article

begin page 250 | ↑ back to topMR. JACKO “KNOWS WHAT RIDING IS” IN 1785: DATING BLAKE’S ISLAND IN THE MOON

Despite several determined attempts to fix the dates of William Blake’s writings, interest in the chronology of the poems continues, stimulated by the related concern to understand precisely Blake’s relationship to his age. In this context, An Island in the Moon excites special interest because of its many allusions to the contemporary scene and its importance as a central biographical document.1↤ 1 Attempts to link Blake’s Island with specific historical events and individuals include: Edwin J. Ellis and W. B. Yeats, ed., The Works of William Blake, Poetic, Symbolic and Critical (London, 1893), I, 201; John Sampson, ed., The Poetical Works of William Blake (London: Clarendon, 1905), p. 51; Edwin J. Ellis, ed., The Poetical Works of William Blake (London: Chatto and Windus, 1906), I, 154; S. Foster Damon, William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1924), pp. 29, 32-34, 264-66; Bernard Blackstone, English Blake (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1949), pp. 18-26; David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 3rd ed., rev. (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1977), pp. 91-114; Mona Wilson, The Life of William Blake, rev. ed. (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1948), pp. 353-54; Nancy Bogen, “William Blake’s ‘Island in the Moon’ Revisited,” Satire Newsletter, 5 (1968), 110-17; Stanley Gardner, Blake, Literature in Perspective (London: Evans Bros., 1968), pp. 61-66; Rodney M. Baine and Mary R. Baine, “Blake’s Inflammable Gass,” Blake Newsletter, 10 (Fall, 1976), 51-52. Breaking away from the undue emphasis upon Blake’s personal satire are Martha England, “The Satiric Blake: Apprenticeship in the Haymarket?” BNYPL, 73 (1969), 440-64, 531-50, and William Royce Campbell, “The Aesthetic Integrity of Blake’s Island in the Moon,” Blake Studies, 3 (Fall, 1970), 137-47. The scholarly consensus that Blake was writing An Island in 1784 is most forcefully represented by the arguments of David Erdman and G. E. Bentley, Jr.2↤ 2 Erdman, Prophet, pp. 91-96; G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon, 1977), pp. 221-23. Drawing upon the unpublished researches of Palmer Brown and Anne Buck,3↤ 3 See the Palmer Brown and Anne Buck correspondence in the Island file, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. I am indebted to Mr. P. Woudhuysen, Keeper, Department of Manuscripts and Printed Books, Fitzwilliam Museum, for directing me to these documents. these scholars argue that allusions to short-lived, contemporary fashions in ladies’ dress, together with other supporting evidence, narrow the date of the manuscript to late 1784. In this article I propose to go over the familiar ground mapped by Erdman and Bentley, and to argue that Blake was very probably composing An Island in 1785 or perhaps slightly later.4↤ 4 Among recent commentators on An Island I find only two voices dissenting from the 1784 date. Nancy Bogen, “‘Island’ Revisited,” p. 115, postulates a slightly later time of writing, “for if this work records actual events, chances are that it was written after the events occurred, not while they were in progress” (p. 117). Kathleen Raine, Blake and Tradition (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969), I, 17, 379, dates An Island after 1787 on the grounds that the draft of “The Little Boy Lost” in chapter 11 shows that Blake was influenced by Thomas Taylor’s translation of Plotinus’ Concerning the Beautiful (1787).

In chapter 8 of An Island Miss Gittipin quickly wearies of her companions’ bookish talk and turns to her “favourite topic,” the supposed distance between her own cloistered life and the freer social whirl of the Misses Double Elephant and Filligreework. “Im sure I never see any pleasure,” laments Miss Gittipin, ↤ 5 The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, with a commentary by Harold Bloom (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970), p. 447. All Blake quotations are from this edition.

theres Double Elephants Girls they have their own way, & theres Miss Filligree work she goes out in her coaches & her footman & her maids & Stormonts & Balloon hats & a pair of Gloves every day & the sorrows of Werter & Robinsons & the Queen of Frances Puss colour & my Cousin Gibble Gabble says that I am like nobody else I might as well be in a nunnery There they go in Post chaises & Stages to Vauxhall & Ranelagh And I hardly know what a coach is, except when I go to Mr Jacko’s he knows what riding is & his wife is the most agreeable woman you hardly know she has a tongue in her head5

