article

begin page 64 | ↑ back to topBLAKE’S TRANSFORMATIONS OF EZEKIEL’S CHERUBIM VISION IN JERUSALEM

During the only period he lived away from London, Blake underwent what he describes in a letter-poem to his friend Thomas Butts as nothing less than a personal Last Judgment, a harrowing experience which involved a crisis of faith in himself and his friends, as well as an accusation by the spectres of “Poverty, Envy, old age & Fear.” These demons hounded him until he found the strength to resist and defeat them in what he calls a “fourfold vision” (E693/K818).1↤ 1 All textual references are to E: The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1970), and to K: Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1966). For a fuller discussion of this letter-poem and its relation to Ezekiel, see Randel Helms, “Blake at Felpham: A Study in the Psychology of Vision,” Literature and Psychology, 22 (1972), 57-66. Jean Hagstrum places this experience in the broader context of Blake’s life, “‘The Wrath of the Lamb’: A Study of William Blake’s Conversions,” in From Sensibility to Romanticism, ed. Frederick W. Hilles and Harold Bloom (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1965), pp. 321-26.

Blake’s allusion to Ezekiel’s vision, which sparked a sudden, liberating personal vision of poetic and prophetic power, marks a turning point in his life. Having abandoned his heroic efforts to forge the “torments of Love & Jealousy” into The Four Zoas, Blake gained the necessary strength to endure the pressure of maintaining artistic faith and integrity in face of William Hayley’s destructive patronage and to persist in the epic tasks of Milton and Jerusalem. This vision awakens him, he says, from his “three years Slumber on the banks of the Ocean” at Felpham (E697/K823), and he adopts a new stance. “If all the World should set their faces against” his work, he declares, “I have Orders to set my face like a flint (Ezekiel iiiC, 9v) against their faces, & my forehead against their foreheads” (6 July 1803; K825). Like Ezekiel on the banks of the Chebar, Blake experiences a personal, as well as political “call” to “Spiritual Acts” of perception and creation.

From this time on Blake’s life and art are informed by Ezekiel’s vision of the Cherubim—the four “living creatures” come out of the whirlwind of cloud and “fire infolding itself,” having the “likeness of a man” (Ezek. 1, 10). Less than a year after Blake returned to London in 1804 he rendered this vision in a watercolor for Butts, “Ezekiel’s Wheels” (illus. 1), which features the human fourfold man, his hand raised in a sign of peace above the wheels whirling in flames. The awakened sleeper, Ezekiel himself, is depicted at the bottom of the picture, lying on a rock beside the river. In the same year Blake painted St. John’s metamorphosis of this vision, “The Four and Twenty Elders casting their Crowns before the Divine Throne” (Rev. 4).2↤ 2 “Ezekiel’s Wheels” is also known as “Ezekiel’s Vision of the Whirlwind.” The change in Blake’s life recorded in his letter-poem is also registered by the contrast between this painting of the wheels and his earlier depiction of Ezekiel’s wheels in an illustration to the ninth night of Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (c. 1795), repro. by Geoffrey Keynes in Illustrations to Young’s Night Thoughts (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1927), no. 28, p. 56, as mathematic mysteries intimidating a benighted worshipper on the shores of the sea of chaos, a far cry from the expectant, ecstatic visionary of the later picture. “The Four and Twenty Elders” is repro. by Darrell Figgis in The Paintings of William Blake (London: E. Benn, 1925), pl. 4. Blake’s insistence on the human form of the Cherubim, his emphasis on its hand, fire and wheels, and his attention to the sleeper’s landscape of rock and river become central to Jerusalem, also begun in this year.

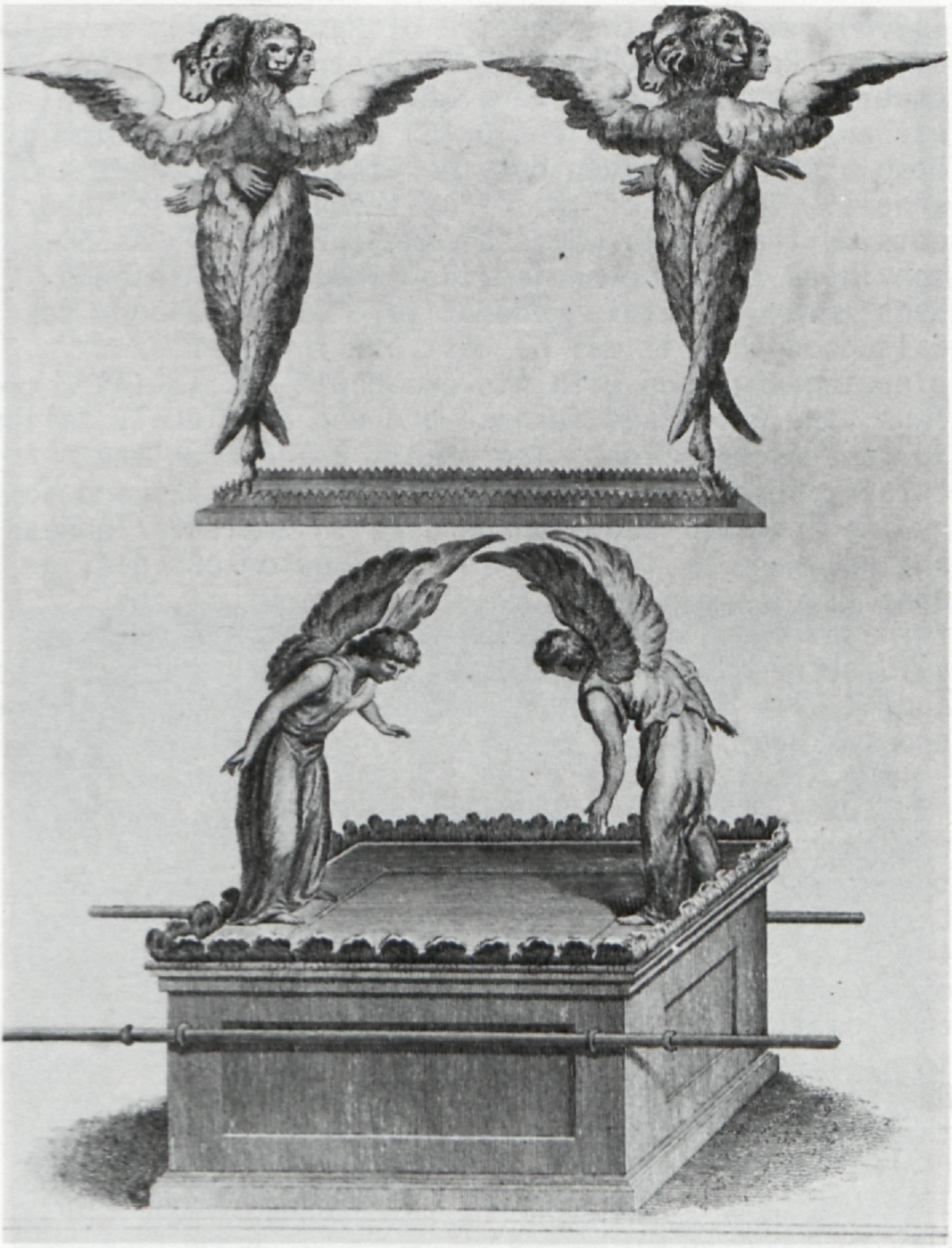

Blake explicitly identifies Ezekiel’s Cherubim, his idiosyncratic Hebrew spelling in the margin of Plate 32 of Milton alluding to the identification of the Cherubim and humanity, with aesthetic and moral wholeness, the “Human Form Divine” and “holy Brotherhood” (E130/K521).3↤ 3 On Blake’s Hebrew spelling see Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems (London: Penguin, 1977), p. 981. All graphic references are to IB: The Illuminated Blake, ed. and anno. David V. Erdman (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1974). Having seen this vision, he proclaims to the public in his Descriptive Catalogue that it contains the archetypes of all true art, “those wonderful originals called in the Sacred Scriptures the Cherubim” (E522/K565). Blake refers begin page 65 | ↑ back to top here specifically to graphic works, but the culmination of his seizing on the vision of the human, bodily form of the Cherubim as the original of all truly imaginative art, verbal and graphic, occurs in the last plates of Jerusalem. Here the “Four Living Creatures” (98:24, 42) frame a celebration of resurrection in which everything—animal, vegetable, mineral—becomes individuated living being that appears united in the “One Man” (98:39) of Ezekiel’s vision. Furthermore, Blake makes it clear that these “Visionary forms dramatic” (98:28) or Cherubim is the “exemplar” (98:30) of all true art, including his own prophecy—Jerusalem. This is why, when Blake in a later work, The Laocoön, condemns classical art for being mere “mathematical diagrams” as opposed to the “Naked Beauty displayed” of prophetic art, he further and more damningly accuses it of being a debased copy of the “Cherubim of Solomon’s Temple” (E270/K775-76) reflected in Ezekiel’s vision.

