article

begin page 185 | ↑ back to topJOHN TRIVETT NETTLESHIP AND HIS “BLAKE DRAWINGS”

When J. T. Nettleship died in 1902, he was a successful artist who had specialized in wild animal subjects. According to The Magazine of Art, “He took as his models the animals which have not come under human domination, the larger beasts of prey, fierce and untameable; and he sought habitually to realise all their strenuous energy and ferocity.”1↤ 1 Anon., “J. T. Nettleship, Animal Painter,”[e] The Magazine of Art, 1903, p. 75. From 1874 until 1901 he exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy as well as at the New Gallery and the Grosvenor Gallery.2↤ 2 See Algernon Graves, Dictionary of Artists (New York: Burt Franklin, 1970 [reprint of 1901]); The Magazine of Art, 1903, p. 77. 77. He also published two books: Essays on Robert Browning’s Poetry3↤ 3 London: Macmillan and Co., 1868. and George Morland and the Evolution from Him of Some Later Landscape Painters.4↤ 4 London: Seeley & Co., 1898. His daughter Ida had married Augustus John. To his contemporaries Nettleship could appear at the same time to be “our later Landseer” and “a lord of Bohemia.”5↤ 5 “Sigma” [Julian Osgood Field], Personalia (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1903), p. 215; The Art Journal, 1907, p. 251. Yet in the early 1870s, at the beginning of his career, Nettleship had created works of a much different kind than those which made his reputation. “It is to be regretted that none of the designs conceived in this period was ever properly finished,” wrote James Sutherland Cotton, who had known Nettleship. “They included Biblical scenes, such as ‘Jacob wrestling with the Angel,’ and ‘A Sower went forth to sow,’ which have been deservedly compared with the work of William Blake.”6↤ 6 DNB, Supplement 1901-11 (1927), s.v. Nettleship’s early work was indeed heavily influenced by Blake, and when he came to frequent the Rossetti circle, he brought his “Blake drawings” (as they came to be known in the Nettleship family) with him.

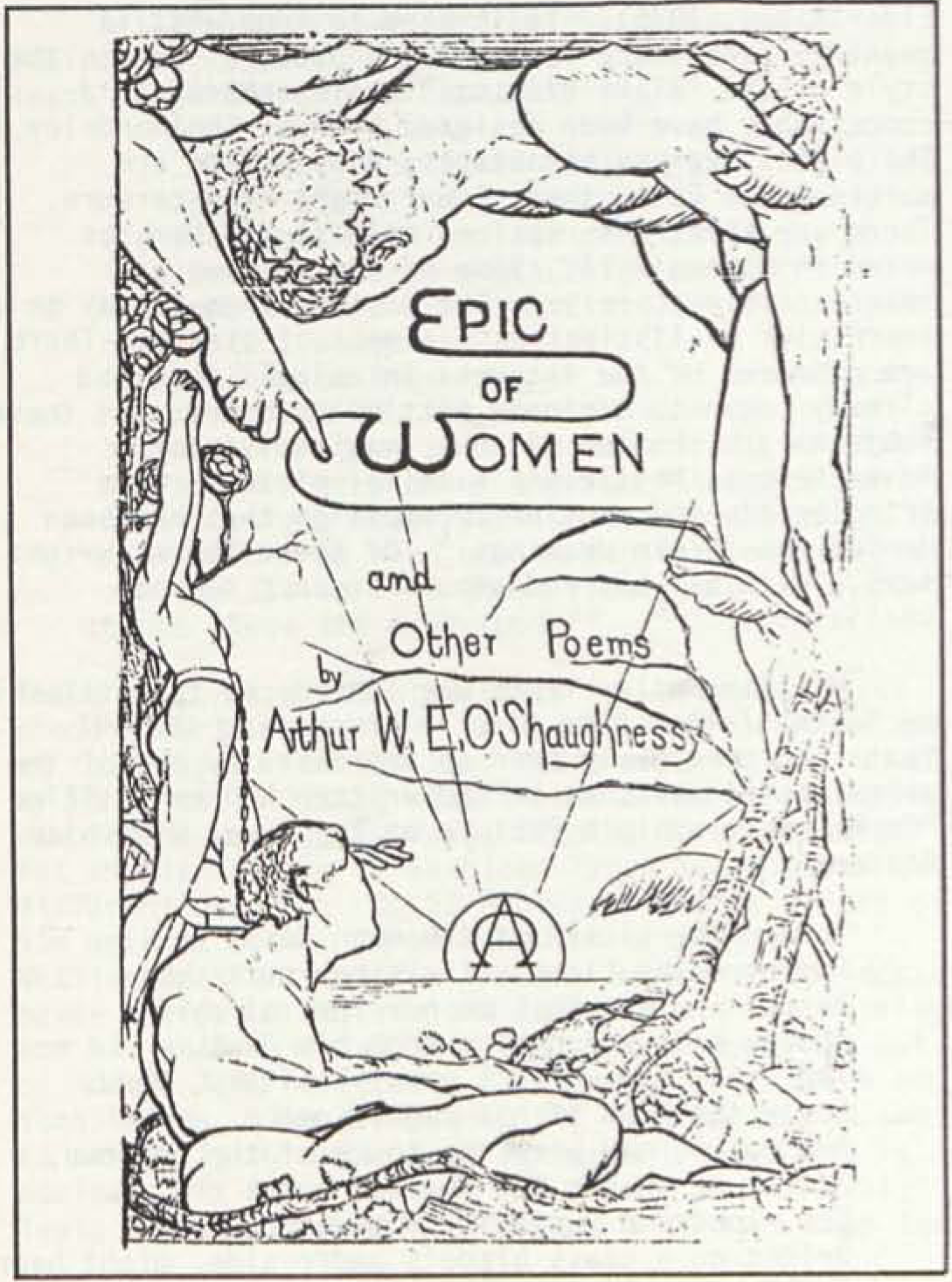

According to William Michael Rossetti, Nettleship may have been introduced to the Rossettis by mutual friends—John Payne or Arthur O’Shaughnessy, both poets. “As he had not from the first been destined for the pictorial profession,” wrote Rossetti of Nettleship, “he was older than most beginners, twenty-seven. He was an intellectual young man, full of abstract conceptions: such a subject as ‘God Creating Evil’ had no terrors for him—or I should rather say, not any such terrors as dissuaded him from designing it.”7↤ 7 Some Reminiscences of William Michael Rossetti (London: Brown, Langham, 1906), II, 326. Nettleship studied painting at the Slade school, but the influence of Blake may have come to him through “The Brotherhood,” a group that included John Butler Yeats and Edwin Ellis.8↤ 8 As suggested to me by Professor Ian Fletcher, who first called the Nettleship drawings to my attention and to whom I an grateful for his valuable assistance and encouragement. In this circle Nettleship would also have met O’Shaughnessy, whose Epic of Women he illustrated in 1870. At any rate, by the time Nettleship met Dante Gabriel Rossetti, he had already acquired a Blakean pictorial vocabulary. According to Gale Pedrick, he produced “sketches of a Blake-like kind [which] amazed and delighted Rossetti with their audacity of treatment.”9↤ 9 Life with Rossetti (London: Macdonald, 1964), p. 103. Until recently it was difficult to assess the impact upon Rossetti and, later, upon W. B. Yeats of Nettleship’s “Blake drawings,” as they were the property of the Nettleship family. Now in the collection of the University of Reading, their importance as early examples of the influence of Blake’s art can at last be appreciated.10↤ 10 I wish to thank Dr. J. A. Edwards, Archivist of the University of Reading, for enabling me to see this material.

