article

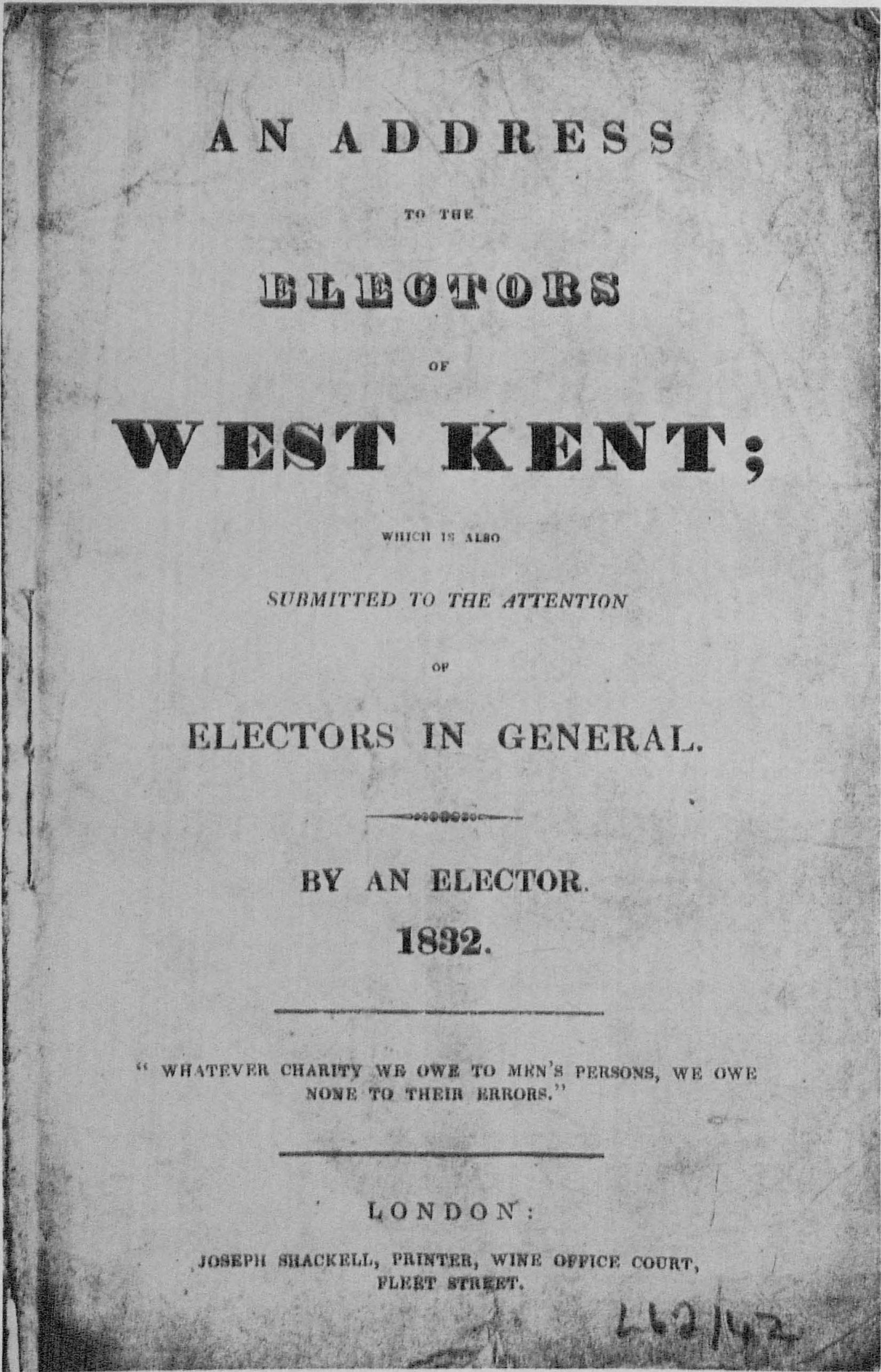

begin page 60 | ↑ back to topAN ADDRESS TO THE ELECTORS OF WEST KENT.

My Lords and Gentlemen ;

An individual, who has the honour to be of your number, ventures to address you on the subject of the approaching election; and entreats you to afford him a few moments’ serious attention; which he claims, not for himself, but for the importance of his subject.

Sir William R. P. Geary comes forward, and offers himself as your Representative; promising an assiduous attention to Parliamentary duties. He will strenuously support the agricultural interest; and such a modification of the tithe laws as may comport with the security of all other kinds of property. He will also promote, to the utmost of his power, every rational, effective and substantial reform. He comes from the heart of the county; and from his family and connections, we cannot but believe him to be a lover of agriculture; an interest now upon the very verge of destruction. Sir William is an INDEPENDENT CANDIDATE, and the son of a late INDEPENDENT MEMBER.