As Ezekiel’s Cherubim vision became the paradigm in Blake’s mind not only for the clarity and unity of vision but for the shape and method of his epic prophecy, its demonic parody in the form of Ezekiel’s “Covering Cherub” also became important.4↤ 4 That Blake understands the Covering Cherub as the demonic parody of Ezekiel’s Cherubim is evident in his painting of him as a winged being, surrounded by flames, who, posed in a similar attitude to the figure in “Ezekiel’s Wheels,” makes the same gesture as the fourfold man. In this picture of the Covering Cherub, commonly known as “Satan in His Original Glory” (repro. in Figgis, pl. 8; Geoffrey Keynes, Blake’s Bible Illustrations [Paris: Trianon Press, 1957], pl. 82), which contemptuously alludes to the classical winged “Victory” (Andrew Wilton, “Blake and the Antique,” The Classical Tradition, British Museum Yearbook 1 [London: British Museum Publications, 1976], p. 198), the visionary eyes of the spirit-filled wheels are changed to fallen stars, dying remants of the zodiacal wheel of fate. The body’s fragmentation is symbolized by the small, faceless, contracted beings hunched in fear and confusion or hurtling downward, as in depictions of the Last Judgment. Ezekiel vows to destroy the tyrannous “Cherub” appearing, like the Cherubim itself, as a man “midst of the stones of fire” (Ezek. 28. 16). This satanic being is in Jerusalem the “Selfhood” and the Spectre of self-doubt, the destroyer of brotherhood and prophetic faith masquerading as the true Cherubim (89: 10; 96:8). As the Cherubim is perverted by false artists, such as the Greeks, it becomes a parody of itself, the Covering Cherub, who is exceedingly dangerous because it is so easily mistaken for the true Cherubim. Blake is acutely aware, after his experience at Felpham, that the imposter pretending to friendship is more dangerous than the outright antagonist, as he makes clear in a couplet privately addressed to Hayley, asking him to be an “Enemy for Friendships sake” (E498/K545). The Covering Cherub conceals the very truth that it parodies, for imaginative liberty—Jerusalem herself—is hidden within “as in a Tabernacle of threefold workmanship, in allegoric delusion & woe” (89:44). When the outer garment or false body of self-delusion is thrown off, like the graveclothes of Jesus, the true Cherubim body is revealed. Until this comes to pass at the end of the poem, however, the threefold Covering Cherub mocks the fourfold Cherubim.

This equivocal opposition is rooted in Blake’s interpretation of an ambiguity in Genesis: God, after driving man out, placed Cherubim “at the east of the garden of Eden” and a “flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life” (Gen. 3.24).5↤ 5 Blake’s identification of the Cherubim here with the fourfold creatures of Ezekiel and John is clear from his Genesis “Title Page” (repro. in S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary [New York: Dutton, 1971], illus. II) and his ninth illustration to Paradise Lost (repro. Figgis, pl. 22), “The Expulsion from Eden” (1808), which pictures at its top four full-faced horsemen and horses, foreshadowing the end of Jerusalem: “every Man stood fourfold. each Four Faces had. / . . . the Horses Fourfold” (98:12-13). Does “keep the way” mean that the Cherubim at the gate bars man from the tree of life or preserve it for him? Blake provides the answer in an early work, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, saying: “For the cherub with his flaming sword is hereby commanded to leave his guard at tree of life, and when he does, the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite. and holy” (E38/K154). Blake asserts that the Cherubim must abandon its traditional role as guard if art and the true prophet-poet are to triumph.6↤ 6 Christian orthodoxy, of course, interprets the Cherubim in Eden as a guard keeping man out, but Blake was not alone in his heterodox position. John Parkhurst, a Hebrew scholar and contemporary of Blake’s comments in his widely respected An Hebrew and English Lexicon, . . . 4th ed. (London: for G. G. and J. Robinson, 1799), that the Cherubim was “undoubtedly” placed at the gate of Eden “not to hinder, but to enable man, to pass through it” (p. 343). This book may have prompted Blake’s renewed interest in the ambiguous Genesis passage, for when Blake was studying Hebrew at Felpham (E696/K821) he undoubtedly used this text, as it was the best known of its time, and William Hayley owned the fourth edition (A. N. L. Munby, ed., Sale Catalogues of Libraries of Eminent Persons [London: Mansell, 1971], II, 136). The Cherubim who assumes the role of guard becomes a parody of itself, a perverse imposter barring man from the Garden of Eden, Blake’s primary symbol for the world of imagination. This perversion is the Covering Cherub, whom Ezekiel also places in Eden (Ezek. 28. 13), a nightmare of “Doubt which is Self contradiction” that in the Gates of Paradise flies around Blake as a “Flaming Sword” (E265/K770). As the accuser, Satan, the Cherubim in its fallen state becomes the Covering Cherub responsible for expelling man from the imaginative world and preventing his return by instilling doubt in himself and his brothers. As the archetype of prophetic art, however, the Cherubim or “One Man,” whom Blake identifies in Milton (42:11) with Jesus, guides man into Eden, where self-delusion is removed and all appears “infinite.”

In Jerusalem the ambivalence of the Cherubim as guard or guide is central. Blake recounts a vision in the proem to Chapter 4 (E230-31/K717-18) of a “devouring sword turning every way” and Jesus striving “Against the current of this Wheel.” Jesus is called the “bright Preacher of Life,” who wields the sword of the prophetic word in opposition to the “dark Preacher of Death.” The “devouring sword” of death is another name for Blake’s “Covering Cherub.” Jacob Boehme, whose interpretation of Genesis influenced Blake, calls this the sword “proceeding from Babel,” that is, the false word.7↤ 7 Quoted by Kathleen Raine, Blake and Tradition (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1968), I, 329. Raine specifies Blake’s debt to Boehme on this point in her commentary to the proem, I, 330-32. Blake’s vision opening Chapter 4 is of Jesus’s attempt, in Boehme’s language, to change “the Fire-sword of the Angel into a Love-sword, . . . And this is the true Cherub which drove the false Adam out of Paradise, and brings him in again by Christ.”8↤ 8 Jacob Behmen [Boehme], The Mysterium Magnum; Or an Explanation of . . . Genesis (London: for G. Robinson, 1772), Vol. III of The Works . . . with Figures by . . . William Law (London: for M. Richardson, 1764-81), p. 116; italics his. The true Cherubim, who ushers us into imaginative realms, is Jesus, the true Word.9↤ 9 Parkhurst shares this view, p. 341. He is the “One Man” in whose body at the end of Jerusalem the Living Creatures or “Visionary forms dramatic” of the Cherubim have their unity.

We are invited to view Blake’s prophecy, then, as an attempt to turn the fire-sword into a love-sword, just as in the first chapter of the poem Los (Blake himself) attempts to turn Hand’s (Los’s Spectre) fiery sword into a “Spiritual Sword” (9:5, 18). In the prose introduction to Chapter 3, Blake calls this the war between the “Natural Sword” and the “Spiritual” sword (E198/K682), which he makes clear is between experiment based on doubt and revelation based on faith, self-righteousness and love, tyranny and liberty, as well as the classical warrior ideal and the command of the prophet Jesus to “Conquer by Forgiveness.” In short, by separating the true from the false Cherub, changing the guard to a guide, Blake attempts in his prophecy to usher us into Eden and its Tree of Life, that personal and political liberty grounded in the freedom of the human imagination.

Blake guides us into the world of imaginative liberty in Jerusalem by a non-traditional meditation on the Cherubim appearing to Ezekiel, that “glorious vision,” as Ecclesiasticus puts it, “which was shewed him upon the chariot of the Cherubims” (Eccles. 49.8). Blake, knowing this text, as well as Revelation 4, was well aware that Ezekiel’s vision was understood to be, as meditated upon by the Jews, primarily a chariot-vision and was, as Austin Farrer points out, “a technique of ecstasy.” This tradition of God descending from the heavens begin page 66 | ↑ back to top in his fiery chariot, which catches the worthy meditator up in spiritual ecstasy, preserved in the books of the Merkabah mystics, came to be one of the two pillars of the Kabbalah.10↤ 10 Austin Farrer, A Rebirth of Images; the Making of St. John’s Apocalypse (1949; rpt. Boston: Beacon, 1963), p. 262. On Blake’s knowledge and use of the Kabbalah, see S. Foster Damon, William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1958), p. 446; Denis Saurat, Blake and Modern Thought (London: Constable, 1929), p. 102; Milton O. Percival, William Blake’s Circle of Destiny (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1938), p. 82; Désirée Hirst, Hidden Riches (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1964), p. 156; and Asloob Ahmad Ansari, “Blake and the Kabbalah,” in William Blake: Essays for S. Foster Damon, ed. Alvin H. Rosenfeld (Providence, R. I.: Brown Univ. Press, 1969). After completing Jerusalem (c. 1820), Blake discovered another version of the chariot vision as ecstatic ascent in chap. 14 of the Book of Enoch, trans. Richard Laurence (London: Oxford, 1821). He does not include this, however, in a series of drawings illustrating the book (repro. Blake Newsletter 28, 7 [Spring 1974], 83-86). Blake was not concerned, however, with ecstatic ascent but with assertion of the prophetic imagination in times of spiritual and political oppression. His purpose was to unleash Christ on Antichrist, the true against the false word, as in his Ever lasting Gospel, where he says Jesus “Became a Chariot of fire / . . . cursd the Scribe & Pharisee / . . . Broke down from every Chain & Bar / And Satan in his Spiritual War” (E515/K749). Blake departs from the traditional, mystical meditation on the Cherubim vision by making the benignly descending chariot of convention a war-chariot instead. This departure owes much to the version of Ezekiel’s vision in Paradise Lost (VI: 749-59), but Blake also changes Milton’s static, patriarchal chariot by identifying it with the dynamic, fiery prophet Jesus. Traditional Cherubim meditation emphasized watching and waiting for its appearance, clearly distinguishing God the rider from his chariot, whereas Blake emphasizes actively uniting with the chariot.

Blake’s meditative technique, like that of Jesus, who “became” the Chariot, achieves the unity of chariot and rider, image of the true relation of the prophetic poem to its poet, as well as its audience. He expresses this unity in “Ezekiel’s Wheels” by putting the human visage of Christ, who “rides” at the top of the picture, in each of the faces which carry him on the wheels below. This living body of the Cherubim vision corresponds to the prophetic word of Jerusalem (98:28-40). Consequently, Blake’s prophecy is not a vehicle for vision, a means of attaining the mystical end of spiritual transport, but the body of the Word itself in its most disturbing fullness. Blake, as rider, is one with the chariot of his poem (98:40-42). That is, by a series of transformations of the chariot-vision, he internalizes or accepts as his own its images of forgiveness, thereby entering the Cherubim body and freeing himself from guilt and doubt. By this act he reveals the Covering Cherub as false, casting out “Satan this Body of Doubt that Seems but Is Not” (93:20).

