article

begin page 178 | ↑ back to topTHE ECHOING GREENHORN: BLAKE AS HEBRAIST

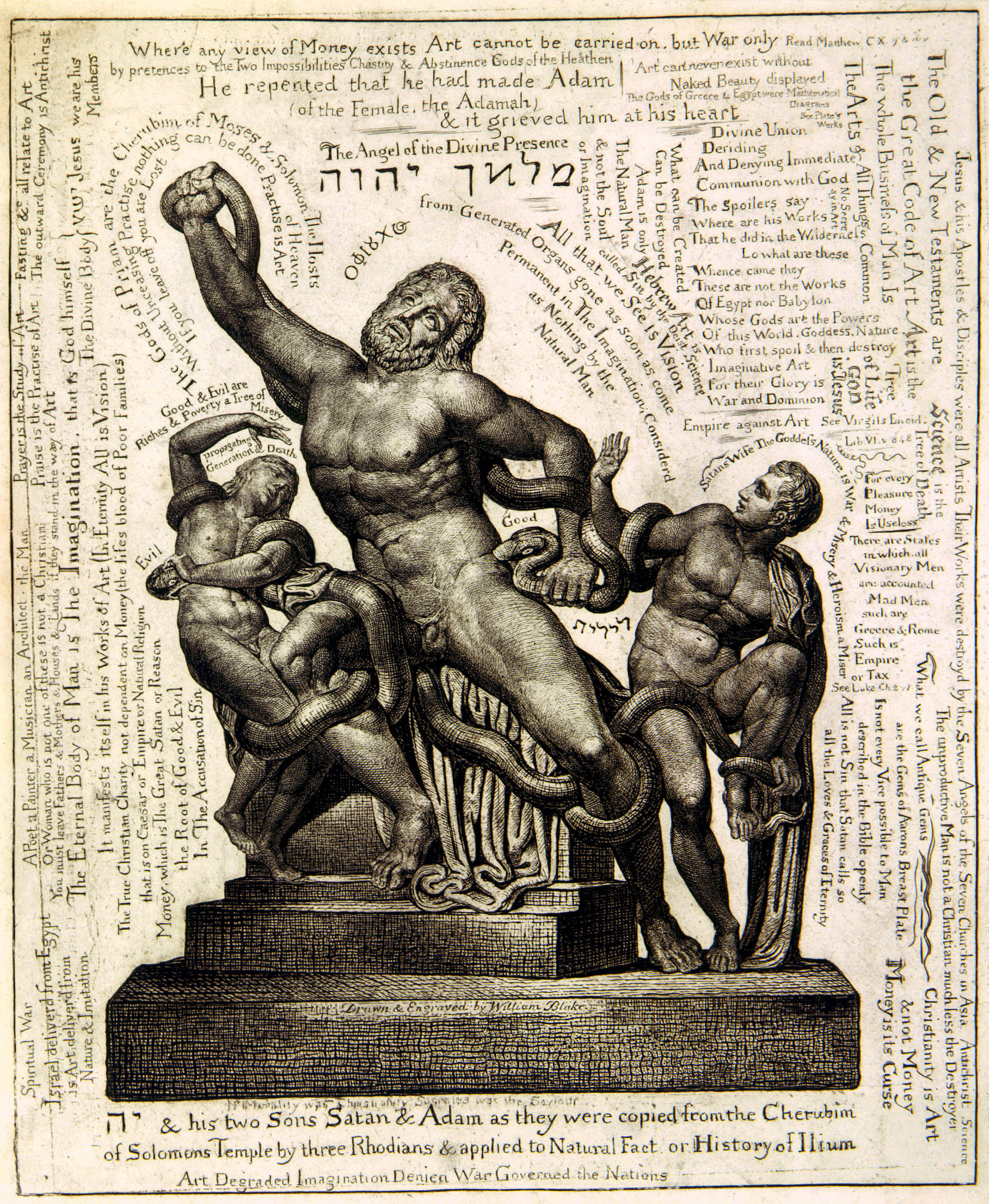

As students of Blake know, “the most formative literary and spiritual influence” on him was the Bible.1↤ 1 Jean Hagstrum, William Blake: Poet and Painter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), p. 48. There is considerable uncertainty, however, about the extent of Blake’s familiarity with the original language of the Old Testament, Hebrew. Although at least eight of his illuminations contain Hebrew inscriptions, “we do not know how much Hebrew Blake had . . . .”2↤ 2 Harold Bloom, “Commentary,” in The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David Erdman (New York: Doubleday, 1965), p. 838. In the thirteen years since Harold Bloom’s acknowledgment, that small island in the sea of Blake scholarship has not, apparently, been covered. I will attempt, then, on the basis of the inscriptions to assess Blake’s knowledge of and facility with Hebrew. Because the irregularities in the inscriptions are so telling, we can focus our attention exclusively on them. If they had been accurate and in a good hand, their evidence would be equivocal. We could not know, in that case, if Blake merely possessed a good eye for copying.