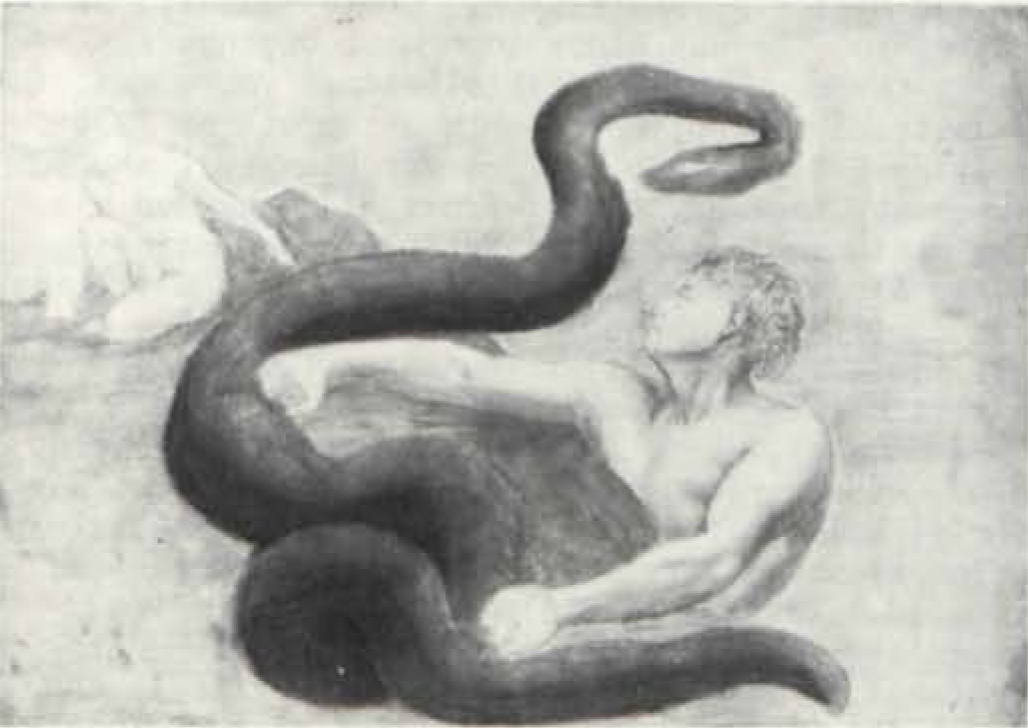

Nettleship’s early drawings are varied in style as in subject matter. Some are obviously indebted to Blake, while others are more conventionally Victorian. Among the former are a series involving naked human figures and a huge serpent, reminiscent of Blake’s Los, Enitharmon, child Orc and Orc begin page 186 | ↑ back to top

At about the same time that he executed the “Blake Drawings,” Nettleship did five illustrations for Arthur W. E. O’Shaughnessy’s Epic of Women and Other Poems, the poet’s first book, published by the enterprising John Camden Hotten12↤ 12 On Hotten, see my article “John Camden Hotten, A. C. Swinburne, and the Blake Facsimiles of 1868,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 79 (1976), 259-96. in 1870. In these designs the influence of Blake, though apparent, is further subordinated to Nettleship’s own manner. The title page shows a male nude in the foreground, reclining in a garden-like setting and staring over the sea to the rising sun. A titanic nude male wearing a chaplet of stars leans down pointing from the top of the picture; a female figure on the left with a chain fastened to her waist raises her arms, hands clasped, upward. None of these figures is copied from Blake, but the effect of the whole suggests the illustrations to Night Thoughts. Two female figures in other designs recall Oothoon in begin page 187 | ↑ back to top

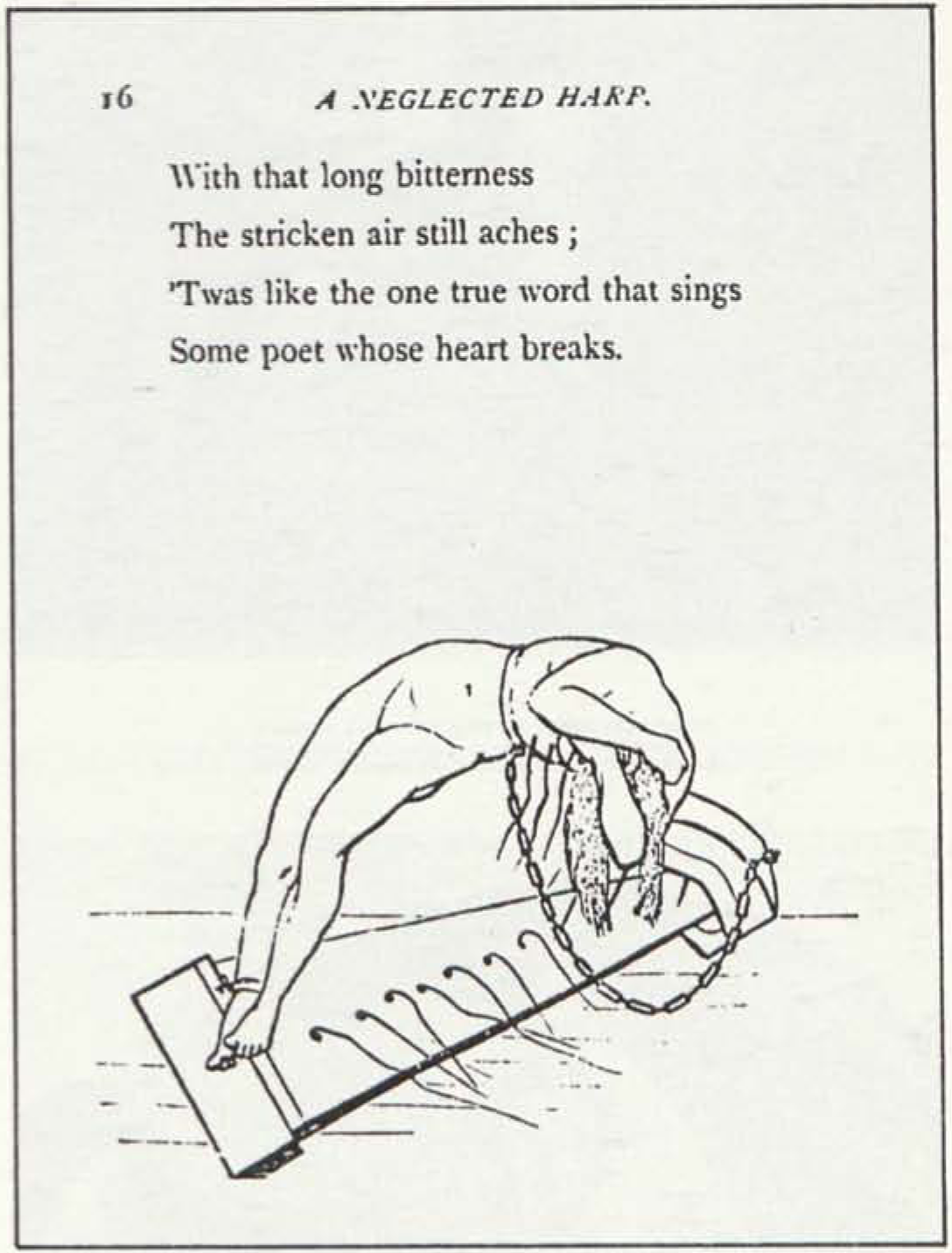

Nettleship did illustrate, or partly illustrate one more book in the 1870s—Emblems by Alice Cholmondeley, “Revised by J. J. Nettleship” [sic] and edited by Reginald Cholmondeley (London: Smith,

begin page 188 | ↑ back to topWilliam Butler Yeats was introduced to Nettleship by Yeats’ father some time in the period 1887-91. Yeats had previously been so impressed by one of the animal paintings that he had written a poem entitled “On Mr. Nettleship’s Picture at the Royal Hibernian Academy”: ↤ 17 First published in the Dublin University Review for April 1886, p. 3. MS version cited here from The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. P. Allt and R. K. Alspach (New York: Macmillan, 1957), pp. 688-89. Reprinted by permission.

Yonder the sickle of the moon sails on,Yeats did not reprint this poem, and it is easy to see why: it is too conventionally rhetorical, the analogy of the lion’s eye to the circle of the outer law and to the orb of the living heart is too obviously contrived, and the last line seems produced by the will to end with an emphatic flourish. Yeats was to change his mind, too, about the quality of Nettleship’s animal paintings—by the time he met the artist, Yeats considered him “once inventor of imaginative designs and now a painter of melodramatic lions.”18↤ 18 “Four Years/1887-1891,” The Dial, 71 (1921), 81. Yeats tells of how he was impressed by the courage and asceticism of Nettleship, by then a reformed alcoholic who incessantly drank cocoa. ↤ 19 “Four Years,” p. 83.

But here the Lioness licks her soft cub

Tender and fearless on her funeral pyre;

Above, saliva dropping from his jaws,

The Lion, the world’s great solitary, bends

Lowly the head of his magnificence

And roars, mad with the touch of the unknown,

Not as he shakes the forest; but a cry

Low, long and musical. A dew-drop hung

Bright on a grass blade’s under side, might hear,

Nor tremble to its fall. The fire sweeps round

Re-shining in his eyes. So ever moves

The flaming circle of the outer Law,

Nor heeds the old, dim protest and the cry

The orb of the most inner living heart

Gives forth. He, the Eternal, works His will.17

He thought [Yeats writes] that any weakness, even a weakness of the body, had the character of sin and while at breakfast with his brother, with whom he shared a room on the third floor of a corner house, he said that his nerves were out of order. Presently, he left the table and got out through the window and on to the stone ledge that ran along the wall under the window-sills. He sidled along the ledge, and turning the corner with it, got in at a different window and returned to the table. ‘My nerves,’ he said, ‘are better than I thought.’19begin page 189 | ↑ back to top

Nettleship, responding to the young poet’s admiration, showed Yeats some of his early drawings. Yeats responded enthusiastically: ↤ 20 “Four Years,” pp. 81-82.