Surely no person connected with the agricultural interest, and solicitous for the welfare of this great county, can for a moment lend his influence to the opposing faction, who denounce the protecting duties as a “Bread Tax,” and taunt Sir William with a desire of continuing it. Now as every Kentish farmer, who is in his right wits, conceives some sort of “Bread Tax” to be the very condition of his existence, how could our adversaries be so very simple as to tell him plainly, that his only chance of preserving it was by voting for Sir William Geary? However, as they have been so kindly explicit, I hope, like men of common sense, we shall take them at their word, and vote for Sir William, as they advise. Their hostility to Agriculture, which could not long be concealed, notwithstanding any professions they might have made to the contrary, sufficiently bespeaks them to belong to the caste of the Radical Reformers, MOST FALSELY SO CALLED; who are the natural enemies of the farmer, and, by consequence, of the manufacturer; for commerce and agriculture must stand or fall together;—and, therefore, of all national prosperity.

One is almost tempted to believe that some cunning Agriculturist, in disguise, drew up their manifesto, and laughed at them in his sleeve; for certainly it is its own best refutation. Sir William Geary has promised to support the Agriculturist; and this is the very reason for which agricultural Kent is called upon to repudiate him! Risum teneatis. Rome was saved by the cackling of geese: and truly, if the jacobinic citadel might be preserved by similar multitudes, it must be acknowledged to be impregnable!

Thus have they forfeited the support of all sensible farmers; and at the same time disgusted every honest man, whether Whig or Tory, by retailing, in the true spirit of jacobinism, a falsehood respecting the income of the Church, so outrageous; that it looks like a droll burlesque and caricature, even of the flagitious system of misrepresentation and imposture, by which that profligate faction is supported.

With respect to the Candidates themselves, who have been unitedly soliciting your suffrages; nothing can be farther from the writer’s intention than to offer them personal disrespect: he would be the first to yield them that deference which all gentlemen have a right to claim from each other in private society: but he feels it his duty to speak very plainly of the faction whose support those gentlemen have deigned to conciliate.

Another objection to Sir William is his youth. It is said, “We want men of experience in Parliament:” But, beside that often one man of thirty will be found wiser than another of seventy; that multitude of years does not always teach wisdom: that every profession affords numerous instances of the young attaining honours and distinction; and of aged men who could never rise from mediocrity; and that some of our most splendid public characters have signalized themselves when but scarcely out of their minority: how, we should be glad to know, are we to obtain Representatives of great Parliamentary experience, unless by sending them in betimes, we give them an opportunity to acquire it? If we return none but old men, we defeat that object entirely; and our Council of Ancients must ever be a bench of venerable novices. But, above all, I would ask, is it not most expedient, that in the great senate of a nation there should be found the energy and fire of youth, as well as the deliberative sagacity of age? The parents of all sublime works are Intellect and Will.

Some have strangely refused to support Sir William Geary, on account of their being, from early associations, attached to the Whigs. Alas! it is but an ill compliment to the Whigs of sixteen hundred and eighty-eight, to mistake for their successors a rabble of incendiaries and jacobins. The politics promulgated by our adversaries are not those of MARLBOROUGH or CHATHAM, but of THISTLEWOOD and BRAN-DRETH!

NO! Brother Electors!—The Radical upas tree never sprouted from the stock of ancient British Whiggism; begin page 62 | ↑ back to top but it is the importation of yesterday, from poor, degraded, dishonoured, Atheistical France.

That once gay nation long led the mode in our more innocent fripperies of dress and fashion: we amused ourselves with her toys and trinkets; and with perfect good humour saw her play the Harlequin to Europe. But she rose in our estimation, when she began to struggle against aristocratic tyranny. She obtained her freedom: and, alas! immediately lost it again, irretrievably; by confiding it, as the people of England are at this moment confiding their own—to revolutionary empyrics. Then, when suddenly distracted with an infernal phrenzy, her songs and dances became the yells and contortions of possession; and, in a frantic spasm, she hurled over the Continent fire-brands, arrows, and death: who, with more alacrity than the Kentish patriot, sprang forward, and bound the demoniac?

And shall we, even now, bitten with that selfsame madness; while, though somewhat exhausted with her paroxysm, France yet heaves in incurable distraction; shall we mistake her ravings for the voice of Delphic Sibyl; and proceed to model, or rather unmodel, every institution of our country, and tumble them all together, into the semblance of that kingless, lawless, churchless, Godless, comfortless, and most chaotic Utopia of French philosophy?

Shall we assay to repair here and there a crumbing pinnacle of our Constitution, by cannonading the buttresses and sapping the foundations?

Shall we invite over the Gaul to help us raze those bulwarks, which he too well knows to be thunder-proof; and put up a pagoda of trash and tinsel on the site?

