REVIEWS

William Blake: His Art and Times, an exhibition organized by David Bindman. Yale Center for British Art, 15 September–14 November 1982. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 3 December 1982–6 February 1983. Catalogue by David Bindman, pp. 192, 200 illustrations, 21 color plates. $15.00, paper.

The exhibition William Blake: His Art and Times was organized by David Bindman and jointly sponsored by the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven (where it was very handsomely installed from 15 September to 14 November 1982—the showing on which this review is based) and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto (3 December 1982 – 6 February 1983). The exhibition was a rather daring undertaking given the enormous amount of attention already paid to Blake in recent years. For example, G.E. Bentley, Jr.’s Blake Books was published in 1977; and since 1978, the year of Martin Butlin’s monumental William Blake exhibition at the Tate Gallery, accompanied by an excellent and informative catalogue, several other important monographs have been published: among them are Butlin’s catalogue raisonné. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, Robert Essick’s William Blake Printmaker, and Bindman’s own The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake together with his Blake as an Artist. Of course there had not been a large scale exhibition of Blake’s art in this country since the one in 1939 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and that show had been selected entirely from collections in the United States. One can understand, therefore, the pressures for a grand display on this side of the Atlantic, all the more so because conservation problems are making Blake collectors wary of lending important objects to the repetitious minor exhibitions that have been organized in great numbers in recent years, and also of showing them at home to anyone other than serious scholars.

The germ of the New Haven/Toronto show came in conversations between Bindman and Katharine A. Lochnan, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Gallery of Ontario, some years ago. The initial intent was similar to that of the 1939 Philadelphia exhibition: to show Blake in North American collections, a much richer body of material than one could find in 1939, thanks principally to the extraordinary acquisitions of Paul Mellon. Thus the Yale Center for British Art, which houses much of the Mellon Collection, was viewed as a most appropriate cosponsor; and, in fact, well over a third of the show was drawn from various Yale institutions (the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Lewis Walpole Library at Farmington, as well as the Paul Mellon and other collections at the Center for British Art). Numerous loans also came from Mr. and Mrs. Mellon’s private collection; the Pierpont Morgan Library; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection; the National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection; and Robert N. Essick. Despite the richness of American collections, however, certain key pieces were necessarily borrowed from abroad—specifically from the Tate Gallery, the British Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Major Blake exhibitions must now be compared to the Tate show of 1978; and in this case, the comparison seems apt in terms of differences in kind. The earlier show was very large, comprising 339 pieces, all of them by or after Blake except for a drawing by his brother Robert that was the source of William’s relief etching, The Approach of Doom. The exhibition emphasized and explored very specifically Blake’s greatest accomplishments as a visual artist, in part by virtually ignoring such aspects of his work as the reproductive engravings that were the artist’s main source of income. In that exhibition, Martin Butlin convincingly demonstrated that Blake “had an intensity of vision, an imaginative scope, and a multiplicity of means of expression . . . beyond most men.”1↤ 1 Martin Butlin, William Blake (ex. cat.), London, 1978, p. 23. In contrast, the New Haven / Toronto show was considerably smaller, comprising some 200 pieces described in 125 catalogue entries (e.g., cat. no. 115 covers sixteen watercolors and engravings for Illustrations to the Book of Job, cat. no. 116 covers thirteen for Illustrations for Dante, and so forth).

Accepting the notion that Blake’s greatness as a visual artist had been demonstrated by the Tate exhibition, begin page 227 | ↑ back to top Bindman set out to explore the intellectual and artistic milieu that helped give this greatness its form. While fewer of the major paintings were here than in the London show, this one was, in fact, more comprehensive, including aspects of Blake’s art not considered in 1978 and showing documentary material as well. In addition, Blake’s own works of art were interspersed with a number of pieces by his contemporaries; and the inclusion of books of historical and philosophical interest to him and others of the period placed his oeuvre in a broad intellectual context.

Bindman carefully balanced and integrated this material so the focus on Blake was in no way diminished. First, the sections devoted to the art of Blake’s time (“The Elevated Style in the 1780s”; “The Revolutionary Background: Blake’s Circles in the 1790s”; “Jerusalem: the Antiquarian Background”; and “The Linnell Circle”) were far fewer than those devoted to Blake’s own art; and the main purpose of them was clearly to provide a background for a better understanding of Blake, although the didactic aspects of the exhibition never overshadowed the aesthetic. Much of the ancillary material was quite small, or in the form of books, and was shown in cases, for the most part leaving the walls to feature Blake. The main exception was the section of drawings and prints representing the scope of narrative subjects (“The Elevated Style”) prevalent in English art of the 1780s, and in which pieces by or after John Flaxman, Richard Cosway, John Mortimer, Benjamin West, George Romney and Henry Fuseli were hung. In them one found allusions to the art of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance of the sort one sees throughout Blake’s own oeuvre.

