article

begin page 94 | ↑ back to topTHE FELPHAM RUMMER: A New Angel and “Immoral Drink” Attributed to William Blake

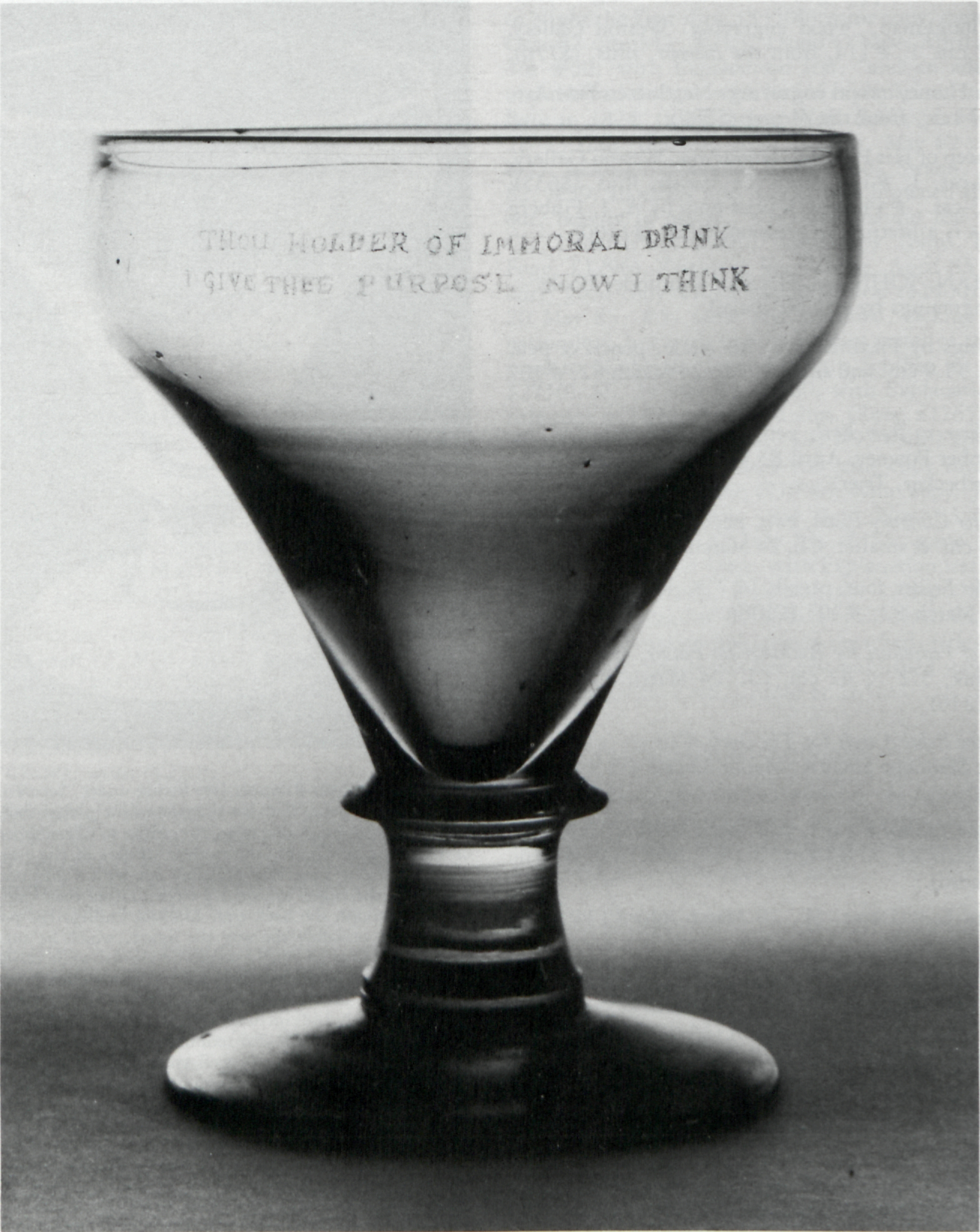

A new document attributed to William Blake has recently appeared in a surprising form. It is a drinking goblet of the type called a rummer, with a very faint etching of an angel on one side of the bowl (illus. 12 in Essick, above), a curious couplet of indifferent quality on the other side (illus. 1), and on the stem Blake’s name (illus. 10 in Essick, above) and the date August 1803 (illus. 11 in Essick, above). As art and as literature, the achievement is certainly indifferent by Blake’s standards, but, if the work really is by him, it is fascinating because of the medium—Blake was not previously known to have made designs on any other solid surface than metal or wood—and because of the biographical context, for it was in August 1803 that Blake was charged with sedition. The purpose of the present note is to describe the object and how it was made, to record its history, to test its authenticity, and to suggest its significance.

