article

begin page 148 | ↑ back to topA SUGGESTED REDATING OF A BLAKE LETTER TO THOMAS BUTTS

Blake’s letter to Thomas Butts presently dated 10 January 1802 should probably be dated 10 January 1803. Arguments for the redating are almost entirely internal, though they may gain some external authority from the reminder that it is not at all uncommon for people less afflicted by Spiritual Enemies and more involved with workaday time than Blake was to omit changing their mental calendars the first week or so into the new year.1↤ 1 The manuscript at Westminster Public Library establishes the fact that Blake dated his letter 1802. Unfortunately, the Chichester postmark was not stamped evenly or firmly enough for its date to be imprinted on the outside of the letter. The internal evidence is largely embodied in the correspondences italicized in the 10 January letter to Butts and the 30 January 1803 letter to James Blake from which I have excerpted the numbered passages placed in parallel columns listed below.2↤ 2 The page numbers following the excerpts refer to William Blake’s Writings, ed. G. E. Bentley, Jr. (Oxford Univ. Press, 1978). I use the punctuation and capitalization of this text as well, omitting, however, the half brackets and italicized letters used to indicate editorial emendation, I retain the ms. semicolon before “calld” in the first excerpt with certain misgivings about its authenticity. With the exception of the ambiguous and unrepresentative mss. for the 18 Jan. 1808 letter to Ozias Humphry, the 250 pages (and thirty-seven years worth) of Blake letters record only six other semicolons in extant mss. Two of these (22 Jun. 1804, 4 Aug. 1824) appear in quotations, another (14 Jul. 1826) in a formal receipt. The fact that the other three (27 Jul. 1804 [2], 31 Jan. 1826) appear in letters in which Blake complains of a “cold” is a curious coincidence, if not (alas) the kind of internal evidence one can adduce to bring the “illness” of 10 Jan. a year closer to the “Cold” reference of 30 January than the received dating now allows. Conceivably the interruptive irrelevance of the 1826 and 10 Jan. semicolons could suggest that even the thought of a cold helped induce the misstrokes or splatters which other editors may care to read into these dotted commas. It is quite evident that semicolons simply did not occur to Blake in the ordinary course of his letter-writing career. And it may be worth noting that David Erdman (The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, New York, 1956, 687) chooses to read “it: calld” in his diplomatic rendering of 10 Jan. Geoffrey Keynes apparently supposes the dot above the comma utterly accidental, since he ignores it in providing what is perhaps the most acceptable of readings in a modern view: “it, calld” (The Complete Writings of William Blake, Oxford Univ. Press, 1972, p. 811).

| 10 January | 30 January |

| Your very kind & affectionate letter & the many kind things you have said in it; calld upon me for an immediate answer, but it found My Wife & Myself so Ill & My wife so very ill that till now I have not been able to do this duty. The Ague & Rheumatism have been almost her constant Enemies which she has combatted in vain ever since we have been here . . . (1556) | Your letter mentioning Mr Butts’s account of my Ague surprized me because I have no Ague but have had a Cold this Winter. . ..My Wife has had Agues & Rheumatisms almost ever since she has been here . . . (1567) |

If we assume that the news of their health became a little confused in the retelling, we may suppose that the 10 January reference to Blake’s illness and his wife’s Ague and Rheumatism made its way from Butts to James and back to Blake again. And so his clarification, which has a demonstrable relevance if we can date the Butts letter 1803, not 1802. The verbal identity of the last clauses in both excerpts corresponds with their general content to further suggest contiguity in time and reference.

| 10 January | 30 January |

| When I came down here I was more sanguine than I am at present but it was because I was ignorant of many things which have since occurred & chiefly the unhealthiness of the place. (1556) | But I did not mention Illness because I hoped to get better (for I was really very ill when I wrote to him the last time) & was not then perswaded as I am now that the air tho warm is unhealthy. (1568) |

Since he had not mentioned the “unhealthiness” of Felpham to James in a letter which preceded a letter to Butts in which he had so noted it, we must assume that either a year and twenty days or merely twenty days had elapsed since his last to James before the 30 January letter. The fact that he writes Butts in the 22 November 1802 letter that James had told (likely “written”) him that Butts was offended with him makes it very clear that he had had some correspondence begin page 149 | ↑ back to top with James since January 1802 wherein he could have passed on his sense of the unhealthiness of the place.3↤ 3 He did, in fact, enclose a letter to James in 22 Nov. (1566). And from what he says about his correspondence with Butts “the last time,” it is highly unlikely that the 22 November letter came between 10 January and 30 January as that last letter. The parenthetical emphasis on his illness, while it seems to qualify the relatively negligible “Cold” initially implied, therefore comes closer to the “so Ill” emphasis of the 10 January letter.