The basic arrangement of the Blake material was chronological: “The Engraver’s Apprentice, 1772-79”; “Radical History Painter: the 1780s”; “Making a Living: Reproductive Engraving”; “Relief Etching and Experimental Printing, 1788-96”; “Illuminated Books and Prophecies, 1788-95”; “Separate Colour Prints, c. 1794-1805”; “After the Prophecies: Illustrated Books”; “An Understanding Patron: Thomas Butts and Paintings from the Bible, 1799-c. 1809” (a conscious contrast, perhaps, to the section in the Tate show called “The Hazards of Patronage: William Hayley and ‘The Grave,’ c. 1799-1806”); “Blake in Felpham, 1800-1803”; “Milton: Prophecy and Illustrations, 1801-c. 1820”; “Blake’s Exhibition of 1809: The

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

One realized that, given the very large body of work that Blake produced, each piece on display was purposefully selected to function in a number of ways. Some pieces allowed for iconographical comparisons both within Blake’s own oeuvre and in relation to the work of other artists. Some made stylistic and technical points. Some had historical or philosophical import. Various threads were woven throughout the fabric of the exhibition, and the viewer was able to perceive again and again relationships between the sections and to sense the totality in a body of work through selected pieces. To mention only a few instances, The Witch of Endor Raising the Spirit of Samuel is seen in a 1783 version by Blake (cat. 11), in a later version by him, c. 1800-1805 (cat. 77), and in an engraving by William Sharp after Benjamin West (cat. 22, illus. 1), thus allowing Blake’s own evolution to be studied while also comparing his representation of the subject with that of another artist. Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (cat. 16) introduces the theme of fairies which is often picked up in Blake’s later work (e.g., as Bindman points out, in the title page for Jerusalem, cat. 99b). From Blake’s scores of reproductive engravings, Bindman selected works after earlier masters (Watteau, cat. 25), as well as works after Blake’s contemporaries (e.g., Fuseli, cat. 27).

Points about method, too, were well managed. The technical range of Blake’s reproductive prints was evident—from the stipple engraving that the artist presumably despised (e.g., Zephyrus and Flora, after Stothard, cat. 26), through the dot and lozenge engraving technique at its most spectacular in the exceedingly dramatic Head of a Damned Soul after Fuseli (cat. 28). In the “Relief Etching and Experimental Printing” section, the single surviving fragment of an etching plate used by Blake for relief printing (a cancelled plate from America) was shown with a proof impression from it (cat. 34, 35), and other trial proofs of various sorts helped the viewer to see and understand Blake’s processes. Particularly interesting was a proof of the title page of The [First] Book of Urizen with areas of monotype-like color printing, but lacking final watercolor refinements (cat. 37). This section showed initial working phases of Blake’s processes, the final results of which were demonstrated in all of their rich variety later in the exhibition. In contrast, a copy of Joseph Ritson’s Select Collection of English Songs with conventionally engraved illustrations by Blake and others after Stothard (cat. 32) vividly demonstrated the differences between traditional book illustration and Blake’s personal inventions and methods.

Among the most rewarding sections of the show, one which explored the development of Blake’s conceptual (spiritual) and technical sophistication, was “Illuminated Books and Prophecies.” On view were There is no Natural Religion including the unique “Application” plate (cat. 38b) given by Sir Geoffrey Keynes to the Pierpont Morgan Library (important not only because it is unique, but also because it is an early example of the figure which later is seen as Newton, cat. 56); The Book of Thel; The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; Visions of the Daughters of Albion; and several separately mounted pages from the very beautiful colored copy of America a Prophecy in the Mellon private collection, unusual in that it is richly colored, whereas most surviving copies are uncolored. Three copies (F, P, U) of a single page from Songs of Innocence (cat. 39) colored at different periods of Blake’s career showed his evolution in unifying on the page the image and text relationships. In the earliest (copy F, which Bindman cites as a copy of Songs of Innocence to which has been added an incomplete copy of Songs of Experience) the delicate washes tend to heighten only the image, while in the latest (copy U, colored 1815 or later), the color is rich, vibrant, and heightened with gold, fully illuminating both image and text. Quite another matter, and equally marvelous to see, the display of five of the seven known copies of Urizen (cat. 45), including the only one colored in watercolor rather than color printed, showed the great variety in Blake’s handcoloring of one title during a rather concentrated period of time (probably 1795-96 for the color printed versions with the watercolored copy probably dating from the early 1820s).

