article

begin page 148 | ↑ back to topBlake’s Portrayal of Women

In Eden or Eternity, as Los says in Jerusalem, the human form divine is both male and female:

When in Eternity Man converses with Man they enterFocusing on such lines as these, critics have hailed Blake as an advocate of androgyny, of a society in which there is total sexual equality. Irene Tayler has acclaimed Blake’s revolutionary attack on the limited sex-roles of a patriarchal culture and emphasized that in Blake’s liberated Eternity, “there are no sexes, only Human Forms,”1↤ 1 Irene Tayler, “The Woman Scaly,” Midwestern Modern Language Association Bulletin 6 (Spring 1973), 84. forms that experience no divisions between male and female but exist as “one will.”2↤ 2 p. 86. And Michael Ferber, after discussing Blake’s idea of brotherhood as a viable political utopia, insists that “Blake’s fraternity seems not to exclude women” and that “most of Blake’s female figures are symbols of mental states or their projections that can be found in any mind, male or female.”3↤ 3 Michael Ferber, “Blake’s Idea of Brotherhood,” PMLA 93 (May 1978), 446.

Into each others Bosom (which are Universes of delight) In mutual interchange, . . .

For Man cannot unite with Man but by their Emanations

Which stand both Male & Female at the Gates of each Humanity

(J 88:3-5, 9-10; E 244)

But such attempts to read Blake’s Eden and the fourfold Man as genuinely androgynous are belied by Blake’s consistently sexist portrayal of women. The poetic and visual metaphors that Blake develops and uses throughout the corpus of his work typically depict women as either passively dependent on men, or as aggressive and evil. As Susan Fox has persuasively shown in her fine essay on “The Female as Metaphor in William Blake’s Poetry,” Blake portrays the female gender “as inferior and dependent (or, in the case of Jerusalem, superior and dependent), or as unnaturally and disastrously dominant. Indeed, females are not only represented as weak or power-hungry, they come to represent weakness (that frailty best seen in the precariously limited “emanative” state Beulah) and power-hunger (“Female Will,” the corrupting lust for dominance identified with women).”4↤ 4 Susan Fox, “The Female as Metaphor in William Blake’s Poetry,” Critical Inquiry 3 (Spring 1977), 507. Blake’s theoretical commitment to androgyny in his prophetic books is thus undermined by his habitual equation of the female with the subordinate or the perversely dominant. As I shall try to show, in Blake’s apocalyptic human form divine, the female elements continue to function in subordination to the male elements.

Susan Fox has already pointed out that Blake’s heroines are consistently passive. Thel lacks the will to confront the fallen world of Experience and try to redeem it. The more courageous Oothoon lacks the power to break her lover’s or her society’s mind-forged manacles; thus she is, despite her liberated vision, an impotent revolutionary. Ololon, however eager she is to give up her virginity and to unite with Milton, remains a submissive Eve. And Jerusalem can only wait patiently for Albion to acknowledge her love and embrace her; her redemptive role in the poem is circumscribed by male choices and responses. Blake’s attack on domineering women—on Rahab, Tirzah, Vala, Leutha, the Enitharmon of Europe, and all those women whom he denounces as embodiments of the “Female Will”—is overt and repetitive. In a typical passage, Los urges Albion to rebel against the power of the female:

. . . what may Woman be?Blake identifies the Female Will with the vision of the materialistic world as all-sufficient, and thereby re-energizes the patriarchal association of woman with nature. Woman has traditionally been seen as the mother, the womb, the land, earth: she is always fertile, passively waiting to be “plowed and to crop.” Blake implicitly affirms this image of the woman as passive earth-mother by presenting its alternative, the aggressive, independent woman, as someone who thwarts imaginative vision (by insisting on the primacy of the five senses) and at the same time frustrates sensual pleasure (by chastely denying man sexual satisfaction in order to gain power over him). Moreover, Blake’s depiction of the Female Will as a division from the harmoniously unified individual further reinforces the Biblical and Miltonic image of the woman as created from the ribs of the man. Since Blake identifies the Female Will with egoistic selfhood, he implies that women should have no existence independent of men. “He for God, she for God in him,” proclaimed Milton in Paradise Lost, and Blake says much the same thing in A Vision of the Last Judgment: “In Eternity Woman is the Emanation of Man; she has No Will of her own. There is no such thing in Eternity as a Female Will” (VLJ 85; E 552) begin page 149 | ↑ back to top

To have power over Man from Cradle to corruptible Grave.

There is a Throne in every Man, it is the Throne of God

This Woman has claimd as her own & Man is no more!

Albion is the Tabernacle of Vala & her Temple

And not the Tabernacle & Temple of the Most High

O Albion why wilt thou Create a Female Will?

(J 30[34]:25-31; E 175)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Now I wish to suggest some of the specific ways in which the female—as metaphor, as a set of human activities, and as an artistic image—is portrayed in Blake’s work as secondary to the male. In Blake’s metaphoric system, labor is strictly divided on the basis of sex-gender. Males—or the masculine dimension of the psyche—create ideas, forms, designs; females—or the feminine states of mind—can desire (and thus inspire) these forms but not create them. Instead, the female obediently embodies those ideas or designs in physical shapes and perceptible colors. Here, for instance, is the way that Los and Enitharmon build Golgonooza. Enitharmon first calls out to Los,

. . . O Los my defence & guideLos then responds:

Thy works are all my joy. & in thy fires my soul delights . . .