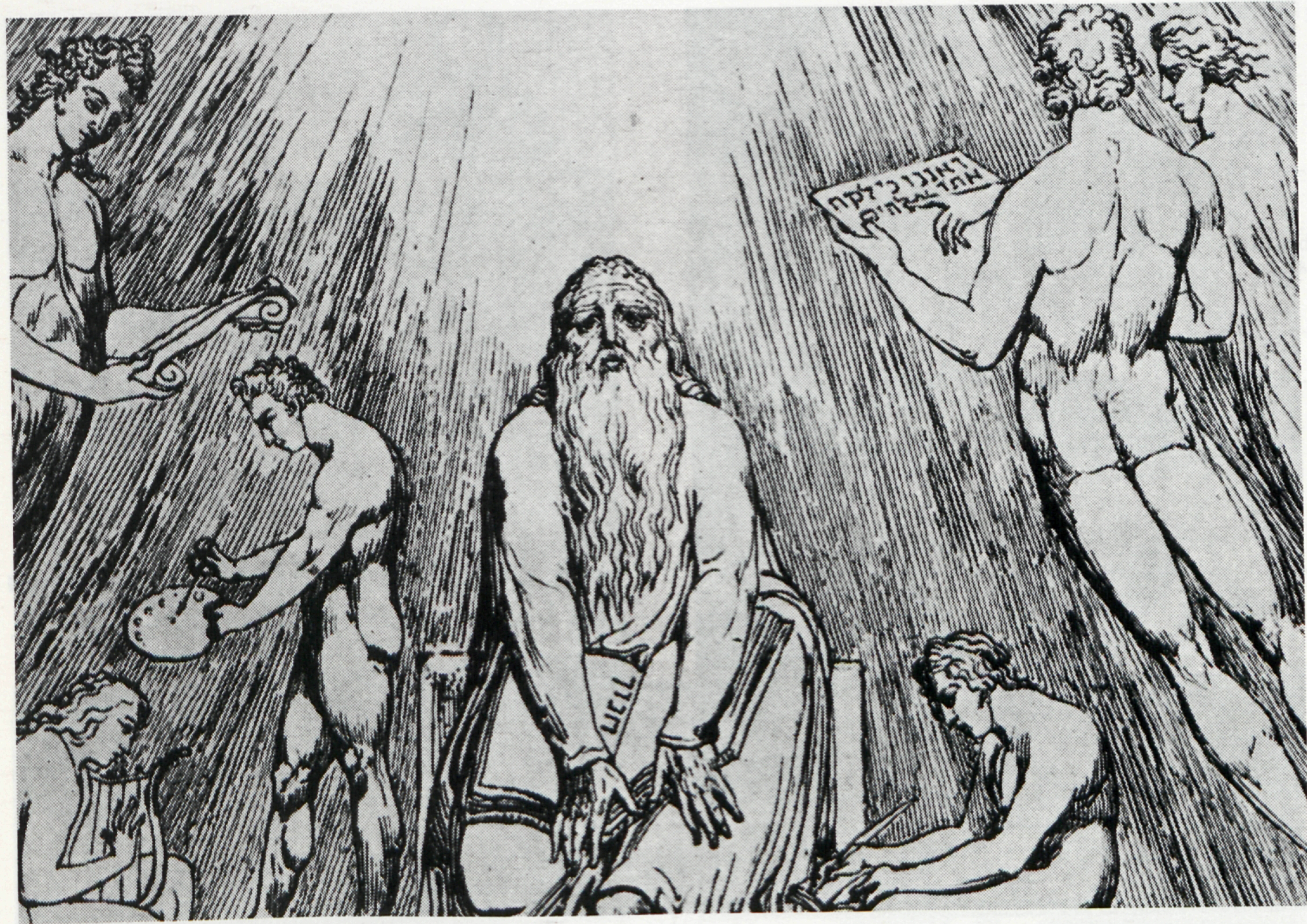

An obvious reason for the uncertainty about Blake’s grasp is that most critics themselves have no Hebrew. One such figure, Mr. A. G. B. Russell, concluded that the subject of Blake’s only lithograph, a bearded “ancient” holding a book inscribed with his name, was “Job in Prosperity.”3↤ 3 Geoffrey Keynes, introductory monograph to Illustrations of the Book of Job, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1935), p. 8.

Only after the ascription had gained general acceptance did someone notice that the name in Hebrew characters identifies the subject of the lithograph not as Job, but as Enoch. “And he was no more because God took him” (Genesis 5:24), the Biblical description of Enoch’s signal death, is being scrutinized by two naked figures on the right side of the composition. A further irony lies in the very name that was missed—for “Enoch” (“Hanokh” in Hebrew) can mean “education.”

Unable to assess Blake’s grasp of Hebrew from internal evidence, Frederick Tatham, an early biographer, relied on circumstantial evidence from Blake’s book collection. Finding Hebrew books “well thumbed and dirtied by his graving hands,” Tatham concluded that Blake had “a most consummate knowledge” of the great Hebrew writers.4↤ 4 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969), p. 41. This highly questionable deduction can be put in its proper perspective with the help of G. E. Bentley, Jr.: “As a source of biographical facts [Tatham’s] Life is of dubious value.”5↤ 5 Bentley, p. 507.

