article

begin page 172 | ↑ back to topThe Embattled Sexes: Blake’s Debt to Wollstonecraft in The Four Zoas

Our knowledge of Blake’s acquaintance with the writings of Mary Wollstonecraft is at once precise and frustratingly incomplete. We know he illustrated, and presumably also read, her novel Original Stories from Real Life.1↤ 1 He also illustrated her translation of Salzmann’s Elements of Morality. For the details see David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet against Empire, rev. ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1969), p. 156; Jacob Bronowski, William Blake and the Age of Revolution (1965; rpt. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972), p. 150; and Dennis M. Welch, “Blake’s Response to Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories,” Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 13 (1979), 4-15. We also have evidence in his earlier works, notably in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, that he was influenced by the doctrines she expressed in Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).2↤ 2 These parallels are noted by Mark Schorer, William Blake: The Politics of Vision (1946; rpt. New York: Knopf, 1959), pp. 187 and 251; and Erdman, Blake: Prophet against Empire, p. 243. Moreover, both writers were frequent visitors at the bookseller and publisher Joseph Johnson in the early 1790s; and would, at the very least, have been known to each through word of mouth. But here the incidents of explicit contact cease.3↤ 3 Commentators, however, have offered a range of conflicting, speculative readings in an attempt to enlarge this meagre fund of biographical information. In “Notes on the Visions of the Daughters of Albion by William Blake,” Modern Language Quarterly 9 (1948), 292-97, for instance, Henry H. Wasser argues that Visions is, on one level, “an expression of Blake’s knowledge of the love affair between Mary Wollstonecraft and Henry Fuseli” (p. 292). But Kathleen Raine, in Blake and Tradition (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969), I, 166-68, proposes that elements of the work may reflect a passionate attachment between Blake and Wollstonecraft, while Morton D. Paley claims that “the story of Oothoon and Bromion reflects that of Mary Wollstonecraft and her American lover Gilbert Imlay, with at least a possibility that Blake cast himself as Theotormon” (William Blake [Oxford: Phaidon, 1978], p. 27). On 8 December 1792 Wollstonecraft left for France, where she was to witness the progress of revolution at first hand. Blake’s domicile remained England, and there is nothing to indicate that they met after her return to London in 1795. Yet Wollstonecraft’s ideas would continue to act as a catalyst in his protracted exploration of embattled sexuality, long after all personal ties between them had been severed.

The possibility of her continued influence on Blake’s work, however, has been partially obscured by the illuminated books printed between 1793 and 1795. In these, the emphasis is primarily sociopolitical; and personae often seem more suited to illuminating the larger historical forces at work in the poet’s time than the intricate relationship of the sexes.4↤ 4 There are obviously exceptions to these broad generalizations. The Book of Urizen, for instance, presents a cosmic myth, and the Los-Enitharmon-Orc triad portrays recognizable human archetypes, although the overwhelming preoccupation of the Lambeth books is with the revolutionary forces manifested in Blake’s time. For the historical background informing these works see Blake: Prophet against Empire, pp. 201-79; Morton D. Paley, Energy and the Imagination: A Study of the Development of Blake’s Thought (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970), pp. 61-88; and Michael J. Tolley, “Europe: ‘to those ychain’d in sleep,’ ” in Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic, ed. David V. Erdman and John E. Grant (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1970), pp. 115-45. In particular, the female figure becomes the subject of vast and frequently negative metaphorical expansion, as in Europe a Prophecy. There Enitharmon and her daughters can variously represent the all-consuming Female Will, the vegetative world, and the benighted social, moral and religious constructs of man’s fallen consciousness. Hence discussions of Blake’s debt to Wollstonecraft tend to focus exclusively on Visions of the Daughters of Albion, where the basic situation, despite its wider sociohistorical implications, is that of a lovers’ triangle; and where the heroine Oothoon offers, in word and deed, a Blakean version of major dilemmas articulated in Vindication of the Rights of Woman. But, as I hope to demonstrate, Blake’s debt to Wollstonecraft’s Vindication does not cease there. Instead, his complex treatment of women in the ensuing Lambeth books is closely related to Oothoon’s views, and with them to Wollstonecraft’s conception of female potential. Moreover, these ideas are further developed in The Four Zoas, where many crucial conceptual links between the works of Blake and Wollstonecraft testify to the enduring impact on him of her impassioned call for harmony, equality and true friendship between the sexes.

Visions of the Daughters of Albion offers evidence not only of Blake’s debt to Wollstonecraft but, more importantly, of his capacity to assimilate her ideas into his evolving cosmology. As commentators have noted, Oothoon’s description of the negative and positive roles open to her sex seems to draw heavily on the Vindication.5↤ 5 Other issues, of course, inform her speeches, most notably the contemporary debate on slavery. For the details see David V. Erdman, “Blake’s Vision of Slavery,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 15 (1952), 242-52, or Blake: Prophet against Empire, pp. 226-42. In essence, her speeches contrast the prevailing feminine mode of “hypocrite modesty,” which transforms love into a possession and the sexes into ravening beasts, with the female’s potential to redeem herself and her surroundings through freely given love: ↤ 6 All references to Blake are from E: The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, 4th printing, rev. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1970), and K: The Complete Writings of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes, 3rd printing, rev. (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1971), using the following abbreviations: VDA: Visions of the Daughters of Albion; L: The Book of Los; E: Europe a Prophecy; A: The Book of Ahania; FZ: The Four Zoas.

Open to joy and to delight where ever beauty appearsBut while Visions and the Vindication are remarkably similar in their critique of debilitating sexual roles, a clear distinction needs to be made between their characterizations of liberated woman. Wollstonecraft’s ideal woman approximates, not Oothoon, but the chaste and disciplined Jane Eyre, whom Charlotte Bronte presents as the equal and devoted companion of her husband. In the Vindication monogamy is commended; and the way to emancipation is sought in equal access to education, rather than in what, to Urizenic eyes, must seem Oothoon’s advocacy of universal promiscuity.

If in the morning sun I find it: there my eyes are fix’d

In happy copulation; if in the evening mild, wearied with work;

Sit on a bank and draw the pleasures of this free born joy.

(VDA 6:22-23, 7:1-2, E49/K194)6

These conservative views, which tend to separate and repress basic human needs, are ruthlessly

exposed in Visions of the Daughters of Albion. There education is inherently

sexual,7↤ 7 Or as Paley says of The Marriage of Heaven and

Hell, “Blake envisions, not revolution and sexual freedom, but a revolution which is

libidinal in nature” (Energy and the Imagination, p. 16). and one measure of devoted

and unselfish companionship is willing complicity in the total sexual freedom of one’s partner:

↤ 8 In their immediate context, the lines refer only to plural partners for

the male, but Oothoon’s earlier comments on the crippling effects of enforced monogamy seem to project an

ideal of equal freedom for both the male and the female. Similarly, Blake’s contemporary comments in the

Notebook repeatedly recognize the equal and complementary needs of the sexes, as in the following lines, where

the emphatic parallelism negates any possibility of sexist distinctions:

What is it men in women do require

The lineaments of Gratified Desire

What is it women do in men require

The lineaments of Gratified Desire

(E466/K180)

Failure to recognize this larger context, however, can almost transform the healthy Oothoon into a sexual

deviant, as when Leopold Damrosch, Jr., speaks confidently of her “fantasies, with their sadomasochism and

voyeurism” in Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1980),

p. 198.

