review

RECENT WOLLSTONECRAFT

Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary, A Fiction, and The Wrongs of Woman. Edited, with an introduction, by Gary Kelly. London: Oxford University Press, 1976. Pp. xxxii + 231. $12.00.

Mary Wollstonecraft. Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Edited, with an introduction, by Carol H. Poston. Lincoln, NB, and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1976. Pp. xxiv + 201. $11.50 cloth, $4.95 paper.

Ralph M. Wardle, editor. Godwin & Mary: Letters of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Lincoln, NB, and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1977. Pp. x + 125. $2.65 paper.

Mary Wollstonecraft. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Edited, with an introduction, by Miriam Brody Kramnick. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1975. Pp. 319. $3.95 paper.

Claire Tomalin. The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. New York and London: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1974. Pp. xii + 316. $8.95.

The Romantic Period was less an age of feeling than the reaction against an age of feeling. By 1790 the case for sensibility had been made all too well. The Romantics may have talked about poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling” and “the lava of the imagination whose eruption prevents an earth-quake,” and they may have dreamt of “a Life of Sensations rather than Thoughts,” but what they did was turn back from the heart to the mind. The masterpieces of the first quarter of the nineteenth century—The Prelude and Don Juan, Pride and Prejudice and Waverley—speak to people who think as deeply as they feel. Perhaps the Imagination itself appealed to the Romantics because with it they could close up the rift that had opened in the eighteenth century between intellect and emotion: the Imagination was preeminently a faculty of the active, creative mind.

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, already dissatisfied or just bored with the cult of feeling, writers of differing intentions and sympathies struggled with the problem that the Romantics later solved triumphantly. The sentimental had reached a kind of apogee in Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778): reunited with the father who had deserted her and her mother when she was an infant, Evelina falls weeping to her knees five times in a single conversation, and her repentant father, also in tears, kneels three times and stays down longer. A few minutes of crying can atone for sixteen years of neglect. In Northanger Abbey and Sense and Sensibility Jane Austen attacks this kind of absurd sentimentalism, and in The Prelude Wordsworth acknowledges the temporary attraction of a system of values that resembles Austen’s at its simplest: “the philosophy / That promised to abstract the hopes of man / Out of his feelings” (1805 text, X.807-09) appealed because it substituted reason for emotion. The writers of Gothic fiction—“Monk” Lewis and Ann Radcliffe, in particular—found a different escape from sensibility; they gave their readers the horrors of Catholicism and superstition, but created characters with enlightened Protestant intelligences to experience, analyze, and often even explain the terrors. Another group of novelists, the English Jacobins, wrote fiction with sensational plots in order to reach their readers’ heads through their hearts.

We must see Mary Wollstonecraft in this context, as a writer and thinker trying to patch up the split between mind and heart, and succeeding, like most of her contemporaries, only partially. Neither her character nor her background did as much to shape her ideas and her work as the intellectual climate she lived in. It is not a criticism to say that she was a creature of her age; so were Fanny Burney and Ann Radcliffe, William Godwin and William Blake. Like them, Wollstonecraft was challenged by the artificial separation of thought and feeling. The new editions of her work reveal both what she achieved and what she struggled against. The confusions of her less successful efforts make them interesting even in failure.

begin page 59 | ↑ back to topMary, A Fiction (1788)—actually a glamorized autobiography—was Wollstonecraft’s second publication. (The first was Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, published in 1787.) With no real interest in characterization or setting, dialogue or action, she pushes her story along in short chapters of flat, undeveloped narration. The heroine is supposed to have “thinking powers” (p. xxxi), but after every effort to act according to considered principles of virtue and humanity, she collapses into self-pitying grief. Separated from a despised husband, deprived by death of the woman and man she most loves, Mary settles in the country to practice “benevolence and religion,” and to take comfort in the knowledge that “[h]er delicate state of health did not promise long life” (p. 68). Having inherited the values of her age, Wollstonecraft may have feared that Mary would lose the reader’s sympathy if she thought a little more and felt a little less.