. . . I can sigh forth on the winds of Golgonooza piteous forms

That vanish again into my bosom but if thou my Los

Wilt in sweet moderated fury. fabricate forms sublime

Such as the piteous spectres may assimilate themselves into

They shall be ransoms for our Souls that we may live

. . . his hands divine inspired beganIn this gender-determined division of labor, Los employs the sons “In Golgonooza’s Furnaces among the Anvils of time & space” while Enitharmon employs the daughters in the Looms of Cathedron (FZ VIII, 103:35-36; E 361). Men forge, engrave, draw, construct plans; women then add watercolors, weave coverings (“for every Female is a Golden Loom” [J 67:4; E 217]), and actually build the city, the city begin page 150 | ↑ back to top

To modulate his fires studious the loud roaring flames

He vanquishd with the strength of Art . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

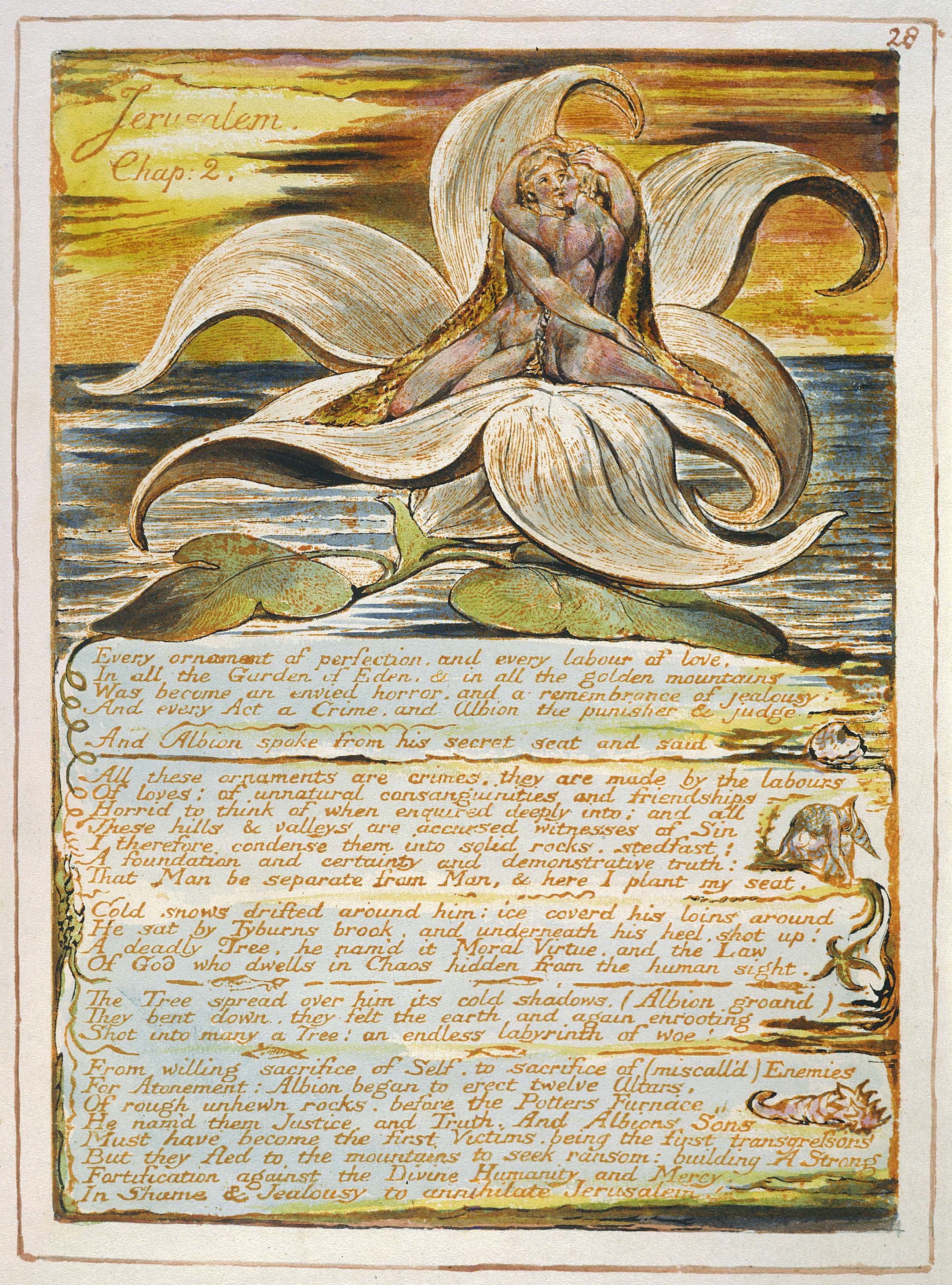

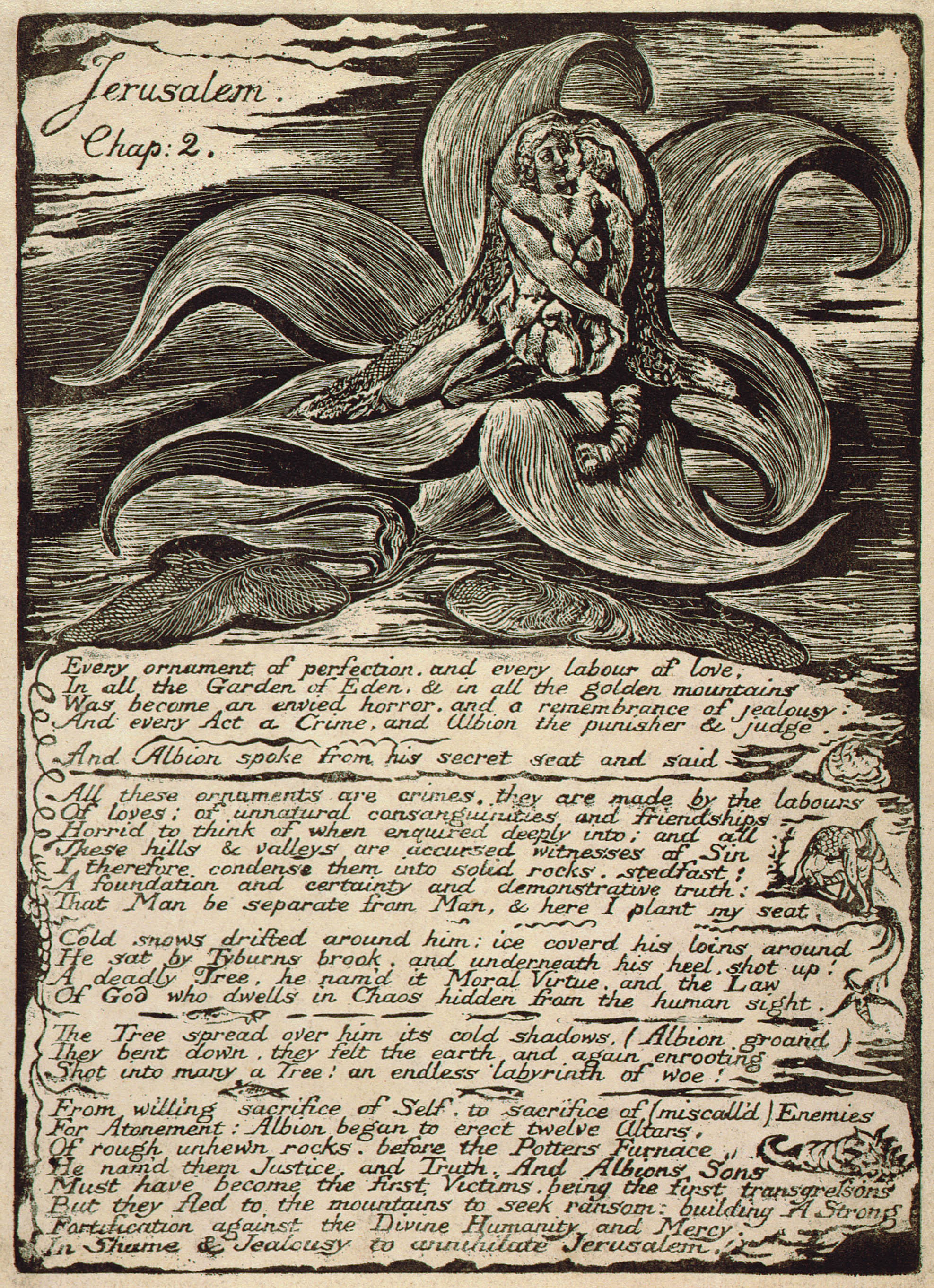

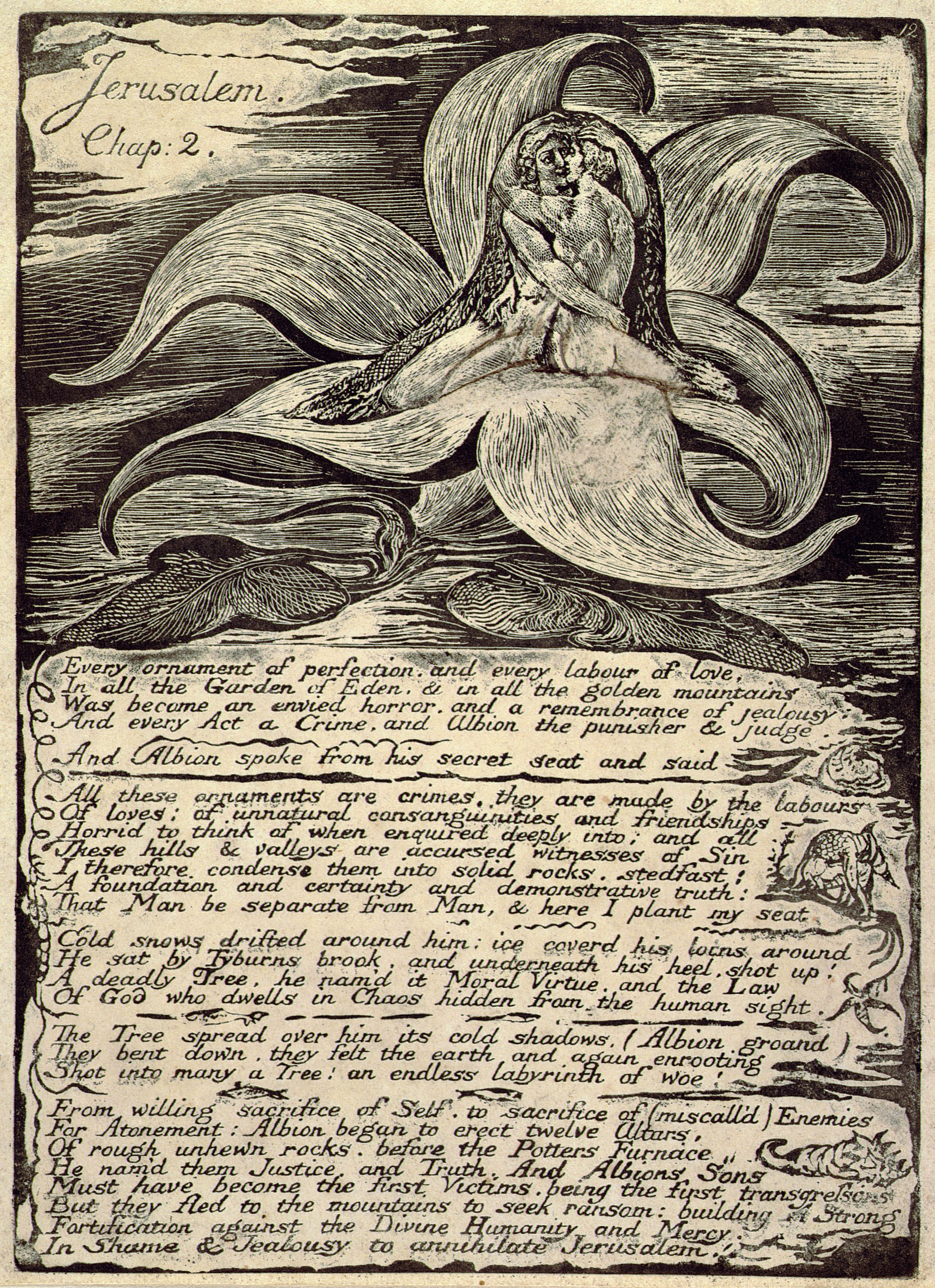

And first he drew a line upon the walls of shining heaven2. Jerusalem, plate 28, copy E, from the collection of Paul Mellon.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

And Enitharmon tincturd it with beams of blushing love

It remaind permanent a lovely form inspird divinely human

Dividing into just proportions Los unwearied labourd

The immortal lines upon the heavens till with sighs of love

