minute particular

W. J. LINTON’S TAILPIECES IN GILCHRIST’S LIFE OF WILLIAM BLAKE

In his Bibliography of William Blake Sir Geoffrey Keynes made an attempt to identify all of Blake’s designs from which W. J. Linton made his wood engravings for the 1863 edition of Alexander Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus”: in Volume I four full-page cuts (three from the Job series and “Plague”) and fifty-six smaller cuts in the text; in Volume II seven small wood engravings in the text.1↤ 1 (New York: The Grolier Club, 1921), pp. 328-31. Keynes erroneously lists a Linton cut on II, 1, and II, 2; they are on II, ix (unnumbered page), and II, 1, respectively. The frontispiece of Linnell’s 1827 portrait of Blake is apparently the only engraving not done by Linton: it is by C. H. Jeens. Logically assuming from the Gilchrist titlepage statement, “Illustrated from Blake’s own works, in facsimile by W. J. Linton,” that all of these cuts (other than those “in photolithography” and the “few” Blake “original plates”) were based on, or engraved after, Blake originals, Keynes nevertheless lists ten in Volume I and three in Volume II as unidentified (he ignored the one on page 111 of Volume II)—all rather miniscule chapter tailpieces. In Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) G. E. Bentley, Jr. makes no comment about Linton’s contributions to the Life, and Robert Essick in his “Finding List of Reproductions of Blake’s Art,” Blake Newsletter, 5 (1971), 1-160, lists only Linton’s full-page cuts—properly so given the purpose of the list.