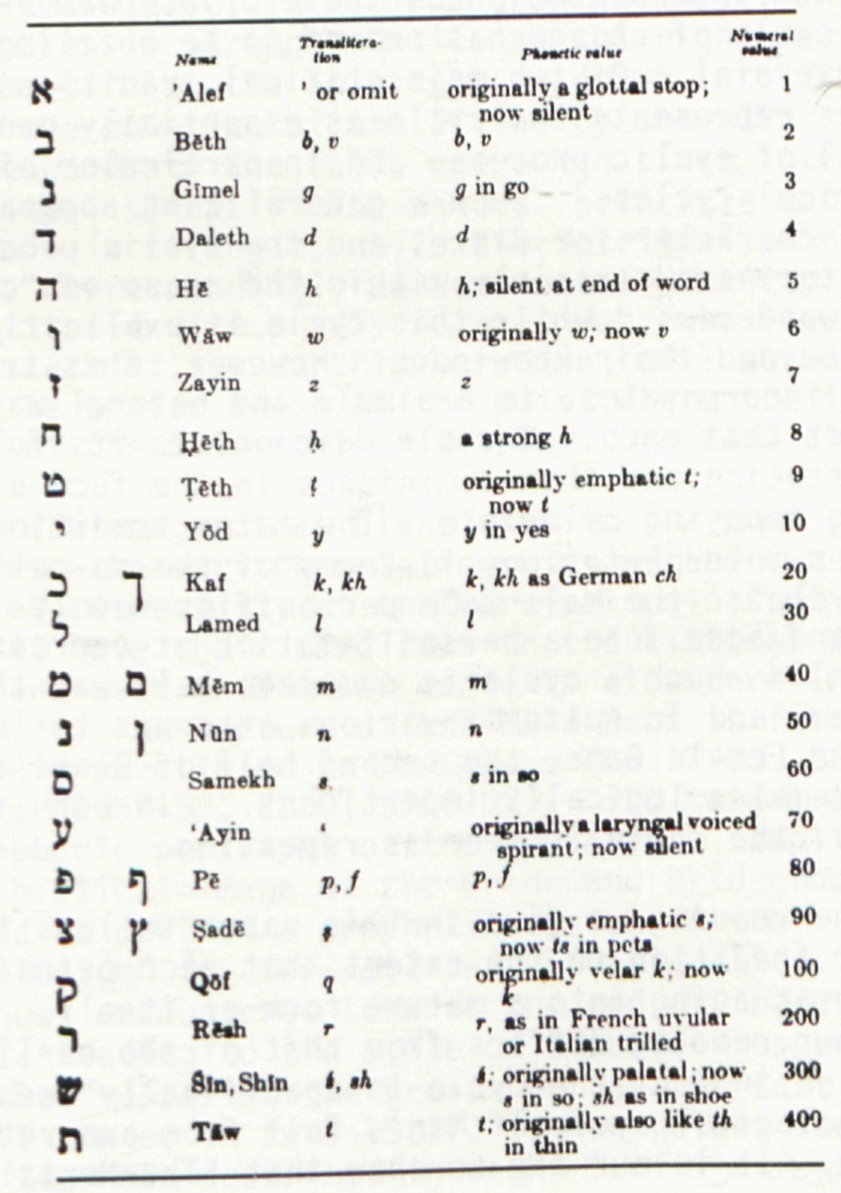

Unfamiliarity with the language seems to be responsible for another disturbing problem in Hebrew-related Blake scholarship. Blake’s lone reference to his Hebrew studies, found in an 1803 letter to his brother James, contains Hebrew characters. They have, however, been printed at least six different ways. In 1921, Geoffrey Keynes printed the series as אבכ (ABK—’alef, bēth,6↤ 6 This character would technically require a dot (dagesh) within it in order to be considered a beth. But in unvocalized Hebrew the dot is not used. I have read other such letters in the same fashion when clearly appropriate. kaf) i.e., “am now learning my Hebrew ABK.”7↤ 7 Geoffrey Keynes, A Bibliography of William Blake (New York: Grollier Club of New York, 1921), p. 451. (Hebrew is written from right to left. For ease of comprehension, however, I have written the English equivalents which follow directly, and then the names of the Hebrew letters, from left to right. An alphabet table is printed with my essay for the reader’s reference.) This meaningless series was replaced by an equally meaningless one in 1927: אידב (AYDB—’alef, yōd, daleth, bēth), four characters instead of three.8↤ 8 William Blake, Pencil Drawings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (Great Britain: Nonesuch Press, 1927), sketch 27. Finally, in 1968 Keynes proposed אבג (ABC—’alef, bēth, gīmel)—a rendering which would put Blake at the beginning of his Hebrew language studies.9↤ 9 William Blake, The Letters of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes, (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1968 [revised edition]), p. 65.

begin page 179 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Mona Wilson, generally regarded as the best twentieth-century biographer of Blake, remains consistent in printing the series as a four-letter group. However, her 1949 rendering, איונ (AYON—‘alef, yōd, wāw, nūn), becomes איוב (IYOV—‘alef, yōd, wāw, vēth) in the 1969 revision.10↤ 10 Wilson actually seems to be returning here to a second reading offered by Keynes in 1927—and abandoned as early as 1956. This latter version, in striking contrast to Keynes’s latest version (ABC), makes Blake a good Hebraist since IYOV, the original name for Job, is one of the most difficult books in the Bible. Who, then, is correct?