But silken nets and traps of adamant will Oothoon spread,In the Vindication, Wollstonecraft’s apparent neglect of woman’s sexuality is, of course, in part a reaction against the enforced role of the female as a mere instrument for man’s sensual gratification.9↤ 9 Alternatively, given the unusual degree of sexual liberation she was to enjoy in her own life, this omission may reflect a conscious concession to her audience, made in the hope of winning approval for other radical and, in some senses, more important aspects of her program for female emancipation. She thus attacks passionate, physical love as a force which must, and can be, mastered early in a relationship: “a master and mistress of a family ought not to continue to love each other with passion. . . . they ought not to indulge those emotions which disturb the order of society, and engross the thoughts that should be otherwise employed.”10↤ 10 Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects, ed. Carol H. Poston (New York: Norton, 1975), pp. 30-31. Future page references to this edition will be cited parenthetically. According to her, “love, perhaps, the most evanescent of all passions, gives place to jealousy or vanity” (p. 27); and its unreasonable deification is seen as a major cause of woman’s, and more generally mankind’s, wretched lot. Blake, characteristically, was able to acknowledge and transcend the partial truth embodied in this view. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion perversions do indeed result from such a limited notion of love, but libidinal energy is also presented

And catch for thee girls of mild silver, or of furious gold;

I’ll lie beside thee on a bank & view their wanton play

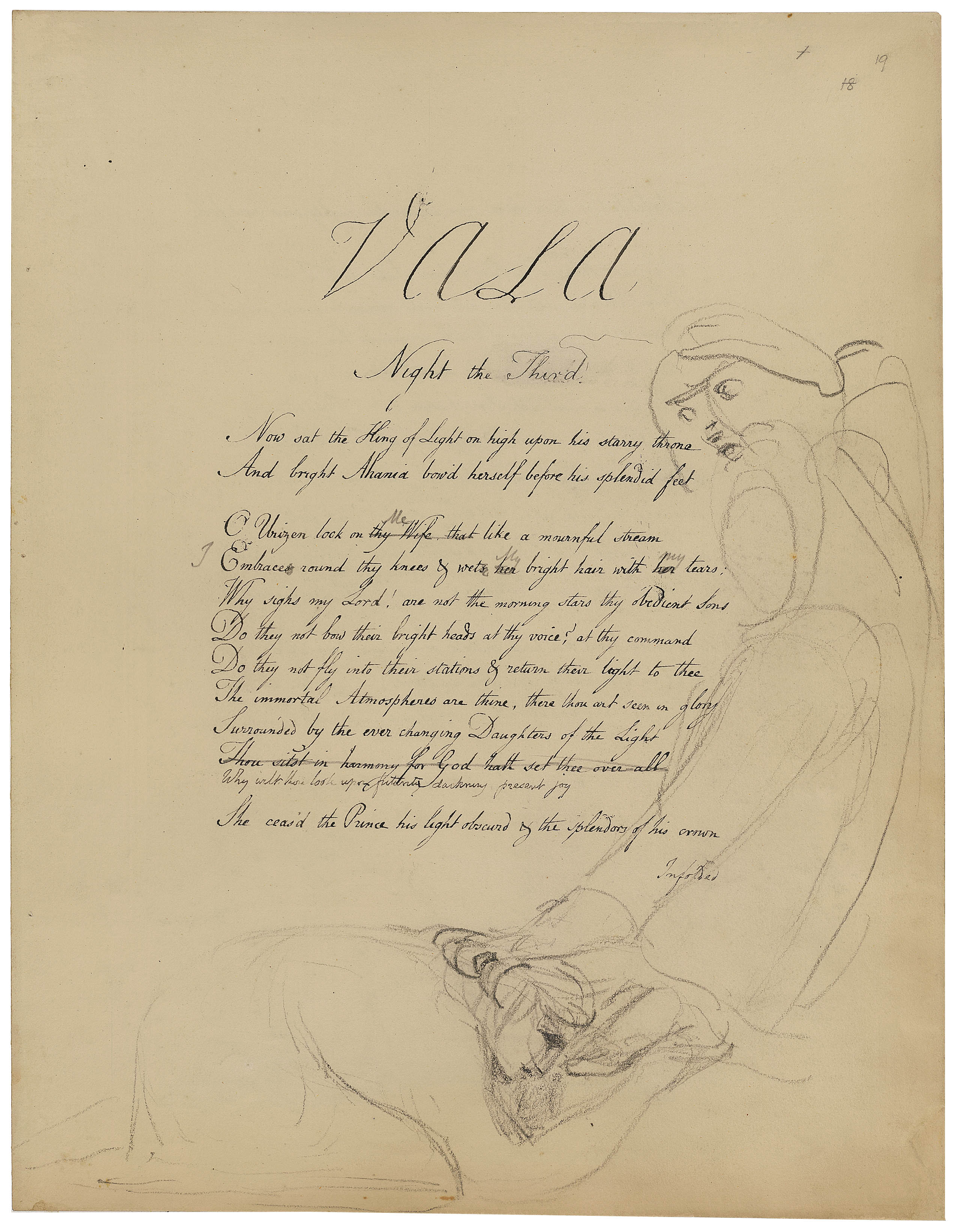

begin page 173 | ↑ back to topIn lovely copulation bliss on bliss with Theotormon:1. Visions of the Daughters of Albion, copy A, pl. 3. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Red as the rosy morning, lustful as the first born beam,

Oothoon shall view his dear delight, nor e’er with jealous cloud

Come in the heavens of generous love; nor selfish blightings bring.

(VDA 7:23-29, E49/K194-95)8

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Throughout the Lambeth period, Blake’s appraisal of female capabilities remains constant, although their presentation varies according to the scope and aim of the specific work. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion the influence of Wollstonecraft is most apparent, because this work, like her own Vindication of the Rights of Woman, focuses on the perverted relationships generated by restrictive social conditioning. The ensuing Lambeth books, however, are more concerned with developing a coherent cosmology and with exploring the negative effects of mankind’s fall. Consequently, the identification of woman with the memory or latent promise of visionary renewal is subordinate to her projection as an active participant in the “torments of love and begin page 174 | ↑ back to top

jealousy.” In these works, she is associated overwhelmingly with dominion and selfish love or, more alarmingly, with the fall into generative division;11↤ 11 This is as true of America a Prophecy as it is of other works of the period, like Europe a Prophecy and The Book of Urizen. For as Minna Doskow has demonstrated in “William Blake’s America: The Story of a Revolution Betrayed,” Blake Studies 8 (1979), 167-86, the shadowy female of the preludium acts the part of “the obedient daughter of a tyrannical father” (p. 171). She is used as an instrument to enslave the dangerous energies of Orc; and when this strategy fails her long training ensures that the love she returns the fiery youth is selfish and possessive, and that revolutionary potential is thereby severely limited. and so with the last stage in that benighted state of consciousness which separates man from his original unity and divinity.12↤ 12 In fact, the negative impression left by these works has been so strong that Susan Fox has felt compelled to argue against the received view of Oothoon. According to her reading, Blake’s choice of a woman as the main protagonist in Visions reflects, not even a relenting in his view of womankind, but rather his need for a figure who could be symbolically raped and readily enslaved (“The Female as Metaphor in William Blake’s Poetry,” Critical Inquiry 3 [1977], 513). A more persuasive and illuminating commentary on this issue, however, is provided by Irene Taylor, “The Woman Scaly,” Bulletin of the Midwest Modern Language Association 6 (1973), rpt. in Mary Lynn Johnson and John E. Grant, eds., Blake’s Poetry and Designs (New York: Norton, 1979), pp. 539-53. There we are invited to see Blake’s critical treatment of womankind as “reflecting a view prominent in Western mythologies” (p. 542), rather than a personal animus.Counterpointing these harsh associations, however, is the awareness that woman, no less than man, can maintain “the Divine Vision in time of trouble.” In The Book of Los, for instance, Blake foreshadows the regenerative role of Enion in The Four Zoas, when he attributes to “Eno aged Mother” the opening lament, which juxtaposes the world of Experience with “Times remote! / When Love & Joy were adoration” (L 3:7-8, E89/K256). Even in Europe a Prophecy, the predatory Enitharmon, at the height of her power, is forced to acknowledge the existence of an antithetical code of female behavior:

