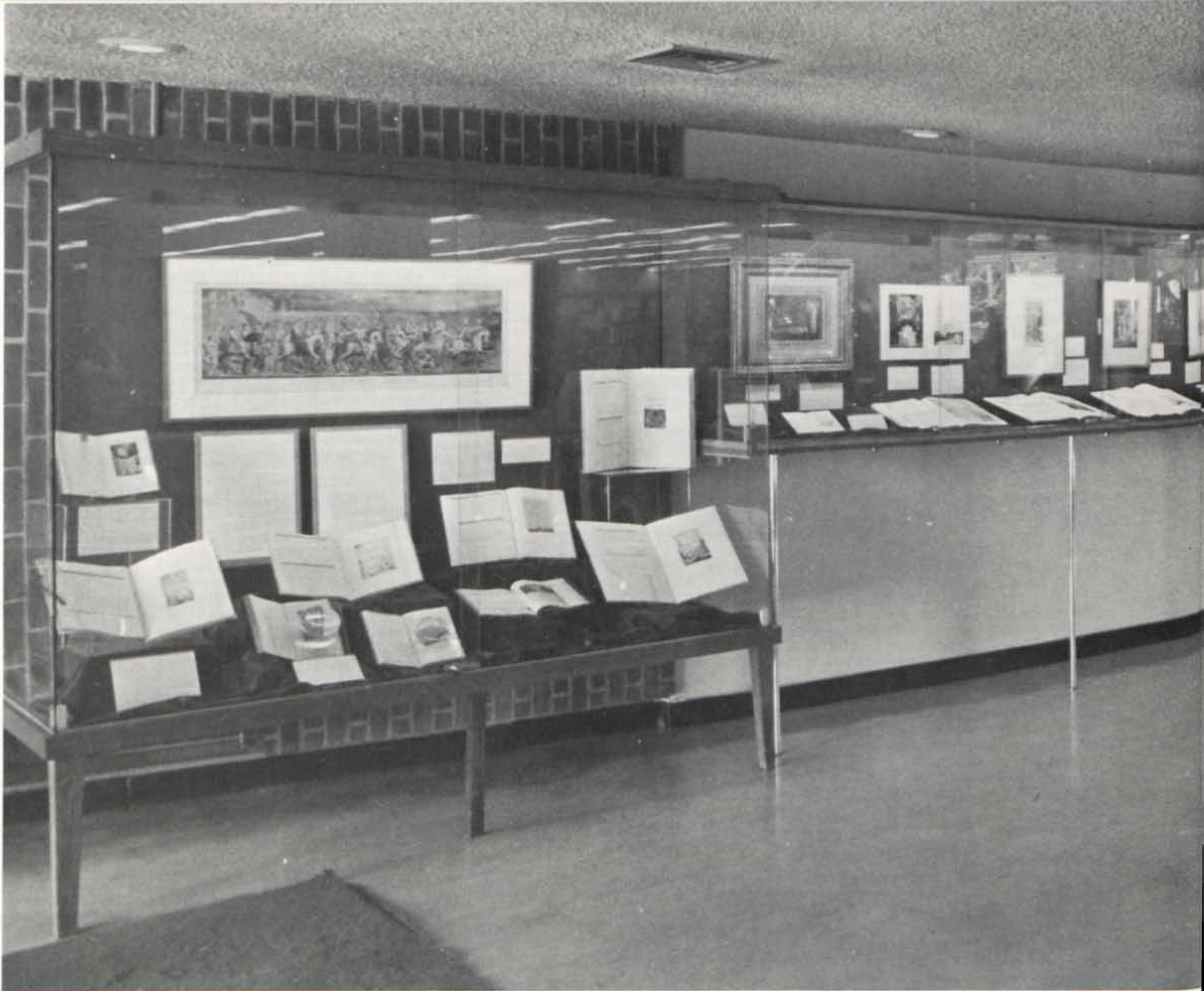

The exhibition was housed in an entrance gallery space with standing cases along ore wall and table cases along a second. It was directed to the broad university audience, possibly serving as an introductory Blake experience for many. The cases were begin page 111 | ↑ back to top

