article

begin page 10 | ↑ back to topTHE FIGURE IN THE CARPET: BLAKE’S ENGRAVINGS IN SALZMANN’S ELEMENTS OF MORALITY

The attribution of the unsigned plates in the English translation of C. G. Salzmann’s Elements of Morality 1↤ 1 First published by Joseph Johnson in 3 vols., 1791. The plates also appear in editions of 1792 (second state), 1799 (third state of most plates), 1805, and the undated “Juvenile Library” edition (1815?). has had a checkered career. In the first edition of his Life of William Blake, Alexander Gilchrist wrote that Blake “illustrated” Salzmann’s “pinafore precepts,” leaving it unclear as to whether Blake simply engraved the plates, designed them, or both.2↤ 2 London and Cambridge: Macmillan, 1863, I, 91-92. The ambiguity was corrected for the second edition (1880, I, 91), where the German artist Daniel Nicolaus Chodowiecki (1726-1801) was named as the designer and Blake as the engraver. The change may have been prompted by a brief note by Frederick Locker on “The Illustrations in Mrs. Godwin’s ‘Elements of Morality,’”3↤ 3 Notes and Queries, I, 6th S. (19 June 1880), 493-94. Locker concludes with the comment that “I trouble you with this as I understand that Mrs. Gilchrist is now engaged on the pious work of re-editing her late husband’s book.” which points out that the plates were designed by Chodowiecki with the exception of those numbered 27 and 28. These two plates were exhibited at the Grolier Club in 1905 and described in the catalogue as being of Blake’s “own designing.”4↤ 4 Catalogue of Books, Engravings Water-Colors & Sketches by William Blake ([New York]: Grolier Club, 1905), no. 67 p. 102. This attribution of pl. 27, at least to Blake as the engraver, can be rejected with a fair degree of confidence because, like the frontispiece to vol. I and pls. 1, 7, 10 (signed W. P: C fect 1790), and 11, it was clearly executed by someone other than the engraver of the remaining forty-five plates and looks not in the least like Blake’s hand. In his catalogue of 1912, A. G. B. Russell, exercising his usual skepticism about Gilchrist’s casual attributions, lists only fourteen plates as Blake’s copy work, including eight “possibly, but not certainly, by Blake.”5↤ 5 The Engravings of William Blake (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1912), pp. 156-58. In his great Bibliography of William Blake of 1921, Geoffrey Keynes ascribes sixteen plates to Blake,6↤ 6 New York: Grolier Club, pp. 235-37. only ten of which are the same as those listed by Russell. Keynes takes note of the Grolier catalogue attribution of pls. 27 and 28 and comments that “the treatment of the trees and vines in the second of these (pl. 28) certainly suggests Blake’s work,” but then rejects this idea because both “plates were obviously not engraved by him.” Bentley and Nurmi are a bit more generous, crediting Blake with seventeen plates but expressing judicious uneasiness over the whole business of attribution on stylistic grounds.7↤ 7 G. E. Bentley, Jr., and Martin K. Nurmi, A Blake Bibliography (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1964), pp. 149-50. Bentley repeats the same list in Blake Books. 8↤ 8 Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977, pp. 607-09. As in Bentley and Nurmi, the name of the designer is incorrectly given as “David Chodowiecki.” None of these authorities indicates how he made his selections; to my eye, all but the six (listed above) by another hand, and possibly pl. 48, are by the same engraver, or at least by a group following a “house style” as in the Novelist’s Magazine. A comparison of the English plates illustrating Salzmann with their German prototypes provides new evidence for Blake’s involvement. More surprisingly, it suggests that the Grolier catalogue may be right about pl. 28.

