MINUTE PARTICULARS

Visual Analogues to Blake’s “The Dog”

Apart from the poetic text it was meant to illustrate, Blake’s frontispiece to one of William Hayley’s Ballads, “The Dog,” appears to have two curious visual analogues in a caricature by James Gillray and an emblem by the sixteenth-century Hungarian emblem writer, Joannes Sambucus. While the primary impetus for the frontispiece comes, of course, from Hayley’s poem, its affinities with the emblem and caricature suggest that the earlier works had some influence on Blake’s illustration (or perhaps, even on Hayley’s ballad itself). The pictures in question deal with vastly different issues: the Blake focuses on a little dog’s faithfulness; the emblem, entitled “Sobriè Potandum,” or “we must drink soberly,” warns against the evils of drunkenness; the caricature, called “The Republican Rattle-Snake Fascinating the Bedford Squirrel,” mocks the relationship between two contemporary English politicians, Charles Fox and Francis Russell, fifth Duke of Bedford. Yet all these designs share the basic feature of a reptilian beast laying snares for the unwary, and in the case of Blake and Gillray, of such a beast about to devour an animal falling toward it.

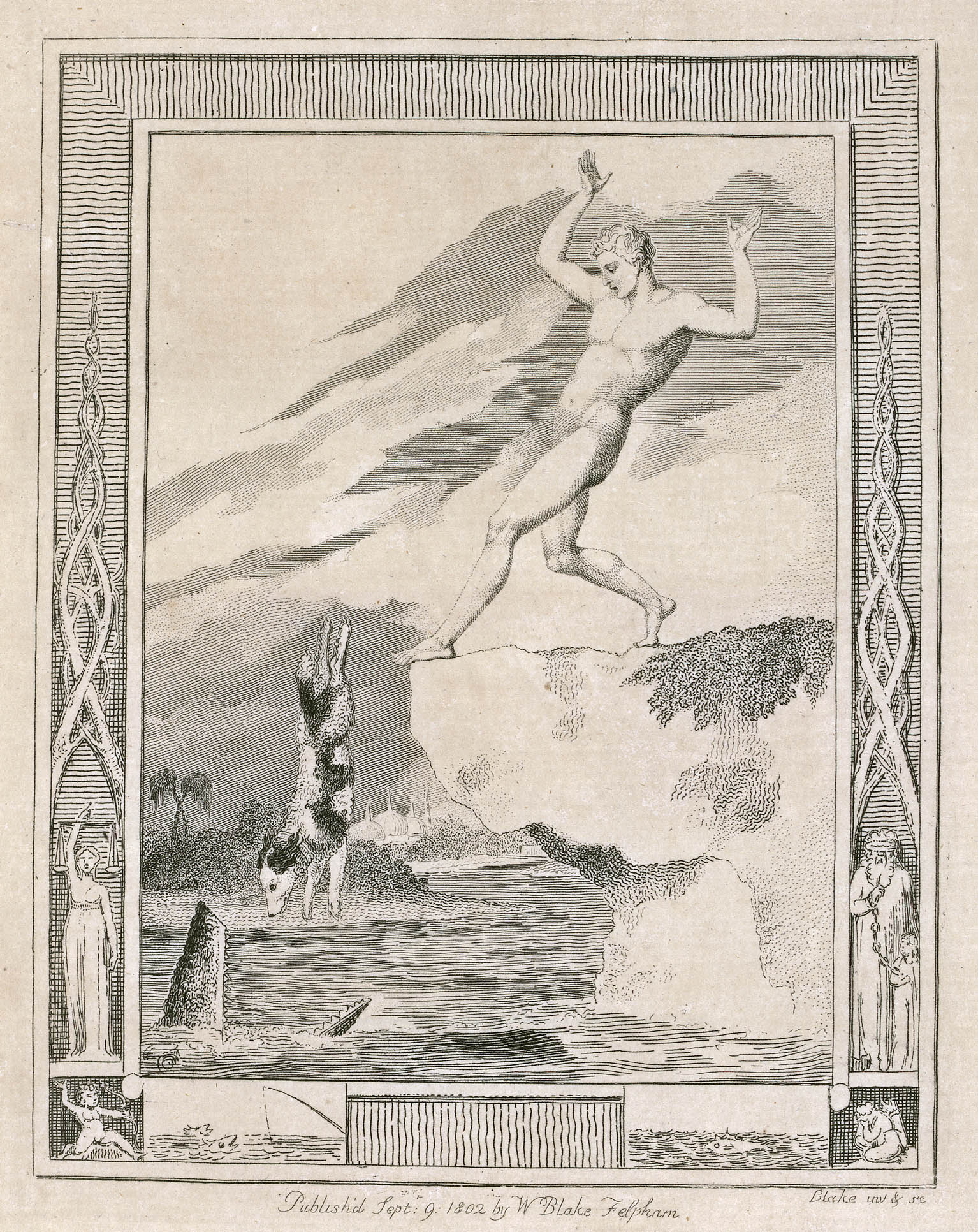

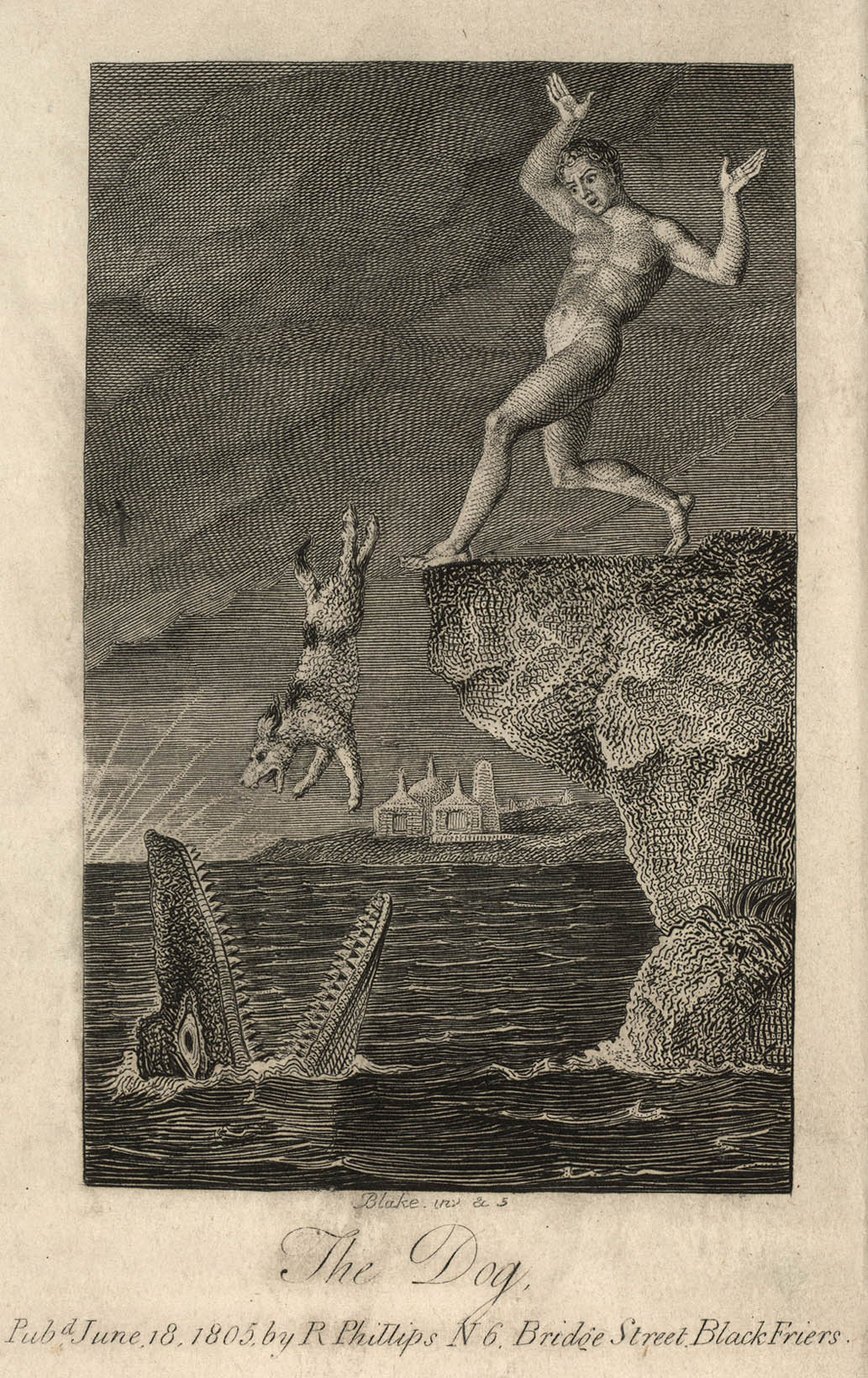

Blake’s design takes as its subject the climactic moment in Hayley’s sentimental ballad. Here the faithful Fido, as Hayley calls him, seeing his young master about to dive unwittingly into a crocodile’s watery lair, saves the youth by deliberately leaping ahead of him into the jaws of the waiting crocodile. The specific lines Blake depicts are as follows:

