article

begin page 170 | ↑ back to topA BOOK TO EAT

Mitchell’s Blake’s Composite Art is “open” both in its cordial, transformative embrace of earlier readings of Blake and in lighting the way to further interpretation. In the suitably named final chapter on “Living Form” Mitchell improves on previous readings, for example, of Jerusalem 76 and 78, refining the ironies of their complexity persuasively toward the positive pole.1↤ 1 W. J. T. Mitchell, Blake’s Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1978). In the Crucifixion picture (J 76), he asks, which sun is the natural sun, which the spiritual? “The answer is both, or neither, because the important sunrise in the picture is Albion himself, rising like Samson (whose name was translated as ‘sun’), shaking off his spiritual darkness and blindness” (p. 211). Mitchell illustrates the point that Blake’s meaning derives from “traditional renderings of the Crucifixion with St. John the Evangelist (the only disciple who witnessed the Crucifixion) at the foot of the cross” and whose gesture there is repeated in Blake’s “Glad Day” posture—in Albion rose and in the standing Albion of Jerusalem 76.2↤ 2 Irene H. Chayes tells me that Blake could have encountered directly an earlier tradition from which these “renderings” were derived.

Following close after this, the melancholy, bird-headed figure in Jerusalem 78 must represent living genius more positively than ironists have supposed, Mitchell pleads. Here again, “the iconography of St. John” as eagle-headed prophet is shown in pictorial analogues that are to dispel our clouds of doubt, while the brooder’s posture is said to be alluding to the symbolism of Dürer’s Melencolia I. We may hesitate to agree that the emblem of Plate 78 constitutes “a rather direct transposition of the description of Los in the accompanying text” but are compelled to recognize that it gives this text important coloring: “Los laments at his dire labours, viewing Jerusalem, / Sitting before his Furnaces clothed in sackcloth of hair.” In effect Albion as St. John and Los as St. John are becoming one. If the eagle-man is meant also to recall Hand with his “rav’ning” beak (as I suggested in The Illuminated Blake), then surely, urges Mitchell, “we are seeing him transformed here from predatory adversary to prophetic ally, using his eagle’s head for vision, not violence.” He cites the Hand of Man that “grasps firm” in Jerusalem 97 and reminds us that St. John is the patron saint of engravers, printers, makers of books—the wheels of Hand!