Chodowiecki’s seventy designs were first published in Kupfer zu Herrn Professor[e] Salzmanns Elementarwerk nach den zeichnungen Herrn Dan. Chodowiecki, von Herrn Nussbiegel Herrn Penzel und Herrn Crusius Sen. gestocken. 9↤ 9 Leipzig, 1784. Locker—and following him the 1905 Grolier catalogue, p. 102, Russell, p. 156, and Keynes, p. 236—point out that the illustrations are in the Leipzig, 1785, edition of the Moralisches Elementarbuch and do not note the earlier appearance of the plates alone. Among the forty-five plates not by the “other hand” in the English edition, all but pl. 28 are based closely on Chodowiecki’s designs, and were probably copied directly from the German plates. There are, however, some minor but substantive differences between fourteen of the prints. These variations are not significant enough to suggest that another artist was hired to adapt Chodowiecki’s designs—they are still very much his—and were no doubt made by the English engraver(s). These changes are listed below, along with speculations on why some were made.

Pl. 3. The rather elegant floor divided into large squares in the German plate is replaced by a carpet in the English. Both seem equally appropriate since the design shows the drawing room in Sir William’s “grand house” (I, 16 in the 1791 edition). I have not been able to find out if English drawing rooms were more frequently carpeted than the Continental variety.

begin page 11 | ↑ back to topPl. 20. The place setting on the table in the German print has been eliminated in the English, and two children added on the left. The first change follows the text, for the scene takes place “after the cloth was taken away” (II, 48). The text does not specifically place the children in the scene, but they are mentioned (II, 49) in the conversation between the husband and wife pictured in both plates.

Pl. 26. The curtain covering part of the back wall in the German plate has been replaced with what looks like patterned wallpaper in the English. There seems to be no textual reason for this, unless wallpaper is more appropriate for the breakfast room setting.