His faithful friend with nobler pace,(The lines given are those of the 1802 version; in 1805, lines 65-66 were slightly altered: “nobler” was changed to “quicker,” while “not” was changed to “now.”) Blake’s illustrations for these verses in both the 1802 and 1805 editions of the Ballads1↤ 1 William Hayley, Designs to a Series of Ballads (Chichester: J. Seagrave, 1802); and William Hayley, Ballads . . . Founded on Anecdotes Relating to Animals (Chichester: J. Seagrave, 1805). For detailed physical descriptions of the designs, see David Bindman, The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake (New York: G.B. Putnam’s & Sons, 1978), pp. 479-80, and Roger R. Easson and Robert N. Essick, William Blake, Book Illustrator (Normal, Illinois: American Blake Foundation, 1972), I, 31-35, 41-44. For a full account of the entire Blake-Hayley Ballads project, see G.E. Bentley, Jr., “William Blake as Private Publisher,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 61 (1957), 539-60; G.E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), pp. 88, 92-98, 100-02, 157-62; and Robert N. Essick, William Blake, Printmaker (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), pp. 169-73. take essentially the same form—we see the canine hero spreadeagled in the air, as he hurtles kamikaze-fashion toward the crocodile’s cavernous maw; meanwhile his startled master, seeming to brake himself just in time, looks down from the safety of the cliff on the dismaying scene below (illus. 1 and 2). For the 1805 edition, Blake engraved a smaller version of the 1802 picture, eliminating the fanciful border of the earlier engraving, adding the title, “The Dog,” and changing various details in the background as well as in the positions and expressions of the dog, crocodile and youth. Some of these changes render the 1805 version more dramatic than the earlier design. In 1805, the fierceness of the confrontation between dog and crocodile is intensified by their jaws being more bared—Fido is shown barking (or at least snarling), while the crocodile is less submerged, thus revealing more of his fearsome teeth.2↤ 2 Curiously, Blake’s 1802 illustration of a non-barking Fido fits Hayley’s 1805 text more closely than it does the earlier text, for in 1805 Fido is described as leaping “now with silent tongue”; the 1805 design, however, shows Fido as he was described three years before, “not with silent tongue.” In the later design, the increased height of the cliff makes Fido’s leap seem all the more courageous. We also see more of Edward’s face in 1805, and Blake has endowed his features with greater anguish. Uninspired as the designs remain, these alterations not only increase the drama of the scene, but also accompany a general improvement in the quality of the Ballads illustrations. As Robert N. Essick observes, “The five

And not with silent tongue,

Outstript his master in the race,

And swift before him sprung.

Heaven! How the heart of Edward swell’d

Upon the river’s brink,

When his Brave guardian he beheld

A glorious victim sink!

(William Hayley, “The Dog,” 11.65-72)