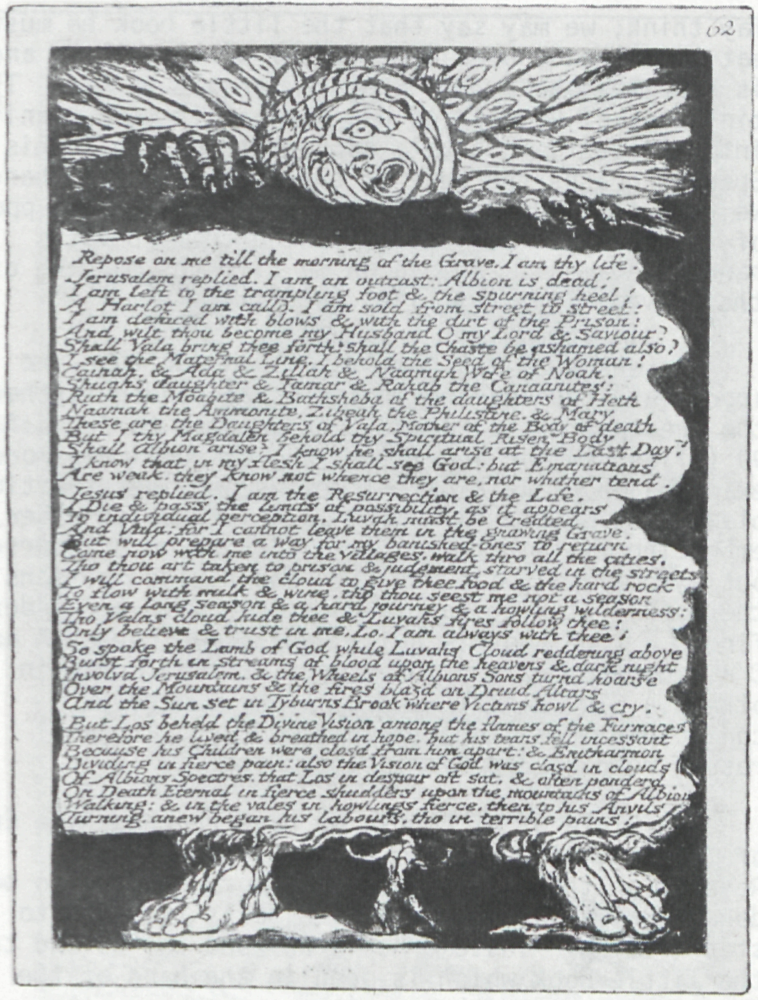

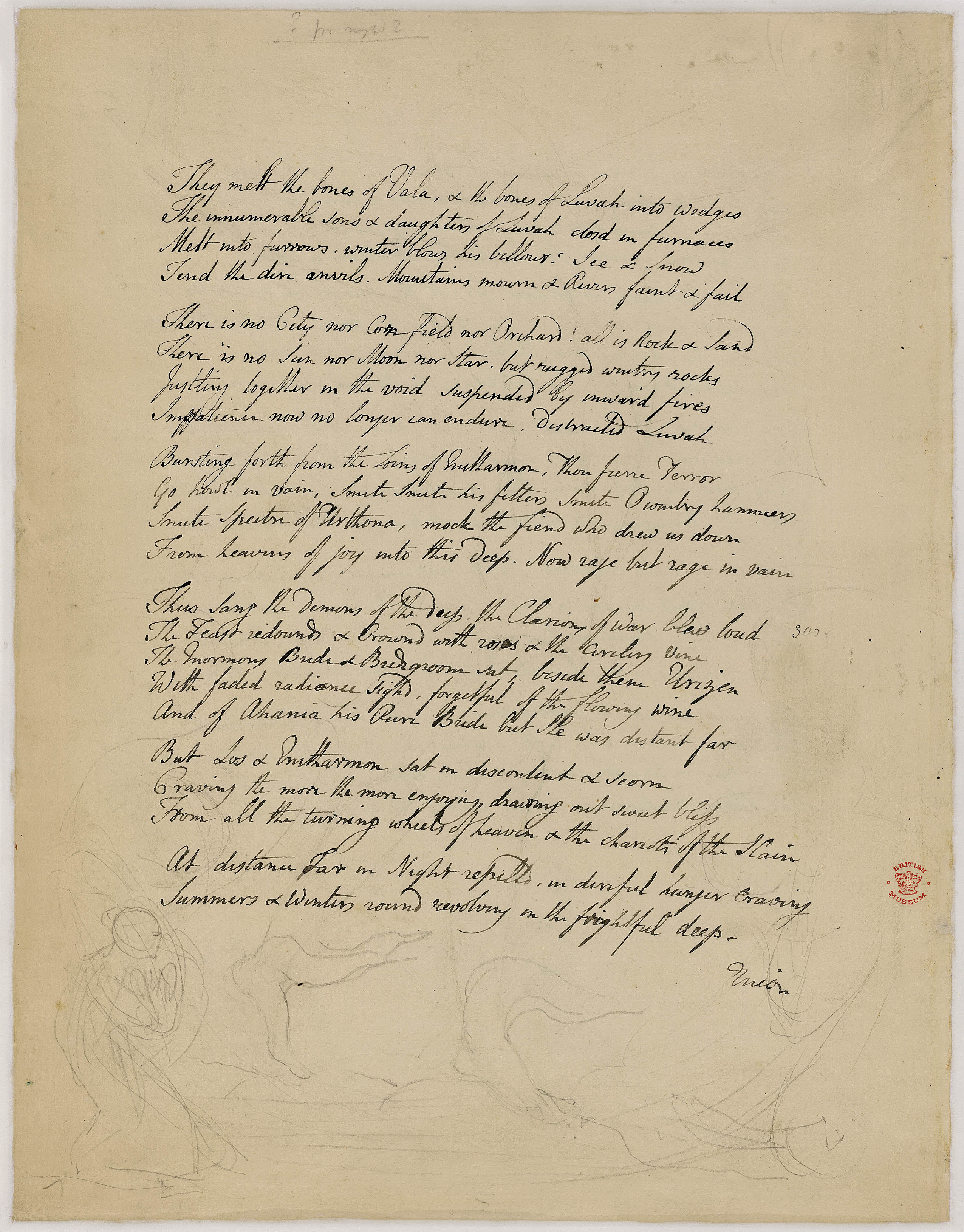

“It is clear that there is a great deal more to be said on the matter of the presence of St. John in Blake’s verbal and visual art.” Indeed there must be. And Mitchell proceeds to discover his presence in that complex and baffling image of the flaming giant in Jerusalem 62 (illus. 1). Some of the components were recently clarified by Irene H. Chayes in the Bulletin, details that place this anguished giant between a Polyphemus figure in Tibaldi and the figure of Giant Despair in Blake’s Bunyan designs.3↤ 3 “Blake and Tibaldi,” Bulletin of Research in the Humanities, 81 (1979), 113-25, illus. Mitchell suggests that the giant whose body is covered by the text “is” the “‘mighty angel’ whose feet are described as ‘pillars of fire’ in Revelation 10:1, and the tiny figure between his feet is St. John.” Before the doubter can raise a hand—isn’t Blake’s giant being consumed, to free the text from his clutch?—Mitchell shows us Blake’s own painting of The Angel of the Revelation (illus. 