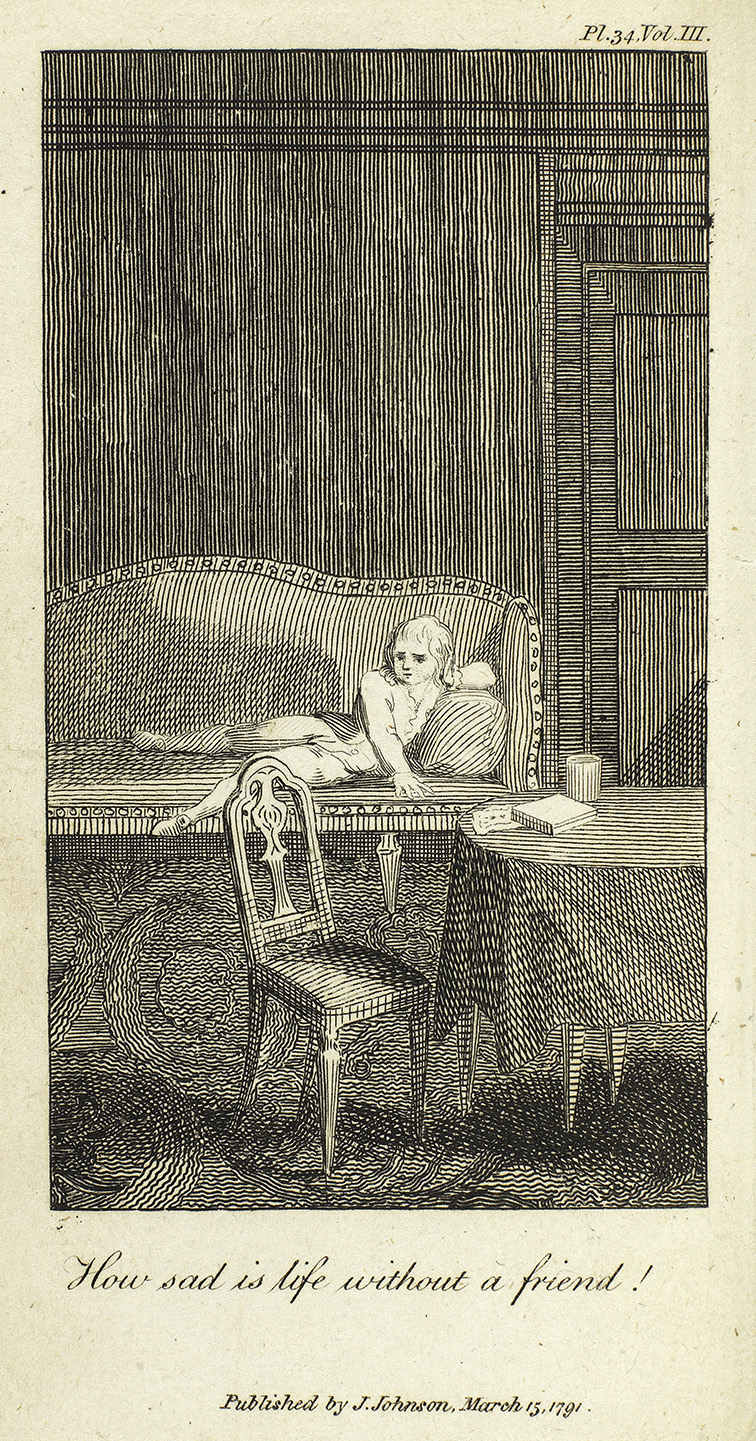

Pl. 34 (illus. 1). The German squared floor is replaced in the English copy by a carpet, and the back of the chair has been shortened so as not to cover as much of the boy’s legs.

Pl. 37. The round knobs on the chest of drawers in the German plate have been replaced in the English copy by handles of the sort more commonly found on eighteenth-century English furniture.