A “rummer” is a goblet made usually of thick glass with a comparatively large bowl and a short stem; an ordinary rummer holds four ounces or more of fluid and is up to 24 cm. high.1↤ 1 E. Barrington Hayes, Glass through the Ages (1970), p. 200; there are also Giant Rummers over 24 cm. high and Mammoth Rummers over 28.8 cm. high. For reproductions of rummers made about 1800, see L. M. Bickerton, An Illustrated Guide to Eighteenth-Century Drinking Glasses (1921), pl. 685-86 (c. 1805), pl. 687 (c. 1805), pl. 688 (c. 1805), pl. 689 (early nineteenth century), pl. 691 (c. 1800); Derek C. Davis, English and Irish Antique Glass (1964), pl. 69 (1800-25), pl. 70 (c. 1800, “finely wheel engraved”), pl. 71 (dated 1746, the design in “Diamond point”); English Glass, ed. Sidney Crompton (1967), pl. 168 (c. 1810, rather like the Felpham Rummer, “with ovoid~ogee bowls collared at base on short plain stem”), pl. 169 (early nineteenth century), pl. 170 (early nineteenth century); Hayes, pl. 35d (c. 1805), pl. 42d (c. 1800), pl. 95h (no date suggested, very like the Felpham Rummer, with the same foot but of course made of glass); Hugh Wakefield, Nineteenth Century British Glass (1961), pl. 45A-B (c. 1805). The somewhat stubby rummer flourished as a type from the late eighteenth century, partly because the Glass Excise Acts of 1777-1787 “in effect abolished tall, long-stemmed drinking glass,”2↤ 2 Francis Buckley, A History of Old English Glass (1925), p. 37. which had previously been popular.

