review

Kay Parkhurst Easson and Roger R. Easson, eds. Milton: A Poem by William Blake. The Sacred Art of the World Series. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala in association with Random House of New York, 1978. 178 pp., illus. $17.95, cloth; $9.95, paper.

Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr.

The enterprising Eassons—founders of both Blake Studies and the American Blake Foundation, presumably with the advice and consent of their Foundation, certainly with its imprimatur—are now initiating a series of color facsimilies of Blake’s illuminated books. The conception behind this series is commendable; the execution is problematic, yet emendable. Copy B (the Huntington Library copy) of Milton, never before issued in facsimile, has now been published: richer in coloration than Copy A (in the British Library) but identical in all essential points to it, except for its border design on plate 30, Copy B offers the best, because most finished, conception of Blake’s initial idea for this prophecy. Copy C of the poem, unfortunately, is still unavailable in facsimile, a fact that is particularly regrettable inasmuch as this copy, in the New York Public Library, is crucially transitional. One thing is certain: a color-facsimile, even with imperfect coloration, is superior to the black and white reproductions now readliy available for classroom use. The Easson edition has the futher features of a separate text for the poem, accompanied by a commentary and brief bibliography, the commentary focusing attention upon Milton’s journey, its geography, and what, ingenuously, the Eassons call “the structure of prophecy.”

One would like to say that the separate text, commentary, and recommended readings constitute additional advantages—are icing on the cake. But they are not, for this is a cake from which many will wish to pull away the icing. It is not very good, really, and one can only hope that the recipe for making it will soon be improved. Start with the text, which normalizes punctuation “for reading convenience,” spelling where it “interferes with current reading habits,” and capitalization “only when change in, or addition of, a mark of punctuation necessitated such alteration” (p. 59; my italics). And take the matter of capitalization first. The editors’ explanation covers the four shifts to lower casing, as well as one to upper, in 5:1-5—but none of these others: “for” to “For” (3:22), “blessed” to “Blessed” (3 [CopyD]:4), “Island” to “island” (4:20), “Dead” to “dead” (4:29), “Two” to “two” (5 [Copy D]:14), “Rocks” to “rocks” (5 [CopyD]:42), “but” to “But” (5:31). (N.B. I have checked only pp. 61-71 of this text, up to the beginning of plate 6). Normalization of spelling poses few problems here: “contemptible” for “contempable” on plate 2, or “cruelties” for “crueties” (5 [CopyD]:12), or “Persuaded” for “Perswaded” (5:38). However, there is a real question about whether to render a word like “pondring” poetically (“pond’ring”), or, as the Eassons do, prosaically (“pondering”; 3:17). And there is a notable error: “Finchely” for “Finchley” (4:5).

Punctuation is another matter altogether, complicated, admittedly, by the habits of another age, by possible eccentricities of Blake (perhaps we should now investigate the former—as Jerome McGann is doing for Byron—so as to come to some begin page 50 | ↑ back to top determination about the latter), plus the obvious difficulties of a printing medium that prevents absolute certainty about periods, commas, etc.—at least some of the time. In this regard, the Eassons’ editorial procedures are arbitrary—actually more Victorian than modern. At times, it is true, the insertion of a comma clarifies the meaning of words or phrases in the line, but correspondingly the alteration of end punctuation sometimes affects the sense of the entire line: in the first quatrain of the opening lyric, for instance, a question mark substitutes for one of exclamation; in the third quatrain of the same lyric, semi-colons replace colons in lines 1 and 2, and in line 3 a colon is replaced by an exclamation point. It is not clear in plate 3, line 16, why a hyphen is substituted for a comma, not even when current standards of punctuation are invoked; nor four lines later, why a hyphen substitutes for a colon. Especially annoying is the tendency to insert unauthorized exclamations whenever the editors’ collective temperature rises (e.g., 3:25; 3 [Copy D]:5; 4 [Copy D]:20, 26, 28; 5:18, 27, 28, 30, 50). Oddly, in plate 5, line 18 where an exclamation is sanctioned at mid-line, it is omitted in favor of a dull semi-colon: hence, “Mark well my words;” instead of “Mark well my words!”. Let the Bard witness. Let the Bard himself exclaim! The editors offer wise counsel: “the punctuation often shapes the reader’s perception of the meaning of Blake’s words” (p. 59). So wise is that counsel that these editors, henceforth, should follow it. And they should take into account a further matter: Blake’s punctuation is highly, provocatively rhetorical—often it is like an accent mark, a form of italics.

Everyone should be grateful to the Eassons for their wish, now fulfilling itself, to make previously unavailable copies of the illuminated books available—in color no less! At the same time, one might wish for a text faithful to the copy being reproduced and, in the future, hope that in place of the current critical apparatus there will be one more generously informative and more genuinely descriptive, one that lays stress on the visual component of these illuminated books.