Furthermore, he expects his audience to do the same, to make “companions” of these images, which heal a fragmented psyche and society by liberation from self-doubt and mutual suspicion. Thus he entreats his reader to actively enter his work in A Vision of the Last Judgment: “If the Spectator could Enter into these Images in his Imagination approaching them on the Fiery Chariot of his Contemplative Thought if he could . . . make a Friend & Companion of one of these Images of wonder . . . then would he arise from the Grave then would he meet the Lord in the Air & then he would be happy” (E550/K611). He would meet Jesus because he would be part of the chariot-body of Jerusalem, one with Blake’s visionary forms. The Merkabah is a “giant image,” as Harold Bloom rightly observes, “for the prophetic state-of-being, for the activity of prophecy.” But because Blake expects his audience to join him as rider in becoming one with the chariot, Bloom is mistaken in his notion that throughout Jerusalem Blake “studies in hope to see” the Merkabah.11↤ 11 Harold Bloom, “Blake’s Jerusalem: The Bard of Sensibility and the Form of Prophecy,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 4 (Fall 1970), 15, 10; italics his. This is the hope of the mystic not of the radical engraver on South Molton street in London. Blake insists that we “Enter” into his images and that we remember he was first called by Ezekiel’s vision to speak out against mental and physical tyranny by transforming and embodying that archetypal vision of wholeness and brotherhood in works of art.

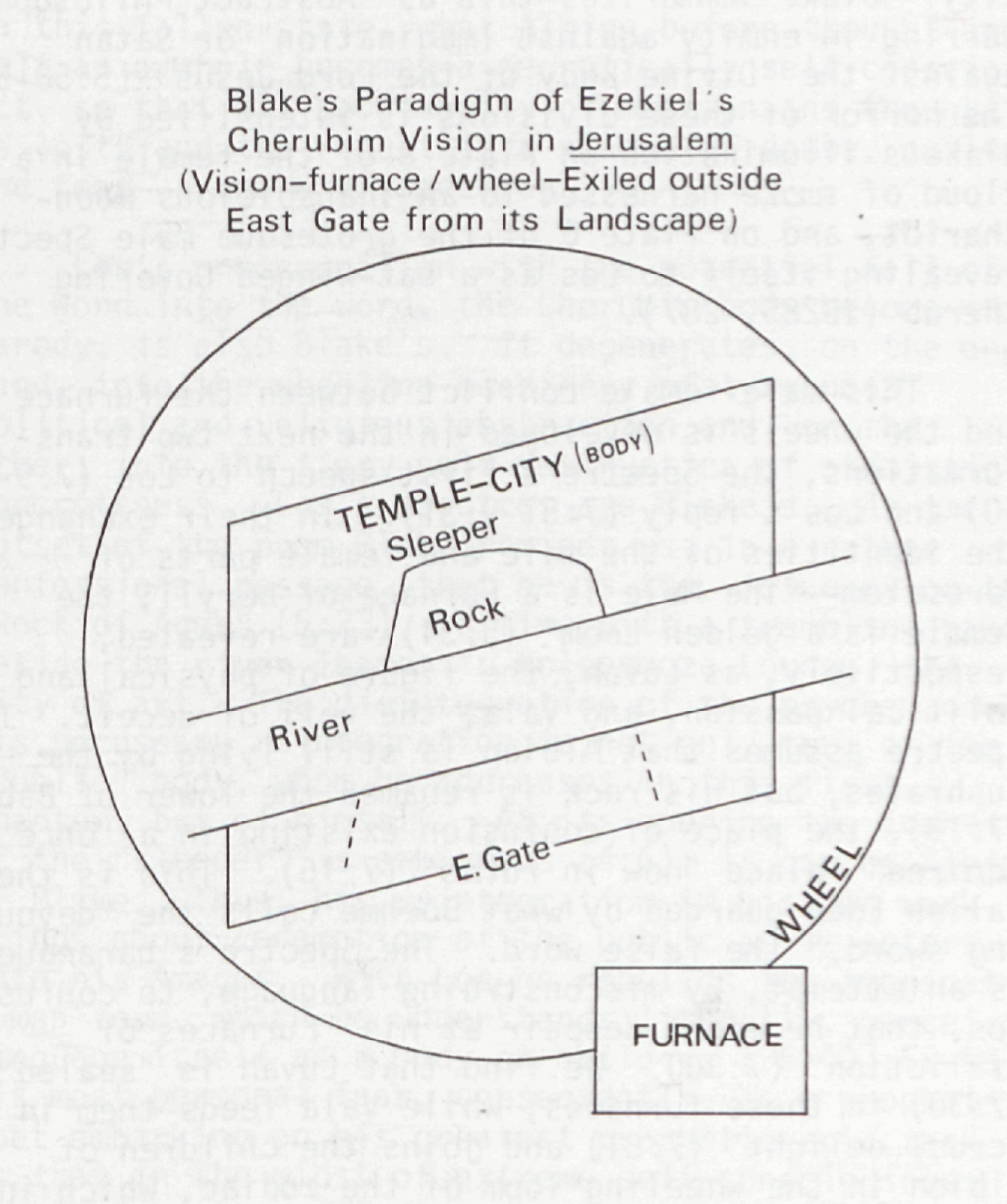

Departing from the tradition of the Cherubim meditations in Revelation, the Kabbalah and Paradise Lost, Blake replaces God as rider with the visionary himself, Jesus-Blake, and thus effects the union of rider and chariot. That is, he insists on the unity of imaginative vision—the chariot—and its landscape—ultimately the mind and body of the prophet. Blake employs Ezekiel’s chariot-vision of “wheels within wheels” (Ezek. 1.16) and “burning coals of fire” (1. 13) or furnace as an image of man’s imaginative part. For Blake, the “spirit of the living creature” in the wheels (Ezek. 1.20) is man’s imagination, as is the furnace, which he associates with Jesus. The furnace in Daniel is a threefold fiery death for the three faithful sons of Israel until Jesus, by his saving appearance as the “son of God,” makes it fourfold (Dan. 3.25; cf. E533/K578). The scene or natural landscape in which the prophet lies is, on the other hand, an image of the body alienated from itself. It is a projection and externalization of the imaginative body until, “all Ridicule & Deformity” (E677/K793), it mocks the prophet and becomes in Jerusalem the threatening “serpent” nature (43[29]: 80). Blake adds the obdurate rock, symbol of contracted vision, to the natural landscape in Ezekiel, but otherwise conflates the landscape of its first and tenth chapters, respectively, where the visionary lies beside a river and stands in the court of a temple-city. Developing John’s use of Ezekiel in Revelation, Blake adopts his metaphoric identification of temple, city and bride (Rev. 3.12; 21.2, 10-27), one confirmed by St. Paul’s trope of the temple-body (I Cor. 6.19) and by the appearance of the Cherubim in the “likeness of a man” (Ezek. 1. 5). Its appearance of wholeness is the unity of the body and imagination, rider and chariot, in the “One Man.” Man’s fragmented state is a result, therefore, of the separation of imaginative vision from the landscape of his body. In this fallen condition, the furnace and the wheels of the chariot-vision are exiled outside the landscape of the temple-city (E146/K623; Ezek. 10.19) in which the sleeper or potential prophet lies on a rock beside a river (illus. 2), just as Adam and Eve are exiled outside the East gate of Eden.

By a series of meditative transformations, then, Blake brings the exiled chariot-vision back inside its landscape of the rider-visionary, thereby restoring man to psychic and bodily wholeness. In Blake’s symbolism, that is, the furnace and wheels are recalled to the temple-city. And in this he follows the progression from Ezekiel 1, where the Cherubim appears outside the temple, to Ezekiel 10, where the Cherubim appears inside. The drama of the begin page 67 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Before examining Blake’s transformations of Ezekiel’s vision, we must view them within the context of his larger debt to Ezekiel. Addressing the “Public” at the opening of Jerusalem, he repeats a phrase from his letter to Butts, saying, “After my three years slumber on the banks of the Ocean, I again display my Giant forms” (E143/K620). The allusion here to Ezekiel’s slumber by the river Chebar is clear, and Blake reinforces it in his subsequent reference to himself as a “true Orator” (E144/K621), a term Bishop Robert Lowth invokes from Milton to describe Ezekiel, who “frequently appears more the orator than the poet.”12↤ 12 Robert Lowth, Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews (London: J. Johnson, 1787), II, 61. Milton uses the phrase in his preface, “The Verse,” to Paradise Lost. Jerusalem is fundamentally a series of orations aimed at different audiences—the general public, Jews, Deists, and Christians. Consequently, its gross structure is rhetorical; we are confronted with four addresses, saying much the same thing but adapted by varied emphases to their respective readers. Like the gospels it tells virtually the same story four times. Unlike the gospels, however, Blake is not concerned to narrate the life of Jesus but to anatomize the “Temple of his Mind.” Like the books of Ezekiel and Revelation, the basic question of Jerusalem is who shall have dominion, Jerusalem or Babylon, God or Satan, but all attempts to show that its form is congruent with the narrative of the book of Ezekiel are ultimately unsatisfying.13↤ 13 See Harold Bloom’s “Commentary,” E843-44, and Randel Helms’ “Ezekiel and Blake’s Jerusalem,” Studies in Romanticism, 13 (1974), 133-40. Joanne Witke, “Jerusalem: A Synoptic Poem,” Comparative Literature, 22 (1970), shows that Blake’s four chapters are addressed to what were traditionally conceived to be the respective audiences of the four gospels. But she goes further and makes the largely unsubstantiated claim that “just as each of the evangelists’ gospels carries the image of one of the apocalyptic animals, so each of Blake’s four chapters bears a particular stamp of one of these creatures” (p. 275). Blake was very likely aware, as she notes, of S. Irenaeus’ comment—“Fourfold, Christ’s Gospels, fourfold the Cherubim whereon he sitteth” (p. 267, n. 6)—but Blake would have viewed this as a structural criticism of the gospels. The body of Christ is not separate from the chariot-throne in Jerusalem; it is the Cherubim body itself, as in “Ezekiel’s Wheels.” Blake’s prophecy is not a vehicle for vision; it is vision incarnate, the body of Los-Jesus. This method, which correlates the events of one book with those of the other, reveals that Blake is continually aware of Ezekiel’s prophetic strategies, even at times giving them an ironic twist, but it obscures Jerusalem’s most prominent symbols—furnace, hand, wheel—and, more important, its basic structural principle—successive transformations of Ezekiel’s Cherubim vision.