| 10 January | 30 January |

| I am now engaged in Engraving 6 small plates for a New Edition of Mr Hayleys Triumphs of Temper. . . (1556) | I am now Engraving Six little plates for a little work of Mr. H’s. . . (1568) |

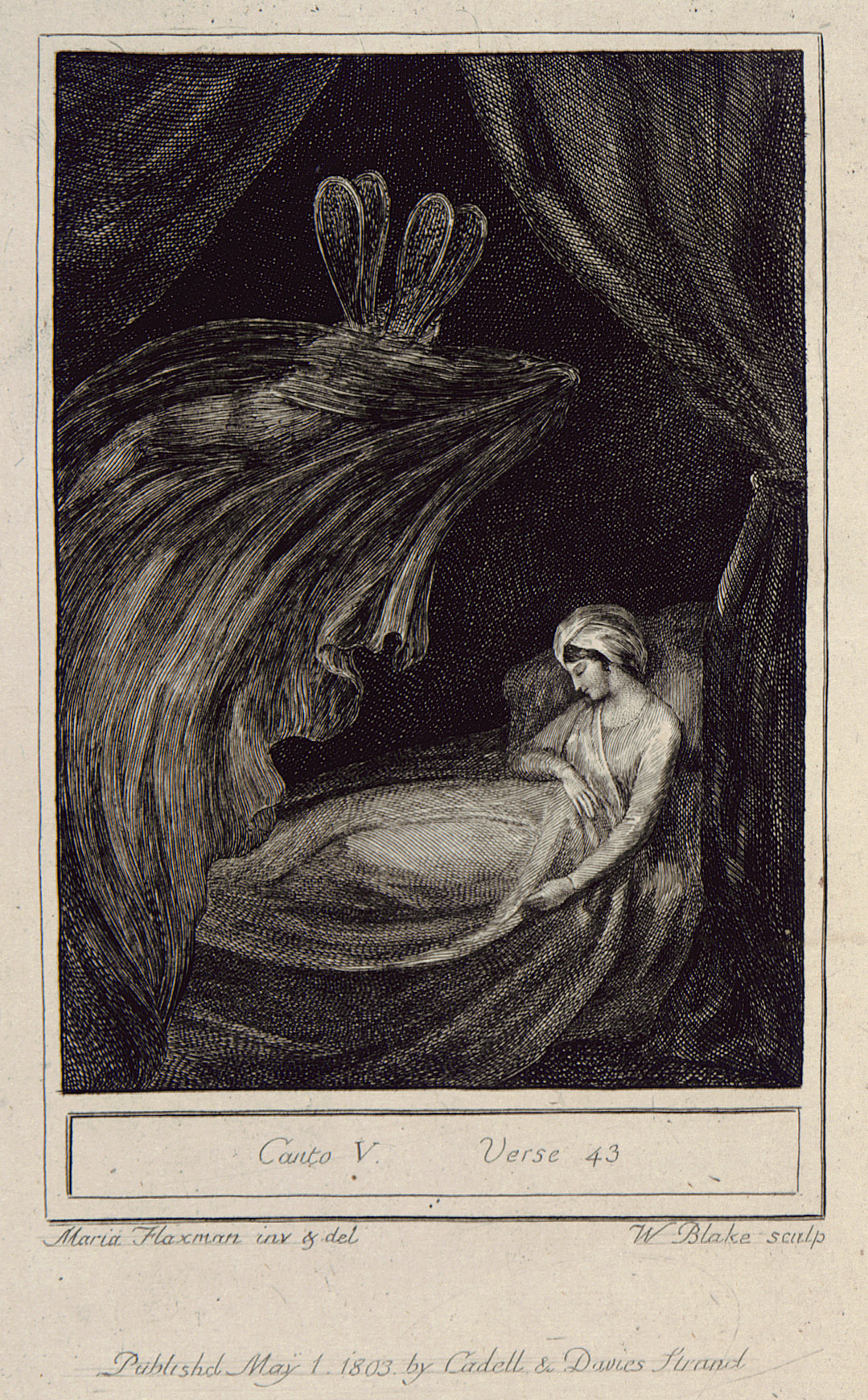

Again content and verbal correspondences would seem to coalesce the references into the same time period. The “indefatigable” Blake could linger over a work in contemplation but, once under way, these six little plates could hardly have taken over a year in the execution, particularly since Hayley was obviously (so the 10 January letter) pressing him to “the meer drudgery of business” with “intimations that if I do not confine myself to this I shall not live” (1557). The volume referred to in both letters would then seem to be the twelfth edition of the Triumphs, published by the summer of 1803.4↤ 4 The 1 May imprint on the Triumphs plates comfortably allows the inference from a redated 10 Jan. letter that Blake was working on them through the winter and early spring of 1803. I am indebted to Robert Essick for conveying this information to me.

| 10 January | 30 January |

| My unhappiness has arisen from a source which if explord too narrowly might hurt my pecuniary circumstances. As my dependence is on Engraving at present & particularly on the Engravings I have in hand for Mr H. . . . You will understand by this the source of all my uneasiness. This from Johnson & Fuseli brought me down here & this from Mr. H will bring me back again. . . . (1557) | I did not mention our Sickness to you & should not to Mr Butts but for a determination which we have lately made namely To leave This Place because I am now certain of what I have long doubted Viz t[hat] H. . . . will be no further my friend than he is compelld by circumstances. . . . he thinks to turn me into a Portrait Painter as he did Poor Romney . . . This is the uneasiness I spoke of to Mr Butts but I did not tell him so plain . . . I told Mr Butts that I did not wish to Explore too much the cause of our determination to leave Felpham because of pecuniary connexions between H & me— (1567) |