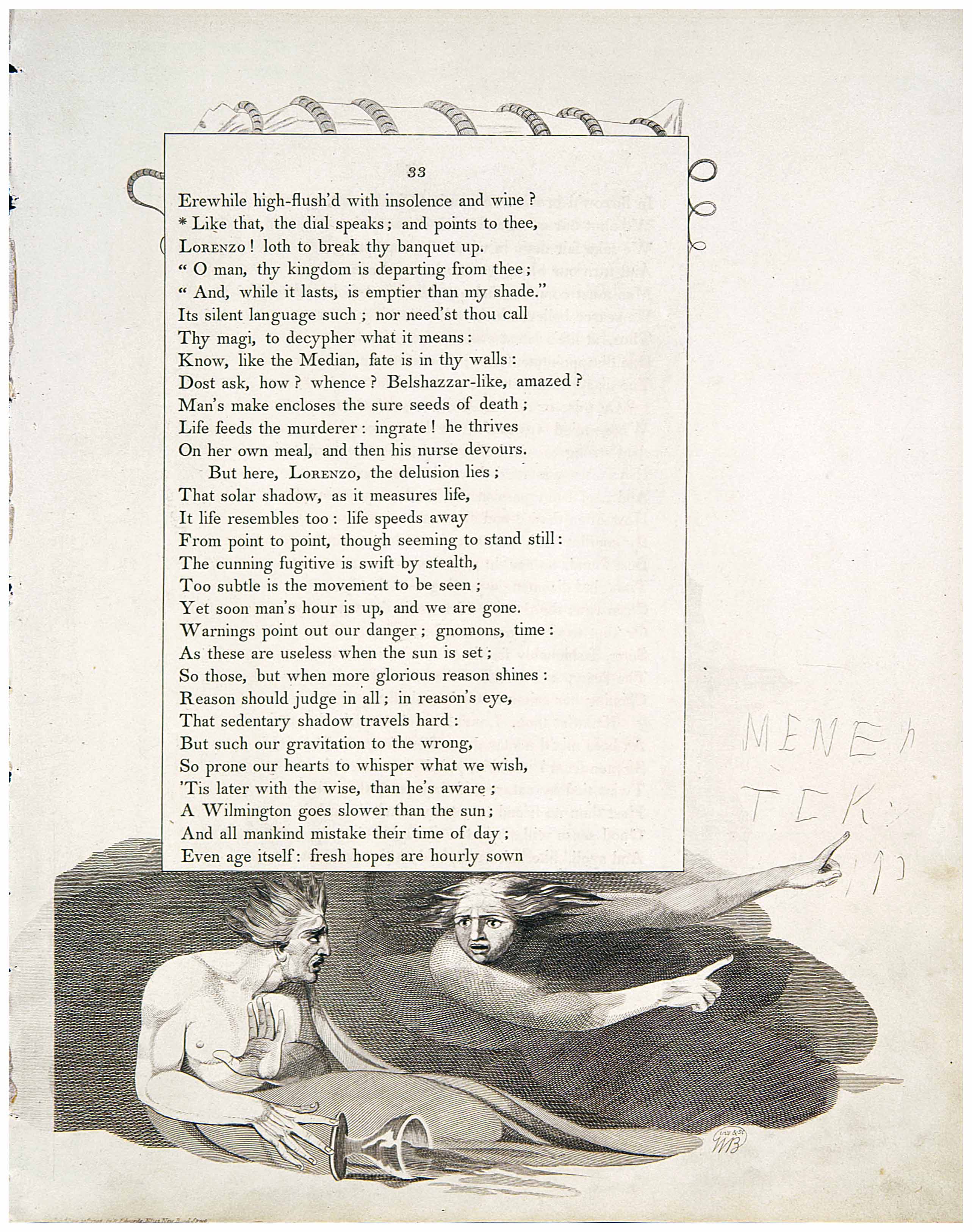

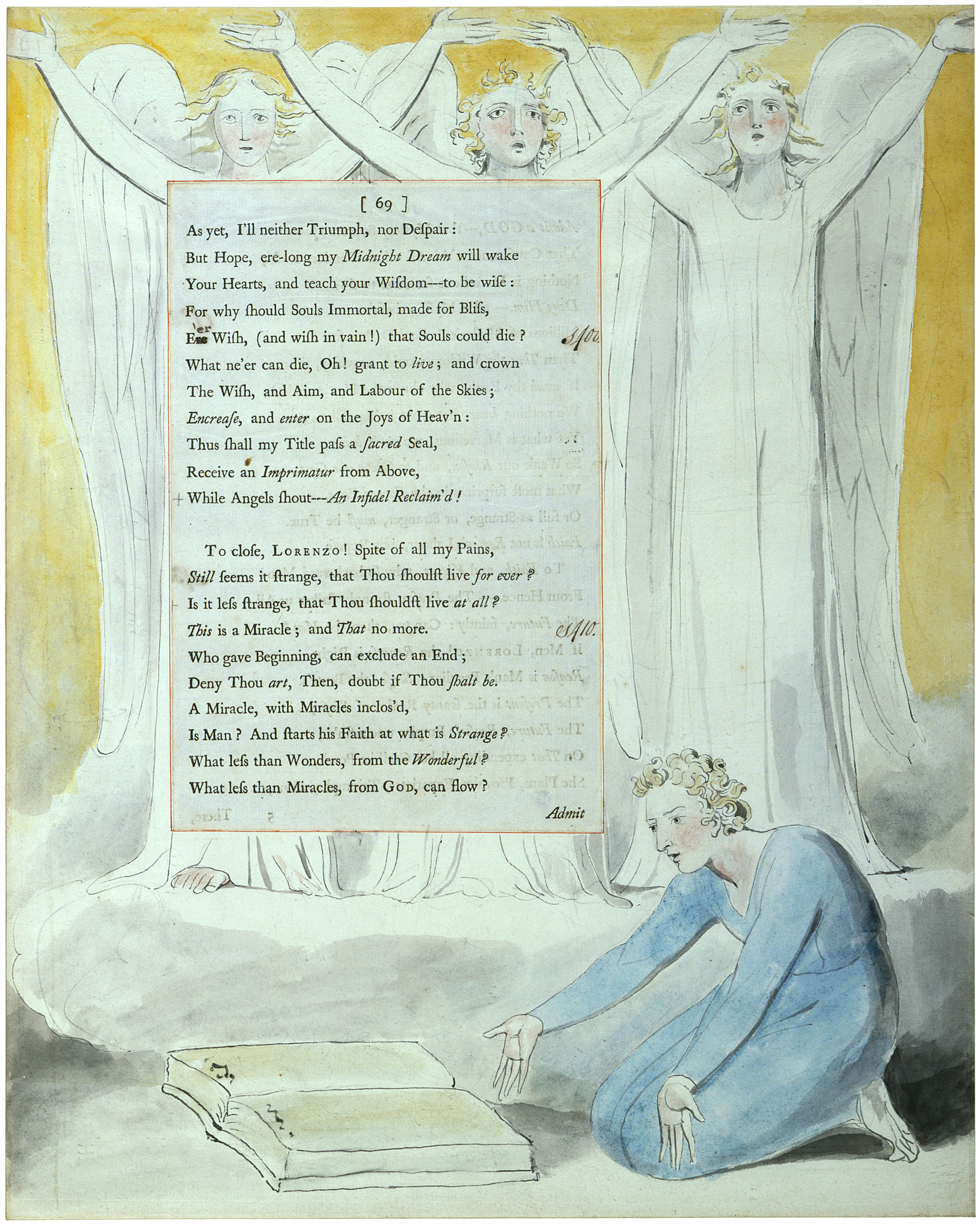

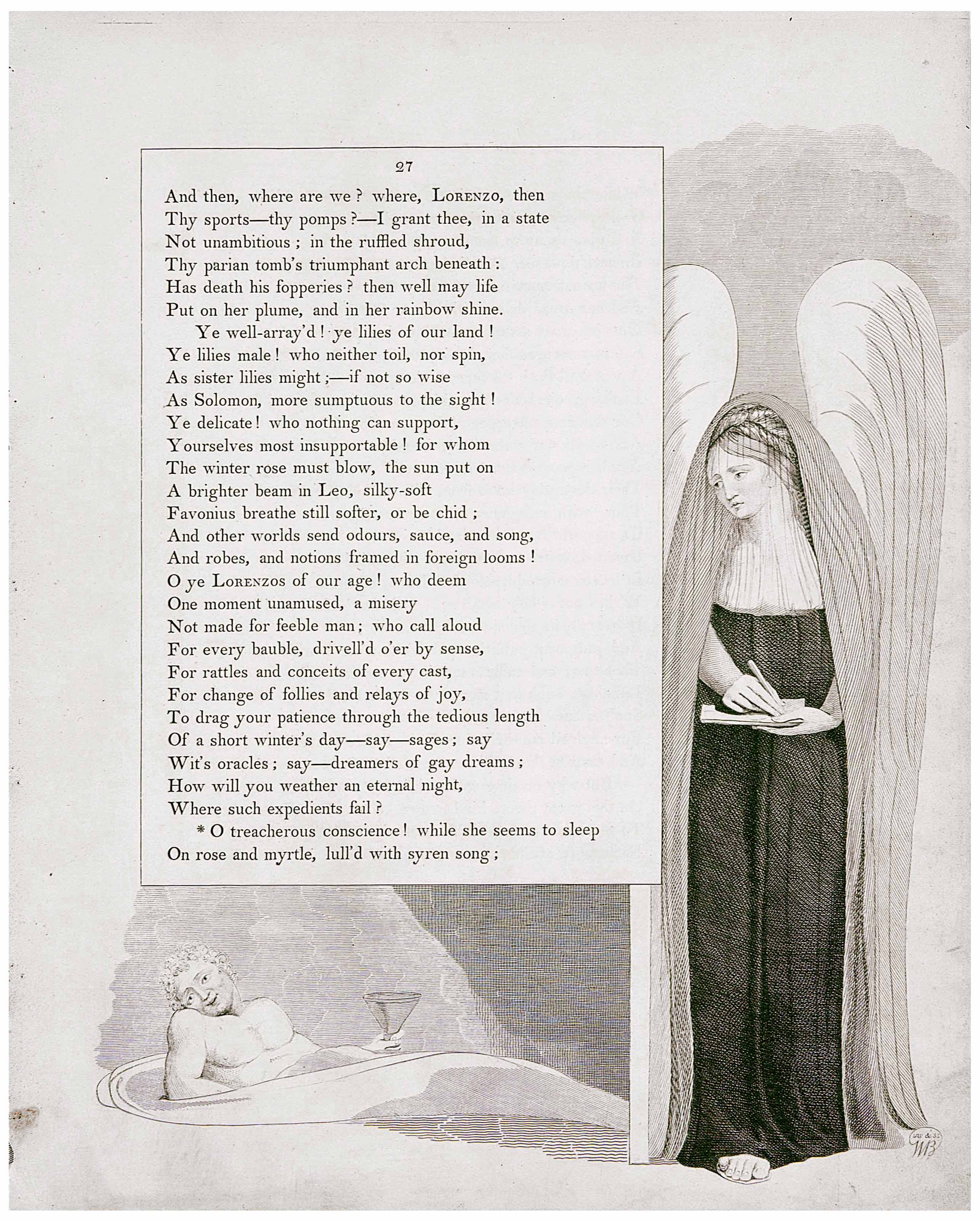

Blake was clearly familiar with rummers, for he often represented them in his designs of about 18003↤ 3 For example, “Lot and His Daughters” (1799-1800), “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary” (1803-05), “The Magic Banquet,” for Comus (c. 1801, c. 1815), “Comus with his Revellers” (c. 1815), “The Brothers Driving Forth Comus” (c. 1801, c. 1815), “Christ Ministered to by Angels,” for Paradise Regained (c. 1816-20), “The Whore of Babylon” (1809)—see Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (1981), catalogue nos. 381 (pl. 485), 489 (pl. 563), 527.5 and 528.5 (pls. 620 and 628), 528.1 (pl. 624), 527.6 and 528.6 (pls. 621 and 629), 544.11 (pl. 694), 523 (pl. 584). See also Night Thoughts watercolors (1794-97) no. 52 (“headlong Appetite” with Conscience, engraved [1797] as p. 27), no. 60 (the vision of Belshazzar when “high flusht with Insolence, and Wine,” engraved as p. 33), no. 68 (the Good Samaritan, engraved as p. 37), nos. 69, 152 (one of the misguided souls “who push our Antidote [Faith] aside”), no. 185 (the Soul rejecting “Earth’s inchanted Cup”), nos. 271, 289, 331, 345 (“Mystery” with her rummer of fornication), no. 380 (“A thousand Demons lurk within the Lee”), nos. 409, 479 (“A Banquet . . . where Men, and Angels, meet”)—in William Blake’s Designs for Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, ed. D.V. Erdman et al. (1980). See also Gray design (1798) p. 128 in Irene Tayler, Blake’s Illustrations to the Poems of Gray (1971). See also the Canterbury Pilgrims engraving (1810) (the wife of Bath) in R.N. Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake (1983), pl. 38. See also Dante design no. 89 (1824-27) (“The Whore [of Babylon with her rummer of abominations] and the Giant”) in A.S. Roe, Blake’s Illustrations to the Divine Comedy (1953). See also “Laughing Song” in Songs of Innocence (1789), pl. 15. An “Important silver mounted glass bowl” distantly related to a rummer “engraved round rim ‘William Hogarth to Dr. Samuel Johnson 1762’ ” is reproduced in The Antique Dealer and Collectors’ Guide (June 1959), p. 9. to indicate celebration or inebriation or dedication. Usually of course they imply debauchery, as in the engraving of “headlong appetite,” with rummer in hand, watched by Conscience for Young’s Night Thoughts (1797) p. 27 (illus. 2) and in that of Belshazzar, “high-flush’d with insolence and wine,” overturning his rummer, “amazed,” as he sees the hand writing on the wall, for Night Thoughts, p. 33 (illus. 3). A rummer is standard equipment for Blake’s Whores of Babylon (see Night Thoughts watercolor no. 345 and Dante design no. 89), presumably containing abominations and fornications, but it is also the vessel proferred by the Good Samaritan (Night Thoughts watercolor no. 68) or one which contains faith (Night Thoughts watercolor no. 152) or a utensil at a banquet of men and angels (Night Thoughts watercolor no. 479). Clearly the rummer does not invariably imply wine or abomination in Blake’s designs before and after 1800—it is merely a drinking vessel whose significance derives from its use.