By examining a photographic reproduction of the relevant portion of the letter containing Blake’s lone reference to his Hebrew studies, I have found that Keynes’s last variation, אבג (ABC), is accurate. No explanation for Keynes’s forty-seven year delay or for other divergent readings is provided by the difficulty “of mak[ing] out what Blake [actually] wrote before he deleted the manuscript or erased the engraving . . . .”11↤ 11 F. W. Bateson, review of The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David Erdman, New York Review of Books, 28 October 1965, p. 24. It is unmistakably legible, as the reproduction below shows. Elsewhere in Blake’s Hebrew inscriptions, however, there are relatively many obscurities and irregularities. Their special character, in contrast to that of the English ones, suggests that Blake never did master all of the Hebrew ABC’s.

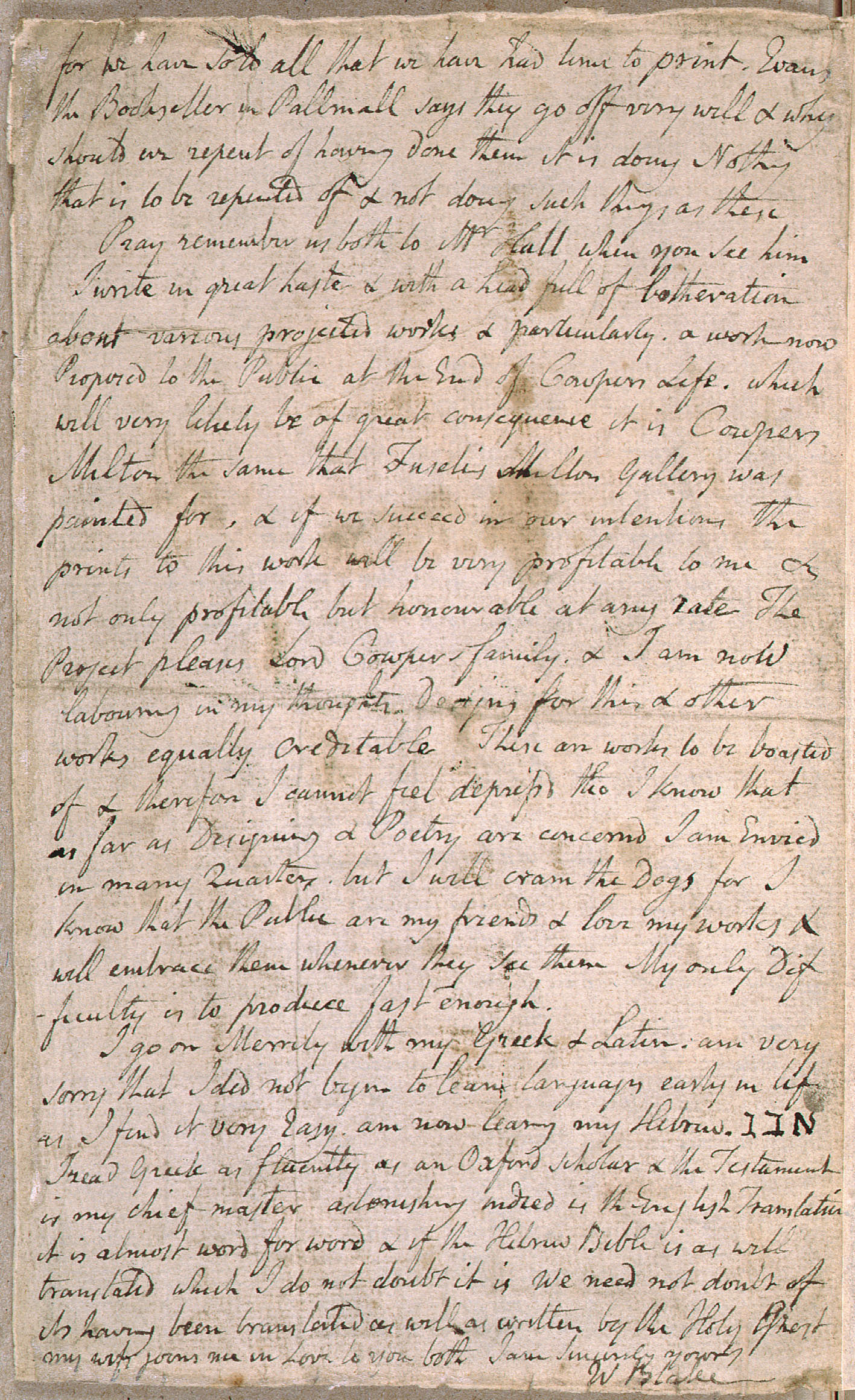

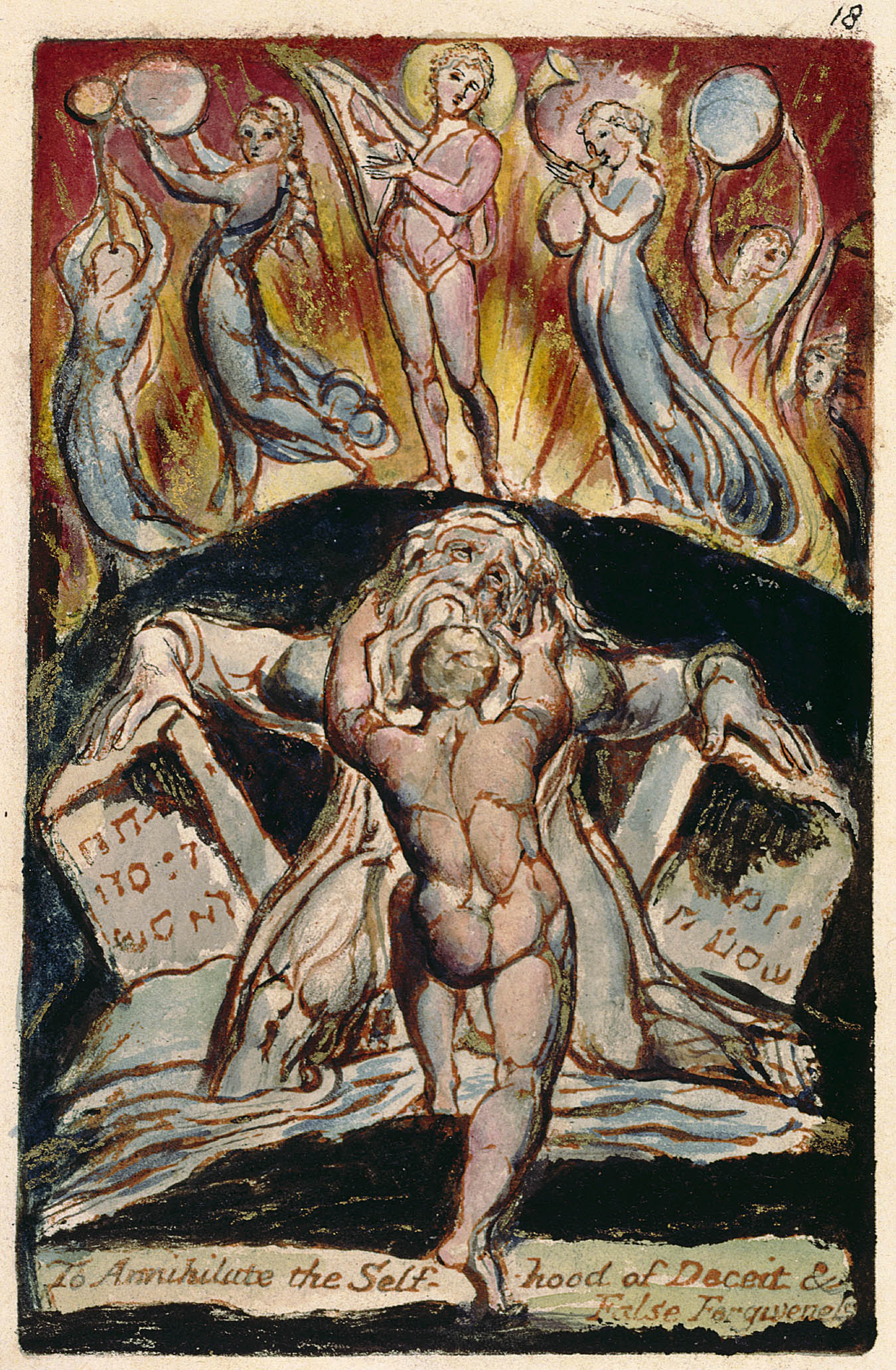

Plate 18A of Milton, which contains “letters so erroneous that it seems impossible to identify or

translate them,”12↤ 12 S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake (Providence, R. I.: Brown University Press, 1965), p. 215. serves as a good starting point. This evaluation by S. Foster Damon was actually make of a 1797 inscription in Night Thoughts. That it applies equally well to this one of 1804 throws into question Damon’s own implication that Blake improved significantly in the years after Night Thoughts. To facilitate an evaluation here, I have included alongside it a typical pair of tablets (a familiar motif in Jewish ceremonial art).13↤ 13 