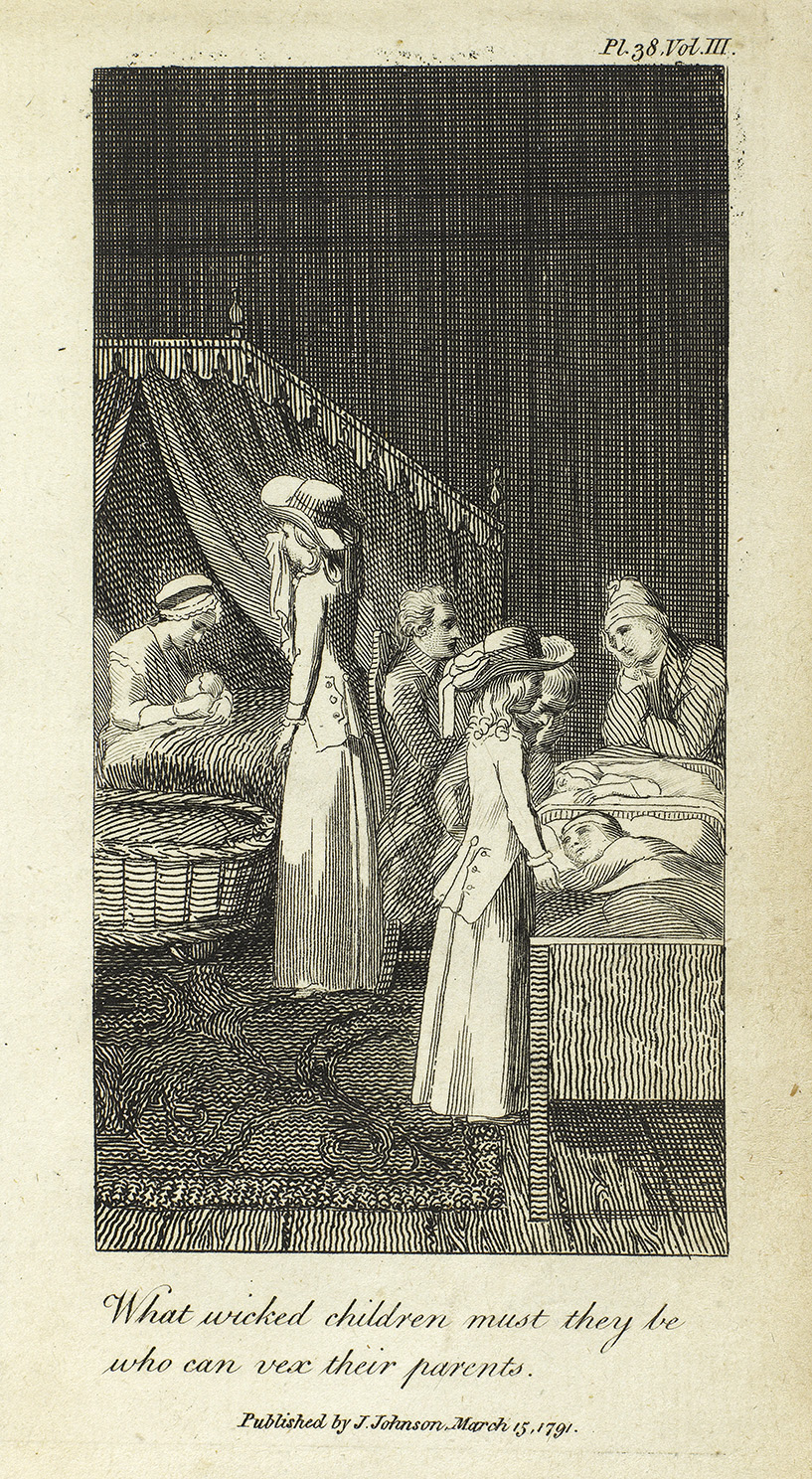

Pl. 38 (illus. 2). The German squared floor has been replaced by rough boards and a carpet in the English copy. At least the boards seem more appropriate than the squared floor, for this is the room of a poor and desperately sick family. The wicker basket on the left does not appear in the German plate. It is probably the cradle of the infant at his mother’s breast and is reminiscent of the basket-cradles in Blake’s “A Cradle Song” (second plate) and “Infant Sorrow.”

Pl. 41. The German squared floor has been replaced in the English plate by a crosshatching pattern apparently representing boards.

Pl. 42. The desk and man’s legs visible through the railing in the German plate have been obscured with crosshatching in the English.

Pl. 44. The sleigh in the German plate has been replaced by a cart, and the second sleigh on the far right replaced by a horse and rider. Both changes follow the English text, for the family is specifically placed in a “cart” three times (III, 116, 117, 123) and there is no reference to a second cart or sleigh. “The boy who rode on the first horse” (III, 123) probably refers to a servant riding on the lead horse hitched to the cart, but may have prompted the addition far right.

Pl. 45. The German squared floor has been replaced by a carpet in the English copy. As in pl. 26, the setting is a breakfast room. (Salzmann was a forerunner of Oliver Wendell Holmes in the pedagogic uses of the breakfast table).

Pl. 46. The back wall, divided into large panels in the German plate, has been made plain in the English copy, and carpet replaces the German squared floor.

Pl. 47. The floor and back wall are smooth and even in the German plate; but in the English copy the floor looks rough and uneven, and the wall is cracked

Pl. 50. The German squared floor has been replaced in the English copy by smooth boards, and a few decorative swirls have been added to the curtain behind the bed.

The alterations in pls. 20, 38, 44, and 47 show a careful responsiveness to the text which is most unusual for simple copy engravings in a children’s book. This fact alone suggests the habits of mind of the engraver of the Night Thoughts and Job illustrations, but it is a seemingly insignificant addition to the English plates that points more directly to Blake.