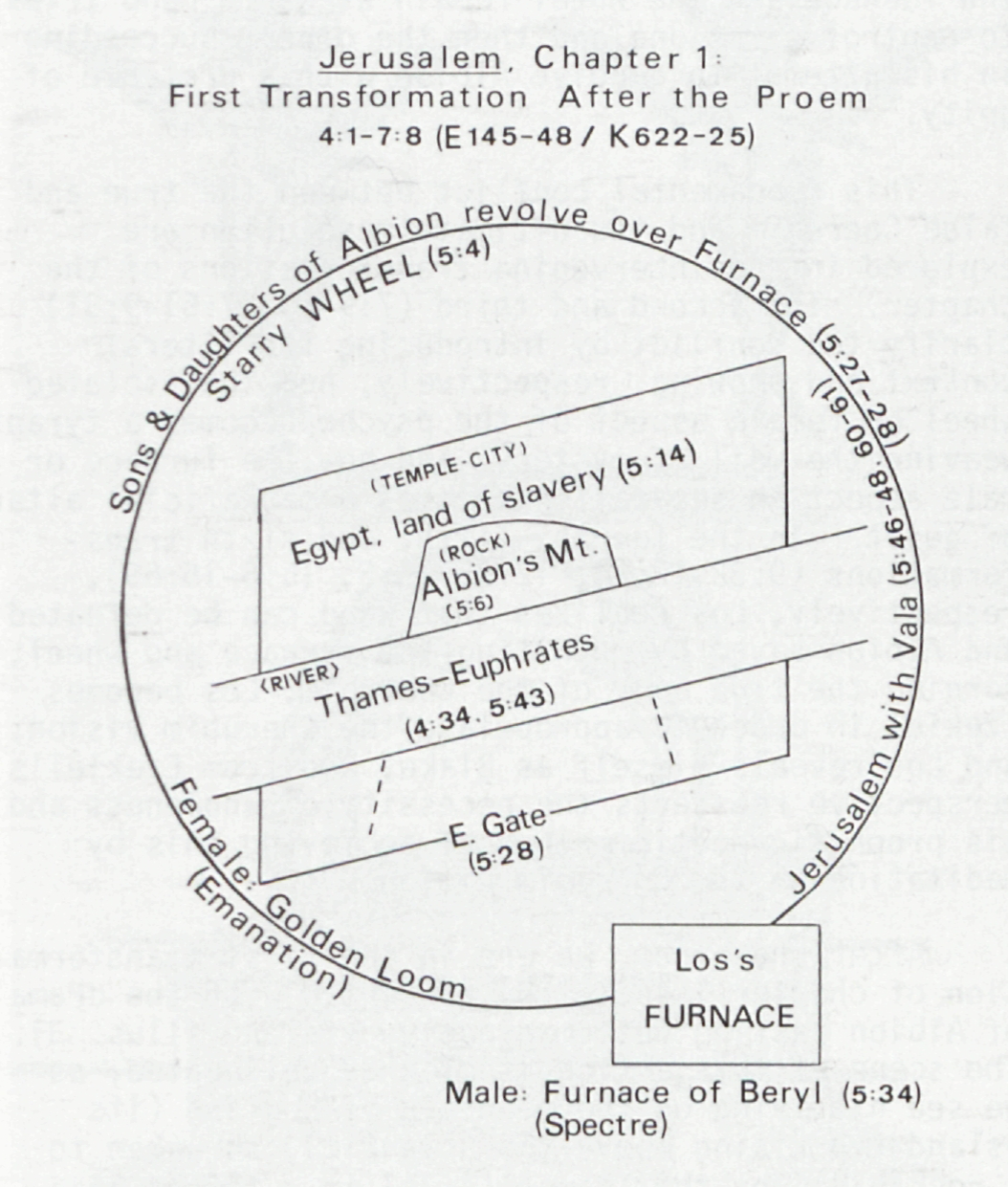

As an orator Blake is a literalist, both verbally in his expository, declarative language, and visually in his schematic tendency, as in the diagram on Plate 36 of Milton (IB252) of the Mundane Egg surrounded by the four universes. As a rhetorical and artistic strategy, the literalness of Blake’s paradigmatic scene that includes the sleeper on a rock by a river in a temple-city offers an advantage. The setting remains the same, giving Blake’s readers a point from which to get their bearings and, by its repetition, enabling them to grasp the substance of the prophecy. At the same time, however, it offers astounding variety, as the schema remains inviolate but the scene is transformed by Blake’s continual renaming: the sleeper is variously Blake, Albion, England, Los, or even Ezekiel himself; the rock is sometimes the English isle, the Rock of Ages, a sepulchre, an altar, Golgotha, Mt. Zion, or London Stone; the river is the Chebar, the Thames, the Euphrates, Tyburn’s brook, the Jordan, or the River of Paradise; and the temple-city is England, Jerusalem, Golgonooza the city of art, or Stonehenge the Druid place of sacrifice. The physical relations of these archetypal elements of the setting of Ezekiel’s vision do not change; the reader has the assurance of being rooted always in the same visionary landscape, though Blake shifts perspective, as he constantly changes the names of the visionary sleeper, the rock, the river, and the temple-city. The relationship between the furnace and the wheels in each transformation, however, as well as that between this vision and its setting, varies according to the audience.

Jerusalem consists, then, of a series of transformations of this paradigmatic scene and vision. Blake creates a tranformation by renaming the scene’s fixed elements—sleeper, rock, river, temple-city—and reestablishing the presence of the furnace and wheel. Each of these transformations, which embodies a different relation of exiled vision to landscape, as well as of wheel to furnace, is usually marked as a rhetorical subunit by a shift in speaker or by an introductory or concluding phrase: “such is my awful vision” (15:5), for example, or “Thus they contended” (9:31).14↤ 14 Blake’s playing the present fallen landscape off the past landscape of the beginning in Eden, however, does not constitute a transformation. I suggest that Jerusalem consists of twenty-eight transformations and tentatively submit the following table, which in the second chapter assumes Erdman’s order, though my argument is not changed by Blake’s alternate arrangement in Keynes; edition (bracketed numbers): Chapter 1—(1) Proem; (2) 4:1-7:8; (3) 7:9-50; (4) 7:51-9:31; (5) 9:32-12:24; (6) 12:25-15:5; (7) 15:6-16:69; (8) 17:1-19:47; (9) 20:1-25:16. Chapter 2—(1) Proem; (2) 28:1-30[34]:16; (3) 30[34]:17-35[39]:11; (4) 35 [39]:12-42:81; (5) 43[29]:1-46[32]:15; (6) 47:1-50:30. Chapter 3—(1) Proem; (2) 53:1-55:69; (3) 56:1-59:55; (4) 60:1-63:25; (5) 63:26-66:15; (6) 66:16-69:46; (7) 70:1-73:54; (8) 74:1-75:27. Chapter 4—(1) Proem; (2) 78:1-80:56; (3) 80:57-86:64; (4) 87:1-93:27; (5) 94:1-99:5. The number twenty-eight, which was to be the original number of chapters of Jerusalem (E731) and which Blake derives from the union of the twenty-four elders and the four beasts of John’s reworking of Ezekiel’s vision, signifying wholeness and redemption, is tempting as the total number of transformations. Twenty-eight cities rise up to restore Albion’s fragmented psyche and body (37[41]:23; 97:14). Thus, the number of transformations comprising Jerusalem would be for Blake the seven four-fold furnaces of salvation that Los (builder of the body) gathers around Albion’s altars (destroyers of the body) in the Druid temple of England (42:76-77), and the union of the sixteen sons of Jerusalem and the twelve sons of Albion (soul and body). Blake does not, however, always indicate his rhetorical subunits clearly enough to establish this figure indisputably as the total number of transformations. Hence, I fear the number is somewhat arbitrary at best, an idol at worst. These transformations, as I have provisionally indicated them (excluding proems), correspond roughly to the “scenes” of what Roger Easson terms, in “Blake and His Reader in Jerusalem” (Blake’s Sublime Allegory, ed. Stuart Curran and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr. [Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1973]), the “visionary drama” (p. 317): Chapter 1—Transformation (2) to Scene 1; (3-7) to 2; (8) to 3; (9) to 4. Chapter 2—Transformations (2-3) to Scenes 1-2; (4) to 3; (5-6) to 4. Chapter 3—Transformation (2) to Scene 1; (3) to 2; (4) to 3; (5-8) to 4. Chapter 4—Transformation (2) to Scene 1; (3) to 2; (4) to 3; (5) to 4. Though I disagree with Easson’s contention that Jerusalem is “composed of an allegoric drama embedded in an obscuring matrix of narration” (p. 316), because the latter reveals rather than obscures the landscape or necessary context of Albion’s vision, Easson’s association of Jerusalem with the drama, and Vala with the narrative of the poem (p. 319), parallels the split between vision (the drama of the furnace and the wheels) and landscape (the rock, river, and temple-city) central to my analysis. In the visionary body of the Cherubim, drama and narrative are unified, as is Jerusalem-Vala in Albion.

Each of the prophecy’s four chapters is prefaced by a prose introduction together with a proem, the verses in ballad or distich form, which set the scene and establish the rhetorical emphasis of subsequent transformations for its particular audience. The emphasis of the transformations of chapter 1 is on the judgment of the visionary, the prophet-poet Blake as he begins his poem, not only by God, who divides the “SHEEP” from the “GOATS” (E143/K620), but by his “Public,” who may not, as he says, forgive this “energetic exertion of my talent” (E144/K621). Consequently, the rock is Sinai’s “cave,” where the word was first given to man in what was commonly thought to be the origin of all writing, as well as the “caverns” of Blake’s ear, which receive the word. At the outset, Blake correlates body and landscape. The second chapter begins with a proem in which Blake has a vision of Albion sleeping on London’s Stone (the Roman mile-stone) beside Tyburn’s brook (place of human sacrifice by hanging) in Satan’s Synagogue (E170/K620) or Babylon. Emphasis on sacrifice sets the direction for an oration addressed to the “Jews.” This shifts in the third chapter, its transformations aimed at the “Deists,” to mental imprisonment, and, as a consequence, the Grey Monk of the proem, a type of Christ, is bound in a cell of stone in the Synagogue of Satan (E198-200/K682-83). This stone dungeon bursts open in the proem to the transformations of the last chapter and becomes Mt. Zion in Jerusalem (E229-31/K716-18). Prefacing an address to the “Christians,” the emphasis here is fittingly placed on the resurrection of the Lamb of God, who symbolizes the Imaginative Body as opposed to the vegetable or mortal body. This returns us to the hope that Blake expresses in his introduction to the “Giant form” of Jerusalem, that “the Reader will be with me wholly One in Jesus our Lord” (E144/K621).