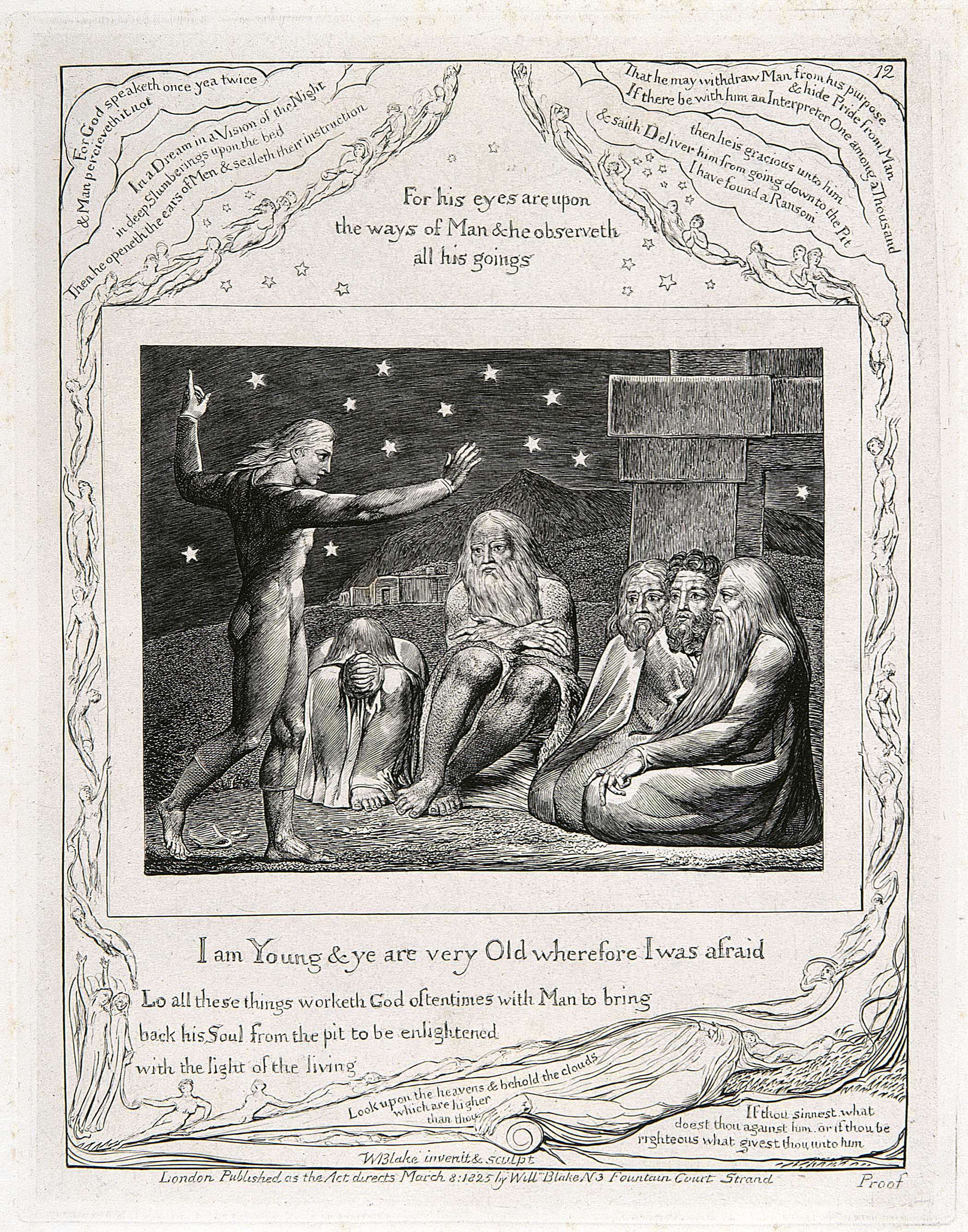

In my recent research toward an article on Linton and Blake (forthcoming in the Bulletin of Research in the Humanities) I re-examined all of Linton’s contributions to Gilchrist’s Life and have managed to identify all but three of the tailpieces unidentified by Keynes. They form an interesting pattern, one that reflects certain problems Linton had with Dante Gabriel Rossetti over the inclusion in the Gilchrist of photolithographed reproductions of the Job designs. Of the thirteen tailpieces (fourteen including the one on page 111 of Volume II) the sources of which Keynes could not identify, nine are from the border design of Plate 12 of the Job series (see illus. 3): ↤ 2 None of these appears in the 1880 edition of Gilchrist’s Life.

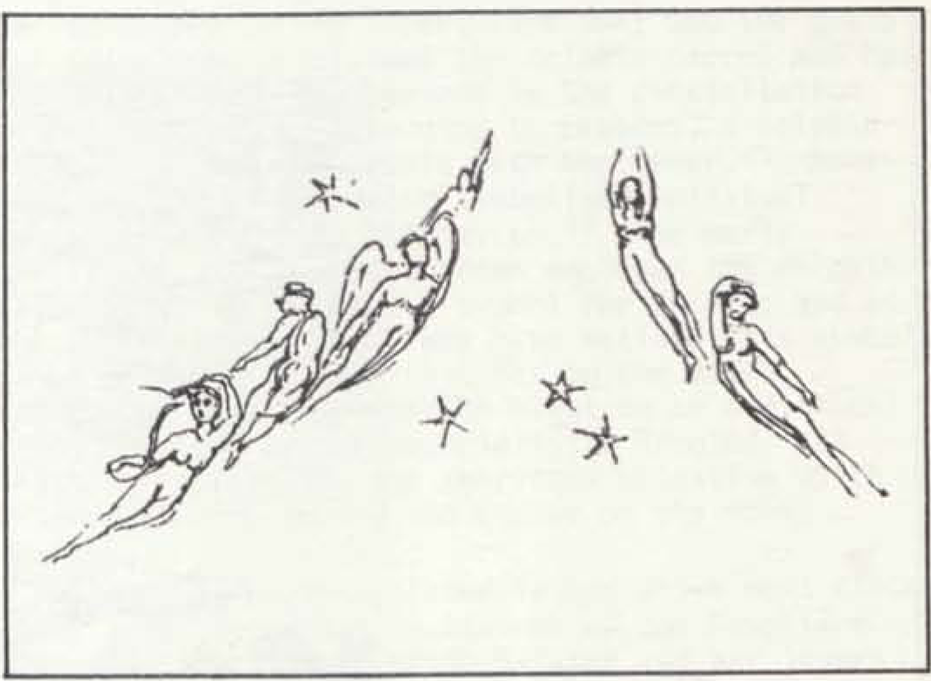

Volume I, page 11: the sixth figure from the top right of Job 12, reversed.

Volume I, page 42: figures at bottom right.

Volume I, page 118: figures at bottom left.

Volume I, page 126: figures at top center.

Linton added to, and changed, Blake’s stars, designing them in his own characteristically spiky manner (see illus. 1).