But now, behold, you are called out, Men of Kent—yes, YOU, whose frown has made the Frenchman shiver—to mince and caper in the ballet of liberalism; and to bring up the death-dance of Parisian assassins and sanscullotes!

They were the Men of Kent who dictated terms to the Norman Conqueror: and they are Men of Kent, who are now asked to become morally the vassals of France.

Who does not remember that crisis—God forbid any Englishman should forget it!—when Wordsworth sang,

“Ye men of Kent, ’tis Victory or Death!”

Then, even as one man, rose up this noble county; and with a front of spotless loyalty, scared Napoleon from our shore. O let not their degenerate children crouch to an invasion of much more fatal principles and doctrines.

The mane of the British Lion can receive no decoration from shreds of tri-coloured ribbon; nor will he cut any very majestic figure in the eyes of Europe, if we suffer our new-fangled politicians to retrench his tusks and talons; and to lead him about as a show, with the Monkey of French innovation mounted upon his back.

O my countrymen, for shame! for shame!—Methinks I see the mouldered heroes of Crecy and Agincourt, of Trafalgar and Waterloo rise up to hoot us from among the nations!

But let it be so no longer! Put on, once more, the invincible armour of old English, of old Kentish loyalty. Strangle the snake corruption wherever you shall find it; and every where promote, in God’s name, effectual reform: but leave not your hearths and altars a prey to the most heartless, the most bloody, most obscene, profane, and atrocious faction, which ever defied God and insulted humanity.

You will NOT suffer those temples where you received the Christian name to fall an easy prey to sacrilegious plunderers! You will NOT let that dust which covers the ashes of your parents, be made the filthy track of Jacobinical hyenas!

Farmers of Kent—we are tempted with a share of the promised spoliation of the CHURCH!—There was a time when every Kentish yeoman would have spurned at the wretch who should have dared to tickle him with such a bait—to offer him such an insult! But piety and honour are in the sepulchre.

I would fain hope, however, that there are still very few of us who would not experience some shudder of conscience, at the thought of thieving from the Church of England her freehold lands and tenements: few among the uncultivated; few among the vicious: few in our jails and halls: few anywhere, but within the precincts of our political unions. There are gradations even in atrocious felony. It is not every burglar who would violate an altar. But what are we to think of those vassals of perdition who would put forth their hands to the freeholds of the Church: who are not afraid to appear in the presence of their Creator branded with sacrilege! It is scarcely, perhaps, to be regretted, that these lepers are now catalogued, and marked, and numbered, and huddled together in the pest-house of the unionists.

So much for the Church lands. As to the tithe laws, they are about to undergo revision: perhaps very considerable alteration. Sir William Geary has offered to promote any amelioration; any equitable adjustment: nor can any one be more likely to watch the interests of the Kentish farmer closely, during the discussion in Parliament.

But there are some very honest and well meaning persons to be found, who imagine that an abolition of the tithe altogether would relieve the farmer from his present difficulties: who suppose that if the tenth sheaf were not put into the tithe waggon, the farmer would put the value of that sheaf into his own pocket; whereas nothing can be more false; because the tithe is always allowed for in the rent, which would be so much greater if there were no tithe. Land will always be let to the begin page 63 | ↑ back to top best bidders; and whatever men will give for a piece of land to-day, knowing it to be subject to tithe; they would give proportionably more for it to-morrow, tithe free; whether the tithe be a real tenth, or seventh, as some say; or whatsoever proportion it bears to the farmer’s returns.

Farmers! Messrs. Hodges and Rider are to attempt two things in behalf of their constituents. In the first place, they will sweep away the “Bread Tax,” that is, the protecting duties on foreign corn; which you know will utterly ruin you. But then, they tell you that they will try to abolish the payment of tithe: and who would not gladly be ruined, for the pleasure of seeing the tithe laws abolished! Now it is not unlikely that they may bring about a free trade in corn; because free trade is the fashion: but it is by no means so probable they will succeed in immediately abolishing the tithe, because that can scarcely be done without a revolution. Well; you know that a free trade in corn will throw the farms out of cultivation; starve the whole of the peasantry; and force many of you to emigrate from your native country for ever: but I will show you that the abolition of tithe, at the same moment, would not put a farthing into your hands, to defray the expences of the melancholy passage!

In all matters of sale and traffic

“—The worth of anythingA tithe-free farm fetches a proportionably high rent: therefore were all the farms tithe free, from the abolition of the tithe laws; all the farms would fetch a rental proportionably increased. What then would the farmer gain by it? Supposing the tithe were doubled: you would go [to] the landlord for an equivalent deduction in your rent—supposing the tithe abolished; he would come to you for an equivalent increase. Our mistake lies in not clearly understanding what it is that we rent of our landlord. We may, perhaps, imagine that we pay him for the whole of the crops which we produce; and that the tithe card takes away a tenth of that produce, for the whole of which we have made our landlord a consideration: but it is no such thing: we never paid for that tenth: it was not charged in our rent. In short, we pay our landlord for the right of disposing of nine tenths of the produce of his land; and if the other tenth were not removed by the tithe man the landowner would take care to demand it in rent. It is irksome to be put to the proof of anything so self-evident, where every argument is like a truism.