In a textual note, we learn (I gather from second-hand authority rather than fresh investigation) that Copies A, B, and C all are “on paper watermarked 1808” (p. 59). We do not learn what is unique to Copy B, that two of its plates appear to carry an 1801 watermark (plate 23: “TMAN / [18]01” and plate 24: “WH / 1[801]”. Or on a list of recommended readings, inexplicably, we do not find reference to the searching commentaries by Leslie Brisman in Milton’s Poetry of Choice (1973) or by Christine Gallant in Blake and the Assimilation of Chaos (1978), nor any mention of three particularly important essays: Northrop Frye’s “Notes for a Commentary on Milton” (1957), Albert Cook’s “Blake’s Milton” (1972), and John Grant’s “The Female Awakening at the End of Blake’s Milton” (1976). It would be more than useful—it would seem essential—to be sent from this edition to other facsimiles of Milton: the Muir facsimile of Copy A and the Keynes-Trianon facsimile of Copy D, neither of which receives notice in the “bibliography.” And what of the elaborate notes on these illuminations provided by David Erdman in The Illuminated Blake? Surely they deserve mention here.

They receive none. Which points to the chief problem with the commentary the Eassons offer: it is a rather breezy encounter with the verbal text, and no encounter at all with the visual component of this illuminated book. That commentary, too, is inordinately preachy: “the reader must enter Milton loving Blake . . . If we fail to enter Milton lovingly we could become judgmental; we could attempt to assert control over Blake’s text. Then we would be the tyrant readers Blake would deplore” (pp. 139-40). The most satisfying portion of this commentary is that which charts Blake’s geography: “the eternal spaces of Eden, Beulah, and Golgonooza; the created spaces of Allamanda, Bowlahoola, and Golgonooza; and the illusory spaces of Entuthon Benython, Udan-Adan, and Ulro” (p. 145), and thereupon the effort to interiorize that geography, elucidating all by “definitions of the anatomy and physiology of the eye . . . drawn from the Rees Cyclopaedia” (p. 147), but not, surprisingly, by reference to Newton’s Opticks. The least satisfactory section of the commentary, on the other hand, is the one devoted to “the structure of prophecy” (pp. 158-70), hence the structure of Milton, which we are told correctly is a prophecy. Milton, according to this structural analysis, possesses four structures:

The first of these is the two-book structure . . . ; the second is a three-part thematic structure; the third is a structure of six aggregate journeys; fourth is a linear structure that underlies the poem and its events. (p. 160)However, we learn very little about the structural principles that everywhere inform Blake’s prophetic art—nowhere are engaged with such particularities as W. J. T. Mitchell, in Blake’s Composite Art, provides for the understanding of such art. Structure in Blake, says Mitchell, is “some species of ‘antiform’ . . . is a denial of our usual ideas of structure” (p. 165); “when we say . . . a structure of antiform, we mean that it treats as an illusion or fiction the temporal continuum which normally stands behind narrative, and that it is designed to subvert our assumption that the logical is equivalent to the chronological . . . Antiform means that the poem’s structure undercuts the whole notion of predictable linear chronology by embodying it as chaos” (pp. 169-70); “an essential feature of . . . [such a] structure . . . [is that] it repeats itself constantly, but is never quite the same” (p. 173); chapter and book do not depict “a temporal progression but . . . clarifications of particular kinds of error” (p. 185); each part contains “a sense of the whole, implying and alluding to all the others but reviewing the whole in terms of a distinct emphasis” (p. 192). Mitchell, of course, is talking about Jerusalem, but his remarks, especially these, pertain to Milton as well. And as we pursue Blakean structures, it is worth remembering with begin page 51 | ↑ back to top Fredric Jameson, in Marxism and Form, that “the surface of the work is a kind of mystification in its structure” (p. 413):

. . . the various elements of the work are ordered at various levels from the surface, and serve so to speak as pretexts each for the existence of a deeper one, so that in the long run everything in the work exists in order to bring to expression that deepest level of the work . . . or . . . to foreground the work’s most essential content.

(p. 409)

It is the “essential content” of Milton that never clearly surfaces in the Eassons’ commentary, never becomes foreground. And this is but an aspect of all my other complaints about this valuable, yet limited, edition: essential facts are missing, essential questions are never broached. What ought to be a question-answering commentary is a question-begging one. What is here in the way of explanation leaves us in the forest: “To redeem John Milton’s dualism, Blake . . . structured Milton in two books, with Book I being the male journey and Book II, the female journey. Since the feminine virtues . . . are ‘the weak,’ Book II is shorter, ‘weaker’ than Book I” (p. 161). Here and elsewhere, the forest we are in is a place of confusion and error: “John Milton, Blake thought, had seen people as being like sheep, appointed to their respective sheepfolds by the shepherd. Blake’s view, in clear contrast, is individual; judgment of the individual’s merits is the individual’s own responsibility” (p. 165). William Blake read Milton, if not De Doctrina Christiana, certainly Book III of Paradise Lost where Milton denies Calvin’s view of election. It is nice to be told of Blake that “he loves Milton” (p. 169)—and would be nicer still to be told that he was a great knower, understander of Milton. His perceptions of Milton have always been controversial; never, though, were they crude—nor so obviously mistaken.