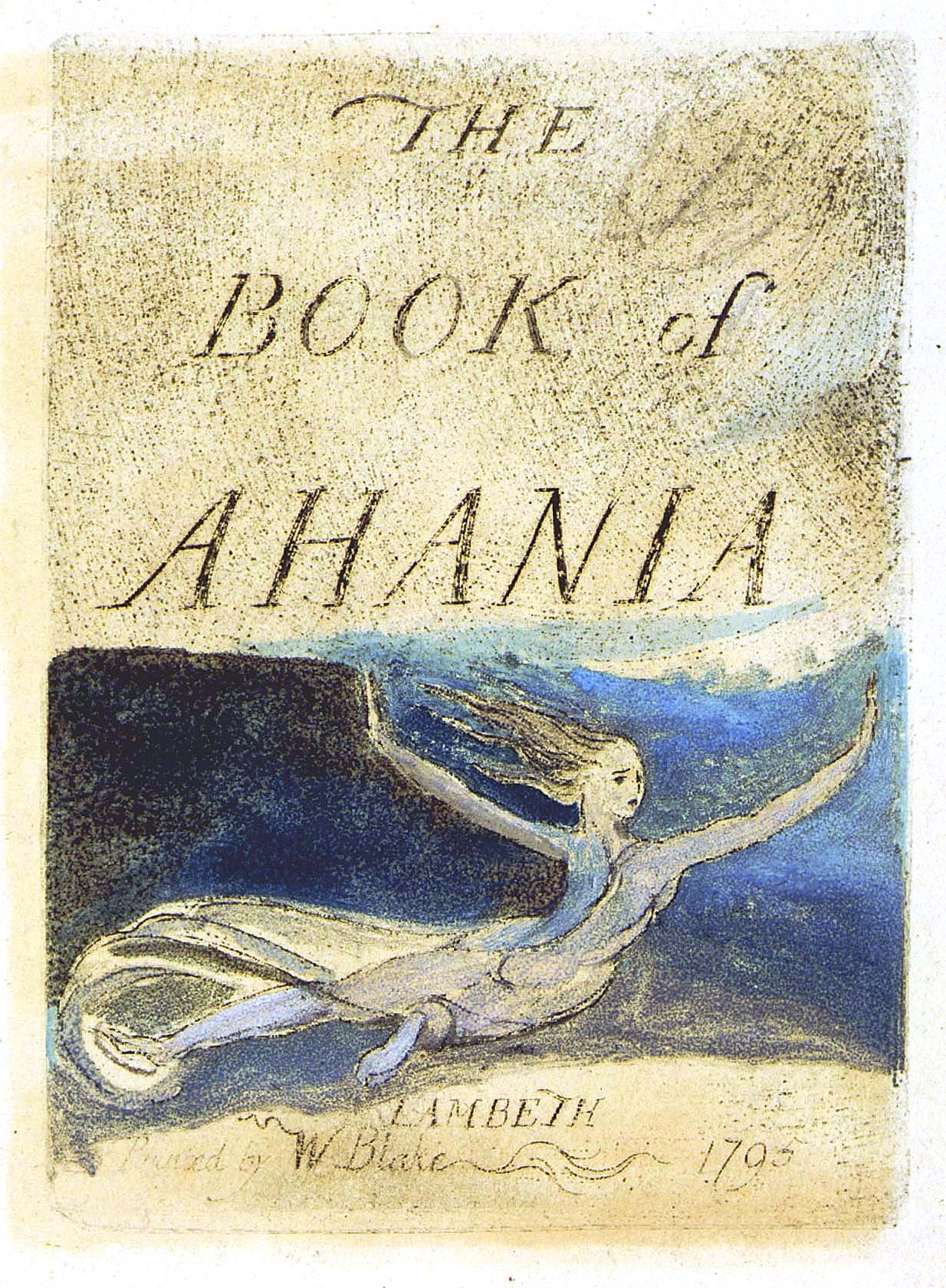

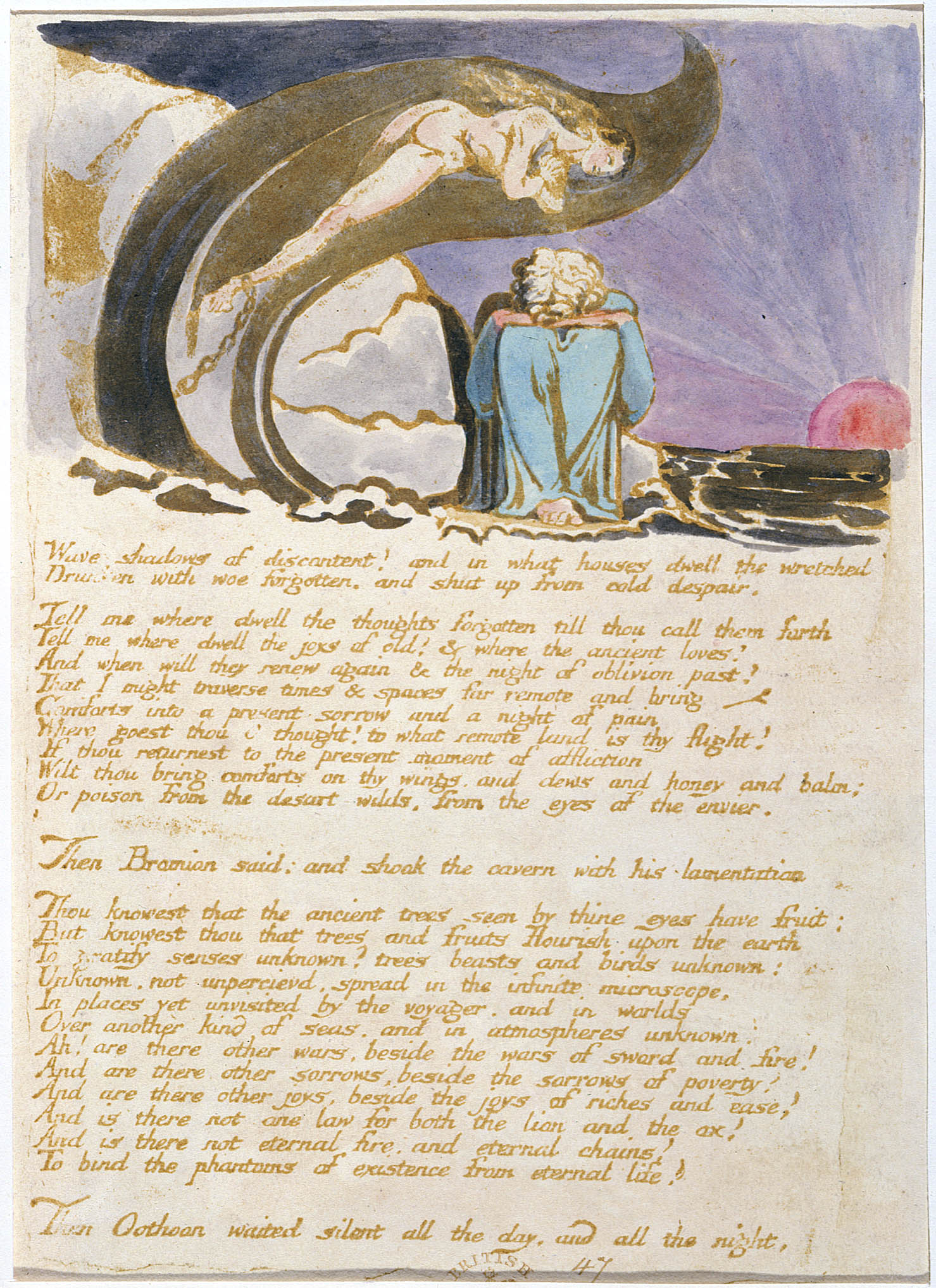

I hear the soft Oothoon in Enitharmons tents:But the most striking evidence for the continuity of Blake’s conception of the female is provided by The Book of Ahania. Printed two years after Visions and probably little more than a year before he began work on Vala,13↤ 13 The most comprehensive and informed discussions of putative composition dates and textual details are to be found in William Blake, Vala or The Four Zoas: A Facsimile of the Poem and A Study of Its Growth and Significance, ed. G. E. Bentley, Jr. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963); David V. Erdman, “The Binding (et cetera) of Vala,” The Library 29 (1969), 112-29; The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, pp. 737-39; and in Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 12 (Fall 1978), an issue devoted to The Four Zoas. it portrays man as jealous and vengeful in the figures of Fuzon and Urizen; whereas Oothoon-like woman is made the advocate of genuine love and forgiveness. The frontispiece presents Ahania cowering and surrounded by a squatting male figure. Her rather phallic posture, between his spread legs, suggests both her birth from Urizen’s shattered loins and her relegation to a limited sexual role by the male. Yet although perverted man will call her Sin and establish her as a fetish for secret worship, the title-page illustration of solitary, flying Ahania implies the presence of a distinctive personage beyond the bounds of restricting, Urizenic perception.14↤ 14 Despite her somewhat ambiguous gestures and posture, I assume that she is flying because, as David V. Erdman notes, the depiction of her hair “indicates swift flight” (The Illuminated Blake [London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1975], p. 211). This promise she fulfills in her concluding lament over the fallen Urizen, which recalls Oothoon’s memories of fulfilling love and anticipates a similar plaint by Ahania in Night the Third of The Four Zoas: ↤ 15 Her concluding words also echo lines eleven to fifteen of “Earth’s Answer,” Selfish father of men

Why wilt thou give up womans secrecy my melancholy child?