In the section “Separate Colour Prints, c. 1794-1805,” examples from the Small and Large Book of Designs were represented as well as six images (in seven impressions) of Blake’s series of twelve elaborate monoprints (color printed drawings, as they are more generally known): God Judging Adam, Pity, The Good and Evil Angels Struggling for Possession of a Child (illus. 2); Christ Appearing to the Apostles after the Resurrection, Hecate, and Newton (cat. 51-56). Until recently, all impressions of the twelve subjects, each known in from one to three impressions reworked with paint to a varying extent and every one unique, were thought to date from c. 1795. When the Tate Gallery Newton was removed from its mount in preparation for this exhibition, however, it was found to be on paper with an 1804 watermark. This piece was hung side by side with the one other know version of the subject, a far less familiar one, in the collection of the Lutheran Church in America, Glen Foerd at Torresdale (illus. 3). These two Newton prints present quite a challenge: to the 1804 watermark on the Tate sheet must be added the fact that its surface is exceedingly rich and painterly, making it look quite different from the Lutheran Church version (see David Bindman’s “Afterword” elsewhere in this issue). The painterly surface caused speculation that the Tate version was entirely a painted rather than a reworked color print of the subject. The present writer, like Bindman, is not at all convinced that this is so.

Another discovery as important as the 1804 watermark begin page 229 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Blake’s expressive range in his illustrations for Young’s Night Thoughts, Blair’s Grave, and Gray’s Poems was displayed in the selection of watercolor designs for them. In the section “After the Prophecies: Illustrated Books,” one also found a rejected design and the unique proof of Blake’s own white line etching (printed relief) for the “Death’s Door” plate (cat. 64a,b) in The Grave.

