REVIEWS

Raymond Lister, ed. The Letters of Samuel Palmer. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974. 2 vols., 1123 pp., $80.00.; Raymond Lister. Samuel Palmer A Biography. London: Faber & Faber, 1975. 299 pp., $12.95.

It is now over fifty years since Samuel Palmer’s son organized the exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum from which the general interest in Palmer dates. The artist was presented then as a “Disciple of William Blake,” and that loose description has stuck. Geoffrey Grigson’s important account, Samuel Palmer the Visionary Years of 1947, was constructed on the foundation of that description, and even David Cecil’s brief but comprehensive biographical sketch in Visionary and Dreamer of 1969 lays the same firm emphasis. There has been much praise of Palmer—or at least of certain aspects of his work—but no great willingness to accord him any role other than that of “disciple.”

Palmer himself unintentionally encouraged this approach. The very word “disciple” with its New Testament overtones perfectly evokes the passionate religious wellspring of his art. He spoke of Blake with fervor as one of the great spirits of history, morally as well as artistically excellent, in a class apart. The intensity of response that Blake characteristically showed is apparent also in Palmer’s best work, and Palmer indicated that he felt such a response to be in some way “Blakean.” Yet his art is in almost every way of a different kind from that of Blake, and, in sum, is by no means the work of a “follower,” either in its content or in its technique. We have long been in possession of the circumstantial evidence necessary to form a judgment of its real character, for not only have we had access to much of his output, but A. H. Palmer’s illuminating Life and Letters has been in print since 1892. Now that Raymond Lister has edited the complete correspondence, still more of the essential material is easily available.

For Palmer wrote a great deal about both the theory and technique of his art. He was a remarkably gifted prose writer, with a natural sense of rhythm, of rhetoric, of imagery, and a voluminous store of quotations. There were moments in his life when he contemplated turning to literature for his livelihood, and he would have been well fitted for such work. “It is very much easier to give vent to the romantic by speech than by [painting],” he said. Accordingly, we have a vivid picture of those aspects of the world and those ideas that moved him, or repelled him, and can trace accurately in his letters the genesis of particular images in his pictures from particular experiences in his travels. There is also a great deal of information about his methods of working, especially after he became associated with Philip Gilbert Hamerton, editor of the art magazine Portfolio, who got Palmer to write for him on the use of watercolor and on etching. There are letters to pupils that give detailed directions as to how to create special effects in watercolors, and long letters to his patron Leonard Rowe Valpy expounding his personal interpretation of natural phenomena as the substance of art.

The mass of correspondence from Italy during his honeymoon, which Mr. Lister prints with all Hannah Palmer’s contributions, charts not only personal matters like the gradually opening rift between Palmer and his interfering father-in-law, John Linnell, but the whole slow, marvellous dawning of the Italian experience on Palmer’s sensibility—the realization of “certain types of landscape only found in perfection in Italy,” as he said. It was for him “a course of purgation—getting a quantity of rubbish and confusion out of my mind.” These reactions seem odd in the hermit of Shoreham, the quintessentially English rural visionary. What need had Palmer of Italy, any more than Blake? Yet Blake esteemed Michelangelo above all artists, and even at the very beginning of the Shoreham period, Palmer was dreaming of Italy and the great works of the Italian begin page 151 | ↑ back to top