. . . They, though often badly drawn, fulfilled my hopes. Something of Blake they certainly did show, but had in place of Blake’s joyous intellectual energy a Saturnian passion and melancholy. God Creating Evil, the death-like head with a woman and a tiger coming from the forehead which Rossetti—or was it Browning?—had described as ‘the most sublime design of ancient or modern art’ had been lost, but there was another version of the same thought, and other designs never published or exhibited. They rise before me even now in meditation, especially a blind Titian-like ghost floating with groping hands above the tree-tops.20These pictures stimulated Yeats to write his first piece of art criticism. It is not clear what became of this essay. In The Dial Yeats says it was rejected by an editor “lifting what I considered an obsequious caw in the Huxley, Tyndall, Carolus Duran rookery.”21↤ 21 “Four Years,” p. 82. Yet in his letters to Kathleen Tynan Yeats gives a different account. On 28 February 1890 he writes of his work at hand: “Then comes an article on Nettleship’s designs for the Art Review—great designs never published before—and later an article on Blake and his anti-materialistic Art, for somewhere”; but on 1 July 1890 he reports “I am working on Blake and such things. The Art Review has come to an end and so unhappily my article on Nettleship’s designs is useless.”22↤ 22 The Letters of W. B. Yeats, ed. Allan Wade (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954), pp. 150, 154. Like the original “God Creating Evil,” Yeats’s essay on Nettleship appears to have been lost.

Yeats made on effort to re-enlist Nettleship in the service of visionary art. He commissioned the artist to draw the frontispiece for the first edition of The Countess Kathleen and Various Legends and Lyrics, published by T. Fisher Unwin in 1892. The resulting picture of Cuchillin fighting the waves was so lacking in conviction that Yeats was not encouraged to make a second attempt “to restore one old friend of my father’s to the practice of his youth.”23↤ 23 “Four Years,” p. 80. England’s second Landseer returned to his animal painting. “Nettleship,” concluded Yeats, “had found his simplifying image, but in his painting had turned away from it. . . . ”24↤ 24 “Four Years,” p. 83.

APPENDIX I: Nettleship’s “Blake Drawings” at the University of Reading

All are pencil drawings unless otherwise indicated.

MS 7/27/1. 26 × 19 cm. This drawing is actually by E. J. Ellis, apparently a study for a design published in Ellis’ Seen in Three Days (London: sold by Bernard Quaritch, 1893). In the published version the male figure has been changed to an old man with great wings and a long white beard. Both versions are obviously indebted to Blake’s designs for Young’s Night Thoughts.

begin page 190 | ↑ back to top begin page 191 | ↑ back to top begin page 192 | ↑ back to topMS 7/27/2r and 2v. Pencil, India ink, water color. 13 × 17 cm. Both are drawings of a large feline, possibly a lioness.

MS 7/27/3r. Pencil, pen, and ink. 25 × 18 cm. An

angel with huge wings dancing with a young woman.MS 7/27/3v. Two faintly sketched figures, one male, one female.

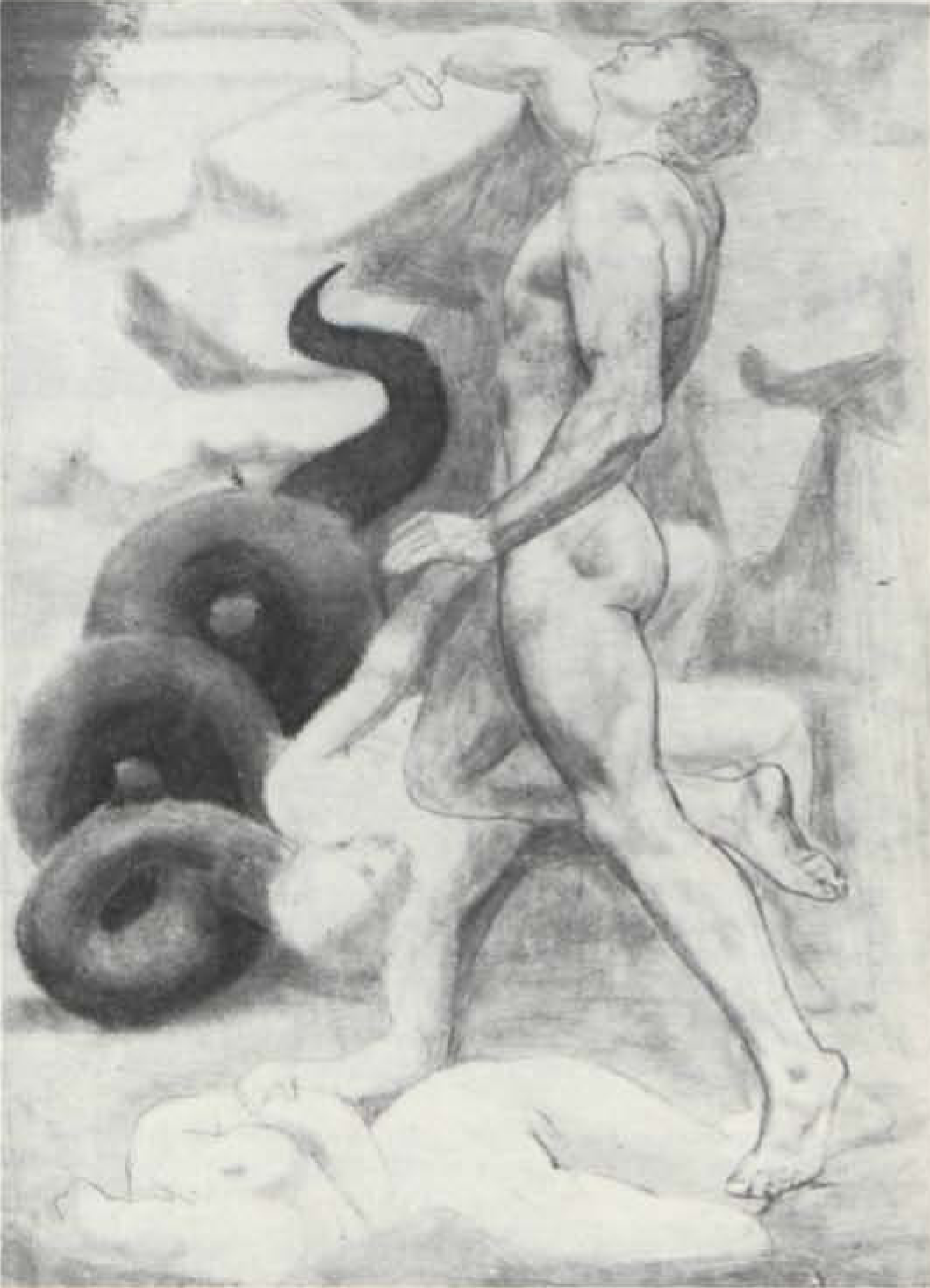

MS 7/27/4. 25 × 36 cm. A male figure is about to kill a supine figure with a sword. At the lower right is the head (and knees?) of a woman whose hair rises to twine about the swordsman’s wrists and thighs.

MS 7/27/6. 36 × 26 cm. The “family group.” The man, awkwardly holding a sword in his right hand, severs the head of a giant serpent. The woman and the boy support the man on either side.