DESCRIPTION

Size: Height 14 cm., diameter of bowl 10.5 cm.

Materials: English lead glass bowl and stem. Under ultra-violet light, the glass shows white, indicating the use of lead in its manufacture and pointing to Britain as its source; had it shown yellow, it would have implied a Continental origin of the glass. Air bubbles from bits of melted “stone” and striations in the body of the bowl are characteristic of early nineteenth-century glass.

The foot is of copper with traces indicating that it was originally silvered, and below the foot is a paper shagreen lining. The foot could have been broken and replaced at almost any time after the glass was made, but the worn silver on the replaced foot indicates that it is of some age. The glass itself is neither uncommon nor valuable, and obviously it would scarcely have been worth repairing unless it had sentimental value (“it was Uncle George’s”), or was needed to complete a set, or was especially treasured because of the inscription or design. The copper foot is comparatively inexpensive and ugly, suggesting either that it was not thought worth spending much money to restore the rummer to usable, standing condition or that there was not much money to spend. The technique of using copper for such a purpose is old and well known, and the material and method seem to imply no hint of date.4↤ 4 Pickering & Chatto in their catalogue say that the “Foot [was] replaced . . . probably late [in the] 19th Century,” and they attach some importance to the date but provide no evidence for it, and I have none to indicate that the foot could not have been replaced in this century—though I agree that it looks old, worn, and somewhat shoddy.

Shape: Tulip bowl on a short stem, with a “bladed knop or collar,”5↤ 5 Hayes, p. 202. and a simple circular foot.

begin page 95 | ↑ back to topEngravings: On one side of the bowl, most easily seen through the glass from inside the bowl: a faint design of a nude angel with his right arm outstretched, the left wing fully feathered, the right wing scarcely visible (illus. 12 in Essick, above).

On the other side, rather crudely scratched in the glass:

THOU HOLDER OF IMMORAL DRINK

I GIVE THEE PURPOSE NOW I THINK

(illus. 1)

On the collar:

BLAKE IN ANGUISH AUG 1803

(illus. 10-11 in Essick, above)

History: (1) Sold by an anonymous owner6↤ 6 A letter from me to the owner, forwarded by Christie’s in August 1983, has not been answered. For assistance with technical information, I am grateful particularly to Brian A. Musselwhite of the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) and to Roger Gaskell and Christopher Edwards of Pickering & Chatto Ltd. (17 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5NB) for showing me the Felpham Rummer in July 1983. in a miscellaneous sale of English and Continental Glass at Christie’s (London), 2 November 1982, lot 68 (not reproduced, described as decorated “in the manner of William Blake,” estimate £50-£100) for £55 to (2) Pickering & Chatto, who offered it in their Catalogue 651: A Miscellany of Rare and Interesting Books and Manuscripts ([March] 1983), lot 1 (“in a new display box in Pickering green morocco”) for $45,000.

Techniques of incision: There are a number of ways

of incising glass.7↤ 7 A method patented in 1806 gave the appearance of incising the glass, but in fact a permanent ground of powdered glass paste was added to the surface, giving a frosted appearance, and then partially removed, so that the designs, etc., are in the superficial ground and not in the glass (see Wakefield, p. 28 and pl. 29A). But this is not the method used in the Felpham Rummer, whose glass is transparent, not frosted or opaque. (1) One is engraving with a diamond tip, which leaves chips of unequal depth, and this was a common method. The Dutch were leaders in the field, though often they worked with glass made in England. “No particular training was necessary to produce a good engraving with a diamond point. Any one who was accustomed to engraving on metal . . . might be able, with a little practice, to produce reasonably effectively with the diamond point on the strong English glass.”8↤ 8 Buckley, p. 75. The lettering on the Felpham Rummer is fairly plainly incised at irregular depths with a diamond tip not unlike a conventional book-engraver’s tool.(2) Wheel engraving on glass was developed especially in Germany and was brought to England about 1727.9↤ 9 Buckley, pp. 42, 48. It was, however, not much used commercially in England until the 1830s, and as late as 1850 it was still experimental.10↤ 10 Wakefield, pp. 41-42. It was only suitable for heavy glass, but the English were not very good at it.11↤ 11 Hayes, pp. 120, 123. “By far the greatest number of glasses were decorated by the wheel process, which proved the most important one for artistic and conventional ornamentation.”12↤ 12 Davis, p. 84. In wheel engraving, “the finished vessel [is pressed] against the edge of a swiftly working wheel . . . the wheels are minute, some of them not reaching a fraction of an inch in diameter

