MINUTE PARTICULARS

BLAKE AND MORLAND: THE FIRST STATE OF “THE INDUSTRIOUS COTTAGER”

Among Blake’s more conventional efforts as a reproductive engraver are two companion prints, “The Idle Laundress” and “The Industrious Cottager,” both published by J. R. Smith

Although the newly discovered state (illus. 1) has been cropped closely along its lower margin, the signatures of the designer and engraver are preserved: Morland pinx (left), Blake sculp (right). The signature on the right cannot be seen in the photograph, but is clear in the original. In what Keynes calls the first state (illus. 2), dated 1788 in the imprint, and in the final state issued by H. Macklin3↤ 3 Very likely the successor (and son?) of Thomas Macklin, the engraver and print publisher who employed Balke to execute “Morning Amusement” and “Evening Amusement” after Watteau (1782), “The Fall of Rosamond” after Stothard (1783), and “Robin Hood and Clorinda” after Meheux (1783). in 1803, the signatures are Painted by G. Morland and Engraved by W. Blake. Of more begin page 259 | ↑ back to top importance are the differences in the designs. The newly discovered print is a fine, rich impression, whereas copies of the previously recorded 1788 state typically exhibit considerable wear. Note, for example, the hatching lines on the woman’s clothing over her breasts. Clearly, illus. 1 is the true first state.

The most significant changes between the first two states reproduced here are in the faces. In the first, the child’s uplifted eyes are particularly prominent. In the second, they have

Unfortunately Morland’s oil painting of the design has been lost,4↤ 4 The painting, 14 × 17 1/2 inches, was in the collection of H. Darrell Brown and exhibited at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1910. See Catalogue of a Collection of Pictures Including Examples of the Works of the Brothers Le Nain and Other Works of Art (London: Burlington Club, 1910), no. 22. The painting is said to be lost—see David Winter’s unpublished dissertation, George Morland (1763-1804) (Stanford University, 1977). and thus we are not able to determine without question which version is closer begin page 260 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

W. M. Rossetti wrote in the margin of his copy of Gilchrist’s Life of Blake that, except “for Linnell, Blake’s last years would have been employed . . . [in] making a set of Morland’s pig and ploughboy subjects.”5↤ 5 Quoted in G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 274. Rossetti notes that “it was, I think, [Alexander] Munro who told me this Nov. [18]63, as if he knew it from some authentic source.”6↤ 6 Bentley, Blake Records, p. 274, n. 1. This “source” may have known that Blake had indeed engraved one of Morland’s large pigs in “The Idle Laundress,” and projected Blake’s horrid fate on the basis of his commission of 1788. Yet Blake’s copying of Morland was not without redeeming value, at least in his own eyes. In one of his odder Notebook jottings, Blake quoted from a story from Bell’s Weekly of 4 August 1811, p. 248, concerning a jailed artist, Peter Le Cave, who had been Morland’s assistant. Le Cave claimed “that many Paintings of his were only Varnished over by Morland & sold by that Artist as his own.” On this point Blake commented that “It confirms the Suspition I entertained concerning those two [Prints del] I engraved From for J. R. Smith. That Morland could not have Painted them as they were the works of a Correct Mind & no Blurrer.”7↤ 7 The Notebook of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, Revised Edition (New York: Readex Books, 1977), p. N59 transcript. By dissociating “The Industrious Cottager” and “The Idle Laundress” from an artist of whom he disapproved, Blake was able to compliment these works and justify his own efforts in copying them.