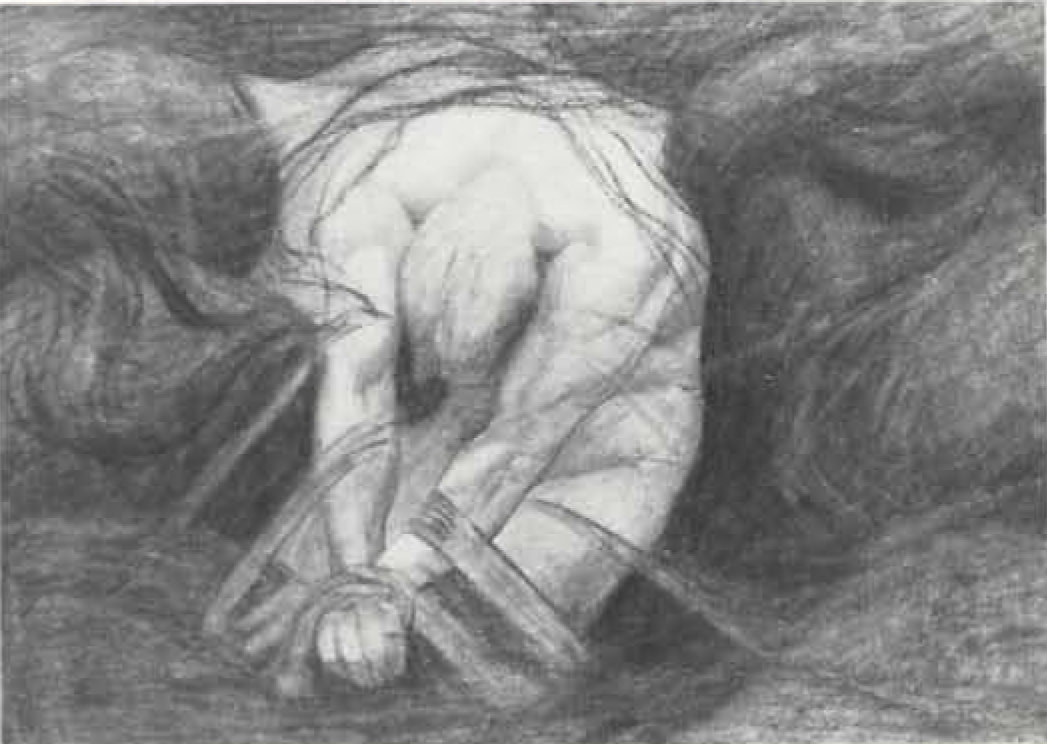

MS 7/27/7. 26 × 36 cm. A powerful male figure bound down as it were by the stems of vegetation.

MS 7/27/8r. 26 × 36 cm. A man drawing a sword and a boy with a knife on a staircase.

MS 7/27/8v. A man and a boy, sketchily drawn.

MS 7/27/9. 26 × 36 cm. The “family group.” Man begin page 193 | ↑ back to top struggles with gigantic serpent, woman and (faintly sketched) boy look on. Crescent moon at right.

MS 7/27/10r. 26 × 36 cm. An old man sits hunched in a throne-like chair. A young woman sits at his left. Behind him is a portrait of a mother and child.

MS 7/27/10v. A lioness and parts of another.

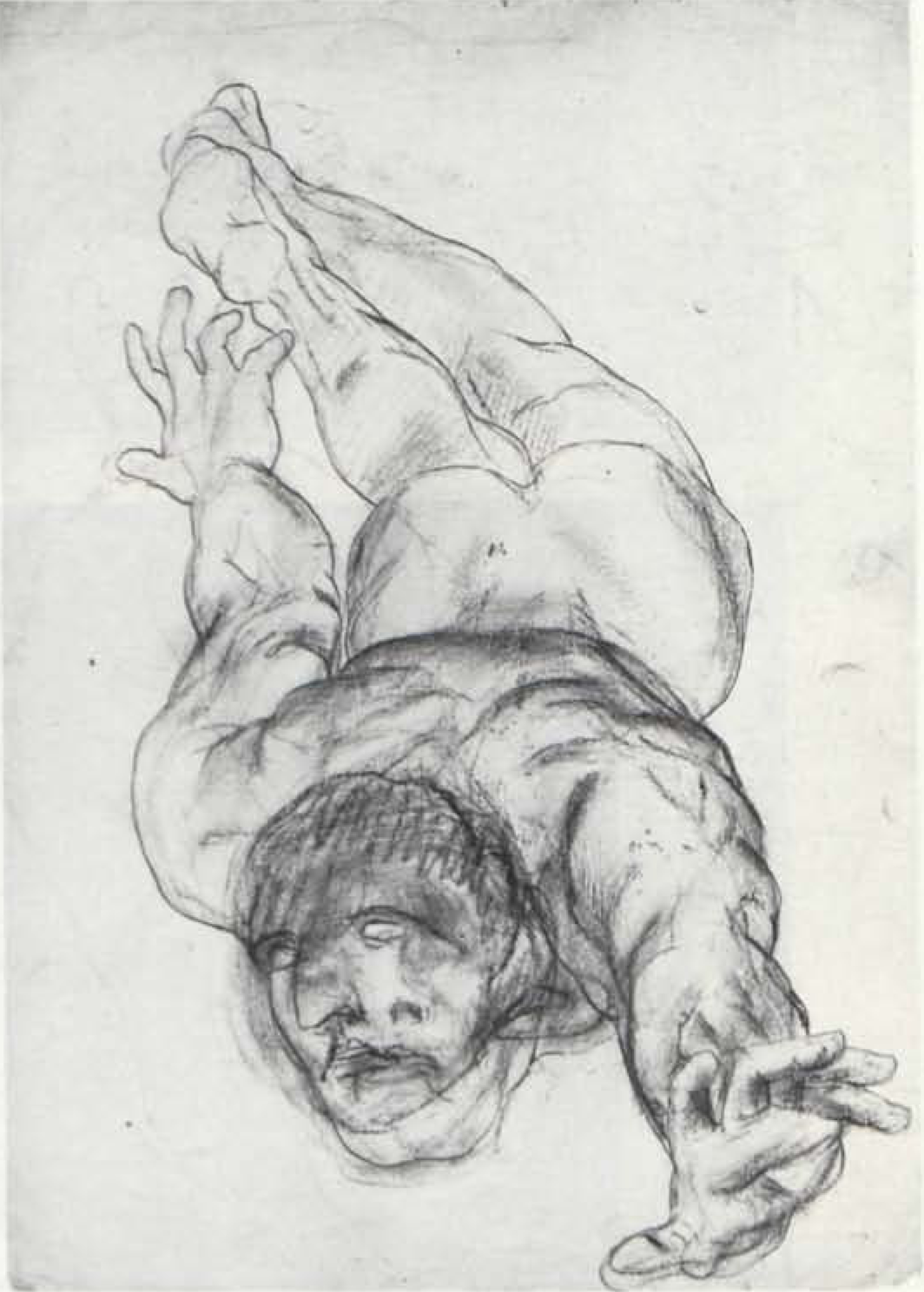

MS 7/27/11. Pencil and ink. 35 × 26 cm. A powerful male nude descending. Cf. The Book of Urizen, plate 14.

MS 7/27/12. Pencil and ink with water color wash. 16 × 9 cm. An upside-down figure falls from the starry sky.

MS 7/27/13. Sepia ink drawing. 11 × 14 cm. A kneeling nude male clasps his head with his right hand and a helmet on the ground with his left.

MS 7/27/14. Etching. 14 × 10 cm. A huge man wearing a cape embraces a skeletal woman while holding a goblet high in his right hand. A leopard stands in the foreground.

MS 7/27/15r. Pencil and ink. A sailor is about to throw a bound man overboard. A woman wearing a crucifix, possibly a nun, looks on.

MS 7/27/15v. A pensive-looking girl in a long dress.

MS 7/27/16. 35 × 25 cm. Two male figures, supine woman, serpent. It isn’t clear whether the standing male is about to stab the fallen one or to rescue him from the serpent.