Sweet Enitharmon mild Entrancd breathd forth upon the wind

The spectrous dead Weeping the Spectres viewd the immortal works

Of Los Assimilating to those forms Embodied & Lovely

In youth & beauty in the arms of Enitharmon mild reposing

(FZ VII, 90:16-17, 20-27, 35-43; E 356)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

. . . Creating ContinuallyAnd in Milton, Orc says that Jerusalem is the Garment of God, a “Garment of Pity & Compassion” (M 18:35; E 111).

The times & spaces of Mortal Life the Sun the Moon the Stars

In periods of Pulsative furor beating into wedges & bars

Then drawing into wires the terrific Passions & Affections

Of Spectrous dead. Thence to the Looms of Cathedron conveyd

The Daughters of Enitharmon weave the ovarium & the integument

begin page 151 | ↑ back to top In soft silk drawn from their own bowels in lascivious delight

(FZ VIII, 104: 4-10; E 362)

Further, in Blake’s metaphoric system, men prophesy; women then realize that prophecy in historical time and space. Los or Urthona foretells the advent and true nature of Eden, while Cambel and her sisters

. . . sit within the Mundane Shell:

Forming the fluctuating Globe according to their will . . . .

Sometimes it shall assimilate with mighty Golgonooza;

Touching its summits: & sometimes divided roll apart.

As a beautiful Veil so these Females shall fold & unfold

According to their will the outside surface of the Earth

An outside shadowy Surface superadded to the real Surface;

Which is unchangeable for ever & ever Amen.

(J 83:33-34, 43-48; E 239)

Men are intellect (at its most abstract and logical, they are intellect as rationalistic “spectres”); women are “emanations,” divided from and intended to be finally reabsorbed into the male. And in the rare cases where Blake insists that emanations can be male, he specifically defines the function of such male emanations as subordinate. They play the role of mediator or reconciler between conflicting ideas or desires. “For Man cannot unite with Man but by their Emanations / Which stand both Male & Female at the Gates of each Humanity” (J 88:10-11; E 244). Thus both male and female emanations function primarily to facilitate the greater identity of the male human form divine. Blake’s imagery, in all the passages I have been quoting, insists that the masculine principle is prior to the feminine principle and that the female depends upon, serves and reflects the male. As Blake wrote in an early annotation to Lavater’s Aphorisms on Man, “the female life lives from the light of the male; see a man’s female dependents, you know the man” (E 585). Blake’s divine fraternity walk to and fro in Eternity as One Man, conversing in visionary forms dramatic; Blake’s females, waiting at home with the children in Beulah, do not.