The same weakness damages The Wrongs of Woman: or, Maria, the novel that Wollstonecraft was working on when she died and that her husband William Godwin published in her Posthumous Works (1798). Mary had been written just before she lost her position as a governess and began to support herself by writing; The Wrongs of Woman was written nine years later, at the end of her career. Maria is stronger, braver, and wiser than the miserable Mary. The writing is more skillful, too, with a group of first-person narratives giving some life to the single-minded pursuit of didactic points. And the novel’s scheme is far more ambitious: drawing not only on her own experiences and her family’s but also on a wide range of reading, Wollstonecraft shows how men legally rob women, tyrannize over them, force them into prostitution, take away their children. She tries to shock her audience, and to a certain extent she succeeds. The heroine defends her lover when he is tried for having seduced her; she argues that no adultery took place because her husband by his cruelty, degeneracy, and greed had forfeited his right to her loyalty. But there are suggestions that Maria’s passion for her lover is not the virtuous impulse of a generous heart but only sentimental self-delusion: “ . . . pity, sorrow, and solitude all conspired to soften her mind, and nourish romantic wishes, and, from a natural progress, romantic expectations” (p. 98). One version of the notes for completing this unfinished work reads: “Divorced by her husband—Her lover unfaithful—Pregnancy—Miscarriage—Suicide” (p. 202). But a conclusion along these lines would have made Maria entirely the victim of men’s deceit. Wollstonecraft was too much a product of the Age of Sensibility to create a heroine who was blameable for letting her heart control her head. Maria’s emotional susceptibility was, like Mary’s, an essential part of her virtue. In her fiction Wollstonecraft could not find a substitute for the begin page 60 | ↑ back to top sentimental belief in the value of feeling for its own sake. Mary and The Wrongs of Woman thus have less interest for readers of fiction than for students of the social and intellectual history of the late eighteenth century. What is striking about both works is the way in which Wollstonecraft willingly sinks her heroines in a morass of feeling.

Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796) is similarly interesting for what it is not. The most impressive thing about the volume is probably its origin in the journey to Scandinavia that Wollstonecraft made, accompanied only by her one-year-old daughter and a French nursemaid. She went on business for her American lover, Gilbert Imlay, the baby’s father. His infidelity had driven her to attempt suicide in the spring of 1795, and he sent her to Scandinavia that summer as a distraction. His plan didn’t work, for soon after her return she made a second attempt and very nearly succeeded.

The Letters from Sweden were addressed to Imlay but written for publication. The book reveals Wollstonecraft at her worst, trying to impress two different audiences—her lover and the book’s buyers—with two different things, her sensibility and her intelligence. She struggles to show how seriously she thinks and how tenderly she feels: “Amongst the peasantry, there is . . . so much of the simplicity of the golden age in this land of flint—so much overflowing of heart, and fellow-feeling, that only benevolence, and the honest sympathy of nature, diffused smiles over my countenance when they kept me standing, regardless of my fatigue, whilst they dropped courtesy after courtesy” (p. 12). This letter, written the day after her landing, shows her straining to utter universal truths about the “peasantry”; at the same time she expresses the warmth of her disposition, thus letting Imlay know what a loving heart he is throwing away. At one point she announces, “I am persuaded that I have formed a very just opinion of the character of the Norwegians, without being able to hold converse with them” (p. 78), and she smugly consoles herself for not knowing the language: “As their minds were totally uncultivated, I did not lose much, perhaps gained, by not being able to understand them” (p. 79). She seems to be a combination of Marianne Dashwood and Elizabeth Bennet’s priggish piano-playing sister Mary. On the occasions when she forgets to be at once an unusual woman, who reasons vigorously, and an ideal woman, who feels strongly, she writes better: “A mistaken tenderness . . . for their children, makes them, even in summer, load them with flannels; and, having a sort of natural antipathy to cold water, the squalid appearance of the poor babes, not to speak of the noxious smell which flannel and rugs retain, seems a reply to a question I had often asked—Why I did not see more children in the villages I passed through” (p. 33). But the letters do not often give us what they give us here, a vivid impression either of what she saw in Scandinavia or of the person who saw it.