2), between whose flaming legs sits, not stands (but Blake in Jerusalem 62 has moved from writing table to furnace) a tiny St. John. One hand of the angel is “stretched downward, holding the little book that St. John will consume, the other ‘lifted up . . . to heaven’; Rev. 10:5.” In the Jerusalem context, of course, this tiny figure is Los. In the context of The Four Zoas, a similarly flaming pair of feet, on page 16 (illus. 3), are identifiably Christ’s (or Luvah’s), and the alarmed little figure observing them must be Vala, who exclaims: “I see begin page 171 | ↑ back to top not Luvah as of old I only see his feet / Like pillars of fire travelling thro darkness & non entity.”4↤ 4 This pertinent text, FZ 31:9-10, is cited by G. E. Bentley, Jr., ed., William Blake’s Writings (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), II, 1100n., and he too can see only the feet, “two feet walking toward the right.” Evidently lacking a photograph that shows the lines of the body, Bentley supposes that the feet are “not related to the large sketch” on the page which “seems to have represented Christ.” (Comparison with the drawing of Christ walking toward the right on FZ p. 116 will reveal the same head and arms positions and similar body lines. On p. 16 Blake first drew bowed, kneeling angels in the lower corners, then added the small gowned figure [of Vala] partly on top of the drawing of the angel at the left.)