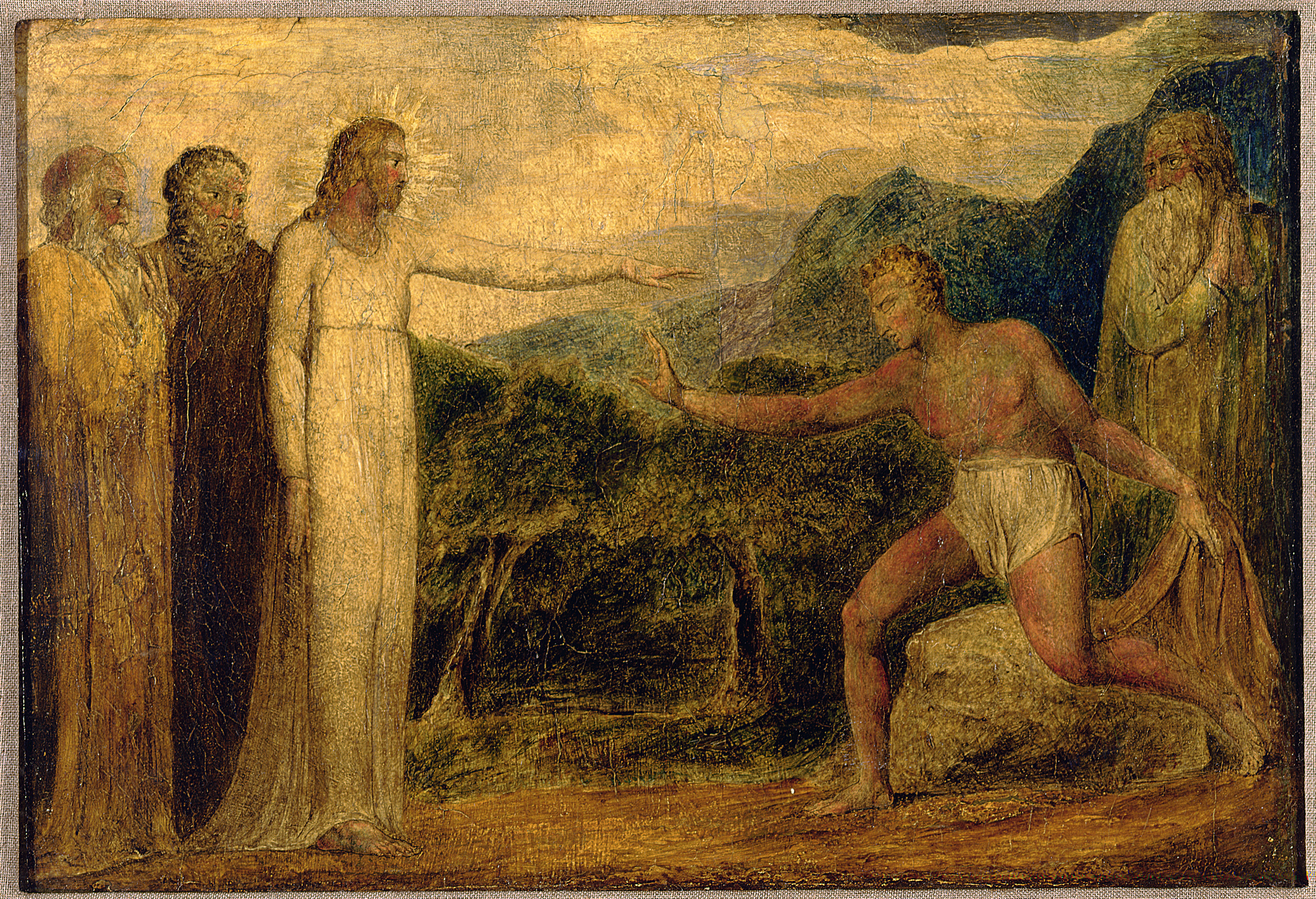

Although conservation considerations prevented the loan of many of the tempera paintings that Blake executed under the patronage of Thomas Butts, there were five to be seen. Among them were Christ Giving Sight to Bartimaeus (cat. 72, illus. 4) and, in a splendid state of preservation, The Virgin Hushing the Young John the Baptist (cat. 70) from a private collection in Chicago; it is always rewarding to see little known works not in the public domain included in exhibitions. In addition to the temperas, the Butts section included a number of watercolors, the most important, perhaps, being those for Revelation, (cat. 80-83) a theme which, as connected with millinarianism, was important to the context that Bindman emphasized in his catalogue (see below).

Hayley’s patronage was less successful than Butts’ and the section of the exhibition devoted to the Felpham period

begin page 230 | ↑ back to top relied heavily on documentary material: a letter of 1800 to John Flaxman beside one of two and a half years later to James Blake showed Blake’s delight at being in the country turn to great dismay. The star of this section of the show, however, was the very tiny (4 3/16 × 2 ½ inch) tempera on copper, The Horse (cat. 89), related to the illustration in Hayley’s Ballads. From Mr. and Mrs. Mellon’s private collection, dating from 1805-06 or possibly from as late as the 1820s, the piece is a jewel.During his Felpham sojourn while Blake was helping Hayley with Cowper’s edition of Milton, he became preoccupied with the great poet, and the results of this preoccupation were seen in the section “Milton: Prophecy and Illustrations, 1805-c.1820.” The earliest Milton illustrations, the 1801 Comus watercolors in the Huntington Library, were not available for loan, the same being true for the first (1807) set of Paradise Lost illustrations. However, selections from the 1808 Paradise Lost were on show (as well as an example of the third [1822] set, seen in the section devoted to Blake’s last decade), as were selections from the 1815-20 Comus illustrations and from those to L’Allegro and Il Penseroso of the same period. The concentrated energy in these small images of the late teens as well as their rich coloration foretell the somewhat larger and equally magnificent Dante series that comes at the end of Blake’s life. Complementing the Milton watercolors, the single complete copy of Milton a Poem (cat. 90), with fifty plates (copy D) was on show. As Bindman pointed out in his catalogue, this most elaborate of the extant copies of Milton handsomely complemented the only known colored copy of Jerusalem, also on view (cat. 99).

The section devoted to Blake’s unsuccessful 1809 exhibition included its catalogue which sets forth the artist’s most distinguished writing on his own art. Here, too, most of the relevant surviving temperas (“frescos”) were too fragile to travel, and were represented by related material: e.g., a pencil study, The Bard (cat. 96) of 1809, The Canterbury Pilgrims engraving, accompanied by the original copper plate from which it was printed and the 1809 prospectus for the piece (cat. 97). The star in this section was the National Gallery’s Last Judgment (cat. 98, illus. 5) drawing. One technical disagreement here: I suspect this sheet probably was not done with pen and ink at all, but, rather, with a very fine brush and watercolor. I suspect this may also be true for many pieces that are recorded in Bindman’s catalogue and elsewhere as having been reworked with pen and ink.