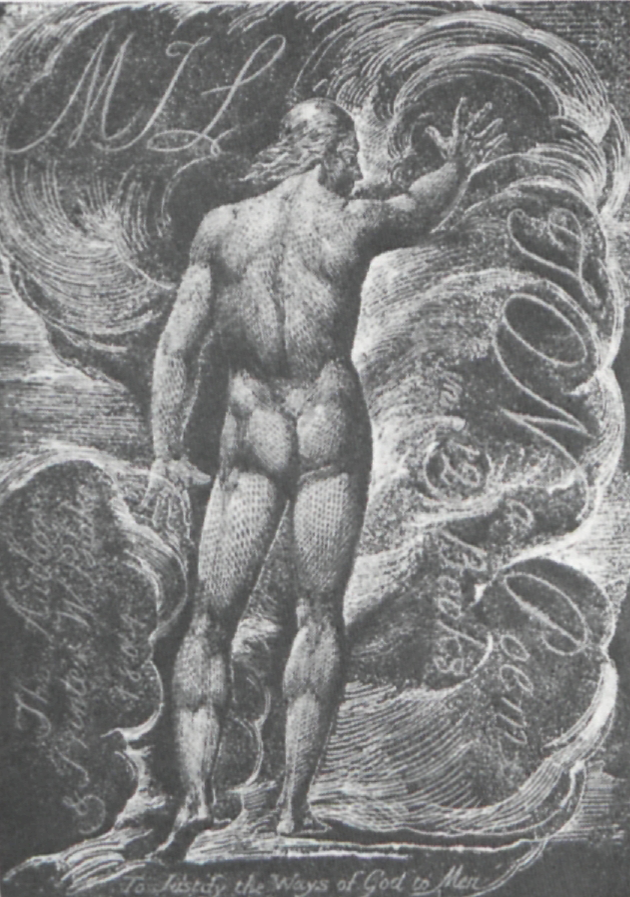

Morton D. Paley

A comparison of the Shambhala Milton reproduction with the original in the Henry E. Huntington Library shows that the color plates are of fair quality and free from gross distortions. There is, however, a tendency for the color register to be more intense in the reproduction than in Blake’s original; this, coupled with the choice of a glossy paper which is entirely unlike Blake’s, makes the Shambhala edition considerably less faithful to the original than it might have been. A few remarks on particular plates will bring out the consequences of these general differences. Plate numbers refer to the pagination of the Huntington copy, which is also that of the Shambhala edition.

Pl. 2. Blake’s yellow at r. becomes gold.

Pl. 3. Blake’s blues are much lighter than this.

Pl. 4. Blake’s blues are very much lighter, while the large white area behind Blake’s text becomes light blue.

Plate 6. Blake’s delicate color washes become blatant. There is much more yellow in the original than in the reproduction.

Plate 8. The two male bodies should have a rosier tinge; the flames should have less yellow and more blue in them. Blake’s background is not uniformly black as in this reproduction, but is variegated in tone.

Plate 11. Again Blake’s yellow turns to gold, and in general Blake’s colors are paler than this.

Plate 13. The body of Milton simply does not have the glaring whites reproduced. The background should be far more variegated.

Plate 15. Well reproduced on the whole, but the hill should be greener.

Plate 16. All areas behind text have been made some shade of blue, rather than white as they ought to be.

Plate 19. Blues too dark, gold instead of yellow.

Plate 20. There is more violet in the original.

Plate 23. Blake’s delicate rainbow wash has darkened.

Plate 24. The white area behind the text is blue again.

Plate 27. Blues too dark, yellows golden, whites not white enough.

Plate 28. The violet areas of the original have been lost entirely.

Plate 29. Fairly good, but the areas above and below William’s outstretched arm should be blue, not black.

Plate 32. The Luvah disc should be gray, not blue as here; the Urizen disc should be much lighter.

Plate 33. Robert’s body has been given a purplish tinge it ought not to have. The rich variations of dark blue in the background have been reduced to blackish opacity.

Plate 35. Very good reproduction of color washes.

Plate 36. The greens are too brownish, especially on Blake’s front lawn.

Plate 38. The color tones of the whole plate should be lighter.

Plate 40. The wash is much too violet, and many whites are altogether lost.

Plate 41. Color tones are generally too dark; the bluishness of the sky is lost.

It is of course understandable that a moderately priced reproduction cannot achieve the standard of fidelity that we expect of the much more expensive Trianon Press facsimiles. It is harder to understand why the Shambhala edition could not approach the fair reproductive quality of the Oxford University Press Marriage of Heaven and Hell, priced at $7.95. This book not only reproduces Blake’s colors with reasonable fidelity but also uses a paper similar in aesthetic effect to that used by Blake. Blake characteristically printed his illuminated works on cream-colored wove paper of medium weight, relatively smooth but not shiny. To print the plates of Milton on glossy paper is to radically alter the appearance of the original—and for no discernible reason. The late Ruthven Todd once wrote in a letter that he had had a terrible nightmare about Blake. In his dream Blake had been born in the Victorian period and had printed his illuminated works by chromo-lithography! The Shambhala Milton is not a fulfillment of that bad dream, but in some of its effects comes close to it.