Is as much money as ‘twill bring.”

The best informed authors will inform us that the ancient landowners, who built most of our parish churches, left to their children only nine tenths of the profits of the estates which descended to them: the remaining tenth they bequeathed in the shape of the present tithe, to their respective churches for ever: and that bequest was and is ratified by the laws of our country. Therefore the landowner who is possessed of a thousand acres, receives only the profits of nine hundred: to-morrow, were the tithe law repealed, he would have ten hundred, bona fide disposable to his own use and benefit. Now when we can suppose our landlord not to be aware that a thousand acres are worth a higher rental than nine hundred, then indeed we may expect to be benefited by an abolition of the tithes!

The small tradesman and the poor would be losers indeed, by the proposed innovation: for the money which is in most cases spent and distributed among them by the clergyman’s family, would be often drawn away by absentee landlords, and spent at a distance from the parish, if not in a foreign land.

As to the very ancient triple distribution of the tithe, which has been spoken of in certain quarters; one part to the poor; another to the parochial clergy; and a third towards the repairs of the Cathedral; a moment’s reflection will convince us of its impractibility at present; when by the blessing of God our parish churches are so vastly multiplied; and I am happy to add, multiplying. The solicitude of the enemy for the beauty of our cathedrals is a little out of character: we may believe it to equal their sympathy for the poor: with respect to whom, be it remembered, that the clergyman pays his full share of poor-rate upon his income; to say nothing of the innumerable private charities, and neighbourly benefits conferred on their parishioners, by the great majority of that amiable and venerable, though most shamefully calumniated order.

But the landholder would, in effect, gain little more than the farmer, by the abolition of tithe: for, as the whole income of the Church, divided equally among her clergy, has been calculated scarcely to afford a decent maintenance to each; at least as much as was before levied in tithe, must then be imposed as a tax by government. So long then as the clergy should be decently supported, there would be no transfer of their incomes to the landed proprietor or to any one else. And if a revolutionary government were to ensue, and abolish our religious establishment altogether; which would be one of its first achiev[e]ments; the landholder will not be so simple as to believe that the Radicals would suffer him to sit down quietly with his increased rent: that is, supposing there were any rent to be had, after free trade had emptied his farms and exiled his tenants. No; they will tax him, and fleece him to the skin; and then confiscate his estates. The demagogue is the natural enemy of the landholders: for he finds in them at once the toughest obstacles to his ambition, and the most delicious temptations to his voracity. He will, therefore, spare no pains to decoy and devour them.

I will not attempt to adumbrate the gradations of begin page 64 | ↑ back to top slow torment, through which the crew of a triumphant political union would pare down the wretch who should fall into their clutches; condemned of that crime, in their estimation the most inexpiable; the possession of wealth. The spectacle of a whale under the hatchets of his harpooners; or rather of the South American Indian, made through a summer day the amusement of his captors, would present a lively type of the proceedings of these national anatomists with the catalogue of his possessions; and, perhaps, with the members of his person! I most humbly confess myself inadequate to do justice to that consummation of fraud, rapine, outrage, and barbarity, which may be expected from the Radicals of England, improving upon the example of the French Jacobins.

The British landholders are, however, too well aware of the motives of the Liberals, very readily to accept any boon from their hands. But, lest the people at large should be wired in a like gin; I shall take the liberty to exhibit before them, for a few moments, their French neighbours, gulled by the bait, and struggling in the toils: and it is then to be hoped that they will take care not to render themselves most forlorn exceptions to the general verity of the sacred proverb, that “the snare is surely spread in vain, in the sight of any bird.”

“Having”—“prepared the public mind, the assembly made a bold attack on the Church. They discovered, by the light of philosophy, that France contained too many churches, and, of course, too many pastors. Great part of them were therefore to be suppressed; and to make the innovation go down with the people, all tithes were to be abolished. The measure succeeded; but what did the people gain by the abolition of the tithes?—not a farthing; for a tax of twenty per cent. was immediately laid on the lands in consequence of it. The cheat was not perceived till it was too late.”

“But, the abolition of the tithes, the only motive of which was to debase the Clergy in the opinions of the people, was but a trifle to what was to follow.”