One, that is, in the resurrected temple of Albion’s body, which Los-Blake struggles to build throughout the poem, and which we discover in the end begin page 69 | ↑ back to top

It is this body that is at stake in each of the transformations of Ezekiel’s vision that make up Jerusalem. The four faculties or “Zoas” of Albion’s body are at enmity, as are those of the body politic of the English people. That is, the Cherubim body is fragmented, the furnace and wheels warring against each other outside the gates of the temple, and must be restored to unity. Blake explores the nature of Albion’s disintegration by means of eight Cherubim transformations (not counting the proem) in chapter 1. In the first of these (4:1-7:8), Albion asserts his independence and denies his wholeness (4:23), expressed in the exile of vision—furnace and wheel—from its landscape—temple-city—(soul from body, Jerusalem from Albion), but fails to understand the true nature of his circumstances. Albion’s abstracting, self-dividing skepticism splits his person into a contemplator self and its object self. Furthermore, as his male and female aspects (Luvah and Vala) contend with each other, the furnace and the wheel also separate. It is not until the last two transformations of the chapter (17:1-19:47, 20:1-25:16) that Albion realizes his true situation. He is a victim, his independence a delusion. Blake symbolizes this by obscuring the redemptive furnace of Los and emphasizing the oppressive wheel of Vala. Because Albion mistakes the Covering Cherub for the Cherubim, begin page 70 | ↑ back to top the furnace and the wheel remain at war. Hand tries to control first one and then the other, succeeding in his attempt to deceive Albion with a pretence of unity.

This fundamental conflict between the true and false Cherubim and its ultimate resolution are explored in the intervening transformations of the chapter. The second and third (7:9-50, 7:51-9:31) clarify the conflict by introducing its literal context and showing, respectively, how the isolated wheel or female aspect of the psyche becomes a tyrant, weaving the veil of mystery, and how the furnace or male aspect in separation becomes a sacrificial altar of guilt. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth transformations (9:32-12:24, 12:25-15:5, 15:6-16:69), respectively, Los realizes that Hand can be defeated and Albion saved by reuniting the furnace and wheel, forging the true body of the Cherubim; Los becomes Ezekiel in order to appropriate the Cherubim vision; and Los reveals himself as Blake, who from Ezekiel’s perspective reasserts the necessity of wholeness and his prophetic-poetic method of achieving this by meditation on the Cherubim vision.

After the proem, we are in the first transformation of chapter 1 (4:1-7:8) presented with the drama of Albion casting out imaginative vision (illus. 3). The scene of this action is clearly delineated, as we see him lying on the mountain of England (its island tip rising above the Atlantic), shrunken to a rock (5:8), by the Thames (4:34) in a temple of sacrifice (5:15). Before him the “throne” (4:35) of the Cherubim (Ezek. 1.26, 10.1; Rev. 4.2) is dark and cold because the immortal human form has been dethroned, vision (Jerusalem) cast out and sacrificed (5:15,55). This is a spiritual or imaginative event, which causes Albion’s fall or vice versa. The order is irrelevant, for the event and its cause are simultaneous, but Albion’s fallen status becomes clear as we learn that the Covering Cherub (5:42) hovers over him on his bloody stone altar (5:6) beside the Euphrates (5:43) in Egypt (5:14), land of slavery.

Albion’s enslavement is a function of his dethroning the Cherubim, the disunity of the Four Zoas within his body. This casting out of imagination is dramatized by the banishment of vision from its scene, exiling of furnace and wheel from the temple-city-body, and their consequent separation. That is, as Albion self-divides, Jerusalem is cast out, splitting into a spectrous (destructive) and emanative (creative) portion. The former, or male part, descends into the “Furnance of Los” (5:28) outside the East gate of the city, just as the Cherubim stands before the East gate of the Lord’s house in Ezekiel (10:19). This is the “Furnace of beryll” (5:34) or appearance of the Cherubim (Ezek. 1. 16, 10.9). The latter, or female part, ascends out of the furnace as a pillar of cloud and smoke that becomes the “Starry Wheels” of a cosmic loom, which includes the sons and daughters of Albion revolving continually over the furnace in an attempt to destroy it, to “desolate Golgonooza; / And to devour the Sleeping Humanity” (5:27-30). Thus, the furnace or center of the Cherubim vision is divided from its wheels or circumference, both exiled from their proper landscape within the body of the temple-city. Blake summarizes this as “Abstract Philosophy warring in enmity against Imagination” or Satan against the “Divine Body of the Lord Jesus” (5:58-59). The horror of these divisions is intensified by Blake’s illumination on Plate 8 of the female in a cloud of smoke harnessed to an inauspicious moon-chariot, and on Plate 6 of the grotesque male Spectre revealing itself to Los as a bat-winged Covering Cherub (IB285, 287).

This male-female conflict between the furnace and the wheels is developed in the next two transformations, the Spectre’s first speech to Los (7:9-50) and Los’s reply (7:51-9:31). In their exchange the identities of the male and female parts of Jerusalem—“The Male is a Furnace of beryll; the Female is a golden Loom” (5:34)—are revealed, respectively, as Luvah, the figure of physical and political passion, and Vala, the veil of deceit. The Spectre assumes that Albion is still lying by the Euphrates, but his rock is renamed the Tower of Babel (7:19), the place of confusion existing in a “once admired” Palace “now in ruins” (7:16). This is the fallen Eden guarded by what Boehme calls the “devouring sword,” the false word. The Spectre’s harangue is an attempt, by misconstruing language, to confuse Los, that he might despair at his “Furnaces of affliction” (7:30). We find that Luvah is “sealed” (7:30) in these furnaces, while Vala feeds them in “cruel delight” (7:31) and joins the children of Albion in the wheeling loom of the zodiac, which in its separation has become oppressive. It is this seal, as in Revelation, which is opened at the end of Jerusalem to reveal the true Word, as Luvah-Jesus breaks the bonds of death and bursts the sealed tomb (Rev. 7:9; Matt. 27:66). The wheels of Vala, daughter of Babel, weave the “mantle of pestilence & war” (7:20), the “webs” of Religion which roll “outwards into darkness” (7:45-46). These wheels involve all the sons of Albion in their web, and the Spectre, mocking the true fourfold Cherubim, calls the son in whom all the others are “One,” a “Fourfold Wonder” (7:48).

The focus on the isolated wheels in the Spectre’s accusation shifts in Los’s reply to a focus on the separated furnace. The meaning of the wheels as the circumference of Albion, later “closed” (19:36), is clarified in this third transformation, as we learn that Albion “saw now from the outside what he before saw & felt from within” (8:25). Here Los attempts to transform Babel into “Zion’s Hill” (the Word). Los is now himself the visionary in a scene whose familiar landmarks are renamed, as he lies on the rocky tomb, which can open to reveal “Immortality” (7:56), by Tyburn’s Brook (8:1), in a temple garden. The Spectre, seeing the Lamb of God here, desires to supplant this true Cherubim vision with the “Abomination of Desolation” (7:70) as Jesus predicted (Mark 13.14; Matt. 24. 15-16). It is against such spectrous desire that Los struggles in his furnace. He knows he operates within the fallen condition, inasmuch as he labors outside the temple-city of Albion’s body, and as a consequence is himself split into Spectre and Emanation, but his labor at the furnace is Albion’s only hope for reintegration. Golgonooza is here in the furnace at the center. But the separation of the center from the circumference, inside from outside, furnace from wheels, occurs only when the begin page 71 | ↑ back to top unity of the Four Zoas or Cherubim body collapses. In this fallen state, what Albion before thought and felt as a whole becomes a neurotically self-conscious act, so that all spontaneity of emotion and thought is lost, and the result is a plague of doubt, guilt, and fear—a hoard of spectres.

Los’s preoccupation with the potential fall of the Word into the word, the Cherubim body become its parody, is also Blake’s. It degenerates, on the one hand, into the wheeling machinery of tyrannous political and religious abstraction and, on the other, into the fiery self-destruction of atomistic concreteness. Los’s spectres are Blake’s. At the outset of the poem Blake reminds us, in a rather confessional passage, that he is the visionary on the “Rock of Ages” (5:23), writing with a trembling hand beside the river Thames in Golgonooza-London, the city of art. The disintegration of the psyche and its necessary reintegration is not only true of the “Public” body, whom he addresses in this first chapter, but of himself. At its opening the identity of the “sleeper” is ambiguous (4:6); it can be Albion or Blake. Thus, his reintegration in his own work brings about redemption of the public as it enters into his images. With Los he rebuilds the imaginative human form, which he understands literally, perceiving language itself as a body or building (36[40]:58-59). His most personal fear, consequently, as a prophet-poet embarking on his greatest prophetic-epic task is that in the midst of extreme self-consciousness about his role and medium, as well as his powers, either language or his trembling engraver’s hand will fail—the hill of Zion become Babel. If the Spectre controls either, the Cherubim or true Word is undone and becomes the Covering Cherub of the warring wheel and furnace.