A more interesting woman emerges from the private and unpretentious correspondence published in Godwin & Mary Of the 151 letters—106 published whole or in part for the first time in this edition,

begin page 61 | ↑ back to top a reprint of the 1966 original—only 42 are Godwin’s. The correspondence is largely an exchange of invitations before meetings and of explanations after them. (There are a great many explanations here.) Since Godwin and Wollstonecraft maintained separate lives even after their marriage, the correspondence takes them from the beginning of their love affair, in July 1796, right up to the birth of their daughter on 30 August 1797, ten days before Wollstonecraft’s death. While few of the letters are interesting by themselves, the whole sequence lets us watch an unusual understanding develop between the thirty-seven-year-old Wollstonecraft, who had been rejected by her lover, and the forty-year-old Godwin, who had just been turned down by another woman. Even the circumstantial details of life that are missing in Wollstonecraft’s fiction appear here: “I was splashed up to my knees yesterday, and to sit several hours in that state is intolerable. . . . [I]t snows, so incessantly, that I do not know how I shall be able to keep my appointment this evening. What say you? But you have no petticoats to dangle in the snow” (pp. 60, 62). Easily offended and depressed, subject to feelings of neglect and fits of jealousy, Wollstonecraft was capable of undemanding affection: “I wish you, from my soul, to be rivetted in my heart; but I do not desire to have you always at my elbow—though at this moment [Godwin had left London three days earlier] I did not care if you were” (p. 83). She manages to explain her excessive sensitivity: “One reason, I believe, why I wish you to have a good opinion of me is a convictionAnd that, finally, is the reason for the success of her masterpiece, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792): she had a clear sense of herself and of her audience. Repetitious and unsystematic the work may be, but it is also compelling. The very evidence that she wrote it rapidly is proof of the strength of her mind as well as of her feelings; as she said in the Letters from Sweden, “we reason deeply, when we forcibly feel” (p. 160). Her rhetorical ploy works: “ . . . frankly acknowledging the inferiority of women” in their oppressed condition, she argues “that men have increased that inferiority” (p. 119), making them unnecessarily weak, stupid, and frivolous. After attacking Rousseau and others who theorized about women’s education, she sets forth her own notions: that begin page 62 | ↑ back to top

women should exercise their minds and bodies in youth as boys do, and should share responsibility for the management of their homes in adulthood. The latter argument is not unliberated, for she believed domestic occupations offered men as well as women the best chance to be happy and virtuous. She tried not “to leave the line of mediocrity” (p. 138) and therefore talked about the lives of ordinary people, believing that the talented of both sexes would seek other kinds of achievement if they were free to do so. In The Rights of Woman she does not over-simplify as she does in The Wrongs of Woman: if women are the victims of men, whose bad laws, bad education, and bad religion stifle them, women are also more or less willing collaborators in their own degradation.Only near the end of the work does Wollstone-craft mention political equality: “I may excite laughter, by dropping a hint, which I mean to pursue, some future time, for I really think that women ought to have representatives, instead of being arbitrarily governed without any direct share allowed them in the deliberation of government” (pp. 259-60). Energetic and confident in developing the arguments that interest her, she sounds uncharacteristically weak, hesitant, and apologetic here. In fact, she was more concerned that women should learn than that they should vote, and she was more eager to see them increase their power in the family than in the state. She was wiser than she could have known, for the equality she cared about turns out to be the equality that matters, and the right to vote has not been the answer that women hoped it would be.