Then, with respect to the seizure of the landed property of the French Church; which was, beyond comparison, more extensive than that of our own:—“To obtain the sanction of the people to this act, they were told, that the wealth of the Church would not only pay off the national debt, but render taxes in future unnecessary. No deception was ever so barefaced as this; but even this was not wanted; for the people themselves had already begun to taste the sweets of plunder. Avarice tempted the trading part of the nation to approve of the measure. At the time of passing the decree they were seen among the first to applaud it. They saw an easy means of obtaining those fine rich estates, the possession of which they had, perhaps, long coveted. In vain were they told, that the purchaser would partake in the infamy of the robbery; that, if the title of the communities could not render property secure, that same property could never be secure under any title the plunderers could give. In vain were they told, that in sanctioning the seizure of the wealth of others, they were sanctioning the seizure of their own, whenever that all-devouring monster, the sovereign people, should call on them for it. In vain were they told all this: they purchased: they saw with pleasure the plundered Clergy driven from their dwellings; but scarcely had they taken possession of their ill-gotten wealth, when not only that, but the remains of their other property were wrenched from them. Since that we have seen decree upon decree launched forth against the rich: their account books have been submitted to public examination: they have been obliged to give drafts for the funds which they possessed even in foreign countries: all their letters have been intercepted and read. How many hundreds of them have we seen led to the scaffold, merely because they were proprietors of what their sovereign stood in need of! These were acts of unexampled tyranny; but, as they respected the persons who applauded the seizure of the estates of the Church, they were perfectly just. Several of these avaricious purchasers have been murdered within the walls of those buildings, whence they had assisted to drive the lawful proprietors: this was just: it was the measure they had meted to others. They shared the fate of the injured Clergy, without sharing the pity which that fate excited. When dragged forth to slaughter in their turn, they were left without even the right of complaining: the last stab of the assassin was accompanied with the reflection, that it was just.”

“I have dwelt the longer on this subject, as it is, perhaps, the most striking and most awful example of the consequences of a violation of property, that the world ever saw. Let it serve to warn all those who wish to raise their fortunes on the ruin of others, that sooner or later, their own turn must come. From this act of the Constituent Assembly we may date the violation, in France, of every right that men ought to hold dear. Hence the seizure of all gold and silver as the property of the nation: hence the law preventing the son to claim the property of his father: hence the abominable tyranny of requisitions; and hence thousands and thousands of the murders, that have disgraced unhappy France.”

These extracts are from pages 169, and 180, of a little book printed at Philadelphia, and reprinted in London about the year 1797: it is entitled, “The Bloody Buoy, thrown out as a Warning to the Political Pilots of America; or, a Faithful Relation of a Multitude of Acts of Horrid Barbarity, such as the Eye never witnessed, the Tongue never expressed, or the Imagination conceived, until the commencement of the French Revolution. To which is added an Instructive Essay, tracing these dreadful Effects to their real Causes.”

My Countrymen! the primary sources of all, were begin page 65 | ↑ back to top INFIDELITY; and those principles of rebellion and plunder, its legitimate offspring, which are now so industriously disseminated among ourselves: and if it be reasonable to anticipate like effects from like causes, we should be holding ourselves in solemn preparation for the worst: yet with no dreary misgiving, that the Providence which has so long signally blessed and protected this island, will forsake us in extremity: but with an ardent faith and confidence that He who has now withdrawn Himself for a while, and from His high and invisible watch tower in the heavens, is beholding the fury of His enemies, and the lukewarmness of his servants; will suddenly descend among us, and deliver us gloriously, at that moment when we shall lay the ark of our liberties on the altar of the sanctuary; and, banded together in one impregnable phalanx of holy patriotism—SWEAR TO DEFEND THEM IN HIS NAME!

Is this the rant of a fanatic?—NO. It is the zealous but sober voice of one who dares to speak what millions think: millions, who seem stunned and panic-stricken, by the yelling of a crew of savages, and a thoughtless rabble who follow them. It is the voice of one who would deem it happiness and glory indeed, to die for his country, in some great struggle against some great enemy: but who shudders to take his death at the talons of a club of runnagates whom his fathers would have hissed into the sea! It is the voice of one, who, among other histories, has perused the awful annals of the great French revolution, and has not nodded over the book: wherein rivers of blood, and plains of desolation; conflag[r]ation, assassination, violation, treachery, sacrilege, blasphemy, and every variety of wretchedness, and every enormity of abomination, are as familiar as household words.

And it is to this, Kentish Yeomen, that our heartless adversaries are reducing us: it is thus they began in France: and the most ready dupes of the Parisian radicals became the earliest victims of their fury, the moment they hesitated to plunge with them into gulfs of blood.