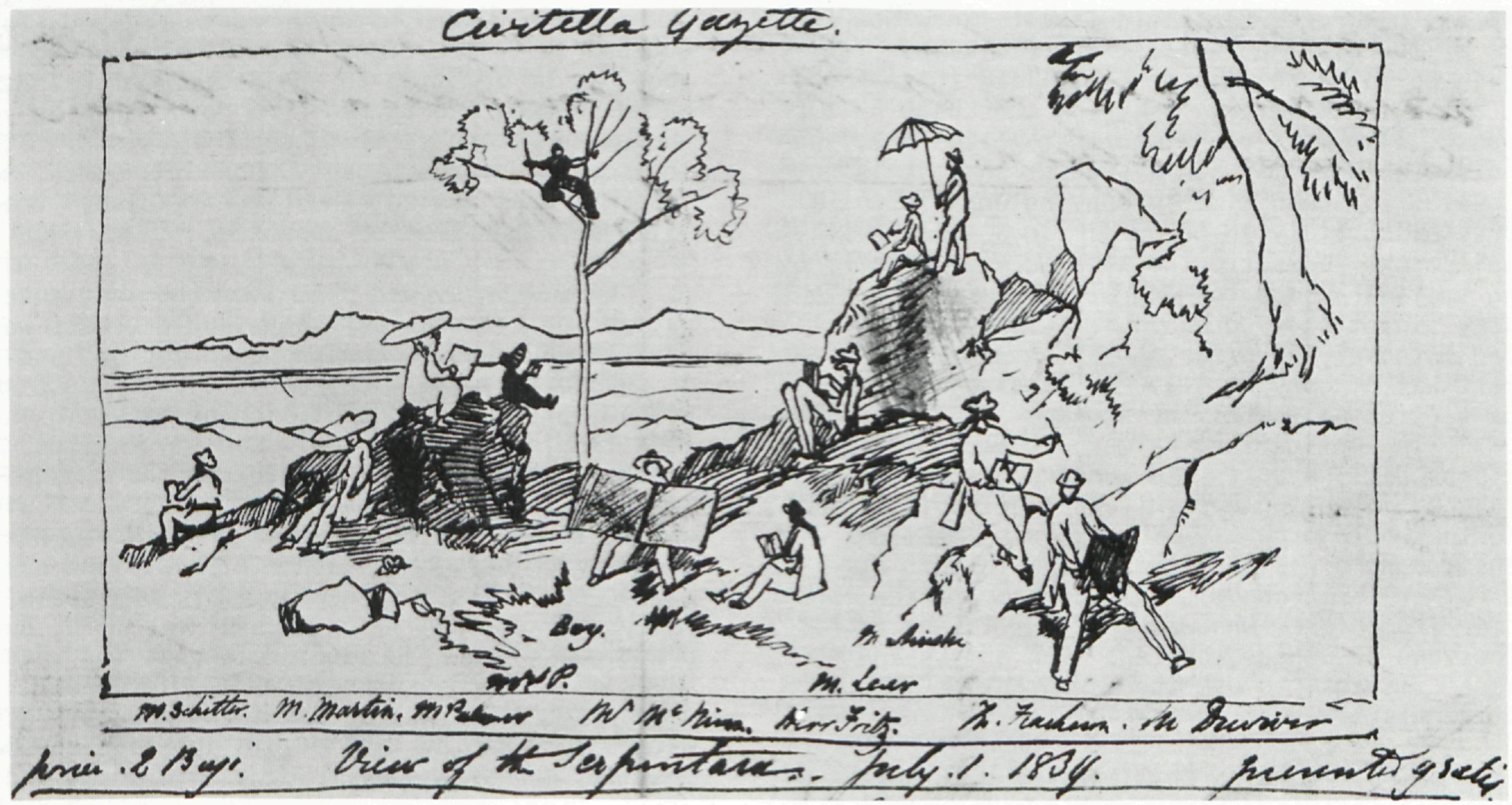

Shortly after this expedition, Hannah wrote home from Civitella: “Our life now is so thoroughly that of working people that not knowing the days of the week we rose last Sunday morning in haste at 4 oclock in the morning, got all our sketching apparatus packed up for going down into the valley to our daily work thinking it was Saturday; not [sic; nor?] should we have been the wiser had not Mr Lear, an artist here who keeps a journal, told us. Mr Martin works as hard as anybody.” Palmer, under the same date, wrote: “Yesterday and today—for the first time in our travels I have been wholly unable to work which is very miserable as Civitella abounds so with beautiful foreground studies that our time being short not a moment should be lost. Of Mr. Martin I am sorry to be obliged to give a much worse account. In spite of every precaution against sun etc. he has suffered every fortnight since coming to Rome—with sickness at the stomach—so as to be for several days unable to eat— . . . at Subiaco we attributed it to the intense heat—but the air is much cooler here and Mr. M. never sits late in the sun—nor without an umbrella at any time.” This may explain the large, wide-brimmed hat that Martin wears in the drawing.