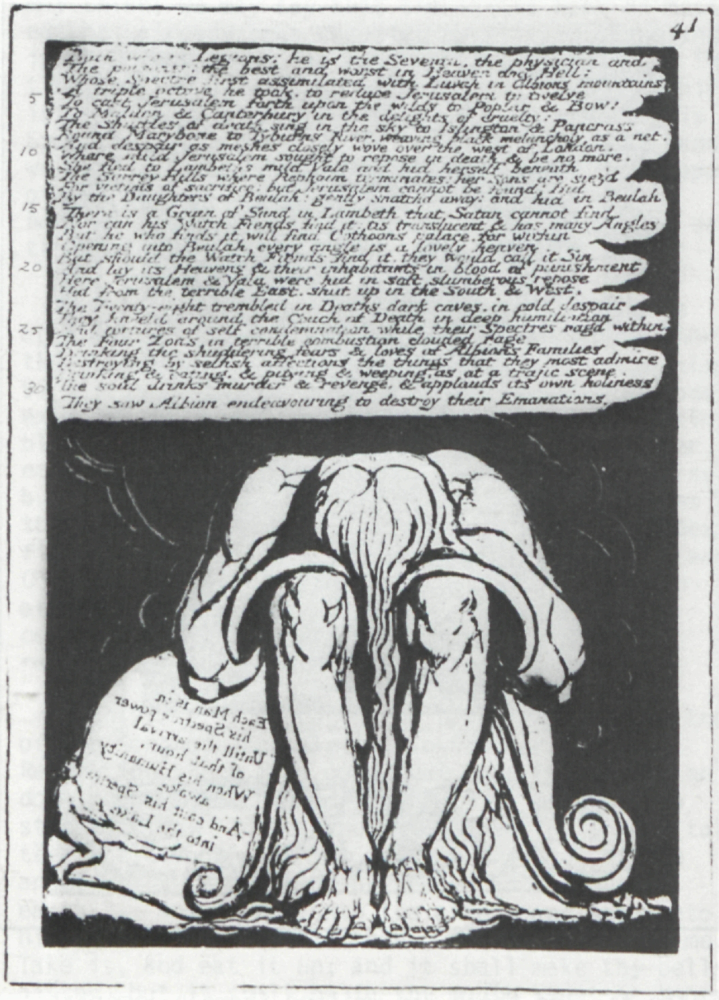

Mitchell might have called our attention to the little figure in Jerusalem 37 [41] who represents Blake as author, equipped like St. John with pen and scroll but busy writing at the feet of the sleeping giant Albion. This giant appears, at least, to be sleeping but may be secretly reading Blake’s scroll as it crosses his belly.

But other things draw Mitchell’s attention. One of these is the posture of the central figure in the second titlepage of Blake’s Genesis manuscript.5↤ 5 Mitchell, failing to recognize this figure as Adam (as the context requires), surmises that this is “one of the four figures of divine inspiration” and therefore “our ‘mighty angel’ of Revelation” (p. 212). Both figures have raised right hands, and near Adam’s right foot is St. John as an eagle-beaked “zoa.” But Adam’s left hand is half raised, not lowered; his feet are not in flames; his eyes do not, as the angel’s, look up to heaven for inspiration but forward. The halo around Adam’s head does make him a sort of angel, but it implies a more striking role change than that. Viewers of Blake’s The Fall of Man are startled to recognize in the central figure of that picture, walking forward on the earth, not an angel leading Adam and Eve out of Paradise but Jesus himself, with flaming halo. Now, in the Genesis titlepage, Christ gives that role to Adam, the central, haloed figure standing atop the curve of the earth and flanked, further back stage, by Jesus and Jehovah in luminous clouds but without particular haloes. Adam’s own naked body is incorporated into the design as a support for the letter “I”—figleaf turned into selfhood, we might think, but for the positive, flourishing spirit of the whole design. Adam’s “head is framed by a rose-pink circle forming a kind of halo behind which the red dawn of a new day is streaked across the sky. With his right hand he grasps the Pledge of the Redemption from Christ. The left arm is flexed at the elbow, but the hand is unfinished”; Piloo Nanavutty, “A Title Page in Blake’s Illustrated Genesis Manuscript” (1947; rpt. pp. 127-46 in Robert N. Essick, ed., The Visionary Hand [Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls,[e] 1973], illus.) The verb “grasps” is wrong for Adam’s open, receptive hand; but the details and identifications in this article are generally sound. Here Albion/Adam is wide awake and standing free, as/because he is receiving inspiration from his friend Jesus (above him on his right), not in book form but as a scroll that loops gracefully down from the left hand of Christ into the palm of the open right hand of Adam. Most auspicious is the living flow of text from Jesus’ hand through the scroll to the hand of Adam and through his body to the letters of our Book, “GENESIS.” In The Angel of the Revelation St. John’s attention is not upon the open book in the angel’s hand. He is busy writing about the seven horses and horsemen, or rather, noticing with grim face the textual intrusion of the Angel’s body upon his penned account of the horsemen (Rev. 9). But it is time to return our attention to Jerusalem 62.