tightly filled but the installation was handsome; the works were placed upon felt and velvet of a brown-orange color similar to that used by Blake in surface printing, for example Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Copy V or Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Copy F.1↤ 1 This color was used for the catalogue cover-stock, text, and illustrations as well as for printed material related to the other Blake Festival events—clearly an effort to visually emphasize for the public the relationship among the several activities. For the catalogue illustrations, the color is sympathetic to reproduction of Blake’s relief printed works, but the engravings and the drawing do suffer. Magnifying lenses permitted a clearer view of particular objects and the volumes rested on plexiglas cradles. Unfortunately, labels occasionally were placed so that a novice viewer might easily have been confused about which labels referred to which objects.According to the catalogue introduction, the exhibition (which was inclusive enough to indicate the rich texture of Blake’s oeuvre and the complexity of his mythology) “focuses on the ways in which art and poetry contribute to the totality of his vision; and in doing so it explores a central theme, the contraries of innocence and experience in his work.” The introduction then provides Northrop Frye’s explanation of Blake’s contrary states of innocence and experience.2↤ 2 Northrop Frye, ed., Selected Poetry and Prose of [William] Blake (New York: Random House, 1953), pp. xxv-xxvii. Lacking in both the catalogue introduction and the accumulated catalogue entries was a broad statement explaining the relationships between the particular exhibited works in the context of Blake’s contraries of innocence and experience. Also, given that the exhibition was directed to a non-specialist audience, it would have been helpful if some explanation of Blake’s total system (of which this pair of contraries was a part) had been offered in the descriptive material. For the books, a paragraph summarizing the essential bibliographical information and more importantly the content or themes of volumes, followed by brief explanatory labels for each plate, would have helped make the exhibition easier to grasp than the repetitive (especially with the bibliographical material), somewhat fragmented labels that were provided.3↤ 3 Summaries and explanatory material were inconsistent in quantity and quality. For example, no overall picture was presented for The Book of Thel, or The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, while for The Song of Los, one was. In this regard, it is difficult to accept as explanation that “Visions is a feminist tragedy and something of a puzzle” (cat. 20). Interpretive entries at times lacked clarity. In some instances this results from the fragmentary presentation. For example, cat. 25 by implication refers back to cat. 24 in contrasting two “perspective(s)” on Urizen. Some entries are internally confusing, as in cat. 30, where in a description of plate 2 from Jerusalem, Milton is quoted without indicating the source. The entry is further unclear as to what a “labor hymn” is and whether the phrase refers to Jerusalem, the work being described, or Milton, the work being quoted. Facts, too, sometimes require clarification. In cat. 38, while the inscription on plate 1 of Illustrations of the Book of Job may indeed be read as “1828,” one presumes this is an error for 1825. As this review is to be of both the exhibition and the catalogue (unpublished labels are not the same as a published catalogue, even if the material is identical), I feel obligated to make one initial distinction—the selection of objects (the exhibition) was much richer than the explanatory material (the catalogue), which was more spirited than informative.

Along with one copy of Songs of Innocence (Trianon facsimile) and one of Songs of Experience (Muir facsimile) were two copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience (both Trianon); The Book of Thel presented in two copies (Trianon and Brown University Press facsimiles); The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in three copies (two Trianon and one Hotten facsimile). America, A Prophecy was presented both in facsimile and begin page 112 | ↑ back to top the original; the facsimiles were two copies of the Trianon edition, and the electrotype made from the copperplate fragment of cancelled plate “a” (in copy a* not A* as in cat. 19) in the National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. Importantly, the exhibition included the hand colored America frontispiece from the Philip H. and A. S. W. Rosenbach Foundation. Also on loan from the Rosenbach Foundation were the title page and frontispiece from Visions of the Daughters of Albion (Copy H) and the title page from The Book of Urizen.4↤ 4 Editorial inconsistencies which affect the quality of the information occur throughout the catalogue. To cite one example, the Rosenbach America frontispiece (cat. 17) is described as “Relief etching printed in blue painted with tan and blue watercolors” while the Rosenbach Visions title page and frontispiece (cat. 20 and 22) are described as “Relief etching painted with watercolors.” One might also note such editorial problems as the fact that both of Northrop Frye’s names are misspelled in the footnote to the Introduction. Visions was further presented in two facsimiles (Muir and Trianon), Urizen in one (Trianon). Europe, A Prophecy was represented by the hand colored frontispiece “The Ancient of Days” from the Rosenbach Foundation and plate 11 (uncolored) on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Song of Los, Milton, A Poem, and Jerusalem were all shown in Trianon Press facsimiles. An impression of Little Tom the Sailor, on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, further demonstrated Blake’s work in relief printing.