The sketch is a delightful insight into the lives of Palmer and Hannah and their friends during the Italian tour, and is strikingly similar not only in its humor but in technique to the pen drawings of Lear himself. It includes almost certainly the least sympathetic portrait of Palmer to have come down to us; but a portrait at which, no doubt, Palmer would have laughed heartily. (A.W.)

And so Palmer moved on, impelled by a spirit of his age that exercised remarkably tight control over him, considering that he was in almost every respect a reactionary, one who cringed away from the present, who sought to hide from the evils of “progress,” who mistrusted science and was terrified of the increase of agnosticism, tight lacing, urban sprawl, pollution and public schools—a pattern of the conservative mentality past and present. As he grew older, indeed, his very religion, the motive force behind his greatest art, became prosy and prudish, the agent of repression to his children and the subject of endless discourses that we should now label typically “Victorian.” Mr. Lister betrays an odd lack of understanding of the educational methods of the period when he castigates Palmer for feeding his three-year-old son on the Bible, Bunyan, and Sandford and Merton. Palmer’s advocacy of a bowdlerized Shakespeare is disconcerting, however, given his strong feeling for literature, and his acquaintance with Blake’s own unselfconscious modes of expression. Like many other talented artists of his time, he succumbed to the stifling climate of general opinion (one almost senses that he knew it, in his constant complaints about the unhealthy atmosphere of London), and his art suffered like everything else. When in 1859 he wrote “I seem doomed never to see again that first flush of summer splendour which entranced me at Shoreham,” he expressed the same nostalgia for his own creative youth that Millais was to feel when, standing in front of one of his early canvases during a retrospective show in 1886, he was moved to tears by the contrast between that and his current work.

The comparison with Millais, however, points up Palmer’s real distinction from the successful Millais’ world of fashionable and glib virtuosity. He never had any success as a “society” painter, and although in a sense he never wished it, we catch an unmistakable note of frustration and puzzlement when, in Rome, he watches his friend Richmond moving in fashionable circles while he and Hannah are left out of the social life of the city, and are given no commissions. When he returned to England, fully equipped with the right subjects, he waited many years to be admitted to the Society of Painters in Water-Colour, and there is no doubt that he very much wanted to belong to that body of artists. It is in the context of the Society, and of another, more informal institution, the “Etching Club,” that his later work can best be assessed.

It was an avowed object of the instituted watercolor artists that they should create works of high seriousness in their chosen medium, and indeed it was to facilitate the exhibition of such works, without the unfair competition of oil-paintings, that they had founded their society in 1804. They treated subjects that ranged from the kind of picturesque landscape that is most associated with watercolor to the grandest figure pieces, historical or mythological, and elaborately detailed scenes in exotic countries, especially Italy and Spain. Palmer worked in oil for much of his life, but in practice showed a decided preference for watercolor, especially in the second half of his career. He employed the methods of enriching and strengthening watercolor used by many of his colleagues: bodycolor made its appearance early on at Shoreham, and much of his later work was “a kind of Tempera” as he said in a letter of 1873—which recalls, perhaps, Blake’s use of that vehicle. Whatever the details of his method, he strove to load his watercolors with a density of feeling and a richness of detail that was precisely analogous to the intentions of the Society. What we recognise as distinctive is the continuing strain of the visionary insight into rural life that was so active in the 1820s; if feebler and more rarefied, that fervid instinct for the inwardness of the countryside and the religious force of its beauty informs much of his late work, and makes him, in fact, one of the finest of the Society’s artists.