We charge the Radicals of England; and they will, perhaps, glory in the charge; with having eulogized that revolution through all its stages: with having palliated its atrocities, that they might promulgate its principles. Nor have they, from that day to this, left a stone unturned to accomplish an imitation of it among ourselves. Indeed we cannot refuse to admire the industry and ingenuity of these spiders; though we desire to tear their web: nay we could find in our heart, to pity the unfortunate fowler, who, after completing all his trains and contrivances; and standing ready in mute expectation with his hand half extended toward the prey; should suddenly behold all his nets, and gins, and springes broken in pieces. There will, indeed, be much sympathy, and much surprise, should we venture to transfer these doctors of absurdity, and “architects of ruin” from the University of Europe to the Academy of Laputa: should our frigid obtuseness be unable to conceive the sublimity of their vast plans for the emancipation of the species; after all the breath which the illuminati of more genial climates have spent upon us:—after all their performances on the Continent of Europe, to demonstrate it:—should we still be found unable precisely to apprehend, how the subversion of all government will tend to the security of peace, liberty, and property; and how exceedingly both learning and virtue, and above all religion and piety would be promoted, by the plunder and extirpation of Christian establishments!

The sentimental Ceruti said, with his last breath, “The only regret I have in leaving the world, is, that I leave a religion on earth.” His words were applauded by the Assembly, the Radical Assembly of France. And it is, no doubt, with many of our own tender hearted liberals, a melancholy reflection; that their most venerable and hoary sages of revolution may, even now, perhaps, not survive every civil and religious institution:—that they may “go to their own place,” before they have amassed a full legacy of curses for their posterity. However, no exertions have been wanting on their part: their efforts have been alike patient, orderly, united, and energetic. Their army is at last drawn out; and is about to make the grand charge. It has many raw recruits: but many disciplined veterans, and able marshals. Their watchwords are Liberty, and Reform: noble words indeed, but most foully abused. Let us execrate their principles; but imitate, for once, their union and energy. If we are divided, and disorganized; and above all, if we are panic-stricken, every thing is lost. No superiority of numbers will avail us, if we are separated, or wavering, or unprepared. In 1780 eight hundred thousand Londoners looked on in consternation, while a handful of pickpockets ravaged their property for three days! An eye witness of the Bristol outrages declared, that at the beginning, forty persons might have dispersed the rioters easily. On the 9th of November 1830, the leaders of the Radicals not being prepared to show themselves; and being disconcerted by a premature discovery of their plot; their mobs being consequently not so well organized as the police; the latter saved the metropolis from destruction. It was, I think, Marat, one of the Radical Reformers of France, who boasted that with three hundred ruffians hired at a Louis d’or per day, he could govern all France: and why? because all France was dismembered and panic-stricken.

Let us remember the fable of the lion and the bulls.

It is true we vastly, and beyond comparison outnumber the enemy: but then we are men of peace; and they are beasts of prey. We are strongest by day: they ravine in the night; for their optics are adapted to darkness. And it is now a very dark night for Europe. The radicals are elated; for it is a dark and foggy night; when begin page 66 | ↑ back to top thieves are always on the alert. They are housebreakers: we are quiet householders, who have drawn the curtains, and retired to rest!

Permit me to suggest to you, Electors of West Kent, that this is no time to multiply party distinctions, or to remember old grudges. We should travel in Caravan; prepared against a horde of thieves far more cruel than wandering Arabs. These highwaymen will rifle us if they catch us singly; but take to their heels over hedge and ditch, should they once meet us walking together on the King’s Highway.

Let the good old Whigs, the Tories high and low, and the men of no party, for once come together, and twist a threefold cord which may not easily be broken.

It was thus Britain was saved in 1792, from a revolution which our illuminati were then on the very point of effecting. She was saved by nothing less than an inspiration from Heaven: by nothing else than a most sudden, universal revulsion of patriotism; and a simultaneous consociation, from one end of the kingdom to the other. And this revolution our abandoned Liberals had striven to bring about, while the blood of France was yet hot and reeking; and with the stench of that great butchery under their nostrils! In the extension of their philanthropy, which, indeed, they truly allege to be trammelled with no vulgar demarkations of patriotic geography, they were instituting a flesh market for the cannibals of Europe; and preparing to slay their brethren for the shambles. France was too narrow for them: and they were about to enlarge that slaughter-house of Europe by throwing into it the habitations of their fathers.

The French had been smitten with giddiness from God; and distracted with delirious theories, more multitudinous than the tongues of Babel: but it was not while they were aspiring to raise a pinnacle to the skies; but were laying, in the very depths of Hell, the foundations of a charnel-house for Christendom.

But they meted out upon themselves the “line of confusion and the stones of emptiness.” After laying waste one of the richest countries in the world, to obtain liberty and equality; they fell at once into the most abject military bondage, under a remorseless tyrant; who, wonderful to say, has ever been the pagod of our own most furious republicans and levellers: at whose spoliation of the liberties of Europe they exulted: at whose signal defeat and overthrow, by the blessing of God on the valour of their countrymen, they have scarcely ceased their wailings to this day.