Scholars agree that Blake was writing An Island during that relatively quiet period in his life between the printing of Poetical Sketches in 17836↤ 6 If the “Advertisement” to Poetical Sketches (Poetry and Prose, p. 764) does not exaggerate Blake’s devotion to his “profession” of engraving and his consequent neglect of poetry during 1778-83, then An Island must be later than 1783. Erdman, Prophet, pp. 92-93, dismisses the older view that An Island reflects Blake’s break with the “Mathew Circle” in 1784, but it is possible that the Mathews’ conversaziones were the occasion for, though not the specific targets of, Blake’s satire. J. T. Smith, Nollekens and His Times (London, 1829), II, 464, says that after 1783 “Blake’s visits” to the Mathews “were not so frequent,” which suggests that the break may have been gradual rather than sudden. and the etching of Songs of Innocence in 1789.7↤ 7 By 1789 Blake had revised, illustrated, and etched three songs found in An Island, chapter 11, as “Holy Thursday,” “The Little Boy Lost,” and “Nurse’s Song” of Songs of Innocence (title page dated 1789). But narrowing the date within this period depends in large part upon Miss Gittipin’s catalogue of “pleasures,” specifically “Balloon hats . . . the sorrows of Werter & Robinsons.”8↤ 8 Other objects envied by Miss Gittipin do not help to pinpoint the date of An Island. “Stormonts” were almost certainly items of dress associated with Louisa Cathcart, the second wife of David Murray, Seventh Viscount Stormont. Anne Buck (letter of 8 Aug. 1952 to L. A. Holder) found “Stormont gowns” mentioned in the Lady’s Magazine for March, 1781. I have found no reference to “Stormonts” during the period 1783-89. The “Queen of Frances Puss [i.e., puce] colour,” on the other hand, is found in the fashion columns throughout this period and is therefore irrelevant to the question of date. It may be of some interest to note that the coaches so envied by Miss Gittipin were the objects of heavy taxation during 1785. See the Daily Universal Register for 24 September 1785. “Balloon hats” so admired by Miss Gittipin were introduced into England from France in late 1783. In December 1783 the European Magazine’s “Man Milliner” regretted the inconvenience of the cumbersome style of hat though he had to admit that the “engaging actress, Miss Farren, [who] wore one of these whimsical hats this evening, in the character of Estifania . . . lost none of her beauty under it.”9↤ 9 Eur. Mag., 4 (Dec. 1783), 406. Elizabeth Farren played Estifania in Beaumont and Fletcher’s Rule a Wife and Have a Wife only once in 1783, with the Drury Lane company on 27 November.10↤ 10 The London Stage 1660-1800, Part 5, 1776-1800, ed. Charles B. Hogan (Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 1968), pp. 661, 673. From the play-house to the fashionable London salons appears to have been a short step, for the December Lady’s Magazine reported the balloon hat and “Robinson” hat (also admired by Miss Gittipin) under “FASHIONABLE DRESSES.”11↤ 11 Lady’s Mag., 14 (Dec. 1783), 650. When Vauxhall and Ranelagh—the famous begin page 251 | ↑ back to top pleasure gardens attended by Miss Filligreework—opened their doors on Easter Monday, 1784,12↤ 12 See E. Beresford Chancellor, The Pleasure Haunts of London (London: Constable, 1925), pp. 209, 233-35. Ranelagh, with its rotunda, was a year-round pleasure spot. Vauxhall normally opened on Easter Monday, but in 1785 it opened several weeks later, on 19 May. See Eur. Mag., 7 (May 1785), 356. the beau monde arrived in balloon hats and “Robinsons,” various items of dress associated with Mary “Perdita” Robinson.13↤ 13 Balloon hats were fashionable during the 1784 season. See Eur. Mag., 4 (Dec. 1783), 406, Gazetteer for 31 Jan., 9 Feb., 19 Feb., 11 June 1784, and Morning Herald, and Daily Advertiser, 18 Sept. 1784, for a sample of the accounts of this fashion. “Robinson” gowns, hats, and other apparel were fashionable from the early 1780’s. See Lady’s Mag., 14 (March 1783), 121; (April, 1783), 187; (May 1783), 268; (Dec. 1783), 650; 15 (March 1784), 154; (June 1784), 303. These fashions flourished through the summer season and into the autumn of 1784, when the chill winds forced the closing of Vauxhall.