We often wish that we could unite again in Society & hope that the time is not distant

when we shall do so, being determined not to remain another winter here but to return to

London.

I hear a voice you cannot hear that says I must not stay I see a hand you cannot see that beckons me away. (1558) |

But my letter to Mr. Butts appears to me not to be so explicit as that to you for I told you that I should come to London in the Spring. . . But sinœ I wrote yours we had made the resolution of which we informd him viz to leave Felpham entirely. (1568) |

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Once again nearly identical words are used to express in both letters Blake’s determination to leave Felpham begin page 150 | ↑ back to top before “another winter” or “in the Spring,” with specific reference to the 10 January letter unmistakable in the paraphrase to James of his unwillingness “to Explore too much” his reasons for leaving “because of pecuniary connexions between H & me.” The use of “pecuniary,” “explord,” “uneasiness,” “determind” in 10 January, all echoed in 30 January, abet the general statement of both letters—Blake is coming back to London before another winter—to fairly well dispose of the 1802 date without other evidence. But even here we may note besides the relative lack of explicitness assigned to the Butts letter in the letter to James seems justified by the cautious innuendo and suggested fears of 10 January, even to the Tickell distich with which the excerpt concludes. The reference to the more explicit letter to James suggests that it was written fairly recently, though before the less explicit letter that he parallels it with. The letter to James could well be the one referred to in the P.S. to the second letter of 22 November 1802. And, while of course possible, Blake’s clear intention to leave Felpham the following winter would dangle like a broken purpose nowhere justified in subsequent correspondence if the present 1802 dating is retained.