As Irene Chayes has noted, the imminence of a Last Judgment is suggested by the burning giant’s triple headdress of serpent, sunrays, and eyed peacock feathers (with rainbow colors in the Mellon copy). “Seen in relation to the page of text he is at once displaying and trying to rise out of, the giant of Jerusalem 62 . . . may be the emblem of an ultimate inner enlightenment and transformation that will accompany the burning away of the physical body: a Last Judgment in Blake’s sense, which supplements the ‘Divine Vision among the flames of the Furnaces’ (62:35) Los is beholding” (p. 124). But his eyes tell us how late it is. If Adam in the Genesis page looks forward with the world all before him, and the Angel of the Apocalypse looks upward for guidance, the anguished giant in Jerusalem 62 has almost stopped looking and has obviously begun crying out. “Slanting and oval in shape,” notes Chayes, “with each iris diminished to a pinpoint, his already conventionalized eyes are multiplied and repeated as an abstract pattern on the feathers that surround his head, as though in a peacock’s fan.” Among all these analogues, his is the only open mouth. It is later than St. John

As we grasp Mitchell’s text in our turn, we appreciate his leaving it for us to ponder further the presence of St. John. Let us turn to Jerusalem 99 (illus. 4) for a culminating yet sublimely modest example, on Blake’s part. Let us consider the tiny black book in the left hand of the aureoled elder, embracing his youthful friend (Jerusalem of course, but symbolically all the lost and divided persons in the book) yet keeping his book open with his index finger. (The book is quite visible in copies A and C and posthumously printed ones, but obscured in others.) In The Illuminated Blake I merely conjecture that “Tomorrow Urizen (Jehovah) will resume reading the Everlasting Gospel.”

On Plate 99 of course we have reached “The End of The Song of Jerusalem.” In Chapter 10 of Revelation there is a good deal more reading to be done. But a voice from heaven tells St. John to stop writing. Instead he is advised to “Go and take the little book which is open in the hand of the angel which standeth upon the sea and upon the earth.” “And I went unto the angel, and said unto him, Give me the little book. And he said unto me, Take it, and eat it up; and it shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.” And St. John tasted and ate and found that this was true.6↤ 6 The face of Dürer’s St. John expresses an awareness of the bitter taste even as he takes his first bite of the text. But Dürer’s symbolism conflates the whole process of transmission; the book his St. John is writing is already filling with text. Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr., from whose Visionary Poetics: Milton’s Tradition and His Legacy (Huntington Library, 1979) I borrow the Dürer picture (illus. 8), cites this as symbolizing the “prophetic moment” from which poetry issues with dramatic intensity (p. 55). “And he said unto me, Thou must prophesy again before many peoples, and nations, and tongues, and kings.” In Jerusalem 62 if we see Adam/Albion in the giant, we see that he is not yet risen as the sun—his rising is shown and described on Plate 95—but that he is bearing the whole weight of the text, like the Titan Enceladus when flattened by Mount Etna (theatrically depicted in early illustrations of Ovid: see illus. 6).7↤ 7 A picture book available in Blake’s day in various formats and full of likely influences is The Temple of the Muses; or, The principal histories of fabulous antiquity, represented in sixty sculptures; designed and ingraved by Bernard Picart le Romain, and other celebrated masters (Amsterdam: Z. Chatelain, 1733; derived from Tableaux du Temple des Muses [Paris, 1655]). We cannot see the feet of the giant “Enceladus burried under Mount AEthna” (sic), but the rock looks like a text in his mouth (and gripping hands). Is the fire in the belly of the mountain in combat with the relayed Jovian thunderbolts? (Compare the ambiguities of fire in Blake’s “Spiritual form of Nelson.”) In this same collection, the Picart “Andromeda” seems to me more like an American Indian and closer to Blake’s Oothoon than is the derivative version by Bartolozzi reproduced by John Beer in his “Influence and Independence in Blake,” in Interpreting Blake, ed. Michael Phillips (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1979), pp. 196-261; Beer explains his preference in n. 22, p. 211. Indeed, the text is bitter in his belly. Yet he is no longer drowsing while Blake writes, as in Jerusalem 37 [41] (illus. 7) where Blake is preparing a text for Albion to read in the mirror of annihilation. He is now awake, holding for us to read—we are his mirror—the dialogue of Jerusalem and Jesus “among the flames of the Furnaces.” Dare we become what we read here, finding even the honey of “hope” amid the bitterness of “a hard journey” and “terrible pains” (J 62:27, 35-36, 42)? We can see from Plate 100 that the prophet’s work is never done.