Tablets of unknown origin and date from the collection of The Jewish Museum, New York. Although several letters scrawled on the tablets in Urizen’s hands are identifiable, they do not form, without interpolation, Commandments or abbreviations for Commandments that sometimes run to several sentences. If this plate existed in isolation, one could argue for the appropriateness of the illegibility in that Urizen and the tablets he holds are, to borrow a word from Blake’s caption, in the process of annihilation.Another set of stone tablets of the Law, in “Job’s Evil Dream” from the Butts watercolors of Blake’s Job,14↤ 14 Job, pl. 11. begins to make such a sympathetic view untenable. The last three letters from right to left in the line indicated by Job’s persecutor compose “gave,” incorrectly spelled as נתנ (NTN—nūn, tāw, nūn). The nūn (circled in reproduction), like several other Hebrew letters, requires a different form at the end of a word. It is easily seen that Blake merely repeats the regular nūn (נ). This loose parallel in English may clarify begin page 181 | ↑ back to top the fundamental nature of the error: spelling “jeopardy” with an “i”—“jeopardi”—instead of a “y” because the verb form uses the “ize” suffix (“jeopardize”). Just as the “i” cannot end “jeopardy,” so a regular nūn cannot end נתן. This is not, apparently, the only such error.

One way of explaining this inscription is by positing Blake’s use of a transliteration. Since both regular letters and their final counterparts sound identical, the English (Roman) character would not distinguish them. I have not found evidence of printed transliterations of the Hebrew Bible extant in Blake’s time, but it is possible that his instructor transliterated the Ten Commandments for Blake.

This hypothesis might also explain another “letter interchange” committed in the Milton tablets. On the one in Urizen’s right hand, Blake substitutes a ס (S—samkh) for what should be a ת (S [according to the Ashkenazic pronunciation]—taw). These Commandments, however, are listed out of order (10,

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Another way of explaining some of Blake’s irregularities arises from the tablets in “Job’s Evil Dream.” There the sixth, seventh, and eighth Commandments, according to the Hebrew reckoning, are listed in correct sequence, although they appear in the seventh, eighth, and ninth positions. In the sixth position is the phrase א-להך נתנ (“Your God has given”); (the dash is to be disregarded. Jewish law prohibits writing God’s name in this kind of context.) which we have discussed earlier from a formal standpoint. Although neither a Commandment nor an abbreviation for one, the phrase actually does originate in the sections of the Bible containing the Ten Commandments (Exodus, ch. 20 and Deuteronomy, ch. 5). In fact, these words are among the last in the fifth Commandment: “Honor your father and mother so that your days may be many upon the land which the Lord your God has given you.” One may be inclined to posit that Blake mistook the end of the fifth Commandment for the beginning of the sixth. This would not explain, though, how Blake managed to miscopy the final nūn (correctly written as ן, not נ), if he had a text in front of him.