Another parallel or two between these letters may be best considered along with the two letters to Butts of 22 November which now separate, in time and space, 10 January and 30 January. As already noted, the November letter begins with Blake’s concern that Butts was offended with him. Or so James had “told” him. He then offers a survey of his two year study of chiaroscuro which eventually comes to relevant focus on the “Pictures” he has done for Butts (1560-61). He concludes the letter by writing that he is sending “Two Pictures” to Butts which he hopes will gain his employer’s approval (1562). In the second letter, which seems to have been enclosed with the first, he again refers to these same “two little pictures” (1566). In the 10 January letter he provides a “P.S.” in which he thanks Butts for his “Obliging proposal of Exhibiting my two Pictures” (1559). He also promises to finish “the other,” since he’d been provided—as he reminds Butts in the 22 November letter—with “three” canvasses. Or, rather, he is reminding Butts of the “other” canvas in the 10 January letter if, and only if, that letter can be dated 1803. But, unless we somehow suppose that the two pictures and a third canvas referred to in 22 November and the two pictures plus an “other” yet to be done mentioned in 10 January really refer to two different sets of two completed and one projected picture—unless we make that inference, we seem obliged to correct the date in lieu of straining coincidence to a breaking point.5↤ 5 This third canvas might have been filled in, on Butts’s reply to Blake’s request for instructions, with the “Picture of the Riposo, which is nearly finished much to my satisfaction” by 25 Apr. 1803 (1571) and then sent to Butts with the letter of 6 Jul. In the 10 Jan. P.S. he is apparently working on “the other,” having (if we can accept the 1803 date) been given the subject and implicit go-ahead he had asked for in 22 Nov. In his Aug. letter to Butts he apologizes for having omitted to thank Butts for “offering to Exhibit my 2 last Pictures in the Gallery in Berners Street” (1577). He then quotes the thank-you which he had written in a “rough sketch” of what might well have been the 6 Jul. letter. The quotation would have fit in well enough after the description of the “Riposo” at the start of that letter. It is clear from 22 Nov. (1563) that Blake distinguished between the three canvasses which he had brought with him to Felpham (for the two pictures completed and the one in prospect) and the “Drawings” which he is also doing for Butts. He so distinguishes the “Riposo” from the seven drawings he has “on the Stocks” for Butts as of 6 Jul. (1574) and which he sent to him 16 Aug. (1577). The likelihood is that the “Riposo” was the subject of the third canvas which Blake associated with the two pictures of his first thank-you to Butts in the 10 Jan. P.S. Whether Blake had forgotten his original thanks to Butts or reiterated it when the “Obliging proposal” had gained the concrete focus of a specific gallery is unclear but probably immaterial.

Furthermore, we should first note that in the second of the 22 November letters he directly asks Butts to tell him “in a Letter of forgiveness if you were offended & of accustomed friendship if you were not” (1563). And in light of that request, we should then consider whether the beginning of the 10 January letter, referring to Butt’s “very kind & affectionate Letter,” does not in fact refer to the response which the 22 November letter had solicited. Blake notes that he should have answered before 10 January whatever kind letter Butts sent him either at some indefinite time before 10 January 1802 or between 22 November 1802 and 10 January 1803. If Butts had made a fairly prompt reply to Blake’s clear plea for one, we could suppose a time lapse of a month and a half a sufficient delay to call for the excuse of illness which in fact we do have in the 10 January letter. But, to move out of the polypus of what may seem a circular argument, we may again return to the substantive matter of the pictures. What pictures, if not the two enclosed in the 22 November letter, is Blake referring to in 10 January when he writes Butts that “Your approbation of my pictures is a Multitude to Me . . . ” (1556)?

The final significant bit of evidence from the 22 November letter which may be relevantly collated with both 10 January and 30 January appears in Blake’s explanation to Butts of his long silence: “ . . . I have been very Unhappy & could not think of troubling you about it or any of my real friends . . . ” (1561-62). In the 10 January letter he is clearly responding to a concern for his happiness which could very well have been elicited from Butts by the 22 November confession: “But you have so generously and openly desired that I will divide my griefs with you that I cannot hide what it is now become my duty to explain—My unhappiness has arisen . . . ” etc. (1557). In both the 10 January and 30 January letters he not only defines his unhappiness in comparable terms which suggest their proximity in time but reiterates more specifically his 22 November disinclination to burden his friends by “dividing” his griefs with them them: “ . . . I should not have troubled You with this account of my spiritual state unless it had been necessary in explaining the actual cause of my uneasiness into which you are so kind as to Enquire, for I never obtrude such things on others unless questiond . . . ” (10 January; 1558); “I never make myself nor my friends uneasy if I can help it” (30 January; 1567). Again one may note that the “question” which the 10 January letter required was in fact solicited by the 22 November letter.

While there may be other correspondences or incongruities to favor the case I am advancing, these seem sufficient to decide it.6↤ 6 In his 16 Aug. 1803 letter Blake asks Butts about his eyes: “I nver sit down to work but I think of you & feel anxious for the sight of that friend whose eyes have done me so much good . . . ” (1577). In 10 Jan. he expresses a comparable (and apparently initial) concern: “But what you tell me about your sight afflicted me not a little . . . ” (1556). While Butts’s eye problem could have extended over twenty months, from Jan. 1802 until Aug. 1803, the chances are that it did not. By drawing these kindred expressions of concern a year closer, we would focus them on the less chronic and more remediable affliction which Blake seems to be referring to. The digital strength of the “2” which Blake wrote cannot, I think, hold up the weight of the internal evidence arguing against its retention. I believe future editors should allow the change definitive standing, while future biographers may care to readjust their perspective on Blake’s overt expressions of his dissatisfaction with Hayley and Felpham.