Employing his literal method, Blake introduces his own uncertain hand as the personage “Hand,” who contends with Los and is developed as a major, ambiguous figure in the rest of Jerusalem. Blake desires not to be the poet whose hand “trembles” with self-doubt, but the prophet in Ezekiel who boldly stretches “forth his hand” into the furnace between the wheels of the Cherubim and seizes the “coals of fire” (10:2,7). Blake in this role seizes his fiery etching acids and cuts verbal and graphic images into the metal plates of his prophecy. Significantly, Hand first appears to Los as a “triple-form” (8:34) mockery of the fourfold Cherubim, his “self-righteousness like whirlwinds of the north!” (7:73; cf. Ezek. 1.4). He takes the “bars” of his “condens’d thoughts, to forge them: / Into the sword of war” (9:4-5), which Los, in his furnaces, labors to form into a “spiritual sword. / That lays open the hidden heart” (9:18-19). As a Covering Cherub, the demonic parody of the four-fold Cherubim, Hand seeks to control both the furnace and the wheel. Sitting before Los’s furnace, he attempts to appropriate it for his own ends (7:71), and later he so dominates Vala that her loom becomes known as the “Wheel of Hand” (60:43).

This symbolic expansion of Hand as the supreme charlatan is not only suggested to Blake by the editorial signature of the three accusing Hunt brothers, but very likely also by the only human features in Parkhurst’s well-known drawing of the Cherubim, its three hands prominently and ludicrously

poking out from the right, left, and middle of the figure. Blake would have noted the cloven hoof of this silly creature and thought it fitting (illus.4).16↤ 16 On Blake’s derivation of “Hand” from the Hunt brothers’ editorial signature, see David V. Erdman, Prophet Against Empire, 3rd ed. (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1977), pp. 458-61; for Parkhurst’s drawing, see the plate between pp. 340-41 of Calmet’s Great Dictionary of the Holy Bible, ed. C. Taylor (London, 1800; rpt. Charlestown, N. C. : Samuel Etheridge, 1813), III, pl. II. E. J. Rose notes that on Plate 26 “Hand resembles the figure of Satan in the illustrations to Job” (“Blake’s Hand: Symbol and Design in Jerusalem,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 6 [1964], 49). The number symbolism evident in Blake’s opposition of the threefold Hand to the fourfold Cherubim is structurally, as well as thematically, significant. He tells us in Milton that “The Sexual is Threefold: the Human is Fourfold” (4:5), associating three with generation and death, four with imagination and the “Human Form Divine.” Thus, the numbers four and three and their derivatives, sixteen and twenty-eight, nine and twenty-seven, come to symbolize in Jerusalem, respectively, imaginative and fallen forms, Christ and Satan, the Hebrew four-headed Cherubim and the Greek three-headed Hecate. In this, as W. J. T. Mitchell concludes, Blake “reverses the traditional numerological preference for heavenly triads to earthly tetrads” (p. 203). Such a reversal misleads G. M. Harper, “The Divine Tetrad in Blake’s Jerusalem,” William Blake, ed. Rosenfeld, and Jane McClellan (with Harper), “Blake’s Demonic Triad,” Wordsworth Circle, 8, (Spring 1977), to conclude that Blake was “operating chiefly in the Neo-Pythagorean tradition” (Harper, p. 254) because his “divinity is tetradic rather than trinitarian” (p. 240), the number three being a symbol of form without substance (McClellan, p. 172). Harper specifically discounts, therefore, Blake’s debt to Ezekiel (p. 241), while Milton Percival, William Blake’s Circle of Destiny, and Désirée Hirst, Hidden Riches, respectively, note possible sources in the Kabbalah (p. 294, nn. 8, 26) and the Arora of Paracelsus (p. 68). Yet Blake’s source is clearly Ezekiel’s Cherubim vision, the fourfold man, who is Jesus the true God, form of the fourth in the fiery furnace, opposed to the abstract, tyrannously dogmatic trinitarian God. In this view Blake was very likely influenced by Parkhurst’s interpretation of the Cherubim, which he contrasts to the “material Trinity of Nature” (italics his) “adored” by the “heathen” (p. 343). The very body of Blake’s prophecy reflects this opposition, as Stuart Curran observes in “The Structures of Jerusalem” (Blake’s Sublime Allegory): “at the end of each of Jerusalem’s four chapters Christ the Eternal is invoked. But if we divide the poem into three parts, we find ourselves confronting climactic symbols of the fallen state” (p. 334), a structure recapitulated in each chapter. In his picture of Hand on Plate 26 (IB305), he presents the insidious Cherubim imposter as a fire-cloaked Christ in a satanic pose with nail-wounded hands, a mockery of the stigmata of the Christ rising in flames over Adam and Eve on Plate 31[35](IB310). When Hand ceases to exist in this form and is redeemed as the Cherubim (Ezek. 1.81, 10.21), however, he becomes the hand of God himself and, for Blake as poet-engraver, his own hand.As Hand’s deception is clarified, Los simultaneously becomes aware that Hand can only be defeated—parody restored to reality—by reuniting the wheel and furnace as living contraries in imaginative vision. Accordingly, Los dominates the next three transformations (fourth-sixth), forcing us to view Albion’s landscape from three points of view, respectively, that of Los himself, Los as Ezekiel, and Los as Blake. In the fourth transformation (9:32-12:34) Los remains the visionary by Tyburn’s brook, but the tomb of the previous scene, an image of regeneration (7:67), is now renamed a grave stone begin page 72 | ↑ back to top (10:54), because the Spectre of Man is fully revealed as the “Reasoning Power, / An Abstract objecting power than Negatives every thing” (10:13-14). He has entered the Temple (10:16) as the Abomination of Desolation and driven out the vision of furnace and wheels. In face of this, Los intensifies his labor outside the temple walls at the furnace (9:34-35), convinced that the encircling “Wheels of Albion’s Sons” are ultimately redemptive, “Giving a body to Falsehood that it may be cast off for ever. / . . . piercing Apollyon with his own bow!” (12:13-14). Thus, the wheel and furnace are not absolutely fallen in their separation. The wheels reach from the “starry heighth to the starry depth” (11:12) and so by imaginative labor can be used in their fallenness against Hand or the angel of the bottomless pit, as John saw in Revelation (9:11). And out of the furnaces comes imaginative space, Erin, to fill the void between the starry wheels in order to consolidate and clarify error so that it may be easily identified and cast out.

With this hope, Los appropriates the true Cherubim vision at its source, becoming in the next transformation (12:25-15:5) Ezekiel himself by the Chebar (12:58). From this perspective we learn that the “dark Satanic wheels” (12:44), taking the form of wheels “as cogs / . . . in a wheel, to fit the cogs of the adverse wheel” (13:13-14), are explicitly the fallen version of Ezekiel’s wheels within wheels. But we are focused on the product of the furnace: the “great City of Golgonooza” (12:46). With its “four Faces towards the Four Worlds of Humanity / In every Man,” this city is also the fourfold Cherubim body; “And the Eyes are the South, and the Nostrils are the East. / And the Tongue is the West, and the Ear is the North” (12:57-60). Los now lies on “Mild Zions Hill” (12:27) rather than on the grave stone, because even though this temple-city-body is surrounded by the “Twenty-seven Heavens” of death (13:32), it is a city of “pity and compassion,” a building of hope against the void. Los knows that the inside and the outside, the furnace and the wheels, of vision can be restored to unity because even the fallen “Vegetative Universe, opens like a flower from the Earths center: / In which is Eternity. It expands in Stars to the Mundane Shell / And there it meets Eternity again, both within and without” (13:34-36). The ultimate significance of this fact is revealed in Blake’s illumination at the bottom of Plate 14 (IB293), where we are reminded that Los is struggling on Albion’s behalf, who is pictured lying on a rocky tomb beside a river, with Jerusalem hovering over him as a six-winged Cherubim. The arch encompassing her may be interpreted as part of the satanic wheel or of the rainbow of promise accompanying the Cherubim in Ezekiel (1:28) and Revelation (4:3), which at the end of chapter 2, as Erin’s bow, encloses the wheels of Albion’s sons (50:22). This vision of Albion is a counterpoint to Los’s of Golgonooza, for here, without Los’s hope, he is sad and indifferent.

At this crucial point, hope discovered in the face of indifference, Los, Blake’s surrogate, gives way in the sixth transformation (15:6-16:69) to Blake himself. He is sustained by the previous Cherubim vision of the “Four-fold Man” (15:6) but prays for strength: “That I may awake Albion from his long & cold repose” (15:10). Blake is haunted, as when he began his task, by the same spectre of doubts and paralyzing “Reasonings,” as he says, “bruising my minute articulations” (15:12-13). Consequently, we again see fallen Albion lying on his rock (15:30, 16:27) by “London’s River” (the Thames, 16:40), his counties fleeing out of the temple-city gate (16:30), and as a result the wheels of the Cherubim vision are “wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic / Moving by compulsion each other: not as those in Eden: which / Wheel within Wheel in freedom revolve in harmony & peace” (15:18-20). These wheels of compulsion are those of mental and physical slavery, the “loom of Locke” and the “Water-wheels of Newton.” Hence, the furnaces separate from them and become for Blake the literal sacrifical altars (15:34) of English sweatshops.

Against this fallen condition, Blake reasserts his poetic-prophetic method, that is, transformation of the archetypal Cherubim vision: “All things acted on Earth are seen in the bright Sculptures of / Los’s Halls, & every Age renews its powers from these Works / . . . Such is the Divine Written Law of Horeb & Sinai, / And such the Holy Gospel of Mount Olivet & Calvary” (16:61-69). Los’s sculptures[e] are those of the Cherubim Blake refers to in his Descriptive Catalogue, “which were sculptured and painted on walls of Temples” (E522/K565).17↤ 17 Blake has in mind the “Cherubim of cunning work” on the veil of of the Temple (Ex. 26.1; II Chron. 3.14), “emblems” that Parkhurst claims the Jews felt “to be foundation, root, heart, and marrow of the whole Tabernacle” (p. 356; italics his). Ansari, “Blake and the Kabbalah,” notes the analogue of this in the idea of the cosmic “curtain,” described in the Book of Enoch, “on which is inscribed the pre-existing reality of forms and images of every event and passion” (p. 220). By transformation of this archetype, the body of prophetic art is created, the contrary union of wheel and furnace, “Law” and “Gospel,” the universal and the particular. This inheritance of art as body liberates Blake from the imitative bondage of classical art. The cavern of Mt. Sinai, where the word originated, is transformed into Mount Olivet, where the Word is revealed as a living body. The false body of error is cast off to reveal the naked beauty of the true Word. The fires of Los’s furnace forging a new temple-city-body are Blake’s etching fires creating the body of Jerusalem, as well as a new people of England, by removing a false covering.