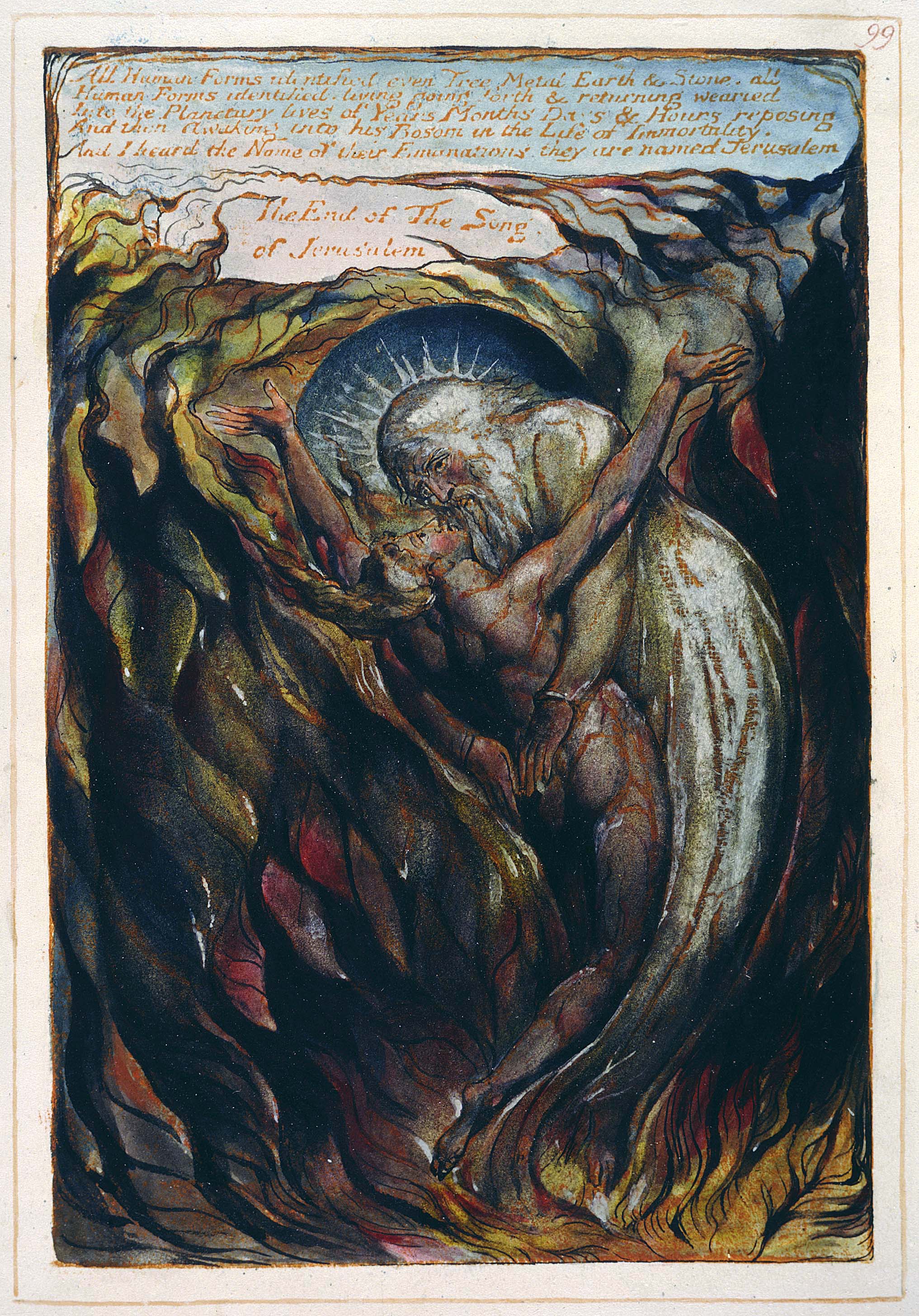

In Blake’s art as well as his poetry, the ideal female is subsumed under the male. In what is perhaps the most striking visual example of this, the liberated Jerusalem on plate 99 (illus. 1) is portrayed so ambiguously that critics have seen this figure both as female and as male. David Erdman endorses the traditional identification of the naked figure as female, as Jerusalem-Britannia, although he also suggests that this figure represents “all youth,” both male and female.6↤ 6 David V. Erdman, The Illuminated Blake (Garden City: Doubleday Anchor, 1974), pp. 378, 375. begin page 152 | ↑ back to top

Such a visual glorification of the masculine human body is of course intrinsic to the Michelangelesque style which