In words, they are peace-makers and philanthropists: in deeds, they are incendiaries and assassins. They extenuated Buonaparte’s most unprovoked a[g]gressions and invasions; and had he invaded their own country, would have hailed him with acclamations! But, when the standard of Spanish independence was lifted up; no sooner did Wellington and British valour drive him from the Peninsula, and unbind the nations; than truly, on a sudden, no cloistered maiden was to be found so sensitive, nay, so pious as the Radical! Yes, he who had beheld with sullen indifference the excesses of Robespierre, and with savage transport the exploits of Napoleon; would now, forsooth, doubt the very lawfulness of defensive warfare! He would question whether any true disciple of the Prince of Peace could take up arms! He would faint at the clash of a sword or the beating of a drum!

Gratitude the Radicals do not know. Their insolence ever increases with indulgence. Till they get the power into their hands, they whimper like school-boys; nay they can sob, and lisp, and languish like an infant:—the moment they are elevated, they dash in pieces the dupe who lifted them up. They are a generation of crocodiles, who mimic the wailings of distress, and devour those who come to relieve it.

They can put on the most saintly garb of Apostolic simplicity; and associate with the disciples that they may betray the Master. They are, at present, filled with apprehension, lest Christiantiy should suffer through an over-fed priesthood; and are most politely assiduous to relieve them of their superfluities: nay, so earnest are they found in this pious work; that even freehold estates, secured by the most indubitable titles to the Church, and legacies entailed upon it with the most awful sanctions, would be alienated at their touch: and signatures, and seals, and stamps, and rolls of parchment, would become dissolved in a moment, in the furnace of their Evangelical charity! Did our fathers pour forth their treasures at the feet of the Redeemer; and, in the most solemn manner, endow the Church with them for ever?—Hark!—these children of Judas Iscariot are inquiring, “Why is not all this sold, and the money given to the poor?[”]—But this they say, not because they care for the poor; but because they are thieves, and desire to clutch the bag, and to make off with its contents!” [sic]

The Radicals have long clamoured for Parliamentary Reform, and a full representation, as the national panacea. This has been granted them, even to the extent of their own desires: and are they satisfied? Are they about to treat this reformed Parliament, this darling of their hopes, as nursing mothers?—or have they, while it is yet in the womb, prepared their political unions to hector over, and bully it?

They now declare that this is but a first step: it is tolerated, however, because they imagine that they behold in it the dawn and twilight of a republic.

By this faction the Queen has already been most publicly menaced with the scaffold, in terms aggravated by personal insult: and our Sovereign, whose venerable parent’s memory is, at present, a favourite butt of their savage vituperation: our beloved Sovereign, whose reign has been hitherto one series of concession; will fall the begin page 67 | ↑ back to top earliest victim to their baseness and perfidy; unless it should please the Almighty to dash their projects, and to “turn the counsel of Ahitophel into foolishness.”

The English Radical, and the Gallic Jacobin “are brethren; instruments of cruelty are in their habitations. O my soul, come not thou into their secret; unto their assembly, mine honour, be not thou united: for in their anger they slew a man, and in their self-will they digged down a wall. Cursed be their anger, for it was fierce; and their wrath, for it was cruel.” They are the abortions and monsters of the moral universe; uncouth, perverse, and opposite to nature. They will grovel in the dust before a tyrant: but with a gentle and parental Sovereign “their neck is as an iron sinew; and their brow brass.” They will cringe under the rod; and bite the hand that caresses them.

And will you, my countrymen, suffer this deplorable faction to pour out, not their representatives, but their delegates over the counties: to send forth their foxes, two by two, into your harvests, tied together by revolutionary pledges; and dragging between them the firebrands of destruction? Samson sent fire-b[r]ands to the Philistine fields. But we, if we make Constituents of these foxes of free trade and liberalism; shall be directing the matches of a starving peasantry to our own garners; and politically, shall light up such a fire in our country, as nothing will extinguish but the waters of desolation.

Samson, in death as in life heroic, brought down upon his head the vault of Dagon; and perished with his foes. But we are shattering the citadel of our own strength; the tabernacle of our constitution, the temple of our liberties, and the sanctuary of our God. We are tugging at those two main pillars; our loyalty and our piety; and shall be ground to powder, in the crash and perdition of our country.

So fond are mortal men,

Fallen into wrath divine,

As their own ruin on themselves t’ invite;

Insensate left or to sense reprobate;

And with blindness internal struck.”

Milton.

Brother Electors; we have been requested to return to Parliament two Gentlemen, who have, unhappily, ranked themselves under the standard of the, so called, Radical Reformers. Personal remark is remote from my intention: but I would remind you that the Radicals have ever been found adverse to the agricultural interest: that whatever they may pretend; they will, if possible, sweep away your protecting duties.