Because Los-Ezekiel-Blake’s activity has been confirmed and the circumstances of Albion are now to be presented in their starkest form, along with his realization of his true state, the furnace is obscured in the last two transformations of the chapter (17:1-19:47, 20:1-25:16) by the wheels. We return to Albion lying on his rock by the Thames (19:40), but without the comfort, as in the chapter’s opening, of the city of Golgonooza in the promised land even as we observe Albion in Egypt. He is now emphatically in “Babylon the City of Vala, the Goddess Virgin-Mother. . . . Nature!” (18:29-30, 21:30), which Blake, like Ezekiel and John, draws into sharp opposition to the city of Jerusalem.18↤ 18 Ezek. 8-11, 40-48; Rev. 17, 21. See Farrer, pp. 167-68. Moreover, he ironically parallels the building of Golgonooza, earthly image of Jerusalem (12:25-13:27), with that of Babylon (24:25-35). “Nature” or Vala rules Babylon, the city of slavery, because Albion is held captive by what his age promulgated as the Natural Law of religion (Deism), politics (kingship) and poetics (the classics), epitomized for Blake in the cold, determinist wheels of the zodiac. Such an imaginative hold did this abstract philosophy have, that it was in his view ultimately responsible for the grinding down of individual people slaving at the looms in Spitalfields.

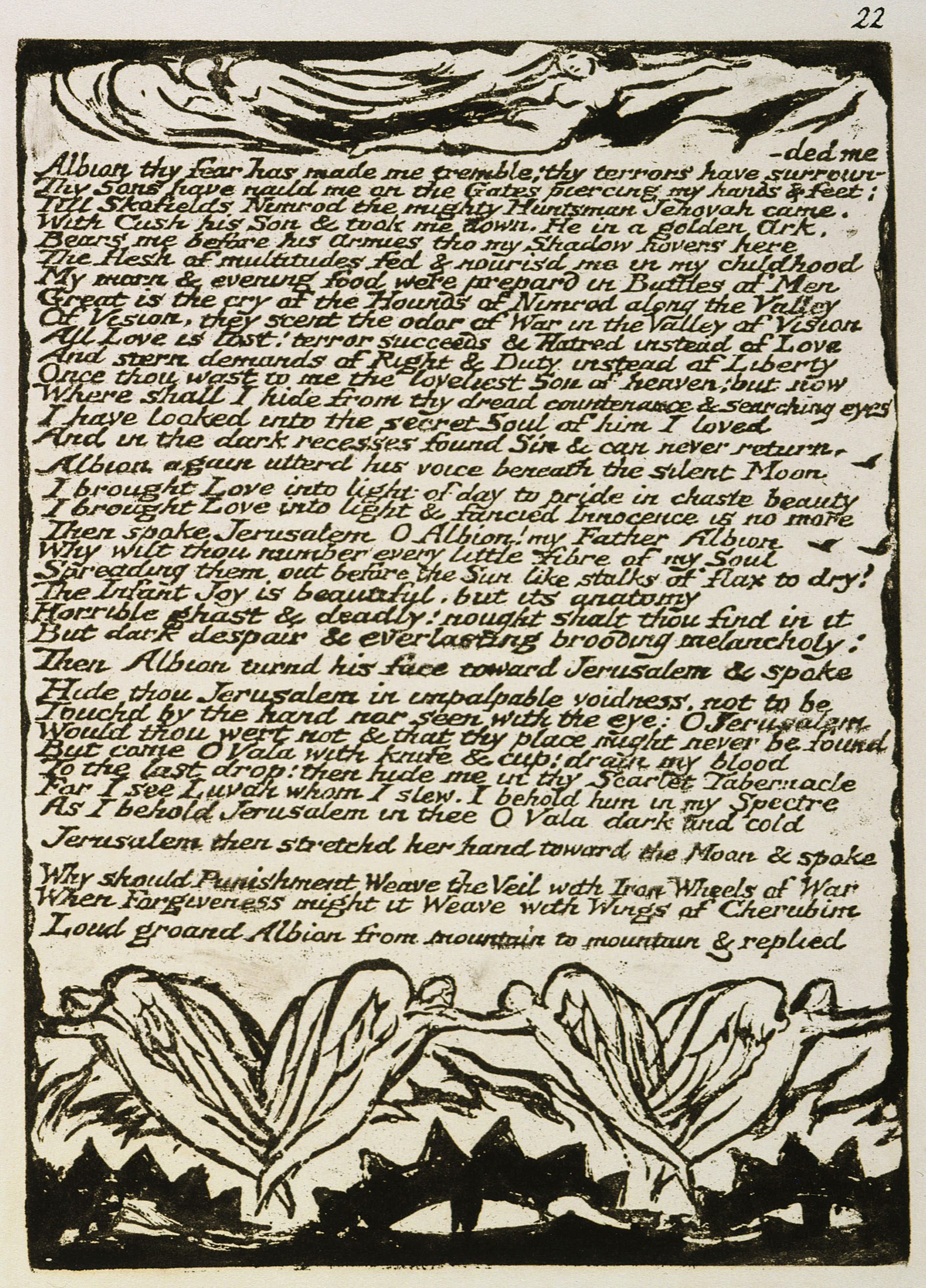

begin page 73 | ↑ back to topAlbion only becomes truly aware of his enslaved situation as he is able to recognize the Cherubim imposter. His wheels are absorbed into the great wheel of Hand (momentarily taken over from Vala), who reveals himself as the Covering Cherub, a demonic triple-form (18:8). Albion, sitting on a “rocky form against the Divine Humanity” (19:35) in this penultimate transformation of the chapter (17:1-19:47), is horrified by such “An Orbed Void of doubt, despair, . . . & sorrow” (18:4). Enslaved by Hand’s “Starry Wheels,” the whole of his inner or imaginative world is turned inside out, “His Children exil’d from his breast” (19:1). The product of Hand’s wheels is a deceitful veil, which in the last transformation of the chapter (20:1-25:16) covers Albion in the form of nature or the Mundane Shell (42:81, 59:7) and Moral Law (21:15, 23:22), a false Body (55:11, 65:61, 90:4) separating him from reality. The rock on which he sits, consequently, is renamed Luvah’s sepulcher (21:16), and he now realizes that his temple-city is Vala’s “Scarlet Tabernacle” (22:30). He yearns for the “Veil” to be rent (35:36), as it was at the death of Jesus (cf. 30:40, 55:16, 65:61; Matt. 27.51), and as Vala spreads her “scarlet Veil over Albion” (21:50), the exiled Jerusalem poses a pivotal rhetorical question: “Why should Punishment Weave the Veil with Iron Wheels of War / When Forgiveness might it Weave with Wings of Cherubim?” (22:34-35). Flames from the furnace of the true Cherubim consuming the wheels of war are pictured in Blake’s illustration at the bottom of Plate 22 (illus.

5). Albion’s identification of these wheels as imposters is crucial to his salvation; for only then is the Cherubim of forgiveness, the whirling love-sword mocked by the fiery star wheels drawn by four cowering old men pictured on the bottom of Plate 20 (IB299), revealed as imagination and liberty, Jerusalem herself.By successively renaming and shifting emphases, thus changing the relations of the archetypal elements of Ezekiel’s vision—the furnace and the wheel—in their exile from the visionary’s landscape, Blake completes Albion’s public judgment. Moreover, the reader’s, as well as Blake’s, is also complete. At the end of this chapter Albion realizes, as he did not in the opening transformation, why he is fallen and precisely what his situation is, admitting: “O human Imagination O Divine Body I have Crucified / I have turned my back upon thee into the Wastes of Moral Law: / There Babylon is builded” (24:23-30). By exiling imaginative vision from the temple-city of his own body, Albion crucifies himself. He sacrifices his body on the altar of “Law” and “demonstration” begin page 74 | ↑ back to top based on doubt in the connection of humans with each other and with the world. Blake survives his own self-judgment, exorcising the spectres of sorrow and self-doubt, by entering Ezekiel’s vision and creating with it his prophecy, which in turn invites his readers to enter into its “Visionary forms dramatic.” If they accept this invitation not to consider these images at a distance but to embrace them, they will be liberated with Blake from the bondage of doubt, and will wake from the nightmare of separation from each other and the natural world. They will receive their imaginative soul back from exile. Albion’s redemptive realization, that is, becomes our own as we enter into and move through Blake’s transformations of the Cherubim vision.

Blake continues to bring historical and personal imaginative errors under judgment throughout the rest of his poem by continually renaming and so shifting our perspective, until, in the final transformation of the last chapter, the wheel and the furnace unite as true Contraries and return from exile to Albion’s temple-city-body. We will examine in the remainder of this essay some pivotal transformations. In the second chapter, addressed to the “Jews,” the dialectic of the true and false sacrifice becomes more acute. Throughout, Albion in a familiar landscape sits on his rock (28:10, 34[38]:1, 38[43]:79, 43[29]:2, 48:4) beside a river (28:14, 30[34]:48, 37[41]:8, 43[29]:3, 44[30]:24, 45[31]:59, 47:2) in Babylon. But at the heart of the chapter Albion’s sacrificial body itself becomes a parody of the true body of the Cherubim. When Los, in the third transformation of the chapter (not counting the proem; 35[39]:12-42:81), personally enters “Albions House” (36[40]:24) or body, he opens his Furnaces before Albion (42:2), but “dark, / Repugnant,” he “rolld his Wheels backward / into the World of Death” (39[44]:5-9). Albion has sacrificed himself in a parody of the true sacrifice of Jesus, and, as a result, Los discovers in this temple “A pretence of Art, to destroy Art: a pretence of Liberty / To destroy Liberty” (38[43]:35-36). Albion’s twenty-eight friends, one in Los-Jesus (35[40]:4,46), respond “in love sublime, & as on Cherubs wings / They Albion surround with kindest violence to bear him back / Against his will thro Los’s Gate to Eden: Four-fold; loud! / Their Wings waving over the bottomless Immense” (39[44]:1-4). They offer to act as Albion’s guide into Eden, but are rebuffed because his will cannot be bent; he has chosen to close off his body to genuine self-sacrifice in Los’s Furnaces, thus mocking with his own body the imaginative body of the One Man of the Cherubim.