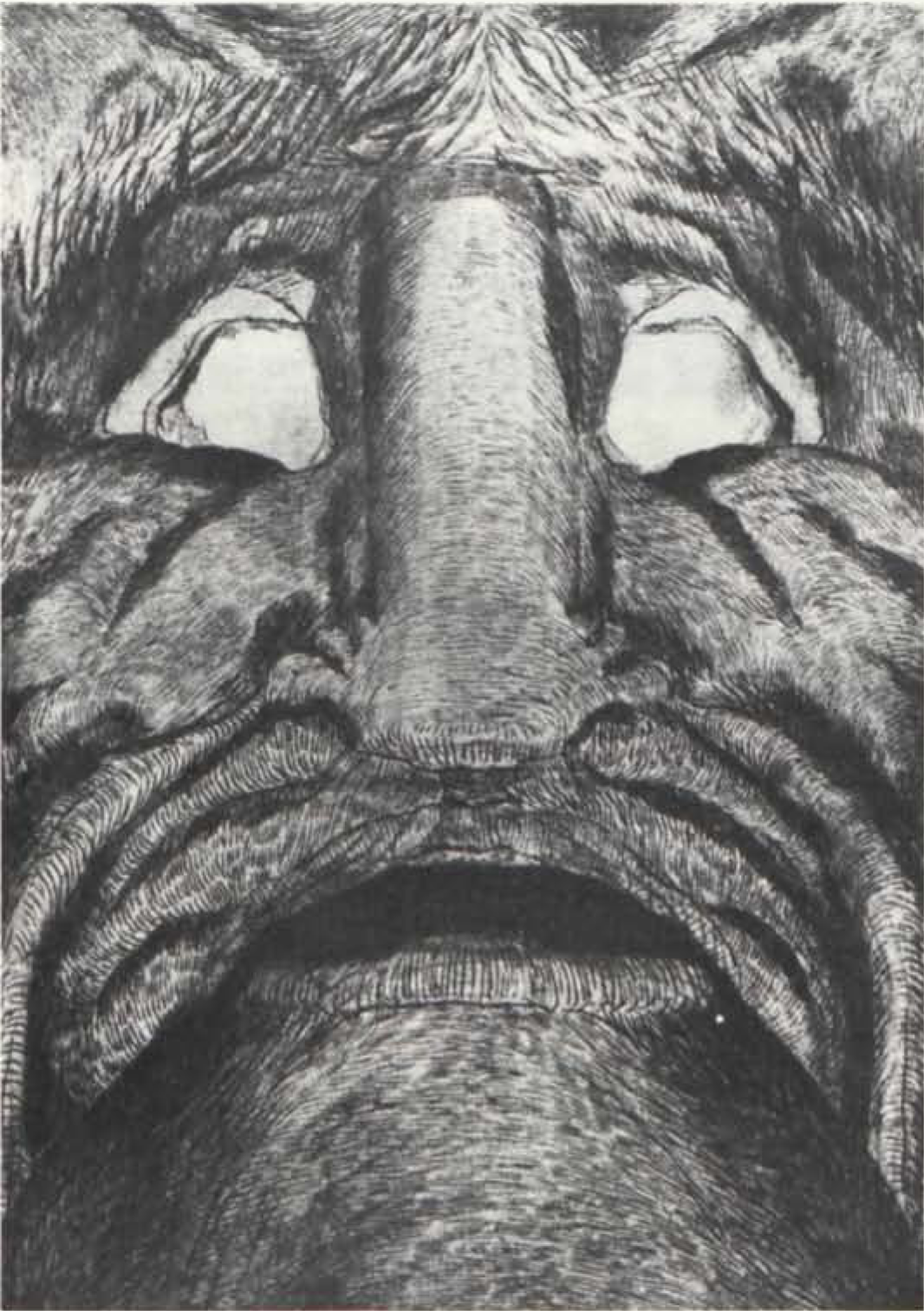

MS 7/27/17r. 20 × 26 cm. Inscribed “Polyphemus watching Galatea.” The bearded, mountain-like Polyphemus stretches his arms imploringly.

MS 7/27/17v. Sketch of a nude woman with her left arm about a child.

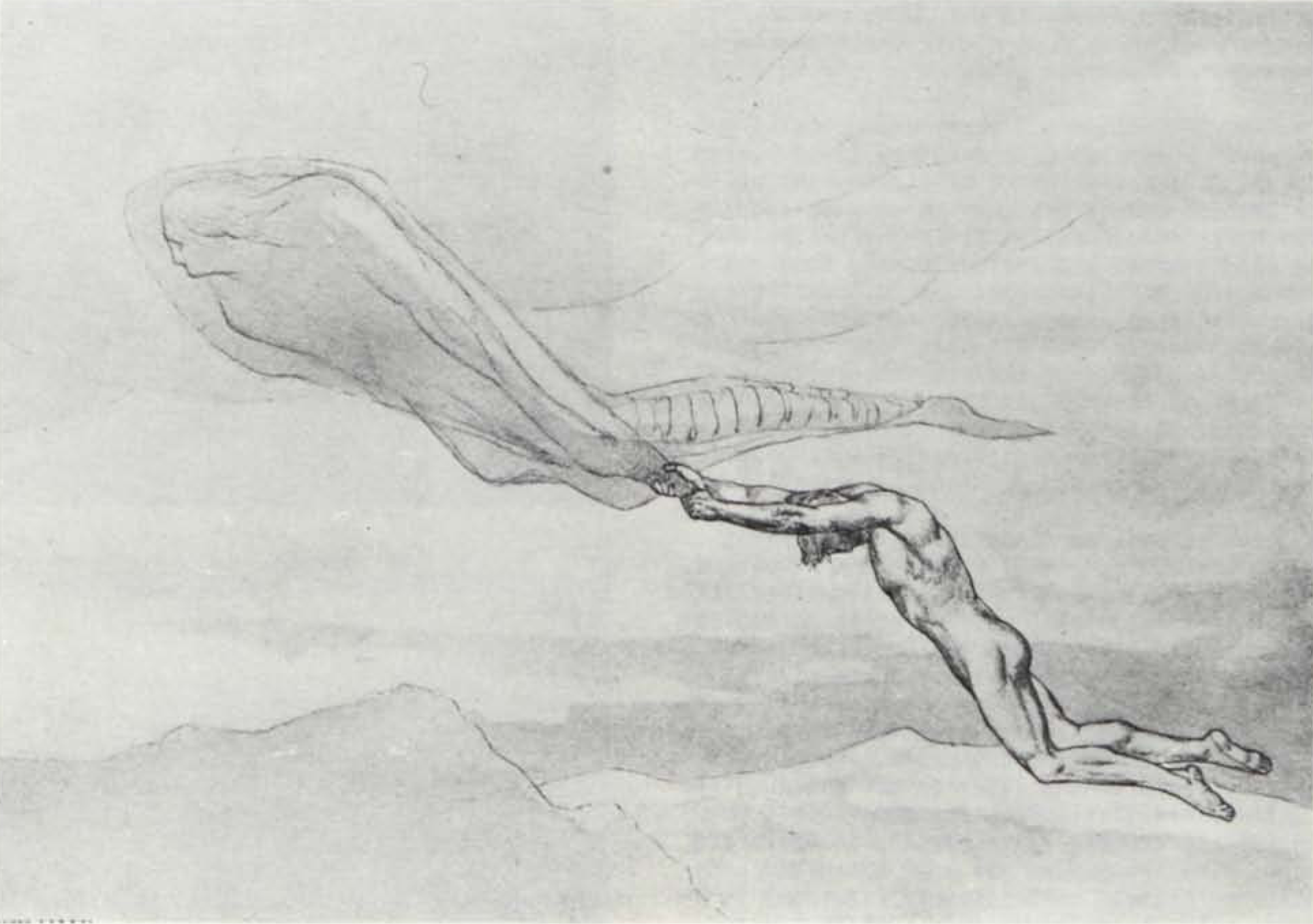

MS 7/27/18. Autotype. Sheet 25 × 32 cm; design area 17 × 24 cm. A naked man is towed through the air by a larval female. This design does not appear in Mrs. Cholmondeley’s Emblems.

MS 7/27/19. Sepia colored autotype reproduction. 23 × 28 cm. Inscribed at the top “Madness” and signed in the lower left hand corner: “Made in the Summer of 1870 / J. T. Nettleship.” Ms. note at the bottom reads as follows:

The prostrate figure symbolizes a man who near the summit of his career has been struck down by madness; hands as of Earth-spirits come out of the ground, lift the circlet from his head, and begin to draw him in, as worms suck in a straw. The male figures behind him (right of the design) symbolize his past acts; they stab themselves. The female figures symbolize the emotions; they wait. The figures behind him, up to the hill top (left of the design) symbolize his future achievements; they throw away crown and stars which were to be his rewards. Every face in the drawing is bowed and hidden, for shame’s sake. x The design embodies the prospective fear, in any sane mind, that madness must mean an annihilation of all individuality, of all the results of past effort or love, and of all future hopes of achievement. But the earth-spirits, while they take the man to themselves, out of sight,, perhaps renew him, but not as the same unity.

x The figure next in front of the prostrate man gives back to the male figure just behind him some pledge that had been given to the future, some unfinished work—useless now. The embodiment of past acts and emotions makes them as it were friends and lovers of the man, identified with his aims.

J. T. Nettleship

22 April 1890x

MS 7/27/20. Autotype. Sheet 25 × 31 cm. ; design area 16 ½ × 24 cm. A sower, following a butterfly, scatters his seed, which is devoured by geese following him. This is identical, save in size, with the much smaller version in Emblems. The same is true of nos. 21 and 22 below. All three lack inscriptions here. In Emblems this one bears the legend “SOWING WILD OATS.”