Farmers! They were the wretched leaders of this wretched faction, who, during the late dreadful fires, strenuously encouraged the incendiaries! Some of the most abandoned of them published cheap tracts for distribution among the poor, stimulating them to fire their master’s property. But now, if there be a Radical Parliament; the starvation produced by free trade, and the consequent reckless desperation of the peasantry; will supersede the necessity of all other stimulants. If, then, you patronise Radicalism, in any shape, you will have yourselves to thank for the consequences.

Already, the fires have begun. Do you wish them to blaze once more over the kingdom? If you do; send Radicals into Parliament; make Radicals of the poor; and as those principles effectually relieve all classes from every religious and moral restraint; neither property nor life will be for a moment secure. Conflagration has already ravaged your harvests; and assassination and massacre are in its train.

Landholders, who have estates to be confiscated, or laid in ashes: Farmers, who have free trade, and annihilation impending over you: Manufacturers, who must be beggared in the bankruptcy of your country: Fund-holders, who desire not the wet sponge: Britons, who have liberty to lose: Christians, who have a religion to be blasphemed: now is the time for your last struggle! The ensuing Election is not a question of party politics; much less, a paltry squabble of family interests: but Existence, or Annihilation, to good old England!

Let us then rally once more: Whigs, Tories, Moderates; and especially every Christian man in West Kent;—it may be for the last time;—round the noble standard of Old Kentish Loyalty; and defend it to the last. If we triumph; our children will say of us;—“These were the sacred heroes, who, amid the convulsion of the world, serenely held fast, and transmitted to us the birthright of our liberties: nay, all our glory, in the inheritance of the British Name.” If we perish in the contest; let it not be, O Spirit of Albion, as recreants and dastards: but with Thy standard clenched in our grasp; or folded about our hearts!

God prosper the good old cause: it is His Own. Is it the cause of old England: of our beloved Monarch: of our nobles: most truly of all our middle classes; and preeminently of the poor; who, in the destruction of commerce and agriculture; of order and property, get nothing of the spoil; but suffer every extremity of wretchedness and famine.

The other cause is that of the Devil and his Angels; masked under a pretended indignation at State tyranny, and Church corruption: witness, again, the great French Revolution: wherein the King, after making every just concession, and much more was savagely murdered: the nobles were massacred and banished: the Clergy butchered by companies, or assassinated at their church doors. A strumpet was dressed up, and publicly adored in the Cathedral of Paris, as the Goddess of Reason: our Saviour was denounced as an arch imposter, and the profession of his religion was prohibited!

The whole Radical and Atheistical party of England is now marshalled against the constitutional and religious; begin page 68 | ↑ back to top and Europe is looking on in solemn expectation[.]

The result of the ensuing Election will turn the balance. One additional Conservative Member may save this great nation:—the vote of any one individual may secure that Member’s election. Every friend to our cause, however humble, should energize as if all depended on himself.

Unanimous co-operation and individual energy may do all things.

Electors; he who has thus taken the liberty to address you, however inadequate to the task; claims, at last, the merit of disinterestedness. Sir William Geary is personally unknown to him: nor will he obtain any sort of benefit by that Gentleman’s return to Parliament. He has addressed you, without the instigation of a second person: without the knowledge of Sir William, or any of his Committees. The writer receives not one farthing of the great or small tithe: he has no connection with, or dependence on the Clergy: he is neither a prophet, nor the son of a prophet. Alas! it is no longer a little cloud of the bigness of a man’s hand, which hovers in our political horizon, but a blackness of [word illegible] which it requires no prophetic direction to perceive. He is not accustomed to push himself forward: he loves not to hear himself talk; but would rather have listened while another spoke. He has not obtruded into the front ranks of the loyal army: but would be overwhelmed by the sense of such presumption. He has waited long in the rear and outposts, hoping that some stronger arm might be lifted up against the big and boastful Philistine of Jacobinism, who has hurled defiance alike at the institutions of men and the armies of God. And he has no heartier desire than that while he is picking up these few pebbles from the brook, and cutting out this rustic sling, he may be superseded and borne away by one sudden acclamation of re-kindled patriotism from Guernsey to the Hebrides: that Britain may never become intellectually a province of France: that her wolves of revolution may hear once more the British lion roaring from the cliffs of Kent, and be discomfitted: that we may never like the Trojans; whom old historians repute our ancestors; be undone by the presents of an enemy: but that the liberty and equality which our treacherous neighbours have offered us, as winged steeds to be yoked into the car of human improvement; may be timely suspected to be full of armed men: and, finally: that all our countrymen who have been deceived and over-persuaded by the internal troublers of our peace, may have the true nobility of mind readily and frankly to confess their mistake: and, instead of setting by the ears every class and order of society; may strive as heartily to promote that universal good will, and blessed brotherly union, which are the only root and basis of our prosperity and strength: which are able to lift us up, once more, in the scale of nations; and to constitute Britannia, as she was ever wont to be, the arbitress of the destinies, and the guardian of the liberties of Europe.

FINIS.