Like “Robinsons,” Miss Filligreework’s “sorrows of Werter” probably included a fairly large number of stylish hats and dresses inspired by Goethe’s popular book during the 1780’s, but if so these fashions have not been traced. The earliest known reference to such a style appeared after the close of Vauxhall in the Gazetteer of 9 December 1784. There the “Werter bonnet” is reported to be “much the rage.”14↤ 14 “Werter” bonnets were reported in the Gazetteer for 16 Dec. 1784 and 13 Jan. 1785 (first noticed by Palmer Brown).

But the real question for the date of An Island is whether balloon hats, Robinsons, and Werters survived the winter months of 1784-85 and were to be seen when the pleasure gardens opened in the spring of 1785. On 26 July 1785 the Gazetteer announced: “The balloon hat has had its day;—the Werter, Lunardi, and Gypsey are now on the decline, while the umbrella bonnet is making rapid advances.” This statement, together with the absence of other references to these fashions in 1785, and the disappearance of Perdita Robinson from the fashionable scene after 1784,15↤ 15 The precise date of Perdita’s illness and subsequent departure for the spas of Europe is in dispute. For a sentimentalized account, see Memoirs of the Late Mrs. Robinson (London, 1803), II, 95-98. The Gazetteer, 28 Dec. 1784, includes the rumor that “Perdita is returned from Paris” while the same newspaper for 18 Jan. 1785 announced her fall from fashion. have been taken to mean that balloon hats, Robinsons, and Werters were old hat by the beginning of 1785. From my reading of the fashion columns of these years, however, I rather suspect that a journalist writing late in July—very late in the London “season”—would be unlikely to write an obituary on a style six months dead. More probably, balloon hats had by late July been replaced fairly recently, while Werter bonnets were, as he says, “on the decline” but still visible. That Blake could have seen, heard of, or read about these fashions in 1785 and used them in An Island seems to be very probable.

That Blake was writing An Island in 1785 or slightly later gains support when one considers Miss Gittipin’s friend Mr. Jacko who “knows what riding is.” Jacko, according to David Erdman, is Blake’s caricature of Richard Cosway, the “mushroom-rich miniature painter and . . . fabulous dandy” known for his simian features.16↤ 16 Erdman, Prophet, p. 96. Erdman notes that Cosway was called “little Jack-a-dang” but he does not say when. J. T. Smith, Nollekens, II, 407, claimed that the following undated lines attributed to Peter Pindar were attached to Cosway’s door, which was guarded by two stone lions: When a man to a fair for a show brings a lion, ’Tis usual a monkey the sign-post to tie on: But here the old custom reversed is seen, For the lion’s without—and the monkey’s within. Erdman traces the name “Jacko” to “General Jacko,” identified by M. D. George in the Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum as “an astonishing monkey from the fair of St. Germain’s, Paris, who performed at Astley’s Amphitheatre during the summer of 1784.”17↤ 17 Mary Dorothy George, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, VI, 1784-1792 (London: B. M. Trustees, 1938), no. 6715. Since Astley’s was primarily an equestrian circus, the link between General Jacko and Blake’s Mr. Jacko who “knows what riding is” seems plausible enough. And, of course, General Jacko’s appearance in 1784 is consistent with the date of An Island established by Erdman on other grounds.

M. D. George, however, appears to be a year off in dating the French ape’s English engagement.18↤ 18 Evidently M. D. George merely slipped in transcribing the handwritten date beside the 4 April 1785 Gazetteer clipping in the Banks Collection of the British Library, vol. I, fol. 77v. A search of the newspapers for 1784 reveals no reference to General Jacko. The Gazetteer, which regularly carried advertisements for Philip Astley’s Westminster-Bridge circus, makes no mention of Jacko among the many performers of the 1784 season (21 April-14 October). But in April 1785 both the Gazetteer and the Daily Universal Register (later The Times) announced Jacko’s exhibition in language that unmistakably identifies the monkey as a new arrival on the London theatrical scene.19↤ 19 See Daily Univ. Reg., 5 April 1785. The Fair of St. Germain, Paris, where Astley acquired General Jacko, usually closed by Palm Sunday, according to Leo Hughes, A Century of English Farce (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1956), p. 107. Jacko did not appear in England until the second week after Easter 1785. The Gazetteer for 4 April 1785 proclaimed:

