review

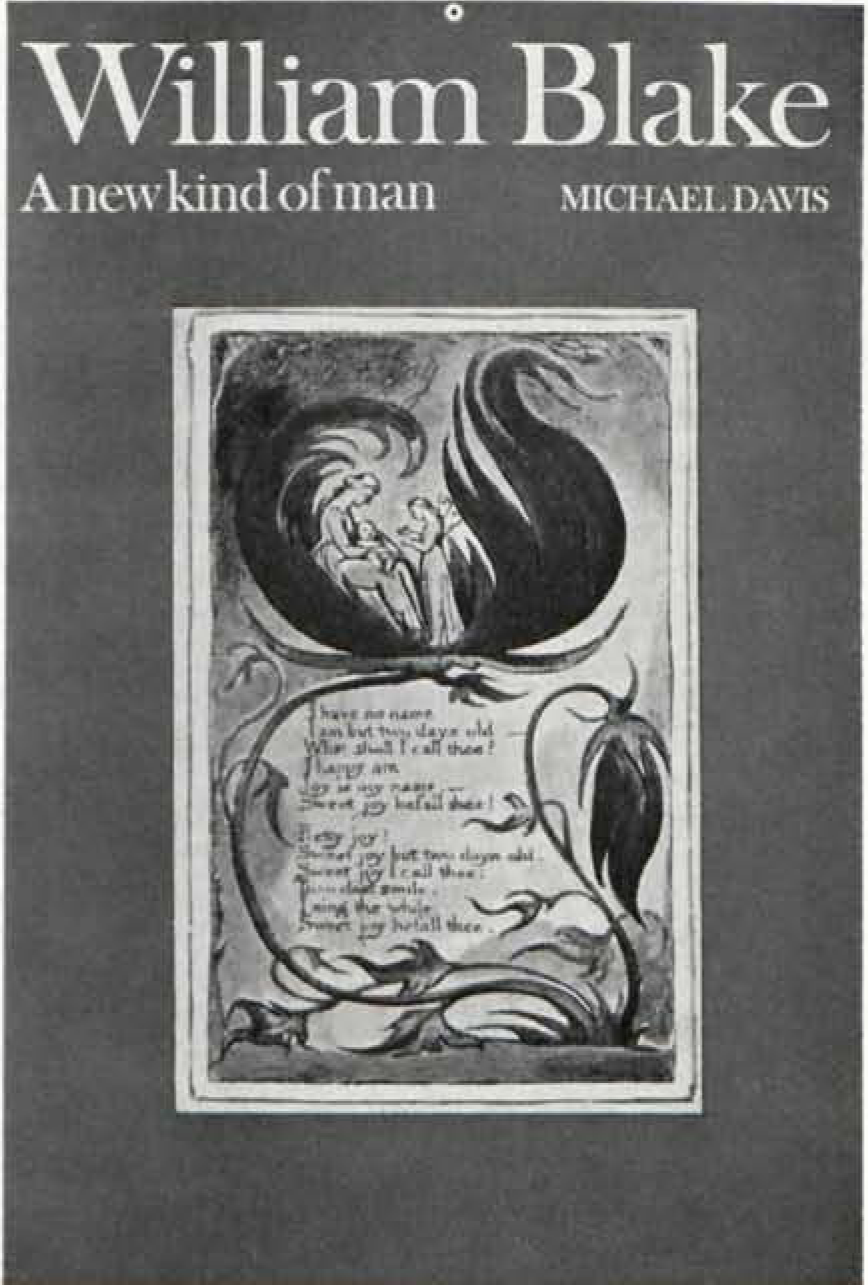

Michael Davis. William Blake: A New Kind of Man. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977. 58 black-and-white illustrations, 8 in color. $12.95.

A fully developed biography of Blake which reverses the distortions of contemporary gossip and subsequent critical confusion is a major priority of Blake studies. Michael Davis has produced a diligent and enthusiastic book, but one which does not answer this need. It offers neither the new historical information nor the new theoretical approach which would justify a new biography, and it does not assemble old knowledge in a productive way.

What is suggestive in this volume is the sense it provides, in plates and brief descriptions, of the physical environments in which Blake worked. This suggestiveness is not realized, however, in any developed analysis of the effect on Blake’s life and art of these environments.

Davis studied widely in contemporary sources, both graphic and verbal, but most of what he studied has been studied before. Any originality is lost in his narrative method, which absorbs generations of critical commentary without annotation. His account, for example, of the connection between Blake and John Stedman and the effect of that connection on Visions of the Daughters of Albion is useful, but does not progress beyond accounts by Erdman and Keynes; that it does not makes the reader skeptical that any of Davis’ other observations goes beyond his sources.