Blake as an engraver was seen in The Canterbury Pilgrims on loan from Maxine S. Cronbach, Christ Trampling Urizen and George Cumberland’s Card, the latter two lent by R. John Blackley, and from The Art Museum, Princeton University, four plates from Illustrations of the Book of Job, and restrikes from two of the seven (not six as stated in cat. 39) Illustrations of Dante, printed in 1968 from the engraved plates in the National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection. The one drawing in the exhibition was one of the wash drawings from the Tiriel series, “Tiriel Dead Before Hela” (lent anonymously).

Because the exhibition in several instances included more than one facsimile of a given book, one was able to see several plates from one book, or, when different facsimile editions (from various copies) were used, to focus on the variations Blake made on one plate. While this aspect of Blake’s investigative spirit was both implied and demonstrated by the exhibition, it was not pointed out or discussed; neither were the very real differences between facsimiles and originals. Adelphi was fortunate in obtaining several significant originals which made these differences clear but they might not have been noted by the novice viewer. A most cogent demonstration of the differences in the tactile life of printed surfaces and their effects on one’s responses to works of art might have been made by comparing the Trianon copy of The Gates of Paradise with any of the original engravings on exhibition. Attention might well have been brought to this difference, as well as to the variations in the quality and character of the different facsimile editions. I don’t mean to suggest that this ought to have been a major concentration but, rather, that within the context of an exhibition these points are important if the viewer is to see the significance of the nuances in Blake’s visual art.

The focus of the Adelphi exhibition was not one of art historical or bibliographical analysis or explication. The catalogue was undoubtedly published within a limited timespan and budget. It seems desirable, however, that certain basic information be included. To cite a few desiderata: one would like to have page or entry numbers throughout for references cited; would like to know that the impression of The Canterbury Pilgrims was in the fourth state (cat. 1); that the Tiriel drawing is one of 9 extant of a presumed series of 12, and something about the Tiriel poem other than that it “is about an old man who was really dead before his day, a despairing wanderer who cursed his children” (cat. 11); that the 1868 (J. C., not T. C.) Hotten facsimile of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell was the first published facsimile of a Blake illuminated book (cat. 9); be assured that inscriptions are accurately quoted, as, for example, the ones from Little Tom the Sailor (cat. 34) and George Cumberland’s Card (cat. 41) which are not;5↤ 5 “printed & sold by the Widow Spicer of Folkstone for the benefit of her orphans.” should read “Printed for & Sold by the Widow Spicer of Folkstone / for the Benefit of her Orphans / October 5, 1800” and “W Blake inv & sc: A AE 1827.” should read “W Blake inv & sc: / A Æ 70 1827.” “Experts” and “pupil” are best mentioned by name (because Keynes’ Engravings by William Blake: The Separate Plates is cited, one assumes that reference is being made to Sir Geoffrey Keynes and Thomas Butts, Jr. or Sr., cat.26); and finally, I have reservations about the words and phrases quoted throughout without citation.

Unfortunately, the catalogue perpetuates some fallacies. For example, to describe Blake in the introduction as having “found a way through his contemporary wasteland of indifference, ignorance and dullness” does a disservice to late 18th and early 19th century England.6↤ 6 As a recent and convincing denial of this premise, one might note Corlette Rossiter Walker’s William Blake in the Art of His Time, the catalogue for an exhibition held at the University Art Galleries, University of California at Santa Barbara, 24 February to 28 March 1976. To say that “Blake should be read with imagination. The reasoning intellect can tag along if it can keep up . . . ” (cat. 1) does a disservice to Blake’s contraries of reason and imagination. While Blake’s process for applying his texts to metal plates and his relief printing techniques may remain “Blake’s secret(s)” (cat. 19), not mentioning some of the recent experiments and theories related to these methods does a disservice to contemporary artists and scholars.7↤ 7 See Robert N. Essick, ed., The Visionary Hand: Essays for the Study of William Blake’s Art and Aesthetics (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, 1973), Part I: “Blake’s Techniques of Relief Etching: Sources and Experiments,” pp. 7-44 (includes Ruthven Todd’s essay “The Techniques of William Blake’s Illuminated Printing” originally published in The Print Collector’s Quarterly, 29 (Nov. 1948), here published with Todd’s revisions of the notes and new illustrations and (p. 44) the editor’s list of sources for other brief descriptions of the relief etching process); John W. Wright, “Blake’s Relief-Etching Method,” Blake Newsletter 36(Spring 1976), pp. 94-114; Robert N. Essick, “William Blake as an Engraver and Etcher,” pp. 16-17 in Walker, William Blake in the Art of His Time, op. cit. Furthermore, it seems shortsighted to state (in the introduction) that Blake was “neglected, regarded as an eccentric or a madman” by his contemporaries.8↤ 8 A less negative possibility is presented by Suzanne R. Hoover in her essay “William Blake in the Wilderness: A Closer Look at his Reputation, 1827-1863,” published in Morton D. Paley and Michael Phillips, eds., William Blake: Essays in Honour of Sir Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), pp. 310-48. While the essay attends to the period after Blake’s death, on p. 312 Hoover notes that “Of the seven obituaries that are known, one is derisive, but the others are appreciative.”