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

(3) The third conventional method is etching in the ordinary way, adapted for curved surfaces. The chief problem for an etcher of copperplates would probably have been to discover an acid appropriate for etching on glass. The standard acid for etching copper, the mordant probably used by Blake’s master James Basire and by Blake himself, was aqua fortis composed of “vinegar (acetic acid), salamoniac (ammonium chloride), . . . salt,

and verdigris (an acetate of copper).”15↤ 15 Robert N. Essick, William Blake Printmaker (1980), p. 16; an unlikely alternative recommended by [Robert Dossie], The Handmaid to the Arts (1764), II, 146-50, is “nitric acid made with ‘spirits of nitre and vitriol.’ ” The acid necessary for etching on glass, however, was quite different, a hydrofluoric acid,16↤ 16 Davis, p. 84, says, “the first use of the hydrofluoric acid technique is said to have emanated from Germany . . . [where it had been discovered] towards the end of the 17th century,” but “Acid-etching was not seriously developed in this country [England] until the mid-19th century” (Crompton, pl. 170). directions for which were given in Rees’s Cyclopaedia (and doubtless in similar terms elsewhere): ↤ 17 Anon., “Glass,” Cyclopaedia, ed. Abraham Rees (1820; originally issued 1802-1819), Vol. XIII, f. 3Z2v (a reference pointed out by my friend Robert Essick). Note that the Cyclopaedia directions are for etching on flat surfaces to be “printed by means of the rolling press” and that the specifications for “a cover of metal or wood . . . [to] be laid over, and fitted close on the border of wax, to keep in the fumes of the acid,” and for the border of wax, are presumably irrelevant to the process of etching on a curved surface.Etching on Glass, is performed in the following manner: Lay a thin coat of white wax (as etching ground is laid) on the plate of glass. On this the drawing must be traced in the usual way. When the subject is etched, a border or wall of wax of a very even height must be put around [as Blake did for his relief etchings]: taken then some fluor spar powdered to about the fineness of oatmeal, and strew it evenly over the etching, and on this pour a mixture of equal quantities of sulphuric acid and water, till the whole is about the consistence of thick cream. . . .It seems likely enough that formulae for acids designed to etch on surfaces other than metal were common knowledge among professional engravers and that, at the very least, plausible mordants could be discovered

If the subject be to be etched with care, and high finishing be required, the acid mixture must be taken off occasionally, and the plate, after being well washed and dried, must have the parts that are bit-in enough, stopped-out, as in common etchings, when the mixture must be again put on, . . . and this must be repeated till the several gradations of shade are believed to be sufficiently corroded.17

The chief novelties for Blake would probably have been how to get the acid to bite uniformly over a curved surface, how to get the acid the right strength for glass, and how long to allow it to bite. With etching on copper, one tests one’s progress by taking a proof on paper, but with glass the design in the solid surface is the end itself, rather than the means to the end (printing the design on paper). Someone experimenting with the process is likely to use comparatively weak acid formulae and short bites, to etch lightly at first, to see how the process works.

The angel in the design on the outside of the bowl bears the stigmata of an experimental etching. The depth of the incisions is of a uniformity virtually impossible to achieve with engraving in the ordinary way, by chipping with a diamond point or wheel engraving. The incisions are very shallow and are so faint as to be difficult to see even when holding the object in one’s hands and turning it to the light to catch the refraction from the incisions. And one side of the design, the angel’s right wing, is almost invisible, suggesting either that it was never completed in the drawing at all or that, if drawn, the acid did not bite there effectively—a problem perhaps caused by the curved surface.

Designs on rummers are usually heads of the famous or of patrons, or symbols of drink such as grapes, or pastoral scenes or elegant houses or ships. The design of the angel here is of course not peculiar to Blake—many artists of the time might have designed similar angels, artists such as Fuseli, Stothard, Barry, and Westall. On the other hand, Blake made similar angels; that in Night Thoughts watercolor no. 341 (illus. 4) is very like that on the Felpham Rummer, and the shape is repeated elsewhere, as in Job (1826) pl. 14. The design on the Felpham Rummer could well be his, allowing for the experimental character of the shape in an unfamiliar medium.