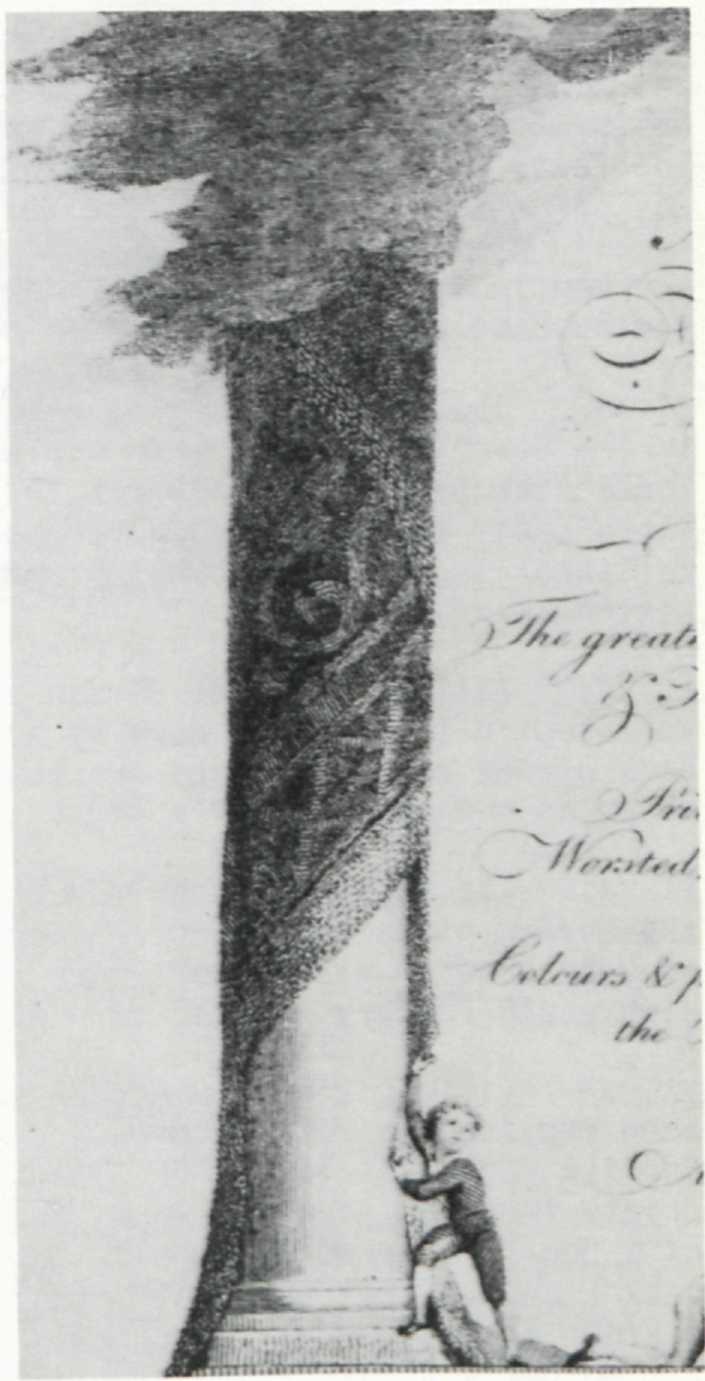

The carpets added to pls. 3, 34, 38, 41, 45, and 46 bear the same bold swirls, arabesques, and vegetative motifs (see illus. 1, 2). On pls. 26, 29, and 43, the engraver has modified Chodowiecki’s original carpets to picture this pattern. The same sort of carpet appears in three plates unquestionably by Blake. In 1788 Blake etched and engraved his fine plate of Hogarth’s “Beggar’s Opera.” The carpet (illus. 3) beneath Macheath’s left foot is a larger version of those in the Salzmann illustrations. Except for the swirls in the lower left corner, the pattern is only vaguely suggested in Hogarth’s oil painting (Mellon collection). Its specific deliniation in the print is as much the engraver’s as the designer’s. That this particular carpet became part of Blake’s decorative repertoire is confirmed by its reappearance in two later original graphics: the “Moore and Co’s Advertisement” of c. 1797 (illus. 4)11↤ 11 Keynes, Engravings by William Blake: The Separate Plates (Dublin: Emery Walker, 1956), p. 15, dates the plate c. 1790 because of its similarity to the Wollstonecraft illustrations, but David. V. Erdman, “The Suppressed and Altered Passages in Blake’s Jerusalem,” Studies in Bibliography, 17 (1964), 36 n. 34, points out that Moore & Co. is listed only in the London directories of 1797 and 1798 and that the firm apparently had no other names in earlier years. and the final plate in Designs to a Series of Ballads of 1802.