Sixteen plates of the one hundred in the exquisite and only colored copy of Jerusalem in the Mellon Collection were on view, including the title page and all four full-page frontispieces. A Description of Jerusalem by Richard Brothers (cat. no. 101) in the section “Jerusalem: The Antiquarian Background” reinforced the belief that the return to Jerusalem was central to millinarianism (as was the idea of apocalypse noted earlier). Other books dealing with the history (mythological and otherwise) of the British Isles were included here as well.

A diverse group of pieces represented Blake’s last decade, among them, his only wood engravings, the illustrations for Thornton’s Virgil (cat. 106), the Pierpont Morgan Library’s marvelous pencil study for Blake’s enigmatic Arlington Court Picture (cat. 108), one of two known impressions of the Laocoön engraving (cat. 110), the late relief-etched treatises The Ghost of Abel, and On Homer’s Poetry and On Virgil (cat. 111, 112). The major emphasis of this section, however, as would be expected, was on the Job and Dante illustrations. The Job display (cat. 115) included six of the early (1805-10) watercolors done for Thomas Butts, now in the Morgan Library, and ten of the series of twenty-one engravings, including all six derived from the watercolors on show. This allowed for comparison of the early and later versions (in different techniques) as well as offering a broad representation of the images. Blake’s agreement with Linnell, Linnell’s account book of the Job project, and a related receipt were included in the final, “Linnell Circle,” section of the show. In the watercolors for Job one sees how specific Blake could be in working studies that later were transformed into another medium, while, in contrast, the Dante watercolors show how freely-handled ideas might take form.

The Dante series (cat. 116) was represented by five watercolors to the “Inferno” (plus four of the seven engravings, all of them for the “Inferno”), three watercolors to “Purgatorio” and, in a sense ending the exhibition, the “St. Peter, St. James, Dante, and Beatrice with St. John also,” for “Paradisio.” In one instance, “The Pit of Disease: The Falsifiers,” the watercolor (one of the more highly finished ones in the series) was shown with the engraving; and the selection of watercolors generally showed the diversity of finish in the set, from subjects that are very loosely worked (e.g., “The Angel Boat”), to highly finished ones like the “Paradiso” scene noted above. For the record, Blake’s seven copper plates for the Dante series are not now in the Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection, as indicated by Bindman, but in the National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection.

“The Linnell Circle” section included Blake’s 1825 pencil drawing, Portrait of John Linnell (cat. 117, illus. 6), two works by Linnell, and an engraved portrait of the engraver Wilson Lowry, worked jointly by Linnell and Blake (cat. 119). Included, too, were works by George Richmond and Samuel Palmer as well as George Cumberland’s Calling Card (cat. 125), “the last thing Blake attempted to engrave,” according to Bindman, quoting Mrs. Blake.

Exhibitions such as this confirm beyond any doubt the importance of the exhibition form as a carrier of knowledge quite distinct from fully illustrated volumes about the work of an artist. The enormous, if subtle, differences between the two Newtons are observable only begin page 231 | ↑ back to top with the two works physically side by side. Only in this circumstance can one observe similarities, especially in tactile aspects, between the Tate version of Newton and other color printed subjects, similarities that demonstrate (once the question arises) that the Newton does have a printed base—albeit one that probably was made later than previously had been thought (one recalls that similar questions and observations arose from viewing three impressions of The Ancient of Days in the Tate exhibition). Only when seen side by side with the other color prints can the clearly defined greyish outline in God Judging Adam stand out as having been printed in relief from an etched plate. And only in an exhibition of this kind in which Blake is placed next to his contemporaries can one see his extraordinary distinctiveness. For example, Blake’s Job engraving (cat. 15) practically jumps off the wall as it demonstrates the artist’s exquisite understanding of the expressive potential of the burin, all the more so when it is placed just several feet from a piece by one of the most admired craftsmen of the period, William Sharp. Sharp’s Witch of En-dor after Benjamin West, mentioned earlier, is strikingly dull in its repetitious description of form. If one does nothing more than study the edges of the folds of clothing in Blake’s Job in contrast to similar forms in Sharp’s piece, it is possible to glimpse the power of Blake’s imaginatively complex world. Although Blake used precisely the same engraver’s vocabulary in general use at the time, parallel strokes, cross hatching, dot and lozenge, etc., each of his marks is made with a passion that appears to be without bounds.