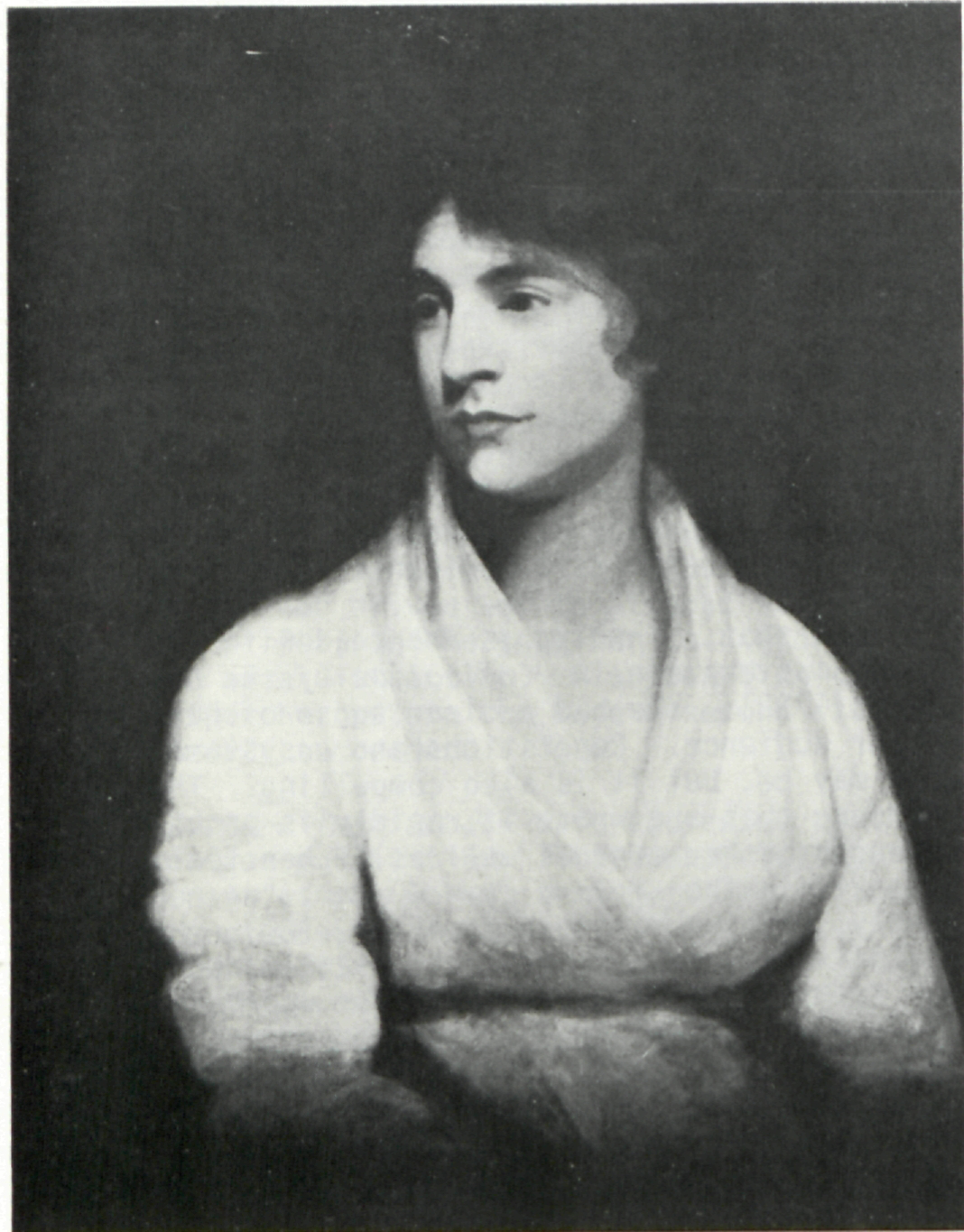

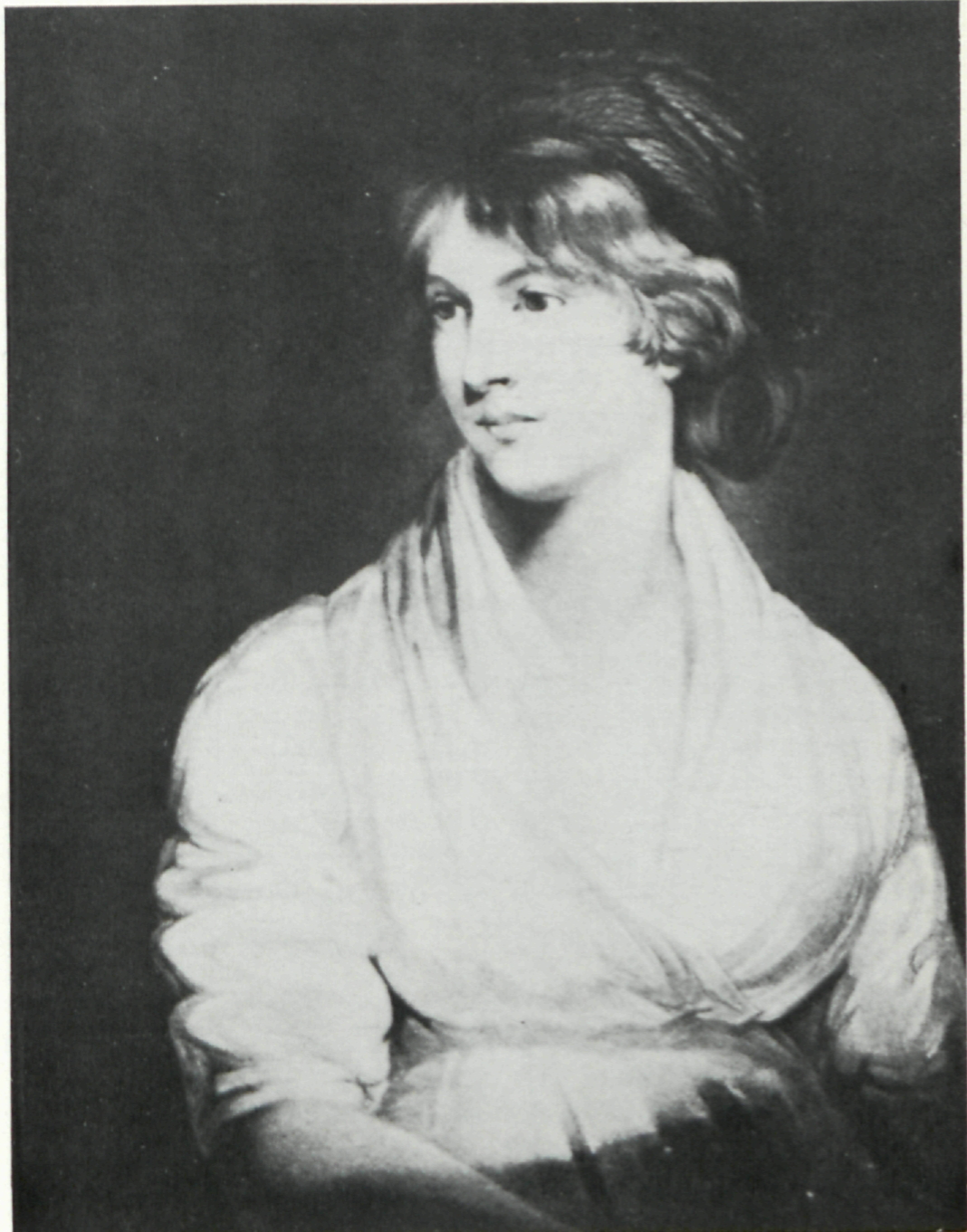

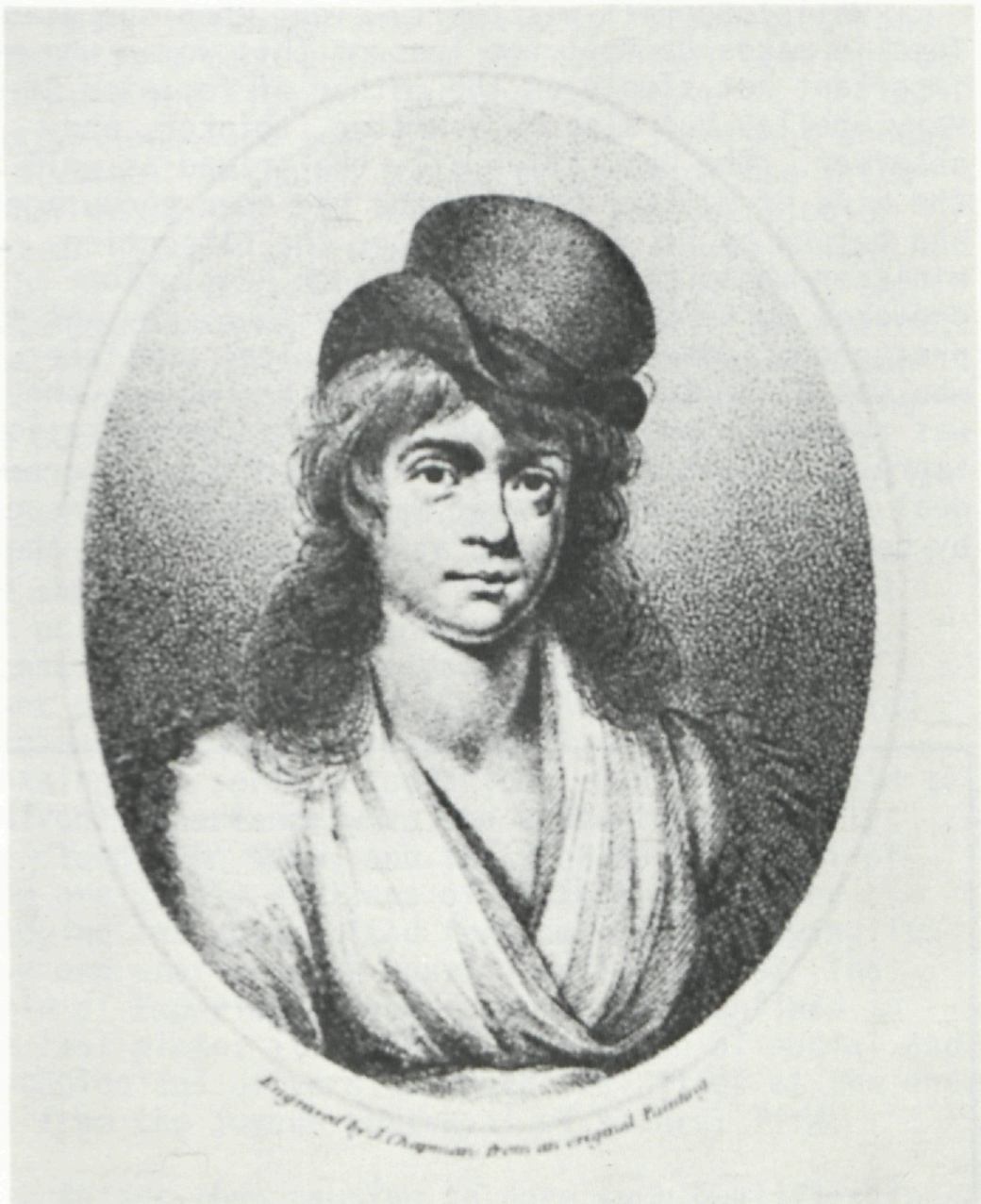

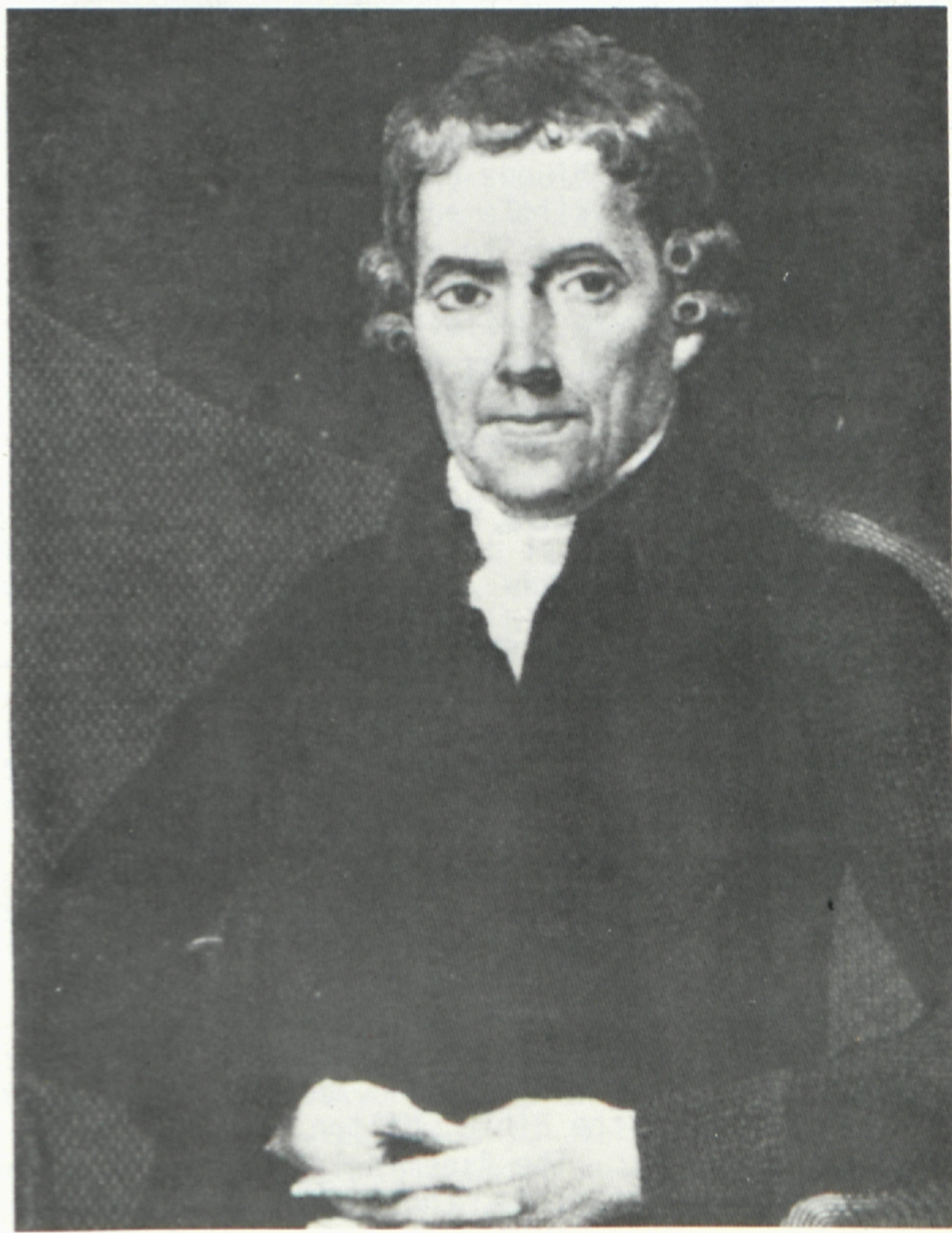

The Vindication remains readable because Wollstone-craft saw the problem so clearly; she recognized that political inequality oppressed women less than the belief in what she called “sexual virtues” (p. 139)—qualities, like delicacy or courage, that are considered merits in one sex but faults in the other. Virginia Woolf’s opinion of the Vindication—that its “originality has become our commonplace” (The