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

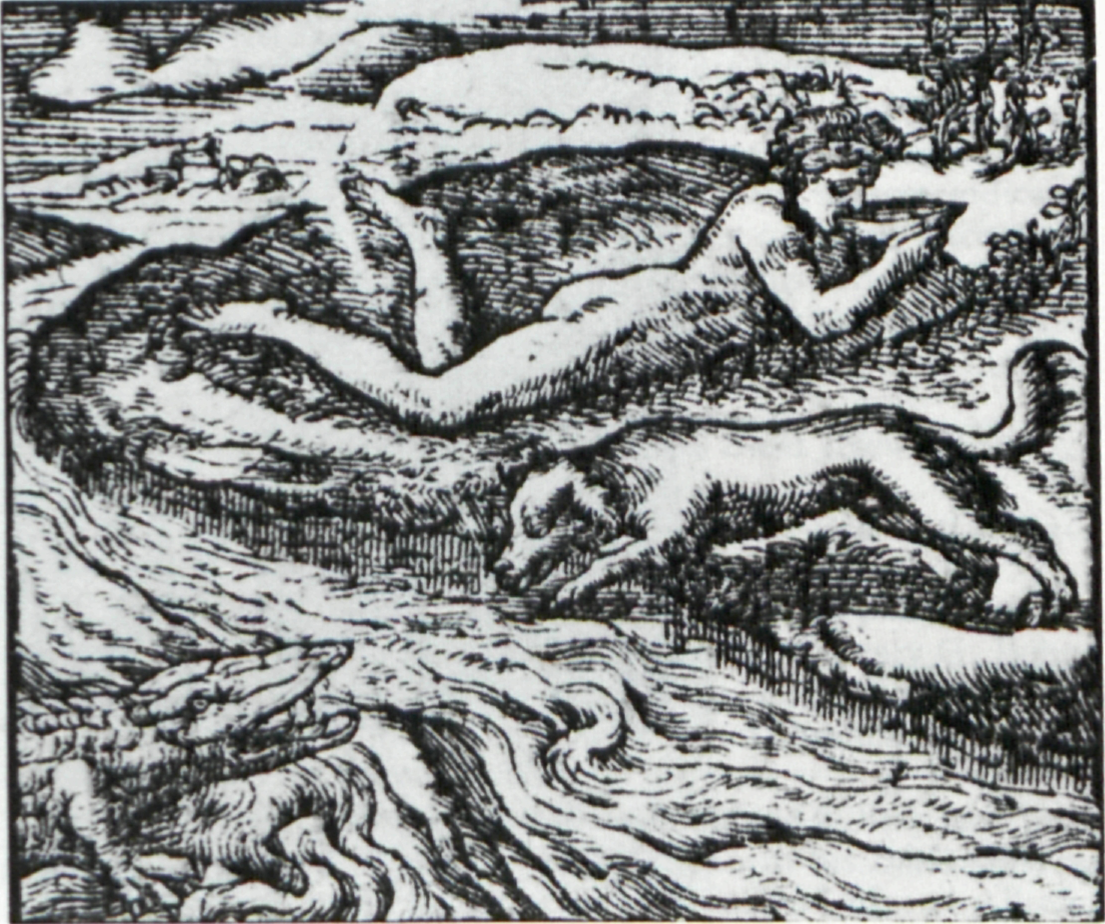

If we turn from the Blake line-engravings to the emblem by Sambucus (number 41 in Sambucus’ Emblemata, Antwerp, 1564, reproduced exactly as number 125 in Geffrey Whitney’s A Choice of Emblemes, Leyden, 1586), we may be surprised to find the same cast of characters as in Blake and Hayley—a nude young man, a dog, and a threatening crocodile (illus. 3). Sambucus’

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Given these parallels, it is not unreasonable to suppose that Blake was familiar with Sambucus’ emblem, either through Sambucus’ own Emblemata, or what is more likely for a late eighteenth/early nineteenth-century British artist, through the famous anthology, A Choice of Emblemes, compiled by the Englishman Geffrey

Less strikingly similar to the Blake but still suggestive of it in composition is Gillray’s colored engraving, “The Republican Rattle-Snake Fascinating the Bedford Squirrel.” Published 16 November 1795, Gillray’s caricature depicts the Whig leader Charles Fox as a huge rattlesnake coiled around an oak tree. Falling out of the tree in a pose quite like that of Blake’s self-sacrificing Fido, and heading directly toward the snake’s open mouth, is a squirrel with a human head—that of the Duke of Bedford (illus. 4). The picture, on a topic dear to Gillray, satirizes “the political influence by Fox over Francis, Duke of Bedford, who had become one of the most zealous of the popular party.”8↤ 8 Thomas Wright and R.H. Evans, Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1851), p. 70; see also M. Dorothy George, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires (London: British Museum Publications, Ltd., 1978), 7, 198. Despite obvious differences, the genuine similarities between Gillray’s engraving and Blake’s design (the small animal in midflight falling into a reptile’s mouth, the reptile with open jaws, gazing upwards) lend support to the view that Blake was sufficiently well acquainted with Gillray’s work to echo certain of the caricaturist’s motifs in his own art.9↤ 9 Intriguing connections between Blake and Gillray have been convincingly presented by David V. Erdman in his Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 2nd ed. rev. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), pp. 203-05, 218-19, and by Nancy Bogen in her “Blake’s Debt to Gillray,” American Notes & Queries, 6 (Nov. 1967), 35-38. For an earlier version of Erdman’s discussion, see “William Blake’s Debt to Gillray,” Art Quarterly, 12 (1949), 165-70. While in some instances such echoes seem intentional (as demonstrated by Nancy Bogen—see note 9), there is no evidence of a conscious imitation of Gillray in “The Dog.” Yet perhaps the similarities are not purely coincidental. Indeed, the parallels between Blake’s illustration and the Gillray cartoon could partly stem from Blake’s unconscious absorption of Gillray’s composition long before Blake ever knew he was going to illustrate a poem about a dog and a crocodile.

The analogues we have explored here provide further evidence of Blake’s links to Gillray and to the emblem tradition. Continued investigation of popular art forms such as emblem books and caricatures will doubtless tell us still more about the breadth of material assimilated by Blake and recast in his own designs, even when those designs exist primarily to illustrate the words of others.