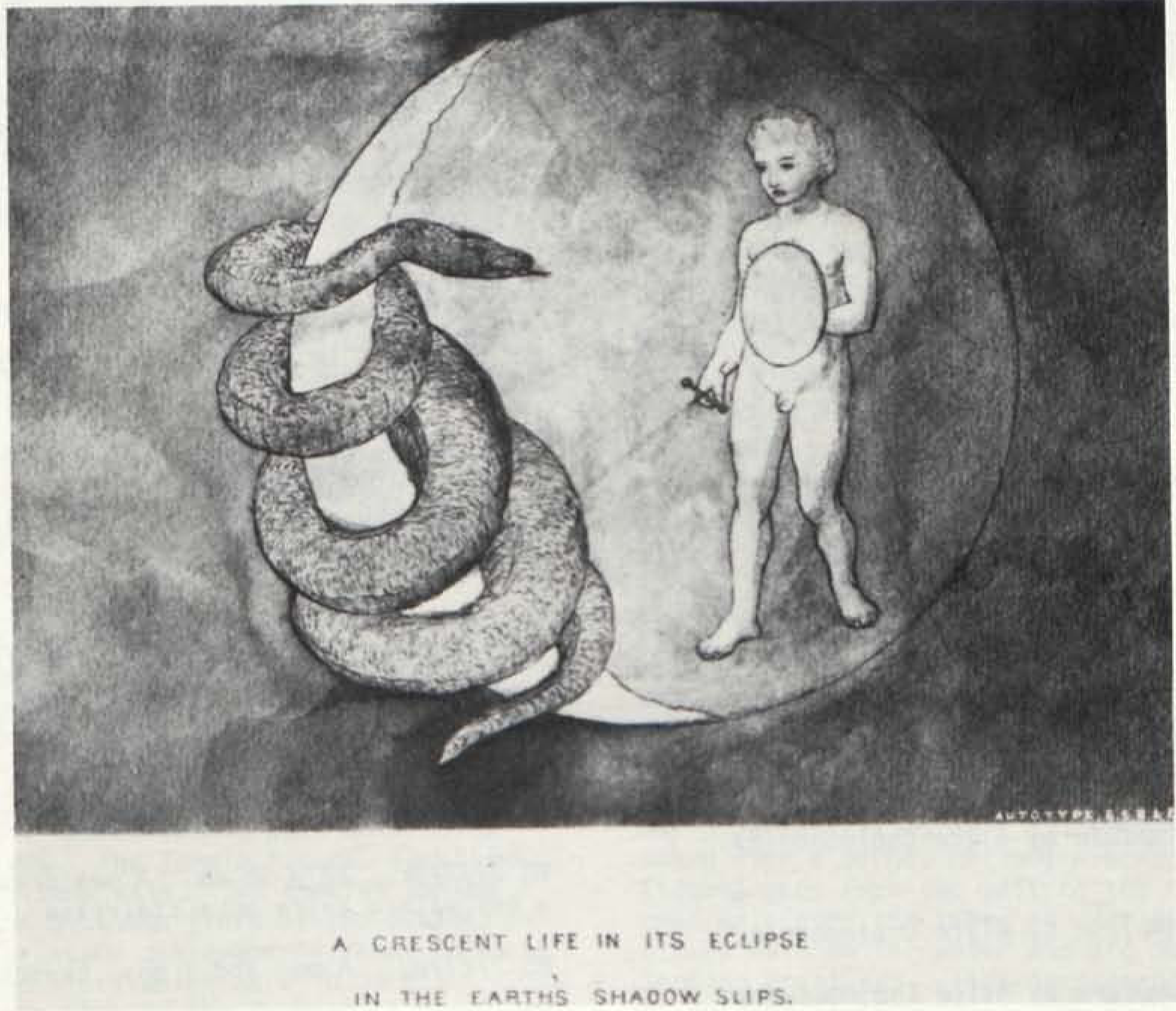

MS 7/27/21. Autotype. Sheet 25 ½ × 33 cm. ; design area 16 ½ × 24 cm. A naked child addresses a serpent with an ear trumpet. The corresponding plate in Emblems bears the printed legend “THE DEAF ADDER—WITH AN EAR TRUMPET.”

MS 7/27/22. Autotype. Sheet size 25 ½ × 31 ½ cm. ; design area 17 × 24 cm. A naked man with a sickle in a rural landscape. Legend in Emblems only: “REAPING WILD OATS.”

MS 7/27/23r. Autotype. Sheet 26 × 32 cm. ; design area 16 ½ × 24 cm. A huge human skeleton and a naked woman in the recess of an overhanging rock. The skeleton points left, and the woman seems about to crawl out in that direction. Not in Emblems.

MS 7/27/23v. Pencil drawing of an almost supine nude woman. Possibly a study for the lower figure in no. 25 below.

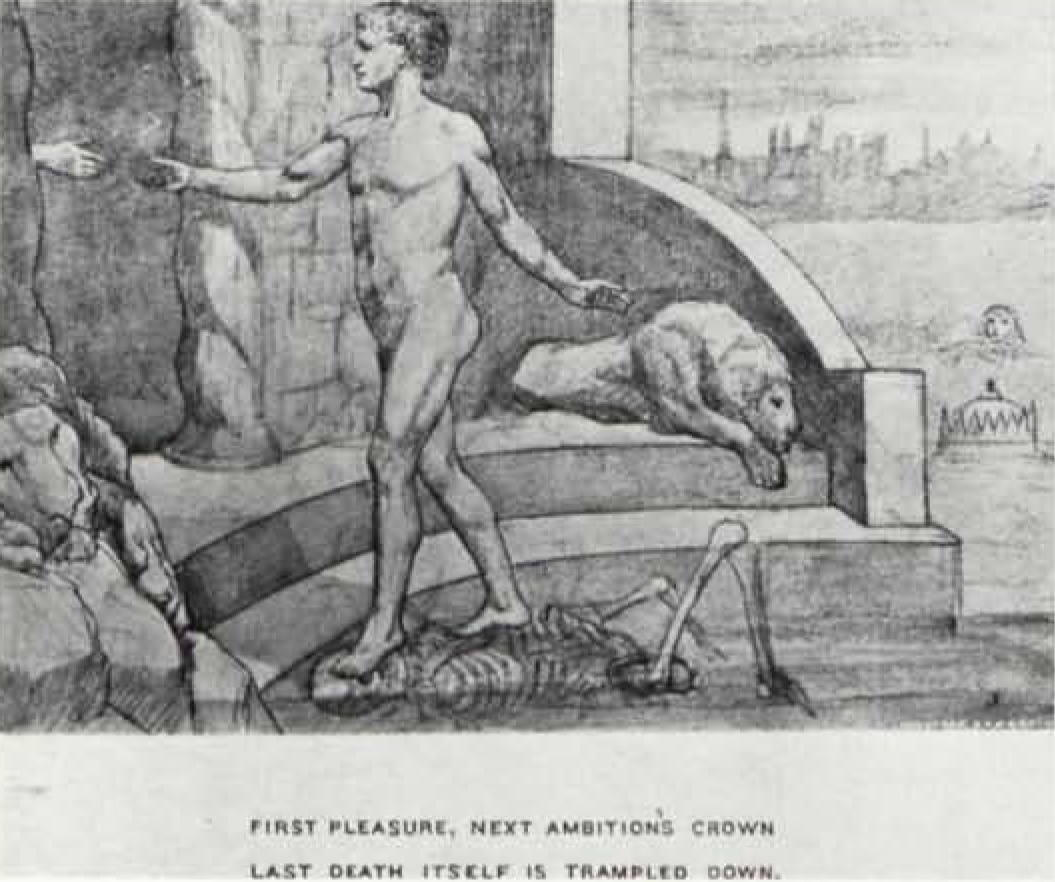

MS 7/27/24. Autotype. 17 × 20 cm. From Emblems, with printed text: “FIRST PLEASURE, NEXT AMBITION’S CROWN / LAST DEATH ITSELF IS TRAMPLED DOWN.” See illus. 7.