The Second Week’s Exhibition will Continue until Saturday, the 9th of April [and will include] General Jacko, (never exhibited in England) from the Fair of St. Germain’s, Paris, who has been celebrated for his astonishing Performances on the TIGHTROPE, and other Exercises, which are beyond Conception.Throughout the summer of 1785 General Jacko was one of Astley’s featured entertainers. By September Jacko was dividing his talents between Astley’s and the rival Sadler’s Wells and Royal Circus where, dressed in red, he rode a horse called Marplot.20↤ 20 Daily Univ. Reg. for 23, 26, 27 Sept. 1785. Although Jacko’s manifest appeal for English audiences in 1785 suggests that he probably performed somewhere in London in the following year, evidently Astley did not renew Jacko’s contract when the Amphitheatre re-opened Easter Monday, 17 April 1786.21↤ 21 “Jacko” and the Learned Pig figure prominently in Gillray’s print, “The Theatrical War” (30 June 1787).

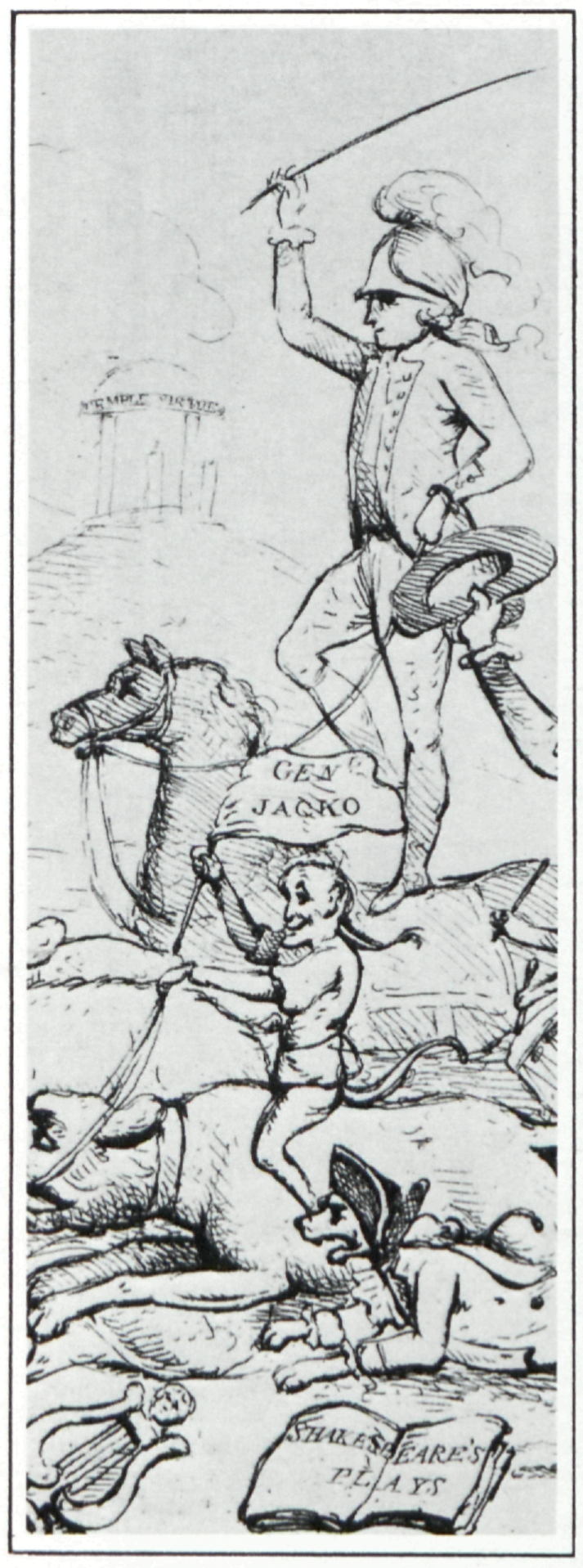

The question of course is what to do with this monkey business. At the least we may re-date c. 1785 the satirical engraving, “The Downfall of Taste & Genius or The World as it goes” (illus. 1), attributed to Blake’s fellow artist and engraver Samuel Collings and dated c. 1784 by M. D. George.22↤ 22 B. M. Satires, no. 6715. Blake engraved four prints after Collings for The Wit’s Magazine (Jan.-May 1784). See Bentley, Blake Books, pp. 634-35. Dr. E. W. Pitcher points out that the subtitle of Collings’ print probably echoes Voltaire’s satire on Parisian customs, “Babouc, or the World as it Goes.” See Robert D. Mayo, The English Novel in the Magazines 1740-1815 (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern Univ. Press, 1962), item 132. The print depicts the rout of true native arts by a combined force of imported and domestic entertainers. General Jacko rides a mastiff and carries an identifying pennant inscribed “Genl Jacko.” The Learned Pig (a domestic porker whose erudition Samuel Johnson wittily discussed before his death)23↤ 23 Samuel Johnson, Nov. 1784, as quoted in James Boswell, Boswell’s Life of Johnson, ed. George Birkbeck Hill and L. F. Powell, IV (Oxford: Clarendon, 1934), 373-74, 547-48, where Johnson argues that education, however painful, has at least prolonged the learned pig’s life. When Anna Seward reported the appearance of the pig, it was performing in Nottingham and apparently did not reach London until the spring of 1785. leads the pack of trained animals which includes a troupe of dancing dogs—such as Astley and other impressarios imported from France and Italy during the 1780’s—and a rabbit beating a drum, probably to be identified with the “Wonderful Hare” that performed on the same bill with dancing dogs, the Learned Pig, and General Jacko at Sadler’s Wells in September 1785.24↤ 24 