(E 14:21-22, E64/K244)

Cruel jealous selfish fear

Can delight

Chain’d in night

The virgins of youth and morning bear, and thereby link her with the life-and love-giving attributes of the female Earth. For a full discussion of these implications, and of Blake’s association of the female figure with apocalyptic renewal in “The Little Girl Lost” and “The Little Girl Found,” see my essay “Blake’s Problematic Touchstones to Experience: ‘Introduction,’ ‘Earth’s Answer,’ and the Lyca Poems,” Studies in Romanticism 19 (1980) 3-17.

Then thou with thy lap full of seedIn the works printed between Visions and Vala, then, Blake divided among separate personae elements of the Wollstonecraftian vision first attributed to Oothoon. This enabled a more flexible and clearly differentiated treatment of female potential, well suited to his wider examination of myth, history, and psychological motivation. The division also prepared the way for that dialectical interplay between positive and negative forces which, in The Four Zoas, is a prelude to apocalypse.

With thy hand full of generous fire

Walked forth from the clouds of morning

On the virgins of springing joy,

On the human soul to cast

The seed of eternal science.

. . . . . .

But now alone over rocks, mountains

Cast out from thy lovely bosom:

Cruel jealousy! selfish fear!

begin page 175 | ↑ back to top Self-destroying: how can delight,

Renew in these chains of darkness

Where bones of beasts are strown

On the bleak and snowy mountains

Where bones from the birth are buried

Before they see the light.

(A 5:29-34, 39-47, E88-89/K255)15

By the time Blake began Vala, Wollstonecraft’s ideas had thus been thoroughly absorbed into his developing cosmology. Consequently, the full and lasting extent of her influence shows itself not in direct echoes or explicit allusions, but in broad and significant areas of conceptual agreement, such as the close resemblance of Blake’s characterization of the delusive emanation to the portrayal of woman’s severely circumscribed state in the Vindication.16↤ 16 Some of these female traits had, of course, appeared in earlier works, such as Europe a Prophecy. But it is not until The Four Zoas that they receive detailed treatment; and only then does their close association with Wollstonecraft’s conceptions clearly emerge. Wollstonecraft, positing that woman has the same rational potential as man, claims that she receives a limiting education in accordance with the subordinate role attributed to her in a male-dominated world. She is taught to be pleasant and alluring; her single goal is to attract, capture, and then retain a male because, given her lack of any wider education, she is inevitably dependent on males for her sustenance. As a result women are encouraged, either implicitly or explicitly, to be charming, vain, proud, jealous, indolent and, above all, cunning: “that pitiful cunning which disgracefully characterizes the female mind—and I fear will ever characterize it whilst women remain the slaves of power!” (p. 164). Their social and physical weakness leaves them no option but to use their few native weapons, such as beauty, tears and smiles, to overcome their legal oppressors. The result is an undeclared but constant battle between the sexes for command, or as Wollstonecraft explains: “It is this separate interest—this insidious state of warfare, that undermines morality, and divides mankind!” (p. 97). Similarly in The Four Zoas, as in earlier works, Blake uses the interaction of the sexes to demonstrate both the fallen, divided state of the original Divine Humanity, and the resulting distortion of all moral principles. Furthermore, his emanations correspond almost point by point with Wollstonecraft’s image of perverted

begin page 176 | ↑ back to top womanhood. They too are portrayed as cunning, alluring, unproductive, and involved in an ongoing struggle for and against domination, as in the following passage:Thus sang the Lovely one in Rapturous delusive tranceAnd both writers are equally forthright in condemning those who provide instruction in these female arts. Wollstonecraft for instance, in a chapter entitled “Animadversions on Some of the Writers Who Have Rendered Women Objects of Pity, Bordering on Contempt,” pillories books that advise the alternate use of chastity and coquetry,17↤ 17 Wollstonecraft attacks, for example, the following passage cited from Rousseau: “ ‘Would you have your husband constantly at your feet? keep him at some distance from your person. You will long maintain the authority in love, if you know but how to render your favours rare and valuable. It is thus you may employ even the arts of coquetry in the service of virtue, and those of love in that of reason.’ ” (p. 89). much as Blake disapprovingly quotes Enitharmon’s advice on ways to manipulate parents:

Los heard reviving he siezd her in his arms delusive hopes

Kindling She led him into Shadows & thence fled outstretchd

Upon the immense like a bright rainbow weeping & smiling & fading

(FZ 34:93-96, E318/K290)

To make us happy let them weary their immortal powersAlthough addressed to Los, this speech provides a succinct recipe for female domination, as it is practiced by Vala and Enitharmon herself.18↤ 18 For a fuller account of this, and of other scenes mentioned briefly in this paper, consult Brian Wilkie and Mary Lynn Johnson, Blake’s Four Zoas: The Design of a Dream (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1978). Yet the immediate context of her remarks reminds us that these feminine wiles are not restricted to the emanations alone. Instead, they operate in the fallen world wherever “selfish loves increase”: a point underscored by the accompanying design on page 9 of exhausted Enion, hopelessly pursuing her taunting, ungrateful children.

While we draw in their sweet delights while we return them scorn

On scorn to feed our discontent; for if we grateful prove

They will withhold sweet love, whose food is thorns & bitter roots.

(FZ 10:3-6, E301/K271)

Common also to The Four Zoas and to the Vindication is their

critique of conventional notions of love as a form of self-idolatry, and as a means by which woman obtains

excessive sway. Like Blake, Wollstonecraft argues that man mistakes the shadow for the substance (p. 135), the

ephemeral for the true goals of life: “I see the sons and daughters of men pursuing shadows, and anxiously

wasting their powers to feed passions which have no adequate object” (p. 110). This erroneous condition is,

for both, exemplified by love: “And love! What diverting scenes would it produce—Pantaloon’s tricks must

yield to more egregious folly. To see a mortal adorn an object with imaginary charms, and then fall down and

worship the idol which he had himself set up—how ridiculous!” (p. 111). According to Wollstonecraft,

man’s cherished image of the female emanates from his own fallen consciousness. He then seeks to impose his

projections on women through education (“Why must the female mind be tainted by coquetish arts to gratify

the sensualist . . .?” [p. 31]), and finally falls “prostrate before their personal charms” (p. 92). The

course of fallen love is similarly self-fulfilling in The Four Zoas, although here the

critique of idol-worship encompasses perverted passion in its sexual and religious manifestations. Hence

Albion succumbs to Vala and, even more abjectly, to his own projected divinity:

↤ 19 A parallel image of man’s

idolatry to his female self-projection emerges from the combined accounts of the Spectre of Urthona and the

Shadow of Enitharmon in Night the Seventh (a):

Listen O vision of Delight One dread morn of goary blood

The manhood was divided for the gentle passions making way

Thro the infinite labyrinths of the heart & thro the nostrils issuing

In odorous stupefaction stood before the Eyes of Man

A female bright. . . .

(FZ 84:12-16, E352/K327)

Among the Flowers of Beulah walkd the Eternal Man & Saw

Vala the lilly of the desart. melting in high noon

Upon her bosom in sweet bliss he fainted Wonder siezd

All heaven they saw him dark. . . .

(FZ 83:7-10, E351/K326)

Then Man ascended mourning into the splendors of his palaceThat the Vindication fails to draw this parallel between debased love and worship is perhaps another reflection of Wollstonecraft’s conservatism. But it does not impede her radical vision of passion as an insidious form of self-gratification that leads the sexes further away from an ideal of mutually enhancing unity; and that produces a situation in which women, as Wollstonecraft contends, “indirectly . . . obtain too much power, and are debased by their exertions to obtain illicit sway” (p. 167).

Above him rose a Shadow from his wearied intellect

Of living gold, pure, perfect, holy; in white linen pure he hover’d

A sweet entrancing self delusion, a watry vision of Man

Soft exulting in existence all the Man absorbing

Man fell upon his face prostrate before the watry shadow

Saying O Lord whence is this change thou knowest I am nothing.19

(FZ 40:2-8, E320/K293)

Similarly Blake, throughout The Four Zoas, stresses the elements of narcissism

and tyranny latent in sexual love. Ahania, for instance, in text and design, is shown in acts of abasement at

the feet of the tyrant Urizen; while the interrelationship of sexual and religious idolatry is demonstrated

with brutal frankness on page 44 by a sketch in which the female genitalia are pictured literally as an altar

for secret worship.20↤ 20 Interestingly, Blake and

Wollstonecraft diverge in their views on the effects of solitary withdrawal and reflection. According to

Wollstonecraft, both are necessary if women are to develop independent thought and genuine feeling, or as she

puts it: “Besides, by living more with each other, and being seldom absolutely alone, they [women] are more

under the influence of sentiments than passions. Solitude and reflection are necessary to give to wishes the

force of passions, and to enable the imagination to enlarge the object, and make it the most desirable” (p.