The appearance of the carpet pattern—as it were, a Blakean signature—in some of the Salzmann plates lends new credence to the contention that Blake was their engraver. And if we attribute the carpet plates to him, I find it impossible to go through the other forty-five candidates and weed out definite non-Blakes, with the possible exception of pl. 48. There is of course a natural resistance to attributing to Blake’s hand all this undistinguished hack-work. That, however, should not stand in our way. By 1790 Blake was a very skilled etcher-engraver (witness the Hogarth plate), but he inevitably modified his style according to the genre in which he was working—and no doubt according to begin page 13 | ↑ back to top the fee as well. For example, in 1784 Blake engraved two sophisticated “fancy” stipple prints after Stothard, “Zephyrus and Flora” and “Calisto,” and in the same year produced six crude plates for The Wit’s Magazine. In each case, the style is appropriate for the subject, and the latter group perfectly suited to the rough humor of their literary context.12↤ 12 Keynes makes much the same point about the Wit’s Magasine plates in “Blake’s Engravings for Gay’s Fables,” The Book Collector, 21 (1972), 60. This Blakean version of eighteenth-century rules of decorum is a persistent feature of Blake’s entire career as a graphic artist. For a children’s book like the Elements of Morality, the simple mixed-method plates are appropriate for the simple moralistic tales they accompany. The same may be said for Blake’s relief etchings in Little Tom the Sailor, for which the artist himself pointed out the principle of decorum: “they are rough like rough sailors.”13↤ 13 Letter to William Hayley, 26 Nov. 1800. The Letters of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes, 2nd ed. (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1968), p. 49. When compared with other prints of the period intended for a youthful audience, such as the Carver & Bowles “catchpenny prints” or those in Banbury chap books,14↤ 14 For some examples, see Catchpenny Prints: 163 Popular Engravings from the Eighteenth Century (New York: Dover, 1970) and Edwin Pearson, Banbury Chap Books and Nursery Toy Book Literature (London, 1890; rpt. New York: Burt Franklin, n. d.). the Salzmann plates seem almost elegant. That they are less accomplished than the Wollstonecraft illustrations, begun in the same year as the last of those for Salzmann, can be attributed at least in part to the fact that in one case Blake was executing signed plates after his own designs, and in the other rapidly producing a good many unsigned copy prints.