Daily Univ. Reg., 26 Sept. 1785. The ringmaster atop a prancing pony may be a caricature of Philip or John Astley or of Charles Hughes, Astley’s counterpart at the Royal Circus. Above the inverted “triumph” of Dulness over light in a French balloon sails Vincenzo Lunardi as the presiding spirit of the whole.25↤ 25 Lunardi’s first balloon flight on 15 Sept. 1784 was followed by several others in the following year. The European Magazine, 7 (May 1785), 385, reported that on 13 May 1785 Lunardi ascended in a balloon painted like the “Union Flag of England.” In Collings’ print, however, Lunardi’s balloon is identifiably French. All of these characters and creatures were performing in London during 1785, and it is almost certain that Collings engraved “The Downfall of Taste & Genius” in that year as a comment on the contemporary state of the arts.26↤ 26 See B. M. Satires, no. 6715, for M. D. George’s fine description of the details of the print. It is clear that Jacko is a caricature of a real person, though I have not identified the target of the joke.

The relevance of the revised date of General Jacko’s English engagement to the date of Blake’s Island in the Moon is less clear cut. Scholars convinced on other grounds that the evidence of composition overwhelmingly points to 1784 have some reason to disregard the Mr. Jacko/General Jacko connection as accidental without severing the Mr. Jacko/Richard Cosway identification urged by Erdman. In the first place, Blake’s Mr. Jacko “knows what riding is” in a coach, but nowhere in An Island is begin page 252-253 | ↑ back to top

begin page 254 | ↑ back to top he said to ride a horse. Further, the name “Jacko” may have been, like “Jocko” following Buffon’s coinage of 1766,27↤ 27 Buffon, Natural History, General and Particular, trans. William Smellie, 2nd ed. (London, 1785), VIII, 77-105. See also OED entry “Jocko.” Buffon, pp. 77-78, says of jockos and orangutangs: “of all the apes, they have the greatest resemblance to man.” a fairly common name for a monkey in the late eighteenth century. For example, the Morning Herald, and Daily Advertiser for 2 December 1784 included a poem in the manner of Gray’s mock-elegiac Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat called “Stanzas on the Death of a Lady’s much esteemed Monkey” which contains the lines:For Death, the parent of all dread,There exists, moreover, a long tradition of English combinations of “Jack” and “ape” that might have inspired Blake to construct a comic name for Miss Gittipin’s friend like those given to other islanders. And, finally, if the claim in the newspapers of 1785 is not merely advertising puffery, then General Jacko had been “celebrated for these Two Years last past”28↤ 28 Daily Univ. Reg., 26 April 1785. and Blake could have heard of the French ape before his English tour of 1785.