The modesty of Blake’s handling of this emblem may impress us. But Harold Bloom, with whom I have just discussed the eating and digestion of the book, noted that Blake’s lifelong immersion in the language of the Bible must have developed as a matter of second nature his prophetic recourse to the company of Isaiah and Ezekiel. Look up Ezekiel 2 and 3, he advised. “And when I looked, behold, a hand was sent unto me; and, lo, a roll of a book was therein . . . and it was written within and

begin page 173 | ↑ back to top without: and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe. Moreover he said unto me, Son of man, eat that thou findest; eat this roll, and go speak unto the house of Israel. So I opened my mouth, and he caused me to eat that roll. And he said unto me, Son of man, cause thy belly to eat, and fill thy bowels with this roll that I give thee. Then did I eat it; and it was in my mouth as honey for sweetness.” The Lord does not mention any embittering of the prophet’s belly. But he expresses an irony which Blake, often bound to “sullen contemplations in the night,” well understood. If I had “sent thee,” the Lord tells Ezekiel, “to many people of a strange speech and of a hard language, whose words thou canst not understand . . . they would have hearkened unto thee.” But his own nation, who could of course understand, “will not hearken unto thee; for they will not hearken unto me. . . . ” Nevertheless the prophet is sent; he must speak to his fellow countrymen “whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear.” The Lord hardened Ezekiel’s “forehead against their foreheads.” “So the spirit lifted me up . . . and I went in bitterness, in the heat of my spirit; but the hand of the Lord was strong upon me.” Thus Blake in his youth wrote, with a “voice of honest indignation,” a bible “which the world shall have whether they will or no” (Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 12, 24) and in times of stress was hardened to set “my forehead against their foreheads” (Letter of 6 July 1803).But how does a message have effect in a world which will not read? At this point a fellow scholar, begin page 174 | ↑ back to top

For as the rain or the snow comes down from the heavens,Blake approximated the same extra-communicative sentiment in some of his remarks to Crabb Robinson. Utterance was all: “the moment I have written I see the words fly about the room in all directions—It is then published and the Spirits can read. . . . I have been tempted to burn my MSS. . . .” Robinson objected that the Manuscripts were not Blake’s property but the Spirits’: “You cannot tell what purpose they may answer. . . . He liked this.”

and returns not thither except it have watered the earth,

and, having made it give birth,

made it sprout growth,

have provided seed for the sower,

and bread for the consumer,

so shall My word be,

that which issues from My mouth:

it shall not return to Me empty,

but it shall have accomplished what I desire,

and shall have prospered that as to which I sent it.

From another perspective, the text clasped by the giant hands in Jerusalem 62 can be seen as the stone lid of the tomb which is everyone’s “till the morning of the Grave”; and the words are Christ’s (whose “voice” is heard by Jerusalem on the preceding page) yet appear to accompany Albion’s gesture (“Repose on me”) even while he is looking offstage, with those multiplying eyes—toward the voice?

![A[lbrecht] D[ürer]](img/illustrations/DurerAngelApocalypse.15.4.bqscan.png)