The lettering is scratched on somewhat crudely in diamond point. All the lettering seems to be in the same hand. Since no other work on glass by Blake is known, we may presume that the medium was unfamiliar to him. It is therefore very likely that, if he were writing thus on glass, the style would not much resemble his own18↤ 18 Or rather any of his own. In Upcott’s Autograph Album, Blake wrote: “I do not think an Artist can write an Autograph[,] especially one who has Studied in the Florentine & Roman Schools[,] as such an one will Consider what he is doing but an Autograph as I understand it, is writ helter skelter like a hog upon a rope” (William Blake’s Writings [1978], p. 1321). Blake had numerous styles of lettering, from the most beautiful copperplate hand to hurried, almost illegible scrawls. —and in fact, the style is very conventional and anonymous, with stick capitals throughout and some difficulty with curved lines. Considerable trouble was experienced with the N, but the T, H, E, F, and K have some degree of elegance, with deft little flourishes at the ends of lines, and the curious G is not un-Blakean. One could scarcely say that the form of the writing is much like that which Blake made with pen, brush, pencil, graver, or etching needle—but, on the other hand, it is not significantly inconsistent with his either, if one bears in mind the unfamiliarity of the medium.

The language of the couplet is certainly not characteristically Blakean. Most of the words which are in any way unusual—“holder,” “immoral,” “drink” as a noun, “give . . . purpose”—do not appear in Blake’s previously recorded vocabulary, or appear only in different senses. The noun “drink” is not uncommon in Blake,19↤ 19 A Concordance to the Writings of William Blake, ed. D.V. Erdman et al. (1967). but it never seems to have elsewhere the pejorative alcoholic connotation it clearly bears here. Neither “holder” nor “give . . . purpose” is found elsewhere at all, and the only use of “immoral” is not pejorative: “the grandest Poetry is Immoral[,] the Grandest characters Wicked.”20↤ 20 Annotation (?1800) to Boyd’s translation of Dante (1785) in William Blake’s Writings (1978), p. 1447. Only the use of “immoral” in the couplet gives one much cause to pause, for Blake does not use forms derived from it at all (e.g., “immorality”), and ordinarily he avoids moral questions: ↤ 21 William Blake’s Writings, p. 664. ↤ 22 William Blake’s Writings, p. 929. ↤ 23 William Blake’s Writings, p. 1056.

If Morality was Christianity Socrates was the Saviour.21It would certainly be surprising to find Blake using “immoral” as it appears on the Felpham Rummer—but then almost everything Blake did is surprising.

. . . Satan first the Black Bow bent

And the Moral Law from the Gospel Rent.22

The Moral Christian is the Cause

Of the Unbeliever & his Laws.23

The attitude toward “immoral drink” is also surprising, for Blake himself had no aversion to drink or to pubs: ↤ 24 Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Blake. “Pictor Ignotus” (1863), I, 313-14, quoted in Blake Records (1969), pp. 307, 308.

he fetched the porter for dinner himself, from the house at the Corner of the Strand [near where he lived 1821-27]. Once, pot of porter in hand, he espied coming along a dignitary of Art—that highly respectable man, William Collins, R.A., whom he had met in society a few evenings before. The Academician was about to shake hands, but seeing the porter, drew up, and did not know him. Blake would tell the story very quietly, and without sarcasm. . . . It was only in later years he took porter regularly. He then fancied it soothed him, and would sit and muse over his pint after a one o’clock dinner. When he drank wine, which, at home, of course, was seldom, he professed a liking to drink off good draughts from a tumbler, and thought the wine glass system absurd. . . .24

The justification for the attitude toward “immoral drink” must come, if at all, from the events of August 1803. Blake was then living at the little seaside village of Felpham, and he must have gone repeatedly to the local gossip center, The Fox Inn fifty yards from his cottage, for his landlord was also the proprietor of The Fox.25↤ 25 Blake Records, p. 561. During the invasion hysteria of the summer of 1803, a troop of Royal Dragoons was quartered at The Fox, and the public bar must have been full of soldiers. On 12 August Blake had a violent quarrel with a soldier named Scolfield whom he found unexpectedly in his garden, and, as he wrote in his account of the incident, “Mr. Hayley’s Gardener came past at the time of the Contention at the Stable Door [of The Fox Inn], & going to the Comrade [Private Cock] Said to him, Is your Comrade drunk?—a Proof that he thought the Soldier abusive, & in an Intoxication of Mind.”26↤ 26 Blake Records, p. 127. Blake may well have known then what his attorney Samuel Rose begin page 98 | ↑ back to top said at his subsequent trial for sedition, that Scolfield had been “degraded on account of drunkenness” from the rank of Sargeant.27↤ 27 Blake Records, p. 142. In “AUG 1803” Blake was certainly “IN ANGUISH,” and he may well have had reason to believe that the perjured evidence against him was manufactured by Private Scolfield partly because of his indulgence in “IMMORAL DRINK.” It is imaginable that this rummer is from The Fox Inn and even that Private Scolfield or his accomplice Private Cock had drunk from it. Blake must have had to go to The Fox Inn after the incident in order to collect evidence with which to defend himself before the magistrates on 15 August or at his subsequent Quarter Sessions trial on 4 October, and it is at least conceivable that he scratched the couplet, date, and signature on the rummer with a borrowed diamond in a few minutes on such an occasion. (Among his local acquaintances, only his patron William Hayley and their friend Henrietta Poole are likely to have had a diamond.)