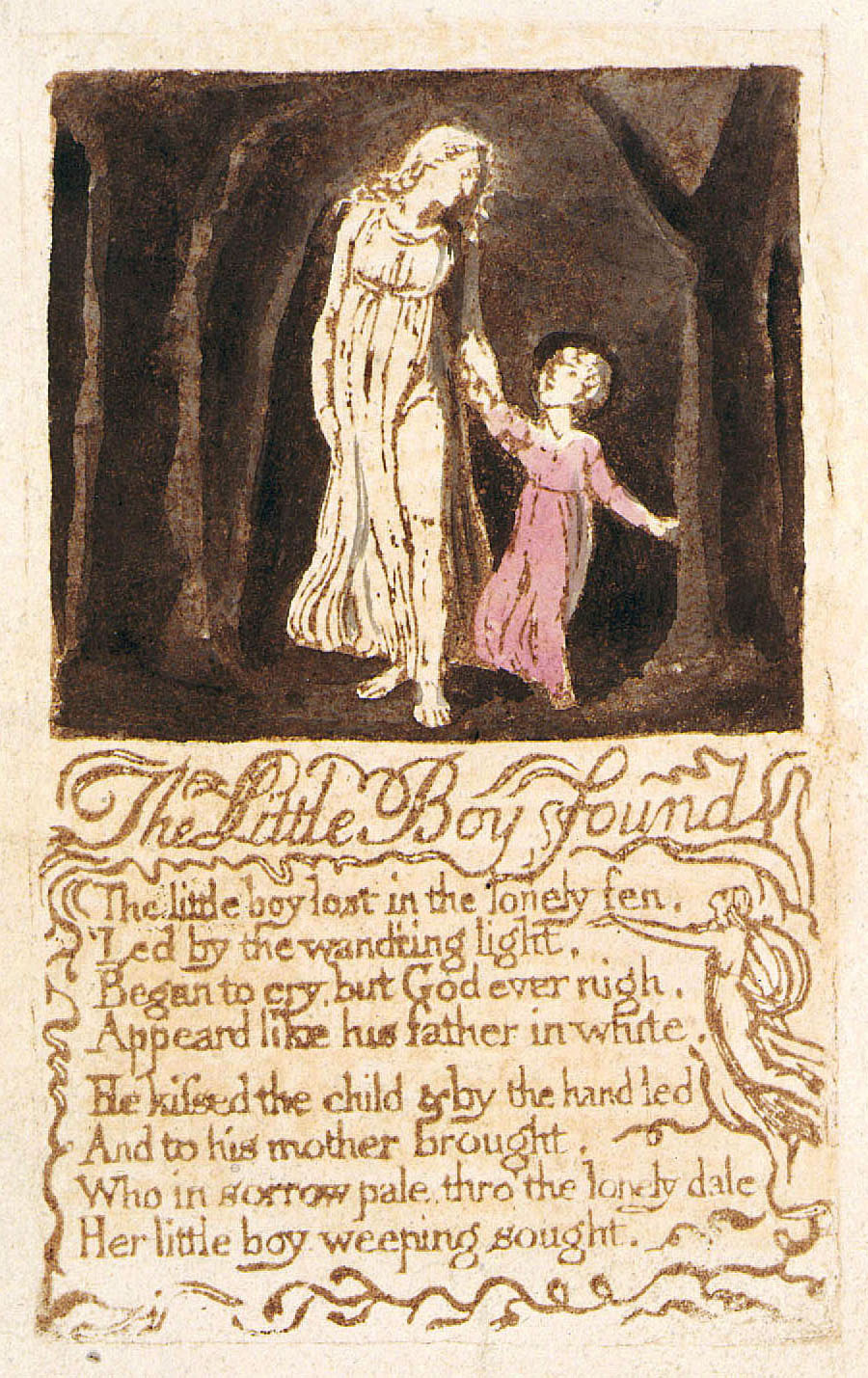

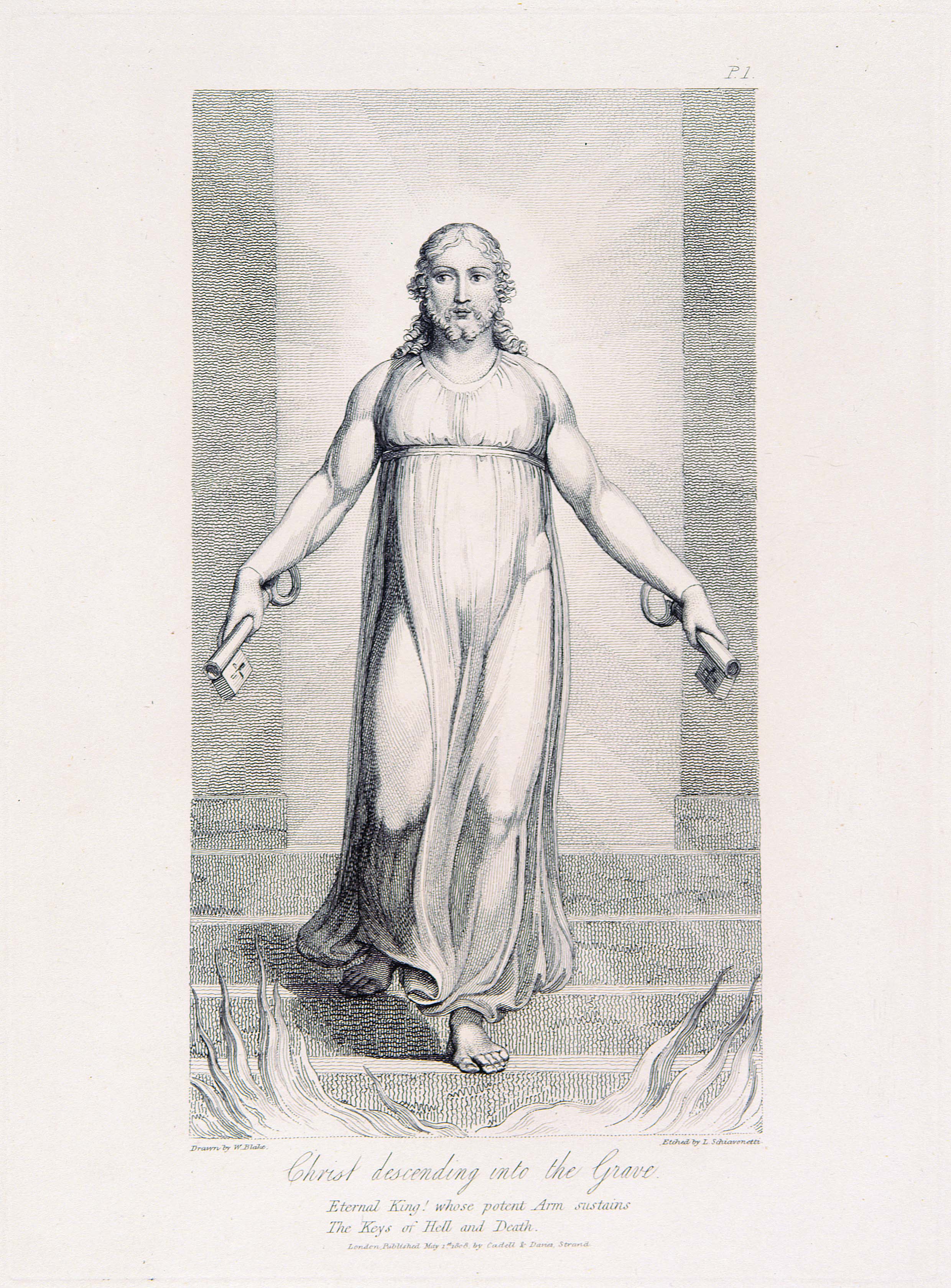

To the suggestion that Blake did feminize the male figure of Jesus as an alternative image of androgyny, as in the illustration for “A Little Boy Lost” (illus. 5) where the rescuer has been identified both as Christ and as the boy’s mother, two counter arguments must be considered. First, in presenting a beardless Christ with long hair and a high-waisted robe, Blake was following an established iconographical tradition, begin page 153 | ↑ back to top