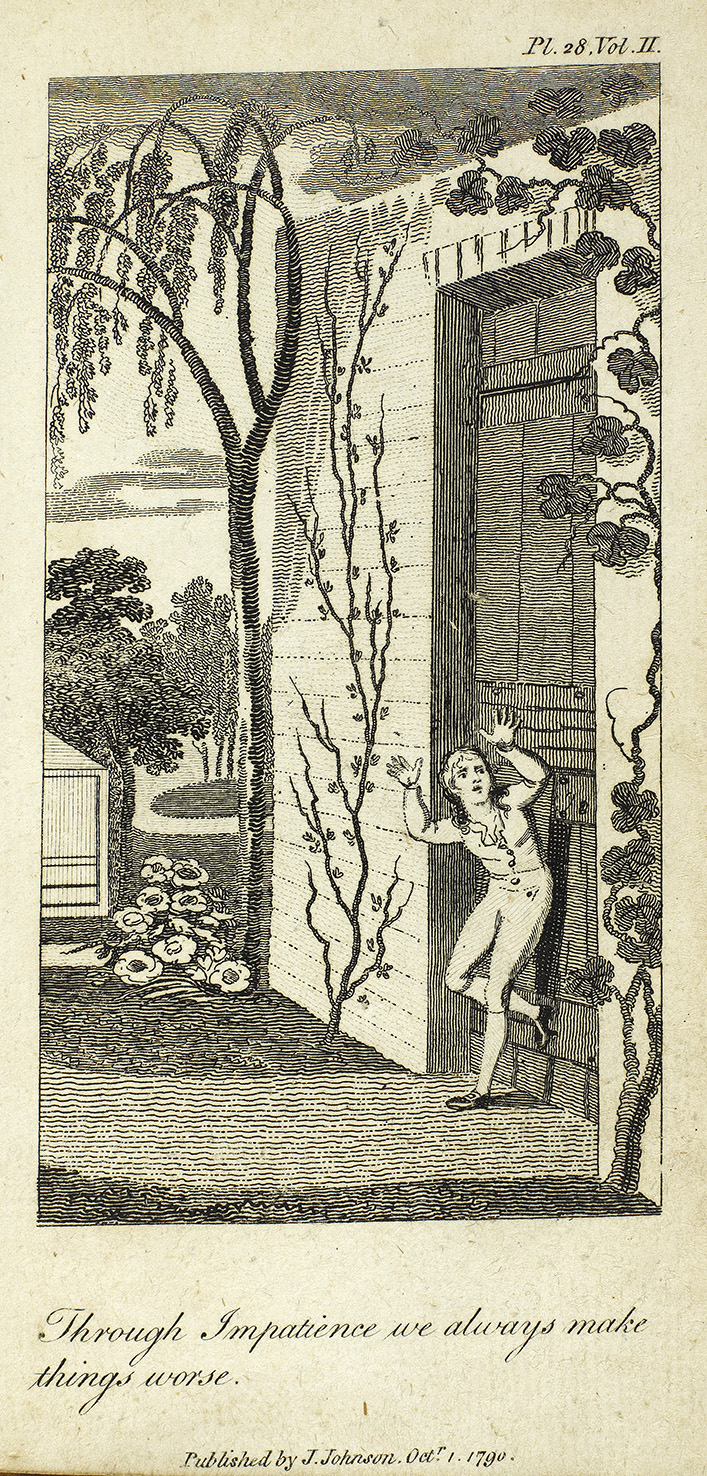

Plate 28 (illus. 5) offers the greatest challenge to the chalcographer. At first glance it would seem to be one of the prints executed by the “other hand.” But this is only because the smallness of the figure relative to the size of the whole design is similar to the frontispiece to vol. I and pl. 27; in graphic style pl. 28 is strikingly different. Most of the prints throughout Elements of Morality suffer from the horror vacui endemic among eighteenth-century engravers, although those plates most frequently attributed to Blake in the past are less cluttered than the others. Plate 28 is the most open of them all, with the worm lines so much a part of Blake’s early style but remarkably little crosshatching. Blake used a similarly open, etched style, deriving from Salvator Rosa, in two plates after Fuseli, “Timon and Alcibiades” and “Falsa ad Coelum” of 1790, and attempted to combine it with more conventional patterns in the Night Thoughts engravings (1796-97) and the illustrations, also after Fuseli, for Charles Allen’s New and Improved History of England and New and Improved Roman History, both of 1798. Almost every motif in pl. 28 also has its parallel in Blake’s work. The slender tree with arching branches recalls those in “The Lamb,” “Night” (first plate), “The Little Girl Lost” (first plate), the title-page of The Book of Thel, and America pl. 7. A much stronger parallel is between the vine on the right margin of pl. 28 and that on the right in the frontispiece to Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories (illus. 6), also climbing up a wall next to a portal. The delineation of the leaves is almost identical. The general subject—a child or children before a large doorway—can also be compared to the Wollstonecraft frontispiece, “Nurse’s Song” in Songs of Experience, and The Book of Urizen pl. 26. This last example also contains a heavy wooden door as in the Salzmann plate, but the closest parallel for the setting is the water color illustration to Young’s Night Thoughts, Night II, p. 7, where Blake also pictures a gigantic door in a curiously free-standing wall. Salzmann’s text indicates that William, pictured in pl. 28, is locked

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]