Throughout his catalogue, Bindman captures the spirit of Blake, summarizing that “Blake . . . intends us always to go further and find that our certainties have evaporated.”2↤ 2 David Bindman, William Blake: His Art and Times (ex. cat.), (New Haven and Toronto, 1982), p. 44. He points out how Blake made use of many of the artistic conventions of his time while rejecting others. Touching upon the ideas that were in the air, so to speak, in Blake’s London, Bindman doesn’t try to project a cause and effect relationship. The same is so when he mentions possible influences on Blake, of, for example, children’s books and satirical political cartoons. He discusses Blake’s relationships with and differences from his artist colleagues while touching as well upon aesthetic affinities that are less clearly pinned down (e.g., Bindman makes cogent comparisons of Blake with Goya while pointing out that it is unlikely that the two artists actually knew each other’s work). Blake’s ambivalence toward confining systems is observable throughout his career. For example, while his relief-etching inventions allowed him to bypass commercial publishers, he continued to try to find both publishers and patrons. As Bindman points out, given Blake’s revolutionary stance his obscurity was undoubtedly his protection. Despite this obscurity Bindman offers us remarkably succinct summary accounts of Blake’s themes, always maintaining a sense of the complexity that is essential to a true study of Blake in depth, but allowing the reader to move intelligently through the exhibition knowing the abbreviated catalogue information alone.

One of Bindman’s major theses is that Blake’s visionary stance had many parallels with the prevailing dissenting philosophical thought of his time, specifically the millenarianism of Richard Brothers and Joanna Southcott. A central unifying issue was the prophecy of an apocalyptic, revolutionary, and vengeful destruction of the fallen, corrupt, materialistic world, and the beliefs that true redemption was to be found through Christ and that the meaning of the Bible was available in every age, but only to a few privileged individuals who were guided by an inner light. For Blake, this inner light obviously was the force behind his art which he valued as a form of prayer.

Blake is a difficult artist. This exhibition places him in context; yet, in context, he remains apart. The exhibition rather reinforces one’s awareness of Blake’s own peculiar grasp of the neoclassical and the horrific (the serene juxtaposed with the bizarre), his placement of almost naive formal generalization next to imaginative particularization. One sees obviously exquisite skill displayed next to offhanded clumsiness; one sees extraordinarily subtle color relationships in contrast to rather obvious use of the primaries. One feels delight and pride and sadness and shame at being part of the human experience.

At home, later, one can review the catalogue, rethink Bindman’s ideas on Blake’s influences and relationships, can further ponder the narrative aspects of the meaning of images that are graspable from catalogue reproductions, essentially in black and white (although this catalogue does include twenty-one color plates), in which objects of various sizes fit into the scale of a page or a column. One can only try to recall what was understood about the world in a new way having had the privilege of peering from the distance of a few inches at the tiny forms in the Morgan Library watercolors for L’Allegro and Il Penseroso (delicate, brightly colored, and sprightly drawn) having just been knocked-out from across the room by the powerful, somber, dense, dark, watercolor illustrations to the Book of Revelation which were brought together from Brooklyn, New York City, Washington, and Philadelphia for a rare comparative viewing in New Haven and then Toronto.

Such experiences give one a feeling of elation, and this elation is heightened by awe at the range of this particular human mind. In discussing another intelligence, that of Frederich Hölderlin, Richard Unger made some observations about Blake in a literary context, but they seem equally apt here: “Like Blake, Hölderlin was not adequately valued or even partially understood until the twentieth century. And he has likewise remained permanently esoteric and ‘difficult’ for us; critics are still grappling with the literal meaning of his major poems. But, also, as in the case of Blake, it is perhaps the very quality of this difficulty which often intrigues us. For these begin page 232 | ↑ back to top poets sometimes appear to understand more than we do; they admittedly share our problems but we suspect they have seen these problems more clearly and in greater depth. And in our interpretations it may seem that (rather than explaining their ‘relevance’) we are attempting to discover something which, in the silence of their texts, they already know”3↤ 3 Hölderlin’s Major Poetry: The Dialectics of Unity (Bloomington and London: Indiana Univ. Press, 1975), p. 7. My thanks to Larry Day for bringing the Unger paragraph to my attention.