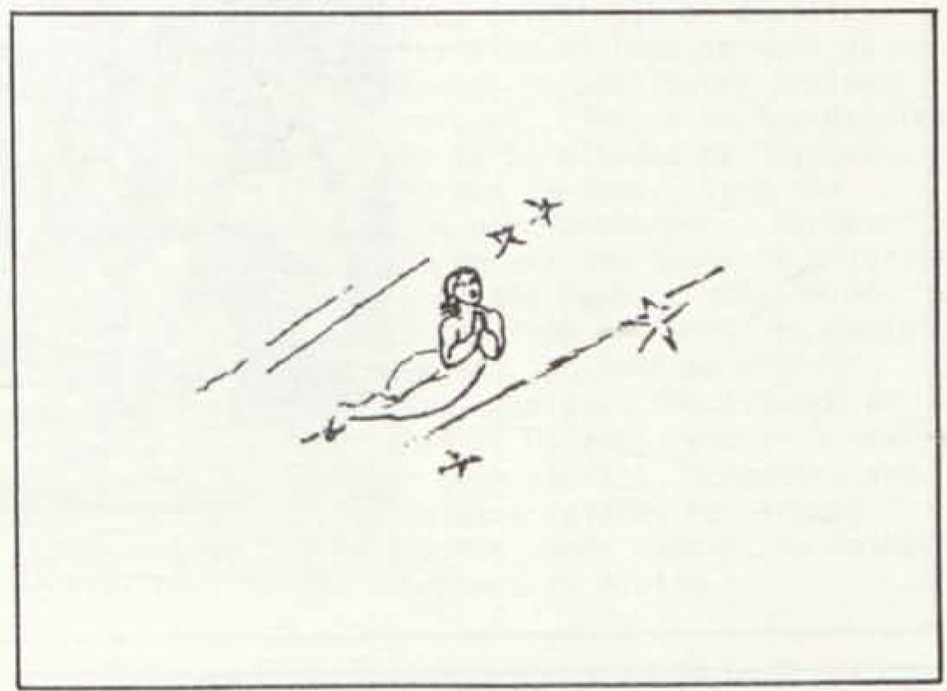

Volume I, page 233: fifth figure from top right, reversed, again with Linton’s spiky stars (see illus. 2).

Volume I, page 248: third figure from top left.

Volume II, page 97: third figure from bottom right, turned sideways.

Volume II, page 111: figure just above center right.

Volume II, page 116: figure at upper-right corner of main design box.2

Elsewhere in Gilchrist we have Linton’s wood engravings of Job Plates 5, 8, and 14 (all full-page, the last excluding Blake’s border designs

except for the corner angels), the top half of the border design of Plate 18, and the circular part of the main boxed design of Plate 15. From Rossetti’s correspondence with Anne Gilchrist (who had taken over the editing of the Life at the death of her husband) as the volumes were nearing completion, we learn that, despite their plans to include photolithographs of the entire Job series, Linton (who had been a part of the project as early as 18613↤ 3 On 20 April 1861 Rossetti had written to Alexander Gilchrist to suggest a friend of his to work on the Blake illustrations: “I have been thinking that if you are still unprovided with a satisfactory copyist (or a sufficiency of such) for the Blakes,—Mrs. Edward [Burne] Jones would be very likely to succeed. This occurred to me shortly after seeing you the other day, but I did not see her till today, when I mentioned the matter to her. I hope I did not do wrong, but she is too intimate a friend to make it awkward for me if you and Linton cannot entertain the idea”—Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, ed. Oswald Doughty and John R. Wahl (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), II, 396. This seems to suggest that Linton originally may have planned (or been hired) only to supervise (and/or execute a few of) the engravings for the Life. In any case, nothing seems to have come of the matter. and, one would presume, knew about the photolithography idea) went ahead and executed his own wood engravings of the entire series.4↤ 4 This is an assumption on my part. Rossetti’s words, in the letter to Mrs. Gilchrist quoted below, are “the Job Plates which he [Linton] copied.” It is possible, then, that these plates are the five I have already noted—though Linton’s pillaging of the border design of Plate 12 argues that he did more than five.It is not clear what led to this confusion, for in February 1863 Linton had written to Rossetti “about the illustrations” and Rossetti had even taken the trouble of visiting Linton to consult with begin page 209 | ↑ back to top