The sacrifical body of chariot that Albion chooses is pictured on the lower half of Plate 41[46] (illus. 6) in all its horror, as a false body, and all its humor, as a parody of the Cherubim. This chariot vision, its chassis and wheels formed by serpents, which Blake associates with the Druid Serpent Temples of stone devoted to human sacrifice and nature worship, is revealed as the Covering Cherub. The serpent heads thrust forward, but their deathly rigid bodies have hardened into yokes and wheels that insure no escape or movement. Flames from the “Furnaces of Los” glimmer feebly beyond the wheels, while each beast of Ezekiel’s vision (Ezek. 1.10) is satirized. The shaggy lion manes serve only to make the men’s faces appear more pompous in their grim determination to move ox-hoofed bodies, clearly fixed to the ground. And the emaciated eagle-men on their backs, who hold forth quills as if simultaneously wishing to give them away and commanding the chariot to move on, satirize the prophet proclaiming change. Instead of the movement that Ezekiel emphasizes in his vision, where every one “went straight forward” (Ezek. 1.7, 12, 17, 23; 10.11, 22), this chariot is totally static, an image of paralyzing self-doubt. The two horns of the maned heads curl into serpentine coils and end in hands, each gesturing in opposite directions.19↤ 19 Blake develops this parody in an illustration to Dante’s Purgatorio, “Beatrice addressing Dante from the Car” (c. 1825), reproduced by Martin Butlin in William Blake: Catalogue of the Tate Gallery Exhibition (London: Tate Gallery, 1978), pl. 74. The vortex of the wheels, Albert S. Roe observes, Blake’s Illustrations to the Divine Comedy (Princeton, N. J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1953), are “deliberately introduced by Blake” in a departure from the text (p. 166). The wheels of Ezekiel’s vision are perverted in this image of death, as is the fourfold man by the three female forms in its whirlpool. Moreover, the four beasts are ludicrously depicted. Blake’s caricaturing of the Zoas goes back to an early sketch in Vala, p. 136; John E. Grant briefly discusses the larger context of such caricature in “Visions in Vala: A Consideration of Some Pictures in the Manuscript” (Blake’s Sublime Allegory, pp. 198-99, n. 60). Albion, who sits with Vala in the chariot, passively lets the reins drop. His face mirrors the lion men’s, its determined expression working against his body, which has become the sacrificial altar of stone itself.

If the “Jews” worship the paternal God of vengeance and sacrifice, the “Deists,” whom Blake addresses in chapter 3, worship the maternal Goddess of Nature and Natural Law. She is both womb and temptress, protector and tyrant. As Deist, Albion is thus imprisoned in the coils of serpent nature. And as he sleeps (60:69), in the third transformation of the chapter (not counting the proem; 60:1-63:25), by Tyburn’s brook (62:34) in the city of Babylon (60:23), his rock is renamed a Dungeon of Babylon (60:39) where he is forced to labor at the “iron mill” (60:59). This is the mill wheel in his mind of abstract generalizing that grinds all the minute particulars of art and life into nothing. And though the Divine Vision appears in Los’s furnace outside the city (60:5), even walking among the “Druid Temples & the Starry Wheels” (60:7), Jerusalem’s reason has become the “Wheel of Hand” (60:43); and Albion returns to his labors in the dungeon, the chariot of the Cherubim having become a raging war chariot (63:11).

The problem with the “Christian,” though they claim to worship the Cherubim, the resurrected body of Albion-Jesus or imaginative liberty, is that they habitually mistake the mortal for the resurrected body. At the center of Blake’s oration addressed to them, consequently, are two tranformations of the Cherubim (80:57-86:64, 87:1-93:27) which separate the true from the false body. In the first of these, Albion sleeps by the Euphrates (82:18) on a rock (84:7) in Babylon (82:18), a landscape revealing his imaginative death. But Los works outside the gate at his furnace, despite the “Spindle of destruction” (84:30) whirling overhead, to give Hand a body so that the unimaginative may be cast out once and for all. We are reminded that the furnace and wheel are still separate—the “Male is a Furnace of beryll, the Female is a golden Loom” (90:27)—and, like Hand in the furnace, the “Starry round” (88:2) is revealed for what it is, the false body of the “Dragon” Antichrist (89:53), serpent Satan. At the same time, however, Los glimpses their potential unity in his vision of the still imprisoned Jerusalem as the Cherubim, a temple-body with “Gates of precious stones” (85:23). Her “Form is lovely mild, . . . Wingd with Six Wings,” and her bright “forehead . . . Reflects Eternity” (86:1-15). More important, Los sees in her “translucent” body her own landscape, “the river of life . . . / the New Jerusalem descending out of Heaven” in “flames,” clear as the “rainbow” (86:18-23). Here is a reminder of Erin’s promise in her rainbow that the wheel and the furnace will be united in Jerusalem, who will return to Albion.

begin page 75 | ↑ back to topThis perspective opens out in the next transformation as Albion becomes the dreamer beside a river, renamed the Thames (89:20, 90:47), on a rock, renamed Golgotha or the Sepulchre of Luvah-Jesus (92:26). His landscape now reveals the imminence of his awakening and resurrection; the body of imagination, the Lamb of God, will burst open the sepulchre and rend the veil in Albion’s “triple Female Tabernacle” of “Moral Law” (88:19). Accordingly, Los manages to give Hand a body, “Satan” the “Body of Doubt that Seems but Is Not” (93:20) and is cast off at the resurrection. We are also forced to view the destructive wheels of the loom overhead weaving a mortal “Womb” (87:14). The Covering Cherub, moreover, in contrast to Los’s vision of Jerusalem in the previous transformation, is presented as the false temple-body, a demonic parody of the Cherubim (89: 14-51). Instead of reflecting the unity of eternity, the Covering Cherub’s mortal body is fragmented into a “Head, dark, deadly” whose “Brain incloses a reflexion / Of Eden all perverted,” while his “Bosom wide reflects Moab,” his “Loins inclose Babylon on Euphrates,” and his “devouring Stomach” is a tabernacle of “allegoric delusion & woe.” This is the body of “Minute Particulars in slavery, . . . / Disorganizd” and sacrificed to “Generalizing Gods.” Torn to pieces, his “ribs of brass, starry, black as night,” mock the rainbow of true vision. He lies brooding on “ridges of stone” beside “the Dragon of the River” Euphrates in a parody of Ezekiel’s landscape, while his “Furnaces of iron” and black wings mock Ezekiel’s vision. Furthermore, in a parody of Los’s Jerusalem-Cherubim witnessing to the unity of vision and its scene, his stomach devours its landscape “From Babylon to Rome / . . . the World of Generation & Death” (89:48-49). Hence, the Covering Cherub can no longer be mistaken for anything other than a “majestic image / Of Selfhood, Body put off, the Antichrist” (89:9-10). So ends his masquerade.

This apocalyptic consolidation of error clears the way for the resurrection of the true body. The furnace and wheels of the Cherubim are at last united in the final transformation of Jerusalem (94:1-99:5), and together they return from exile, becoming the temple-city-body of Jerusalem, as in Revelation (21.2-3,22-23). The body now becomes its own scene, the scene its body. Albion’s rock (95:1) is renamed an “Immortal Tomb” of “Resurrection” (94:1, 98:20), and the ocean beside him renamed a river of Paradise (94:6, 98:25). In deathly slumber he moves “Beneath the Furnaces & the starry wheels” (94:2). He has made attempts to move before, getting only as far as the East gate of his temple-city, but now as the Four Zoas rise into “Albion’s Bosom” (96:42), he awakes from death and walks in “flames, / Loud thundring with broad flashes of lightning” (cf. Ezek. 1.13-14; Enoch 14.12; Rev. 4.5), “speaking the Words of Eternity in Human Forms” like a prophet (95:5-9). He takes the living “Bow” of the starry wheels, which Erin redeemed, making it into a bow that fires “arrows of flaming gold,” and, one with Los-Jesus, throws himself into the “Furnaces of affliction” (96:35) uniting wheel and furnace. These Contraries in turn become “Fountains of Living Waters flowing from the Humanity Divine” (96:37) into the temple-city-body of “Golgonooza” (98:55), the “Four Living Creatures, Chariots of Humanity Divine” (98:24). Thus the furnace and the wheels, for the first time in Jerusalem, are recalled from exile. Albion’s landscape and vision are unified; its emblem is his embrace of Jerusalem, together forming a flame-engulfed bow on Plate 99 (IB378). The center and circumference are no longer separate because of the “rejoicing in Unity / In the Four Senses” of the Cherubim and “in the Outline the Circumference & Form, for ever / In Forgiveness of Sins” (98:21-23), which is the only true Christianity, the religion of Jesus or Imagination. This is Albion’s ultimate liberation from the idolatry of the deceitful mortal body, his freedom from the mind’s male and female errors, worship of an abstract paternal God or maternal Nature.

In Albion’s resurrected body, the new Jerusalem, there is no accuser causing fear and doubt because there is no self-division. Here, in Blake’s last Cherubim transformation of his phophecy, the “Hand of Man,” like that of the man in linen commanded to go between the wheels of the Cherubim and gather coals to scatter over the city in a prophetic gesture (Ezek. 10.2), “grasps firm between the Male & Female Loves” (97:15), between the furnace of beryl and the wheels of the loom. Blake has not arrived at ecstasy, but he has reached out with his firm engraver’s hand and achieved the prophetic end of rebuilding a people and a city by transformations of Ezekiel’s Cherubim, whose wings weave forgiveness of oneself as well as others. Its body is for Blake a symbol of the unity of man and his imagination, of inside and outside, the visual and the verbal; but it is also a body in the most literal sense—Jerusalem itself.