Second Common Reader, pp. 143-44)—is probably wrong. The work retains the freshness of an active mind’s enthusiastic encounter with a brand-new idea; the chance to say something truly original freed Wollstonecraft from sensibility, at least temporarily.The Vindication is worth reading, and this new edition is welcome. Miriam Brody Kramnick provides a helpful introduction that places Wollstonecraft’s achievement in its various historical contexts; the notes, by contrast, are only adequate. Gary Kelly, editing the two pieces of fiction for the Oxford English Novels, supplies the full and enlightening notes we have come to expect from that series, and his introduction makes the best possible case for both works. Without minimizing their limitations, he sees what Wollstonecraft’s intentions probably were and suggests that the stories have a coherency of purpose, whatever they lack in execution. The editor of Godwin & Mary, Ralph M. Wardle, published a biography of Wollstonecraft in 1951. His beautifully meticulous handling of the letters transforms these fragmentary materials into a satisfying, readable whole; there is an excellent, brief introductory essay as well as full and enlightening notes and even a fine index. The Scandinavian begin page 63 | ↑ back to top letters are not so well edited. Carol H. Poston’s introduction exaggerates the merits of the letters themselves, and her notes are more often gratuitous than useful. She includes a map of the itinerary but makes no further effort to sort out the jumble that Wollstonecraft’s topographical and chronological vagueness creates. While the book is nicely illustrated with engravings that were not in the original edition, these are not identified.