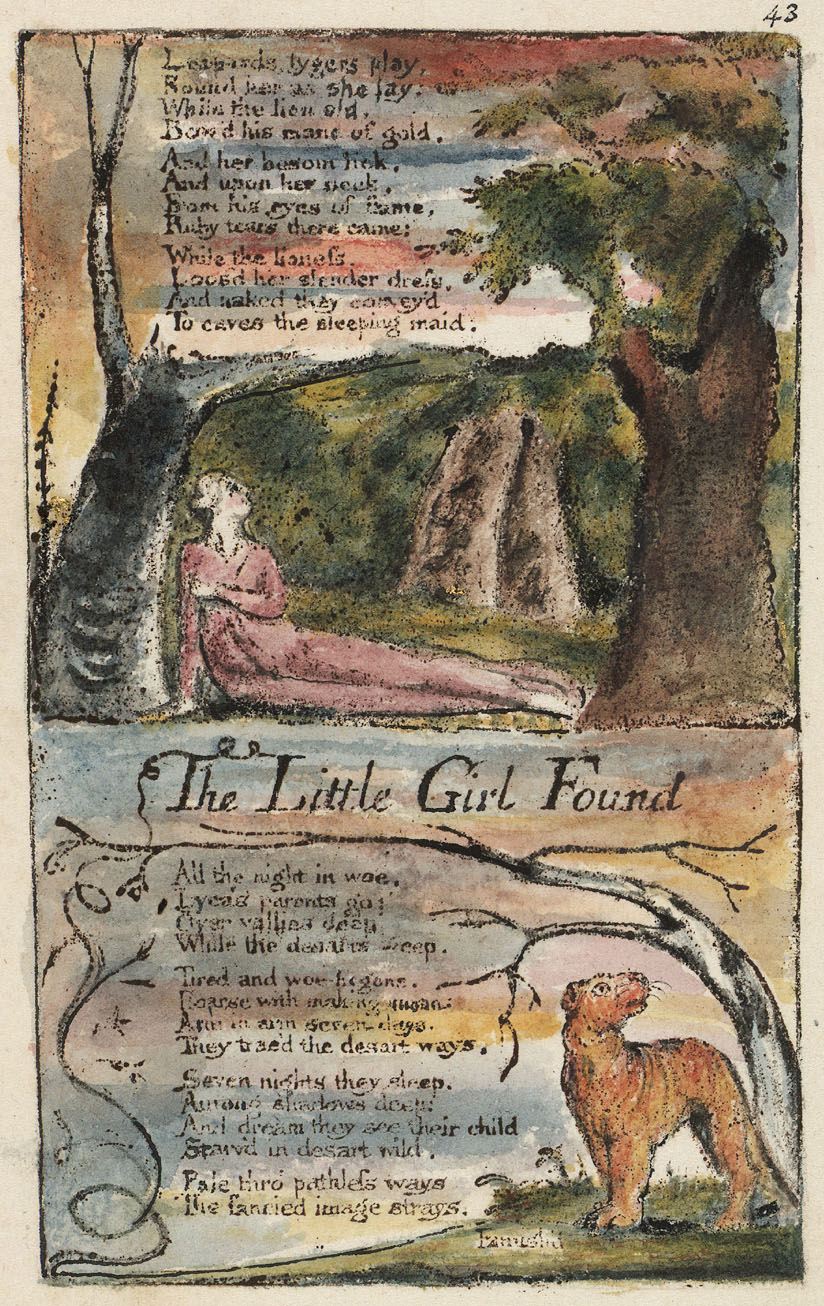

That Blake did indeed find something of worth in these two paintings is supported by his borrowings from them. The thick trunks of the two large trees behind the figures in “The Industrious Cottager” lean towards each other. Blake repeated this same configuration in the background of the upper design on the second plate of “The Little Girl Lost” in Songs of Experience (illus. 3) and behind Nebuchadnezzar on plate 24 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Apparently Blake found this motif to be a way of representing the dense and impenetrable nature of the forest of experience where children lose their way and beasts roam. To the right of the cottager’s left foot (clearer in illus. 2 than in 1) is a clump of spiky leaves. Many years later Blake engraved a remarkably similar plant in the lower margin of Job, plate 6 (illus. 4). Also in this corner of plate 6, just below the thistles, is one of Blake’s typically large leaves that appear in a number of his works (for example, Europe, plate 12). Leaves of this sort, growing close to the begin page 261 | ↑ back to top ground, also appear in the lower right area of “The Industrious Cottager.” These admittedly minor borrowings show once again Blake’s talent for making use of motifs he learned from works very unlike his own.