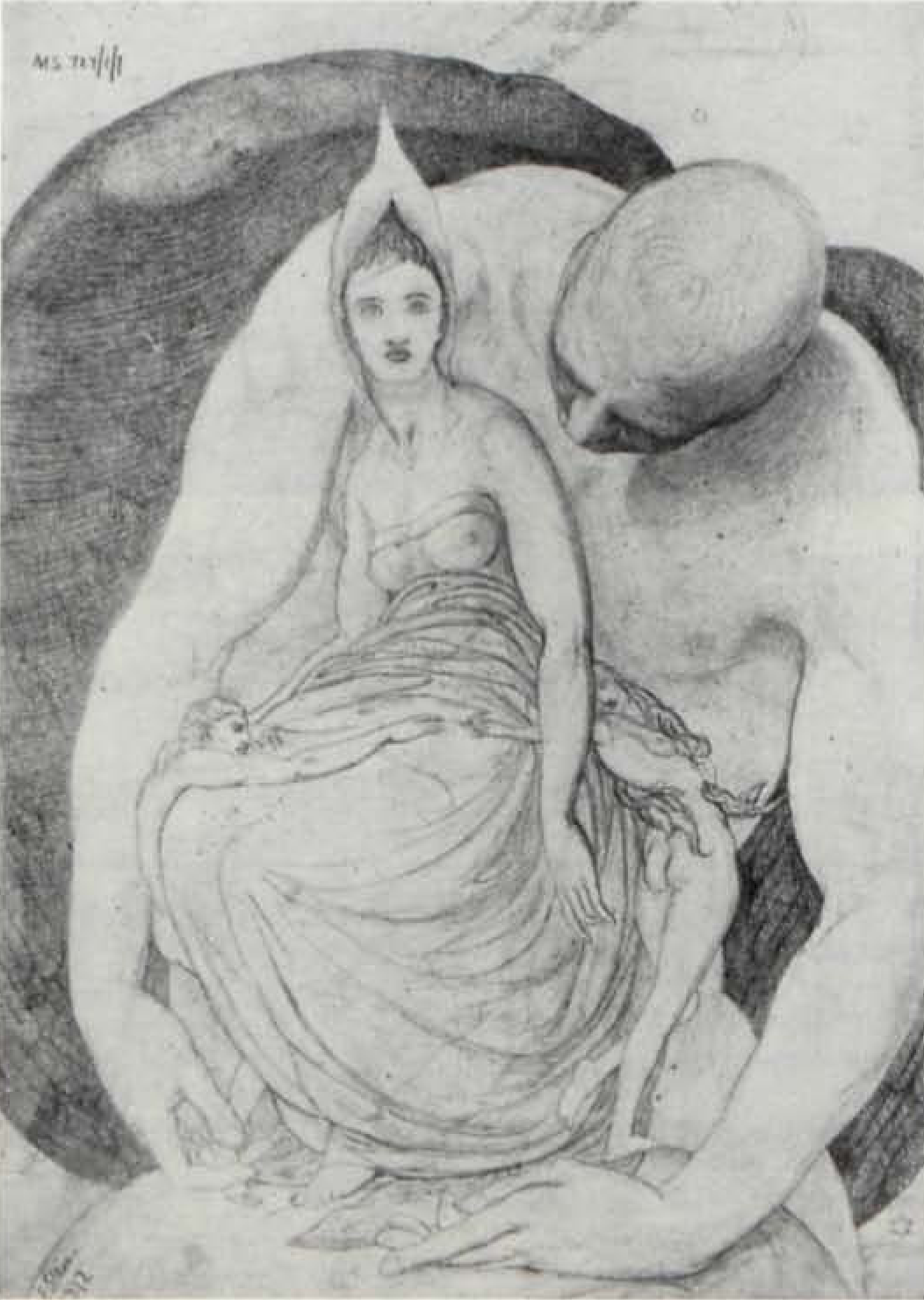

MS 7/27/25 (2 copies). Autotype. Sheet size 31 × 25 cm. ; design area 23 ½ × 16 ½ cm. A male figure descends through the sky to a bound woman. The corresponding, smaller plate in Emblems bears the legend: “A FALLING STAR / THE LOST PLEIAD.”

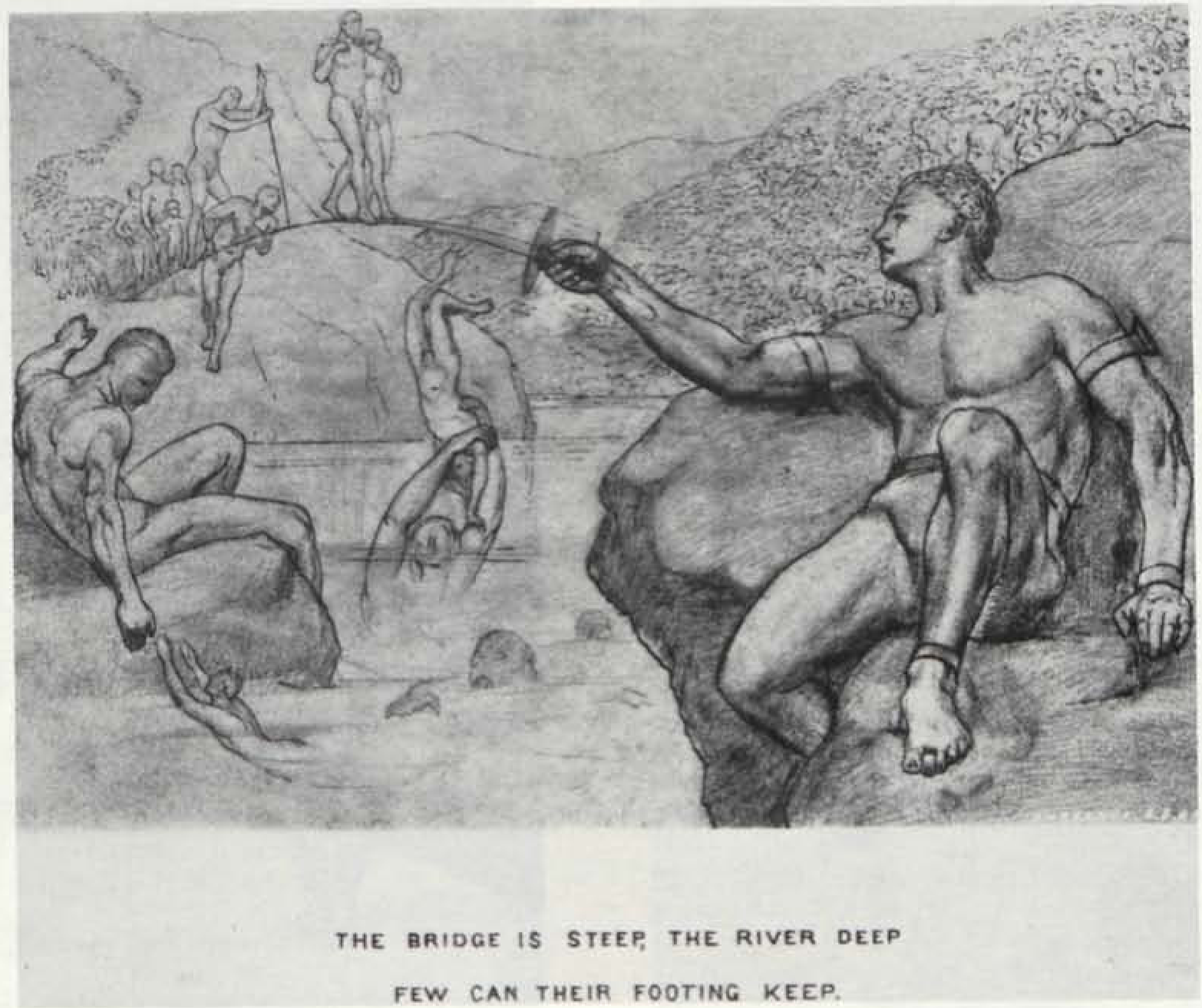

MS 7/27/26. Autotype. Sheet size 25 ½ × 32 cm. ; design area 17 × 24 cm. A naked giant extends a sword over a gorge. A long procession of small figures goes from the left to the center. The first ones walk over the sword as over a bridge, while others swim in the water and are pursued by demonic-looking creatures. The corresponding, smaller plate in Emblems is legended: “THE BRIDGE IS STEEP, THE begin page 194 | ↑ back to top RIVER DEEP / FEW CAN THEIR FOOTING KEEP.”

MS 7/27/27. Photographic reproduction of “God with Eyes Turned Inward Upon His Own Glory.” From Thomas Wright’s Life of Payne. See illus. 1.

APPENDIX II: Emblems by Alice Cholmondeley

-

THE BRIDGE IS STEEP, THE RIVER DEEP / FEW CAN THEIR FOOTING KEEP. See Appendix I, no. 26.

-

FIRST HEAVEN, NEXT AMBITION’S CROWN / LAST DEATH ITSELF IS TRAMPLED DOWN. See Appendix I, no. 24.

-

THE LAMP OF TRUTH. The lamp is phallic.

-

A FALLING STAR / THE LOST PLEIAD. See Appendix I, no. 25.

-

LA CRUCHE CASSÉE. THE PITCHER THAT WENT TO THE WELL TOO OFTEN. A Rossetti-ish lady and Landseer-ish lions.

-

THE LOST WAY, ALL ASTRAY / THE SPHINX AS GUIDE. A male nude lacking the energy of his Blakean counterparts. A doggie-like, leashed sphinx, rather ludicrous than enigmatic.

-

SOWING WILD OATS. See Appendix I, no. 20.

-

REAPING WILD OATS. The grotesque figure with his sickle may owe something to Despair with his flaying knife in Blake’s The House of Death. See Appendix I, no. 22.

-

THE DEAF ADDER—WITH AN EAR TRUMPET. See Appendix I, no. 21.

-

No text. Two billing swans and their reflections.

-

L’ANIMA IN MASCHERA. / MISREPRESENTED. The death-like figure with the scythe is conventional, but the lightly draped lady on her swan-throne seems distinctive of Nettleship, as does the artist who paints her.