begin page 182 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

However well they explain individual phenomena, neither of the hypotheses suggested so far—nor others like faulty memory, which give Blake the benefit of the doubt—explains everything. The unmethodical character of the irregularities leaves us with two possible explanations: willful subversion or ignorance. But the case for willful subversion—that Blake knew better but deliberately made errors to disparage the tradition he saw as “One [tyrannical] Law for the Lion and the Ox”; or that he chose to keep himself a greenhorn to Hebrew on principle—is simultaneously unsupportable and irrefutable. We do not know his mind. Nevertheless, we seem justified in one conclusion. Given their elementary nature, it makes most sense to see the begin page 183 | ↑ back to top irregularities as arising from ignorance. To see intention here is to argue that “jeopardi” spelled by an immigrant or elementary-school student is deliberate.

That mere carelessness is not Blake’s bane in the inscriptions can best be seen through his rendering of the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, א (‘alef). The letter requires a diagonal bar slanting up from right to left. In “The Laocoön” he slants the bar in the opposite direction, down from right to left. In the frontispiece to Job (1825), he slants it correctly. And in “Job’s Evil Dream” (also 1825), he does both. Since only an inch separates letters in the latter illumination, it is practically impossible to believe that he did not notice the discrepancy. In all probability, he thought that either form was acceptable—as in the Arabic numeral “four,” written “4” and “4.”

We can, at this point, formulate a judgment more specific than Harold Fisch’s when he says: Blake “knew little or no Hebrew.”15↤ 15 Harold Fisch, “William Blake,” The Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1971), IV, 1071-72. We have seen that he was not entirely without Hebrew. Even a brief note like the following found among the many proverb-like sayings in “The Laocoön” suggests some familiarity: “He repented that he had made Adam (of the Female, the Adamah).” A complete foreigner to Hebrew would not know that the “ah” ( ָה) ending is feminine. We have seen, nonetheless, that the first of Fisch’s possibilities—that Blake knew little Hebrew—best fits the evidence.16↤ 16 An assessment of Blake’s Hebrew does not require treatment of his every use of Hebrew. When taken as a whole, the instances not discussed in this paper (listed below) corroborate my findings. See “Figure Studies” in The Paintings of William Blake, ed. Darrell Figgis (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), p. 82; the title page and pl. 2 of Job, the last page of the third of the Night Thoughts, and pl. 35 of Milton, copy D.

One of the interesting unsolved problems connected with Blake’s Hebrew is his means of acquiring it. Unfortunately, even in an area like this, where no Hebrew writing is involved, the scholarship is problematic. Damon indicates the problem of Blake’s acquisition this way: “We do not know who Blake’s teachers were . . . [In] London . . . he continued his [Hebrew] studies, probably with some local rabbi . . . .”17↤ 17 Damon, p. 215. G. E. Bentley, Jr. seems to have found the solution. Basing his claim on the January 1803 letter to James, Bentley identifies William Hayley as Blake’s tutor.18↤ 18 Bentley, p. 526, n. 3. The letter, however, contains no reference to Hayley in this capacity. And a perusal of the Dictionary of National Biography and Hayley’s own Memoirs reveals no evidence that Hayley knew enough Hebrew to serve as tutor.19↤ 19 William Hayley, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of William Hayley, Esq., ed. John Johnson (London: Henry Colburn & Co., 1823). Even with some energetic digging and good fortune, it is possible, to use Blake’s words, that “this mystery never shall cease.”20↤ 20 William Blake, The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (London: Nonesuch Press, 1927), p. 94.