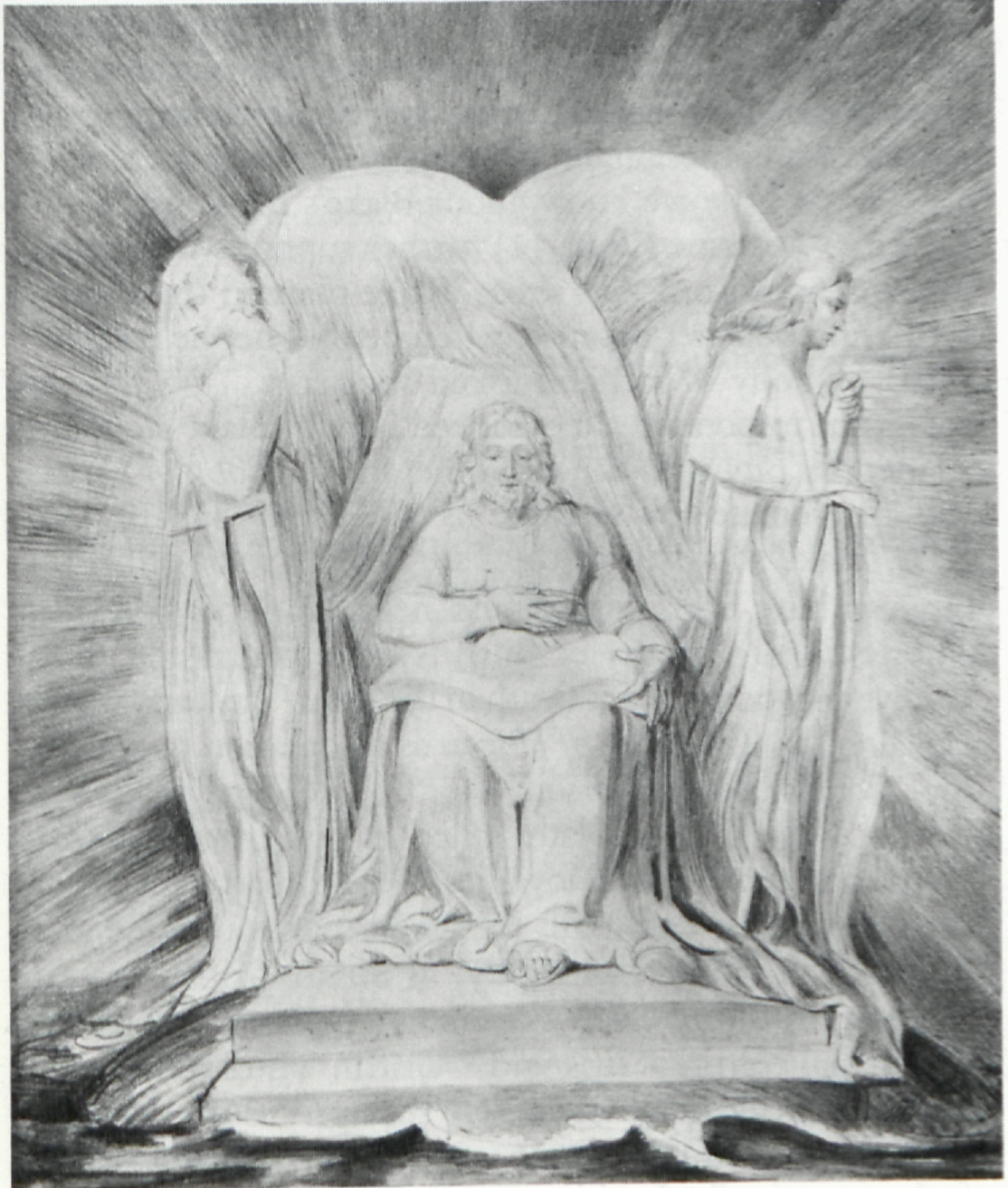

as seen in these three examples. First (illus. 6) is a fourth century mosaic from the Mausoleum of Constantina at Rome, showing Christ giving the Law to Saint Peter and Saint Paul; the second (illus. 7) is a twelfth century stone-relief of the throned Christ from the Benedictine Monastery in Petersburg-bei-Fulda in Germany; and, from the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the third (illus. 8) is a ninth-century Carolingian ivory book-cover, showing Christ the Redeemer trampling the lion, dragon, asp and basilisk.9↤ 9 These images are reproduced in, respectively, Pierre Du Bourguet, Early Christian Art, trans. Thomas Burton (New York: Reynal and Co., 1971), p. 129; Robert Berger, Die Darstellung des thronenden Christus in der romanischen Kunst (Reutlingen: Gryphius, 1926), fig. 66, p. 111; and E. Baldwin Smith, Early Christian Iconography (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1918), fig. 169, p. 250. In all these examples, Christ appears without a beard and wears a robe with a sash beneath his breast.Secondly, Blake on several occasions took pains to emphasize the masculinity of this image of Jesus, as in Christ Girding Himself with Strength (illus. 9) and in his illustration to Blair’s Grave (illus. 10). Blake apparently valued the male human form as a more powerful image of physical beauty and grandeur than the female form; as he wrote in Jerusalem, the masculine is sublime, the feminine is pathos (J 90: 10-11; E 247).

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

I grant that in Blake’s New Jerusalem, male and female functions converge harmoniously in total mutual fulfillment, for in Eden “Embraces are Cominglings: from the Head even to the Feet” (J 69:43; E 221). After all, the masculine artistic imagination needs the feminine manifested art-product to complete the artistic process; the prophet needs historical time and space to vindicate his claim to true vision. But such mutual interdependence should not obscure the fact that, in Blake’s metaphoric system, the masculine is both logically and physically prior to the feminine. The artist can have ideas to which he does not give manifest artistic form; but no art form can exist without a prior creative idea or impulse. Similarly, one can prophesy without history, but history cannot be understood (or some modern historians would say, even exist) without an interpretative idea, structure or “explanation.”