The technical range and power of watercolor at this period undoubtedly owed much to the example of Turner, who was an inspiration to the founders of the Society, even though by virtue of his membership of the Royal Academy he could not belong to it. What emerges very clearly from the letters of Palmer is that, while Blake was never superseded as his spiritual guide, Turner became a technical and practical inspiration of the greatest importance. The effect on him of Turner’s Orange Merchant of 1819 is often noted; but that large marine painting can hardly have had much practical bearing on Palmer’s work. Even the atmospheric little watercolor studies that date from about that time are hardly “Turnerian” in any serious sense. But the meticulous precision with which he constructed his later watercolors can have been based on no other master. References to Turner’s watercolors are frequent in Palmer’s writings; it is true that he asserts that Claude is the greatest of all landscape painters—but then Turner would himself have sympathized with that view; and Turner, he observed, “had the faculty to which Claude never appeals in vain.” While he was in Italy, he often saw landscape through Turner’s eyes, and he indicates that Turner conveyed the poetry of the scenery, just as he wished to do himself: “ . . . what beautiful country must begin page 153 | ↑ back to top be here in summer it is difficult to conceive—the lights of Canaletti are like the literal versions, and Turners more like the poetical . . . .” He notes that Turner was very fond of the Val d’Aosta, and that he did not like Subiaco; he inquires eagerly after “the fine collection of Turner’s drawing at Mr. Windus’s”;[e] he often asks about the pictures Turner was showing at the Academy, and once comments on the “corruscation of tints and blooms in the middle distance of his Apollo and Daphne”—which “is nearly, tho’ not quite so much a mystery as ever,” and adds “I am inclined to think that it is like what Paganini’s violin playing is said to have been; something to which no one ever did or will do the like.” In the same place he says “I would give anything to see some of Turner’s best water-colour drawings now; and if I am preserved to come home, shall beg the favour of Mr Daniel to get me a sight of a most splendid collection . . . .” He observed that “the plenitude of light [in Italy] gives a coolness of shadow and a glow of reflection of which we have no notion in England. No one has done it but Turner and he makes the shadows and reflected lights much lighter than in nature.” He carried this enthusiasm home with him, and waited many years in anticipation before he had access to the artist’s bequest, which was at first exhibited in the South Kensington Museum at Brompton: “As soon as the Turners come,” he wrote in 1859, “I shall be out enough you may be sure, in the direction of Brompton.” Turner crops up in Palmer’s letters as a figure whose every action and thought he has studied with love: he adjures his correspondents to look at Turner’s prints for particular subjects; to visit the Fawkes collection of Turner’s drawings at Farnley Hall; he notes that Turner knew Margate well, and that a house near Turner’s was haunted. In short, there are ubiquitous indications that Palmer knew much about the life and work of Turner and had “adopted” him as a touchstone of excellence in the field of contemporary landscape.

This may seem self-evident, given Turner’s preeminence. But the significance of such a respectful regard in Palmer is far greater than that of the mere professional esteem of the mediocrities in the Water-Colour Society. In Palmer’s later work, we sense the striving to achieve what Turner achieved of enhanced and rapturous union with nature; Turner was not at all like Blake, but in his way he was a visionary artist, and as a practical example for Palmer was far more immediately relevant. Mrs. Hamerton recalled Palmer’s conversation as being spiced with “anecdotes of Turner and Blake,” and this coupling has never, I think, been given its proper weight. Of all the ambitious watercolorists who were influenced by Turner, Palmer was perhaps the only one with the intensity and honesty of vision to benefit from more than his technical lessons. Hence, he is a landscape artist of real distinction in a generation of somewhat shallow virtuosos. Judged by the standards of his youthful achievement—his own standards—he did not maintain his early quality; but judged by theirs, he was a conspicuously fine exponent of the grand watercolor style of the period.