The etching could not have been done so casually—even professional engravers like Blake do not ordinarily carry wax and etching acid in their jacket pockets. If the angel is by Blake, it was probably made at his cottage, as an experiment quickly abandoned. Or perhaps the sequence was reversed—perhaps the landlord of The Fox, wishing to profit from the presence in the village of a tame artist and engraver, had asked Blake to decorate the pub rummer with an angel and Blake had the unfinished vessel in his cottage on August 12th when he emerged to find Private Scolfield in his garden “drunk . . . abusive, & in an Intoxication of Mind.” In such circumstances, it would not be astonishing to find him returning, after the excitement had diminished a little, to add the words to the rummer. Certainly he was writing such anguished and indifferent couplets in his Notebook at about the same time: ↤ 28 William Blake’s Writings, p. 947. ↤ 29 William Blake’s Writings, p. 946.

On H—

Thy Friendship oft has made my heart to ake

Do be my Enemy for Friendships Sake28

When H—y finds out what you cannot do

That is the very thing he[’]ll set you to29

Are the etching and engraving by Blake? The glass may well have been made before 1803—certainly the style of rummer was popular long before then, the glass seems to be British rather than Continental, and the quality of the glass suggests it was made about 1800. The inscriptions were scratched and the angel etched by techniques familiar to Blake, though the material was strange and therefore difficult. We should not expect to find his very personal hand strongly marked in either words or design, even if he made them. The biographical context is right, and on other occasions Blake certainly made poems and designs as puzzling and indifferent as these. The chief grounds for doubt are the curious material, the very troubling lack of history before 2 November 1982 (an obscurity which the previous owner seems to be unwilling to dissipate), and the reference to “IMMORAL DRINK,” a reference apparently explicable only in terms of the biographical context.

Of the various possibilities to be considered—forgery, memento, copy, adaptation, and original—copy and adaptation seem unlikely, since no original significantly like this in any way is known. The possibility that it is a memento, made by a friend at the time or later, is also negligible, for there was no other etcher in Felpham at the time, and no artist friend of later years is likely to have had the biographical information as well as the inclination to make it. It could of course be a forgery,30↤ 30 Pickering & Chatto say in their catalogue: We have, of course, considered the question of authenticity very carefully. The hypothesis of forgery would require it to have been carried out before 1900, that is, before the repair to the foot, for no-one at that time would have bothered to repair an ordinary pub rummer, if it had not already been engraved. At that time, a forgery could have had little commercial justification. It would have required the skill to forge a Blake drawing of an angel, to forge Blake’s lettering by a separate method of engraving, to invent a metrically correct two-line Blake poem, in the right style of that period of his life, and biographical knowledge to invent and date the inscription, information which was probably [sic] not available before the publication in 1926 of the [16 August 1803] letter to Butts. In our view, forgery can therefore be eliminated as a possibility. However, much of this evidence seems to me weak. There is no solid evidence that the foot was repaired by 1900; a repair might have been made at any time for reasons other than preservation of the inscriptions; imitations of Blake were in any case made before 1900, such as those by Camden Hotten (see M.D. Paley, “John Camden Hotten, A.C. Swinburne, and the Blake Facsimiles of 1868,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 79 [1976], 259-96, and “A Victorian Blake Facsimile,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, 15 [1981], 24-27), and there are reasons for repairing it other than commerce. The skill in creating the design and poem is not formidable (“metrically correct” may be the poem’s highest praise), and the biographical information was available in Gilchrist in 1863 (Vol. II, pp. 196-98), long before 1926. Forgery therefore should not be “eliminated as a possibility,” though I agree that it is somewhat improbable. made at almost any time between 1863, when Gilchrist’s Life resurrected Blake’s reputation, and 1982, but, if so, the modesty with which it was introduced into the market was scarcely likely to bring its creator much profit—if indeed he still had it to profit from. All the tests concerning date, place, and technique for a modern fake have proved negative; date, place, and technique may all have been accessible to Blake. On balance, it seems to me probable that the couplet, the signature, and the angel are all by Blake.

If so, the significance[e] of the Felpham Rummer is not what it adds to our knowledge and suppositions of Blake’s poetry and art, but what it suggests about the ANGUISH he felt in August 1803—and the immediacy with which he expressed his anguish in poem and design. And the ambivalence in his attitudes towards DRINK and IMMORALITY suggested by the couplet are worth bearing in mind. If the couplet is his, we must be more cautious in our conclusions about Blake’s views of morality. The allegation that it is the artist who gives purpose to objects is very Blakean, but the attribution of immorality has not previously seemed to be so. The Felpham Rummer, like most “Blake” discoveries, seems to raise more questions than it answers—and this, at least, is a very Blakean quality.