begin page 210 | ↑ back to top him about them.5↤ 5 Letter from Rossetti to Mrs. Gilchrist, dated only “Feb. 1863,” in Letters, II, 477. There is a hint, however, that there was some earlier difficulty over the Job project. On 13 December 1862 William Michael Rossetti, who was also very much a part of the Gilchrist Life enterprise, wrote to Mrs. Gilchrist: “I am truly sorry that so much anxiety to you has been involved in the Job affair”—Letters of William Michael Rossetti, ed. Clarence Gohdes and Paull F. Baum (Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 1934), p. 11. I can find no other reference to an apparent problem—though, of course, Linton may have been the cause. Dante Gabriel once said of him, “He keeps stomach-aches for you” even if he was the best engraver around—Oswald Doughty, Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A Victorian Romantic (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1949), p. 215. At about the same time Rossetti received from Mrs. Gilchrist the Job photolithographs which he said pleased him “much—being, though blurry, very full of colour, and not losing perhaps by reduction but getting concentrated in a pleasant way.”6↤ 6 Another letter of February 1863 from Rossetti to Mrs. Gilchrist, in Letters, II, 477. Taken together, these letters suggest that the plan to photolithograph the Jobs was one of long-standing. The only problem with Linton involved a design he engraved for the titlepage, the original of which Rossetti apparently had not seen, for upon receiving it (or, more likely, a proof of it) from Mrs. Gilchrist he returned it to her for some “amendment,” saying he would venture “to write a word to Mr. Linton suggesting the removal of the cut, which surely is no facsimile from anything of Blake’s, but a sort of design by some one else.” Then, as if doubting his authority, he added a postscript to this letter: “Would you perhaps send the Titlepage on to Mr. Linton—to explain better what I mean.”7↤ 7 Letter from Rossetti to Mrs. Gilchrist, dated only “1863” but apparently later than those already cited, in Letters, II, 482. But Rossetti, perhaps reinforced by Mrs. Gilchrist in a letter not extant, did nevertheless “advise” Linton to omit “that insane cut in the title page.”8↤ 8 Letter of 1863 from Rossetti to Mrs. Gilchrist, in Letters, II, 483. With all this to-do there is no evidence in the letters of Rossetti or Mrs. Gilchrist to suggest any misunderstanding about the Job series. When Linton sent Rossetti the (apparently) final list of illustrations to the volumes, then, and included in it all his copies of the Jobs, Rossetti was in a quandary about what to do with them since the photolithographs were ready to go. He quickly wrote Mrs. Gilchrist: “I see he still includes the Job Plates which he copied, in spite of the photolithographs which might be considered to supersede them.”9↤ 9 Letters, II, 489. This “list” was perhaps that from which the “List of Illustrations” (Gilchrist, Life, I, xiii-xiv) was to be made, for earlier Rossetti had written to Mrs. Gilchrist that “Mr. Linton has sent me a list of the illustrations [n.b.: not his] which must come in somewhere. I will see with the Printer” (Letters, II, 488). I have been unable to learn whether the list has survived. What finally emerged is clearly a kind of compromise, Linton no doubt insisting that at least some of his Jobs be included even along with the full photolithographed set,10 Rossetti urging Mrs. Gilchrist (in the letter just quoted) that “it seemed a pity to leave them out after the trouble and expense.”10↤ 10 The listing of Linton’s Job plates in the “List of Illustrations” following the contents pages of the Life is accompanied by the notation: “Two only the centres the same size as the originals [i.e. Job 5 and 14], and one reduced to show border [i.e. Job 8]. These Plates are given in duplicate in the Series rendered by Photolithography.” There is no notation accompanying the listing of Linton’s engravings of Job 15 and 18. Why all the rest of Linton’s Jobs that were included, piecemeal, as tailpieces turn out to be one, Plate 12, I cannot say. Perhaps that plate was, simply, one of his favorites; perhaps, even more simply, it was the only other one that he actually engraved.Of the other five tailpieces Keynes could not identify, I can be certain of only one, that on page 269 of Volume I, which is the lower-left figure on the titlepage of Visions of the Daughters of Albion. That on page 160 of Volume I (see illus 4) may be a version (reversed) of the reclining figure in the center of Plate 4 of Europe, or possibly of the second figure from the bottom right of Job 12, or even more likely to my eye, the figure to the left of the word “Albion” on the titlepage of Visions of the Daughters of Albion—though I have no great confidence in these sources since all of the other tailpieces are exact replicas. For those on pages 304 and 367 of Volume I, and 24 of Volume II (see illus. 5, 6, 7), I cannot find even good analogues. Perhaps these last were taken from the excised titlepage design; or they are examples of Linton’s idea of a Blakean figure or design; or they are taken from other of Linton’s own voluminous work (the one on II, 24, for example, is strongly reminiscent of details in several of Linton’s wood engravings for Harriet Martineau’s A Description of the English Lakes, 1858). In any case, Linton’s entire role in the Gilchrist project, as well as his own fascinating Blake-like career, deserve considerably more scholarly and critical attention than they have been accorded to date.