In his biography, Mr. Lister does not explore Palmer’s achievement in any depth, contenting himself with a reiteration of the conventional summary of his art, and reaffirming what he himself made clear in his book on the etchings (1969), that it was as a printmaker that Palmer, late in life, found himself once more. He concentrates on the personal aspects of Palmer’s life, giving a full account of the long-drawn-out quarrel with Linnell, though he follows A. H. Palmer’s conclusions in apportioning the blame pretty evenly on both sides, while the letters strongly suggest that Palmer was consistently well-intentioned and gentle in his responses to a very difficult man (and the tone of Albin Martin’s correspondence with Linnell—printed here when subjoined to Palmer’s own—is quite as obsequious; which suggests that Palmer was not unusual in being somewhat cowed by his father-in-law). He recounts the appalling tragedy of the deaths of Palmer’s two eldest children; but it is not difficult to present them in their full horror, since Palmer himself put his anguish only too painfully into words. Oddly enough, Mr. Lister offers no explanation for the death of Mary, Palmer’s daughter, in 1847, although in the Letters he quotes a statement by Hannah Palmer that the little girl had been poisoned by a weed she had picked and eaten. All in all, considering the range of documentary material to which he has access, he does not present a picture that differs essentially from the existing one; and he fails to narrate the story in a coherent or interesting way, flinging scraps together as best he can, without giving them an overall and purposeful form. The main facts are, for the most part, there; but Grigson and Cecil make better reading.

The editing of the letters is handled with much greater success. Mr. Lister has assiduously transcribed, ordered and annotated a mass of confused material, and makes very good sense of it. He has identified a large proportion of the people mentioned, and pinpointed most of the multitudinous quotations. His footnotes are helpful and plentiful. I would suggest that he has erred in identifying the “West” to whose “recollections from the old Masters” Hannah Palmer refers on 8 April 1839, and who also appears in a note of 17 February 1829 as Benjamin West, P. R. A: this is surely Joseph West, the watercolor copyist who made transcriptions of pictures in the Louvre and other collections in a style influenced by Bonington. I think, too, that it is mistaken to identify the phrase “The thing that is not” as a quotation from Julius Caesar, Act v, scene iii: it is surely the Houynhmhm paraphrase for a lie, in the fourth book of Gulliver’s Travels, which we know Palmer had read. The letters are very agreeably presented by the Clarendon Press, and Mr. Lister’s system of transcription is on the whole lucid. He eschews the editorial sic, but the printers have not befriended him here, for there are many misprints which can only mislead users of the volumes, who will have no guide as to which are Palmer’s oddities and which the printers’ errors. The editor himself seems guilty of a number of puzzling lapses, as when he transcribes a phrase in a letter of 1839: “inveighed Hannah into the conspiracy” is nonsense as read—the word must be “inveigled”; the misreading is repeated several times. Again, Mr. Lister occasionally interprets lacunae rather oddly: once Palmer ends a letter, after a reference to Heaven, “which[e] that we may ( ) day see together in good earnest is the hearty prayer of . . . Yours affectionately, begin page 154 | ↑ back to top S. Palmer”: Mr. Lister inserts (to) in the gap; clearly (one) is the correct reading. I am not sure that I concur with his expansion of ampersand and contractions such as “affy” for “affectionately,” since he does not always expand “ye” for “the” or “wd” for “would.” How very different Blake texts would look if “&” were invariably treated to editorial expansion! But these are minor inconsistencies in a remarkable feat of careful research and consistent editing which, whatever the merits of the biography, itself makes a book extraordinarily well worth reading for its account of the mind of a pathetic, lonely and pessimistic, yet distinguished man. It is a fit summary of Palmer’s naivety and self-denigration, and of his lifelong earnestness in pursuit of an art which was, as Blake had taught him, at least half divine, that he should sign himself, at the conclusion of one of his last letters, “A blind baby feeling for the bosom of truth.”