There are rhetorical problems which also undermine a reader’s confidence in this study. One of these problems is a distracting carelessness in tone. Davis calls The Marriage of Heaven and Hell a book “whose sharp ambiguities, versatility and irreverent humour bubble with imaginative energy” (p. 61); he asserts flatly that “The biblical story of Job does not solve the problem of suffering. Blake’s twenty-one pictures do” (p. 143); he notes in passing that Mary Wollstonecraft “pursued Fuseli for a while” (p. 38), as if she were either Vala or a boy-crazy ninth-grader. These are certainly minor lapses, but they are characteristic, and they occasionally yield to graver insensitivity: “In Blake’s illustrations [of Visions of the Daughters of Albion], Oothoon is white, as befits the soul of slavery . . . . She could say, with the little black boy in Songs of Innocence, ‘I am black, but O! my soul is white’” (pp. 54-55, emphasis mine). There is debate over the degree, even the existence of irony in Blake’s use of such imagery, but however much or little irony we allow Blake, we cannot allow a critic in 1977 to pass off without clearly defined ironic purpose an attitude which equates goodness with whiteness and paternalistically assumes that blacks are, contrary to appearances, just as good as anyone else.

Another rhetorical problem is a confusing vagueness in Davis’ definitions of Blake’s myth: “Single vision is seen by the eye only; twofold vision sees through the eye and perceives the human value in all things; threefold vision reveals thought in emotional form and inspires begin page 290 | ↑ back to top creation; fourfold vision is mystical ecstasy” (p. 25, emphasis in original).

This kind of rhetoric is much thicker in the opening chapters of A New Kind of Man, perhaps because in these chapters Davis deals with a period of Blake’s life for which there is little documentation. As soon as he gets to Blake’s maturity, about which there is, if not full documentation, at least a lot of recorded gossip, his narrative settles into a genial commentary linking quotations from Blake’s prose (particularly his letters) and his contemporaries’ accounts of him.

For all its geniality, however, that narrative has two major deficiencies. First, its interpretations of Blake’s thought and art are often either hopelessly over-simplified (you cannot legitimately say in one sentence that “Blake respected Newton, as he did Bacon and Locke . . . ” and then add in the next, without explanation, “A scientific trinity who gave form to error, they are counterparts of ‘Milton & Shakspear & Chaucer’, who expressed truth” [p. 69]), or just plain wrong: “Blake stooped to fasten his shoe before walking out to seek inspiration for his poem Milton in the Vale of Lambeth” (p. 47); “In complete contrast to that unlovely attack [in Tiriel] on a world in which imagination has been murdered by repression, shines his exultant, endearing masterpiece of the same year, 1789, Songs of Innocence, surely a labour of love” (p. 43); “The Fall is experienced by every person. It occurs in each individual’s life at adolescence and changes Innocence into Experience” (p. 55).

Second, major terms of the biography are neither defined nor demonstrated. Davis calls Blake, at least from 1787-93, a revolutionary (chapter 3 and passim), a man “subversive but neglected” (p. 63); he insists that “there is no doubt that Blake held seditious views” (p. 106). Blake’s revolutionism is a principal tenet of the book, but Davis’ one real attempt to describe it is almost comically imprecise: he calls Blake a radical, citing as evidence his outrage at the war against the American colonists and noting in the next sentences that “Blake also detested government. At Basire’s he had engraved some of the many illustrations in a book of memoirs by Thomas Hollis, an ardent devotee of Milton’s grand, ideal [?] republicanism, and Blake found Milton’s revolutionary fervour very congenial” (p. 24). Radicalism, war opposition, anarchism, republicanism, revolutionism—all equated, none defined. Exactly what seditious views did Blake hold? What is a revolutionary anyway? One could argue that a poet who calls in his or her work for revolutionary change is a revolutionary—Davis does not develop such an argument about Blake. In fact, he seems to belie it: he hypothesizes that The French Revolution may have been abandoned because, “in an era when a revolutionary would, if discreet, avoid political subjects to keep himself out of Newgate” (p. 50), this revolutionary Blake, “a prey to ‘Nervous Fear’ of imprisonment, himself withdrew the poem” (p. 48). What kind of revolutionary? One who promulgates revolutionary ideas only when they are safe and harmless? Similarly but less significantly, the “Pilgrimage in Poverty” which titles Chapter 7 is a pilgrimage unexplained. What kind of pilgrimage?

In short, the “new kind of man” this biography sets out to describe never emerges. The phrase itself, taken from Francis Oliver Finch, seems to refer mostly to Blake’s emphasizing his “extreme opinions” (p. 154). What new kind of man? The portrait we get in this book is not only not of a new kind of man, it is an old kind of portrait. Davis’ Blake is an alternately gruff and ecstatic eccentric who is, Davis insists (must we still insist this?), not mad—but whom anyone not his intimate would be justified in taking for mad, so uncompromisingly strange did he choose to make himself seem in public. Even Davis’ readers might feel so justified: we are meant to see here a revolutionary heroically true to his vision, but we are given so little understanding of that vision that we might as easily see instead a dirty, crabby fanatic. This portrait of Blake is as retrogressive as the criticism which once again turns the Songs of Innocence and of Experience into a puberty crisis.

I do not know why this biography was undertaken, unless it was to allow the author to spend time and energy on a figure he admires. That is a fine ambition, and I in no way wish to demean it. Michael Davis reads like an amiable man with a strong if not penetrating appreciation of a great poet. I wish there were millions of such people. I wish there were as many books as people can write. Since there are not, I must question why the University of California Press chose to publish this one.