The Adelphi Swirbul Library exhibition brings into focus some problems facing Blake studies and also presents possibilities for future Blake exhibitions. While one laments the extensive use of facsimile objects (especially without adequate explanatory material), it has become clear that important unique Blake works (and one generally considers each copy of his books as unique) will be more and more difficult to obtain for other than major exhibitions (i.e., those that will both attract large audiences and make scholarly contributions via well-researched and imaginative catalogues). The organizers of the Adelphi exhibition indicated that institutions which in the past have been most generous in lending their other holdings for exhibitions were hesitant to release the Blake items. It is admirable that they organized their exhibition in spite of this obstacle. It seems that in the near future organizing an exhibition like William Blake: The Apocalyptic Vision held at Manhattanville College in Purchase, NY in 19749↤ 9 This exhibition, also held at a small, not centrally located educational institution, included several very important Blake watercolors and drawings as well as superb plates from the illuminated books. It was accompanied by an illustrated catalogue. will be difficult except in special circumstances.

Since 1974 the number of requests to borrow Blake material for exhibitions has increased dramatically. Various factors make repeated lending a problem. The primary one is concern for the care and preservation of the objects; increasing knowledge in the field of paper conservation has made many of us alter begin page 113 | ↑ back to top

Adelphi’s Blake festival included several inter-disciplinary[e] programs which took place concurrently with the exhibition—Tom Dargan’s illustrated talk, “Engraving Lessons from a Favorite Angel: William Blake’s Secret Printing Process;” “Eternity in an Hour” including “The Spoken Word,” readings arranged and directed by Nancy Miller and read by the University’s Story Players, and “The Visual Image,” a modern dance piece inspired by Blake’s poetry (with choreography by Norman Walker, music by Britten, lighting by Randy Klein, and costumes by Linda Cliggett) which was performed by the senior dance majors; and the world premiere of a structuralist opera, commissioned especially for the Blake Festival, “Willy” or “Auguries of Innocence.” The opera was written and directed by Jacques Burdick and Thomas Vuozzo and performed by students in the Theatre Program. According to Mr. Burdick, Director of the Department of Performing Arts Theatre Program, the opera based on Blake’s life, times, visions, and works began as a class project in a Radical Theatre course concerned with the structuralist tenets of the French linguist Jacques Lacan. The particular problem was how to translate Blake’s vision to sound. When it became apparent that the project as envisioned would become a five or six hour trilogy, the group determined to concern itself, for the time, with only the first part, “Willy” (Blake’s use of his powers of sight in infancy and youth). The remaining two sections are conceived as “Will Blake” (youth and maturity) and “Mr. William Blake” (Blake’s prophetic powers in old age). Mr. Burdick noted in the program that the group was hoping for financial assistance to “stir up ‘Willy’ and allow him to spring, like the phoenix, into the triple flight of a complete realization of our project.”

A lighter facet of the Blake Festival was the production of Blake tee-shirts. Available from the same address as the catalogue, the tee-shirts bear Blake’s autograph (Berg Collection, New York Public Library), and come in sizes S, M, L, XL, in yellow, red, blue, white, royal and brown. The cost is $5 + .50 shipping. The University requests prepayment for the exhibition catalogue and the tee-shirts.

begin page 114 | ↑ back to topThe exhibition catalogue is available from the Fine Arts Library, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY 11530, for $1 + .50 shipping.