Nor man nor monkey can controul;

So Jackoe finds it—now he’s dead—

Old maids, have mercy on his soul!

There are, then, several plausible explanations for Blake’s use of the name Jacko, but none, I would urge, more probable than Blake’s awareness of General Jacko’s much publicized equestrian act of 1785. Nor does the other evidence usually taken to date An Island 1784 contradict this later date. The explicit reference to the Royal Academy Exhibition, the possible allusion to the Handel Festival of 1784, and the identification of Quid the Cynic’s plan for “Illuminating the Manuscript” (ch. 11) all admit of differing interpretations and cannot be decisive as to date.

In chapter 7 Suction the Epicurean, who may be smarting from a recent disappointment, says “If I dont knock them all up next year in the Exhibition Ill be hangd.” From the context it is clear that Suction looks forward to the annual Royal Academy Exhibition in May. Though Suction has never been identified as Blake, the fact that Blake contributed paintings to the Royal Academy exhibits in 1780, 1784, 1785, and not again until 1799 has been taken as evidence that Suction is speaking sometime in May-December 1784 of the 1785 exhibition the following year.29↤ 29 For example, Erdman, Prophet, p. 91 fn. 5, and Bentley, Blake Books, p. 222 fn. 3. But this is to confuse a fictional character’s hypothetical ambition with the author’s actual performance. In any event we do not know that Blake did not intend to exhibit in 1786.

The possible allusion to the 1784 Handel Festival in An Island, chapter 11, identified by David Erdman30↤ 30 Erdman, Prophet, p. 102. I find even less convincing than the explicit Royal Academy reference. The popularity of, and patriotic objections to, overpaid foreign musicians (and trained animals for that matter)31↤ 31 An anonymous writer in the Daily Univ. Reg., 6 April 1785, complained that the “revenues of a learned horse, or a learned dog, or a learned pig, would preserve from indigence half a dozen learned men.” reflected in Blake’s Doctor Clash and Signior Falalasole are familiar subjects of eighteenth-century satire. But, even granting that the mention of “handels waterpiece” might suggest a Handel Festival, such festivals were held in Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon not only in 1784, but also in 1785, 1786, and 1787.32↤ 32 See Charles Burney, An Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster-Abbey, and the Pantheon, May 26, 27, 29, June 3, 5, 1784 (London, 1785), and European Mag., 8 (July 1785), 78; 9 (June 1786), 468; 10 (June 1787), 459.

The identification of Quid’s proposal on the final page of text for “Illuminating the Manuscript” with George Cumberland’s plan to produce engraved mirror writing is similarly inconclusive. Once taken to be an allusion to Blake’s own method of illuminated printing, Quid’s ambitious plan is identified by Erdman and Bentley with Cumberland’s because Cumberland, like Quid, proposed to print “2000” copies of any work by his method.33↤ 33 Damon, Philosophy and Symbols, pp. 32-33, identified Quid’s plan as Blake’s own. For the Quid-Cumberland link, see Erdman, Prophet, p. 100, and Bentley, Blake Books, p. 222. For Blake’s early friendship with Cumberland, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969), pp. 17, 362. Cumberland’s letter to his brother of early 1784 in which he proposes to print 2,000 copies of his engraved writing is B. M. Add. MS. 36494, fol. 232, transcribed by Geoffrey Keynes, Blake Studies: Essays on His Life and Work, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1971), pp. 231-32. But Quid’s proposal is not sufficiently detailed to be confidently equated with either Blake’s or Cumberland’s. The published reports in late 1784 of Cumberland’s “New Mode of Printing”34↤ 34 Cumberland published a description of his “New Mode of Printing” in Henry Maty’s A New Review; with Literary Curiosities, and Literary Intelligence, 6 (Oct. 1784), 318-19. Although Erdman, Prophet, p. 100 fn. 22, says it is “hard to think who” Cumberland might be in An Island, it would seem logical to identify Cumberland with Quid on the evidence Erdman presents. One might argue that Quid, like Cumberland and unlike Blake with whom he is almost always identified, does not seem to be a professional engraver or printer. Quid says that he “would have all the writing Engraved instead of Printed” and that “they would Print off two thousand” copies. One could see George “Candid” Cumberland, a mere amateur engraver and printer, farming out the production of these volumes. do not include the number of potential copies, and to assume that Cumberland told Blake privately of his plan may be to pile conjecture upon conjecture without hope of discovering the facts of the case.