-

A CRESCENT LIFE IN ITS ECLIPSE / IN THE EARTH’S SHADOW SLIPS. Serpent and crescent moon—cf. Blake’s “Narcissa” engraving for Young’s Night Thoughts.

-

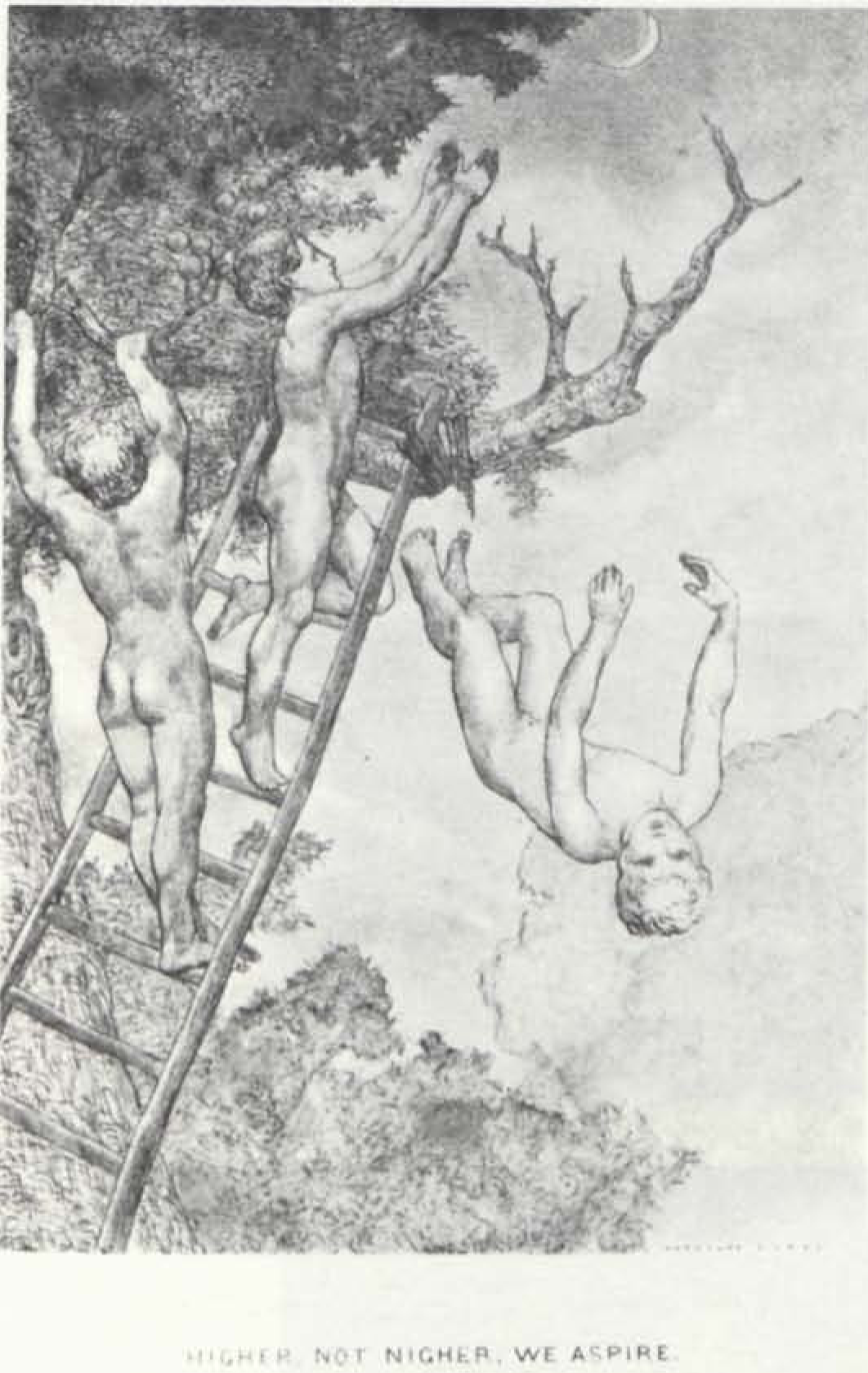

HIGHER, NOT NIGHER, WE ASPIRE. A literalized version of “I want I want” in Blake’s Gates of Paradise.

-

PLUCKING DAISIES (FROM GOETHE’S “FAUST”) / “ER LIEBT MICH—ER LIEBT MICH NICHT.” A nude woman holds a daisy on a country road.

-

No text. A diminutive, naked child leaps from a frying pan (held by a girl) into the fire.

-

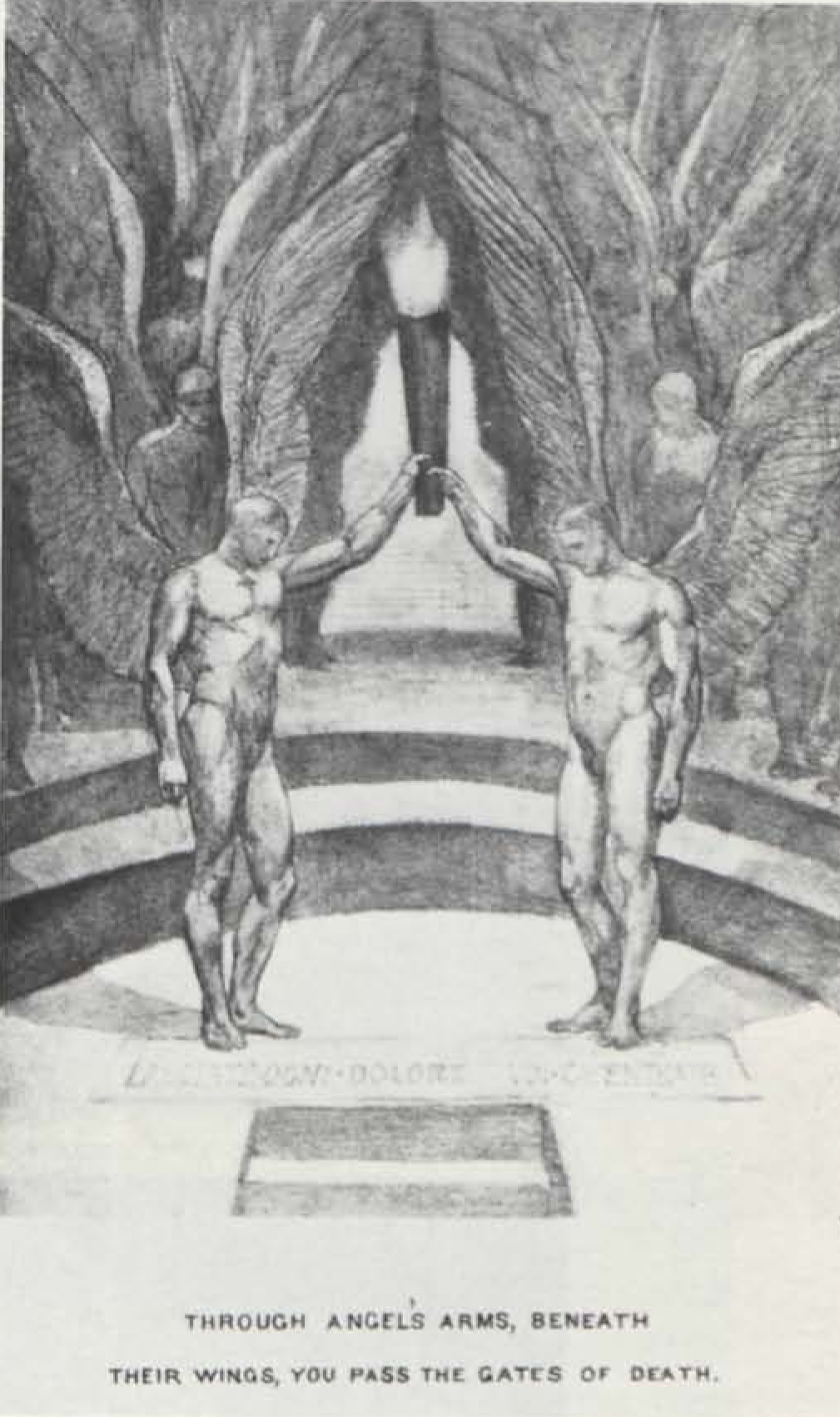

THROUGH ANGEL’S ARMS, BENEATH / THEIR WINGS, YOU PASS THE GATES OF DEATH. The joining of the angels’ wings to form a Gothic arch which is a passageway to death makes a link to Blake probable.

-

A FAREWELL. A lady’s hand waves a handkerchief to a departing horseman.