Wollstonecraft’s life was eventful enough to be interesting if she had written nothing. She rescued—or kidnapped—her sister from the sister’s husband, leaving behind a five-month-old baby that died within the year. She traveled alone across winter seas to Lisbon to be with her friend Fanny Blood at the childbed that turned into a deathbed, then sailed back to London in worse weather, compelling the captain to rescue the crew from a foundering French ship. She fell in love with the painter Henry Fuseli but was turned down when she tried to persuade his wife to let her live with them, so she went to France in December 1792, in time for the King’s trial and execution, and stayed on through the Terror, an enemy alien but Imlay’s mistress finally returning to London in April 1795. She struggled from the age of eighteen on to support, at different times, her two sisters, her younger brothers, Fanny Blood, and Fanny’s family; her eldest brother, a lawyer who had inherited property from their grandfather, did almost nothing for any of them. At twenty-five she started a girls’ school in which she, her sisters. and Fanny worked, and when it failed, she went to Ireland as a governess in an aristocratic Anglo-Irish family, before she fianlly settled in London, writing, reviewing, and translating. She did not always live by the principles of sense, discipline, and duty that she laid down in the Vindication; her two attempts to kill herself when she had a baby who was dependent on her violated the rules that she said women should live by if they were to act like rational creatures.

Claire Tomalin had a good story to tell, and she tells it sympathetically but critically in The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. It has been told before—several times quite recently—but this life is the most comprehensive. Tomalin tells us a great deal about the people who surrounded Wollstonecraft in England and France, fills in the political and social background fully and vividly, and discusses Wollstonecraft’s influence after her death. This breadth allows Tomalin to give convincing factual explanations of Wollstonecraft’s actions and feelings, and to avoid psychologizing. Tomalin seems to tell all that can be known about Wollstonecraft’s life. There is one issue that Tomalin does not discuss, however: the suggestion made by Robert R. Hare that Wollstonecraft and not Imlay wrote the two books published as his.1↤ 1 Hare presented his case at length in “The Base Indian: A Vindication of the Rights of Mary Wollstonecraft” (M.A. theses Univ. of Delaware 1957), and later summarized his arguments in the introduction to his facsimile edition of the novel, The Emigrants, which he published with both Wollstonecraft’s and Imlay’s names on the title page (Gainesville, Fla.: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1964). If the works were actually hers or collaborations between her and Imlay, that would not only affect the chronology of their relation but also alter our view of both of them, making him a still less significant character and her the author of a third novel and a successful travel book. Hare’s arguments deserve to be answered, and Tomalin’s opinion would be worth having.

begin page 64 | ↑ back to topWollstonecraft was thirty-eight when she died. Tomalin makes us feel the loss of this woman who was important not simply as the mother of feminism or of Mary Shelley but also as a writer, thinker, and observer. She was, after all, the friend as well as the wife of William Godwin; she had been encouraged and helped by Dr. Richard Price, the Dissenting minister whose sermon on the French Revolution provoked Burke to begin his Reflections; she was the protegée of Joseph Johnson, the Radical publisher, who got Blake to illustrate two of her works; she was read by Blake and Southey, and her conversation impressed Coleridge and Lamb. She achieved a great deal in a working life that was shortened at one end by poverty and lack of education as well as at the other by early death. She was prevented from achieving more by her sex, which limited her activity to writing although her real talents were probably for some other field—politics, education, medicine—then closed to her. Yet she managed to write a book that was nearly two hundred years ahead of its time; not many men or women without her weaknesses or disadvantages have done that much.