58). In Blake, such acts are often associated with Urizenic withdrawal from humanity, or with negative

self-enjoyings, like those lamented by Oothoon:

The moment of desire! the moment of desire! The virgin

That pines for man; shall awaken her womb to enormous joys

In the secret shadows of her chamber, the youth shut up from

The lustful joy. shall forget to generate. & create an amorous image

In the shadows of his curtains and in the folds of his silent pillow.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Is it because acts are not lovely, that thou seekest solitude.

Where the horrible darkness is impressed with reflections of desire.

(VDA 7:3-7, 10-11, E49/K194)

But where

Wollstonecraft offers only a fragmentary account of the harmful ascendency of debased sexuality, Blake reveals

it behind all humanity’s successive falls. Thus Ahania argues that man’s original error was the result of

his being “Idolatrous to his own Shadow” (FZ 40:12, E321/K293), and the spectre of

Urthona describes his own fall in terms of a division confirmed through self-copulation:

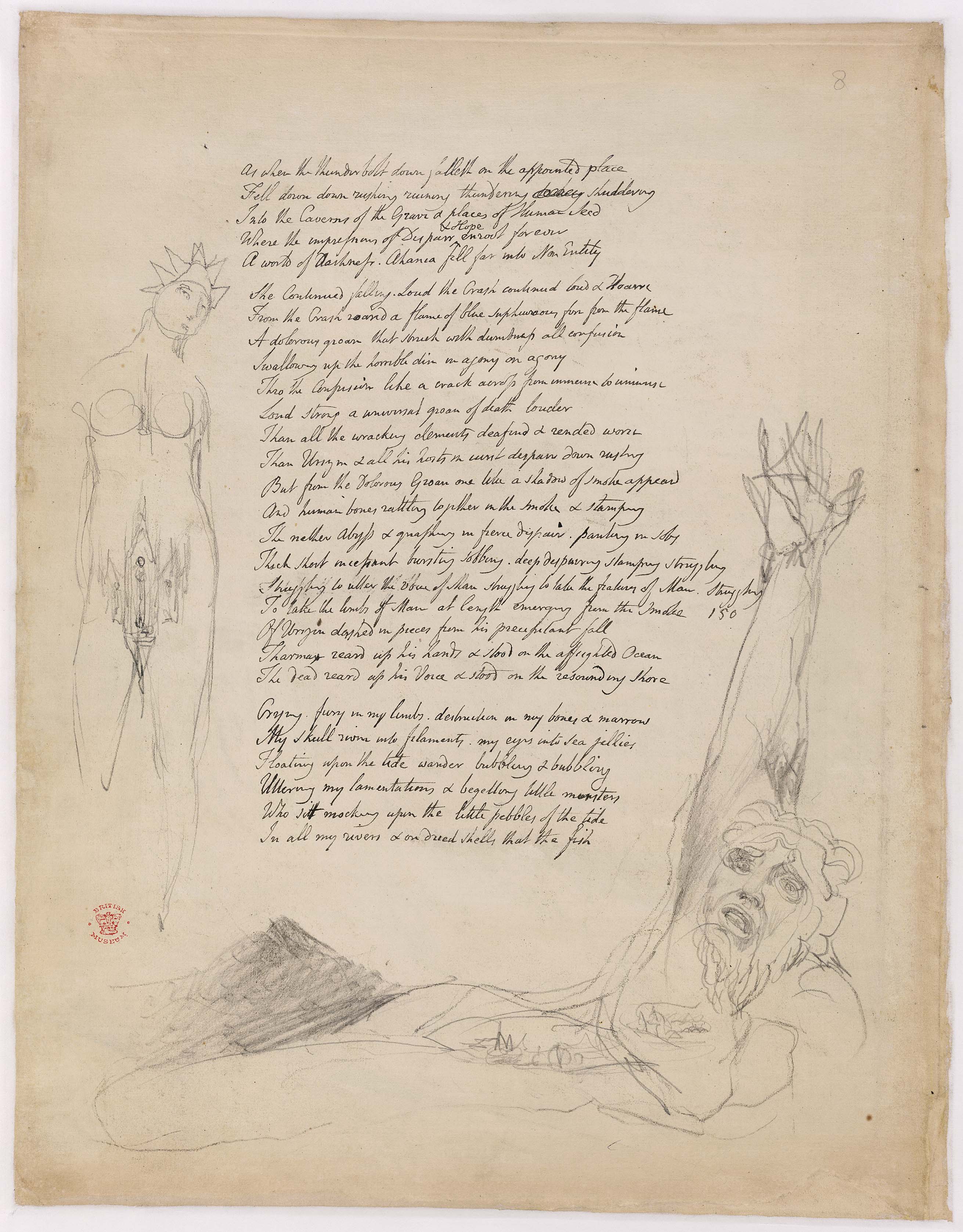

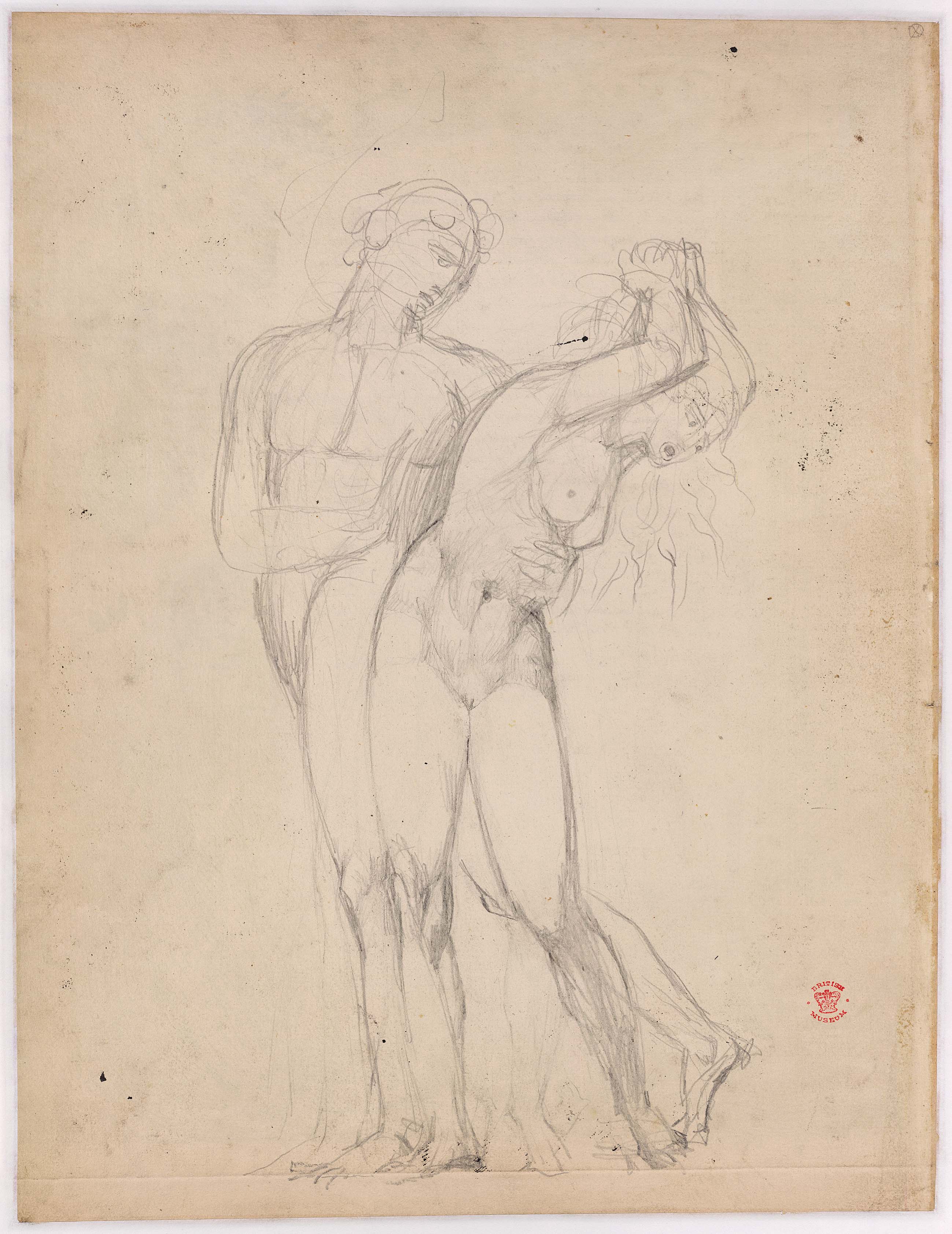

My loins begin to break forth into veiny pipes & writheFallen love is associated here with an emanation projected from and designated by the male, while the expression “My counter part” emphasizes her dual function as a constituent of Urthona and as an inherent property which will hinder a return to his unfallen state. Moreover Wollstonecraft only asserts that these narcissistic relationships are mutually debilitating, whereas Blake continually demonstrates it, as in Night the Third. The opening design on page 37 shows begin page 177 | ↑ back to top Ahania playing the part of a submissive slave, while Urizen’s posture and countenance express revulsion.21↤ 21 The heavily drawn claw on his foot is eloquent testimony both to Urizen’s status as tyrant and to its bestializing[e] effects: a theme repeated in other Blake designs, such as those of Nebuchadnezzar. The implications of this scene are articulated later, when Urizen chastizes Ahania for the perfect obedience which he himself demanded, because he perceives his loathsome self-image in the undistorting mirror she affords:

Before me in the wind englobing trembling with strong vibrations

The bloody mass began to animate. I bending over

Wept bitter tears incessant. Still beholding how the piteous form

Dividing & dividing from my loins a weak & piteous

Soft cloud of snow a female pale & weak I soft embracd

My counter part & calld it Love I named her Enitharmon.

(FZ 50:11-17, E327/K300)

Thou little diminutive portion that darst be a counterpartBy trying to become more than man he too has become less or diminutive. Her “laws” are those he promulgates and, with the confusion typical of fallen reason, the former image of her that he lovingly invokes has the characteristics for which he now curses her. Furthermore, because these attributes are, as he recognizes, dominant in himself, any attempt to reject them in her can precipitate his own fall. So Blake, with fine dramatic irony, makes Urizen the judge and destroyer of his own realm. For at this stage the tyrant has only glimmerings of what will become redemptive self-consciousness in Night the Ninth, much as his precipitation to lower depths ironically foreshadows the lesson of self-abnegation he has yet to learn before true regeneration can begin. Here undeniably, as in other scenes, Blake’s attack on “selfish loves” is more specific and coherent than Wollstonecraft’s. But his basic views certainly accord with the details of her discussion, and with her summary conclusion that man must “willingly resign the privileges of rank and sex for the privileges of humanity” (p. 149).

They passivity thy laws of obedience & insincerity

Are my abhorrence. Wherefore hast thou taken that fair form

Whence is this power given to thee! once thou wast in my breast

A sluggish current of dim waters. on whose verdant margin

A cavern shaggd with horrid shades. dark cool & deadly. where

I laid my head in the hot noon after the broken clods

Had wearied me. there I laid my plow & there my horses fed

And thou hast risen with thy moist locks into a watry image

Reflecting all my indolence my weakness & my death

(FZ 43:9-18, E322/K295)

Even more important, Blake and Wollstonecraft concur in their analysis of the wider implications of these fallen passions. Apart from transforming what should be “sports of Glory” into those of Cruelty, this debased concept of love destroys the possibility of a healthy parental bond, and is ultimately linked with deleterious social manifestations. In her brief chapter “Parental Affection,” Wollstonecraft remarks that the parent-child bond is often “a pretext to tyrannize where it can be done with impunity” (pp. 150-51). As such, it becomes, “perhaps, the blindest modification of perverse self-love” (p. 150), and can serve as a

begin page 178 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

In The Four Zoas, Blake projects similar insights through the actions of Los and Enitharmon, who appear first as children and then as parents. In their role as parents, they illustrate the perverse self-love and tyrannical drive for unconditional obedience that Wollstonecraft castigates. But Blake’s analysis demonstrates more clearly than the Vindication’s that these egotistical acts recoil harmfully upon their instigators. Los, although he attempts to render “assurance doubly sure” by binding Orc with the chain of jealousy, is himself a victim of the same chain.23↤ 23 Diana Hume George in Blake and Freud (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1980) offers a detailed account of Blake’s exploration of this reciprocal bondage, and of its psychological roots, in a subsection of her study entitled “Experience: The Family Romance” (pp. 98-124). It constricts his vital humanity, and even the removal of its physical presence is no guarantee of complete liberation:

But when returnd to Golgonooza Los & EnitharmonBlake is here contrasting the first glimmerings of genuine, self-sacrificing parental feeling with their destructive opposite: “Love of Parent Storgous Appetite Craving” (FZ 61:10, E334/K308). The dilemma faced by parents and child is analogous[e] to that confronting fallen man and woman. They are doomed to feed selfishly on each other, as do Los and Enitharmon on their mother Enion in Night the First,24↤ 24 Drawing forth drooping mothers pity drooping mothers sorrow

Felt all the sorrow Parents feel. they wept toward one another

And Los repented that he had chaind Orc upon the mountain

And Enitharmons tears prevaild parental love returnd

Tho terrible his dread of that infernal chain . . .

(FZ 62:9-13, E335/K309)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And then they wanderd far away she sought for them in vain

In weeping blindness stumbling she followd them oer rocks & mountains

Rehumanizing from the Spectre in pangs of maternal love

Ingrate they wanderd scorning her drawing her Spectrous Life

Repelling her away & away by a dread repulsive power

Into Non Entity revolving round in dark despair.

And drawing in the Spectrous life in pride and haughty joy

Thus Enion gave them all her spectrous life

(FZ 8:7, 9:1-8, E300/K269-70) or to live in mutual fear and antagonism, until suffering awakens their repressed sense of human sympathy. In a realm where hatred is dominant instead of love, “stern demands of Right & Duty instead of Liberty” (FZ 4: 18-19, E297/K265), the chain of jealousy is justifiably described as “living” and taking root in the earth’s center (FZ 63: 1-4, E336/K308). Los feels its pull. He “dreads” these forces at work within himself and throughout fallen nature. Furthermore, like Enion “Rehumanizing . . . in pangs of maternal love” (FZ 9:3, E300/K276), he must learn repentance and that parental “sorrow” which involves recognizing consanguinity with and responsibility for a world external to the self-centered “I.” This shift is already hinted at in the above passage when “they wept toward one another” and in a design on page 112, which apparently portrays Los attempting to assuage Enitharmon’s maternal bereavement.25↤ 25 W.H. Stevenson in The Poems of William Blake (London: Longman, 1971), p. 428, makes this identification, although Bentley suggests that the leaf on which the drawing occurs originally concluded Night the Fourth (Vala or The Four Zoas, p. 201). In this case the design would illustrate Enitharmon’s response to the binding of Urizen in Night the Fourth. Yet the depiction of Los as at once resolute and tender is closer to the visual description of Los in Night the Fifth than to that in Night the Fourth where Spasms siezd his muscular fibres writhing to & fro his pallid lips

Unwilling movd as Urizen howld his loins wavd like the sea

At Enitharmons shriek his knees each other smote & then he lookd

With stony Eyes on Urizen & then swift writhd his neck

(FZ 55:24-27, E331/K305) By transposing the design to page 112 of Night the Eighth, Blake made possible, and even desirable, Stevenson’s reading. For a visual reference back to events in Night the Fifth is appropriate here, as it reminds us of the starting-point of Los and Enitharmon’s regeneration, which leads to their redemptive labors described on page 113 of Night the Eighth. The binding of Orc occasions then, in Wollstonecraft’s words, “a mutual care [which] produces a new mutual sympathy”; and this, in the full context of Blake’s epic, marks a first step towards that greater self-annihilation which will be demanded of the scattered Zoas, if they are to regain the lost unity of Eternity.

Although the events in The Four Zoas take place on a cosmological scale far removed from the diurnal world described in the Vindication, the redemptive role that Blake attributes to the emanation also appears to owe much to Wollstonecraft’s vision of liberated female potential. Her constant emphasis is on the need to emancipate woman from a constricting sexual role: to have her recognized as an intellectual and, in the widest sense, a human creature. As she explains, the female “was not created merely to be the solace of man, and the sexual should not destroy the human character” (p. 53). Accordingly, she stresses that “true beauty and grace must arise from the play of the mind” (p. 118). Woman should be taught not to control others but herself (p. 62), to turn her “sensibility into the broad channel of humanity” (pp. 174-75); and so “to participate in the inherent rights of mankind” (p. 175). For in Wollstonecraft’s own words, “the corrupting intercourse . . . between the sexes, is more universally injurious to morality than all the other vices of mankind collectively considered” (p. 192). Thus “mutual affection, supported by mutual respect,” must replace “selfish gratification” (p. 192); modesty becomes a “natural reflection of purity” rather than “only the artful veil of wantonness” (p. 193); and compassion be extended “to every living creature (p. 172). Our choice is between “a REVOLUTION in female manners,” which will have “the most salutary effects tending to improve mankind” (p. 192), and a condition that encourages woman “by the serpentine wrigglings of cunning . . . [to] mount the tree of knowledge, and only acquire sufficient to lead men astray” (p. 173).