Moreover, Blake consistently refers to his perfected human being as a Man. And while we might agree that Blake is here using Man in the generic sense, to refer to the species begin page 154 | ↑ back to top

mankind and not exclusively to males, nonetheless he is subtly supporting a patriarchal attitude. Since linguistic usage in many ways shapes our conscious experience, to refer to all human beings as Man or mankind devalues woman.10↤ 10 This point has been documented by Wendy Martyna in “What Does ‘He’ Mean? Use of the Generic Masculine,” Journal of Communication 28 (Winter 1978) and in “Beyond the ‘He/Man’ Approach: The Case for Nonsexist Language,” Signs 5 (Spring 1980), 482-93. By continuing to use the sexist language of the patriarchal culture into which he was born, Blake failed to develop an image of human perfection that was completely genderfree. A writer who wished to portray a truly androgynous creature or society would have to transform the language we use. Such radical revisions have occurred in literature: Marge Piercy, in A Woman on the Edge of Time, uses the pronoun “per” to refer to all persons, irrespective of sex-gender. And Ursula Le Guin develops detailed portraits of androgyny in her science-fiction, both of biological androgynes (in The Left Hand of Darkness) and of androgynous societies (on the planet of Anarres in The Dispossessed).We should not condemn Blake for his failure to escape the linguistic prisons of gender-identified metaphors inherent in the literary and religious culture in which he lived. But neither should we hail him as an advocate of androgyny or sexual equality to whom contemporary feminists might look for guidance. Blake certainly recognized the social injustice involved in treating women as property or slaves, as Visions of the Daughters of Albion makes clear. But he did not transcend the prevailing patriarchal assumption of his day concerning the appropriate function of the female. In Blake’s art, women at their best are nurturing mothers. generous sensualists, compassionate lovers, all-welcoming and never-critical emotional supporters.

What little we know about Blake’s relationship with his wife Catherine (illus. 11) further supports this view of Blake as an unconscious sexist. Blake married the illiterate Catherine Boucher because, when he told her he had been jilted by Polly Wood and asked suddenly. “Do you pity me?”, she responded, “Yes indeed I do.”11↤ 11 Frederick Tatham, “Life of Blake” (c. 1832), cited in G.E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 517. Blake later came to identify pity with the feminine: in The Book of Urizen, the “first female now separate” is called “pity” (18:10, 19:1, E77). Blake shows us in the Tate Gallery color-prints that pity can have both positive and negative dimensions. The compassionate loyalty of Ruth is there contrasted to the divisive pity portrayed as death in the print “Pity” and further explained in The Book of Urizen as co-optation by the enemy, “For pity divides the soul” (13:52; E 76). Pity in this sense is what Virginia Woolf later called in The Three Three Guineas a “commitment to unreal loyalties,”12↤ 12 Virginia Woolf, Three Guineas (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1978; Harbinger, 1963), p. 78. a sympathy for the oppressors because “after all, they’re human too.” The identification of women with pity, as Susan Griffin has emphasized in Women and Nature, is a typical metaphor in a patriarchal culture. “It is said,” Griffin writes, referring to Rousseau’s Second Discourse, “that pity is the offspring of weakness and that women and animals, being weaker, feel more pity.”13↤ 13 Susan Griffin, Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her (New York: Harper, 1980), p. 30. In this context, Darwin’s insistence that women are more tender and less selfish than men14↤ 14 See Darwin, Descent, as cited by Eva Figges, Patriarchal Attitudes (New York: Fawcett, 1970), p. 112. becomes a subtle form of male dominance, because it encourages women to heed the needs of others over the needs of their own selves.

As far as I can tell, Catherine Blake played the traditional role of the subservient wife in a patriarchal marriage. She was the student (Blake taught her to read and write and paint); she was Blake’s unpaid domestic servant—as William Hayley reported, “they have no servant:—the good woman not only does the work of the House, but she even makes the greatest part of her husband’s dress & assists him in his art . . . .”15↤ 15 Bentley, Blake Records, p. 106. Above all, she worshipped her husband’s genius. As Crabb Robinson commented, “She was formed on the Miltonic model—And like the first Wife Eve worshipped God in her Husband—he being to Her what God was to him.”16↤ 16 Henry Crabb Robinson, Reminiscences, 1852; reprinted in Bentley, Blake Records, p. 543. However apocryphal, the following anecdote suggests the degree to which Catherine Blake set her husband on a pedestal above ordinary mortals. When the Blakes were living in their small, “squalid and untidy” rooms at Fountain Court, Catherine once excused “the general lack of soap and water” by explaining to George Richmond, “You see, Mr. Blake’s skin don’t dirt.”17↤ 17 Mona Wilson, The Life of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 331n; cf. Bentley, Blake Records, p. 294; “squalid and untidy” is Crabb Robinson’s phrase. A woman who could say that of a man—and a painter!—with whom she had lived for forty years could not have lived in an egalitarian marriage nor experienced psychological androgyny. And if Catherine did not regard herself as Blake’s equal, it is not surprising that in Blake’s Jerusalem women—or the female state of mind—do not receive parity with the male. Having had no emotional begin page 155 | ↑ back to top experience of sexual equality, Blake was not able to portray such a gender-free androgynous ideal in his poetry and art, where male characters and mental functions both outnumber and take precedence over female figures and functions.