Although these allusions do not help us to pinpoint the year in which Blake composed An Island, some of them may help to indicate the season in which the action of the satire is supposed to occur. In addition to the annual spring celebration by the charity school children of “Holy Thursday,”35↤ 35 The annual charity school service described in the draft of “Holy Thursday” (ch. 11) was first held in St. Paul’s Cathedral on 2 May 1782, and annually thereafter (e.g., 12 June 1783, 10 June 1784, 26 May 1785, 1 June 1786, 7 June 1787, 5 June 1788, 28 May 1789) until late in the nineteenth century. For the distinction between these services and the “Holy Thursdays” of the church calendar see W. H. Stevenson, ed., The Poems of William Blake, text ed. by David V. Erdman, Longman Annotated English Poets (London: Longman, 1971), p. 60 fn., and Thomas E. Connolly, “The Real ‘Holy Thursday’ of William Blake,” Blake Studies, 6 (1975), 179-87. the annual Royal Academy exhibitions in May,36↤ 36 As Erdman observes (Prophet, p. 91 fn.), Suction’s reference to “next year” would be most appropriate from May to December, though I have heard “academics” of a different sort refer to next year, i.e., the Sept. school opening, in July. the spring music festivals, and the “high fashion” season of Vauxhall and Ranelagh, there is Steelyard the Lawgiver’s song, “As I walkd forth one may morning” (ch. 9), and a reference to cricket in chapter 11, a game played during the warm spring and summer months. The Antiquarian’s swallows that “seemd to be going on their passage” (ch. 1)37↤ 37 Even this passing reference to swallows may reflect Blake’s awareness of the contemporary dispute over the migration and hibernation theories to which John Hunter and Samuel Johnson (both mentioned in An Island) contributed. See Jean Dorst, The Migration of Birds, trans. C. D. Sherman (London: Heineman, 1962), pp. 3, 8-9. “Pliny,” cited by Blake’s Antiquarian, was usually cited by the hibernationists. suggests either an autumn or a spring migration, while, on the other side, the song in chapter 11 celebrating the victory of William the Prince of Orange in November 1688 would, I suppose, be most appropriate to one of the yearly celebrations of that event in November.

In sum, Blake was probably composing An Island in the Moon during the spring (or perhaps the autumn) of 1785 when General Jacko was performing for London audiences his exercises “beyond Conception” and the styles of dress envied by Miss Gittipin were still fresh in the public mind. Yet it is difficult to claim that 1785 is more than a probable terminus a quo for the unique manuscript in the Fitzwilliam Museum. David Erdman observes, perhaps too confidently, that the manuscript was “obviously copied from an earlier draft, the most frequent revision being a second thought replacing a word just written down.”38↤ 38 Erdman, Poetry and Prose, p. 766. G. E. Bentley, Jr. concludes from the evidence of changes in handwriting, inks, and pen-points that there were “seven stages of work”39↤ 39 Bentley, Blake Booke, p. 223. on the text. Though I have not seen positive evidence that An Island is later than 1785, if these scholars are right, then it is not impossible that Blake was writing this manuscript slightly later than the events alluded to, perhaps over a period of time.

The evidence of fashions and trained animals, then, does not provide as conclusive a date for An Island as one would wish to have, though it does redefine the limits of our uncertainty. One happy side effect of knowing about learned pigs and wonderful hares may be of interest to readers of Blake. I for one now have a clearer sense of Blake’s meaning in the bitter and ironic directive found on page 40 of The Notebook:

Give pensions to the Learned PigBut this may be to start more hares than I am able to run down.

Or the Hare playing on a Tabor

begin page 255 | ↑ back to top Anglus can never see Perfection

But in the Journeymans Labour[.]