The final Nights of The Four Zoas dramatize the potential inherent in these alternate conceptions of woman. In Nights the Seventh and Eighth, Blake portrays the spiritual nadir of man, and takes as his central symbol of this enslavement the Tree of Mystery. Around and through this Tree his personae move in an elaborate series of actions which explicitly allude to Milton’s portrayal of the fall, and to the ensuing transformation of Satan and his hellish legions into serpents. But while Paradise Lost is here the main source, it is possible that some of Blake’s rich reworkings of Milton’s motifs were inspired by Wollstonecraft’s comparison of fallen woman’s striving after fulfillment with a serpentine ascent into the Tree of Knowledge. In Night the Seventh, womankind in its lowest and most abstract state (the Shadow of Enitharmon) is pictured as descending “down the tree of Mystery” (FZ 82:16, E350/K327) to lead astray the spectrous form of Urthona. Following their sexual union, they are found “Conferring times on times among the branches of that Tree” (FZ 85:4, E353/K327). In Night the Eighth, this same constellation of images is iterated almost obsessively on manuscript pages 101 and 103, as Vala exerts her sway:

Beginning at the tree of Mystery circling its rootFor Blake, this repeated motif presents woman at her most dangerous and debased. In Wollstonecraft’s words, “the sexual” has been allowed to “destroy the human character.”26↤ 26 My comments here are complemented by Jean H. Hagstrum’s section on “the phallic woman” in “Babylon Revisited, or the Story of Luvah and Vala,” in Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on The Four Zoas Milton Jerusalem, ed. Stuart Curran and Joseph Wittreich, Jr. (Madison: Wisconsin Univ. Press, 1973), pp. 108-12, and by John E. Grant’s account of the motif of “erotic degradation,” which appears in Blake’s designs to the poem, in “Visions in Vala: A Consideration of Some Pictures in the Manuscript,” in Blake’s Sublime Allegory, pp. 141-202. Similarly, in drawings on pages 86 and 26, Vala is portrayed both as a sensuous, fecund figure, and as a hideous, hybrid dragon-form. The former captures her alluring presence, begin page 180 | ↑ back to top the latter constitutes a visionary judgment on her role in entrapping man in the toils of corporeality. Yet whether pictured as a gazer fixated on external existence or as an embodiment of pestilential evil, woman and her generative acts can be seen by Blake as potential images or means of regeneration.27↤ 27 The theme is a common one in the later prophecies. Book one of Milton, for instance, concludes with a great hymn on the spiritual wonders of vegetative life, and Los sums up this vision on plate 7 of Jerusalem with the exclamation: “O holy Generation [Image] of regeneration!.” (E149/K626). Her realm is nature, and nature remains part of the Divine Humanity. Hence even the triumph of Vala can serve paradoxically as a prelude to apocalypse, for any consolidation of error makes it more readily identifiable and remediable. Moreover, this dual character of female action, its potential for good and evil, is made explicit through the respective weaving of Enitharmon and Rahab-Tirzah: ↤ 28 The complex significance of this weaving motif is dealt with by Morton D. Paley in “The Figure of the Garment in The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem,” in Blake’s Sublime Allegory, pp. 119-39.

She spread herself thro all the branches in the power of Orc.

(FZ 103:23-24, E361/K345)

Enitharmon wove in tears Singing Songs of LamentationsHere woman is no longer presented as a single and negative aspect of man. Instead she is used in these Nights to embody our complex capacity for creative and uncreative labor, for regeneration or self-damnation; and so she becomes at last the male’s true counterpart in the mental wars of Eternity, as well as in the cruel sports of the fallen realm.

And pitying comfort as she sighd forth on the wind the spectres

And wove them bodies calling them her belovd sons & daughters

(FZ 103:32-34, E361/K345)

While Rahab & Tirzah far different mantles prepare webs of torture

Mantles of despair girdles of bitter compunction shoes of indolence

Veils of ignorance covering from head to feet with a cold web.

(FZ 113:19-21, E362/K346)28

In accordance with this expanded conception of woman, emanations assume the role of moral agents which Wollstonecraft had foreseen for her sex (p. 178). In Night the Second, for instance, Enion utters from the Void one of Blake’s greatest condemnatory songs of Experience; and her words suffuse with concern a fellow emanation, Ahania, who “never from that moment could . . . rest upon her pillow” (FZ 36:19, E319/K291). A succession of suffering spokeswomen is thereby assured, and woman is singled out as a focal point of genuine moral vision. Hence Blake, at the end of Night the Eighth, employs chants by Ahania and Enion, rather than one by Los, to prepare the reader for the ensuing Vintage of the Nations. First Ahania, who “Saw not as yet the Divine vision her Eyes are Toward Urizen” (FZ 108:7, E368/K353), catalogues the intricate mazes of Experience:

Will you seek pleasure from the festering wound or marry for a WifeHere woman and earth assume metaphoric equivalence as referents for that vegetative existence which both nourishes and kills. But in the following chant of Enion, from beyond the limitations of fallen perception, the female earth is subsumed in the Eternal Man:

The ancient Leprosy that the King & Priest may still feast on your decay

And the grave mock & laugh at the plowd field saying

I am the nourisher thou the destroyer in my bosom is milk & wine

And a fountain from my breasts to me come all multitudes

(FZ 108:13-17,E369/K354)

So Man looks out in tree & herb & fish & bird & beastAs in the Vindication, so here lasting harmony is inseparable from the realization of compassion for all things, and from the merging of secondary distinctions in the redemptive vision of a single and indissoluble humanity. This vision becomes reality in Night the Ninth. But instead of Wollstonecraft’s notion of a bloodless revolution having “the most salutary effects tending to improve mankind,” Blake offers a picture of fierce and, at times, anguished transformation. Mankind is literally threshed and crushed free from fallen selfhood. Here the virtues of purity, modesty, and disinterested compassion, espoused by Wollstonecraft, are largely relegated to a “lower Paradise” (FZ 128:30, E382/K369), where the instinctual passions have to relearn their innocence under the guidance of a morally regenerated Vala.29↤ 29 For a more complete account of this scene see Blake’s Four Zoas: The Design of a Dream, pp. 223-28. By implication, Blake suggests that these traditional virtues exist in their pure forms only “in Eternal Childhood,” and he is careful to stress that the protagonists are merely “the shadows of Tharmas & of Enion in Valas world” (FZ 131:19, E385/K371). A clear distinction is thus made between the redemptive role of the female and the role of her conventional attributes. These attributes, at best, are elements in a limited pastoral interlude; while the truly emancipated female plays a more active and vitally engaged role in the ongoing spiritual harvest. Characteristically, Blake’s enlarged concept of human potential allows him to appropriate, and then to develop, progressive ideas from the Vindication; although here, as in his other reworkings of Wollstonecraft, he shows himself capable of transcending the received assumptions that are also embodied in her work.30↤ 30 Blake’s capacity to select only what he needed from Wollstonecraft, and at the same time to criticize her conservative viewpoints, is well illustrated by Dennis M. Welch in “Blake’s Response to Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories.”

Collecting up the scatterd portions of his immortal body

Into the Elemental forms of every thing that grows

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And in the cries of birth & in the groans of death his voice

Is heard throughout the Universe whereever a grass grows

Or a leaf buds The Eternal Man is seen is heard is felt.

(FZ 110:6-8, 25-27, E370/K355-56)

Thus Blake not only found inspiration in Wollstonecraft’s work, but he also succeeded in freeing her perceptions from many of their contemporary limitations. For Vindication of the Rights of Woman, despite its revolutionary fervor, remains partly ensnared by conventional notions of morality, education, and human capacity. Here man, at his noblest, is pictured as a rational creature; literature as peculiarly suited to increase the scope of his reason; and social stability as a necessity for fruitful human intercourse.31↤ 31 Wollstonecraft, of course, was not alone in her failure to transcend many of the reactionary values of her age. Even her husband, the anarchist philosopher William Godwin, was capable of attacking all the institutions of society, and yet of defending the need for material security, in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. But Blake, ignoring this conservatism, focused on the work’s incisive analysis of the conditions generated by debased sexuality, and on its concrete suggestions for their begin page 181 | ↑ back to top amelioration. These notions he had thoroughly assimilated by 1793 at the latest, with the publication of Visions of the Daughters of Albion; and they were then expanded and emended in accordance with the cosmological vision developed in the Lambeth books. For the liberating views expounded in the Vindication required a new conception of art, language and human creativity commensurate with their radical potential. This Blake provided in The Four Zoas, where woman becomes the fallen emanation, self-realization the prelude to apocalypse, mutual affection and forgiveness the Gates of Paradise. There at last Wollstonecraft’s precepts attain the fulfillment denied them in her work and in her tragically brief life; and there also they are saved from the usual fate of truth in this world, which she pictures as “lost in a mist of words, virtue, in forms” (p. 12), by an art form created specifically “for the day of Intellectual Battle” (FZ 3:3, E297/K264).

![5

{7}

{embracd for}

{love}

And then they wanderd far away she sought for them in vain

In weeping blindness stumbling she followd them oer rocks & mountains

Rehumanizing from the Spectre in pangs of maternal love

Ingrate they wanderd scorning her drawing her {life; ingrate} Spectrous Life

Repelling her away & away by a dread repulsive power 100

Into Non Entity revolving round in dark despair.

{Till they had drawn the Spectre quite away from Enion}

And drawing in the Spectrous life in pride and haughty joy

Thus Enion gave them all her spectrous life {in dark despair}

Then {Ona} Eno a daughter of Beulah took a Moment of Time

And drew it out to {twenty years} Seven thousand years with much care & affliction

And many tears & in the {twenty} Every years {gave visions toward heaven} made windows into

Eden

She also took an atom of space & opend its center

Into Infinitude & ornamented it with wondrous art

Astonishd sat her Sisters of Beulah to see her soft affections

To Enion & her children & they ponderd these things wondring

And they Alternate kept watch over the Youthful terrors

They saw not yet the Hand Divine for it was not yet reveald

But they went on in Silent Hope & Feminine repose

But Los & Enitharmon delighted in the Moony spaces of {Ona} Eno

Nine Times they livd among the forests, feeding on sweet fruits

And nine bright Spaces wanderd weaving mazes of delight

Snaring the wild Goats for their milk they eat the flesh of Lambs

A male & female naked & ruddy as the pride of summer

p. 8

Ellis

Alternate Love & Hate his breast; hers Scorn & Jealousy

{They kissd not for shame they embracd not}

In embryon passions. they kiss’d not nor embrac’d for shame & fear 150

{Nor kissd nor em[braced]}

{hand in hand in a Sultry paradise}

{these Lovers swum the deep}

His head beamd light & in his vigorous voice was prophecy

He could controll the times & seasons, & the days & years

She could controll the spaces, regions, desart, flood & forest

But had no power to weave a Veil of covering for her Sins

She drave the Females all away from Los

And Los drave all the Males from her away

They wanderd long, till they sat down upon the margind sea.

Conversing with the visions of Beulah in dark slumberous bliss

Night the Second

{Nine years they view the turning spheres {of Beulah} reading the Visions of Beulah}

But the two youthful wonders wanderd in the world of Tharmas

Thy name is Enitharmon; said the {bright} fierce prophetic boy

{While they} {Harmony}

While thy mild voice fills all these Caverns with sweet harmony

O how {thy} our Parents sit & {weep} mourn in their silent secret bowers](img/illustrations/BB209.1.9.MS.300.jpg)

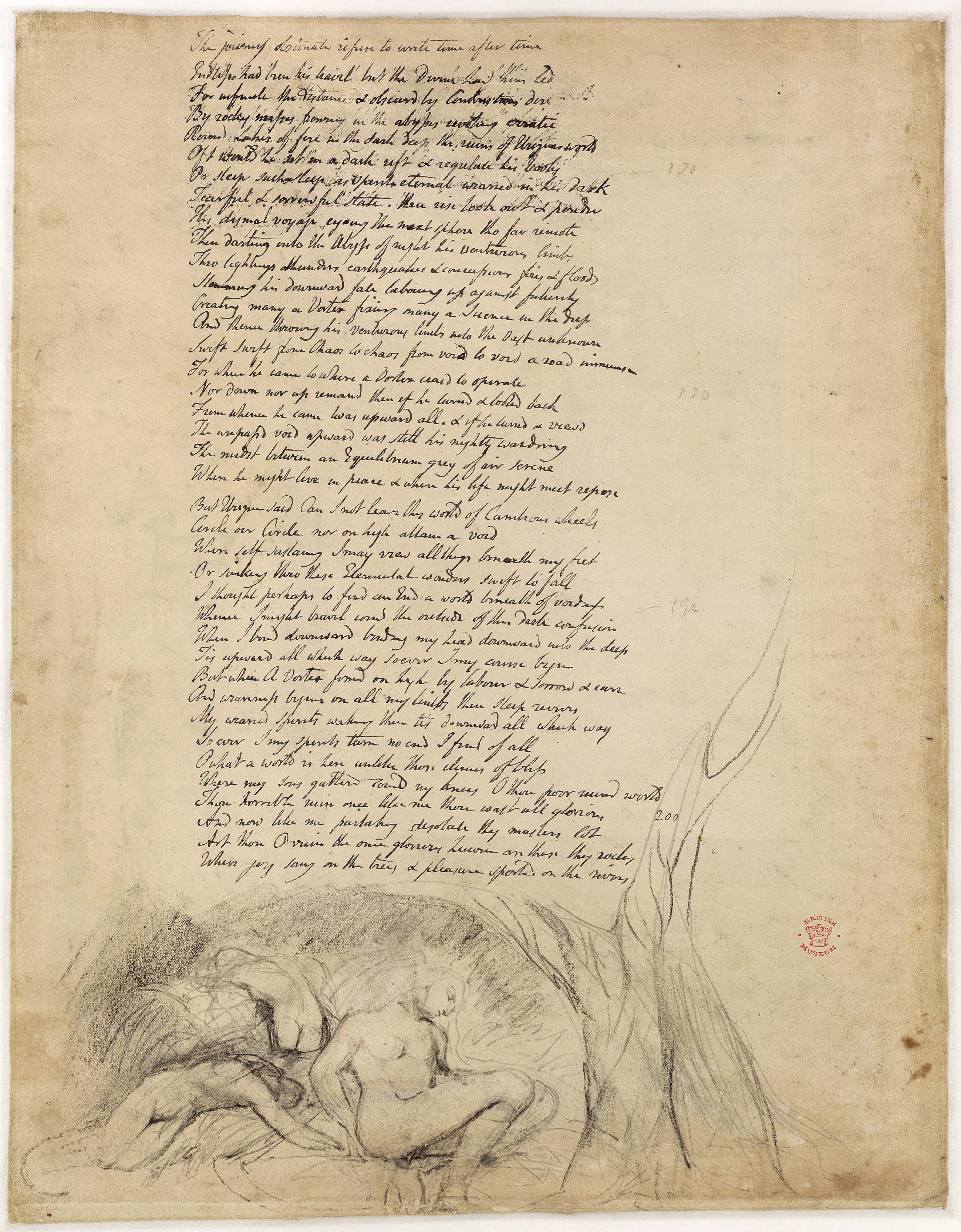

![6th page

Vala incircle round the furnaces where Luvah was clos’d

In joy she heard his howlings, & forgot he was her Luvah

With whom she walkd in bliss, in times of innocence & youth

Hear ye the voice of Luvah from the furnaces of Urizen

20

Ellis

If I indeed am {Luvahs Lord} Valas King & ye O sons of Men

The workmanship of Luvahs hands; in times of Everlasting

When I calld forth the Earth-worm from the cold & dark obscure

I nurturd her I fed her with my rains & dews, she grew

A scaled Serpent, yet I fed her tho’ she hated me

Day after day she fed upon the mountains in Luvahs sight 50

I brought her thro’ the Wilderness, a dry & thirsty land

And I commanded springs to rise for her in the black desart

{But} Till she became a {de[mon]} Dragon winged bright & poisonous

I opend all the floodgates of the heavens to quench her thirst

And

BRITISH

MUSEUM](img/illustrations/BB209.1.26.MS.300.jpg)